The following report presents the key findings of an analysis of attacks in relation to the workers and editorial offices of traditional and online publications in 12 post-Soviet countries for the year 2020.

For the purposes of this report, the term “media workers” is understood as professional and citizen journalists, bloggers, online activists, camera operators, photo correspondents, and other employees and managers of traditional and non-registered media.

AUTHORS OF THE REPORT

- Azerbaijan: Khaled Aghaly

Lawyer and specialist in media law in Azerbaijan. Aghaly has been working in the field of media law in Azerbaijan since 2002. He is one of the founders of the Media Rights Institute (MRİ Azerbaijan). The Media Rights Institute was forced to suspend its activities in 2014. Since then, Agaliev has been working individually. He is the author of more than 10 reports and studies on the state of media rights in Azerbaijan.

Non-profit journalistic non-governmental organisation. It was officially registered on 16 January 2003. Throughout its existence the organisation implemented more than 40 projects. The Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression is a member of the Armenian National Platform of the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum and has actively taken part in the activities of the Forum.

The main direction of the CPFE activity is the monitoring of the free speech situation in Armenia, detection of and responding to the violations of the rights of journalists and the media, as well as drafting and publication of periodic reports on the basis of the above data. The CPFE also takes practical steps to protect the rights of the media and their representatives, including before courts. An important area of the Commitee’s activities is the improvement of the media-related legislation. With a view to this, the CPFE drafts new legislation and amendment packages and submits them to the parliament.

The Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ), is a non-governmental, non-profit and non-partisan association of media workers, promoting freedom of expression and independent journalism ideas in Belarus.

The main goal of BAJ is to facilitate the exercise of civil, social, cultural, economic and professional rights and the pursuit of legitimate interests of its members, help to develop expertise and get a chance for creative self-fulfillment, as well as to create conditions that enable freedom of the press, including the journalists right to obtain and impart information without any interference.

The main tasks of BAJ activities are:

- BAJ protects journalists’ rights and legitimate interests in state bodies and international organizations;

- BAJ helps to create material, technical, organizational and other facilities, vital for improving journalist proficiency;

- BAJ is drawing up an effective program to develop mass media so that it would create favorable conditions for their functioning in Belarus;

- BAJ establishes relations with journalist organizations all over the world.

- Georgia: Oleg Panfilov

Georgian journalist, commentator and writer. Author of 52 books and of more than one hundred TV programmes about Georgia. He has won various international prizes and is a Cavalier of Georgia’s Order of Honour. In the 1990s, he headed the Moscow bureau of the Committee to Protect Journalists (1992-1993), and was in charge, from 1994 to 1999, of the monitoring service of the Glasnost Defence Foundation in Moscow, before setting up the Centre for Journalism in Extreme Situations (Moscow) of which he was director from 2000 to 2010.

Major priority of International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech “Adil Soz” is establishment of open civil society over the statement in daily life of the country free, objective and progressive journalism. The main activity of the Foundation is monitoring of violations of freedom of speech, legal activity, educational activity and legal help to journalists and mass media.

School of Peacemaking and Media Technology is a nonprofit media development organization encouraging freedom of expression, diversity, researches and training on media issues based in Bishkek.

- Crimea: Human Rights Centre ZMINA

A non-governmental organisation, which aims to promote the human rights, the rule of law and the ideas of civil society in Ukraine.

One of the most important Moldovan non-governmental organizations providing assistance to independent media. API was founded in 1997 by the representatives of the first local independent newspapers.

API promotes press freedom and highly appreciated for its media campaigns in various public interest sectors, advocacy activities for mass-media development, defense of the freedom of expression, access to information, promotion of journalistic self-regulation, etc. API’s slogan is: “For a professional, objective and strong press”.

Since 2015, API and three other media NGOs organize yearly Mass-media Forum in Republic of Moldova, for discussion the problems and challenges faced by the journalistic community and draft a Roadmap for media development in Moldova.

Justice for Journalists Foundation is a London-based charity whose mission is to fight impunity for attacks against media. Justice for Journalists Foundation monitors attacks against media workers and funds investigations worldwide into violence and abuse against professional and citizen journalists. Justice for Journalists Foundation organises media security training and creates educational materials to raise awareness about the dangers to media freedom and methods of protection from them.

- Tajikistan: Partner, who preferred to stay anonymous

- Turkmenistan: Ruslan Myatiev, Turkmen.news

Turkmen journalist, human rights activist, and editor of the news and human rights website Turkmen.news – one of the few independent sources covering Turkmenistan. The website is based in the Netherlands, where it was set up in 2010.

Myatiev frequently writes and broadcasts for the media and speaks at various international conferences and seminars as a Turkmen expert on socio-economic subjects, on politics and human rights. Ruslan Myatiev is Turkmenistan expert for the Justice for Journalists Foundation.

- Uzbekistan: Sergei Naumov

Freelance journalist for major media outlets – Fergana.ru (Russia) and IWPR (UK). From 2008 to 2017 he authored several reports for international organisations and regional online forums on the state of freedom of speech, expression and the press in Uzbekistan. He is an active participant in the country’s activist movement. From 2007 to the present day he has been monitoring the use of child labour on cotton plantations, creating human rights content, and participating in the research projects of European human rights organisations. Naumov has been a volunteer at the School of Peacekeeping and Media Technology in Central Asia (Kyrgyzstan) since 2014.

The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU) is the biggest organisation that brings together journalists and other media workers in Ukraine. The union is an independent public non-profit organization. The mission is the development of journalism and media in Ukraine and protection of freedom of speech and journalists` rights.

NUJU cooperates with international organizations and institutions of the United Nations, the EU, the Council of Europe, the International Federation of Journalists, the European Federation of Journalists, the RFS (Reporters Without Borders) and communicates with foreign professional media organizations, concludes agreements with them on cooperation in the field of professional activity, exchange of information, establishment of journalistic exchanges (Poland, Belarus, China, Lithuania, Germany, Italy, etc.).

