AUTHOR OF THE REPORT: SCHOOL OF PEACEMAKING AND MEDIA TECHNOLOGY IN CENTRAL ASIA

PHOTO: Journalists Makhabat Tazhibek kyzy, Azamat Ishenbekov, Aktilek Kaparov and Aike Beishekeeva during court hearing wearing t-shirts with the inscription “The truth bends, but does not break”.

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Kyrgyzstan, 145 attacks/threats against professional and civil media workers, and the editorial offices of traditional and online media outlets were identified and analysed in the course of the study for 2024. Data for the study was collected using content analysis from open sources in three languages: Kyrgyz, Russian and English. Reports were also analysed of incidents sent by media workers directly to the Justice for Journalists Foundation. A list of the main sources is provided in Appendix 1.

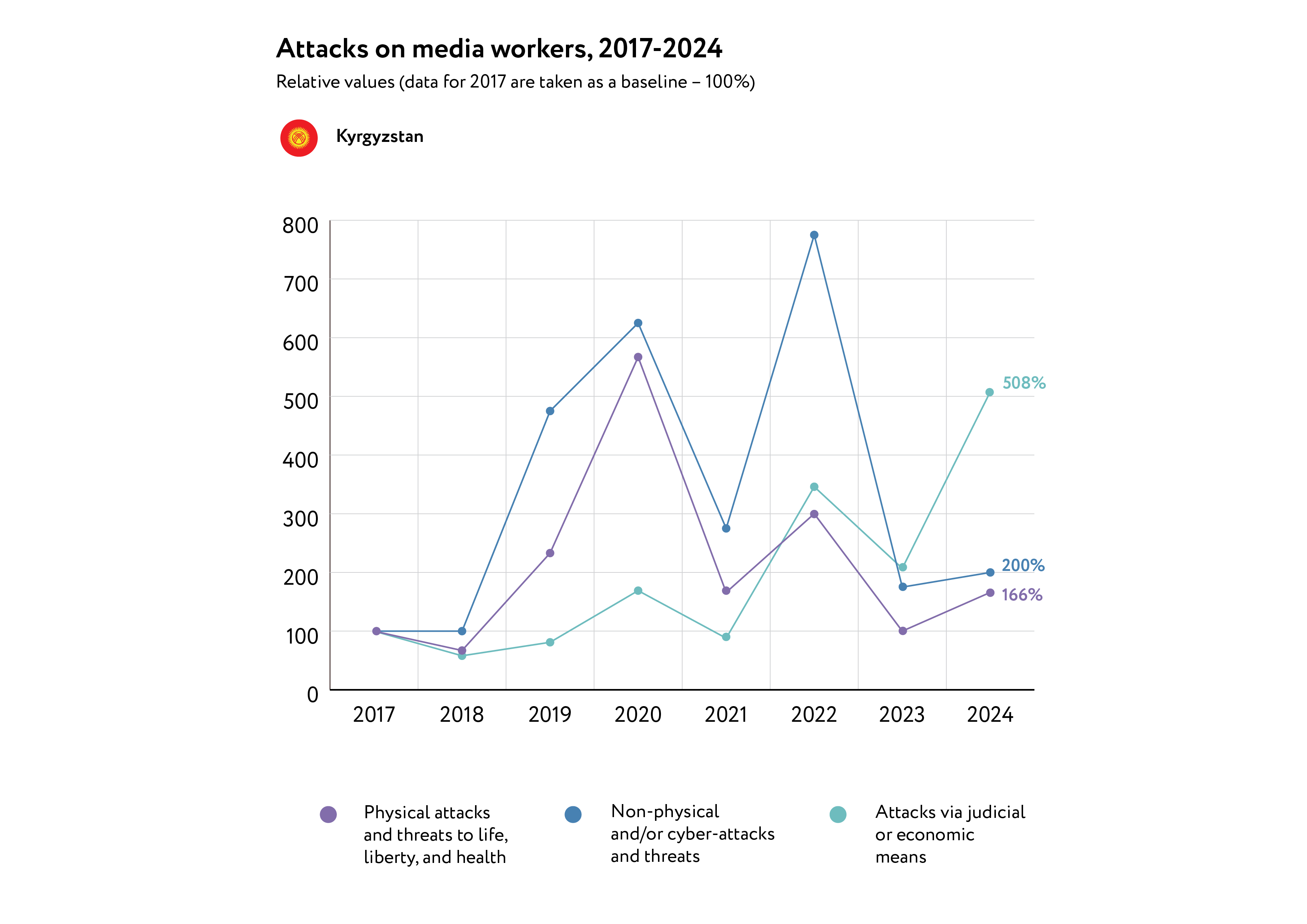

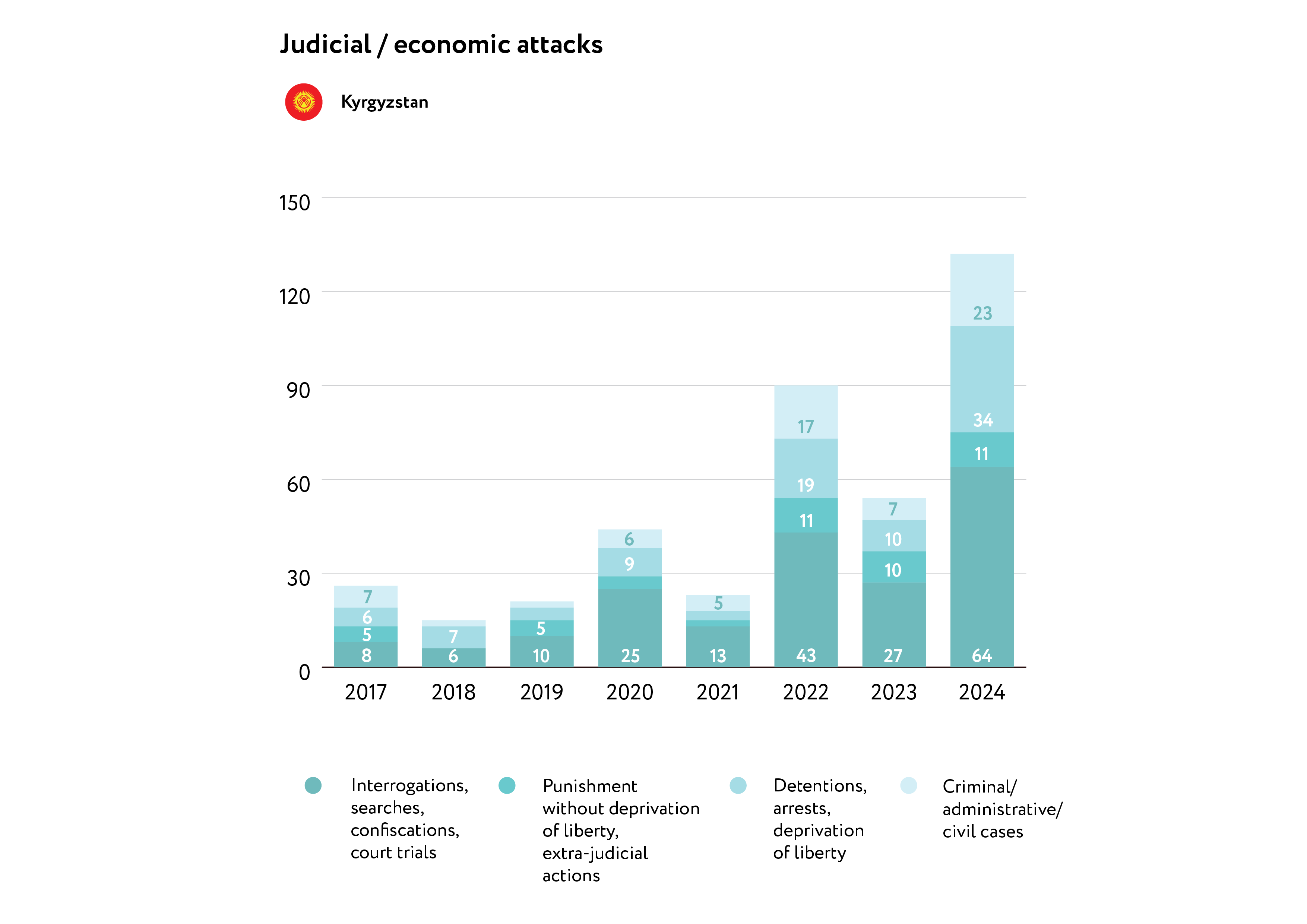

- As in previous years, attacks via judicial and/or economic means remained the main type of pressure on media workers. In 2024 there was the largest number of such attacks for the past 7 years.

- In 2024, the authorities continued to actively apply the practice of confiscating property from editorial offices, organizing surveillance and imprisoning their critics for “disobedience” and “calls for mass riots”.

- The largest scale of arrests in the history of Kyrgyz journalism took place in January 2024, with 11 investigative journalists from the YouTube channels, Temirov LIVE and Ait Ait Dese, arrested after searches in their homes and offices. All of these journalists had exposed corruption and fraud among the highest authorities of Kyrgyzstan. In October 2024, four of the eleven arrested journalists received prison sentences.

