AZERBAIJAN

AUTHOR OF THE REPORT: KHALED AGHALY, LAWYER AND SPECIALIST IN MEDIA LAW IN AZERBAIJAN

PHOTO: TURAN NEWS AGENCY

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Azerbaijan, 215 incidents of attacks/threats against media professionals and citizen journalists, editorial offices of traditional and online publications, and online activists were identified and analysed in the course of the research for 2021. Data for the study were collected using open source content analysis in Russian, Azerbaijani and English. Information about some incidents was obtained directly from the journalists and bloggers in question, or their lawyers. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 2.

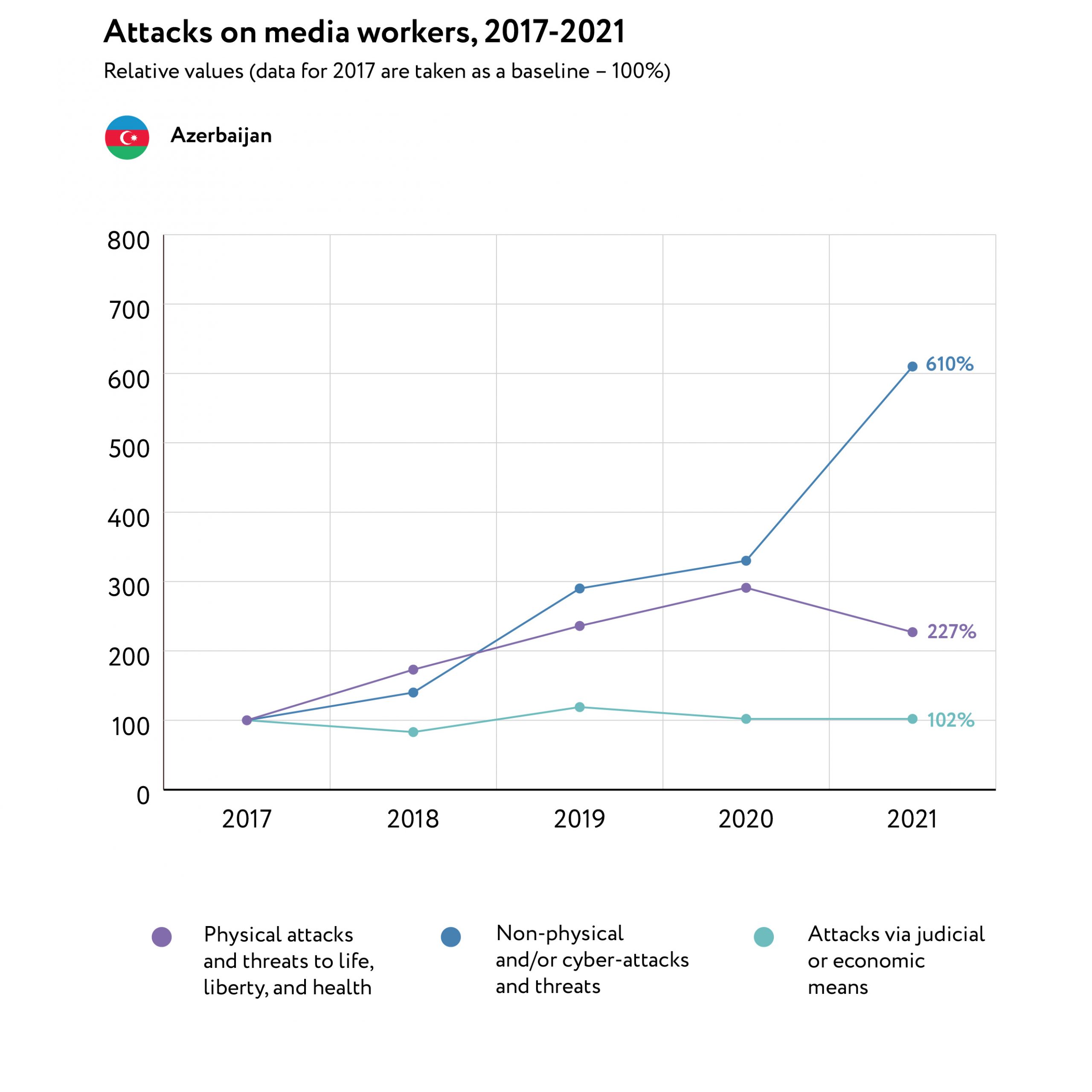

- 2021 saw a slight increase in the total number of attacks, up to 215 from 194 in 2020.

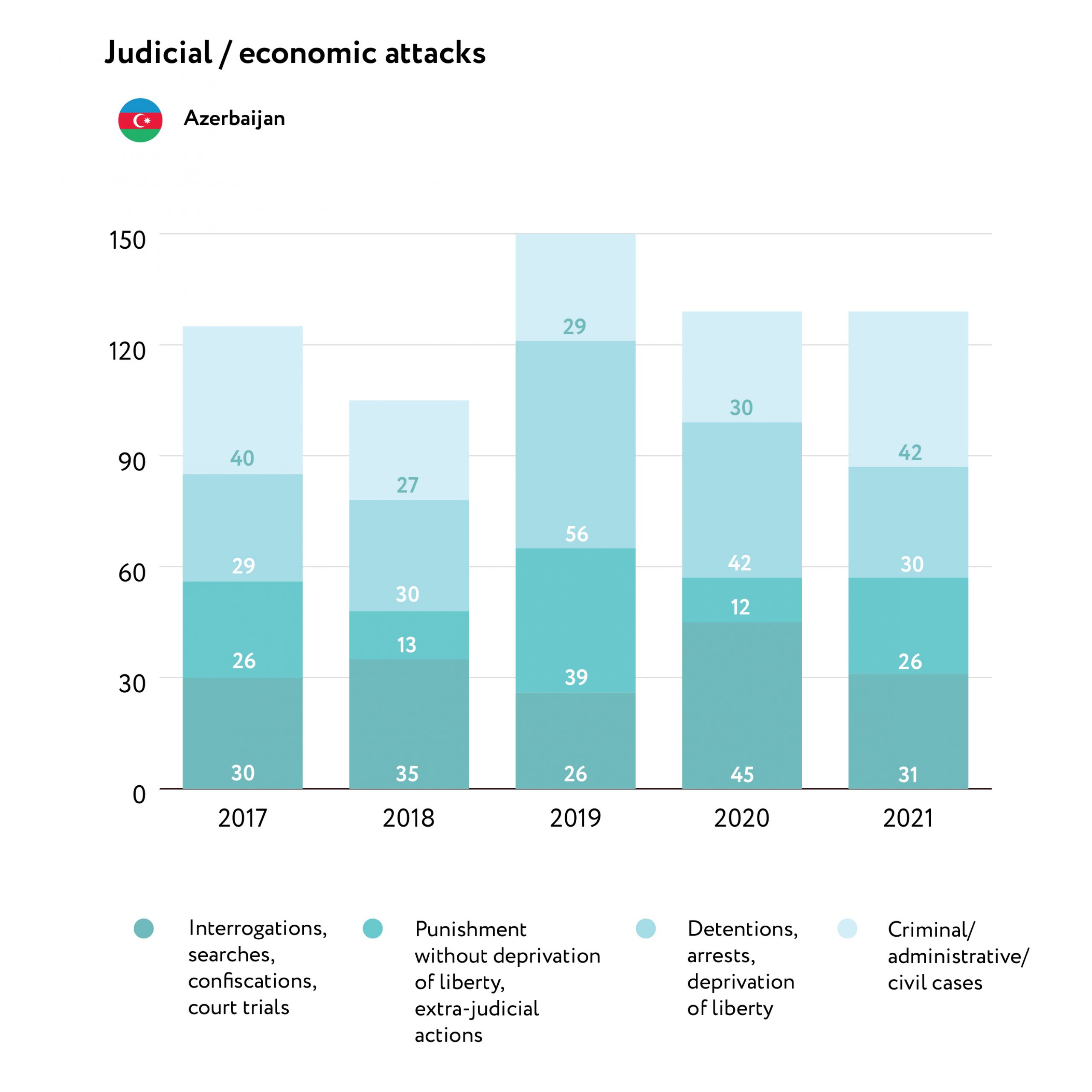

- Pressure was most frequently exerted via judicial and/or economic means. In this category, there were 129 incidents, 60 percent of the total number of attacks.

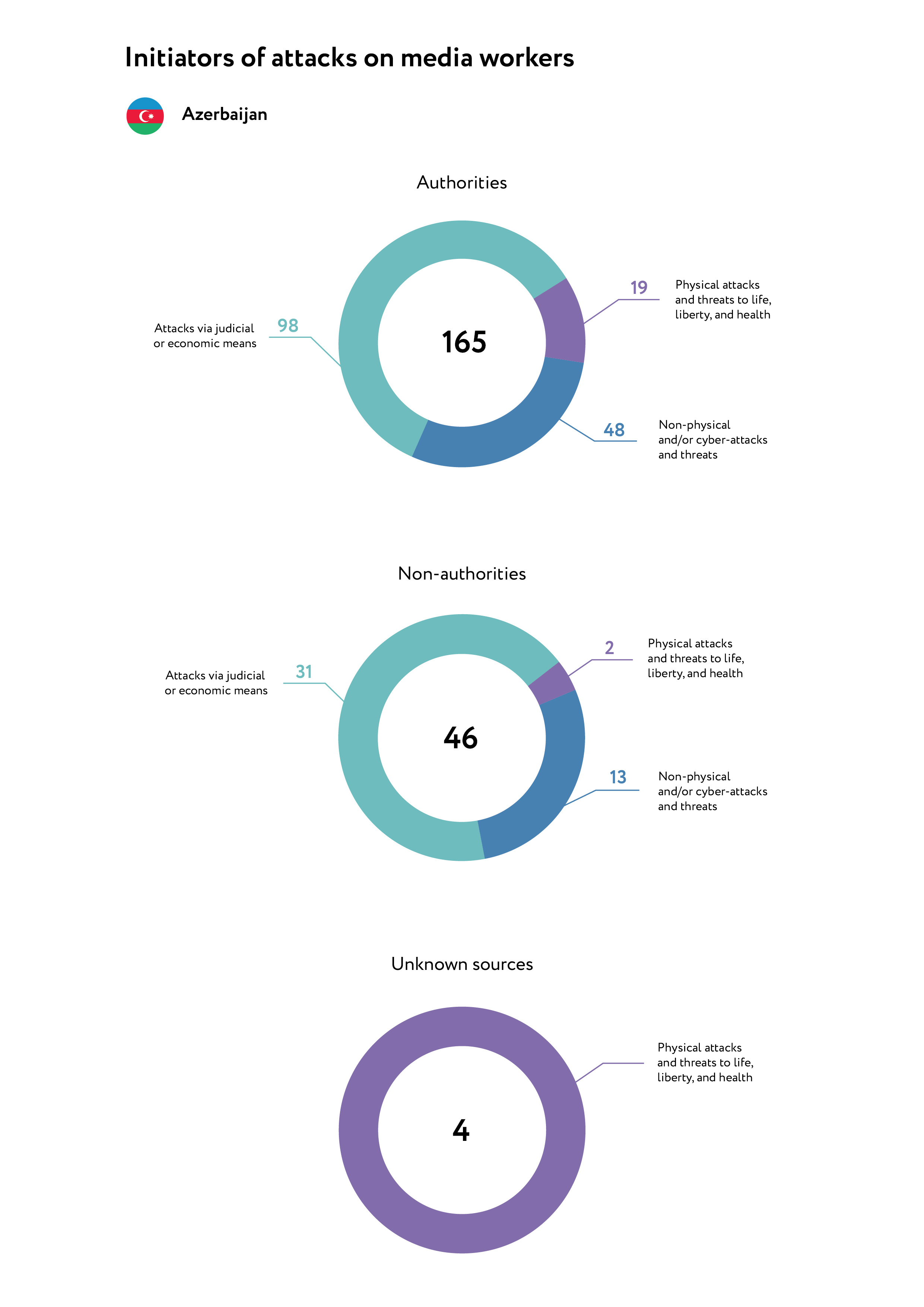

- In 76 percent of cases, attacks on media workers were committed by government officials.

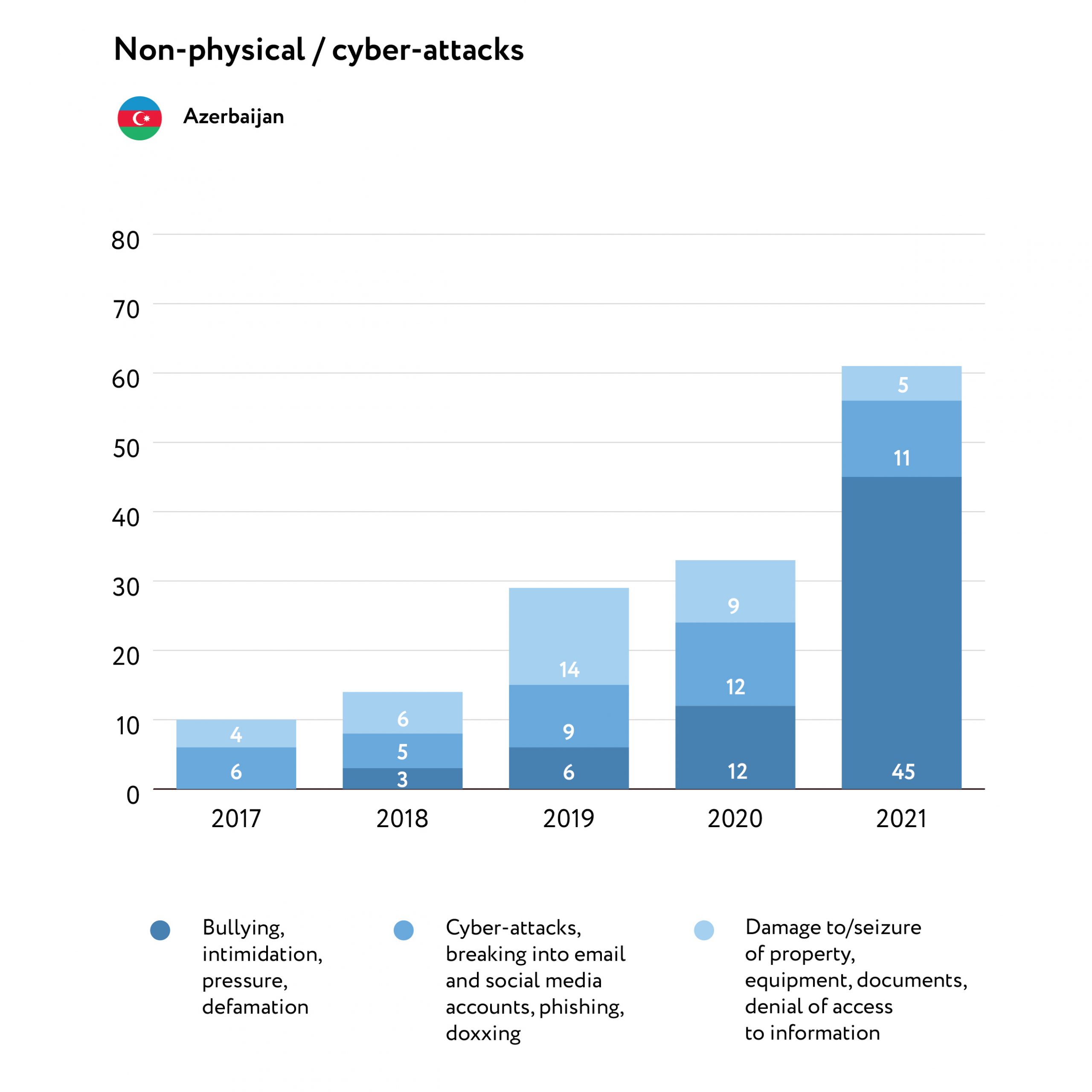

- There was a two-fold increase in the number of non-physical attacks, many identified through the publication of information about mass surveillance of independent journalists and activists by the Azerbaijani authorities.

