PHOTO: On June 4, the Yashnabad District Criminal Court of Tashkent sentenced activist and blogger Murod Makhsudov to seven and a half years in a penal colony.

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Uzbekistan, 89 attacks/threats against professional and civil media workers, and editorial offices of traditional and online media outlets were identified and analysed in the course of the study for 2024. Data for the study was collected using content analysis from open sources in three languages: Uzbek, Russian and English. The report also contains data obtained by an expert from the Justice for Journalists Foundation. A list of the main sources is provided in Appendix 1.

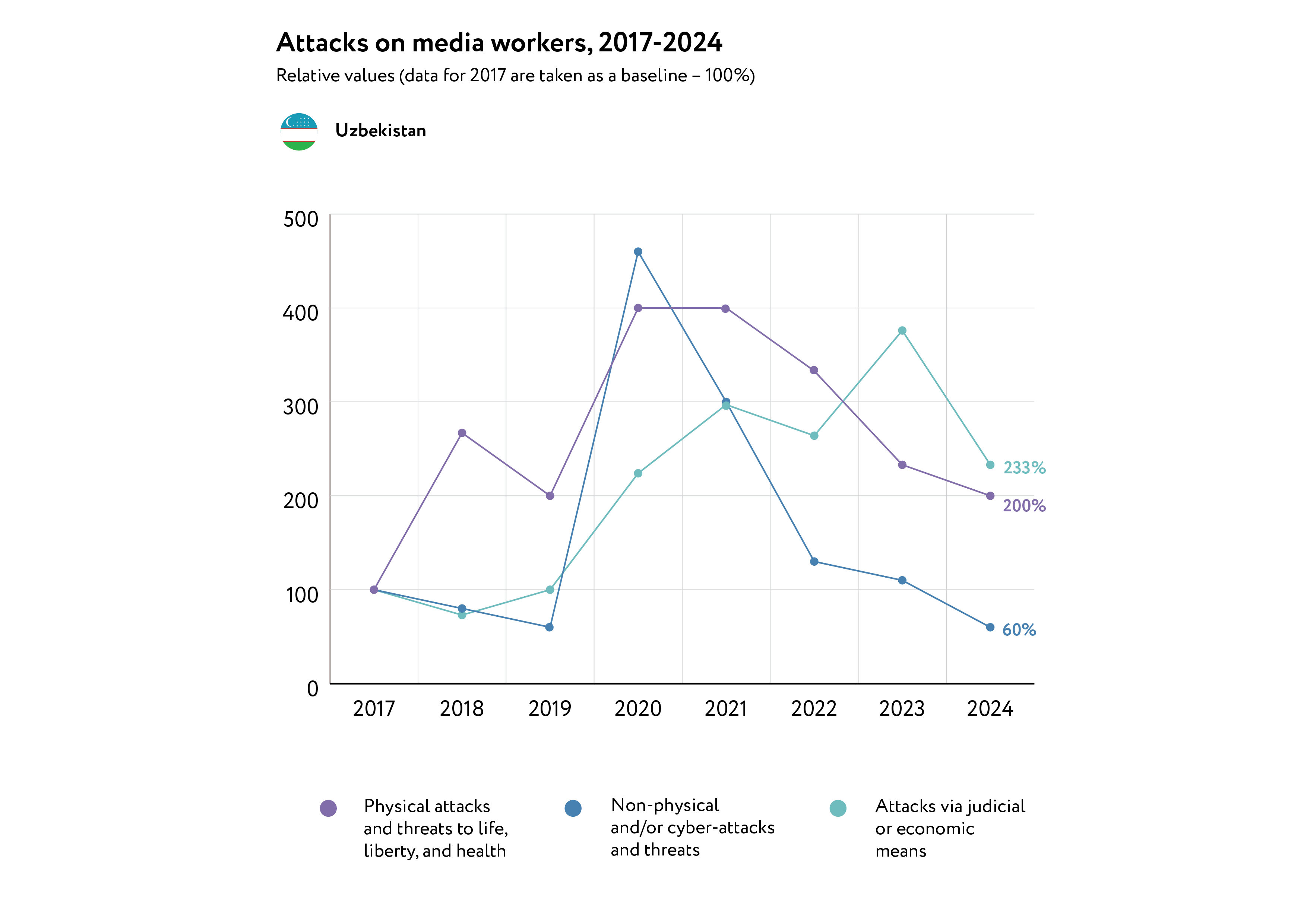

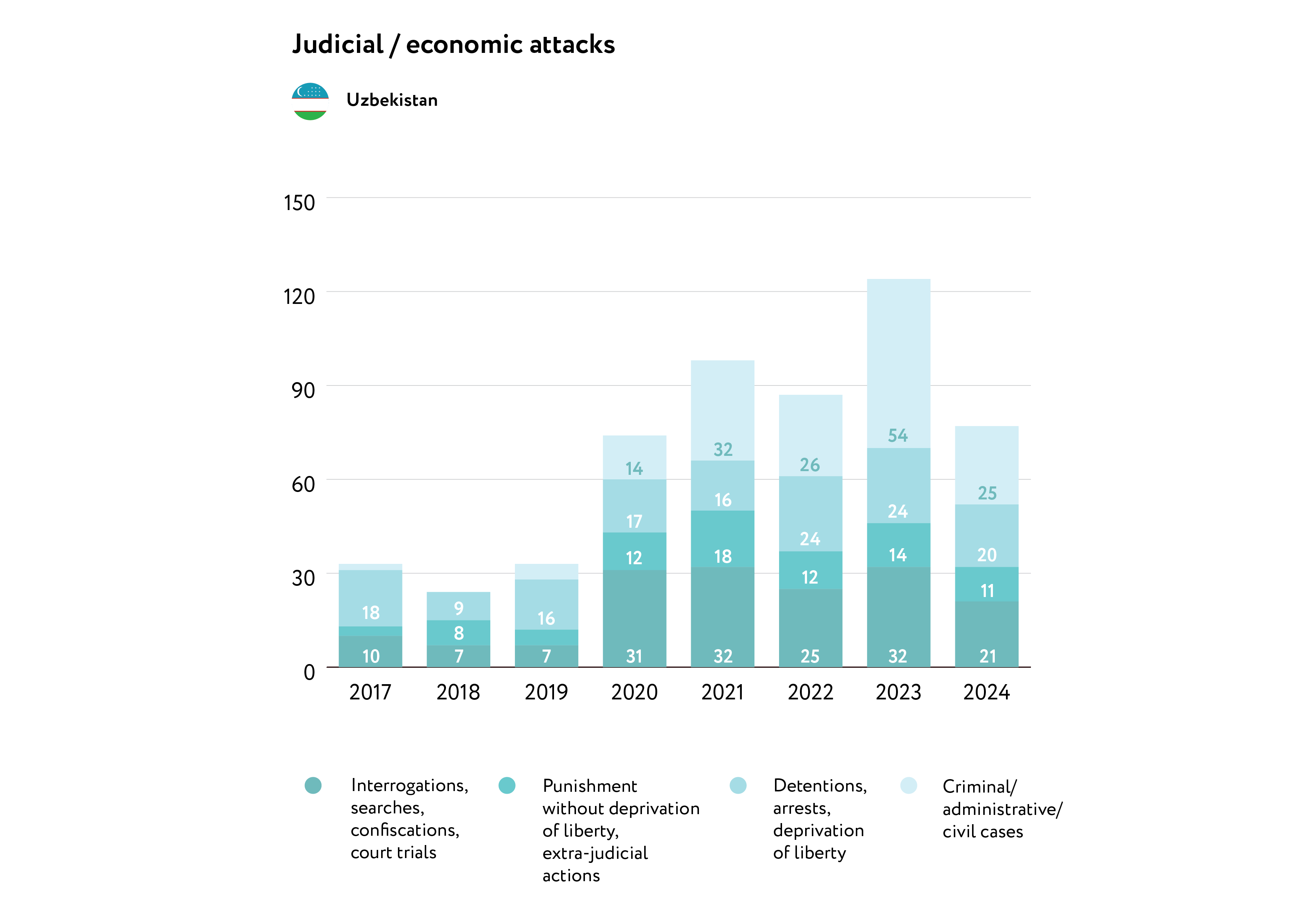

- Despite the fact that the number of incidents using judicial and/or economic means decreased in 2024 (77 cases), such attacks remain the main type of pressure on media workers in Uzbekistan. By comparison, there were 98 attacks recorded in 2021, 87 cases in 2022 and 124 in 2023.