- Political censorship increased in the country in 2024, after the adoption of the law “On Foreign Representatives” (analogous to the Russian law “On Foreign Agents”), introduced in order to crack down on independent media.

- In February, the Oktyabrsky Court of Bishkek ordered that the independent Kloop.Media, which regularly published various investigations and critical materials, be closed down. The reason given was that Kloop.Media was “carrying out activities that go beyond the scope provided by the charter”.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN KYRGYZSTAN

According to the 2024 annual Press Freedom Index published by the international NGO, Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Kyrgyzstan ranked 120th out of 180 countries. Somewhat curiously, this was two places higher than in the previous year. However, Kyrgyzstan remains a country where the situation with press freedom is assessed as “difficult”. RSF emphasizes that the Kyrgyz government “still controls all traditional media and is trying to extend its influence to privately owned media, whose situation has become critical”.

In 2024, the authorities continued to pass laws restricting press freedom. The law “On Foreign Representatives” has complicated the work of the media, since some outlets are officially registered as NGOs. The bill duplicates 95% of a similar Russian act. It provides for the mandatory re-registration of media outlets within two months and the complete closure of those outlets that have not passed the re-registration criteria. All websites fall under the category of media, and anti-corruption investigations may be banned. A new draft law on media has still to be adopted after the sixth version put before parliament was sent back to be revised.