- In 2021, law enforcement agencies did not prosecute any of the individuals responsible for attacks on media workers. Investigations into attacks on journalists were often inadequate.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN AZERBAIJAN

Media freedom in Azerbaijan remained in a dire position in 2021. In the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index for 2021, the country was ranked 167th out of 180. In 2020, Azerbaijan ranked 168th.

In its Freedom on the Net 2021 report, the US-based non-governmental organisation (NGO) Freedom House classified the internet in Azerbaijan as “not free”, with the country scoring 35 points out of a possible 100. The report notes that the country had issues relating to internet speeds, the information and communication technologies sector remained under state control, authorities manipulated information online and attempts to distribute information which is critical of the authorities were blocked. Azerbaijan was also classed as a “not free” country in Freedom House’s 2020 report on internet freedom. In the NGO’s 2017 report, the internet in Azerbaijan was considered to be “partially free”, scoring 42 out of a possible 100 points.

According to official sources, over 5,000 media outlets were registered in Azerbaijan in 2021. There were, in fact, about 500 functioning mass media organisations. These media outlets, despite attempts at self-regulation were all, in some way or another, under government control.

In early 2021, the Media Development Agency was established to provide support to both online and print media. This was previously the responsibility of the State Media Support Fund, but the new agency functions in a similar way. Funds are allocated from the state budget and distributed via grant competitions to media organisations. Previously, only print media was dependent on this funding, however online media, which was largely free from state control and mainly funded by grants from donor organisations, has now found itself reliant on state funding.

There are 94 radio and TV broadcasters in Azerbaijan: 11 national TV broadcasters, 11 regional TV broadcasters, 16 radio broadcasters, two satellite TV broadcasters, 17 cable network operators, 35 IPTV operators and two operators broadcasting foreign TV channels via satellite. The broadcasting sector is regulated by the National Television and Radio Board, which was created, funded and controlled by the government. The Council is periodically allocated funds from the state budget, which it distributes among broadcasters.

Print and broadcast media, both of which depend on government funds, are fully controlled by the government. Since business in the country also remains closely connected to the government, independent and opposition media are deprived of advertising revenue.

At the end of 2021, a new phase of legal regulation of the media in Azerbaijan began. On December 30, the Azerbaijani parliament adopted a new media law, despite objections from local journalists and the international community. The previous laws (“On Mass Media” and “On Television and Radio Broadcasting”), which regulated the work of print and broadcast media, were nullified. The new laws allow for strict regulation of the media, including stipulations on the legal status of journalists and online video broadcasts.

Analysis of the attacks on media workers in Azerbaijan in 2021 revealed that the main problem facing journalists, bloggers, and media workers in the country was the ineffectiveness of legal protection. Journalists are, in theory, protected from external interference by law in Azerbaijan. Violence against a journalist carrying out their professional duties, for instance, is a criminal offence, while withholding “socially significant information” from a journalist is an administrative offence. In practice, however, none of these laws are followed.

Large-scale attacks on independent media organisations and journalists are usually carried out in the following ways:

- Blocking online media outlets. Current laws allow sites to be blocked for minor issues such as unverified information and reporting on suicide. This usually takes place without a court’s involvement, which, in turn, makes it nearly impossible to reverse.

- Hacking. Opposition media organisations, individuals posting content criticising the authorities, and journalists’ social media profiles are often hacked.

- Criminal penalties for defamation. Laws criminalising defamation continue to be used to censor “objectionable” content.

- Civil lawsuits to protect honour and dignity. Judicial practice in cases such as these is typically not in favour of media organisations or journalists. The courts accept all claims against media workers, even without sufficient grounds or evidence.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

In 2021, 215 attacks against journalists, bloggers and other media workers were recorded in Azerbaijan. This number increased almost one and half times since 2017. Attacks via judicial and/or economic means remained the most common method of exerting pressure on media workers. The number of attacks of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks doubled in 2021 from 2020. This followed the revelation that the Azerbaijani authorities used the “Pegasus” spyware from the Israeli “NSO Group” to spy on independent journalists and activists. At least 43 incidents of this kind have been recorded.

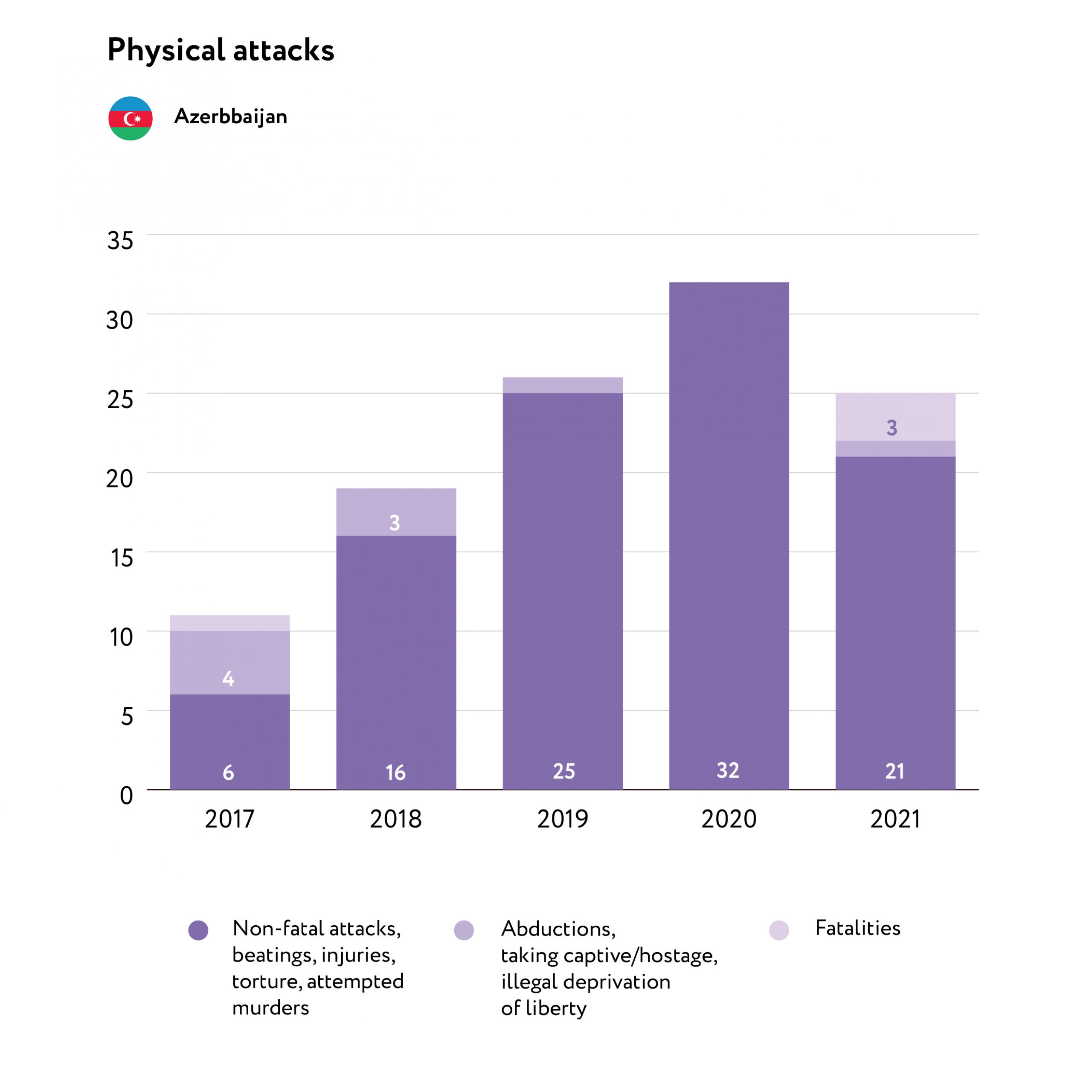

There has been a slight decrease in the number of physical attacks against journalists, bloggers and other media workers. In 2019, 32 cases were reported. This number fell to 26 in 2020 and 25 in 2021.

In 76 percent of cases, representatives of the authorities were responsible for the attacks. In 11 percent of cases these attacks came from individuals who were former representatives of the authorities.

The most common attacks on media representatives in Azerbaijan in 2021 consisted of attempts to interfere with their professional duties. Independent and opposition journalists were often forcefully detained, their professional equipment confiscated or damaged, and footage deleted. There were 50 incidents of this nature in 2021.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

In 2021, at least 22 incidents of physical attacks on journalists were recorded in Azerbaijan. Three journalists were killed.

- On January 21, editor and founder of Qərb bölgəsi press and Qərb.TV online, Aliyev Bakhtiyar, was killed in the Shemkir region. The murder was committed by close relatives. The incident reportedly happened on domestic grounds.

- On June 4, an Azerbaijan State Television (AZTV) employee, Siraj Abyshov, and an employee of the state AZERTAJ agency, Maharram Ibrahimov, were killed after their car drove over a mine. The journalists were preparing to report from the area, where fighting had taken place during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war. Another AZTV employee, Emin Mammadov, was injured following the explosion.

In 2021, one journalist was kidnapped.

- On July 29, Arshad Ibragimov, editor of the dunyanınsesi.az (Voice of Peace) website, was forced into a car and taken away by individuals in civilian clothes. According to the journalist’s brother, Tariel Ibragimov, Arshad was detained by the Ministry of Internal Affairs for Combating Organised Crime. “Since he’d only received a phone call, my brother refused to go [to the police station]. He demanded that they send him an official summons,” said Tariel, who believes his brother was detained for criticising the police. The head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ media and public relations department, Elshad Hajiyev, said that “Ibragimov was invited to the police station following a citizen’s request and, after writing a statement, will be released.”

Most of the journalists who were subjected to physical attacks in 2021 were representatives of opposition independent media outlets. Most attacks took place while they were reporting on protests held by various opposition political groups.

- On March 8, a women’s march was held in Baku under the slogan “March 8: for our rights”. During the demonstration, reporter Nurlan Gahramanli was assaulted while filming a group of activists who were being arrested.

- On May 7, four journalists were physically assaulted during a rally held by a group of war veterans in central Baku. Police stopped them from filming and detained the protesters. Independent journalists Nurlan Gahramanli, Zahra Kalantarova, Avaz Hafizli and Vusala Gasangyzy were not allowed report, and their professional equipment was seized.

- On May 14, Nurlan Gahramanli was detained by police while asking about the arrest of his colleague, journalist Elmeddin Shamilzade. Both journalists were held at the police station, charged with “petty hooliganism” and fined. Gahramanli and Shamilzade were treated in a physically rough manner by police.

- On August 4, Microskop Media employee Elnara Gasimova, Voice of America (VoA) correspondent Ulviyya Ali, and independent journalist Nargiz Absalamova were physically assaulted while reporting on a demonstration held by a group of women’s rights activists outside the police headquarters. The journalists spent several hours in police custody. They said that they were subjected to physical and mental abuse, the content of their phones was examined and they were forced to delete video footage.

- On October 5, a group of activists from the Popular Front Party of Azerbaijan (PFPA) held a protest in front of the Azerbaijani Penitentiary Service. The activists demanded the release of PFPA member Niyameddin Akhmedov, calling on local media and human rights activists to raise awareness of the arrested PFPA members. The reporters covering the demonstration, including Meydan TV journalist Aysel Umudova, Microskop Media journalist Zarifa Novruzova, and Turan TV employee Fatima Movlamli, showed their IDs, but were detained by force, nonetheless.

- On November 5, Turan TV journalist Fatima Movlamli was detained during another PFPA demonstration outside an Azerbaijan Penitentiary Service medical institution. She later reported that she was verbally abused and assaulted while in police custody.

- On December 1, Baku TV journalist Tural Museibov was publicly assaulted by guards while trying to interview the head of the State Border Service.

- On December 28, around 30 independent media journalists held a demonstration in front of the main parliament building. There was a clash between police and the protesters, in which journalist Nargiz Absalamova’s collarbone was broken.

In 2021, the majority of physical attacks on journalists involved police officers. The law protects journalists from such attacks, and explicitly prohibits the persecution of media workers. In 2021, journalists reported 10 incidents of this kind to the prosecutor’s office and demanded that charges be pressed against their attackers. None of these requests were granted.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

There were at least 61 incidents of attacks of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks against the editorial offices of online news organisations, journalists, bloggers and other media workers in 2021. There has been a significant increase in noted cases of harassment, intimidation and defamation in connection to the revelation that the Azerbaijani government spied on journalists.

In the summer of 2021, the Organised Crime and Corruption Research Centre (OCCRP) published an investigation into the hacking of journalists’ phones in Azerbaijan using the Pegasus spyware. Several journalists whose phones were tapped filed complaints with law enforcement agencies, but no investigations were carried out.

