AUTHOR OF THE REPORT: SCHOOL OF PEACEMAKING AND MEDIA TECHNOLOGY IN CENTRAL ASIA

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Kyrgyzstan, 130 cases of attacks/threats against professional and civilian media workers, and editorial offices of traditional and online publications, were identified and analysed in the course of the research for 2022. Data for the research, carried out over the course of 2022, was collected using open source content in three languages: Kyrgyz, Russian and English. Reports of incidents sent directly to the Foundation by media workers were also analysed. A list of the main sources is provided in Annex 1.

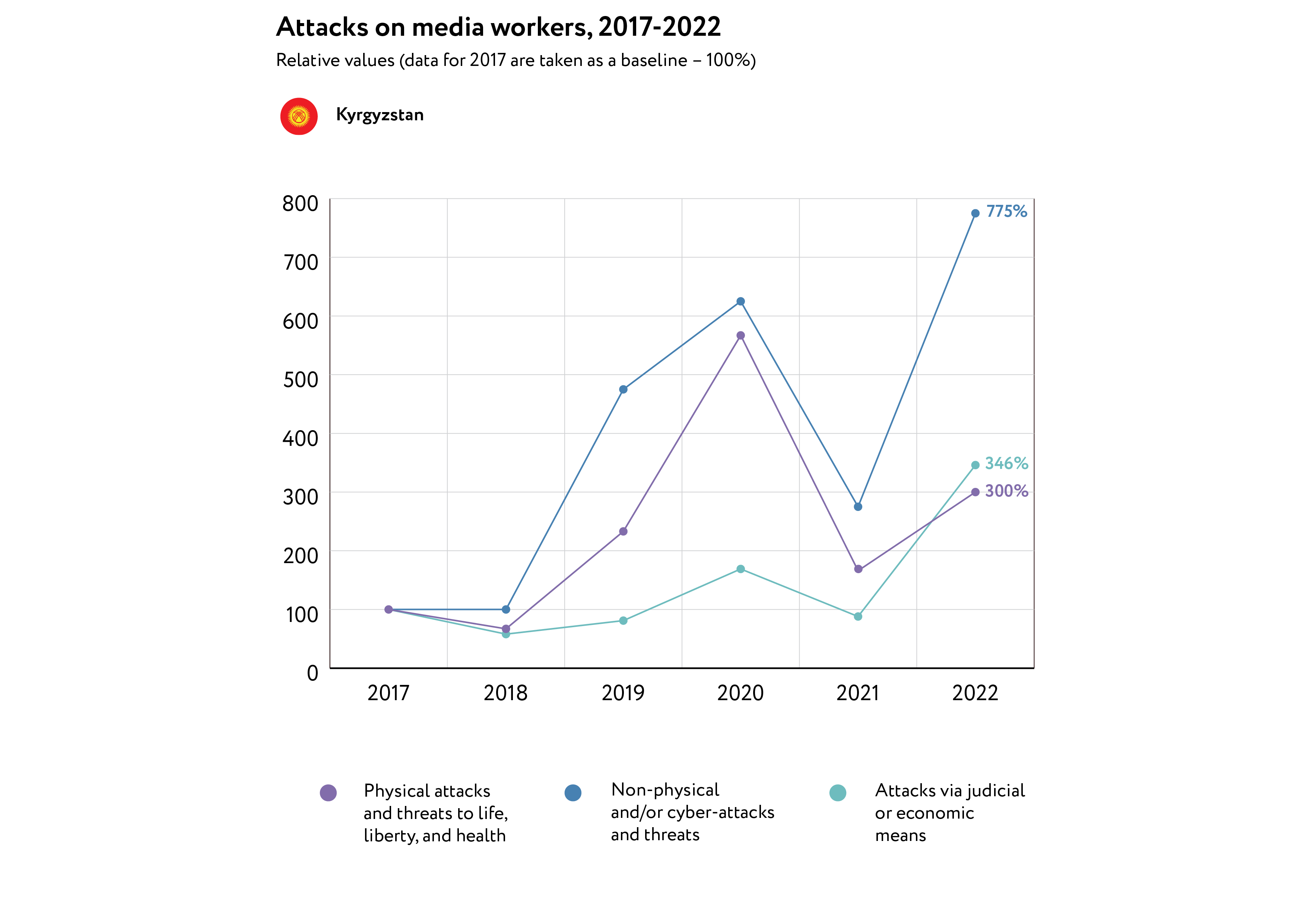

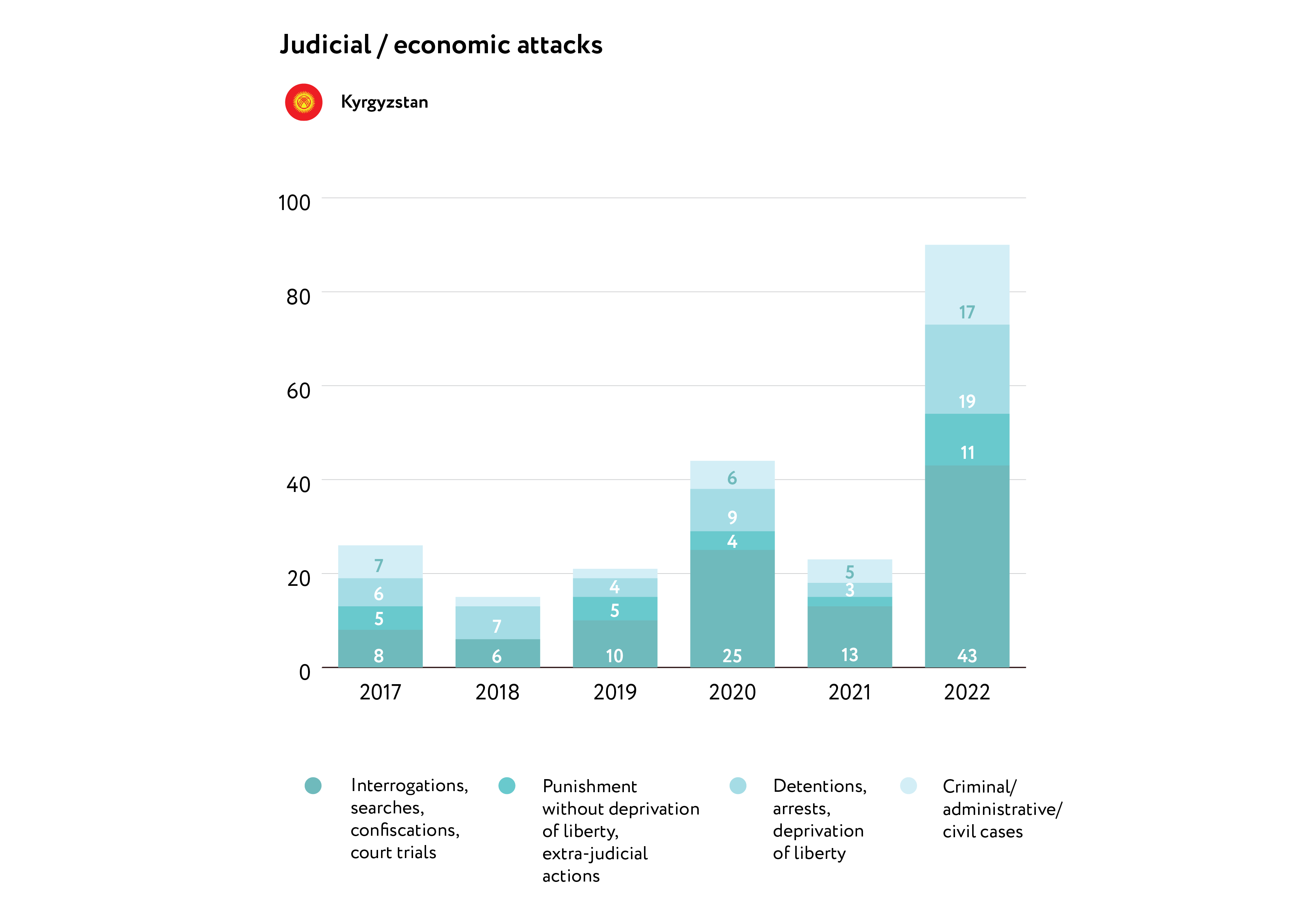

- In 2022, authorities carried out unprecedented numbers of attacks on freedom of speech, partly in response to journalists’ ongoing investigations into corruption in Kyrgyzstan. Since 2021, the number of incidents has tripled.

- Attacks via judicial and/or economic means remain the main method of exerting pressure on media workers, accounting for 70% of the total number of incidents.

- There was a sharp increase in the number of journalists being arrested, interrogated, and tried in court as a result of their work.

- In addition to this, the number of cyber attacks against both media outlets and journalists almost tripled.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN KYRGYZSTAN

According to the 2022 annual rankings published by Reporters Without Borders, Kyrgyzstan ranked 72nd out of 180 countries, improving upon its 2021 ranking by 7 places. According to Reporters Without Borders, Kyrgyzstan “enjoys relative freedom of expression and of the press” and that, despite state control over traditional media, there is “a degree of pluralism” in the media. However, there were numerous instances of restrictions on freedom of speech and threats against both domestic and international media recorded throughout the year.

In Freedom House’s 2022 Freedom in the World global ranking, Kyrgyzstan remained in the category of “not free” countries. Kyrgyzstan’s score dropped by 1 point compared to the previous year – to 27 out of 100.

The intensified persecution of journalists was brought on in part by investigations into the conflict on the Kyrgyz-Tajik border in January and September, when local journalists often presented dissenting opinions. In February, criminal cases were brought against the Next TV channel and the independent editorial office Kaktus.media. The Bishkek prosecutor’s office summoned several of the publications’ editors for interrogation after they reposted links from a Tajik media outlet.

The Prosecutor General’s Office stated that the material contained “inaccurate information” and initiated criminal proceedings.

During this time, a group objecting to Kaktus.media journalists providing information about the conflict on the Kyrgyz-Tajik border to the Tajik site Asia Plus staged a protest outside the editorial office of Kaktus.media, demanding that the publication be closed down.

A few days later, a group of pro-government activists and bloggers held a press conference demanding the introduction of “foreign agent” labels to certain publications, in particular Kaktus.media, Azattyk and Kloop. A similar demand was raised in an open letter, which was allegedly signed by 70 public figures. The letter stated that all three publications were “foreign” and that their activities contravened the national interests of Kyrgyzstan.