Another bill which is expected to be adopted soon would make it illegal to film or photograph police officers. In November, members of parliament almost unanimously supported the bill. According to MPs, such filming is done “with the aim of discrediting the authorities”. After the final adoption of the bill, such actions will become punishable by a fine or arrest.

Throughout 2024, the authorities significantly increased political censorship. At the beginning of the year, the Ministry of Culture, Information, Sports and Youth Policy sent out letters to media outlets, signed by the Deputy Minister, Chyngyz Esengul uulu, recommending what journalists may and may not write.

“When covering events happening in the country and around the world, we ask you to observe the principle of political neutrality on foreign policy issues, taking into account the position of Kyrgyzstan on the world stage. Also, avoid publishing material that may affect the domestic political situation in neighbouring states, as this may violate the principles of good neighbourliness and negatively affect bilateral relations”, the letter says.

The Ministry of Culture acts as a kind of “supervisor of the media”, since it is empowered to label information as false, recommend what and whom should be blocked, oversee censorship and deal with citizens’ complaints. In particular, in November, the Ministry of Culture initiated an inspection of the independent television channel, Next TV, based on a written complaint from a viewer who said that the channel is spreading negative information which can provoke “protest moods”.

In 2024, aggressive rhetoric towards independent media continued to come from senior people in the authorities, who consider independent media and non-profit organizations as a threat to the regime. For example, in December, speaking at the Kurultai (People’s Assembly formed by the authorities and consisting of loyal delegates), President Sadyr Japarov expressed his dissatisfaction with the fact that the US State Department provides funds to support independent media and human rights organizations. He even listed the amounts received by such outlets as Azattyk.Media, Kaktus.media, PolitKlinika, Govori.TV and Kloop.Media. Somewhat sarcastically, Japarov declared:

“I would like to address the top officials of the US State Department. If you don’t know what to do with your money, transfer the funds directly to us and we will distribute them accordingly. If you want us to boost journalism to a high level, we will. If freedom of speech is needed – we’ll make sure it’s in place. We’ll spend your money efficiently, we will not deceive you and we will report to you on the work done”.

At the end of 2024, the penalty for libel was reinstated. At the initiative of the Cabinet of Ministers, amendments were made to the Code of Contraventions on administrative fines for libel and defamation. According to the new amendments, complaints regarding libel must be sent to law enforcement agencies – in other words, the Ministry of Internal Affairs – after which they will become legal cases and sent to court. Human rights activists say the new law could become a tool for suppressing public criticism.

Commenting on the arrest of the publicist, Olzhobai Shakir, the Deputy Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers, Edil Baisalov, said that the purpose of the arrest was to teach him a lesson. “This is an educational measure. In some cases, the state has to stick to its functions, we must bring the public to their senses”, he stressed.

According to the Unified State Register of Statistical Units, there are about two thousand business entities registered as mass media in Kyrgyzstan and 158 independent television and radio companies. Similar data is provided by the National Statistical Committee of Kyrgyzstan in the latest annual catalogue for January 2023.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