NUJU conducts conferences, public hearings on the topic of freedom of speech and the safety of journalists actively participates in the preparation of changes in the Ukrainian media law, provides legal support for journalistic activities, co-organizer of different forums, festivals, promotions, press tours, seminars, etc.

PHOTOGRAPHERS:

- Armenia — Photolure News Agency

- Azerbaijan — Firi Salim

- Belarus — Vadim Zamirovsky, TUT.BY photographer

- Georgia — Mariam Nikuradze, co-founder of OC Media

- Kazakhstan — Madina Alihmanova, the international news agency KazTAG

- Kyrgyzstan — Bermet Malikova, Internews

- Crimea — Human Rights Centre ZMINA

- Moldova — TV8

- Russia — Yuri Beliat, photo correspondent MBK Media

- Tajikistan — RFE/RL’s Tajik language service — Radio Ozodi

- Turkmenistan — Nurgeldy Khalykov (photo from the personal Instagram account)

- Uzbekistan — kun.uz

- Ukraine — The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine

METHODOLOGY

The data for the research was obtained from sources in the English, Russian, and state languages of the countries being analyzed, including social media, using the method of content analysis. Lists of the main sources are presented in Annexes 2-14. Additional data was obtained using the method of expert interviews with media workers, who were reporting to the Foundation’s partners about incidents that had not been made public in traditional and social media. All information about these attacks has been corroborated by the Foundation’s experts from three or more unrelated sources.

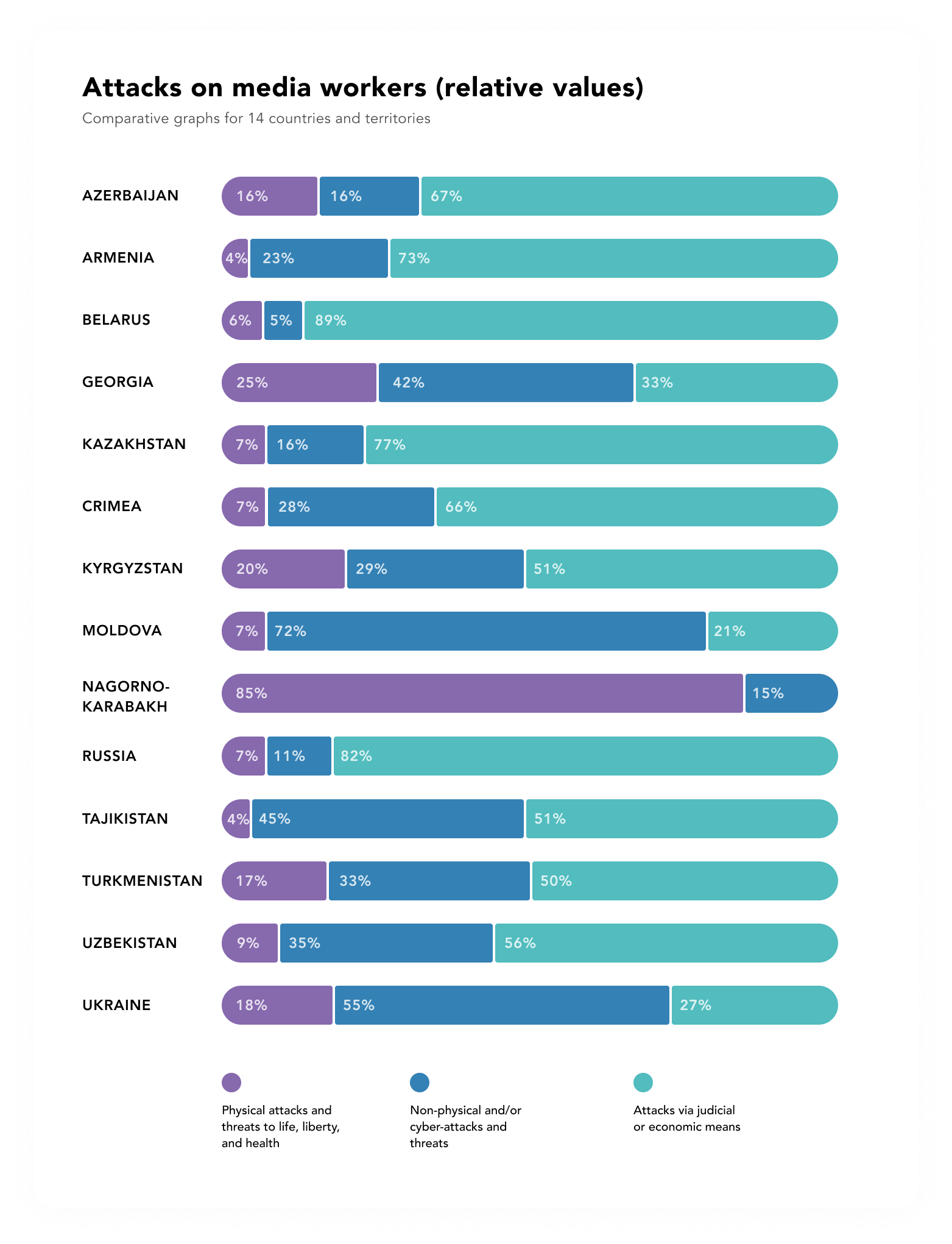

4,611 attacks were registered in 2020 in relation to media workers and the editorial offices of media outlets. Each incident was placed in one of the following categories of attacks:

- Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health

- Non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats

- Attacks via judicial and/or economic means

Each of the indicated types of attacks was further divided into subcategories. A complete list of the methods of assaults on media workers is presented on the Foundation’s website and in Annex 1.

For the purposes of more precisely reflecting combination assaults on media workers in 2020 we are introducing a new category – hybrid attacks.

We are calling systematic persecution of publications or media workers with the use of tools from two or more categories of assaults – physical, non-physical, and judicial/economic – “hybrid”. Such a combination of means, involving and not involving force with judicial means of pressure on undesirable journalists, is carried out with a view to demoralising them or getting them to self-censor or to abandon the profession or even life itself.