In October, authorities suspended the Azattyk Media website for two months following the publication of a video titled “Heavy Fighting on the Border of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.” This material allegedly “contradicted the national interests of the Kyrgyz Republic (inaccurate information about the events of September 14-17, 2022),” contained hate speech, as well as incited discrimination and division among citizens, while covering events in the Batken border region. However, lawyers, human rights activists and media experts noted a number of legal violations during the blocking of the website. There were no grounds for this legal action, nor was there a recognised charge to warrant the site being blocked.

At the same time, authorities continued to crack down on media outlets and the dissemination of information. The Kyrgyz government nationalised the Public Television and Radio Corporation, and abolished its Supervisory Board. As such, the general director was appointed directly by the President.

In 2022, the authorities gave the Ministry of Digital Development the ability to rapidly block online resources without a court decision.

According to the Unified State Register of Statistical Units, there were more than 1,800 mass media entities in the country at the start of 2022, including 177 independent television/radio companies, 77 accredited online publications and 60 newspapers.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

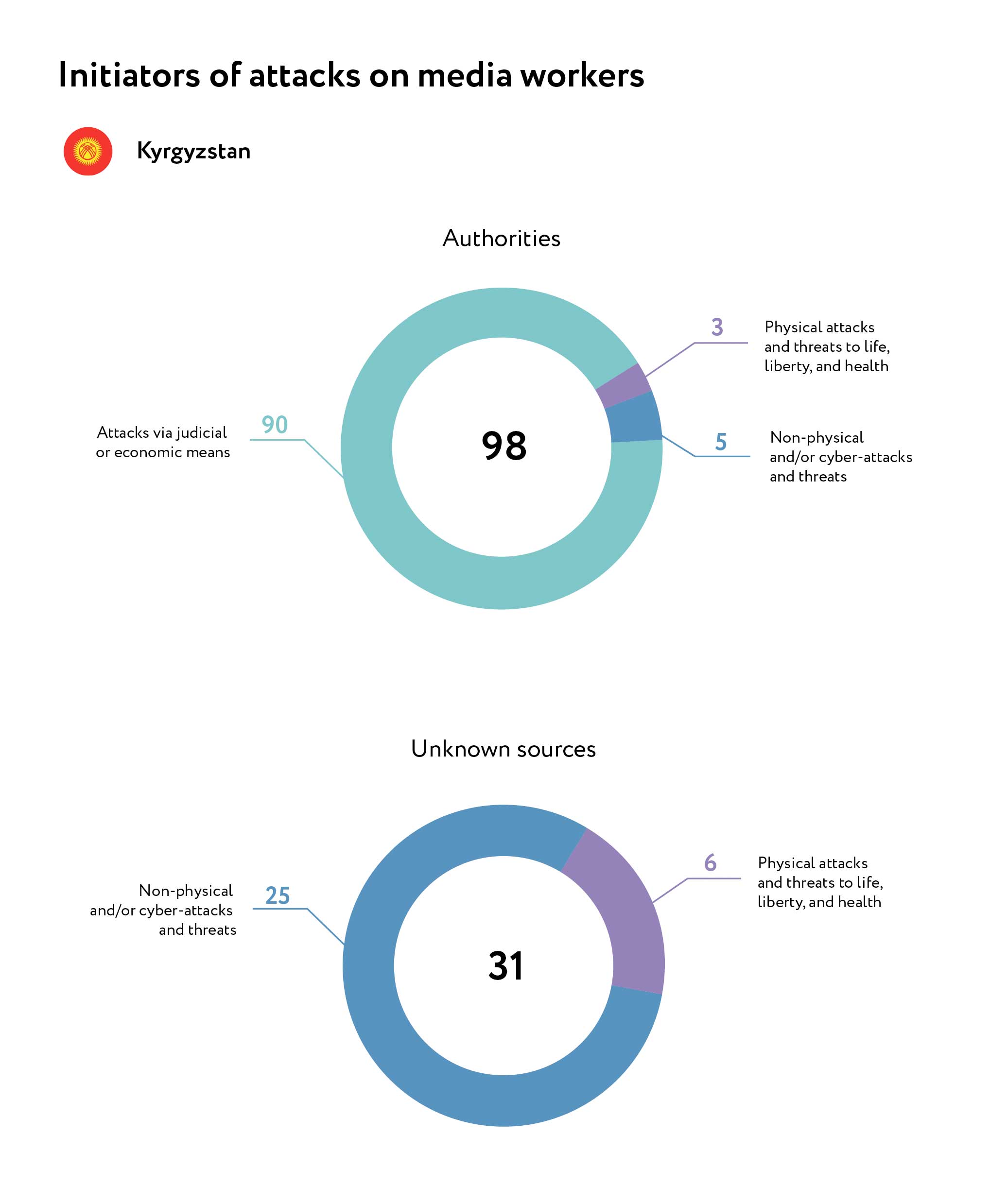

In 2022, 130 attacks or threats of attacks were recorded against journalists, bloggers, media workers and editorial offices of traditional and online publications. Since 2021, the number of attacks against media workers has tripled. These attacks were mainly related to journalists covering conflicts. In 75% of cases, attacks on media workers were committed by government officials.