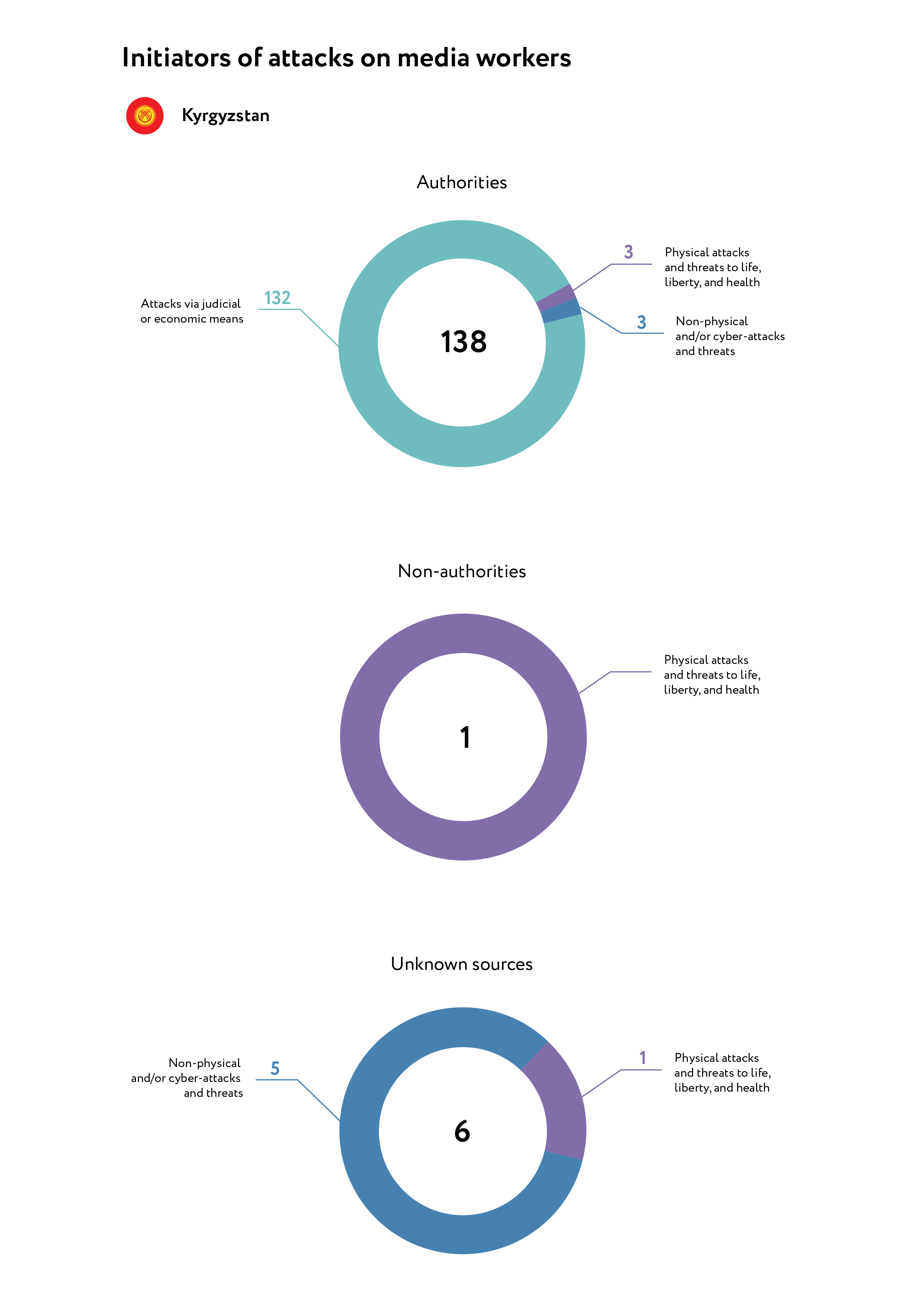

In 2024, 145 attacks/threats were recorded against journalists, bloggers, media workers, and the editorial offices of traditional and online media. 95% of these attacks came from government officials. In 2024, a record number of incidents involving attacks via judicial and/or economic means was recorded – twice as many as in 2023.

Most of the recorded incidents were related to journalistic investigations, coverage of sensitive events and live broadcasts of bloggers on current topics. Cases were recorded of a blogger being tortured with electric shocks and of sexualized violence. Other documented incidents include widespread hacking of journalists’ accounts, fraudulent tricks to simulate “bribe-taking” and bullying.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

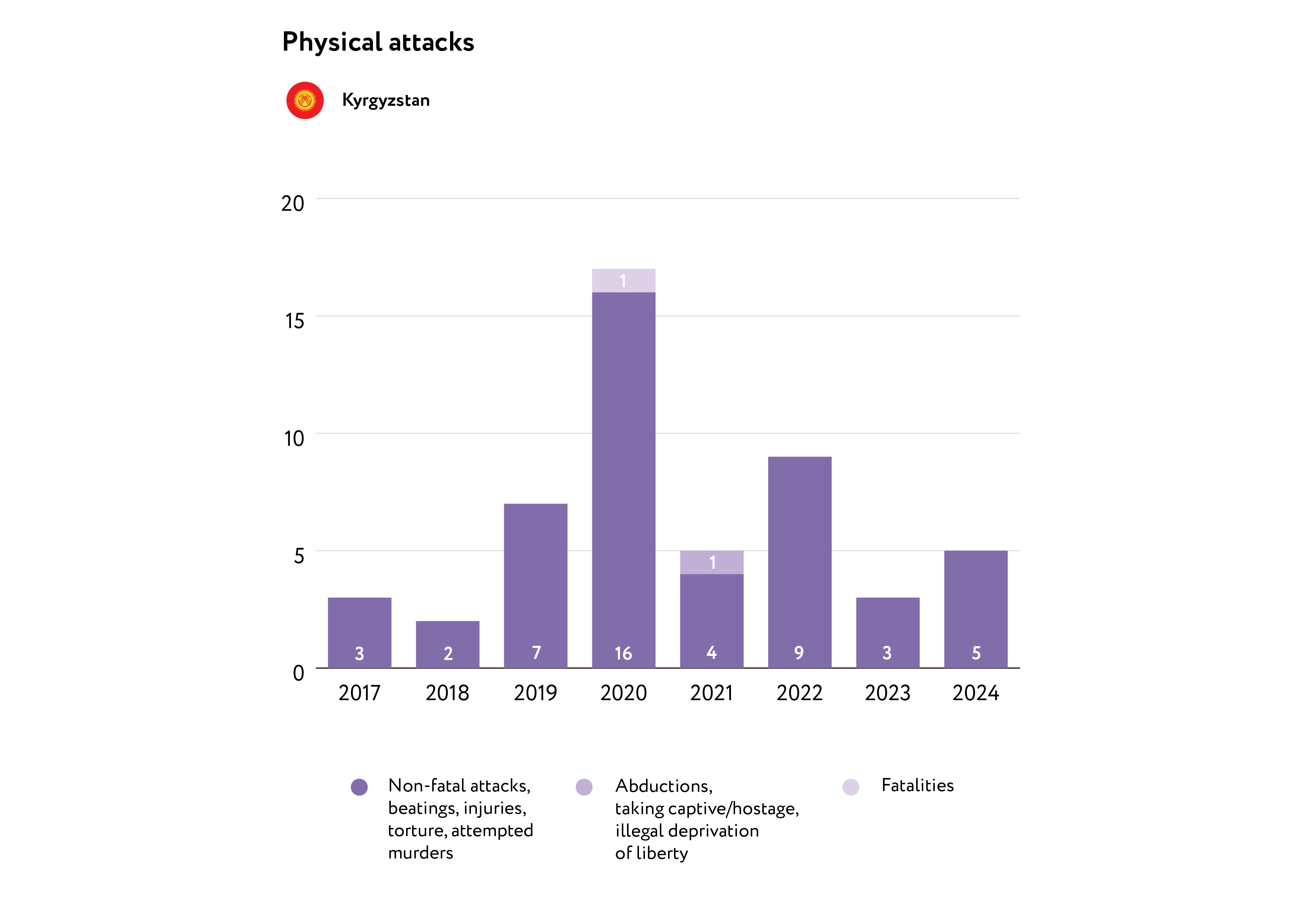

In 2024, five physical attacks were recorded. Journalists have been subjected to mistreatment, attacks and torture while in prison for their professional activities.