PRINCIPAL TRENDS

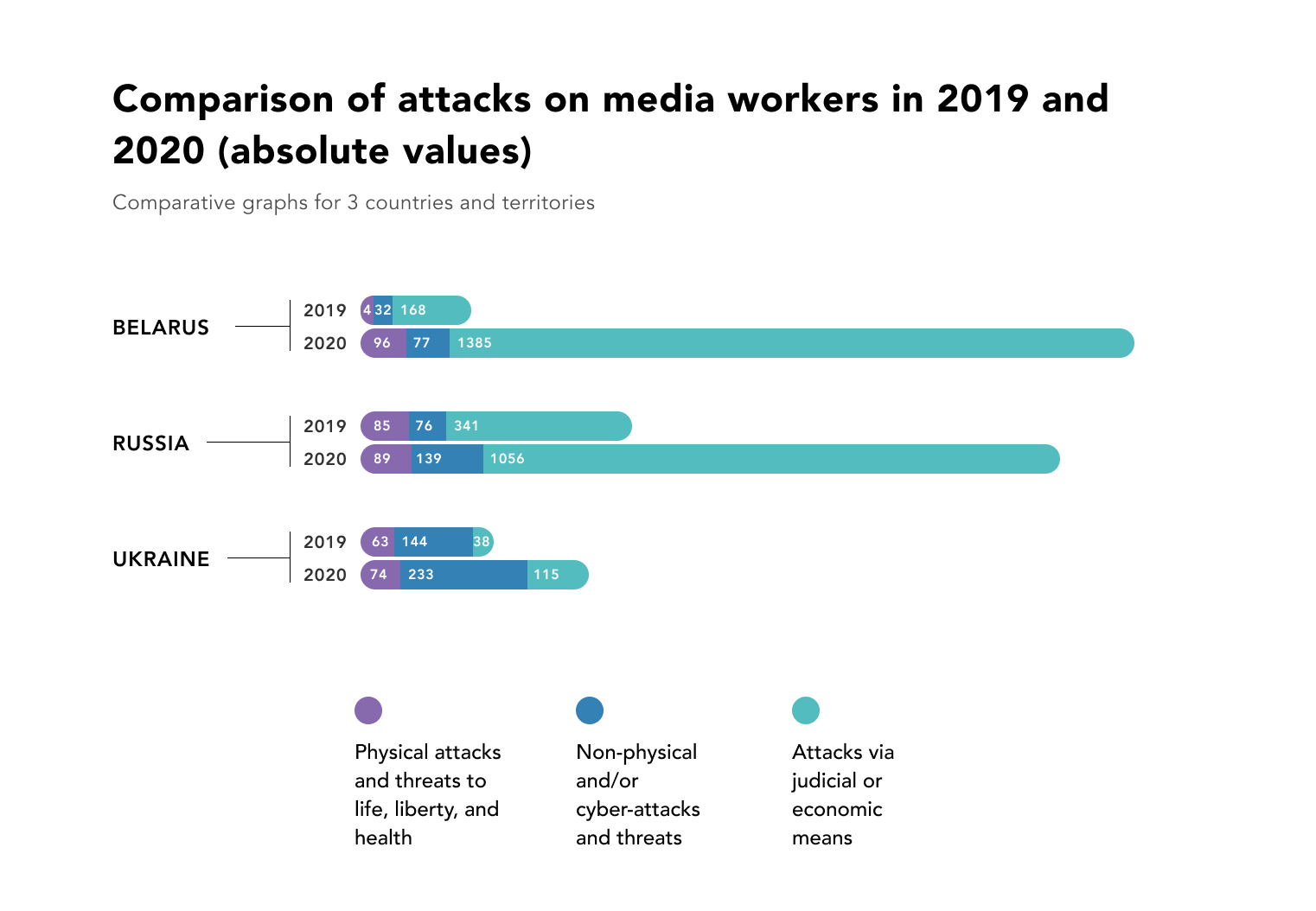

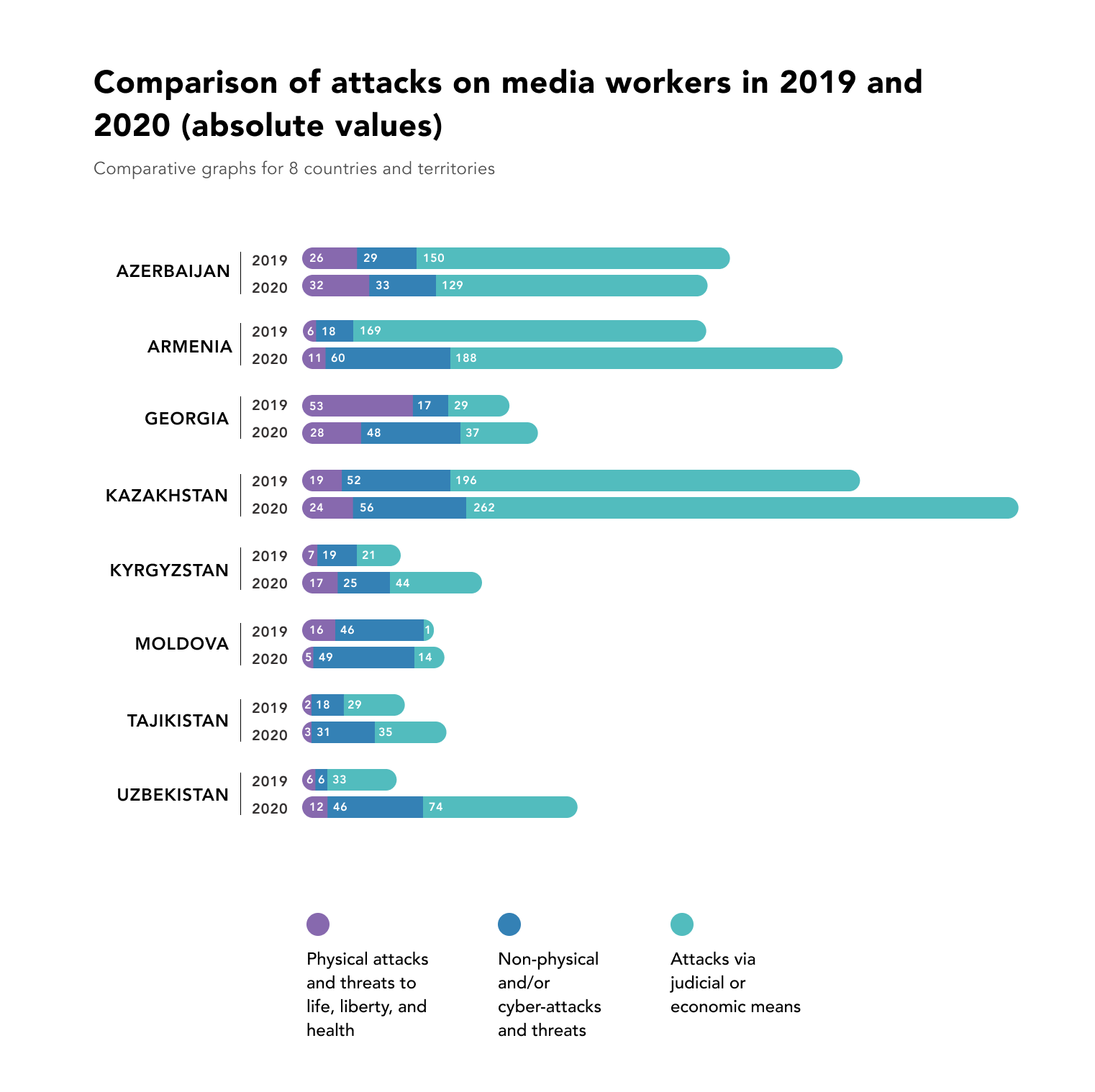

In all countries, except Azerbaijan, the number of attacks on media workers increased two and a half times in 2020 compared to 2019: from 1.907 to 4.611. The most notable increase was in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine.