In 2022, experts highlighted worsening conditions regarding freedom of speech, access to information, and an increased level of censorship. In October, Kyrgyzstan’s parliament began considering new legislation that would require all media outlets to re-apply for registration and impose restrictions on any media outlets receiving foreign funding. Independent lawyers claimed that the adoption of this legislation could lead to the closure of numerous media outlets, and prevent journalists from publishing their investigations. The bill‘s restrictions can be applied to websites and social media accounts, making any internet user potentially liable.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

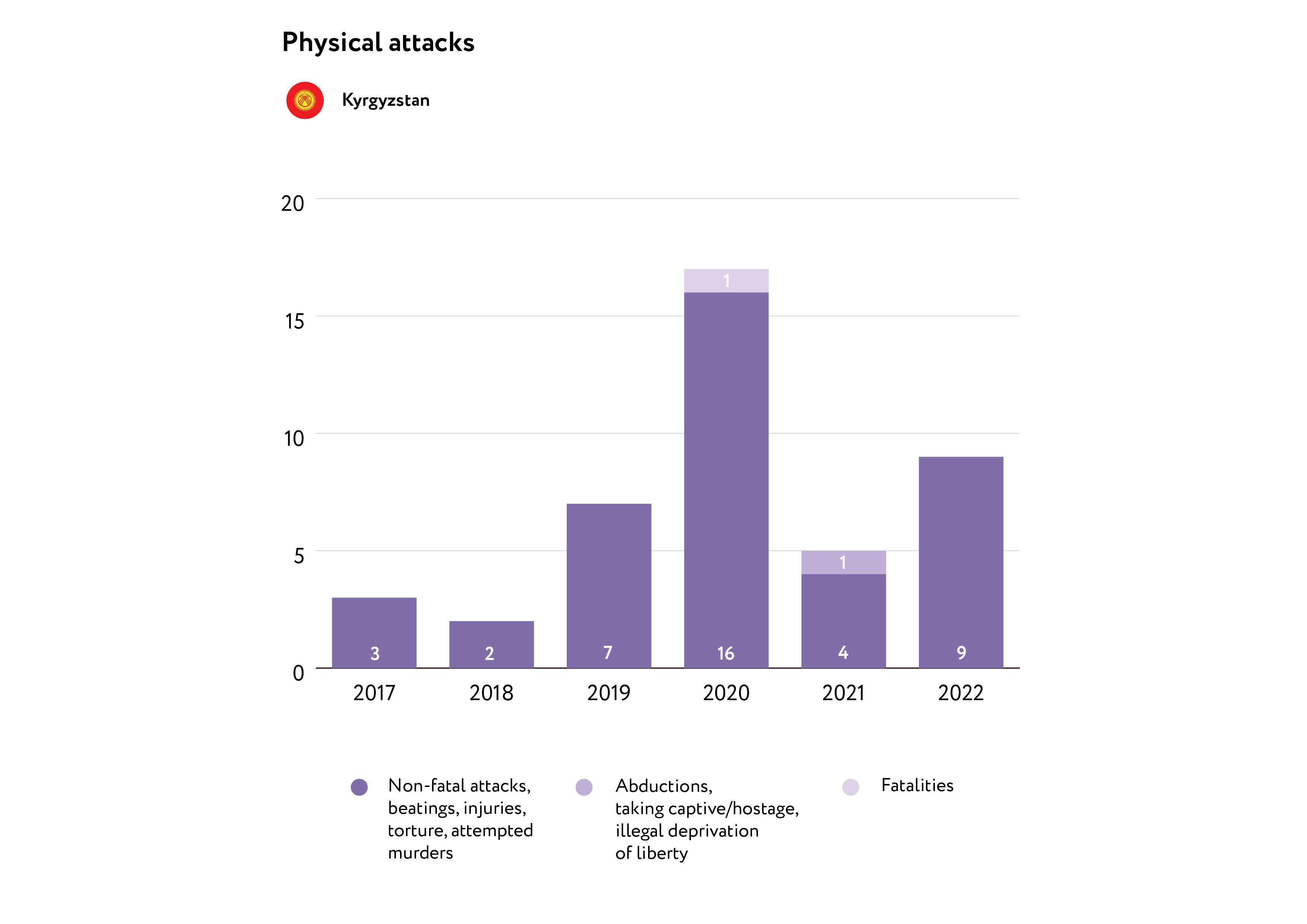

All physical attacks recorded in 2022 were non-fatal and were mostly committed while journalists were performing their professional duties. Compared with the previous year, the number of physical attacks doubled. These attacks were committed by unknown individuals in all but three cases:

- On February 5, blogger Batmakan Zholbolduyeva was attacked by the head of the Akimiat (the local district administration) during a broadcast in Isfana (southwestern Kyrgyzstan). She was reporting on an off-site meeting between two parliamentary factions whose deputies visited the region following the conflict on the Kyrgyz-Tajik border. While Zholbolduyeva was broadcasting, Alikhan Uraimov insisted that she leave the building. He claimed that the blogger “did not represent the official media” and tried to force her out of the meeting room. He stole her phone, struck her, and pulled her hair.

- On February 8, during a visit by President Sadyr Japarov to the Osh market in Bishkek, Super.kg journalist Zhyldyz Dzhuskembayeva was subjected to intimidation by two police officers. Police grabbed her, forcefully removing her from the area where the President was talking with local merchants.

- On September 2, Yrys Zhekshenaliev, a 19-year-old blogger and admin of the Polituznik Facebook page, was forcibly removed from the Bishkek City Court. Zhekshenaliev claims his arms were injured during the incident.