According to the OCCRP, the Azerbaijani government used spyware to monitor at least 43 prominent journalists:

- Avaz Zeynalli, Khural newspaper, Editor-in-chief

- Azer Aykhan, Yeni Musavat media group, Journalist

- Aziz Karimov, Photographer for Turan, Getty Images, Associated Press, Time Magazine, BBC and Reuters

- Aydin Dzhaniev, Khural newspaper, Journalist

- Aynur Jamalgyzy, Teleqrafmedia group, Director

- Ainur Elgunash, Meydan TV, Journalist

- Aytan Mammadova, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Journalist

- Aytan Farhadova, Meydan TV and Institute for War and Peace Reporting, Freelance journalist

- Anar Orudzhev, Channel 13, Founder

- Arif Aliyev, Pressklub.az, Executive Director

- Bahaddin Gaziev, “Bizim Yol” (“Our Way”), Editor-in-chief

- Vahid Mustafayev, ANS TV, Journalist, Film Director

- Vidadi Mammadov, Azadliq, Journalist

- Vusala Mahirgizi, APA News Agency, Director General

- Ganimat Zahid, Turan TV, Manager

- Gular Mehdizade, Freelance journalist

- Jasur Sumerinli, Journalist

- Zamin Haji, Musavat.com, Journalist

- Zahir Azamat, qaynarinfo.az, Editor-in-chief

- Inara Rafiggizi, AzeriDaily.com, Journalist

- Islam Shikhali, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Journalist

- Mehman Aliyev, Turan News Agency, Director

- Mir Shahin Agayev, Real TV, Executive Director

- Mushfig Jabbar, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Journalist

- Natiq Javadli, Meydan TV, Journalist

- Parviz Hashimli, gununsesi.info, Editor

- Ramin Deko, Radio Azadliq, Journalist

- Rauf Arifoglu, Yeni Musavat newspaper, Editor-in-chief

- Rovshan Hajilbayli, Azadliq newspaper, Editor-in-chief

- Sevinj Vagifgizi, Meydan TV, Journalist

- Seymur Kazymov, Freelance journalist

- Sujaddin Sharifov, Azadliq newspaper, Deputy editor-in-chief

- Tazakhan Miralamli, Azadliq newspaper, Journalist

- Fizza Heydarova, Radio Azadliq, Journalist

- Khadija Ismailova, Investigative journalist

- Khalig Bahadir, Azadliq newspaper, Journalist

- Shahveled Chobanoglu, Journalist

- Eynulla Fatullayev, Haqqin.az, Executive Director

- Elkin Khalilov, Freelance journalist

- Elnur Astanbeyli, Publicist, poet

- Elkhan Shukurlu, Strateq.az, Editor-in-chief

- Elchin Shikhly, Chairman of the Union of Journalists of Azerbaijan; ayna.az, Executive Director.

2021, as was the case in previous years, saw several cyber attacks against opposition activists, including:

- On August 27, the HamamTimes website was hacked. Employees reported that hackers removed all the content from the site. They were able to restore the site’s archive, but their vulnerability to cyber attacks remains.

- On September 14, the news page of the opposition Musavat Party on Facebook was hacked. Similar incidents occurred in the past. The same day, a private Facebook group, Azad Azərbaycan, was hacked and taken down.

In at least three cases, journalists’ inboxes and social media profiles were hacked:

- On August 7, Turan.az reported that the Realliq.tv Facebook page, as well as the personal page of Realliq.tv editor Ikram Rahimov, had been hacked. “All profiles are managed by an outside group, I do not have access to the profiles”, said Rahimov. He also said that Youtube had informed him of attempts to hack into the Realliq.tv channel.

- On September 4, the editor of the news website anews.az, Naila Balaeva, reported that her Facebook account had been hacked. The email address and phone number, to which the profile was linked, were changed. Although Balaeva was able to regain access to her emails, the hacker continues to access her Facebook, often deleting critical posts about the police or government agencies.

- On November 3, according to Alasgar Mammadli, the founder of Toplum TV, unknown individuals hacked into his phone and gained access to Toplum TV’s Facebook account. They also managed to access Mammadli’s private information and correspondence. The attackers deleted videos from the “Debate in Society” program, which featured leaders of the PFPA and Musavat opposition parties. In addition to this, thousands of subscribers were removed from the Toplum TV page.

Journalists, especially members of opposition media organisations, were often interfered with while trying to gather information. For example:

- Elshan Balakhansky, an employee of the Novy Musavat newspaper, Anar Mammadov, head of the kriminal.az website, and Haji Zeynalov, an employee of the Bizim Yol newspaper, were prevented from gathering information at the trials of former leaders of the Ministry of National Security, which took place on November 16 and 19. Despite these being ostensibly open trials, a panel of judges prevented independent journalists from entering the courtroom.

There was one recorded case of a non-physical attack on a journalist’s friends and family in 2021.

- On March 5, Azerbaijani video blogger Mohammed Mirzeli was blackmailed. Mirzeli, who emigrated to Europe a few years ago, is known for his Youtube channel in Azerbaijan, where his family members still live. In recent years, his relatives were routinely subject to persecution. His parents and close relatives have been arrested in the past. In March, he was sent explicit images of his sister and demands were made that Mirzeli quit journalism, otherwise these photos would be published.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

In 2021, at least 129 attacks via judicial and/or economic means were recorded against media representatives and organisations in Azerbaijan. In 98 of these cases, these attacks were committed by government officials.

The main methods of exerting pressure were initiations of criminal, administrative and civil cases (41 incidents) and interrogations, searches and confiscation of belongings (31 incidents). Examples of such incidents are:

- On August 10, Fuzuli Mammadov, president of the İnter Sever group and head of the Union of Russian Azerbaijanis, filed a lawsuit against the head of Xural TV. The businessman also sued Reaksiya TV and its head, Zaur Gariboglu, over several publications. The court ordered the journalists to apologise, remove the offending material and pay compensation to Mammadov.

- On September 8, Mammadov filed a civil lawsuit against Khural TV and Reaksiya TV alleging they spread “slanderous” information about him. The Binagadi District Court partially sided with Mammadov. It ordered Khural TV to pay 350 Manat (US $200) to the plaintiff, while Reaksiya TV was ordered to pay 230 Manat (US $135). In addition to this, both media outlets were ordered to remove the offending materials from their sites.

- On October 19, five members of the Religious Workers of Azerbaijan association were detained: Sardar Babayev, Gadir Mammadov, Jalal Shafiyev, Ali Musayev and Tamkin Jafarov. The individuals contributed to the website maide.az. According to their relatives, the arrests were carried out by employees of the State Security Service. Their phones and computers were also confiscated.

- On November 6, head of the Citizens and Development Party, Ali Aliyev, and the head of the Bumerang Media Youtube channel, Elchin Rahimzade, were interrogated by the State Security Service. They were eventually released. Aliyev told reporters the interrogation was linked to a “large-scale criminal case” but could not disclose any further details. Rahimzade said a search was carried out at the editorial office, a safe was confiscated, and he was interrogated as a witness. Police were interested in the sources of some of the videos published on the channel.

Slander and defamation are criminal offences in Azerbaijan, which forces journalists into a position of self-censorship. In 2021, media organisations and journalists were prosecuted at least 20 times for defamation. In most cases, these lawsuits were initiated by officials, employees of government agencies and government-aligned businessmen. Examples include:

- On January 26, Rasim Mammadov, chairman of the NGO Coalition of Public Control, filed a lawsuit against journalist Aygun Muradkhanli for slander and humiliation (Article 147 of the Criminal Code) and demanded that she be arrested. Mammadov argued that the journalist accused him of separatism, fraud and other crimes on Facebook and Youtube.

- On March 2, the Sheki Court of Appeal sentenced bloggers Elchin Hasanzade and Ibrahim Turksoy to eight months in prison on charges of defamation. Both were taken directly into custody following the trial. The lawsuit was filed by the head of the city housing and maintenance department, Shakhriyar Mustafayev. The lawsuit stemmed from critical publications about the official on social media. The Mingachevir court previously sentenced both bloggers to a year of forced labour. On November 2, 2021, Hasanzade and Turksoy were released from prison, having served their sentence in full.

- On March 29, the Khachmaz District Court considered a case against freelance journalist Jamil Mammadli. The lawsuit was filed by the chief executive of the neighbouring Guba region, Ziyaddin Aliyev, who demanded that the journalist be brought to justice under Article 147.2 of the Criminal Code (false accusations of committing a serious crime).

- On April 28, Rafil Israfil oglu Huseynov, head of the Agjabadi regional executive power, filed a lawsuit against independent journalist Khayyam Salmanzade under Article 147 of the Criminal Code (defamation). The journalist wrote articles criticising Huseynov’s actions during the war. Huseynov demanded an apology from the journalist, and a payment of 300 Manat (175 USD) The complaint was later withdrawn.

- On April 28, businesswoman Arzu Babayeva filed a lawsuit against Parvin Abyshova, editor-in-chief of Aztimes.az, under Article 147 of the Criminal Code. Aztimes.az published information about Babayeva’s illegal activities. Babayeva maintained her innocence and demanded an apology, and 10,000 Manat (US $5,800) in compensation.

- On June 22, the Akhsu District Court held a preliminary hearing of a lawsuit filed by the State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) Vice President, Mikayil Ismayilov, against blogger Elshan Alisoy. Ismailov pressed charges under Articles 147 (defamation) and 148 (committing offence) of the Criminal Code. Alisoy shared an Azadsoz.com article entitled “The Dark Empire of Mikayil Ismayilov” on Facebook, with the comment, “God, why do they need so much money… Mikayil Ismayilov is one of the 12 vice-presidents of SOCAR. It’s greedy and barbaric.” The blogger said, “After I posted this, Ismailov filed a lawsuit against me and wants me to pay 100,000 Manat [US $60,000] for causing moral damage,” the blogger said.

- On July 8, the Swiss Prosecutor’s Office opened a criminal case against Azerbaijani bloggers and journalists living in Europe. This followed a lawsuit, filed by SOCAR, for defamation and damages to their reputation. The case was opened against blogger Fuad Agayev, who published an expose about SOCAR’s leadership. The head of Turan TV, Ganimat Zahidov, editor Fikret Huseynli, manager Emil Jafarov, and bloggers Azer Kazimzade, Orkhan Agayev, Gabil Mammadov and Muhammed Mirzeli are all named in the case. SOCAR demanded the arrest and extradition of these individuals to Azerbaijan.

- On August 9, the head of the legal department of the National Academy of Sciences, Kamal Aliyev, demanded the arrest of Avaz Zeynalli, head of Khural TV. On March 3, the request was considered in the Baku Court of Appeal. Aliyev, claimed that Zeynalli slandered him and demanded that Zeynalli be tried under Article 147.2 of the Criminal Code (false accusations of committing a serious crime).

- On September 16, Ilgar Aliyev, the cousin of the President of Azerbaijan, and Ilham Almas oglu Mammadov sued Avaz Zeynalli, editor-in-chief of Khural TV, for slander. They claimed that the journalists slandered them during an interview. Their complaint was accepted by the courts.

In 2021, at least 16 incidents were recorded related to the arrest of journalists carrying out their official duties. The following journalists were arrested: Tazakhan Miralamli (Azadlıq newspaper), Nurlan Libre (freelance reporter), Salima Jalilova (Turan agency), Sevinj Sadigova (Azel.tv), Aytaj Tapdyg (Meydan TV), Mehman Huseynov (blogger), Ulvi Hasanli (abzas.org), Elmeddin Shamilzade (Toplum.tv), Nargiz Absamalova (abzas.org), Ulviya Ali (VoA), Elnara Gasimova (Microskop Media), Aysel Umudova (Meydan TV), Fatima Movlamly (freelance journalist), Zarifa Novruzova (Microskop Media) and Teymur Kerimov (freelance journalist). The majority of these incidents took place in the centre of Baku.

Since 2021, a new trend has emerged in Azerbaijan, with the application of repressive legislation originally introduced in 2017. This includes amendments to the law “On Information, Informatisation and Protection of Information” and to the Code of Administrative Offences, which directly impact the activities of media organisations and journalists and allows significant room for abuse. The amendments prohibit the dissemination of information that allegedly promotes suicide, is offensive or libellous or violates the privacy or intellectual property rights among other restrictions. These articles were introduced into the Code of Administrative Offences. This legislation, which came into effect in December 2021, violates the right to freedom of expression guaranteed by the Constitution of Azerbaijan, as well as the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. Under these new laws, ordinary citizens can be prosecuted for online posts. Opposition journalists have been targeted. For example:

- On December 18, the news website manevr.az and journalist Sakhavet Mammad, who writes about the military, were prosecuted under Article 388-1.1.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences and fined 500 Manat (US $300).

- On December 18, the Prosecutor General’s Office announced the introduction of measures against various media organisations and social media users. “Due to the constant dissemination of false and biased information on social media, on December 16 and 17, Abushov Zamig, Mahmudov Ilgar, Ibrahimov Mehti and Safarsoy Rza were brought to the Prosecutor General’s Office and given official warnings,” a statement from the Prosecutor General’s Office said. The olke.az and manevr.az websites were also fined 1,500 Manat (US $880) under Article 388-1.1.1, for dissemination of “propaganda and promotion of suicide.”

In 2021, the practice of imprisoning journalists under dubious charges continued. For example:

- On April 20, a court in Baku sentenced Talysh blogger Aslan Gurbanov, who was arrested by the State Security Service in June 2020, to seven years in prison for “inciting national hatred.” Gurbanov was found guilty of “inciting hatred towards the state”, as well as “inciting hatred on national, racial, social and religious grounds on social media.” The blogger was accused of spreading anti-government propaganda and discriminatory material on social media, as well as publishing materials that made “false claims” of discrimination against the Talysh ethnic group.

KAZAKHSTAN

AUTHOR OF THE REPORT: INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR PROTECTION OF FREEDOM OF SPEECH

PHOTO: MADINA ALIMHANOVA, TELEGRAPH AGENCY KazTAG

1/ KEY FINDINGS

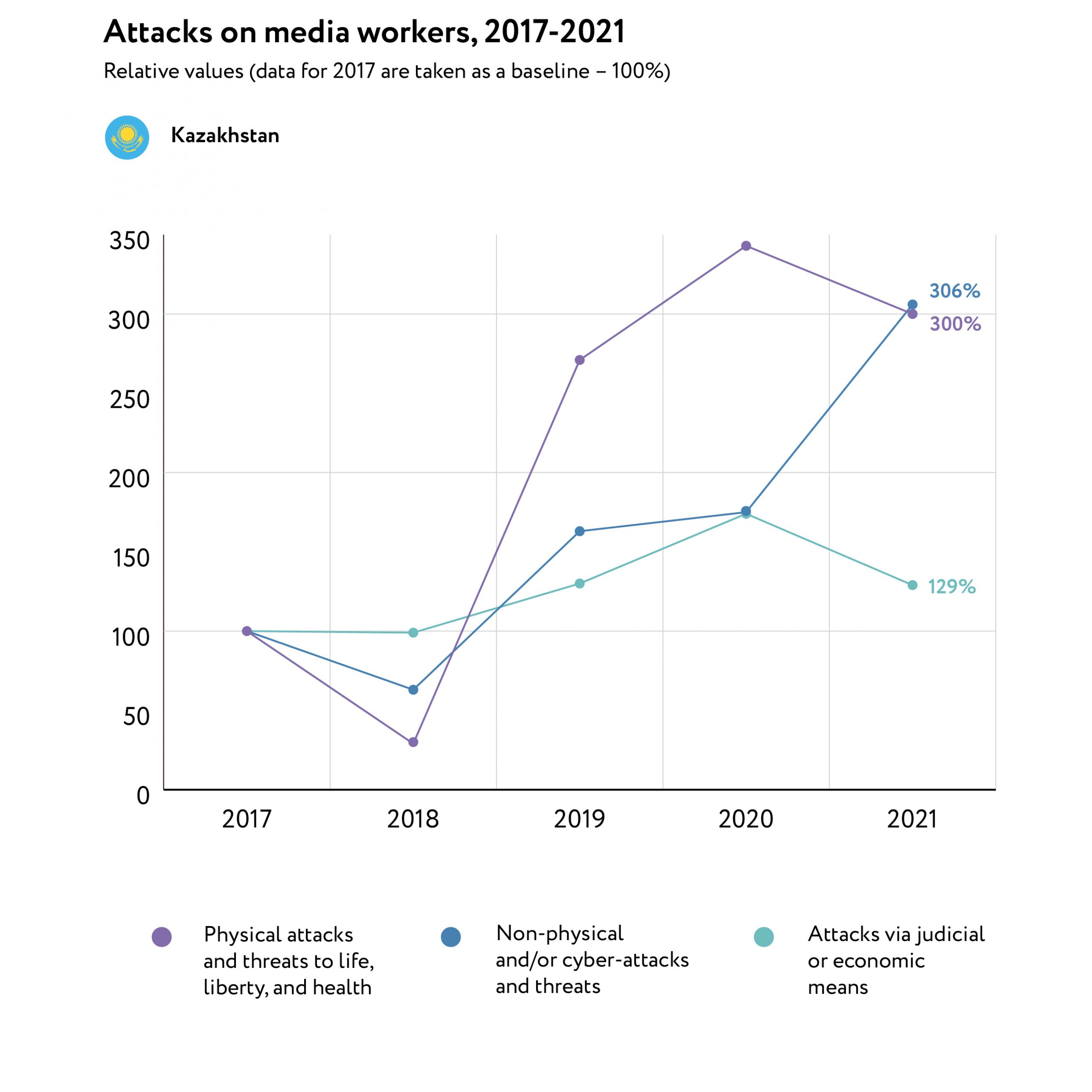

In Kazakhstan, 314 incidents of attacks/threats against media professionals and citizen journalists, editorial offices of traditional and online publications, and online activists were identified and analysed in the course of the research for 2021. Data for the study were collected using open source content analysis in Russian, Kazakh and English. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 3.