- On December 25, blogger Batmakan Zholboldueva told her audience during a live broadcast on Facebook that in April 2022 she had been raped while she was in a temporary detention centre. She said that when she was washing she was raped by a man who had served time in prison for murdering a police official. Zholboldueva believes that the rapist was sent to her by the head of the detention centre after she had had a verbal altercation with him. This was followed by another rape attempt, after which she cut her veins with a blade. Following this incident, the officials of the district and regional prosecutor’s office promised to take action, but no investigation was carried out and the perpetrators were not brought to justice.

Other recorded incidents in 2024 include:

- Makhabat Tazhibek kyzy, the head of the Temirov Live project, was tortured and beaten while she was in a pre-trial detention centre on April 6, and her ill-treatment was recorded. She had been arrested along with ten other media workers in January. Representatives of the National Centre for the Prevention of Torture visited the pre-trial detention centre, documented the signs of mistreatment and abuse and accepted her statement. Earlier, her husband, Bolot Temirov, the founder of TemirovLive (a team of investigative journalists), reported on social media that his wife had been beaten by an employee in the pre-trial detention centre.

- On May 23, blogger and poet Askat Zhetigen, who was charged under the articles of “mass riots” and “calls for the seizure of power”, reported that after his arrest he had been tortured by officers of the State Committee for National Security. He was given electric shocks for an hour in the basement of the state security service building. The blogger reported that he had been tortured to the Ombudsman of the Kyrgyz Republic and the National Centre for the Prevention of Torture of the Kyrgyz Republic. Zhetigen was detained in March in the Kochkor district of the Naryn highland region and taken to the capital, Bishkek. Since 2021, Zhetigen has been publishing video messages criticizing the government.

- Aktilek Kaparov, is an investigative journalist who was arrested in January along with Makhabat Tazhibek kyzy (see above) and nine other colleagues of the Temirov Live YouTube channel. On May 30, he cut his wrists in the pre-trial detention centre as an act of protest and sent a “bloody letter” which was published by several media outlets. In his letter, Kaparov stated that he had been illegally deprived of his liberty for five months, demanded release and said that he had made an attempt to cut his veins. The letter was published as an image with some visible red spots which could be the journalist’s blood.

- On October 25, the imprisoned blogger, Zarina Torokulova, was placed in a punishment cell (SHIZO) for carrying out minor renovation work on dilapidated rooms in the prison dormitory. The prison administration considered this a violation. She was bullied and kept for 15 days in the SHIZO, where conditions are much worse than in regular cells. In January 2024, she had been found guilty of “calls for active disobedience to the lawful demands of representatives of the authorities and mass riots” after reposting two messages on Facebook and was sentenced to five years in prison. In December, Torokulova’s terms of imprisonment were upgraded to a strict high-security level.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

