This article is the third of five stories about crimes against journalists in Colombia, especially Indigenous reporters in Cauca province, supported by the JFJ Investigative Grant Programme. The article was originally published on Global Voices.

Editor’s note: this profile is part of wider coverage of threats against Indigenous reporters in Cauca (Colombia). The first story covers impunity regarding crimes against reporters, and the second, the context of indigenous and their fight to report on community land struggles.

It was an ordinary Sunday, with no hint of trouble. María Efigenia Vásquez Astudillo and her partner John Miller, both Indigenous reporters from the south of Colombia, took their camera and went to the Kokonuko indigenous reserve.

Miller’s job was to record the protest of the Kokonuko Indigenous community and their subsequent encounter with the police anti-riot unit, Esmad. The events took place at the Kokonuko reserve, in Puracé, a small town a couple of hours from the large city of Popayán.

Miller told Global Voices that he and Efigenia Vásquez had been called by people from their neighborhood to document possible confrontations with the police. The Kokonuko community had gathered to protest a private tourism project, led by Diego Angulo, on what they consider the heart of their reserve (resguardo, in Spanish), which is under collective property according to Colombian law.

On the morning of October 8, 2017, the couple was near the entrance of Agua Tibia N.2, in the reserve, which is also the location of Angulo’s ecotourism, spa, and thermal baths company called Centro de Turismo y Salud Termales Agua Tibia.

Miller said he was recording with their equipment, as Vásquez taught him—without distractions and focused on the possible confrontation between police and indigenous people. At around 3 p.m., Vásquez suggested they go back home to take care of her three children.

As they walked down the mountain, she suddenly looked at him, saying, “I am going this way.” She went to the other side of the mountain. Miller continued recording.

He captured an Esmad member shooting, but could not see the target, and then he heard community members screaming for help. Immediately, he put down this camera and looked for where the cries were coming from.

He was shocked when he saw Vásquez’s body lying on the ground and went towards her with other community members. On the road below, the Esmad was still confronting people and making it impossible for the ambulance to pass.

A driver, who was passing by on the road, transported Vásquez to the ambulance so they could take her to the closest hospital. However, the small town did not have enough equipment, so they took her to Popayan’s Cauca at Saint Joseph Hospital.

During this time, Vásquez said, “Please don’t let me die,” and “Don’t tell my parents what happened.” A few hours later, a nurse told Miller they could not save her. He was devastated—his loved one and co-worker died from bullet wounds. The next day, the Legal Medicine Institute confirmed her death by a gunshot.

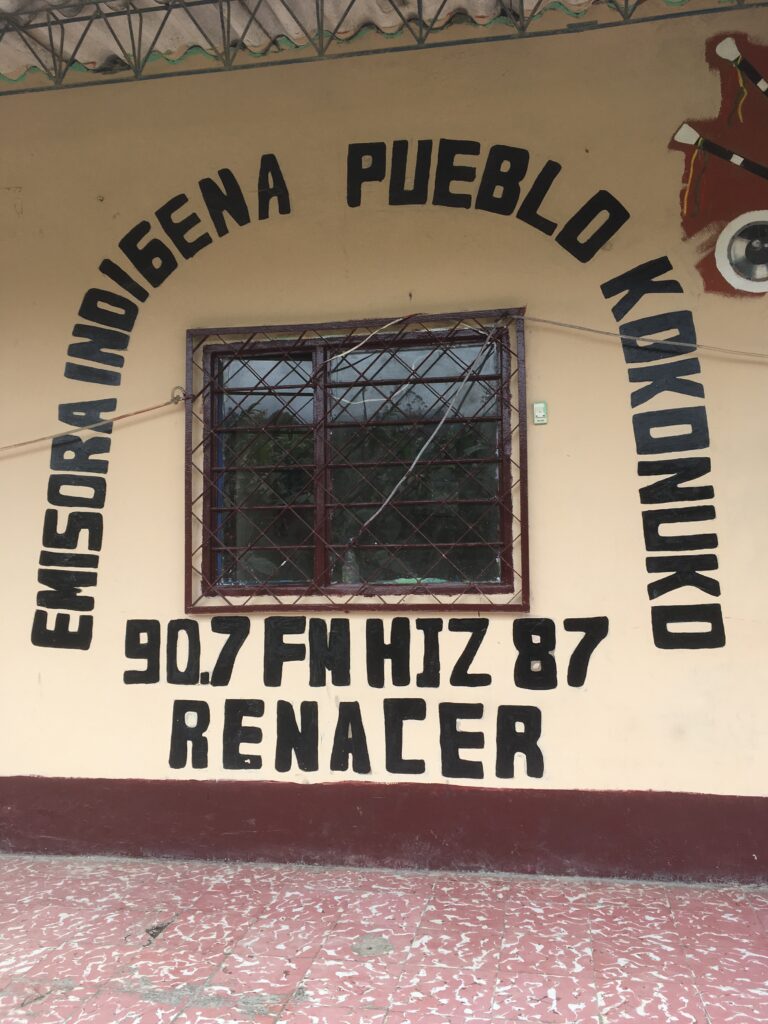

Vásquez Astudillo, Indigenous Radio Renacer Kokonuko reporter, former Indigenous guard, and a mother of three, died while reporting on her community’s struggle to recover their land. Although it was four years ago, her death inspires the community to keep their fight for their reserve and collective property.

Fighting for ancestral land

Land recovery is fundamental to the Kokonuko because their identity is rooted in Mother Earth.

Sulma Yace, an ancestral Kokonuko authority, emphasized their relationship to Mother Earth. She also said that they are more committed to defending Agua Tibia N. 2 since Vásquez was killed there, as she was reporting on their community struggle. In 2021, Indigenous communities still protest the presence of Diego Angulo’s thermal resort on their reserve.

For his part, Jhoe Sauca, the legal representative of the Kokonuko at the Indigenous Regional Council of Cauca (Cric, for its acronym in Spanish) told Global Voices why it is so important to recover Agua Tibia N.2: “to extend their reserve; to practice traditional rituals and to claim the right to the territory in the name of Efigenia.”

As Vásquez was killed doing her work, the Foundation for Press Freedom (FLIP, for its acronym in Spanish) told Global Voices that Colombia’s Attorney General should follow procedure and take into account Esmad’s aggressions against journalists.

By email, the Attorney General’s Office replied to Global Voices’ request, informing us that there is a disciplinary process open against the police agent for the following conduct: “extra limitation of rights and innominate functions.”

Although justice seems far for Vásquez, her legacy lives on. Her three children remember her as a devoted mother, passionate about her work at the radio station, and committed to her Indigenous community.

Her mother, Ilda Astudillo, was happy because her daughter became what she wanted: a broadcaster. Her father, Luis Vásquez, continues to be inspired by her dreams to study journalism and law, which she couldn’t accomplish.

John Miller, her partner in work and life, said that despite this fatal event and the risks that Indigenous communicators face in Cauca, he will continue reporting from Agua Tibia N.2. “As María Efigenia Astudillo said: ‘How can I run, I must be strong, have personality, and I cannot allow myself to be defeated,” he said, reminiscing.

“We must act following our thinking,” John added.