AUTHOR OF THE REPORT: THE INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR FREEDOM OF SPEECH PROTECTION

PHOTO: MADINA ALIMHANOVA, JOURNALIST

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Kazakhstan, 347 attacks/threats against professional and citizen media workers, activists, editorial offices of traditional and online media outlets were identified and analysed in the course of the study for 2024. Data for the study were collected using content analysis from open sources in Kazakh, Russian and English; and were based on reports by correspondents from “Adil Soz” (the International Foundation for the Defence of Freedom of Speech). A list of the main sources is provided in Annex 1.

- Attacks via judicial and/or economic means remained the main method of exerting pressure against media workers, bloggers and online activists (218 cases, 62% of the total). The most common methods were extrajudicial and judicial activities, summons for interviews and interrogations and charges in criminal and administrative cases.

- 55% of such incidents (119 cases) were perpetrated by individuals and organisations not related to the state structures. 42% of the arracks (91 case) were carried out by representatives of the authorities.

- In 2024, 125 attacks of a non-physical nature were recorded, including cyber threats and online pressure.

- Four cases of physical attacks and threats to the life, liberty and health of media workers were also recorded in 2024. This is one of the lowest rates since monitoring began in 2017.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN KAZAKHSTAN

Freedom of speech in Kazakhstan remains under threat. The country continues to be ranked low down on the lists of various international organisations, and still has the status of a country that is “not free”. In 2024, in the annual World Press Freedom Index, published by the NGO, Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Kazakhstan dropped eight places compared to 2023 and is now 142nd out of 180 countries. The report notes the limited number of independent media outlets in the country and the increased level of state control over the Internet, the only space where alternative information can be published.

In the “Freedom in the World” report compiled by Freedom House, Kazakhstan scored 23 points out of 100, so is still considered as “not free”. This has been the case for the previous five years. The authors of the report note that parliamentary and presidential elections in Kazakhstan do not meet the required standards of freedom and fairness. Most of the mainstream media are either state-controlled or owned by businesses loyal to the government. As the report emphasises, freedom of expression and freedom of assembly remain severely restricted.

In another Freedom House report, “Freedom on the Net”, in 2024 Kazakhstan received 34 points out of 100, the same as in the previous period. So the country remains in the category of countries with an Internet deemed “not-free”. Among the main factors that affected the country’s assessment, Freedom House highlights the law, “On Online Platforms and Online Advertising”. This was approved in April by the Majilis (Parliament) as part of the law “On Mass Media”, which empowers the authorities to monitor the mass media, “for harming the moral development of society and the violation of universal, national, cultural and family values”. The country’s assessment was also influenced by cyber-attacks that online media and journalists faced throughout the period under review (June 2023 – May 2024).

According to a study conducted by the non-profit project “the Open Observatory of Network Interference” (OONI), in cooperation with the “Internet Freedom in Kazakhstan” (IFKZ) and the Eurasian Digital Foundation, between June 2023 and June 2024 cases of Internet censorship persisted in Kazakhstan. In its analysis, OONI examined attempts to block news websites, human rights platforms and sites with political content, as well as circumvention sites (such as VPNs and proxy services) that provide tools to bypass censorship. There were 73 circumvention sites blocked in Kazakhstan, as well as 17 news websites, most of which are foreign media. In addition, several human rights platforms were made unavailable, including the petition website, Egov.press, and the Russian language version of the Amnesty International website.

In its report, “Kazakhstan: Background and Issues for Congress”, the U.S. Congressional Research Service touches upon human rights in Kazakhstan. Researchers refer to the report of the U.S. Department of State, which spoke about serious problems in the area of human rights. Key issues include: insufficient independence of the judiciary system; significant restrictions on freedom of speech and the media; restrictions on Internet freedom; and interference with the freedom of peaceful assembly and association.

Examples of pressure on media workers include problems in January 2024 with the accreditation of 36 journalists from Radio Azattyk (resolved only in April); and a law that implies that the dissemination of false information on the Internet will lead to a fine, whilst not providing clarification as to how the veracity of online content should be determined.

According to the Ministry of Culture and Information, as of December 2024 there are 5919 media outlets registered in Kazakhstan, of which 4042 are periodicals, 227 are TV channels, 95 are radio stations, 668 are news agencies, and 585 are online news sites. Of these media outlets, 5617 are domestic and 302 are foreign (primarily TV channels).

In 2024, 506 new media outlets were registered in Kazakhstan, of which 114 are periodicals, five are TV channels, three are radio stations, and 379 news agencies and online publications (189 – news agencies and 185 – online publications). Among these 506 media outlets, 501 are domestic media and five are foreign.

EVENTS IN THE COUNTRY THAT HAVE AFFECTED MEDIA FREEDOM

Coverage of floods

In the spring of 2024, Kazakhstan faced unprecedented floods that affected dozens of settlements in several regions. A state of emergency was declared in ten regions of the country, and an operational headquarters was created at the government level directly coordinated by the head of state. The emergency meant that questions of security, keeping the population informed and respecting the rights of journalists were particularly important.

On 21 April, the Deputy Head of the Department of Emergency Situations of the West Kazakhstan Region, Kanat Karabalayev, announced at a briefing that journalists and bloggers were prohibited from visiting flooded areas and from using drones, citing safety concerns and UAV operating rules. He specified that the press service of the regional Department of Emergency Situations would provide photo and video materials for the media, while citizens and other interested parties in the region could receive updates from the BATYS TODAY information headquarters.

The International Foundation for the Protection of Freedom of Speech, “Adil Soz”, announced that such restrictions are against the law: in accordance with Article 17 of the Law “On State Secrets”, and Article 20 of the Law “On Mass Media”, journalists have the right to cover the consequences of natural disasters. When information is monopolised by government agencies, facts may be distorted and public trust undermined.