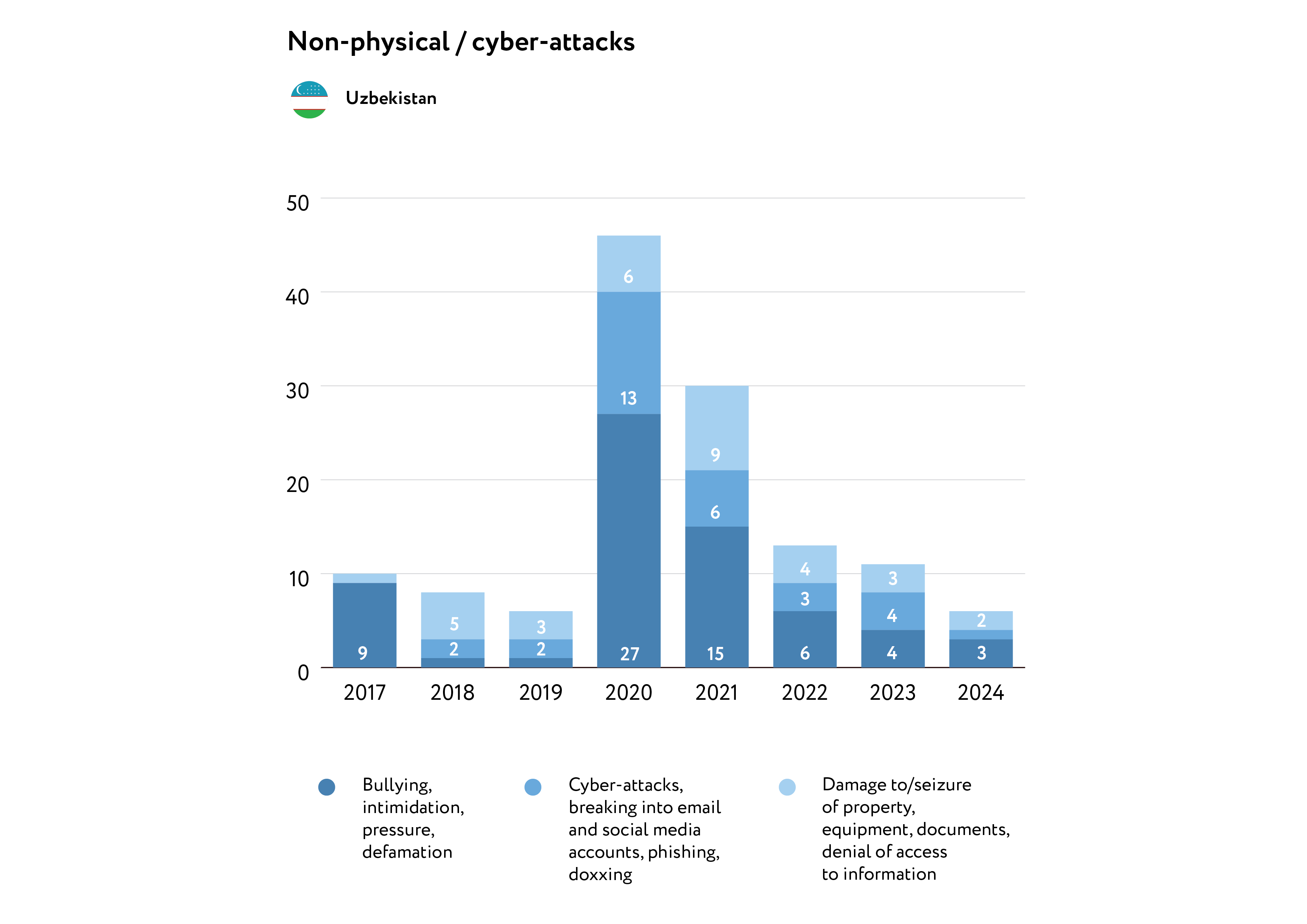

- The number of recorded attacks and threats of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks decreased from 11 to six in 2024.

- The number of physical attacks on media workers remained at the same level as a year earlier.