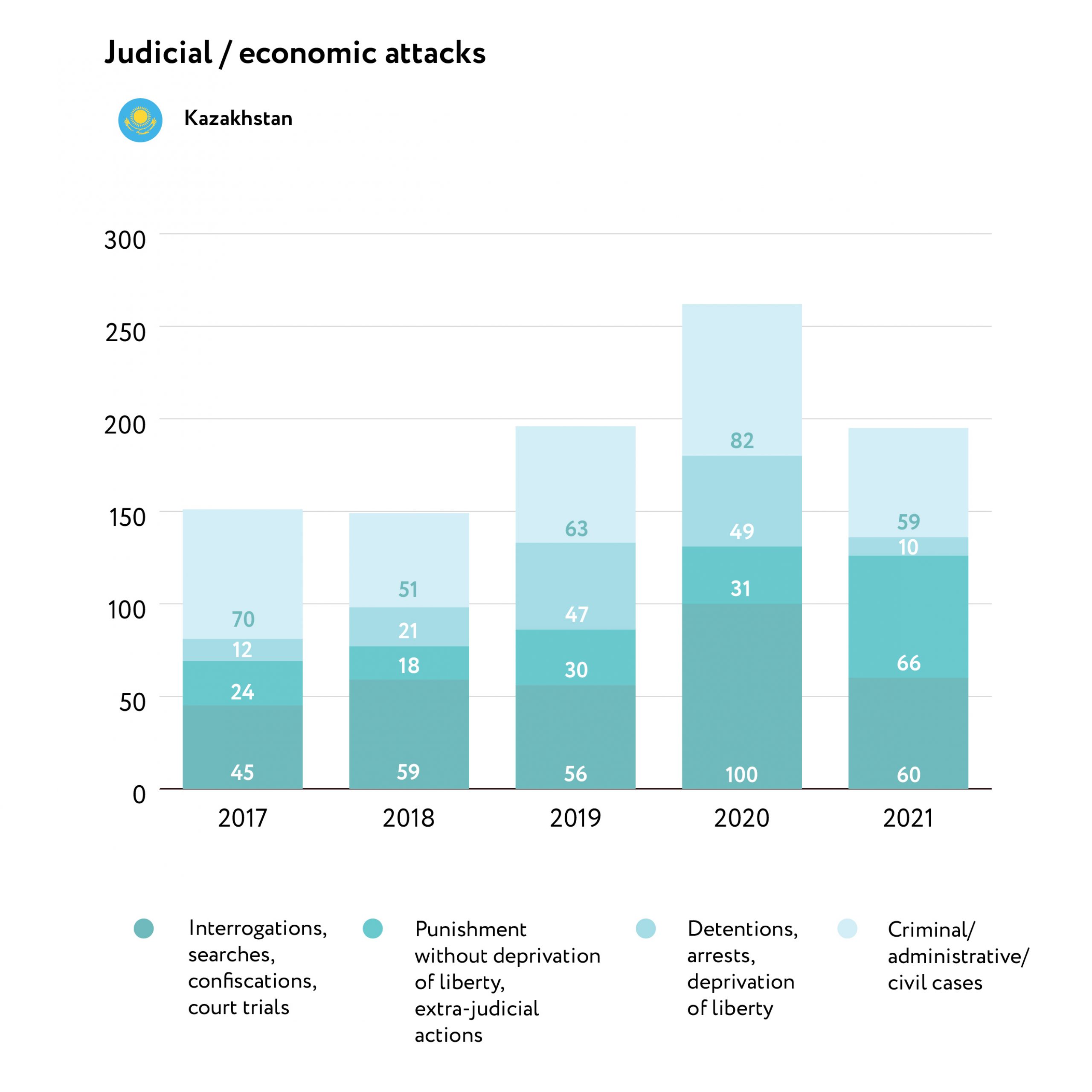

- For the last five years, attacks via judicial and/or economic means (of which there were 195 in 2021) have remained the main method of exerting pressure on media workers in Kazakhstan.

- The most common methods of exerting legal and/or economic pressure on media workers were: litigation (50 incidents), persecution for insults to honour and dignity, damage to reputation, violation of privacy (34 incidents) as well as warnings, pre-trial claims, conversations, questioning and other non-procedural actions (28 incidents).

- The main perpetrators of threats to media workers, bloggers, and online activists in Kazakhstan during this period were government officials (56%).

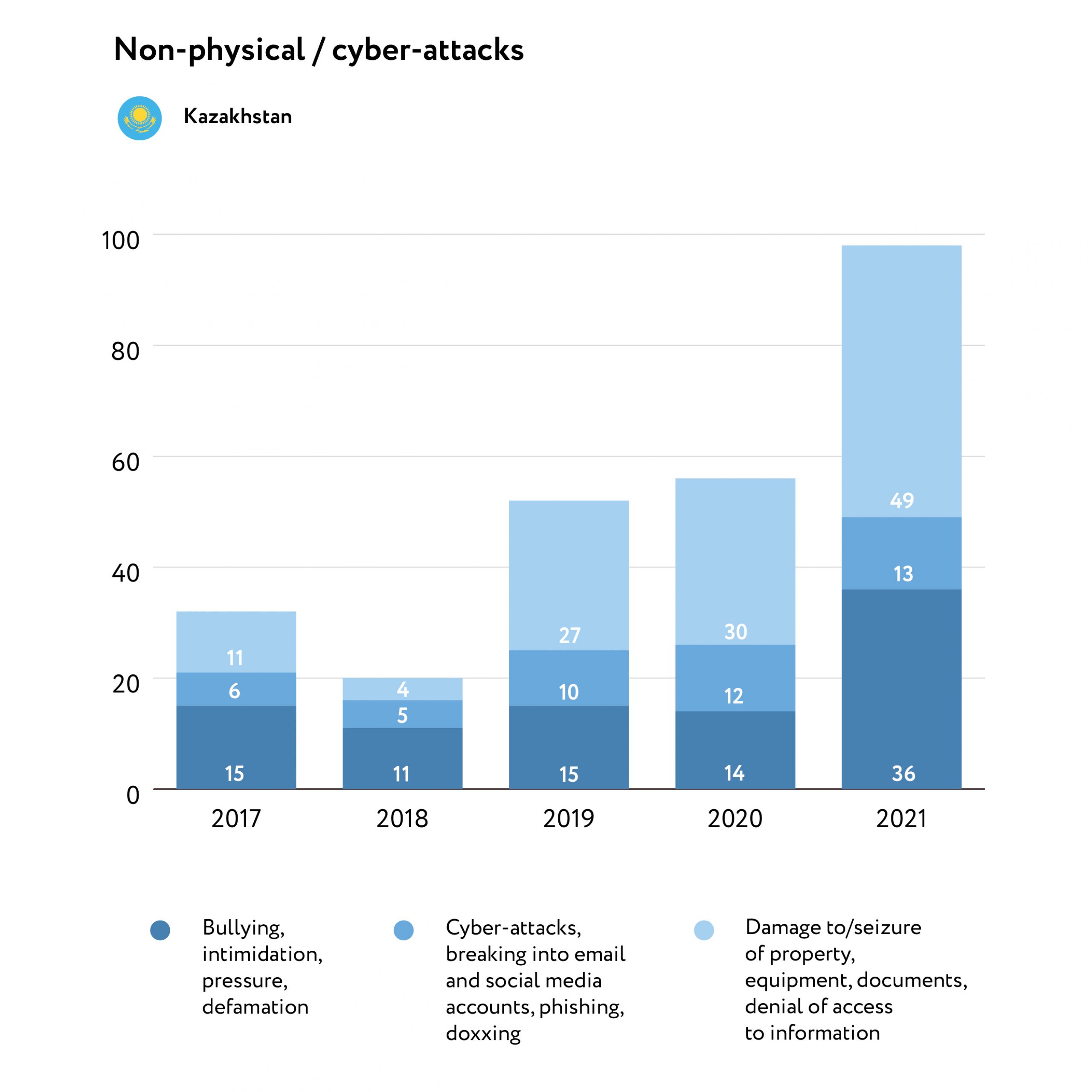

- Attacks and threats of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks were the second most common method of exerting pressure on journalists. The number of such attacks has tripled since 2017. In 54% of cases, these threats came from government officials.

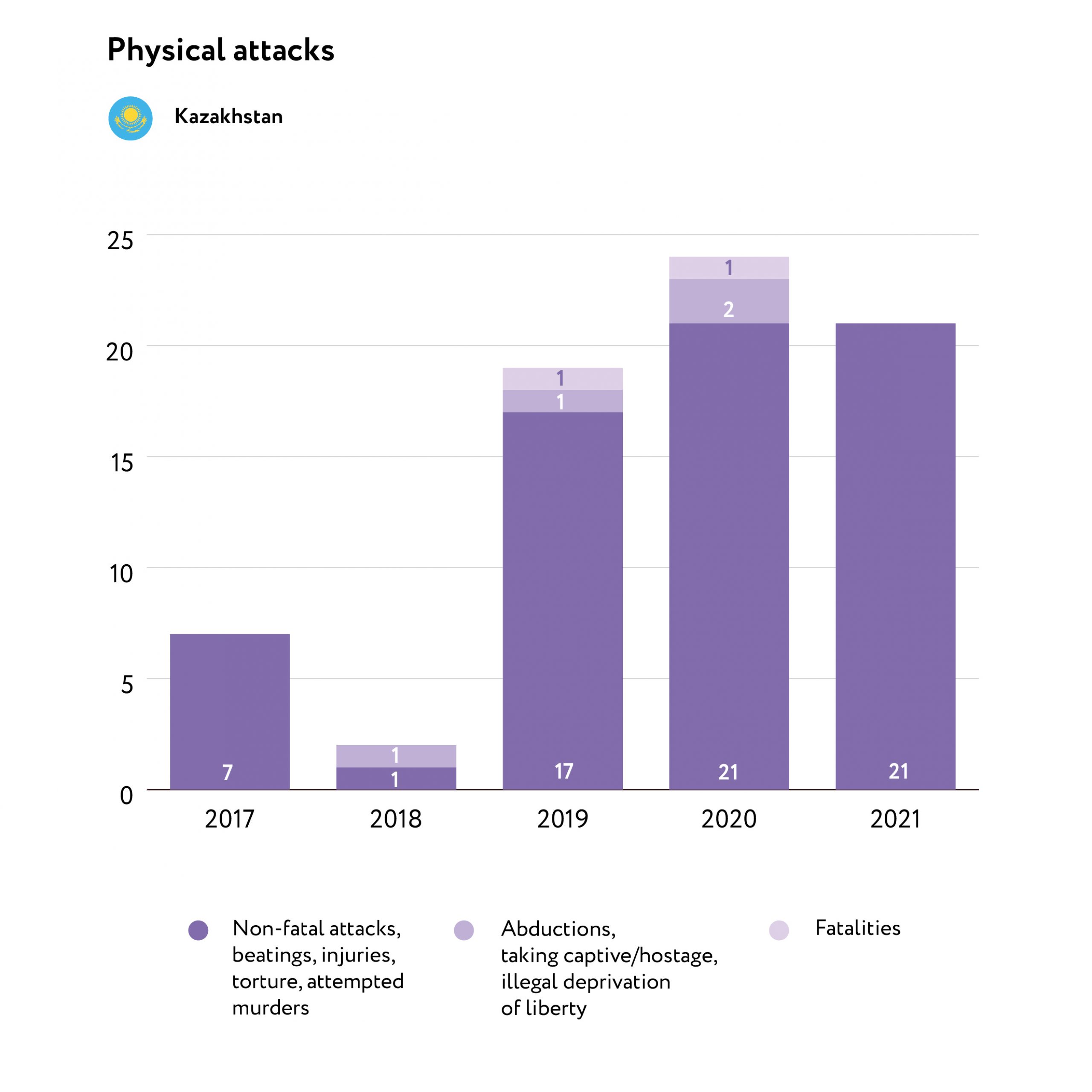

- In 2021, 21 cases of physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health of media workers were recorded. All of these cases involved non-fatal attacks, beatings, injuries or torture. In 95% of cases, journalists were attacked while carrying out their professional duties.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN KAZAKHSTAN

In the latest Reporters Without Borders “World Press Freedom Index 2022″, Kazakhstan’s position significantly improved, ranking 122 out of 180 (in 2021, the country ranked 155th). According to the NGO, “while the quality of online news is improving, repression is modernising, with growing control of the internet, which is the only space where an independent press is granted freedom of expression.”

According to the Freedom House report “Freedom on the Net 2021: The Global Drive to Control Big Tech” Kazakhstan has marginally improved its position, receiving 33 points out of 100 on their internet freedom indicator (having received 32/100 in 2020). The country is therefore still categorised as having a “Not Free” internet.