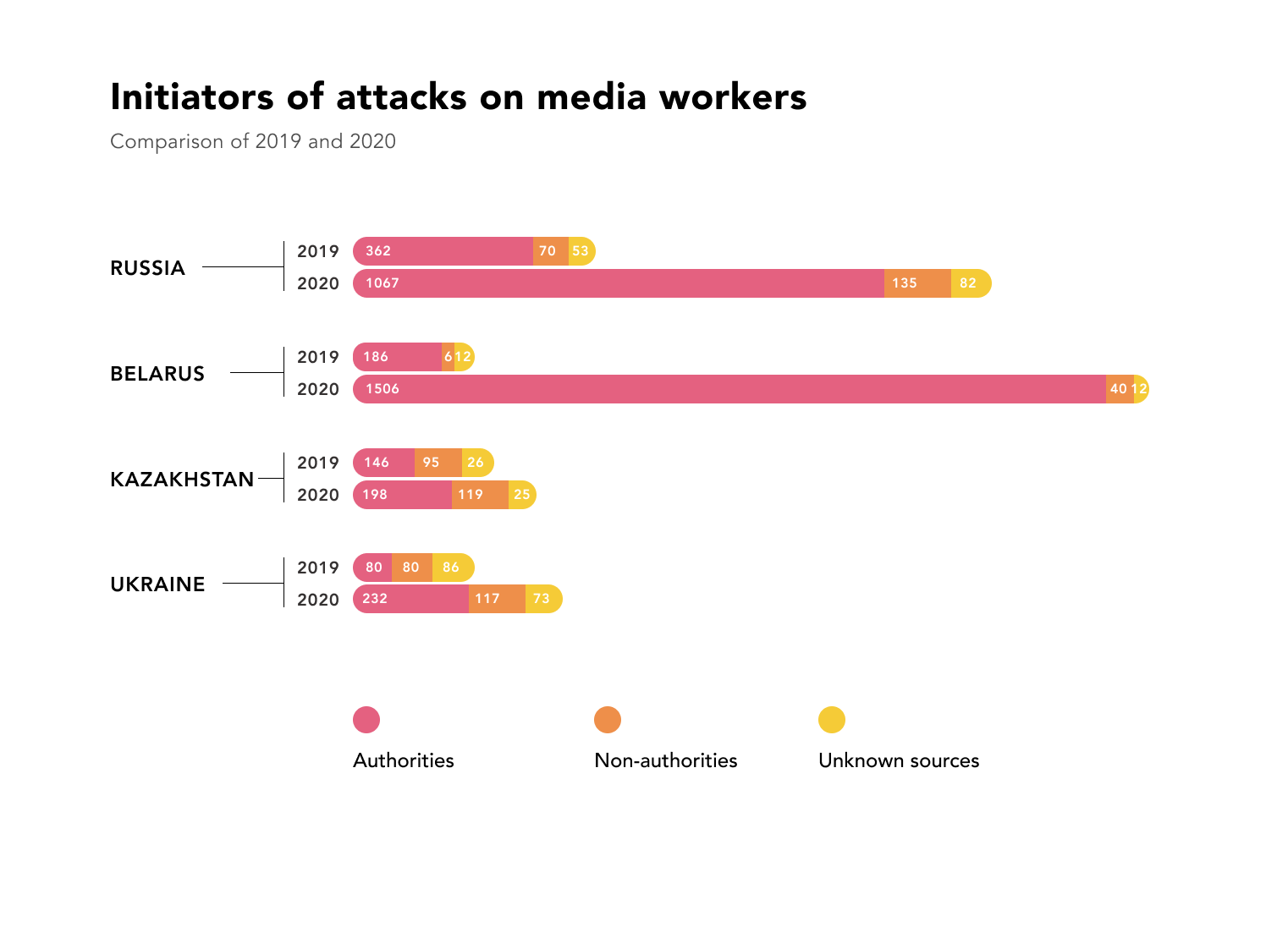

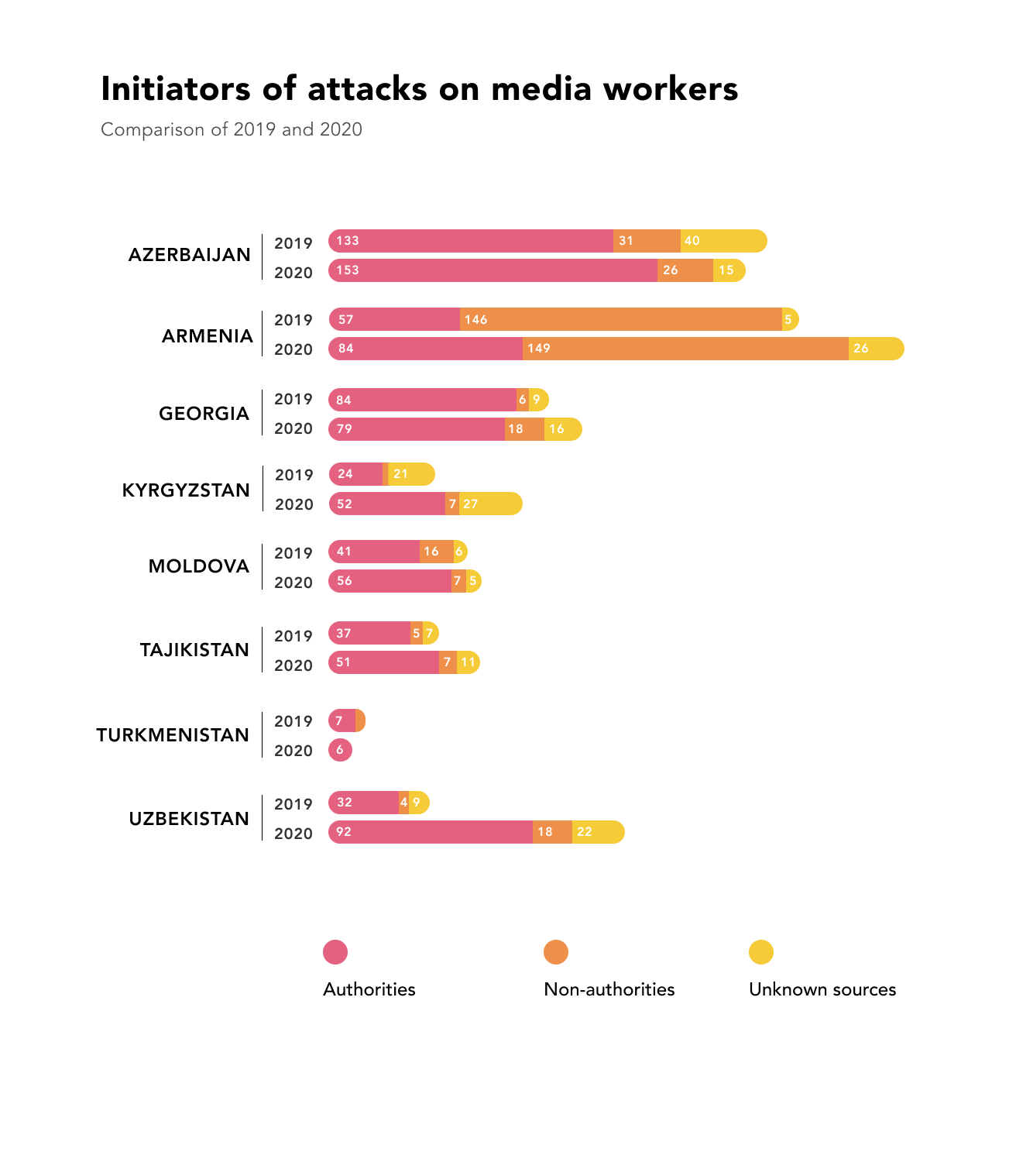

Representatives of authorities remain the main source of threats for media workers: in 57% of cases they are behind physical attacks, in 52% – non-physical and cyber-attacks and in 88% – attacks via judicial and economic means.