In an addresses to citizens, bloggers and the media, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev stressed the need to trust official sources and prevent the spread of unverified information. At a session of the Assembly of the People of Kazakhstan, he called for the consolidation of society, warned against “whipping up hysteria” and noted the importance of interaction between government agencies and civil society.

The Minister of Culture and Information, Aida Balayeva, reported 29 recorded cases of dissemination of false information, concerning threats of dam breaks, the destruction of strategic facilities and evacuation. According to her, fake messages distracted rescue services and complicated work on the ground. The Ministry called on the media and social media users to be responsible and verify information before publication.

Nevertheless, the approach to the coverage of the floods taken by the state and its affiliated media drew criticism from media representatives. Journalist and strategic communications expert, Dana Saudagerova, emphasised that the protests of residents of the city of Kulsary, which suffered as a result of the floods, were hardly reflected in the official agenda. Press releases and media output failed to mention the demands of citizens who gathered for a spontaneous rally. In her opinion, this upset the balance between internal and external communication and increased the level of mistrust in state information outlets.

Coverage of the referendum on the construction of a nuclear power plant

On 6 October 2024, a national referendum on the construction of a nuclear power plant was held in Kazakhstan. Cases were recorded of staff at some polling stations obstructing the work of journalists. Some journalists were prevented from taking photos or videos, and their movement around polling stations was restricted. In certain cases they were not allowed into the polling stations, and in other cases they were ordered to leave for no apparent reason. Most conflicts were resolved after the rights of media representatives were explained and clarified.

In September and October, in the run-up to the vote, three court cases were registered on charges of breaking electoral law as it concerned public opinion polls. The founder of the Ural Week (in the West Kazakhstan Region) was found guilty of breaking the law by publishing a vox pop interview with city residents in which they expressed their opinions on the upcoming referendum.

This case caused concern among the professional community, as it demonstrated a broad interpretation of the electoral legislation: the prosecutor’s office and the court ruled that the opinion expressed by several citizens about the construction of a nuclear power plant in the context of a vox pop interview for the media constituted a sociological survey.

Media Legislation

- The Law “On Online Platforms and Online Advertising”, which came into force in September 2023, has also been used against independent journalists, bloggers and activists. An article was added to the Code of Administrative Offences of Kazakhstan, concerning liability for the placement and dissemination of false information in the media, or on the Internet. Since this article came into effect, the Foundation for the Protection of Freedom of Speech, “Adil Soz”, monitored 12 trials against journalists and bloggers on charges of spreading false information. In seven of these cases, journalists and bloggers were fined.

- On 5 July, the Kazakh authorities amended the Constitutional Law “On the Republican Referendum“. These amendments guarantee the rights of Kazakh citizens who represent accredited public associations and NGOs, or who are international observers, to attend referendums. Foreign media can also cover events related to the referendum within the framework of the approved procedure. In addition, the new version of the law clearly states that Kazakh and foreign journalists are guaranteed access to cover events related to the referendum, including visits to polling stations. The procedure for the presence of journalists is regulated by the Law, “On Elections in the Republic of Kazakhstan”.

- On 20 August, a new law, “On Mass Media”, came into force in Kazakhstan to regulate the activities of the media. It includes the main provisions of the earlier laws, “On Mass Media” and “On Television and Radio Broadcasting”, which have now been superseded. The concept of “mass media” includes Internet resources, too, clearly distinguishing between these two categories, and granting journalists “special status”. This protects the rights and freedoms of journalists, as well as giving them expanded rights in the exercise of their professional activities. Another positive development is the establishment of a period of limitation of one year from the date of publication for claims made against the media to refute information that does not correspond to reality and defames honour, dignity or business reputation. The period for officials to consider journalists’ requests has also been reduced from seven to five working days.

- On the same day that the Law “On Mass Media” came into force, new accreditation rules for journalists also came into effect in Kazakhstan, approved by order of the Minister of Culture and Information, Aida Balayeva. This set of rules, developed in accordance with the aforementioned law, is called the “Model Rules for Accreditation of Journalists (Mass Media)”. However, even at the discussion stage these rules were criticised by media representatives. In particular, they objected to the requirement that journalists may publish material only in those media outlets through which they obtained their accreditation. This move could significantly complicate the work of freelance reporters who collaborate with several publications.

Furthermore, accredited journalists must now comply with the regulations of events organised by accrediting organisations and observe the access protocol at especially important state and/or strategic facilities. Violation of these conditions twice or more may be punishable by the removal of their journalistic accreditation.

Nine Kazakh journalists challenged these restrictions imposed by the “Model Rules”, and filed a class action lawsuit against the Ministry of Culture and Information. The court dismissed the claim.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