According to the Ministry of Information and Social Development, as of August 5, 2021, 4,873 domestic and foreign media outlets were registered in Kazakhstan (4,606 domestic and 267 foreign). 3,541 of these are printed media, 184 are television channels, 79 are radio stations, and 802 are news agencies and online publications.

ELECTIONS TO THE LOWER HOUSE OF PARLIAMENT: REGULATIONS AND THE POSITION OF THE MEDIA

On January 10, 2021, two days before the parliamentary and local elections, the Ministry of Information and Public Development published “Recommendations for the media on the Day of Silence and on Election Day.” Here, the Ministry included a reminder about the ban on any election campaigning and recommended “closing comments sections under existing online resources or carrying out moderation to prevent the posting of any comments with calls to vote for a particular political party. Publishing materials about the professional activities of candidates from political parties without indicating their party affiliation, however, is permitted.

Only the media are permitted to cover the elections and broadcast news about the elections. The Central Election Commission recommended that election observers “avoid making any public comments and refuse interview requests.”

Prior to the parliamentary elections, pressure against independent observers and activists increased. Civil activists were arrested on charges of calling for illegal protests or for being involved in banned organisations. Several human rights organisations received multimillion-dollar fines from the tax authorities and were forced to suspend their activities for three months.

During the electoral period (and on the January 10 election day), the list of election observers was strictly limited, and independent journalists were obstructed.

Despite the fact that the requirement for mandatory PCR testing for journalists covering elections was only introduced on June 25 (and was only for those covering the elections of village “akims”, on election day, members of election commissions refused access to journalists or removed them from polling stations. Quarantine restrictions and the absence of a negative PCR test were cited as reasons for this.

The resolution adopted by the European Parliament on February 11 “On the human rights situation in Kazakhstan” highlighted that: “Systemic shortcomings regarding respect for freedom of association, assembly and expression continue to hamper the political landscape, and the absence of genuine political competition and opposition groups (no new parties have been registered since 2013) has left voters with no real choice.” They also noted that “All major opposition national newspapers were banned in 2016, and independent journalists continue to face harassment.”

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC AND MEDIA SITUATION

In 2021, COVID-19 quarantine restrictions of varying severity continued in Kazakhstan.

A ban (introduced on March 16, 2020) on recording of any kind in hospitals, ambulances, quarantine rooms, during medical assitance at home, during an epidemiological investigation, or during interviews and questioning of patients and “contacts,” was valid until September 20, 2021.

Meetings of state bodies were held remotely. Live broadcasts of meetings were disrupted in some cases. Journalists were required to send their questions in advance and often faced difficulties in submitting them. At briefings and press conferences, moderators only presented speakers with the more “convenient” questions.

In April, journalists addressed the President of Kazakhstan with an open letter regarding the problems relating to access to information, exacerbated by the pandemic and quarantine restrictions. The authors of the appeal state that officials used these restrictions as an excuse to sequester themselves from the press.

On September 29, the Central Communications Service (CCS) under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan announced the return of “in-person” press events. No more than 15 people were allowed in the press centre, including journalists and videographers. The list of journalists was chosen by the CCS. For each event, the first 15 people who apply via the WhatsApp chat “OҚҚ/CCS Briefing” are given accreditation. Questions can be asked in-person, and online via ZOOM: The CCS monitors the observance of the order according to the requests in the chat.

On July 1, a clause was introduced by the Chief State Sanitary Doctor of Kazakhstan to restrict workers who have not received their COVID-19 vaccination from entering full-time work. Mandatory weekly PCR testing was introduced for unvaccinated employees of these organisations. The list of organisations includes communications and telecommunications providers, as well as media editorial offices.

LEGISLATIVE REGULATION OF THE MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS’ ACTIVITIES

In 2021, several draft amendments to laws were submitted, which would (if adopted) allow for significant restrictions on the work of the media and journalists to be introduced.

On September 15, the lower house of parliament approved a high-profile bill: “On Amendments and Additions to Certain Legislative Acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan on the Protection of the Rights of the Child.” The draft law, initiated by deputies from the ruling Nur Otan party, contained a number of rules that restricted access to foreign internet sites, social networks, and messaging platforms, if the owners of these sites did not register, or open offices in, Kazakhstan. The head of the representative office (who must be a citizen of Kazakhstan) must, within 24 hours, comply with the instructions of the authorised body regarding cyberbullying against children, and take steps to remove or limit the dissemination of this information.

This draft amendment was roundly criticised by human rights activists, journalists and other civil society advocates: “We are convinced that this approach is ineffective, and the tactics of introducing amendments, under the pretext of protecting the childrens’ rights, is manipulative.”

According to human rights activists, there are now only 12 countries in the world in which the authorities block instant messengers and social networks. These countries can hardly be classified as developed and are at the extreme lower end of the freedom of speech ratings.

In April, the Ministry of Digital Development, Innovation and Aerospace Industry published a draft law for consideration, in which, among other things, it proposed the introduction of a “right to be forgotten.” If an “individual or his legal representative applies, the owner of the online resource is obliged to remove outdated or irrelevant personal information about this individual.” What is considered to be information of a “personal nature,” and in what cases it cannot be deleted, was not specified.

Human rights activists opposed its adoption, considering it to be in violation of the constitutional right to seek and receive information, as well as the fact it created an obvious imbalance between private and public interests.

On November 30, the bill was submitted to parliament for discussion without the “right to be forgotten” clause.

On March 11, the Minister of Information and Social Development, Aida Balaeva, approved the new version of the Rules for the Accreditation of Journalists, which were criticised by journalists and human rights activists during its discussion.

These rules would make it possible to deprive a journalist of accreditation with a state body for disseminating supposedly false information which discredited their business reputation. At the same time, it was not specified who would determine whether something was false or discrediting information, or whether this necessitated a court’s intervention.

The concept of a “leader” was also introduced in these new rules. These individuals are responsible for monitoring the observance by topic participants, regulations, as well as public order. How this individual will be chosen is not specified. Fears that the leader appointed by the organiser would become a kind of censor were confirmed in practice.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

Compared to 2020, the number of attacks in 2021 decreased by 8%. The number of physical attacks decreased by 12% and the number of attacks via judicial and/or economic means decreased by 26%. The number of attacks of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks, however, increased by 75%.

Of the 98 recorded incidents of a non-physical nature, 42 pertain to the illegal obstruction of journalistic activities, and/or deprivation of access to information. The second common method was harassment, intimidation, threats of violence and death, including online threats (24 incidents). The primary aim of these threats was to prevent journalists from covering socially significant and pressing topics. Every incidence of pre-trial investigations, which were initiated due to journalists’ statements, was closed “due to the absence of a criminal offense having been comitted.”

In 56% of cases, attacks on media workers were committed by government officials (176 out of 314). In 35% of cases, the attacks were from individuals who were not representatives of the authorities (112 incidents), and in 8% from unknown persons (26 incidents).

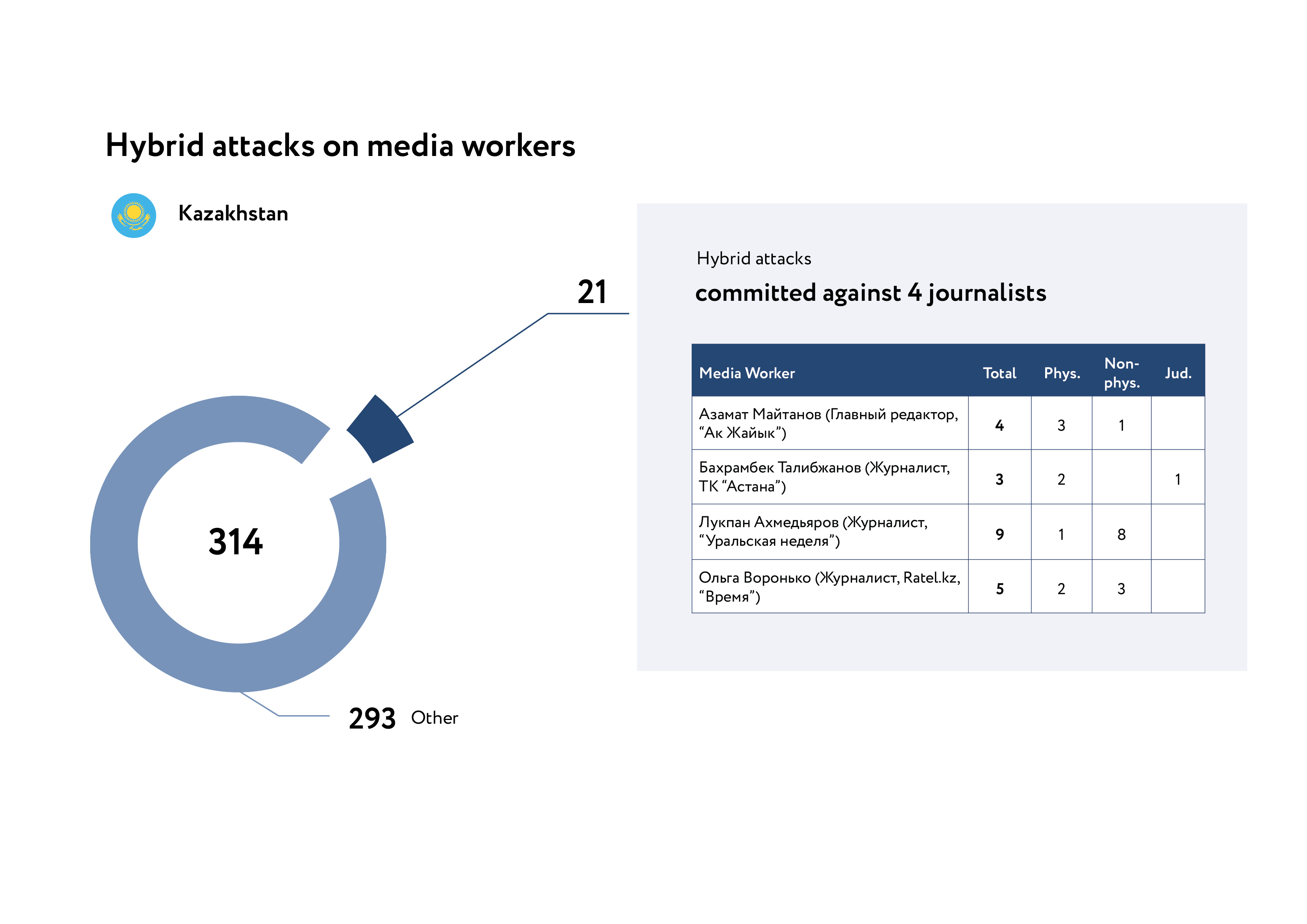

In order to more accurately reflect the combined attacks on media workers, a new category of attacks, “hybrid attacks,” was introduced in 2020.

We are calling systematic persecution of some publication or media worker with the use of tools from two or more categories of assaults – physical, non-physical, and judicial/economic – “hybrid”. Such a combination of means involving and not involving force with judicial means of pressure on undesirable journalists is carried out with a view to demoralising them or getting them to self-censor or to give up the profession or even life itself.

In 2021, 21 hybrid attacks were recorded against four journalists, bloggers, and online activists.

Coronavirus restrictions continue to be used to discourage journalistic activities. In 2021, 15 such incidents were recorded: 12 unlawful obstructions of journalistic activities, 1 non-lethal attack, and 2 criminal/administrative cases:

- On January 10, Nurzhan Iskakov, chairman of the Almaty precinct election commission, acted aggressively towards a Radio Azattyk correspondent. The journalist was pushed out of the polling station, as he allegedly did not have a negative PCR test.

- On July 29, the Almaty Department of Sanitary and Epidemiological Control fined Russian blogger Gusein Gasanov under Article 425 of the Code of Administrative Offenses: violating the “requirements of legislation in the field of sanitary and epidemiological welfare of the population, as well as hygiene standards.” They were fined 87,510 tenge (more than $200). The administrative case stemmed from a meeting with fans in Almaty during quarantine restrictions.

- On July 17, in Almaty, police cordoned off the streets leading to the city’s akimat, where a rally against forced COVID-19 vaccination was to be held. The police refused to let anyone into the city administration building, including journalists. A police officer told Daniyar Musirov and Yuna Korosteleva of the Vlast online magazine, that “the akimat is closed due to quarantine measures.” That same day, security forces stopped journalists nearly every hundred metres to check their documents. There was also no mobile internet signal near the area of the planned rally.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

The number of physical attacks in 2021 tripled compared to 2017, from 7 to 21. In 2021, all incidents of this nature were non-fatal attacks, beatings, injuries, or torture.

In 90% of cases, attacks on journalists were committed while they were carrying out their professional activities. In 10 cases, the perpetrators of the attacks were government officials, in 8 cases the attacks came from individuals who were not representatives of the authorities, and in 3 cases they came from unknown persons.

- Alexandra Sergazinova, editor at the “Tobol-info” news agency, was injured on January 30, while covering a raid by a quarantine compliance monitoring group in Kostanay. A security guard at the Jon Snow karaoke bar forcibly took away the journalist’s mobile phone, which she was using to film. She was pushed out of the building and sustained injuries as a result. The journalist was wearing a vest with the inscription “Press.”

- On March 2, policemen assaulted up Bakhrambek Talibzhanov, a correspondent for the Astana television channel in Shymkent, while covering a fire at an auto parts warehouse. Three police officers restrained Talibzhanov, while another hit the correspondent in the face and stomach.

- Bahrom Abdullaev of Channel 31, was injured by police and had his equipment damaged while covering the detention of protesting jewelry workers in Shymkent on April 4.

- On May 12, a security guard at the Wolt office in Almaty attacked Vyacheslav Timofeev, a videographer for the KTK channel, damaging his camera while he was filming a strike by the company’s couriers.

- On May 27, an unidentified man assaulted 716.kz correspondent Oksana Matasova, while she was filming a piece about child labour.

- On August 2, security at the Dostyk Mall forcibly pushed a film crew from the Khabar television channel – journalists Samat Dzhakupov and Natalya Volkova, and videographer Tolegen Imanov – out of the shopping centre. The journalists were filming a story about a new system to display a person’s COVID status.

- On December 29, Bekbolat Tleukhan, an ex-deputy of the Mazhilis (the lower house of parliament) for the ruling Nur Otan party, attacked Vesti.kg correspondent Ainur Koskina in the parliament building after she asked questions about polygamy. Tleukhan resigned his deputy powers that day. The incident took place in an elevator, where Tleukhan struck Koskina and broke her mobile phone stand.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

In 2021, the number of attacks and threats of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks was almost twice as high as in the previous year (98, up from 56). 75 journalists and media workers, 12 bloggers and 11 online media outlets were subjected to attacks and threats of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks.

Since 2020, the number of incidents related to illegal obstruction of the legitimate professional activities of journalists and bloggers has increased 2.5 times, from 17 to 42. The number of incidents related to harassment, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death (including online threats) has almost doubled, from 14 to 24.