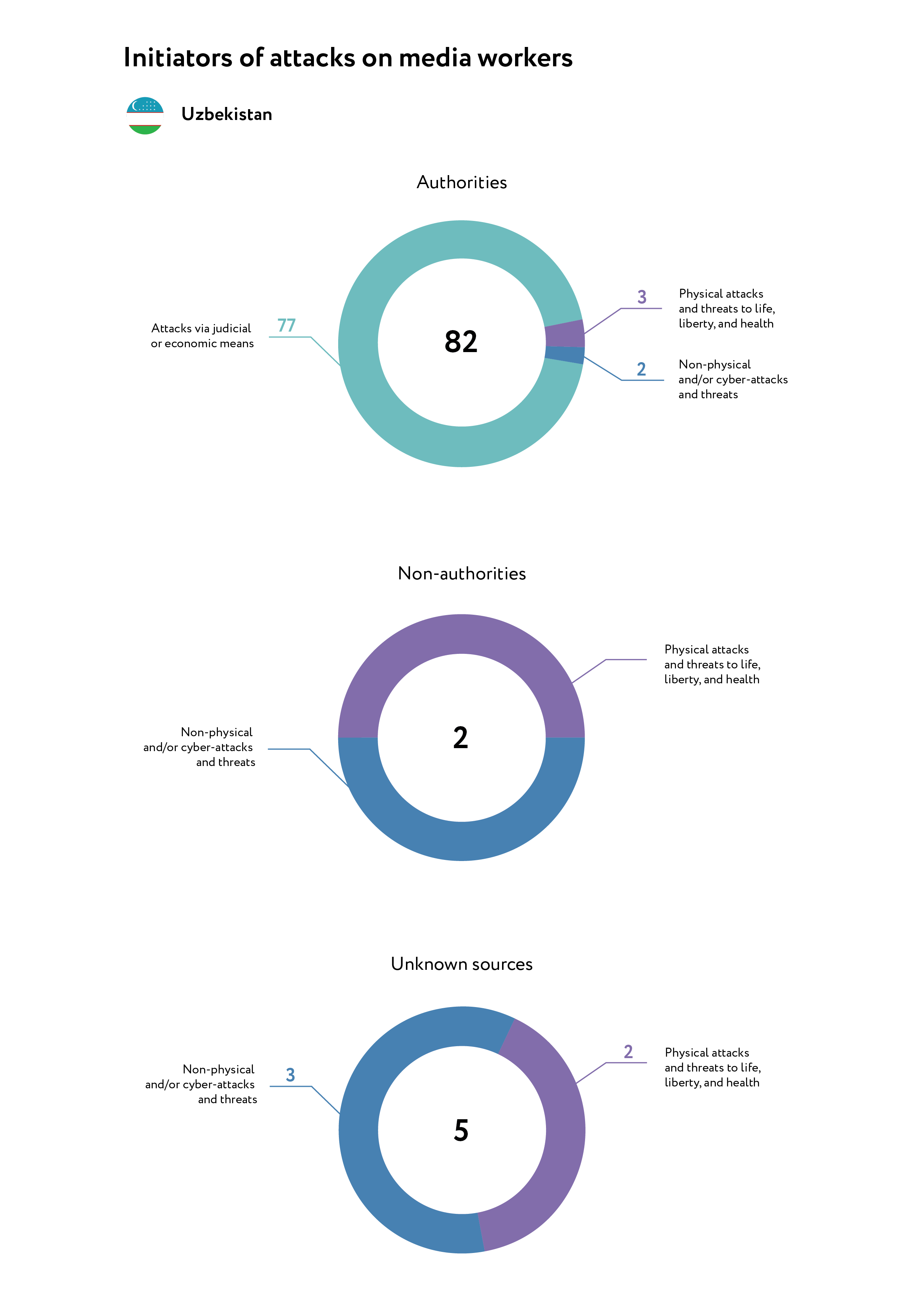

- Most of the attacks were perpetrated by government officials. The main targets were journalists/bloggers who criticized the state or country’s commercial institutions.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN UZBEKISTAN

According to the 2024 annual Press Freedom Index published by the international NGO, Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Uzbekistan ranked 148th out of 180 countries a drop of 11 places from 2023. According to RSF, the authorities largely control the media, and state propaganda continues to dominate the country. The government also controls the blogosphere and online activists, often suppressing any public expression of dissent.

According to the 2024 Freedom on the Net (FOTN) report by Freedom House, Uzbekistan scored 27 points out of 100, remaining in the category of countries with a “not free” Internet.

Traditional media

From 2016 to 2024, the total number of media outlets in Uzbekistan increased from 1,514 to 2,349. For example, the number of magazines rose from 309 to 866, TV channels from 65 to 89 and online media from 395 to 738. Six news agencies were also launched during this period, while the number of Internet users more than doubled, from 14.7 million in 2017 to 31 million. The number of vocal online activists increased 24 times, from 50 to 1,200. At the same time, there was a fall in the number of newspapers and radio stations, from 691 to 600 (a 15% drop) and from 35 to 29 (25% lower) respectively.

The Constitution of Uzbekistan protects freedom of speech and media rights and prohibits censorship. Article 29 of the Constitution guarantees the right to collect and disseminate information. However, at the same time, the legislation does not provide for liability for interference in the work of journalists and media in general.