Other recorded physical attacks included:

- On February 28, unidentified individuals attacked Yrysbay Mazhitov, a TV reporter for Nur.TV, in the office of the vice-mayor of Osh while he was waiting for an interview, knocking out several of his teeth. The journalist sought medical help and provided a written statement to the police.

- On April 1, the film crew for the “Ne sakhar” project was attacked in Moskovsky district, 43 km west of Bishkek. The attack took place at a slaughterhouse where the journalists were filming a report on the results of an investigation. During filming, approximately 20 people surrounded the journalists, and stole their camera and phones. The attackers also took the memory cards out of the journalists’ devices and equipment and deleted their material. The journalists had applied to the Department of Internal Affairs of the Chui region.

- On June 2, an unidentified individual attacked investigative journalist Bakyt Kulchumanov at the offices of the State Agency for Registration of Rights to Real Estate (GosRegister). The assailant struck the journalist in the jaw, tore his clothes, and broke his glasses. The journalist was investigating so-called “green books” (illegally sold documents for agricultural land on which construction is prohibited) at the time of the attack. After the attack, the journalist was told that his assailant was not affiliated with GosRegister.

- On September 17, Davron Nasibkhonov, a correspondent for the Uzbek edition of Voice of America, was stabbed several times in the back by an unknown individual, fell to the ground and lost consciousness. The attack took place near the Osh city hall, where the journalist was preparing a report on humanitarian assistance to victims of the armed conflict on the Kyrgyz-Tajik border. According to the journalist, the assailants thought that he was a Tajik spy.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

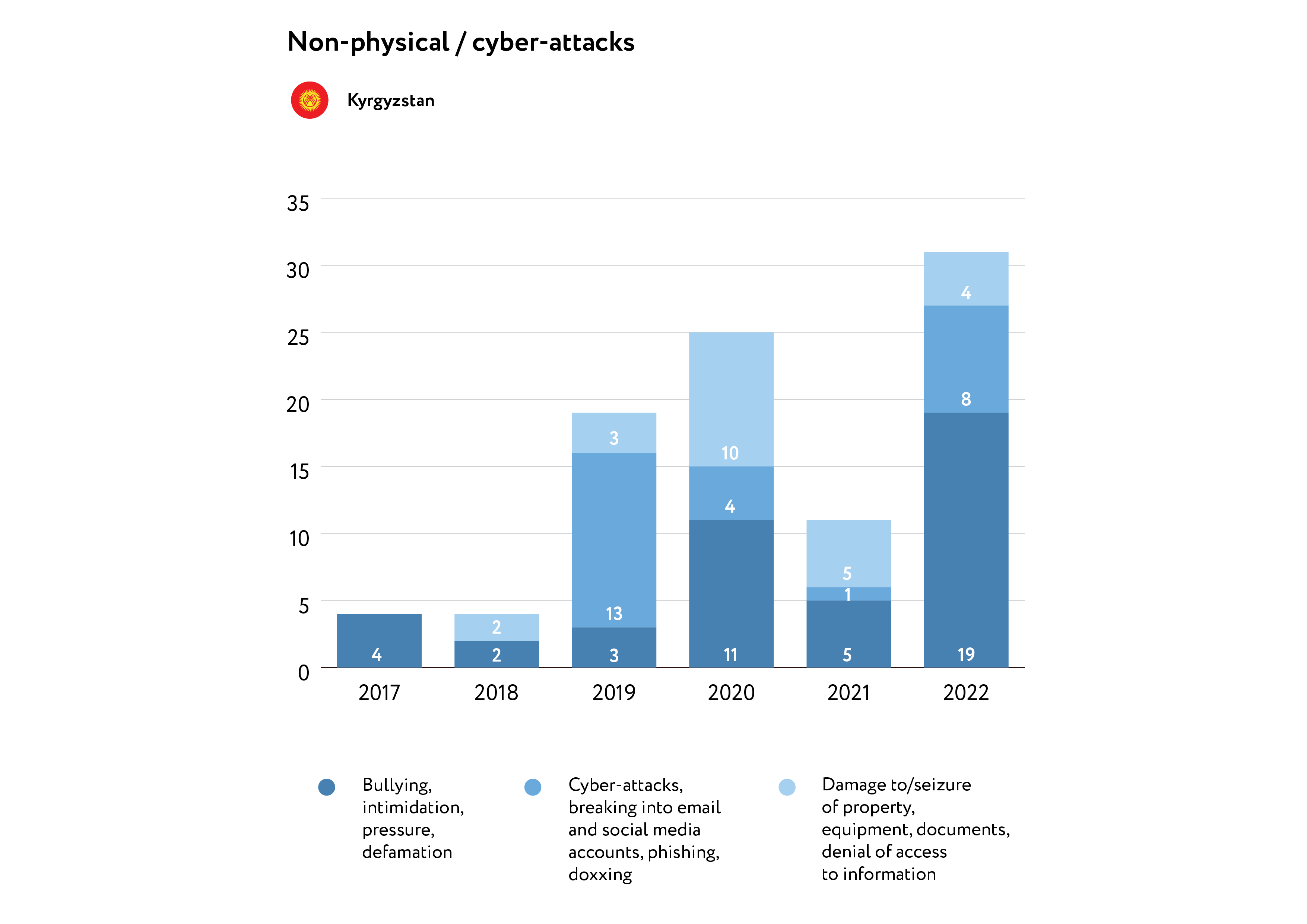

Bullying, intimidation, and defamation remain the most common forms of attack on media workers. Since 2021, the number of such incidents has quadrupled. In 2022, there were at least eight incidents of cyber attacks and the hacking of emails and social media accounts. Unidentified individuals were responsible for 80% of these attacks, while 16% were carried out by government officials.