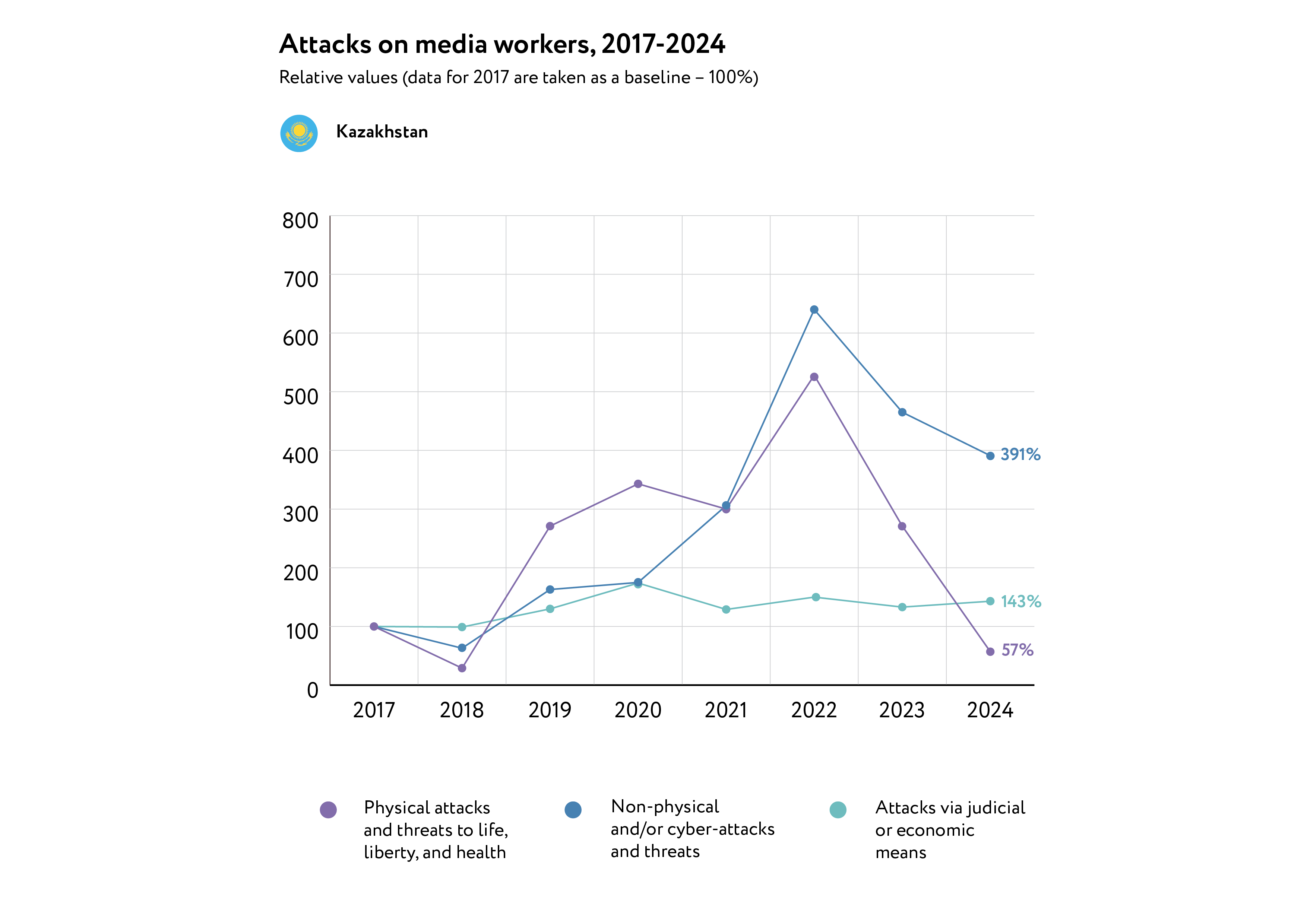

In 2024, 347 incidents were recorded of attacks on journalists. This is a drop of 6% on the number in 2023 (369 cases) and comparable to the levels recorded in 2020-2021 (342 and 314 incidents, respectively). Compared to the peak in 2022 (469 cases, amid the armed riots in January), the number of attacks in 2024 decreased by 26%.