In July, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) published information about the use of cutting-edge Pegasus spyware to wiretap journalists, politicians, and civil activists in more than 10 countries around the world, including Kazakhstan. In their study, OCCRP cites the names of journalists Serikzhan Mauletbai and Bigeldy Gabdullin, as well as online activist and human rights defender Bakhytzhan Toregozhina.

NON-PHYSICAL ATTACKS ON ONLINE MEDIA OUTLETS

Bullying, intimidation, pressure, and threats of violence and death, including online threats (7 incidents), were the main method of non-physical attacks on online media outlets. This pressure was typically used to force editorial offices to remove published materials.

- On January 18, after publishing a piece about a fire in Almaty, editors at Ratel.kz received a letter from M. Sluchenkova, who said she was a marketer for a group of companies located in the office building where the roof had caught fire. Sluchenkova complained and threatening legal action, threatened to spread information that Ratel.kz had received bribes, and demanded that the article be removed from their website.

- On September 1, editors at The Village Kazakhstan reported that they were threatened and received demands to take down a report by journalist Asem Zhapisheva about the life of a boy from Abay and his family, after violence was comitted against them. “We are forced to report that at present our editorial office is being attacked by unidentified persons representing various institutions, insisting that we remove the article. We demand an end to pressure on independent journalists. We do not intend to remove the material,” The Village Kazakhstan wrote in a statement.

- On September 6, editors at Pravo.kz were subjected to pressure following a Facebook post about students at the Taldykorgan Medical College not receiving their stipends. “After publication, we received calls from the college, asking us to remove an individual’s surname. They tried to find out our identities, and then threatened to sue us” claimed the editorial board.

Two cyberattacks were recorded:

- On January 10, the day of elections and protests in Kazakhstan, from 10:00 to 11:30 a.m., the website of the independent online publication Vlast was subject to a DDoS attack.

- From mid-September, the site of the independent media outlet HOLA News Kazakhstan was subjected to several cyberattacks, which the site’s IT service managed to block. As of October 4, the site is unavailable to readers both in Kazakhstan and abroad.

A statement was made on January 10 during the elections to the lower house of parliament, discrediting the independent publication Orda.kz. The head of the Almaty territorial election commission said that Orda.kz’s reports of ballot stuffing during the parliamentary elections were false.

NON-PHYSICAL ATTACKS ON BLOGGERS AND ONLINE ACTIVISTS

In 2021, three incidents were recorded involving the hacking of bloggers and online activists on social networks, as well as one attack related to theft, dissemination of personal data, phishing and doxing:

- On January 10, the day of elections to the Majilis, Askar Shaigumarov, a blogger from Uralsk, reported an attempt to hack his Facebook page.

- On March 16, online activist Baibolat Kunbolatuly reported that his Facebook account and email had been hacked. This took place while he was live streaming a demonstration outside the Chinese consulate in Almaty, where a group of Kazakhs demanded the release of their relatives from Chinese “re-education camps” and prisons. On March 17, Baibolat Kunbolatuly’s WhatsApp account was also hacked. Spam videos were sent from his account.

- On November 24, activists from the unregistered “Oyan, Qazaqstan!” (Wake up, Kazakhstan!) movement received a warning from Apple that their iPhones had been targeted by government-backed hackers. The movement’s Telegram account published the names of these activists, including journalist and activist Asem Zhapisheva and blogger Temirlan Ensebek.

The following incidents were also recorded:

- On May 15, the Qaznews24 Instagram account was closed due to threats received by its admin, Temirlan Ensebek, an activist from “Oyan, Qazaqstan!” The satirical posts in question were on the page for a short time.

- On June 26, video blogger Maxim Ponomarev, who covers the city life of Stepnogorsk on his YouTube channel PMcanal, received threatening calls from unknown individuals, strongly recommending that he not protest the construction of an industrial waste incineration complex.

- On July 25, Mirshat Sarsenbaev, a blogger from the Kostanay region, had his car windshield covered in paint and his tyres slashed. The day before, the blogger had published criticism on VKontakte about the district akim elections.

NON-PHYSICAL ATTACKS ON JOURNALISTS AND MEDIA WORKERS

2021 saw a sharp increase in the number of incidents related to obstruction of the professional activities of journalists (40, up from 27 in 2020). The main perpetrators of the attacks against journalists were government officials (30 out of 40 cases).

The number of such incidents increased during the elections to the lower house of parliament and rural akimats. Journalists were prevented from entering polling stations during voting and were not allowed to be present during vote counting. In all cases, the perpetrators of these incidents were government officials.

- On January 10, the Nur-Sultan Electoral Commission No. 318 chairwoman refused to start counting votes until Radio Azattyk journalist Saniya Toiken had left the premises. Three policemen removed Toiken from the hall and locked the door from the inside.

- On January 10, Yerzhan Bakhytbek, chairman of the Aktobe election commission (No. 28), prevented Radio Azattyk reporter Zhanagul Zhursin from taking photos and videos of members of the election commission. The chairman demanded that “only the ballot box” be included in the footage. Zhursin received permission to take photos and videos after she complained to Gulnara Kunbayeva, chairperson of the Aktobe regional election commission.

12 incidents relating to the non-admission of journalists due to coronavirus restrictions were recorded (5 of which were recorded on January 10).

- On January 10, Radio Azattyk reporter Asylkhan Mamasuly, who covered the elections in the Almaty region, drew attention to the fact that some voters placed more than three vote slips into the ballot box (in some regions, three ballots are given out: for elections to the Mazhilis, the district maslikhat and the regional maslikhat). After that, the chairman of the local electoral committee demanded that the journalist leave the precinct. The fact that the Almaty region is in the “yellow zone” of COVID-19 risk, and journalists can not spend more than 5 minutes at the polling station, was used as justification.

- On January 10, Orda.kz correspondent Saule Sadenova was forbidden from entering a polling station in Almaty on the grounds that she did not have a negative PCR test. At the same time, the decision by the medical authorities does not contain any clauses about journalists needing to have taken tests. Half an hour later, after another reminder of the rules, the journalist was allowed to enter.

Another common method of attack was harassment, intimidation, pressure, violence, and death threats, including online threats. In five cases, these threats came from government officials, in six cases they were from individuals who were not representatives of the authorities, and in four cases they were from unknown persons.

- On January 10, the chairman of the election commission accused Azattyk journalist Sanya Toiken, who filmed the members of the election commission, of breakign the law. They were threatened with legal action and the stripping of their journalistic accreditation.

- On March 27, Timur Gafurov, editor-in-chief of “Nasha Gazeta,” was threatened by an individual going by the name Kairat Akilbaev. The man contacted the publication’s editorial office via WhatsApp to demand that a 2010 article about a lawsuit brought against a police lieutenant following the murder of a disabled person, be removed from their website. At first, the user threatened to take legal action. After the editor refused to delete the article, the user wrote: “The address of the editorial office is on the internet. I am in Zhitikar, I come to Kostanay a lot.”

- On April 4, while covering a protest rally in Shymkent, unidentified individuals threatened to kill Astana TV correspondent Bakhrambek Talibzhanov.

- On June 12, Azamat Maitanov, editor-in-chief of the Ak Zhaiyk newspaper, filed a complaint with the police following a number of threats made against him, as well as the newspaper’s journalists, and his family. These threats to life and health came from an internet user with the nickname Satan, as well as some other accounts.

- On September 1, The Village Kazakhstan journalistAsem Zhapisheva, after publishing a piece entitled: “The Boy from Abay: How the Victims of Violence Live Three Years Later,” was forced to turn off her phone because of threats from unknown individuals.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

In this category, the main methods of exerting pressure on media workers in 2021 were: lawsuits (50), prosecution for insults to honour, dignity, damage to reputation, and violation of privacy (34); warnings, pre-trial claims, questioning, interviews, and other non-procedural actions (28). In 58% of cases, the perpetrators of these attacks were government officials (113 incidents out of 195).

In 2020 attacks in the form of detainment (22), arrests, preliminary detention, and detainment in pre-trial detention centres (16) were widely used. However, in 2021, the number of such cases has fallen to 6 and 2, respectively.

- On February 1, online activist Sholpan Otekeyeva was found guilty of libel and arrested for 20 days by an administrative court for reposting a message on Facebook about the persecution of a civil activist.

- On February 3, Lukpan Akhmedyarov, editor-in-chief of Uralsk Weekly, and deputy editor Raul Uporov, were detained by police. According to Uporov, after Akhmedyarov was pulled over on charges of failing to appear for a police interrogation, but they drove away. After a few kilometres, police caught up with him and demanded that he stop. The driver was informed that he was suspected of involvement in an accident in Uralsk, as his car matched the description of the vehicle in question. After that, he escorted to the village of Chapaevo to give testimony.

- On July 27, Nur-Sultan police officers detained the editor-in-chief of Uralsk Weekly, Lukpan Akhmedyarov, and videographer Isatai Duisekeshov. They had filmed a panorama of the city using a drone. Police demanded that the journalists produce evidence that they had permission to fly a drone in the area. The police themselves, however, could not specify which authority was responsible for issuing such permits.

CRIMINAL/ADMINISTRATIVE CASES AND PROSECUTION FOR VIOLATIONS OF PRIVACY, AND INSULTS TO HONOR, DIGNITY AND REPUTATION

In 2021, 59 attacks relating to the initiation of criminal and administrative cases were recorded, as well as the civil prosecution of journalists. In 30 of these cases, the attacks were perpetrated by government officials.

- One particularly resonant example of this was the civil lawsuit (for the protection of honour, dignity, and business reputation) initiated by Bauyrzhan Baybek, the first deputy chairman of the ruling Nur Otan party and ex-mayor of Almaty; against blogger and political activist Zhanbolat Mamai and his wife, journalist Inge Imanbai. The basis for the lawsuit was Mamai’s investigative film “Bauyrzhan Baybek: the corrupt business empire of the son of Nazarbayev’s classmate,” which was published on YouTube. On June 15, the court ordered the defendants to remove the film from social media and cover Baybek’s legal expenses. The decision was partially carried out – Baybek was paid for his legal expenses. Mamai and Imanbai refused to take down the film and were fined for non-compliance with a court decision.

- On August 19, blogger Yermek Taychibekov was sentenced to seven years in prison. He was found guilty of inciting ethnic hatred via the media. The blogger pleaded not guilty. Taychibekov was detained in September 2020, allegedly because of an interview in which he criticised the Kazakh authorities’ national policy.

- On April 29, a court sentenced blogger and journalist Aigul Utepova to a year of restricted movement and 100 hours of forced labour on charges of participating in the activities of a banned organisation. Utepova was banned from engaging in public and political activities for three years, including working in the media and telecommunications. The prosecution claimed that Utepova posted material on social media in support of the “Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan” and “Köşe Partiasy” movements, which were recognised by the Kazakh court as “extremist,” but are considered to be peaceful opposition organisations by the European Parliament. Aigul Utepova denies the allegations.

- On June 29, police officer Artem Stolyarchuk filed a lawsuit against SAPMAR LLP (the Ratel.kz analytical portal) and Ratel.kz correspondent Dmitry Matveev in a civil court, citing damages to their honour, dignity, and business reputation. The plaintiff demanded that the information in Matveev’s article be recognised as untrue and libellous, and that the defendants be made to issue a retraction and pay 2 million tenge (4,200 USD) in compensation for moral damage. On June 29, the court partially fulfilled these demands, recognising that the title of the publication and subsequent claims that Stolyarchuk was sent to a pre-trial detention centre were untrue and discredited his honour and dignity. The defendants were instructed by the court to publish a retraction, reimburse Stolyarchuk 140,000 tenge in compensation, plus a further 150,000 tenge to cover legal expenses, and pay their own state fee.

Litigation took place on the following charges:

- Organising and participating in an illegal protest

On June 22, Boybolat Kunbolatuly, an online activist fighting for the release of his brother, who has been imprisoned for several years in Xinjiang, China, was arrested for 15 days. The court found Boybolat guilty of “organising an illegal demonstration in front of the Chinese consulate.” Boybolat stated in court that he did not organise it, and that he was merely a blogger sharing information about the protests. On June 25, the Court of Appeals reduced the sentence to seven days.

- Media defamation

On February 17, by an administrative court ruling, blogger, and online activist Aigul Akberdy was fined 525,060 tenge (more than $1,200) on charges of defamation (Article 73-3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses). The accusation was based on reposted messages on Facebook from the “Blacklist of the Dishonest” page, detailing the persecution of a civil activist by the police. The administrative case against Akberdy was initiated at the request of the colonel of the Beyneu police department.

- Disobeying police

On May 19, blogger Dauren Ukin, who publishes videos on the Azattyk Alany YouTube channel, was subjected to a judicial administrative punishment, in the form of a warning, for disobeying the lawful demands of a police officer. According to investigators, Ukin filmed a video on his mobile phone in the entrance of the police station, and then resumed filming in the office of the deputy head of the police station. He ignored demands from the police to stop filming.

- Violation of the rules for the protection of plant and animal habitats

On January 21, by a court ruling, blogger Azamat Sarsenbaev was found guilty of violating “the rules for protecting plant and animal habitats, as well as the rules for creating, storing, recording and using zoological collections, illegal resettlement, introduction, reintroduction and hybridisation of animal species.” As punishment, an administrative penalty in the form of a warning was given. This stemmed from a drone video, taken by Sarsenbaev, of pink flamingos on Lake Karakol.

Warnings, pre-trial claims, questioning, interviews, and other non-procedural actions (28 incidents) were comitted by representatives of the authorities in 16 cases:

- On July 28, a member of the lower house of parliament, Zhanat Omarbekova, brought a pre-trial claim against the Newtimes.kz news agency and Channel 7. Omarbekova demanded that a retraction be published and the article “Mazhilisman’s daughter-in-law lives in a crisis centre awaiting alimony” from the news agency’s online portal be removed, both from their channel and other sources (Facebook and Instagram).

- On November 8, the deputy akim of the Atyrau region, Kairat Nurlybaev, contacted the Atyrau police department with a pre-trial claim. He demanded that Ak Zhaiyk correspondent Farhat Abilov and editor-in-chief Azamat Maitanov be prosecuted for violations of privacy and personal data protection laws. This stemmed from the publication of a piece claiming that the deputy akim was a defendant in a criminal case under related to the “Assignment or embezzlement of others’ property.” Nurlybaev later withdrew the application.

Other incidents:

- On August 3, the Semey City Court, in the East Kazakhstan Region, issued a decision to deport Russian citizen Serik Ualikhanov, the head of the Alpha Marino media centre, who held a residence permit in Kazakhstan. The Semey Police Department filed an expulsion application to the court, claiming that Ualikhanov had been prosecuted more than six times (once in October 2020 and five times on July 2, 2021). According to the court decision, Ualikhanov must leave Kazakhstan within 10 days. According to the “Law on the Legal Status of Foreigners,” he was prohibited from entering the country for five years after his expulsion.