Groups and individuals wishing to silence media outlets and journalists held violent demonstrations near the editorial offices of a number of media outlets over the course of 2022. In October, prior to authorities taking the decision to block the website of Radio Azattyk (the Kyrgyz branch of Radio Liberty), violent crowds rallied against the station, as well as Kloop and Kaktus.media. Unidentified individuals threatened journalists with violence, threatening to “douse them with gasoline and burn down their offices”.

In 2022, the main methods of exerting pressure on journalists were bullying, intimidation, and slander. Over the course of the year, 19 such incidents were recorded:

- On January 22, Temirov Live employees issued an appeal after journalist Bolot Temirov was arrested while investigating alleged corruption. Bolot Temirov was detained on the evening of January 22, 2 days after the publication of an investigation into the oil industry’s connection to Kamchybek Tashiev’s relatives (the head of the State Committee for National Security). According to journalist Aktilek Kaparov, in December 2021, a hidden camera was found in the bedroom of Bolot Temirov’s house. Later, Temirov Live employees began receiving threats and journalists were forced to give prior notice about their intentions to investigate specific topics.

- On January 28, following his arrest, Bolot Temirov faced insults and comments discrediting his work on social media. Anonymous people posted several videos on Facebook, in which the journalist was referred to as a “criminal” and “traitor” in an attempt to portray him as a foreign agent.

- On January 28, people gathered near the Kaktus.media offices to protest the publication’s coverage of events on the Kyrgyz-Tajik border. Protesters demanded that the publication apologise and be shut down for spreading “incorrect” information.

- On February 2, a Temirov Live employee was subject to sexual blackmail by members of the security services. The woman employee had met a man at a gym, with whom she began a relationship. While they were in a relationship, the media worker’s laptop was hacked, and the two were filmed having sexual intercourse. The explicit video was shared online. Later, law enforcement sources claimed that this man worked for the State Committee for National Security. Employees attempted to use the footage as leverage to find out details of Temirov’ Live’s upcoming investigations. They also demanded that the woman employee sign a cooperation agreement to spy on her employers.

- On February 24, unknown individuals threatened 24.kg reporter Yuri Kopytin on Telegram following the publication of an investigation into the use of counterfeit money. After the story was published, a Telegram user using the account @FalshSom sent a message to Kopytin that read: “They are already looking for you, watch your back, you don’t have long to live.” Kopytin posted an official appeal to the Ministry of Internal Affairs on Facebook, requesting that it identify and prosecute the anonymous person. The article about counterfeiters was published on February 23, 2022, after a reader contacted the 24.kg editors, claiming that people were anonymously selling counterfeit cash.

- On August 15, journalist Shokhrukh Saipov was threatened online, having complained about taxi drivers at the Osh airport and at the Dostuk border checkpoint. In an interview with the online edition of ACCA, he said: “Most of the threats I get are on social media. I get threatening direct messages, saying that I am inciting ethnic hatred, and that if I don’t like Kyrgyzstan, then I can go live in Uzbekistan. They asked why I am defending Uzbeks, and told me to watch my back. I pass most of these posts and comments on to the police. Sometimes I get threats via my friends. They ask for my contacts, my address, etc. They contact my family and try to find out more about what I’m working on,” the journalist said.

Cyber attacks, email hacking, phishing, and doxing were the second most common methods used to exert pressure on media workers.

- On February 1, unidentified individuals hacked the Instagram account of Kaktus.media. At approximately 17:50, the editorial office’s social media marketing team lost access to their account. This hacking attempt was accompanied by aggressive statements addressed to the editors. Journalists reported that there had been a number of cyber attacks on their email and social media accounts, beginning on January 28, 2022. The February 1 incident took place following a criminal case and associated protests against Kaktus.mediafor its reporting on the Kyrgyz-Tajik border conflict.

- On February 8, April TV journalist Yulia Kuleshova reported that unidentified individuals had gained access to her email account, Yandex 2FA details and mobile apps. “I don’t go to Yandex, and I definitely didn’t register anything there,” Kuleshova said. Shortly before that, there were attempts to hack her Facebook page and Telegram account.

- On February 8 and 9 in Bishkek, opponents of freedom of speech held rallies and conferences against independent media outlets. Protesters demanded that “the legislation against NGOs” be tightened, and that the Russian-style “foreign agent” label be applied, in particular to Kaktus.media, Radio Azattyk and Kloop.

- On April 22, Temirov Live journalist Aktilek Kaparov received two notifications about an attempt to log into his Telegram account. “They want to hack into my cart again, but today they logged in from two devices at once,” the journalist wrote. Attempts to hack his account were made from a Xiaomi Redmi A7 phone, both using the same IP address. Previously, hackers targeted the Telegram accounts of journalists from Kloop as well as other publications using the same model of phone.

- On October 4, the Facebook accounts of Kloop.kg journalists were hacked during a live broadcast of a meeting held by the President of Kyrgyzstan in the city of Uzgen in the south of the country. During the live stream, local residents expressed dissatisfaction with the upcoming transfer of the Kempir-Abad reservoir to Uzbekistan as part of an agreement between Bishkek and Tashkent to resolve ongoing border issues. The live stream was suddenly taken down and vanished from several reporters’ pages.