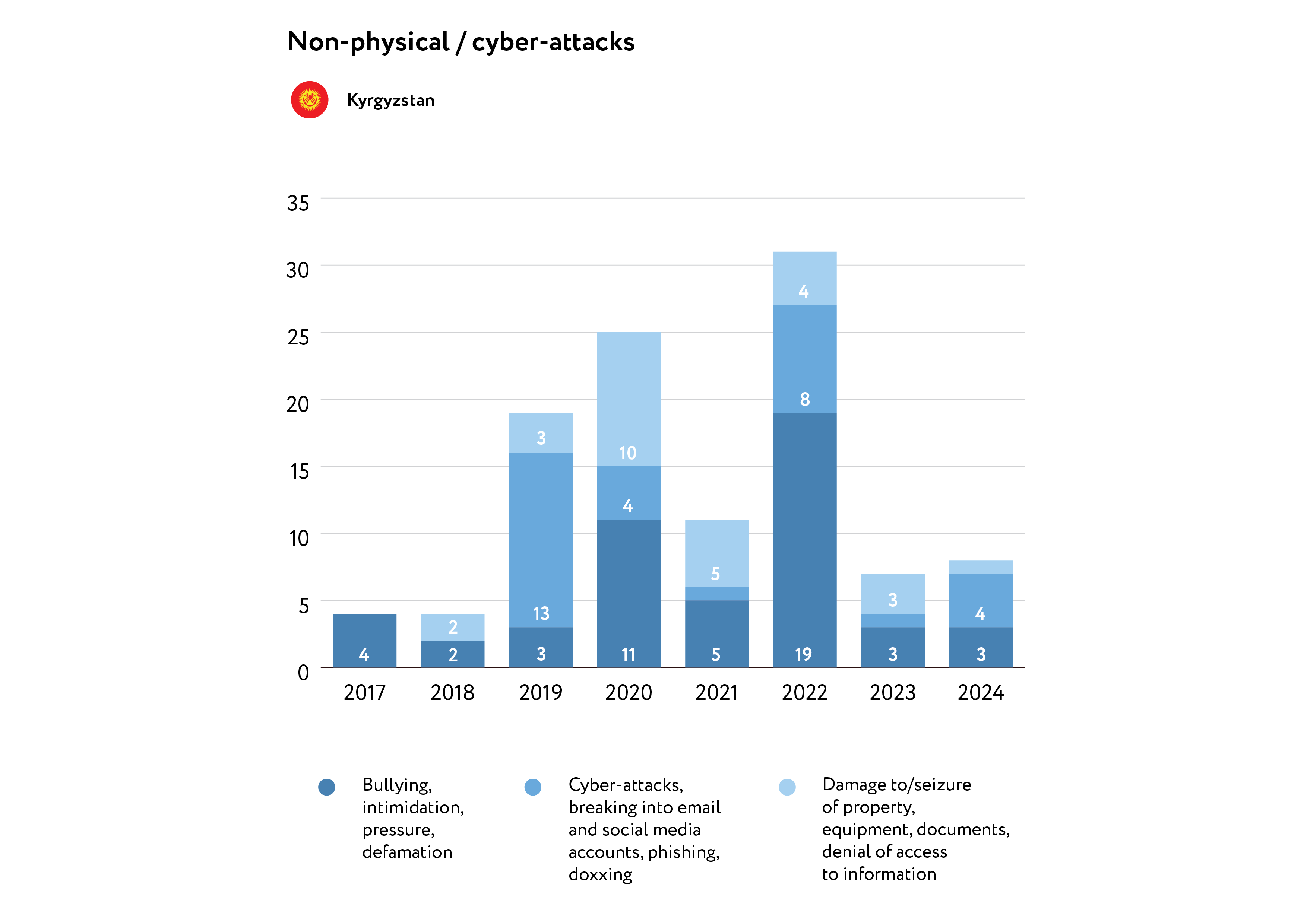

In 2024, eight incidents were recorded in this category. The most common methods of pressure were non-physical attacks, cyberattacks and harassment of media workers, including threats and intimidation.

- In February, there were repeated attempts to hack the Telegram account of Kaiyrgul Urumkanova, the head of the independent news agency Govori.TV. On her Facebook account, she posted a number of screenshots, on which an attempt to log in to her Telegram account can be seen, indicating devices and IP.

- Also In February, a similar attempt was made to hack the Telegram account of Dilbar Alimova, the editor-in-chief of the outlet PolitKlinika. Alimova wrote on her Facebook page that the hacking attempts were conducted from the same IP address, using the same device. This happened while the parliamentary committee on constitutional legislation, state structure, judicial and legal issues and regulations was discussing the repressive draft law “On Media”. PolitKlinika is an independent media outlet that conducts high-profile journalistic investigations related to corruption in the highest echelons of power.

- On November 4, an attempt was made to hack the Telegram account of Yulia Kuleshova, a journalist from the independent April TV channel. She also noticed that there was an attempt to delete her account. Before this happened, there had been an unlawful attempt to obtain information about the journalist. Two men in civilian clothes, posing as law enforcement officers, were making enquiries about her from the head of the housing association where she lives. They also spoke to some of her family members.

- A similar incident occurred with another journalist of the April TV channel, Alesya Tsurikova. There were several active attempts to hack her social media accounts. This happened after unknown individuals, introducing themselves as representatives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, came to her home and asked her neighbors about her. Checks showed that they did not represent any of the law enforcement agencies, and soon after the incident, active attempts began to hack her social media accounts. At the same time, she was receiving calls from unknown numbers.

- On June 30, blogger Gulperi Janyshbek kyzy reported that she had received threats by phone and on social media, including from the authorities of the Kara-Suu district (Osh region in southern Kyrgyzstan). She had been posting material critical of them on her social accounts. A few days later, she was detained and placed in a pre-trial detention centre in Osh on charges of extortion.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

The number of attacks via judicial and/or economic means doubled in 2024 compared to 2023. There has also been a sharp increase in the number of arrests of media workers and the initiation of criminal cases against them under such articles as “calls for mass riots”, “hooliganism”, “extortion”, “extremism” and “incitement to hatred”.

Massive searches and detentions were carried out in January. Eleven journalists associated with the YouTube channel Temirov Live and the subsidiary project Ait Ait Dese were arrested. Among the detainees were Makhabat Tazhibek kyzy, Aktilek Kaparov (see above, section 4, for each journalist), Sapar Akunbekov, Azamat Ishenbekov, Saypidin Sultanaliev, Tynystan Asypbekov, Maksat Tazhibek uulu, Joodar Buzumov, Zhumabek Turdalia, Aike Beishekeyeva and Akyl Orozbekov. All of them had been investigating corruption and the family businesses of the top authorities.

A criminal case was opened against them, based on accusations of “calls for protests and riots”. The journalists were detained for 48 hours, after which the Pervomaisky District Court of Bishkek ordered a further two months of detention in a pre-trial detention centre.