- On October 15, the founders of HOLA News Kazakhstan, Alisher Kaidarov, Adilet Tursynbekov and editor-in-chief Zarina Akhmatova announced that they were leaving the project. “Circumstances have developed in such a way that, after being blocked for 10 days, we had to give up our basic principles [of honesty and objectivity]. We have removed the article from the site. […] That is why we believe that, in order to remain yourself, leaving is better than staying,” they wrote, in an appeal to readers. The deleted article discussed the “Pandora Papers” and the involvement of more than 35 world leaders and 400 officials from numerous countries (including Kazakhstan) in offshore finance schemes.

KYRGYZSTAN

AUTHOR OF THE REPORT: SCHOOL OF PEACEMAKING AND MEDIA TECHNOLOGY IN CENTRAL ASIA

PHOTO: AIBOL KOZHOMURATOV’S TWITTER ACCOUNT

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Kyrgyzstan, 39 cases of attacks/threats against professional and citizen media workers, and editorial offices of traditional and online publications, were identified and analysed in the course of the research for 2021. Data for the study were collected using open-source content analysis in Kyrgyz, Russian and English. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 4.

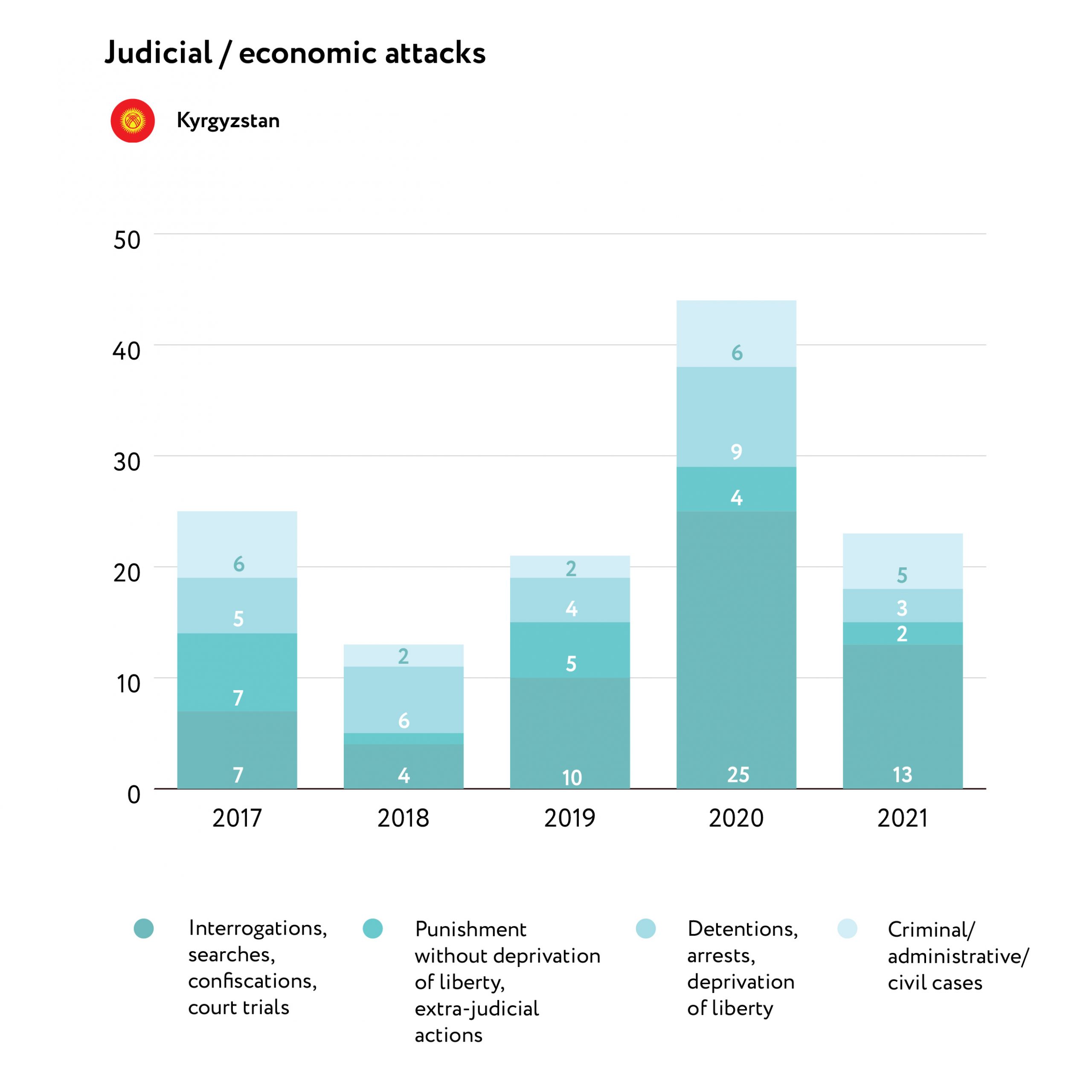

- The main method of exerting pressure on media workers, as was the case in the previous year, was judicial and/or economic means.

- 69 percent of the attacks on media workers and organisations were perpetrated by representatives of the authorities.

- The greatest number of attacks was recorded in April 2021, when a referendum on Constitutional amendments and elections to local authorities were held in Kyrgyzstan.

- The kidnapping of independent journalist Ulukbek Karybek uulu during the Prime Minister’s visit to the Issyk-Kul region was a particularly egregious case.

- In 2021, experts noted a deterioration in access to information, as well as an increase in self-censorship and increasing restrictions on freedom of speech.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN KYRGYZSTAN

In Reporters Without Borders’ annual Press Freedom Index, Kyrgyzstan moved up three places in 2021 to 79th out of 180 countries. Kyrgyzstan was ranked 82nd in 2020, 83rd in 2019, and 98th in 2018.

According to the annual Freedom in the World report by Freedom House, the country’s rating decreased from 39 points in 2020, to 28 in 2021. For the first time in 11 years, Kyrgyzstan was included in the category of “not free” countries.

In 2021, the socio-political situation in the country was influenced by four electoral events. Human rights activists noted the persecution of those who criticised the new authorities’ policies, plus infringements on freedom of speech and increased pressure on the media during the early presidential, parliamentary, and local elections, as well as the referendum on Constitutional amendments. On the eve of the presidential elections, the Resistance to Political Repressions Committee created in Kyrgyzstan by the civil activist and former member of the SDPK political party, Adil Turdukulov, released a statement about increasing pressure on the media.

These elections contributed to the growth of media activity. In 2021, 224 media outlets operated in the country: 77 online publications, 60 television channels, 60 newspapers and 27 radio stations.

Despite the increase in the number of media outlets, the diversity of opinion expressed through the media became narrower. In 2021, against the backdrop of a political upheaval, coverage of the electoral process was extremely restrained compared to 2020, with minimal alternative and independent information sources and available to voters.

This was the result of increased censorship, including self-censorship, a general deterioration of human rights and freedom of speech, the adoption of the law “On the protection from false and unreliable information”, as well as a decrease in online freedom of expression, and other negative factors affecting media freedom.

In April 2021, after adopting the new Constitution of the Kyrgyz Republic, the authorities quickly revised 359 laws, despite objections from independent experts and journalists. Amongst these were the laws “On the Media,” “On the Protection of the Professional Activities of a Journalist,” “On Television and Radio Broadcasting,” and “On Public Broadcasting Corporation.” These amendments, among other things, returned the Public Broadcasting Corporation to state ownership, and stated that its head will be appointed by the President.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