- On October 13, 40 protesters gathered near the office of Radio Azattyk in Bishkek and demanded the closure of Azattyk, Kloop.kg and Kaktus.media. A man in the crowd threatened journalists working for these publications and promised to “douse them with gasoline and burn down their offices.”

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

In 2022, there was a sharp increase in attacks against media workers via judicial and/or economic means. The most common methods of exerting pressure on journalists were interrogations, searches, confiscations and lawsuits. The number of such attacks has tripled since 2021. The number of attacks related to arrests and imprisonment increased significantly (from 3 to 19 cases). For the first time in the country’s history, 5 women journalists were simultaneously detained and held in a pre-trial detention centre. These journalists and activists were: Rita Karasartova, Asiya Sasykbaeva, Gulnara Jurabaeva, Klara Sooronkulova, Perizat Suranova.

The most noteworthy cases of 2022 include:

- On the evening of January 22, Bolot Temirov, editor-in-chief and investigative journalist at Temirov Live, was forcibly arrested in his office. Police officers, along with representatives from the Service for Combating Illicit Drug Trafficking and special forces soldiers, arrived at the office. Law enforcement conducted a search, confiscated equipment, including journalists’ computers and memory cards from security cameras installed in the office. Temirov was later charged under Article 283 of the Criminal Code of the Kyrgyz Republic (“illegal manufacture of narcotics without intent to sell”). Temirov Live journalists had previously investigated the fuel company owned by the family of the head of the Kyrgyz State Committee for National Security, Kamchybek Tashiev. On September 28, courts acquitted the journalist investigating the case of the charge of manufacturing drugs and illegal border crossing, but found him guilty of forging military documents. Due to the statute of limitations, no sentence was handed down. On November 23, Temirov was forcibly deported from Kyrgyzstan to Russia.

- On February 18, independent journalist Semetey Talas Uulu, who regularly reports on organised crime and corruption, was arrested at his home in Bishkek. Unidentified men dressed in civilian clothing searched his house and seized religious books. Later, the media, citing the press centre of the State Committee for National Security, reported that the journalist was detained and interrogated as part of a criminal case under the charge of “distribution of extremist materials”. After the interrogation, the journalist told his colleagues that the arrest was in response to his posts on Facebook. On November 3, he was placed under house arrest. On April 18, 2023, the Pervomaisky District Court in Bishkek sentenced him to a year of supervised probation.

- On March 3, Taalay Duishembiev, director of the independent channel Next TV, was arrested and sent to a temporary detention facility. Duishembiev was charged under Article 330 of the Criminal Code of the Kyrgyz Republic (“inciting racial, national and religious hatred”) for content the outlet had posted on Facebook and Instagram. According to investigators, the TV channel used social media to spread false information about the alleged agreement reached between Kyrgyzstan and Russia to provide the latter with military assistance in the war in Ukraine. Duishembiev was held in a pre-trial detention centre for 7 months, after which he was found guilty and sentenced to 5 years in prison. This was later changed to a 3-year non-custodial sentence, including a ban on leaving the country.

- On March 31, blogger Batmakan Zholbolduyeva was imprisoned in a pre-trial detention centre, having been accused of causing death by negligence. Arzygul Galymbetova, a 37-year-old journalist working for the AKIpress news agency, had died three days earlier. The Department of Internal Affairs reported that, on the day of her death, Galymbetova had approached the police with a statement that said Zholbolduyeva had slandered her online and damaged her reputation. On May 26, Zholbolduyeva was also charged with “violations of privacy,” “hooliganism” and “forgery of documents”. On August 18, Zholbolduyeva was placed under house arrest, and on February 4, 2023, she was sentenced to a further 2 years of supervised probation. The blogger was found not guilty of the death of Arzygul Galymbetova but was found guilty of the other charges she faced. As a result, she was banned from blogging.

- On June 16, Kuttumidin Bazarkuloa, the former head of the Jalal-Abad regional television and radio company, was charged with “abuse of an official position”. He had previously been arrested in November 2021 on suspicion of possessing illegal currency in 2015 and 2016, when he ran another television and radio company. The court fined Bazarkulov 3,215,000 Kyrgyz Som ($37,000). The journalist was released due to the statute of limitations.

- On June 30, Adilet Ali Myktbek (Adilet Baltabai), a well-known blogger and freelance correspondent for Next.TV, was arrested and taken to a pre-trial detention centre, where he was held for 2 months on suspicion of inciting riots. “I do not agree with the conclusions of the investigation and said so during the interrogation,” Adilet said. Two days before his arrest, the Pervomaisky police department in Bishkek summoned the blogger for interrogation as part of an ongoing criminal case under Article 278 (“Inciting riots”).

- On November 4, Sanrabiya Satybaldiyeva, a journalist from the MIR24 regional website, along with her videographer, were arrested and placed in a temporary detention centre. Satybaldiyeva was pregnant at the time of the arrest. Human rights activists reported that Sanrabiya was “taken to the maternity hospital and examined” by police officers. The journalist and videographer were detained “as part of a criminal case on inciting riots”. Prior to this, 25 activists, politicians, bloggers and journalists were arrested in Kyrgyzstan, having also been accused of inciting riots. Almost all the detainees were members of a committee formed to support the protection of the Kempir-Abad reservoir. The final decision in the case, following an agreement between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan regarding the settlement of border issues, was handed over to the latter.