In March-April, six of the eleven arrested (Joodar Buzumov, Maksat Tazhibek uulu, Saypidin Sultanaliev, Tynystan Asypbekov, Saparbek Akunbekov and Akyl Orozbekov) were released under house arrest, and another one – Zhumabek Turdaliev – was released by the court on his own recognizance. But Makhabat Tazhibek kyzy, the head of the AitAitDese project, was sentenced to six years in prison; Azamat Ishenbekov, blogger and poet, to five years, Aktilek Kaparov and Aike Beishekeyeva to three years on probation. Seven other defendants in the case were acquitted by the court.

Almost at the same time as the arrests and searches of the 11 journalists, a search was carried out at the editorial office of the independent news agency, 24.kg, as part of a criminal case initiated under the article “War Propaganda”, because they had published information about the war in Ukraine. The State Committee for National Security (SCNS) confiscated documents and computers of the agency’s employees. Lawyers were not allowed to be present at the search. The agency’s manager, Asel Otorbaeva, and two chief editors, Makhinur Niyazova and Anton Lymar, were interrogated twice, and the office was sealed for two months. When it became known that the agency had new owners, the equipment was returned to the office, and the criminal case was suspended all together by the State Committee for National Security.

Other incidents involving arrests of journalists/bloggers include:

- On January 16, the Pervomaisky District Court of Bishkek sentenced blogger Zarina Torokulova to five years in prison. (See above, section 4.) She was accused of reposting a video on Facebook entitled “Organizing an online rally”, by the renowned journalist and publicist Oljobai Shakir. At the time that Torokulova reposted the video, Olzhobai Shakir himself was in a detention centre, for “calls for mass riots” and “an attempt to seize power”.

- The blogger Kanykei Aranova, who is known for raising issues related to the lands of the Kempir-Abad reservoir, was detained in Moscow on February 1, and deported to Kyrgyzstan. Her 11-year-old daughter was also taken to the airport directly from her Moscow school. On February 5, the Pervomaisky District Court of Bishkek arrested Aranova, and charged her under the articles “Public calls for the violent seizure of power” and “Incitement of racial, ethnic, national, or religious interregional hatred”. On April 25, the court gave her a fine of approximately $1500, and released her from the detention facility, but ordered a recognizance not to leave as a preventive measure. But in June the court decided to make her penalty stricter and sentenced her to 3.5 years in prison.

It should be noted that in December Zarina Torokulova and Kanykei Aranova, who had been incarcerated in a women’s prison, were transferred from a general regime colony to a prison intended for persons convicted of crimes of a terrorist and extremist nature. These prisons also house people convicted for posts on social networks, in particular, on charges of calling for mass riots and seizing power. This is happening despite numerous reminders by human rights activists that, according to earlier amendments to the legislation, those convicted of taking part in hostilities in another country, terrorism, extremism, murder and other serious crimes, should be kept in a separate facility.

- On March 17, Askat Zhetigen, a famous Facebook blogger and folk storyteller, was detained. He was arrested by investigators from the State Committee for National Security in the Kochkor district of the Naryn highland region of the country, for criticizing the authorities in the form of folklore satire. He was brought to Bishkek and interrogated several times, after which a criminal case was opened against him on charges of “calls for a violent seizure of power”. In July, the Sverdlovsk District Court of Bishkek found the blogger guilty and sentenced him to three years in prison. On his Facebook page, he had posted various video messages criticizing the actions of the current government. In particular, he spoke out against such moves as the legalization of gambling; changing the flag of the Kyrgyz Republic; the imprisonment of activists; and reforms in the cultural sector.

Prison was not the only punishment used against media workers. Some were also sentenced to house arrest and fines, were banned from engaging in professional activities and put on probation:

- On February 9, the State Committee for National Security detained the blogger Batmakan Zholboldueva and placed her in a pre-trial detention centre on suspicion of extortion. (See above, section 4.) She was later transferred to house arrest. Zholboldueva was examining the sanitary condition of canteens and shops in the Bakten region in the southwest of the country, as well as checking the expiry date of goods. She published videos of her trips and findings on her YouTube channel “Batma-bat,” which has about 100 thousand subscribers.

- Also on February 9, the independent journalist, Ermek Attokurov, was arrested on suspicion of extorting 1 million Kyrgyz soms (approximately $11,000 USD) from a law enforcement official. A few days before his arrest, Attokurov wrote on social media that police were preparing a “provocation” against him. After some time, the journalist was put under house arrest, and later fined 30 thousand Kyrgyz soms ($260 USD) by the court.

- The blogger Ali Ergeshov was detained at the Manas International Airport in Bishkek on February 13. He runs the YouTube channel “El Bilsin”, where he talks about the quality of services, the sanitary condition of catering and publishes citizens’ appeals about various violations in the Jalal-Abad region in the south of the country. Ergeshov was detained by order of the Jalal-Abad City Court as part of a criminal case initiated against him on charges of hooliganism, which allegedly occurred in May 2023. He posted on Instagram that he is certain that his detention is directly related to his professional activities. A few days later, the blogger was released under house arrest, and in May given a fine “for hooliganism”.

- On May 14, the Alamudun District Court of Chui Province sentenced Shakir Oljobai, a well-known journalist and publicist, to five years in prison on charges of “inciting mass riots”. Shakir was detained in August 2023 and has been in custody ever since. He is accused of “calls for active disobedience to the legitimate demands of representatives of the authorities, and mass riots”. On the eve of his arrest, he raised his voice in opposition to the authorities’ decision to hand over to Uzbekistan four holiday resorts in the area of Lake Issyk-Kul. In October, a Supreme Court reviewed his case and sentenced him to three years on probation.