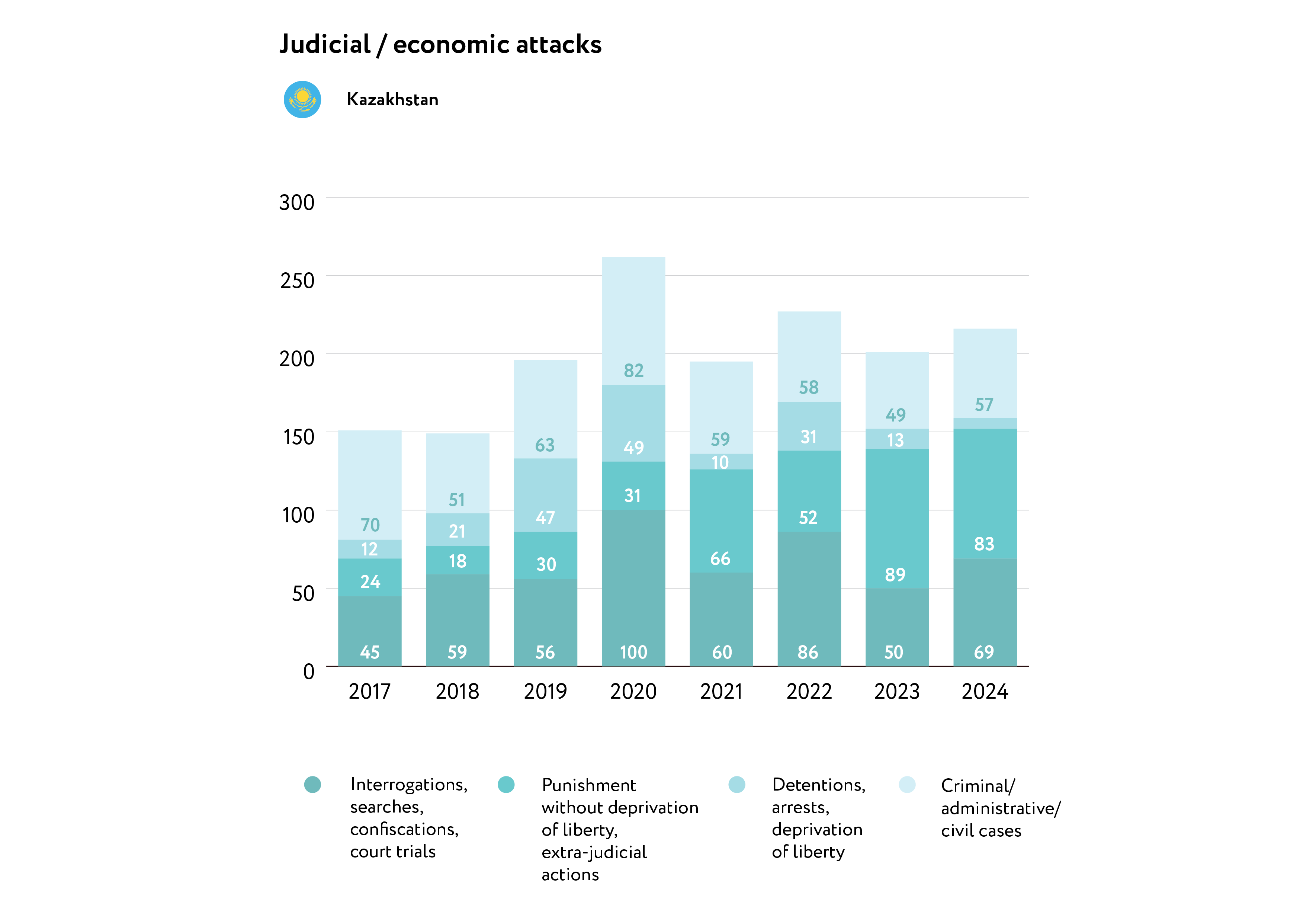

However, compared to 2023 there was an increase in attacks via judicial and/or economic means (+8%, 218 cases). Attacks of this type remain the most common method of applying pressure since monitoring began in 2017. It is worth noting that in 2024, for the first time, the majority of such attacks (55%) were initiated by parties not related to the authorities. They came from private individuals, business representatives, and non-state organisations and groups.

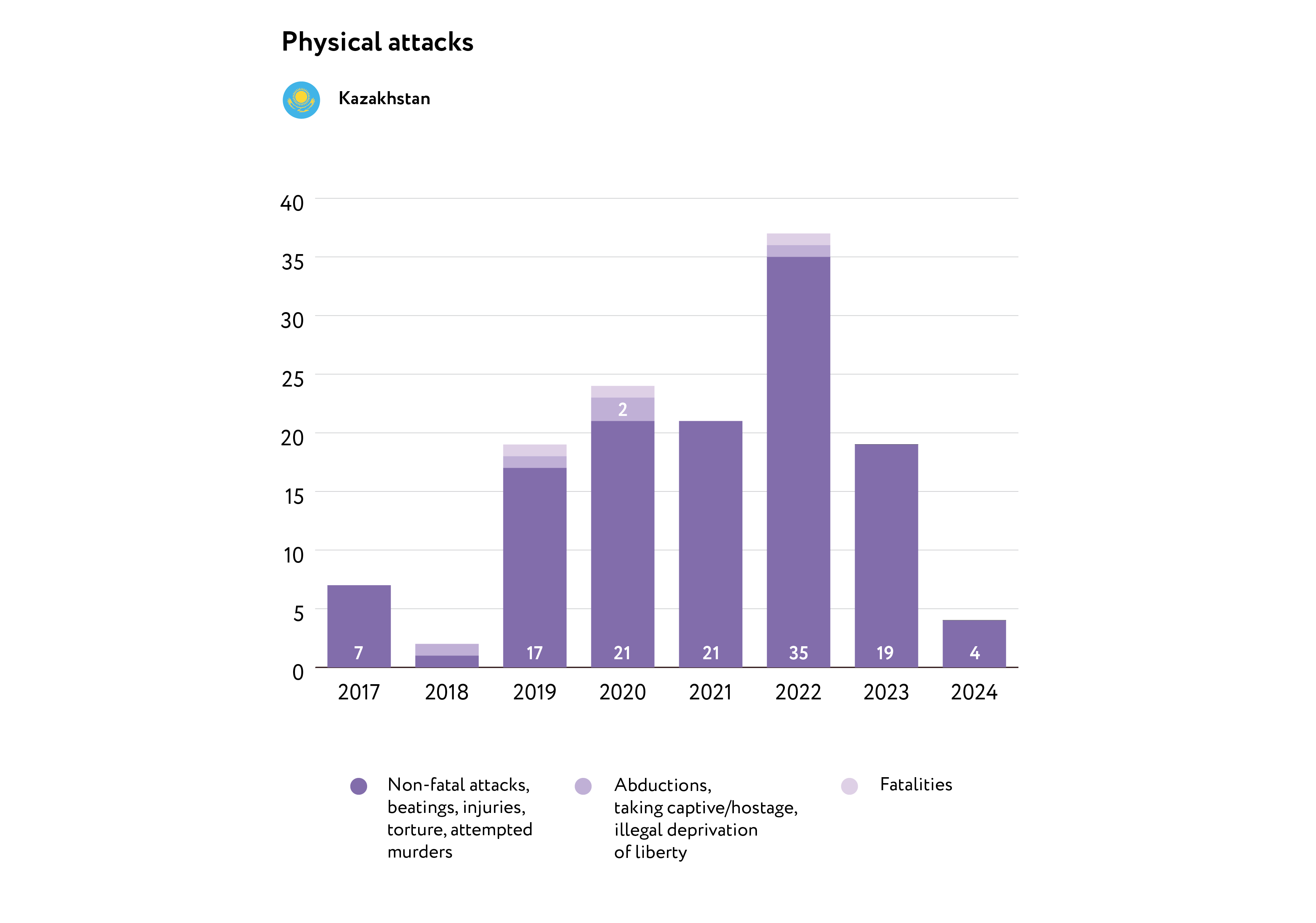

As well as the overall decrease in the number of incidents in 2024, a sharp decrease was recorded in the number of physical attacks and threats to the life and health of journalists: there were – only four cases in the whole year. In three of these cases, the attacks were carried out by individuals not associated with the state. This is the lowest figure since 2018, when only two such incidents were recorded. By comparison, in 2022, when armed riots took place in the country, 37 such incidents were recorded, and in 2023 there were 19.