The criminal and administrative codes of Uzbekistan contain more than two dozen articles that are arbitrarily applied as penalties for the lawful exercise of the right to freedom of expression. Among these are articles for “inciting national, racial, ethnic or religious hatred” (Article 156 of the Criminal Code), “desecration of state symbols” (Article 215), “illegal production, storage, import or distribution of religious materials” (Article 244-3) or “dissemination of false information” (Article 244-6).

In order to implement the citizen’s rights to freely search, receive and disseminate information, the so-called “Strategy Uzbekistan – 2030” was approved by Presidential Decree. The concept of “blogger” was enshrined in the amendment to the law “On Informatization” on August 5, 2014. As specified in Article 3 of this law, a blogger is defined as “an individual who posts on his website and/or other website pages of the global Internet publicly accessible information of sociopolitical, socio-economic and other nature to be discussed by their readers”. The law is formulated in a way that almost all social media users in the Republic of Uzbekistan can be regarded as bloggers, regardless of the intensity of their online activity and the number of subscribers.

On October 19, as part of the Week of International Partnership Initiatives in Tashkent, the director of the Agency of Information and Mass Communications, Asadjon Khojaev, while speaking to media representatives, said that Uzbekistani authorities have developed a bill which provides for the introduction of administrative liability for interference in the lawful activities of journalists. It is expected to be submitted soon to the Parliament for consideration.

Social Media

In Uzbekistan, social networks play a key role in reflecting public demands and have a significant impact on shaping the political opinion of those citizens who actively follow events happening in the country. Many bloggers, striving for sensational publications, often disregard ethical norms, by posting materials that promote violence and misogyny. Some bloggers are also engaged in extortion. Such cases give the authorities an excuse to persecute online activists with a strong public standing, effectively equating them with online criminals engaged in blackmail.

According to Brand Analytics IT company data, there are 587,000 people active on social media each month, excluding Telegram. This is about 10% of all registered accounts in Uzbekistan. Facebook is the most popular, with 201,000 people posting regularly, followed by TikTok with 195,000. Instagram is ahead of Russian social platforms in terms of the number of users from Uzbekistan with 96,000 people compared to 50,900 for Odnoklassniki and 27,000 for VKontakte.

Telegram is the most popular and actively used platform in the country (around 3 million users monthly) with the highest number of messages posted in the Uzbek language: there were 47 million posts in October alone, excluding spam. Facebook and TikTok are in second and third place with 287,000 and 233,000 posts in Uzbek in October, respectively. Instagram sees an approximately equal share of posts in Uzbek and Russian, while on Facebook, the use of the Uzbek language is becoming increasingly common. Among Russian platforms, there were 62,500 posts put on Odnoklassniki and 9,100 in VKontakte.

YouTube is the least popular of all the platforms and does not have a monetization system in place in Uzbekistan.

In 2024, the authorities launched an Interdepartmental Automated System called “Unified Register of Digital Evidence”. It directly affects the activity of users of various media outlets and in the blogosphere. The system has already started monitoring various data not related to state secrets, including photos, videos, audio files, e-wallet addresses, crypto assets, IP addresses, domain names and accounts. Correspondence in Telegram is now officially accepted as evidence in court.

In the first 10 months of 2024, more than 30,000 people in Uzbekistan were prosecuted under the articles “Defamation” and “Insult” of the Administrative Code, and an additional 572 were convicted on the same charges. These measures have significantly increased the level of self-censorship in the blogosphere, forcing many users to be much more cautious about what they say online.

On November 15, 2024, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev signed amendments to the law, “On the Legal Status of Foreign Citizens and Stateless Persons in Uzbekistan”. This gives the authorities the right to regard foreign citizens and stateless persons as “undesirable” if their public actions or statements are seen as a threat to the sovereignty, territorial integrity and security of the country; or if, according to the authorities, they contribute to the incitement of interstate, social, national, racial or religious enmity, or discredit the people of Uzbekistan. If regarded as such, people from these categories may be banned from entering the country for up to five years. These changes reinforce the practice which has already been established of refusing people entry, especially if they are known to create critical content. In addition, the law introduces additional restrictions, such as a ban on opening bank accounts, buying real estate, participating in the privatization of state property, and conducting financial or contractual operations in Uzbekistan.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

In 2024, the lowest number of incidents was recorded since 2020 – 93 cases. As in previous years, attacks via judicial and/or economic means remain the predominant method of pressure, accounting for 88% of the total number of incidents. Compared to 2023, the number of both physical and non-physical attacks has slightly decreased. Nonetheless, in 93% of cases, the attacks were perpetrated by government officials.