- The Sverdlovsk District Court of Bishkek released blogger Aftandil Zhorobekov on June 15, and placed him under house arrest. Zhorobekov was detained by police officers in December 2023. He was charged with “calls for active disobedience to the legal demands of representatives of the authorities, and for mass riots” under the Criminal Code of the Kyrgyz Republic. Prior to his arrest, Zhorobekov planned to hold a rally and a motor rally against the government’s plan to change the national flag. He was also summoned to the State Committee for National Security for questioning regarding the campaign he carried out on social networks.

- On June 30, blogger Gulperi Janyshbek kyzy was arrested on suspicion of extortion. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, a citizen had filed a complaint against her with the police. After her arrest, she was placed in a temporary detention centre in Osh, the southern capital of Kyrgyzstan. Gulperi herself claims that the persecution against her was staged by the head of the local government of the Kara-Suu district, Osh region. On July 2, the court released her under house arrest.

- The journalist and blogger Adyl Akzhol uulu was summoned to the State Committee for National Security of Osh for questioning on July 29. At 17:09 p.m., he received a call from the department with a demand to come in immediately for interrogation. Akzhol uulu asked the officers to postpone the interrogation until the next day, but in response he was told in a threatening way that it would be better for him to arrive without delay. The reason for the summons was not explained to him at the time.

- On June 20, journalist Bayan Zhumagulova was summoned for questioning in relation to her Facebook posts. Later, a criminal case was opened against her under the article “Incitement of racial, ethnic, national, or religious interregional hatred” of the Criminal Code of the Kyrgyz Republic. During the interrogation, her phone was taken away and all data downloaded by the officials. She is a former employee of Azattyk, but retired several years ago, lives in Germany, and in early June flew to Kyrgyzstan, where she almost immediately came under pressure from law enforcement agencies.

Several incidents related to warnings, pre-trial claims, informal interrogations and other extra-procedural actions were also recorded:

- On November 20, the editorial office of the independent TV channel, Next.TV, was subjected to a surprise inspection by the Ministry of Culture on the basis of a complaint received from a viewer who was unhappy with “the channel’s dissemination of negative information” that in turn could provoke “protest moods”. The complainant also drew the attention of the Ministry of Culture to the fact that the channel rebroadcasts programs of foreign and local origin produced with “foreign funding”. In particular, the complainant meant the output of such media as Current Time, Azattyk and the investigative outlets PolitKlinika and T-Media. The owner of Next.TV and the opposition politician, Ravshan Dzheenbekov, said on social media that he regards the actions of the Ministry of Culture as “deliberately organized pressure on the independent media” and on himself. Dzheenbekov has been persecuted by the authorities for several years.

- On December 13, an “obstruction of journalistic activity” was recorded against Azattyk employees. Journalist Maksat Kutmanbekov and camera person Nurlan Beishebaev were filming near the pre-trial detention center-1 in Bishkek and interviewed relatives of those under investigation. The journalists were working on a report on a mass hunger strike by inmates in a number of prisons and pre-trial detention centres in protest against the appointment of a new head of the Penitentiary Service. While they were filming, police officers approached Kutmanbetov and Beishebaev, and demanded that they delete the video. After they refused to do so, they were taken to the police station. They were released only after a “preventative conversation” and the submission of an explanatory note of their actions, which the journalists had to write by order of the law enforcement agencies.

- On February 9, 2024, the Oktyabrsky District Court of Bishkek ruled that Kloop.Media, the legal entity of the online outlet of the same name, should be shut down. The court’s decision was directed against a specific clause in the outlet’s charter, which says that it “provides youth and other representatives of civil society with an information platform to freely express their opinions on social, political and economic processes”. According to the court, such a clause does not allow the organization to operate as a media outlet. The second reason for shutting down the organisation that the court focused on is that Kloop.Media does not carry “civil responsibility” for its publications which causes “an increase in the number of citizens with mental disorders”.

ANNEX 1: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (KYRGYZSTAN)

- 24.kg –website and news agency covering events in Kyrgyzstan

- PolitKlinika– website covering news and posting investigative media reports

- Freedom House –non-profit organization group in Washington, D.C. It is best known for political advocacy surrounding issues of democracy, political freedom, and human rights

- Kaktus.media – an online media outlet covering events in Kyrgyzstan

- Kloop.kg – an online media outlet covering and analysing events in Kyrgyzstan

- Knews.kg – a news agency, producing news and analysis

- Mediazona – an online media outlet

- National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic – the central statistical office of the country

- Radio Azattyk – the Kyrgyzstan service of Radio Liberty, providing daily coverage and analysis of events in Kyrgyzstan

- Reporters Without Borders – an international non-profit and non-governmental organization that safeguards the right to freedom of information

- School of Peacemaking and Media Technology in Central Asia – a non-profit organisation specialising in research in the sphere of media, annual ratings of freedom of expression, and media monitoring

- Telegram-channel “Breaking Kloop” – Telegram channel of an online media outlet Kloop known for its news website and journalistic investigations

- Telegram channels and social media accounts of Kyrgyzstan’s journalists, bloggers and media outlets