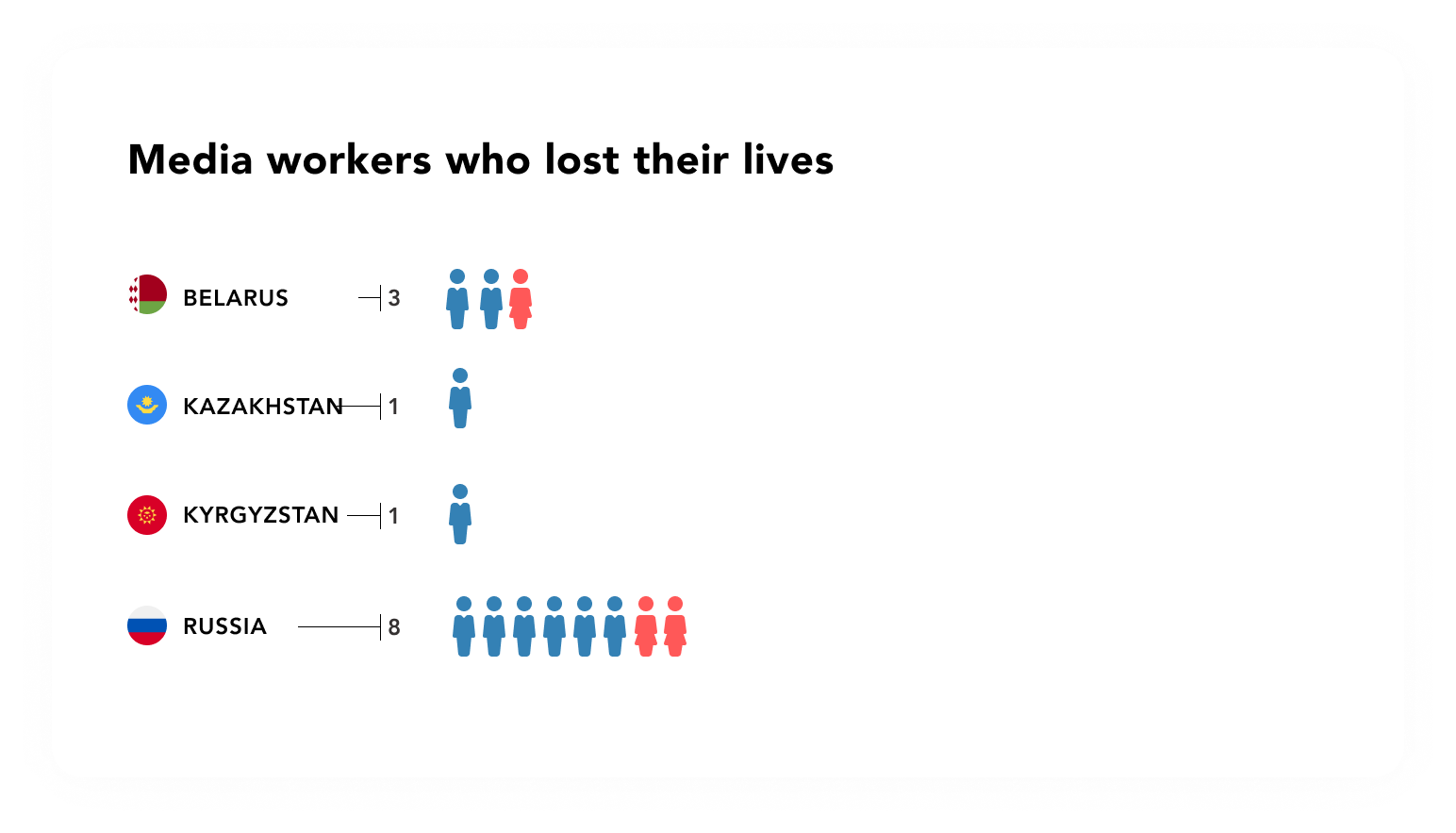

In 2020, 13 media workers lost their lives, which is almost double the figure from last year when 7 journalists lost their lives.

The main factors contributing to the deterioration of the environment for the journalists in the region were:

- New laws and regulations restricting media workers’ access to information and freedom of movement under the pretext of the COVID-19 pandemic and the fight against so called ‘fake news’;

- Protest activity and rallies against the worsening of the political, economic and social situation;

- New severe penalties for cooperation between local and foreign media and NGOs;

- The openly hostile attitude of some governments towards independent media.

For the purposes of representativity of the analysis, the 12 post-Soviet countries have been grouped based on their ratings in the Reporters Without Borders (RSF) Press Freedom Index for 2020.

Thus, the first group is composed of countries with rankings in the range from 160th to 180th place in the RSF index, in which the situation with freedom of the press is labelled as “very serious”. In the second group are countries ranked from 108th through 159th places; the situation in them is characterised as “difficult”. To the third group belong countries located between 49th and 107th place in the RSF index and described as “problematic”. Not one of the countries analysed by the Foundation falls in the group in which the situation is considered “good” or “satisfactory”.

Dividing into three groups allows us to compare the methods and sources of attacks in countries with similar rankings in the RSF Press Freedom Index.

KEY FINDINGS FOR GROUP 1 (VERY SERIOUS SITUATION)

| Place on RSF Index | Country | Population 2001 | Total attacks 2020 | Attacks per 100,000 (Risk Index) 2020 | Attacks per 100,000 (Risk Index) 2019 |

| 168 | Azerbaijan | 10,210,578 | 194 | 1.90 | 2.02 |

| 161 | Tajikistan | 9,717,772 | 69 | 0.71 | 0.51 |

| 179 | Turkmenistan | 6,104,827 | 6 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

Of the three countries found at the very bottom of the RSF Index and characterised as “very serious” for journalists, the most detailed monitoring of attacks is being conducted in Azerbaijan. Notwithstanding a slight drop in the overall number of attacks on media workers in this country, physical assaults have increased in frequency: their number grew by a factor of 5 in comparison with 2017. In 94% of the instances journalists are being beaten up with impunity by policemen, who likewise take or damage their equipment. In connection with the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the war in Nagorno-Karabakh (September – November), there was an intensification of harsh restrictive measures in relation to journalists: detentions, arrests, interrogations, searches, confiscations, and court trials. In 8 out of 10 instances, such attacks were initiated by representatives of the authorities. Seven journalists were being subjected to systematic attacks of a hybrid nature – they accounted for nearly a quarter of all the recorded facts of persecution of media workers in the country.

In Tajikistan, the number of attacks on media workers on the part of the authorities increased significantly. First and foremost this was connected with the parliamentary and presidential elections that took place in 2020. 3 physical attacks were recorded, two of them in relation to one particular journalist. Harassment of journalists living abroad intensified: state bodies were resorting to intimidation, defamation, and bullying in relation to them, as well as dissemination of their personal data and putting pressure on loved ones. The main judicial methods of pressure on media workers as a whole became a ban on entering the country, denial or revocation of a visa and/or accreditation, and shutting down a media outlet/blocking an internet site/request to remove or block articles, seizure of an entire print run.

In Turkmenistan, the situation with political and civil liberties continued to deteriorate. Citizens began to more actively express dissent with the policies of Berdimuhamedov’s regime, which led to an intensification of harsh repressive measures, both in relation to those whose work is directly associated with journalism and the dissemination of information, and against those who had reported on social media or though foreign media outlets about their personal problems or about arbitrary actions on the part of representatives of authority structures. A policeman beat up the 70 year old female journalist Soltan Achilova [Açylowa] whilst attempting to tear a camera out of her hands. Babajan Taganov [Taganow] was likewise beaten up in a police station as punishment for public statements made by his sister and mother residing in Turkey. The special services reduce all of the recorded instances of detentions and deprivation of liberty of citizens for their activity as reporters or for expressing an opinion to such articles of the Criminal Code of Turkmenistan as fraud or possession of the banned tobacco naswar or narcotics.