Year-on-year monitoring shows that the managers of media outlets and journalists/bloggers refrain from speaking publicly about the attacks, fearing a negative reaction from the special services and the authorities. In recent years it has become a steady tendency that information about attacks on media workers is spread mostly through social networks.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

In 2024, six non-fatal offences were recorded. Some of them were accompanied by damage to/seizure of property.

- On January 5, 61-year-old Shohida Salomov, the creator and administrator of the Telegram channel “Pathanatomy of the Land of Uz” and the YouTube channel “Shakhina Salomova”, who has been held in a mental hospital for more than a year, was transferred to a psychiatric clinic following a court decision to tighten her detention regime. The reason given for the transfer was her refusal to take prescribed medications, which, according to Salomova, had troubling side effects.

- On January 8, blogger Farrukh Abdullayev reported to the internal affairs authorities of the Fergana region that he was insulted and beaten by a stranger, who also took his phone. The complaint was registered in accordance with established procedures.

- On February 6, in the Bukhara region, Ulmas Tulayev, a journalist from the TAFTISH news agency, was stabbed in the stomach. The incident occurred in a café in the Shafirkan district. A quarrel arose between the journalist and another customer, during which the man grabbed a knife and stabbed Tulayev. Tulayev was taken to the hospital. The district prosecutor’s office opened a criminal case under Articles 25 and 97 (“Attempted premeditated murder”). On February 7, a suspect was taken into custody.

- On June 20, the former editor of the independent Karakalpak newspaper “El Khyzmetinde”, Dauletmurat Tajimuratov, was beaten by officers of penal colony No. 11 in Navoi Province while in custody there, because of a dispute over a parcel the journalist had received from his mother. Four officers restrained him, while the fifth struck him. On the eve of Tazhimuratov’s transfer from prison to the colony with a softer detention regime (according to court sentence, his term under strict conditions was due to expire on July 5), the head of the prison threatened that a case of “regime violations” would be fabricated against him in the new place and he would be returned to prison.

- On July 29, local blogger Umid Miraliyevand his younger brother were beaten in Kashkadarya. The blogger claims that the beating was ordered by the local authorities and that as a result he became disabled. According to him, the people who attacked him went unpunished.

- On September 9, police officers in Samarkand blocked all entrances to the house of blogger Bakhodur Khasanov and forcibly dragged him out of the house. Before the start of his trial, Khasanov was beaten by police officers of the Samarkand district. According to him, the video confirming the beating was sent to the prosecutor’s office, but no measures were taken against the police. The blogger is known for his social content focusing on social and domestic problems, and the unlawful actions of government officials and personnel from the Ministry of Internal Affairs. On September 10, a court in Samarkand fined Khasanov $200 and sentenced him to ten days’ arrest on charges of “insult” and “petty hooliganism.”

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

The number of recorded non-physical attacks continues to decline year by year. In 2024, six such incidents were recorded. By comparison, there were 11 cases recorded in 2023, 31 in 2021 and 46 in 2020. The decrease is due to the fact that media editors prefer not to report threats against their staff. Bloggers also often choose to keep silent about the non-physical attacks they face.

There are three main types of non-physical attacks in Uzbekistan: harassment, cyberattacks and unlawful obstruction of media activities. The incidents recorded in 2024 include:

- Throughout January, unknown individuals were leaving comments on the independent media website Asiaterra.info, using obscene language and threats against the author of critical articles. The commentators were particularly angry with articles about a bill which would make it illegal to discredit law enforcement agents and about repressions in Karakalpakstan. These articles were seen by them as direct criticism of the top leadership of Uzbekistan.

- On June 28, officers of the Mirishkor district Department of Internal Affairs of the Kashkadarya Region visited the home of Yusuf Ruzimuradov, a former political prisoner and creator of the video blog “Dunyo va Siyosat”, who now lives in exile. The State Security Service instructed Yusuf’s brothers to call him and intimidate him in order to stop him from broadcasting content critical of the authorities.

- On July 22, businessman Abdurakhmon Abdurakhmonov from the Yangiyul district parked a car with four men inside and tinted windows close to the house of Lilia Nikolenko, the administrator of the Telegram channel “Consumer.Uz”. Their open surveillance of her movements was a deliberate attempt to put psychological pressure on Nikolenko. This was because she had published information about alleged violations committed by Abdurakhmonov’s multimillion-dollar empire in the entertainment business.