The main perpetrators of attacks on media workers in 2024 were individuals not associated with government or law enforcement agencies, as well as unknown individuals. Their share of total attacks was 58% (203 out of 347 cases). The dominant types of pressure carried out by them were via judicial and/or economic means (119 cases) by judicial and extrajudicial claims, non-physical attacks by creating obstacles to the professional activities of journalists, and cyber-attacks (81 cases).

Government officials (including foreign state bodies) initiated 144 attacks (41%). Of these, 99 cases involved legal or economic pressure, 44 were cyber threats or other attacks of non-physical nature, and only one incident involved a direct physical threat.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

As mentioned above, there were only four cases of threats to the physical safety of media workers recorded in Kazakhstan in 2024, one of the lowest figures since monitoring began. None of the incidents were fatal.

In three of the four incidents, the threats were carried out by civilians:

- On 19 September, in Petropavlovsk, an unknown man threatened the editor-in-chief of the news agency “Law-Abiding Citizen”, Tolegen Imanov, while he was filming an area affected by floods. The man physically interfered with Imanov’s filming, insulted him, tried to knock the camera out of his hands, and promised to “find him and sort him out”.

- During a joint raid with the police on the night of 20-21 September, Qazmedia.kz journalist, Svetlana Drozdetskaya, was attacked by a drunken man who tried to knock the smartphone out of her hands. The attack was stopped by police officers.

- In a courtroom in Uralsk on 20 November, Talgat Umarov, a journalist for the independent publication Umarovnews.kz, was struck in the jaw by the father of one of the convicts. Umarov maintained that he had done nothing to provoke the attack. The man later apologised, explaining that he lost control because the whole experience in court was very emotional.

The only case of physical abuse by a representative of the authorities occurred on 19 December in Taldykorgan, when a security guard at an administrative building prevented Pravo.kz editor-in-chief, Sabyr Makazhan, from passing through a turnstile. The guard was rude, grabbed Makazhan by his clothes and even pulled out a rubber truncheon, declaring his intention to use it.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

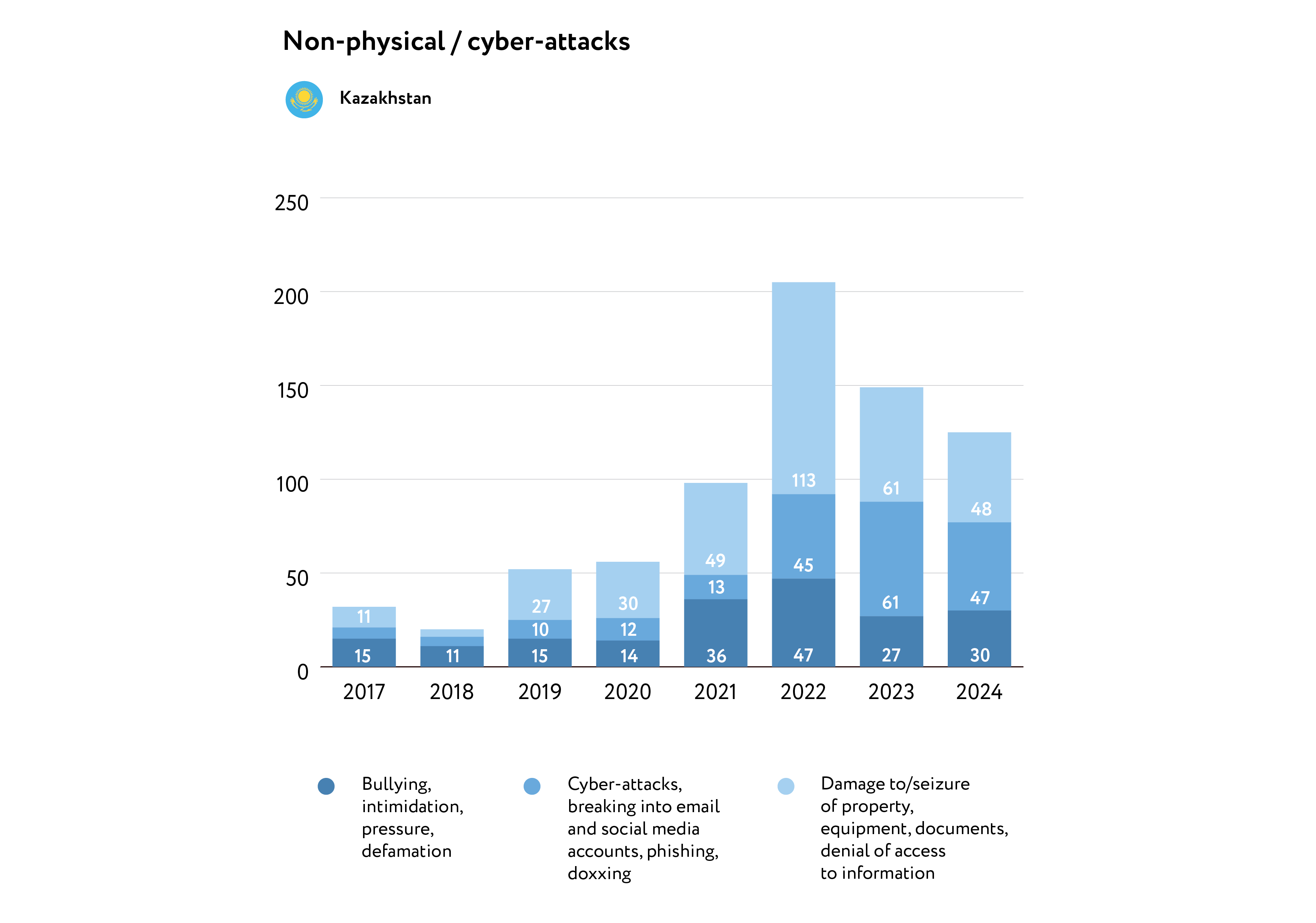

In 2024, there were 125 cases of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats recorded in Kazakhstan, which is 36% of the total number of all incidents. After the worst year for such attacks, in 2022 (when 205 such incidents were registered), this is the second year in a row when the number of such attacks has fallen (in 2022 44% of attacks were of this type, in 2023 they represented 40% of the total number of reported incidents).