KEY FINDINGS FOR GROUP 2 (DIFFICULT SITUATION)

| Place on RSF Index | Country | Population 2001 | Total attacks 2020 | Attacks per 100,000 (Risk Index) 2020 | Attacks per 100,000 (Risk Index) 2019 |

| 153 | Belarus | 9,443,916 | 1558 | 16.50 | 2.16 |

| 157 | Kazakhstan | 18,961,941 | 343 | 1.81 | 1.42 |

| 149 | Russia (without Crimea) | 144,336,422 | 1284 | 0.88 | 0.35 |

| 156 | Uzbekistan | 33,865,670 | 132 | 0.39 | 0.13 |

In connection with the revolutionary events surrounding the elections of the president, Belarus became the record-holder for the amount and severity of cruelty of reprisals against media workers. The overall quantity of recorded attacks increased nearly 8 times compared to the previous year. Security personnel in the state service are the main danger for media workers in Belarus – it is specifically such individuals who are the perpetrators in 91 instances of beatings and torture. Belarus belongs to those countries that practice systematic attacks of a hybrid nature – the targets of 10% of all attacks were 13 journalists, whom the authorities were subjecting to a variety of different types of persecution throughout the course of the entire year. Most often it was representatives of Belsat, TUT.by, BelaPan, and Radio Liberty who suffered from the attacks of the authorities. The Foundation has recorded 513 instances of deprivation and restriction of liberty of media workers over this year.

Persecutions of media workers in Kazakhstan are implemented primarily with the help of judicial and economic means. In three quarters of the incidents it is representatives of the authorities who are standing behind such attacks. Things are particularly difficult for independent bloggers, online activists, and employees of Azattyq radio (Radio Liberty) – 12% of all attacks fell on them; their persecutions are of a hybrid nature. The number of physical threats and attacks has increased by a quarter over the last four years. The online activist Dulat Agadil [Ağadıl] died in a pre-trial detention facility in Nur-Sultan several hours after being detained. The blogger Aygul Utepova [Aigül Ötepova] and the online activist Asanli Suyunbayev [Asanälı Süieubaev] were forcibly hospitalised in specialised early treatment psychiatric clinics.

In Russia, the number of attacks on professional and citizen journalists in 2020 exceeded the total aggregate quantity of attacks for the three previous years by a factor of two. The increase took place primarily on account of attacks via judicial and economic means; moreover, in 93% of the incidents representatives of the authorities were responsible. 8 Russian journalists died this year, including Irina Slavina from Nizhny Novgorod who committed suicide as a result of many years of bullying, the opposition Chechen blogger Imran Aliyev was murdered in France, the blogger Mamikhan Umarov (“Anzor from Vienna”) was murdered in an Austrian suburb, and the Orenburg journalist Aleksandr Tolmachev, who died one month shy of release from a penal colony after a 9-year term.

There were more attacks/threats in relation to media workers recorded in Uzbekistan in 2020 than in the previous three years combined. 12 media workers and their relatives were subjected to physical assaults, 9 were arrested, and 46 were subjected to non-physical and cyber-attacks. The arrest in Kyrgyzstan and subsequent extradition to Uzbekistan of the journalist Bobomurod Abdullaev, who was in Bishkek in transit from Berlin, attracted considerable international attention. The journalist is being charged with assault on the constitutional order of the Republic of Uzbekistan and on the president. He has been prohibited from leaving Uzbekistan, and his movements inside the country are restricted.

KEY FINDINGS FOR GROUP 3 (PROBLEMATIC SITUATION)

| Place on RSF Index | Country | Population 2001 | Total attacks 2020 | Attacks per 100,000 (Risk Index) 2020 | Attacks per 100,000 (Risk Index) 2019 |

| 61 | Armenia | 2,967,406 | 259 | 8.73 | 6.51 |

| 60 | Georgia | 3,981,263 | 113 | 2.84 | 2.48 |

| 82 | Kyrgyzstan | 6,612,651 | 86 | 1.30 | 0.72 |

| 91 | Moldova | 4,025,573 | 68 | 1.69 | 1.56 |

| 97 | Ukraine | 43,506,666 | 422 | 0.97 | 0.56 |

In Armenia, the number of violations of the rights of journalists and media outlets grew by a third, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, an all-out war in Nagorno-Karabakh, and the exacerbation of the socio-political situation in the post-war period. Physical attacks on journalists were committed mainly during coverage of mass protests. The number of victims doubled in comparison with the previous year. The predominant method of pressure on media workers remained lawsuits with charges of insult and libel – 79 court cases were initiated over the year.

The number of assaults on media workers in Kyrgyzstan nearly doubled. A record quantity of beatings of journalists was recorded because of the after-effects of the third revolution, while many media outlets’ editorial offices were subjected to assaults against the background of raider captures of ownership; a record number of journalists were interrogated; a law was adopted in the country allowing the authorities to demand the deleting of “unreliable” information without a court sanction. The journalist Azimzhan Askarov, who had been in detention for more than 10 years, died in prison. He was accused of inciting inter-ethnic discord and killing a policeman during ethnic violence in southern Kyrgyzstan in 2010. The United Nations Human Rights Committee had previously found Askarov a victim of torture and all court decisions in his criminal case to be unjust.

The majority of attacks on media workers in Georgia were related to the parliamentary elections of 31 October. 16 of the 26 physical attacks recorded in 2020 were implemented by representatives of the authorities; a large part of the journalists suffered from tear gas poisoning and the use of water cannons (dousing with water containing chemical reagents) on the night of 9 November outside the Central Electoral Commission building. The government’s main targets were television channels of an opposition orientation – Mtavari Arkhi, Formula, and Priveli, as well as employees of the Public Broadcaster of the Adjaran Autonomy who had spoken out against the channel’s pro-government policy. Non-physical attacks predominated in the country, above all damage to/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials.