- On September 28, unknown persons hacked the Telegram account of Shukhrat Latipov, an investigative journalist for the online media outlet Gazeta.uz. The hacks were carried out from Luxembourg (via smartphone) and Turkey (via computer). As a result, contacts, correspondence and files were compromised. The journalist is certain that he is “under surveillance by those who do not like his work”.

- On October 23, the Central Election Commission (CEC) refused permission for the Hook.report team to observe the parliamentary elections. The independent newspaper applied for accreditation exactly ten days before election day; however, they were asked to provide additional documents not required by law. These documents were immediately sent to the CEC email, but the newspaper was still denied accreditation for “failure to comply with the application deadlines”.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

As in previous years, attacks through legal and/or economic means, continue to be the main method of putting pressure on media workers in Uzbekistan. In 2024, at least 8 bloggers were sentenced to prison terms ranging from five to seven and a half years:

- On January 29, the Nishan District Criminal Court of the Kashkadarya region found the administrator of the Telegram channel “Achchiq haqiqat” (“Bitter Truth”), Abdulkhakim Abjalilov, guilty of extortion and sentenced him to five years in a penal colony and ordered him to pay 1 million soums ($77) as compensation to one of the two victims. The blogger was accused of committing a crime under paragraphs “a” and “c” of Part 2 of Article 165 of the Criminal Code of Uzbekistan (“Extortion committed repeatedly or by a dangerous recidivist by prior conspiracy by a group of persons”).

- On March 20, the Nukus District Court sentenced Salamat Seitmuratov, the founder of the Halyk TV channel, and Mustafa Tursynbayev, the creator of the Nukus Online video channel, to five years in prison under three articles of the Criminal Code of Uzbekistan: extortion, fraud and bribery.

- On June 4, the Yashnabad District Criminal Court of Tashkent sentenced activist and blogger Murod Makhsudov to seven and a half years in a penal colony. At a closed court hearing, the blogger was found guilty under paragraphs “a” and “d” of part 3 of Article 139 (defamation committed for mercenary or other base motives and combined with an accusation of committing a grave or especially grave crime), paragraph “b” of part 2 of article 165 (extortion committed on a large scale) and paragraphs “b” and “d” of part 2 of article 167 (theft by misappropriation or embezzlement of someone else’s property, committed repeatedly and by abuse of office) of the Criminal Code of Uzbekistan. Makhsudov was arrested on October 24, 2023, and had been awaiting trial in pre-trial detention centre No1 (known as “Tashprison”).

- On July 18, the Karshi Criminal Court sentenced bloggers Dildora Khakimova, Nargiza Keldiyorova and Shukrullo Parpiev to six years in prison. They were arrested on suspicion of committing a crime under Part 3 of Article 165 (“Extortion”) of the Criminal Code. According to the press office of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, they were caught with physical evidence while extorting $5,000 from the school principal in exchange for not disseminating personal information about him and his father on the Internet. In addition, Keldiyorova was charged under Article 155 (“Terrorism”) and Part 3 of Article 158 (“Public insult or slander against the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan, using the Internet, press or other media) of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

- On November 22, the Chilanzar District Criminal Court of Tashkent sentenced blogger Kabul Dusov to one year’s restriction of liberty for insulting Deputy Minister of Preschool and School Education, Farhod Bokiyev. Dusov was found guilty under paragraph “a” of part 3 of Article 140 of the Criminal Code (“Insult in connection with victim’s official or civil duty”). On January 26, 2025, the court changed his sentence of restriction of liberty, to imprisonment in a penal settlement. The court’s decision was based on the assertion that, despite the ban, Dusov continued to actively use the Internet.

Prosecution based on Administrative Code articles and mild punishments such as detentions for up to 15 days, as in previous years, were actively used to pressure media workers:

- On January 14, Mikhail Dovlatov, a journalist for the online media outlet Nuz.uz, was unlawfully detained for five hours by people in civilian clothes during his journalistic investigation. Dovlatov said that a group of men who did not introduce themselves forcibly dragged him into the office and snatched his phone as soon as he took it out. Next, they drew up a protocol against him for violation of the law banning smoking in public places and additionally fabricated a case under Article 194 (“Failure to comply with the lawful demands of the representatives of the internal affairs bodies”) of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Republic of Uzbekistan. After the phone was returned to him, he found in it an SMS notification of a fine, which was imposed without a trial. On January 16, at the court hearing in the Uchtepa District Criminal Court, Dovlatov was charged under Article 183 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (“Petty hooliganism”) for smoking outside of a designated area. The charges of disobeying the authorities were dropped.