In 2024, 35% of these attacks were initiated by government officials, 38% by unknown individuals or people who could not be identified, and 26% by individuals not associated with the authorities.

Illegal obstruction of journalistic activities, including damage/seizure of property and equipment (48 cases), cyber-attacks (27 cases), harassment and threats (including 19 cases Online) remain the primary methods of putting pressure on media workers. It is also worth noting incidents related to defamation and libel against media employees (seven cases) and the dissemination of personal data, phishing and doxing (nine cases).

Of the 48 cases of illegal obstruction of journalists’ activities and deprivation of access to information, 33 came from government officials. Journalists faced restrictions in their work when covering stories which were important for society, such as flooding, high-profile trials, and various other events. Some of these incidents include:

- On 22 January, Ratel.kz journalist Anastasia Bagrova reported that the press service of the Karaganda region Akimat (i.e. administrative or government body) did not notify most of the media about the briefing being given by the Republican Commission investigating the accident at the Kazakhstanskaya mine. According to Bagrova, only two media outlets were officially invited; three more found out about the event by chance; and most journalists were effectively deprived of access to operational information.

- On 7 February an extended meeting of the renewed government was held in Astana. Access for journalists to the participants of the meeting was restricted: – the government press service blocked the doors and elevators to the floor where the meeting was taking place. Journalist Ainur Koskina stated in her Telegram channel AQOSlive that this is the first time media access to such government meetings has been restricted.

- The 17th of March was the third day of the presidential elections in Russia, and Radio Azattyk reporter, Ayan Kalmurat, was interviewing people in a queue at a polling station in the consular department of the Russian Embassy in Astana. He was stopped by police and representatives of the mayor’s office (akimat). One member of staff of the akimat demanded the reporter stop filming and present his accreditation and “permission to film on the street”.

- In Kostanay on 15 April, “Nasha Gazeta” journalist, Andrei Skiba, was covering the registration of applications from flood victims, when he was hassled by security guards in two state institutions. In the Department of Employment and Social Programmes Coordination, a security guard ordered him not to film and demanded that he seek approval from the management. And in the Akimat of Kostanay, a security guard tried to stop Skiba from recording interviews with the victims of the floods.

- On 6 May, KTK TV channel correspondent, Zhanat Moldasheva, was prevented from entering the headquarters of the emergency response centre, located in the building of the Akimat of Atyrau region. She filmed a man in uniform stopping her from carrying out her work and expelling her from the building. Moldasheva tried to enter the room with an LED flood monitoring screen, but she was denied entry, while volunteers and other journalists were allowed in.

- On 10 May, a judge of the Kostanay Regional Court prohibited “Nasha Gazeta” correspondent, Andrei Skiba, from filming or photographing the participants in an open trial, despite the fact that they themselves did not object to the publication of their images in the media.

- On 10 October, a security guard at the Akimat in the Sharbakty district of the Pavlodar region refused permission for Artur Polyakov, a journalist from the “PavlodarNews” news agency, to enter the akimat with his phone, demanding that he leave it at the reception desk. Polyakov explained carefully that the phone was an essential part of his equipment. After being allowed into the district akim’s (mayor or regional head) office, Polyakov faced a similar request from the akim himself.

In six cases, journalists from the Almaty region, the cities of Astana, Karaganda, Shymkent, and Atyrau, reported that members of election commissions were obstructing their work while they were covering voting in the republican referendum on the construction of a nuclear power plant on 6 October. Officials attempted to prevent journalists from entering polling stations and to ban photography and filming.

One incident related to access to information which was especially discussed in the media community was the denial of accreditation to 36 media workers, as well as preventing one journalist from entering a Government building:

- In January, Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs denied accreditation or renewal of accreditation to 36 employees of Radio Azattyk, the Kazakh service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Justifying its decision, the department cited “repeated violations of mass media legislation”. But, according to the Ministry, journalists continued to work without accreditation. On 23 April, the Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty media corporation and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kazakhstan reached a mediation agreement aimed at resolving the situation.

- On 6 September, Press.kz correspondent, Zhaniya Urankaeva, was denied access to Government House (Ukimet Uyi) until the end of December 2024. It was claimed that she had violated the rules on access to the internal facilities in the Government House, in particular, filming outside the press centcre. However, these rules are not publicly available and are classified as “for official use”. After the Adil Soz Foundation appealed to the government, access was restored subject to compliance with established restrictions.

In 2024, the number of cyber-attacks, DDoS attacks (Distributed Denial of Service attacks), hacking and other cybersecurity threats, including identity theft, phishing and doxing, remained high (47 incidents), despite an overall decrease in incidents compared to 2023 (61 incidents). In some cases, such attacks have resulted in media sites being inaccessible to readers:

- On 17 July, Vera.kz’s website was subjected to DDoS attacks that lasted for several hours and came from different IP addresses. The computer of the programmer responsible for the site’s operation was also hacked, and access to the editorial Web-WhatsApp was lost. The site was restored the next day. The editors suggested that the attacks were connected to material published a week earlier which had received an unusually large number of views. A repeat attack was carried out on the website on 20 July, which caused the partial disappearance of archived material.