- On August 19, Yrys Zhekshenaliev, administrator for the Polituznik Facebook page, was held in a pre-trial detention centre in Bishkek for 2 months. He was accused of inciting riots (“calling for active disobedience to the lawful demands of government officials, as well as calling for violence against civilians”). Prior to this, a search was conducted at Zhekshenaliev’s house, during which his mother’s laptop and SIM cards were confiscated. On August 14, 2022, Zhekshenaliev was summoned for interrogation at the Ministry of Internal Affairs following a post on Facebook that included an archived video message from the ex-chairman of the State Committee for National Security regarding the dispute surrounding the Zhetim-Too mineral deposits in the Naryn region bordering China.

In 2022, there were at least 20 recorded incidents related to the interrogation of journalists. These incidents included:

- On January 31, the prosecutor’s office of the Pervomaisky district of Bishkek summoned several Kaktus.media editors for questioning as part of a criminal case. Earlier, the Prosecutor General’s Office had initiated a criminal case under Article 407 (“conflict propaganda” or “the dissemination of information or ideas in any form that aims to bring about aggression between two countries”). This was in response to content reposted on the Kaktus.media site about the January 27 conflict on the Kyrgyz-Tajik border. The Prosecutor General’s Office claimed that the material contained “inaccurate claims that Kyrgyz forces started shooting first, which in turn provoked Tajikistan”.

- On June 5 and 7, Aizada Kasmalieva, head of Radio Azattyk, was interrogated about several articles posted on the site. She was told she had been summoned in order to “give information about the sources of, and reliability of, the information”. One of the articles in question focussed on Kyrgyzstan’s increasing national debt.

- On July 23, Aizhan Myrsiliyeva (Myrsan), a well-known blogger and activist, was summoned for interrogation on charges of inciting ethnic hatred. This followed a live broadcast in March 2022 that focused on “illuminating the problem of nationalism in everyday life”. She claims that the video, which was the basis for the accusations against her, was edited.

In 2022, there were 4 recorded cases of media outlets being blocked or shut down:

- On March 4, opposition TV channel Next TV was shut down, and employees of the State Committee for National Security blocked off its offices. The channel’s documentation and equipment was confiscated in its entirety. The State Committee for National Security accused Next TV of inciting ethnic hatred. According to investigators, the channel “spread false information about the alleged agreement reached between Kyrgyzstan and Russia to provide the latter with military assistance in the war in Ukraine, referring to the former head of the Kazakh intelligence service as ‘a source of information’”. The State Committee for National Security considered this to be “a catalyst for inciting ethnic hatred and hostility based on nationality”.

- On July 21, following a decision taken by the Kyrgyz Ministry of Culture, Information, Sports and Youth, the independent media website ResPublica.kg was blocked. Journalists at the publication had spent the previous 2 years investigating corruption at the Manas International Airport in Bishkek, uncovering a corruption scheme between the airport’s management, intermediary companies, and high-ranking officials. In 2021, according to the findings of a journalistic investigation, the ex-president of Manas Management, Asan Toktosunov, was arrested by the State Committee for National Security on corruption charges. He made a deal with the investigators, and also paid them $200,000 in compensation. Following this, Toktosunov sued ResPublica for publishing false information.

- On August 26, the Service for Regulation and Supervision at the Communications Industry contacted internet providers, demanding that the 24.kg website be blocked for 2 months. Officials cited the law on “inaccurate (false) information,” without indicating on which article the claim was based. Earlier, the Minister of Culture, Azamat Zhamankulov, said the department had received ‘the first complaint about the publication on social media”. As a result, some providers blocked the 24.kg website for approximately 2 hours. When the Ministry of Culture was approached for comment, they claimed that the decision to block the website had already been withdrawn.

- On October 26, authorities blocked the Radio Azattyk website for 2 months, citing the law on protection from false information. The move was in response to a video posted on Current Time titled “Heavy Fighting on the Border of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan”. It was alleged that the material “contradicted the national interests of the Kyrgyz Republic, and contained inaccurate information about the events of September 14-17, 2022, as well as hate speech and discrimination”. Despite statements from lawyers, human rights activists and media experts about the legitimacy of these charges, on April 28, 2023, courts ruled to close the editorial offices of Radio Azattyk.

ANNEX 1: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (KYRGYZSTAN)

- 24.kg – a website, a news agency covering events in Kyrgyzstan;

- Bulak.kg – an online media outlet;

- Freedom House – a non-profit organization group in Washington, D.C. It is best known for political advocacy surrounding issues of democracy, political freedom, and human rights.

- Kaktus.media – an online media outlet covering events in Kyrgyzstan;

- Kloop.kg – an online media outlet covering and analysing events in Kyrgyzstan;

- Knews.kg – a news agency, news and analysis;

- National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic – the central statistical office of the country;

- Radio Azattyk – the Kyrgyzstan service of Radio Liberty, providing daily coverage and analysis of events in Kyrgyzstan;

- Reporters Without Borders – an international non-profit and non-governmental organization that safeguards the right to freedom of information;

- School of Peacemaking and Media Technology in Central Asia – a non-profit organisation specialising in research in the sphere of media, annual ratings of freedom of expression, and media monitoring;

- Telegram channels and social media accounts of Kyrgyzstan’s journalists, bloggers and media outlets.