- On April 11, blogger Shyngys Tairov was detained by law enforcement officers. He was charged under Article 202-1 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (“Inducement in the activities of illegal non-governmental non-profit organizations, movements, or sects”). The Nukus City Court ordered that the blogger be placed under arrest for 15 days and that his social media accounts be blocked. The grounds for such measures were not stated in the court decision. Tairov appealed against the verdict, and on April 20 the term was reduced by the Court of Appeal to eight days’ arrest, that is, the time he actually served.

- On June 19, the Termez City Court considered an administrative case against local blogger Fazilat Salimova. She was found guilty under Article 195 (“Obstructing personnel of the internal affairs bodies in the performance of their official duty”) and Part 1 of Article 202.2 (“Dissemination of false information”) of the Code of Administrative Responsibility of Uzbekistan. The court sentenced her to eight days’ arrest and a fine of 3 million 400 thousand soums ( $262).

- On October 9, a court in Tashkent sentenced bloggers Kamal Yusupov and Abror Gulyamov to 15 days’ arrest for a humorous video on the YouTube channel of the Brbalo music group. The case was opened after four unnamed citizens filed a statement indicating that “the video contradicts the ethical norms and traditions [of Uzbekistan], and also negatively affects the education of young people and children”. The court charged the bloggers under Article 183 (“Petty hooliganism”) and under Part 1 of Article 194 (“Failure to comply with the legal requirements of the internal affairs bodies”) of the Code of Administrative Responsibility of Uzbekistan.

Other recorded incidents include:

- On February 24, officers of the Department of Internal Affairs of the Mubarek District in the Kashkadarya Region detained blogger Guli (Gulnoz) Mirzayeva on suspicion of extortion. Although the Department did not comment on the situation, activists in Kashkadarya confirmed her arrest, believing that it is directly related to content she published exposing corruption at the Mubarek Gas Processing Plant. Mirzayeva allegedly “demanded money in exchange for renouncing criticism of the plant’s management”.

- On February 28, Ibrat Safo, a journalist from the BBC’s Uzbek service who has been living in London since 2017, said that he had been invited “for a conversation” at the Chilanzar District Department of Internal Affairs in Tashkent. “Before ‘finding’ me, [the police officer] twice disturbed my 68-year-old sister, who works as a teacher, and told her to come to the Chilanzar police department. I told my sister not to go”, Safo said. According to him, this is the first time this has happened in the 20 years that he’s been working as a BBC journalist in London.

- On July 15, the blogger of the YouTube channel “DETEKTIV UZ”, Sherali Komilov, was detained in the village of Durmon, Kibray district. With the investigator’s permission, a search was carried out in his house, and his belongings and equipment were seized. A month before his arrest, Komilov said in an interview with Radio Ozodlik that within a year three criminal cases had been opened against him on charges such as fraud, slander and insult.

- On August 2, journalist and poetess Shakhzoda Bakhranova (online pseudonym, “Shahina Abdurazzok”) from the city of Karshi was detained in Tashkent. This happened immediately after she had spoken on the phone with her mother and told her that she had safely arrived in Tashkent. Shortly after this she completely disappeared. Her Facebook profile was deactivated and her Telegram channel was blocked. It became known only later, that she had felt unwell during the interrogation at the internal affairs department and was urgently taken to a nearby hospital.

- On December 1, the film crew of Russian journalist Alexei Pivovarov (YouTube channel “Redaktsiya”(“Editorial”)) was detained in Nukus together with Hook.report employee Feride Makhsetova. The detention happened because of a statement received by the authorities from a city resident. In the evening, the journalists were released from the Nukus police department. However, the officers seized all footage filmed by the journalists in Karakalpakstan.

ANNEX 1: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (UZBEKISTAN)

- AsiaTerra – an information and analysis website covering Central Asia

- Brand Analytics – an IT company and developer of Brand Analytics, a leading system for monitoring and analysing social media and media

- Radio Ozodlik – the Uzbek Service of Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty

- Gazeta.uz – a news website specializing in Central Asian news

- Kun.uz – a news website specializing in news about Uzbekistan

- Mediazona.Central Asia – an information and analysis website covering Central Asia

- Podrobno.uz – a news website specializing in news about Uzbekistan

- Hook.report – a news website specializing in news about Uzbekistan

- Nova24.uz – a news website specializing in news about Uzbekistan

- IPHR (International Partnership for Human Rights) – an international non-governmental human rights organization based in Brussels, Belgium

- Tmhelsinki.org (The Turkmenistan Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights) – a non-governmental organization, based in Bulgaria, for the promotion of human rights in Turkmenistan