- The Press.kz website was subjected to a powerful DDoS attack on 12 September, which prevented it from opening. The attack was carried out after the publication of material about the trial of journalist Daniyar Adilbekov. As a result of the attacks, which continued until approximately the end of September, the editorial archive was partially lost, and the website at times became unavailable to readers.

- On 20 December, the Respublika.kz.media website was subjected to a hacker attack: the attackers hacked the server of the hosting company and attempted to completely destroy the resource’s database. The editorial board reports that due to the attack, readers had no access to the website for almost the whole day.

The editorial staff of various media outlets also encountered bot attacks on publications on social networks and massive inflated reactions to them. The tone of bot comments and reactions depended on the topics covered in the publications.

In 28 out of the 47 cases, journalists, bloggers, and online activists suffered from the actions of the attackers (hacking, DDoS attacks, identity theft):

- In July, the YouTube channel of journalist Sanat Ilyas, “Zhalgyz zholaushy” (“Lonely passenger”), which has 154,000 subscribers, was subjected to a hacker attack and then deleted. Ilyas’s YouTube channel had been developing successfully, focusing on material about Kazakhs living abroad.

- Journalist Nazymgul Kumyspaeva, the host of the “Ministers” section of the “I Adore” (“Obozhayu”) YouTube channel, was subjected to telephone attacks and hacking of social media accounts at least ten times during the year.

- The author of the “I Adore” channel, journalist Askhat Niyazov, and the author of the Kozachkov_offside Telegram channel, Mikhail Kozachkov, reported that there had been continuous mass calls from unknown numbers for several hours.

Out of 30 recorded cases of harassment, threats, discrediting and pressure on journalists and bloggers in 2024, 46% (14 cases) came from unknown individuals (it was not possible to accurately identify them with any one group). Government officials initiated 27% of incidents (8 cases); and in the other 27% of cases, threats came from parties not associated with the authorities.

Some of the incidents involving unknown individuals were cyber-attacks, ranging from hacking personal accounts to targeted distribution of threatening messages. In a number of cases, there were attempts to discredit journalists through anonymous offers to other media outlets to publish negative articles about them:

- Journalist Jamilya Maricheva (ProTenge) has faced anonymous threats against her and her family, which she associates with the project’s socially significant activities.

- Blogger Zhenis Omarov warned that his account may be under threat after hackers attacked his colleague and demonstrated their intention to hack his page too.

- An attempt was made to discredit Askhat Niyazov (“I Adore” YouTube channel), when the editorial office of HOLAnews and other media outlets received requests to place paid advertisements criticising the journalist.

- Tamara Yeslyamova (Ural Week) filed a complaint with law enforcement agencies after the appearance of a fake Telegram channel linked to her media outlet with content that violates the legislation of Kazakhstan.

- Mira Khalina (Kursiv.media) stated that bloggers had received requests from anonymous Telegram channels to publish negative material about the editorial staff in return for money.

- Kirill Zhdanov (Press.kz) reported that after he left his previous job, unknown individuals began calling his potential future employers, trying to persuade them not to collaborate with him and his team.

- Ainur Saparova (Azattyk) received direct threats and insults over the phone while covering a protest. An unknown person accused her of “working for the authorities”.

In eight cases, threats were carried out by government officials – employees of an akimat, law enforcement agencies or military personnel. Pressure was applied by demands not to publish material, through direct threats to the journalists’ relatives, putting pressure on their sources of information and threats of violence. Such incidents include:

- While in a temporary detention facility, Daniyar Adilbekov, a journalist and author of the Telegram channel “Wild Horde”, reported through his lawyer that he was being put under pressure from the prosecution. This included threats to arrest his wife; access being denied him to his family; confiscation of his property; and being denied a defence lawyer. A case of coercion to testify was opened based on his statement, but was closed by the prosecutor’s office

- A resident of one of the villages in the Pavlodar region affected by the floods asked Channel One Eurasia journalist, Maya Shuakbaeva, to remove her interview from the TV package, citing threats from unnamed officials. According to Shuakbaeva, officials threatened to dismiss her and her relatives from state institutions, as well as to deny them compensation. Shuakbaeva reported this to the deputy akim of the district and the akim of the region.

- A similar incident was reported by Tolegen Imanov (Law-Abiding Citizen, Northern Kazakhstan), when a woman who featured in his report about the consequences of floods told him that damage assessors contacted her after the report was aired and demanded that she refute what she had said about how rude they were. If not, they threatened to conduct a careless examination of the damage her house had suffered, which would negatively affect the amount of compensation.

- On 8 November, blogger Azamat Sarsenbayev was using a drone to film a flock of birds in the centre of the city of Aktau. When he had finished filming, young men in military uniform approached him, demanding an explanation as to what he was doing. Despite no military unit featuring in what he had filmed, the men tried to detain him. One, wearing captain’s insignia, threatened him with a service weapon, then hit the windscreen of Sarsenbayev’s car several times. The conflict was resolved by the police.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

Attacks via judicial and/or economic means remain the most common method for putting pressure on media workers: they represent 62% of all recorded incidents. In 2024, 218 such attacks were registered, which is 8% more than in 2023 (201 cases).

In 2024, the number of lawsuits increased: 61 cases against 46 in the previous year. The number of interrogations also increased (7 against 2), as well as cases of closure/blocking of media outlets on the Internet (8 against 4). However, the number of detentions decreased by 1.6 times (4 in 2024 against 7 in 2023).

In 2024, 55% of lawsuits (34 out of 61) were initiated by private individuals and companies. Almost 90% of their cases were filed in civil courts and concerned allegations of defamation, illegal use of an image and copyright infringement. In five cases, individuals not affiliated with the state initiated administrative proceedings on charges of defamation and dissemination of false information.