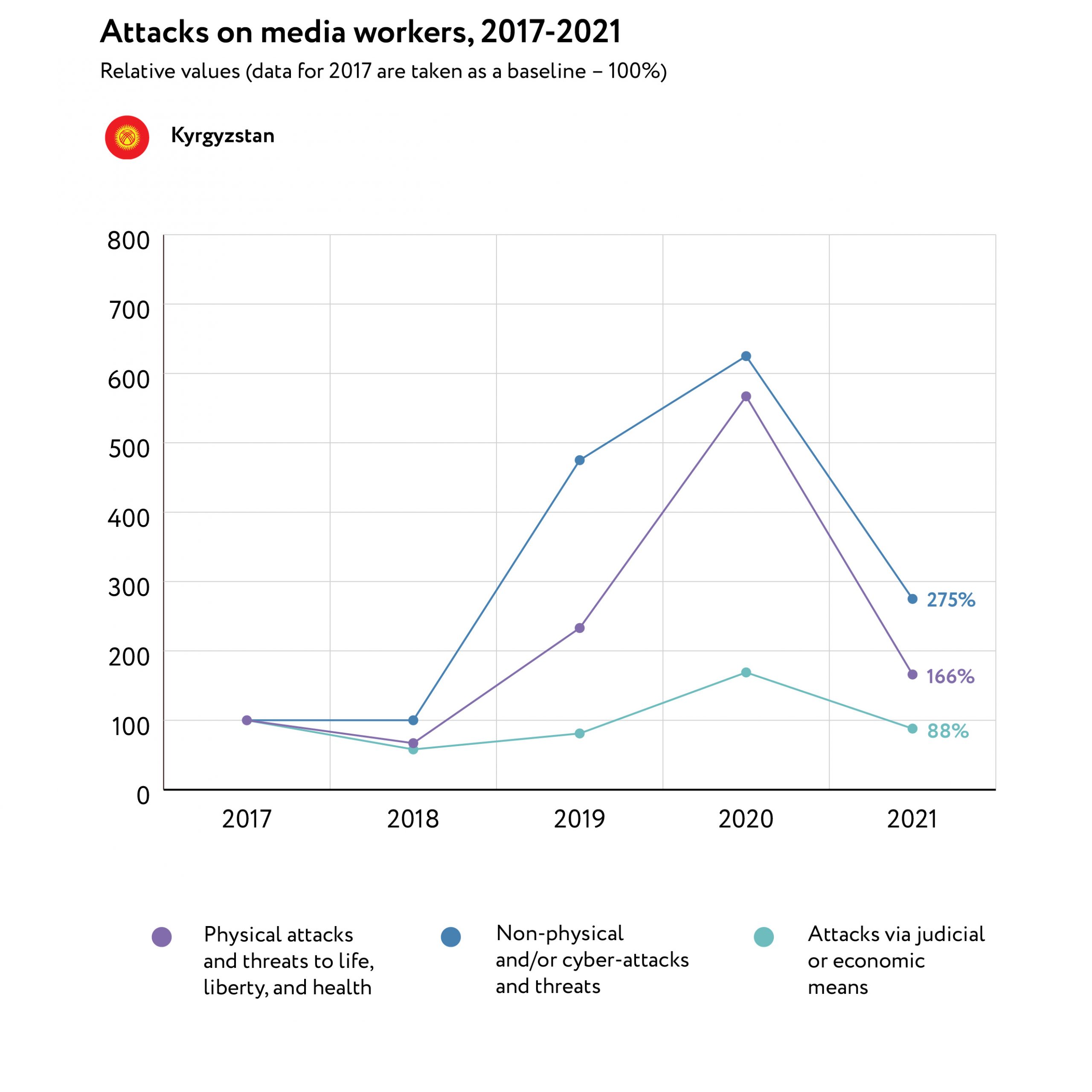

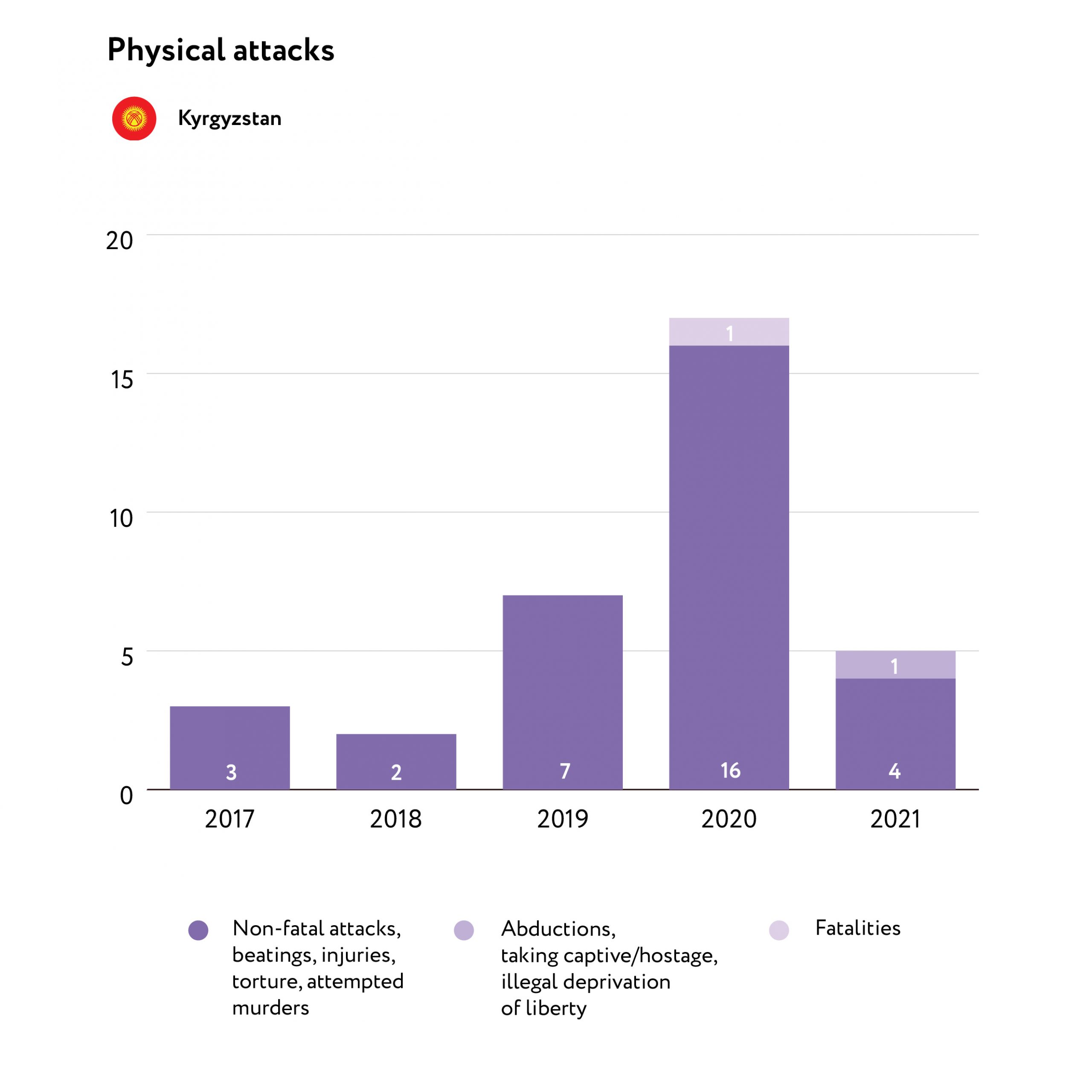

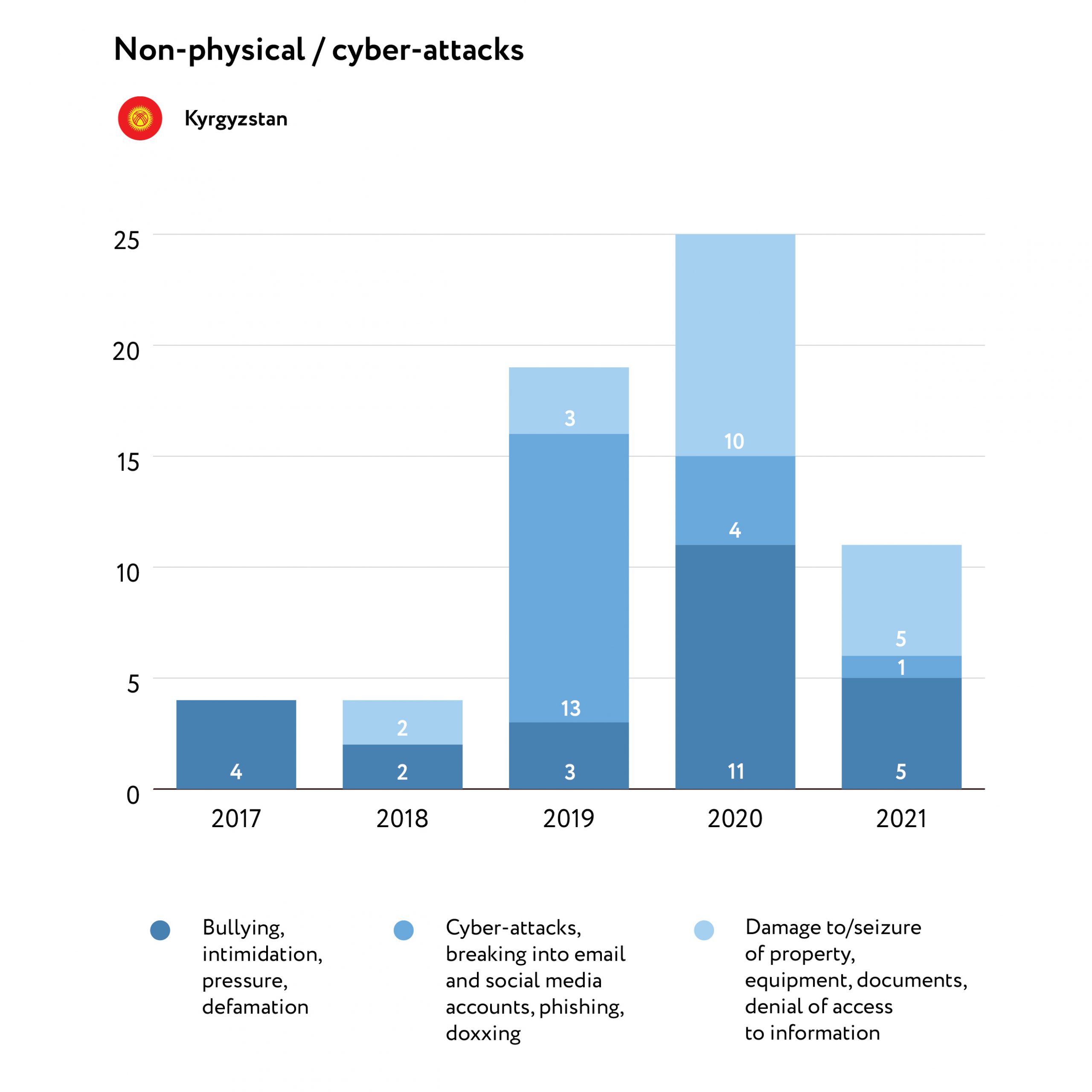

In 2021, 39 attacks/threats were recorded against journalists, bloggers, media workers and editorial offices of traditional and online publications. This is two times fewer than in 2020, when the main risks for the media were associated with political instability and revolutionary events.

In 2020, the largest number of incidents were recorded during the coverage of protests and the dispersal of demonstrators. Despite the decrease in the number of documented attacks, many media workers in Kyrgyzstan complained of psychological burnout.

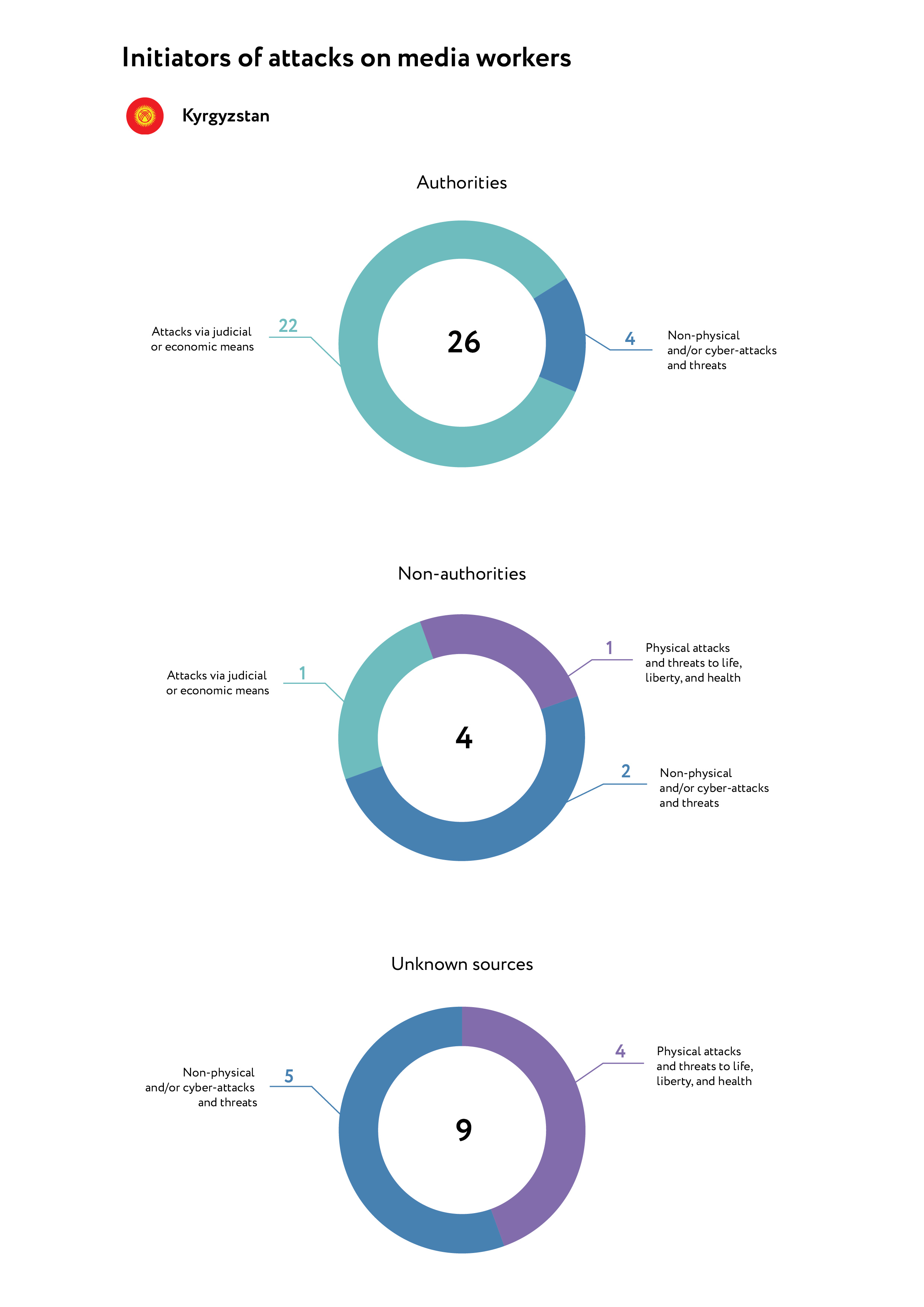

In 2021, 26 of the 39 recorded attacks came from representatives of the authorities, 13 – from non-authorities and unknown sources.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

In 2021, five cases of physical attacks on journalists were recorded. Four incidents were non-fatal physical attacks, while one involved kidnapping/illegal deprivation of liberty.

- On April 11, Kloop.kg correspondents Alyima Alymova and Bekmyrza Isakov were broadcasting live, reporting on electoral violations during the elections and the Constitution referendum. They were attacked at a polling station by a group of women, who assaulted the journalists and seized their phones.

- On April 30, Zulfiya Turgunova, a regional correspondent for the news agency “Sputnik Kyrgyzstan,” was attacked. She was covering a meeting between residents of the Batken region with the chairperson of the State Committee for National Security (SCNS) of the Kyrgyz Republic, Kamchybek Tashiev, where the issue of disputed border areas was being discussed. Unknown individuals prevented Turgunova from filming, then knocked her to the ground and began to drag her away. The incident took place in the presence of SCNS security officers and local governor, who did not intervene into the conflict.

- On August 6, independent journalist Ulukbek Karybek uulu was abducted by unknown individuals in the Jeti-Ögüz district of the Issyk-Kul region. This took place around the time of a meeting between Prime Minister Ulukbek Maripov and local residents who had been affected by flooding. The journalist recorded several videos commenting on local issues and criticising Maripov. Three aggressive men approached him and demanded that the journalist leave the area. When he refused, he was dragged into a car and taken away in the direction of Karakol, a city in the region. At one point, the car stopped, and the journalist managed to escape from the kidnappers.

- On November 28, OshTV journalistAbdumalik Bazarbayev was covering the parliamentary elections near a polling station in the city of Osh, when a man ran up to him, began to both physically and verbally attack him, and demanded that he stop filming. As the media later reported, the attacker turned out to be a representative of Aibek Osmonov, a candidate in the Osh single-mandate constituency № 7.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

Compared to 2020, the number of attacks associated with harassment, intimidation and slander fell by more than half, from 11 to five. The number of incidents related to the damage and seizure of property, equipment and materials, as well as deprivation of access to information also halved, from ten to five. Only one cyber-attack was recorded.

- On April 19, investigative journalist Bolot Temirov, creator of the Temirov Live KG YouTube channel, started receiving threats on social media. Attempts were also made to hack Temirov’s Facebook and Instagram accounts. The journalist was told that “they would come for him” if he did not remove his report on protesters demanding the resignation of the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ulan Niyazbekov. Temirov wrote that provocateurs at the rally were following instructions from plain-clothes police officers. Investigative journalists from the Temirov Live KG YouTube channel were able to identify several examples of these individuals.

In 2021, four non-physical attacks by government officials were recorded; two attacks were perpetrated by individuals who were not representatives of the authorities, and five were by unknown individuals. All threats were related to journalistic activities, and the main aim of the attackers was to silence media workers.

Non-physical attacks by government officials:

- On January 19, Shaista Shatmanova, host of the Political Cocktail program on SuperTV, received a threatening phone call: she was told to “not bring up the issue” of Raimbek Matraimov, a former deputy of the State Customs Service. Matraimov was investigated a number of times by journalists in relation to corruption and organised crime and was included by the United States on the so-called “Magnitsky list” of sanctioned individuals. The call came after the acting President, Talant Mamytov, was sent a list of questions that would be asked on air.

- On February 3, employees of the SCNS searched the home of Yulia Baranina, the admin of the Pravdorub.kg Facebook page, and confiscated her electronic devices, personal documents, and money. According to the warrant, the search was carried out as a result of provocative statements “aimed at inciting ethnic and regional hatred, as well as content inciting violence.” Baranina had previously reported that she was under surveillance and her phones had been wiretapped.

- Late at night on April 19, a group of police officers came to the house of April TV journalist Kanat Kanimetov’s relatives, in the town of Balykchy. The journalist lives and works in Bishkek. His relatives were told that “a command came from their superiours” to establish the whereabouts of Kanimetov, as he had allegedly ignored a summons for interrogation. “One of the policemen, it turns out, even frightened my family by conducting a search of the house… and forced them to sign some kind of paper stating that I do not live there,”the journalist wrote on social media. According to him, the police also questioned his relatives’ neighbours. The real reason behind these investigative actions is unknown.

- On November 21, the Central Commission for Elections and Referendums issued a directive banning coverage of election-related research in the media and online publications, starting from November 23, 2021. It was on November 23 that the “School of Peacemaking and Media Technology” had planned to publish the results of the second stage of a media monitoring report, as well as recommendations for the media, authorities, political parties, and candidates. The unexpected ban denied audiences access to this report documenting and monitoring hate speech and freedom of expression in Kyrgyzstan’s electoral discourse.

Other non-physical attacks include:

- On February 9, more than 15 people broke into the offices of the TMG TV channel in the city of Osh. A crowd of unknown individuals shouted accusations that the journalists were spreading false information, before demanding explanations. The day before, the channel published investigations about corruption related to the distribution of humanitarian aid during the COVID-19 quarantine period, as well as the illegal sale of land in the Shark region of the Kara-Suu district. According to the channel’s correspondents, they received threats during the previous day’s investigation from, amongst others, the head of the village of Padavan, who suggested that journalists “close the case” and “not broadcast the material.”

- On September 23, Aimak News journalist Abdykerim kyzy Aisezim was subjected to intimidation and threats while visiting a nursing home for the elderly and disabled. During an interview with the director, one of the residents of the home approached the journalist and complained about the poor conditions. She began to record these complaints on her phone. Suddenly, the director grabbed the journalist’s phone and demanded that she not only delete the recordings, but also stay in the nursing home and write positive things about the conditions there. The security guard at the institution tried to prevent the journalist from leaving the building, but the taxi driver hired by the editorial office helped them escape.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

The number of attacks via judicial and/or economic means halved in 2021, compared to 2020. However, this method of exerting pressure remained the most common. All incidents in this category were perpetrated by government officials, with the following exception:

- On November 27, YouTube removed a video from the Kloop.kg channel as it allegedly contained “insults, threats, or intimidation.” According to the channel, this was a Kyrgyz language instructional video for Kloop.kg observers who were covering the elections in Kyrgyzstan. According to the journalists, this video did not include any insults, threats, or intimidation. “The video was not even publicly available: it was an instructional video that only our observers had access to via a private link,” the editorial office said. “We suspect that those who want to prevent us from effectively observing the upcoming elections organised a huge number of false complaints.” The appeal was dismissed, and the video was removed two days before the parliamentary elections. YouTube banned Kloop.kg from publishing any content on the channel for a week.

In 2021, two arrests of media workers were recorded.

- On October 28, blogger Gulzat Alymkulova, known online as Gulzat Mamytbek, was detained upon arrival in Kyrgyzstan from Turkey, as part of pre-trial proceedings under Article 204 (“Fraud”) of the Criminal Code. She was taken from the airport to a pre-trial detention centre, where she was held for a month. According to the Main Department of Internal Affairs of Bishkek, seven individuals accused Alymkulova of fraud in 2020.