The practice of filing lawsuits by representatives of state bodies continues to be actively used. In 2024, 27 lawsuits were initiated at their request. Of these, 16 cases concerned administrative offenses – slander, defamation, dissemination of false information, violation of election legislation, petty hooliganism, or disobeying a police officer. In 12 cases, the courts sentenced journalists and bloggers to fines or administrative arrests.

- On 12 February, Marina Nizovkina, a journalist of the Atameken Business TV channel, was found guilty of slander by the Shymkent Court of Appeal, and was fined 621,000 tenge (EUR 1,200). The case had been initiated by the deputy head of the Shymkent police because of two posts on her personal Instagram page. This overturned the initial decision to find Nizovkina not guilty and to dismiss the case.

- On 13 May, a court in Almaty fined the founder of the ProTenge project, Dzhamilya Maricheva, for posting and disseminating false information (Part 3 of Article 456-2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Republic of Kazakhstan). She had posted on the Telegram channel about the revocation of accreditation of Radio Azattyk journalists. According to the court, Maricheva had distorted the reasons for the refusal which were given by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- On 1 August, a district court in the Atyrau region arrested the head of the AQIQAT public association, Gaziz Gabdullin,for 20 days on charges of slander. The reason given was a publication on Facebook about corruption and negligence on the part of the district akim. A week later the court of appeal changed the arrest to a fine.

- On 24 September, a court in Almaty arrested Road Control correspondent, Anton Knyazev, for 20 days on a charge of defamation. Knyazev had posted a video on TikTok, where he criticised traffic police for violating traffic rules. He insisted that the video reflected the facts and referred to personal experience when he himself was fined for a similar violation; but the court found his arguments untenable.

- The Prosecutor’s Office of Uralsk opened administrative cases against both the founder of the editorial board of the Ural Week, Journalistic Initiative LLP, and its editor-in-chief, Tamara Yeslyamova,because of vox pop interviews with city residents about the upcoming referendum on the construction of a nuclear power plant. On 3 October, the court found her guilty of breaking the rules of the electoral legislation on conducting a public opinion poll and imposed a fine. However, the court ceased proceedings in Yeslyamova’s case because there was no evidence of an administrative offence.

- On 25 December, Azamat Sarsenbayev, a blogger from Aktau, was subjected to administrative arrest for a period of 10 days for disobeying a request from a law enforcement officer. As requested by media colleagues, Sarsenbayev was filming at the site of the Azerbaijan Airlines plane crash. He claimed that he was a kilometre from the scene of the tragedy, did not interfere with the work of the police and had not been told that filming was not allowed at the time.

Civil trials against journalists and bloggers were held on charges of infringing individuals’ honour and dignity. In addition, the Shymkent police initiated a lawsuit to expel from the country the journalist Marina Nizovkina, who holds Russian citizenship, but is living in Kazakhstan with her family. The police accused her of violating immigration laws and of traffic offences; while public council member Rustem Ashetayev accused her of “interfering in Kazakhstan’s internal affairs” after she published an opinion comment about a candidate for deputy. On 2 May, the court rejected the police claim, noting that Nizovkina’s alleged offences did not pose a threat to the public.

The only criminal case in 2024 concerned journalist Daniyar Adilbekov. He was accused of knowingly making a false denunciation and disseminating false information. The charges were based on publications on the Telegram channel, “Wild Horde“. Statements were filed with the police by a journalist, Gulzhan Yergaliyeva; an Arab representative of Astana airport, Alzhavder Yusuf Rashed M.; and the Vice Minister of Energy, Yerlan Akkenzhenov. According to statements by Yergaliyeva and Rashed M., the case came under the article on dissemination of false information (the maximum punishment under this article is three years in prison); and Akenzhenov cited the article on false denunciation (up to eight years in prison). As part of the investigation, Adilbekov’s home and office were searched and equipment was seized. On 18 October, a court in Astana found Adilbekov guilty and sentenced him to four and a half years in prison. Adilbekov and his defence lawyer continue to maintain his innocence.

ANNEX 1: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (KAZAKHSTAN)

- The International Foundation for Freedom of Speech Protection – a Kazakhstani non-governmental and nonprofit human rights organisation; its main goal is the establishment of free, objective and progressive journalism for the country’s benefit;

- Central Election Commission of the Republic of Kazakhstan – a permanent state body of the Republic of Kazakhstan, which heads the unified system of election commissions of Kazakhstan;

- Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) – an international non-governmental organisation defending journalists’ rights;

- Freedom House – an international human rights NGO that evaluates and publishes reports on the level of freedom in 210 countries and territories worldwide, including on freedom of speech and media activity;

- Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law – a non-governmental organisation whose aim is to promote the observance of civil and political rights and liberties in Kazakhstan;

- KazTAG – the news agency that publishes news about events in Kazakhstan;

- Orda.kz – a Kazakh online media outlet that publishes news, investigations and analytical materials about events in the country;

- The Ministry of Information and Social Development of the Republic of Kazakhstan – a state body of the Republic of Kazakhstan that manages the field of information: monitors the media, has powers to restrict the activities of foreign online platforms or instant messaging services on the territory of the Republic of Kazakhstan in accordance with the laws of the Republic of Kazakhstan;

- Official website of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan

- Radio Azattyk – an international online media outlet that publishes news and analyses with an emphasis on political, economic, and social events in different countries; work of judicial and law enforcement bodies; various cases of persecution of citizens for their political views;

- Reporters Without Borders – an international NGO whose aim is to protect journalists who are being subjected to persecution for doing their job;

- Social media including Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and Telegram;

- Open-access Russian and Kazakh-language media.