The quantity of attacks via judicial means, above all by means of charges of libel, insult, reputational damage, grew sharply in Moldova in 2020. The main source of non-physical attacks/threats in relation to media workers were representatives of the authorities, including politicians, parliamentary deputies, president of the Republic of Moldova Igor Dodon (until 15 November 2020), and other persons holding public office at the central and local/regional levels. Of the five physical attacks on journalists recorded in 2020, four were carried out by employees of the State Protection and Guard Service, policemen, and Russian military deployed in Transnistria.

The most widespread method of pressure on media workers in Ukraine remains non-physical attacks, above all illegal impediments to journalistic activity and denial of access to information. Popular ways of intimidating and exacting revenge on journalists remain arson or damage to their dwellings and automobiles. The number of physical assaults on media workers increased by 19% in comparison with the previous year, but, unlike in the other countries of the region, in Ukraine representatives of state structures played the role of aggressors in only one incident out of every three.

RISK REDUCTION MECHANISMS

Analysis of the types of media risks, as well as of their geography, frequency, and sources, is a necessary condition for working out ways of protection and being prepared. It is not realistic to keep track of all attacks on media employees. Nevertheless, analysis of the data that has been obtained allows us to offer several recommendations for how to most effectively counter attacks in each of the groups of countries.

Group 1 and Belarus

The life and work of a journalist in these countries is turning into a never-ending struggle for survival in a hostile environment. International laws and moral constraints in relation to journalists and bloggers do not work; it is therefore impossible to protect oneself systemically from the attacks of the authorities – and it is precisely they who stand behind the majority of assaults. Journalists from these countries working abroad absolutely must:

- secure the safety of their loved ones residing in the country;

- take precautionary measures when moving about or travelling, be aware of suspicious persons and items, be in constant contact with the police of the countries where they have received a residence permit or asylum;

- as much as possible, keep track of their digital security; create backup copies of data, materials, and documents and store them in secure places because the risks of destruction of equipment and seizure of written, audio, and video materials are extremely high;

- not forget about their emotional and mental health – burnout and PTSD often accompany work in such inhuman conditions.

For those journalists who continue to live and work inside these countries, the methods of protection should be the same as if they were working in a hot spot, covering terrorist attacks or combat operations.

It is pointless to even discuss the judicial security of journalists as often times these are countries where rule of law is absent and laws and directives that are ever more hostile to independent journalism and civil society are constantly being adopted.

The work of truthfully covering what is happening in these countries is impossible without help from beyond the border; it is therefore imperative to ensure secure channels of communication. Besides that, independent media workers must have stable financial support in order to pay fines for working with foreign media outlets. In the event that foreign channels or contacts have been compromised, it is imperative to have a plan for evacuation from the country or for other actions that will allow them to get out of the sphere of attention of the state’s repressive services.

Group 2

If the political situation in these countries does not improve, media workers there are going to end up in the same situation as their colleagues from Group 1 and Belarus. In this case, it will not be long before they are going to find themselves having to choose among three options – to leave the profession, to leave the country, or to change jobs and go to work in propaganda structures connected with the state. It is senseless to wait for protection from the police and nearly impossible to attain justice in courts in Group 2 countries, because these bodies are an integral part of a single repressive system aimed at suppressing any dissident thought and independence. However, as long as media workers in these countries are finding an opportunity to tell their audience the truth, it is imperative that they observe the following rules at a minimum:

- minimise opportunities for an assault on themselves on the part of unknown persons or law-enforcement and security agencies, not walk alone, maintain constant contact with trusted people, reporting via secure channels about their plans and whereabouts, wear maximally protective clothing and footwear when working at events with high physical risks.

- create backup copies of data, materials, and documents and store them in secure places because the risks of destruction of equipment and the seizure of written, audio, and video materials are high; take verbal and telephone threats and cyber-attacks seriously, informing the security services of their media organisations and the police about them.

- know their rights, keep abreast of new legislation in the media sphere and the latest instances of judicial attacks on media workers; have all the documents and identifying markings required by current legislation with them when carrying out editorial assignments; comply to the extent possible with all directives in relation to events attended in a professional capacity; always have a valid agreement with a lawyer and a power of attorney to represent their interests.

- Not to forget about their mental health – emotional burnout and PTSD often accompany work in such difficult conditions.

Group 3

Media workers in this group of countries find themselves in a situation that is dangerous but not catastrophic. In connection with political perturbations and civic protests journalists are not infrequently subjected to physical risks, which can be minimised by observing security measures for journalists when covering mass events.

The most realistic threat for journalists in this region is non-physical and cyber-attacks and threats. To minimise the risks, it is imperative for them to create backup copies of data, materials, and documents and store them in secure places because the risks of destruction of equipment and the seizure of written, audio, and video materials are high; take verbal and telephone threats and cyber-attacks seriously, informing the security services of their media organisations and the police about them.

Close cooperation between media workers, above all investigative journalists who bring up corruption and other hard-hitting political topics, and human rights non-profits and structures offering legal counsel would appear to be an effective measure of protection from non-physical and judicial attacks. In situations when journalists are being accused of libel and insults, publicity is important, because a public reaction often helps reduce assaulters’ enthusiasm and protects media workers from bullying and harassment.

ANNEX 1: ATTACK TYPES, IDENTIFIED BY JFJ FOUNDATION

Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health

- Abduction, taking captivity/hostage, illegal deprivation of liberty

- Attempted murder

- Beating / injury / torture resulting in death

- Death while in custody or as a result of loss of health in captivity

- Disappearance

- Fatal accident

- Murder

- Non-fatal accident

- Non-fatal attack / beating / injury / torture

- Pressure on a media worker via physical pressure on relatives and loved ones

- Punitive psychiatric treatment not resulting in death

- Punitive psychiatric treatment resulting in death

- Sexual harassment

- Sexual violence

- Sudden unexplained death

- Suicide

- Suicide attempt

- Unlawful military conscription

Non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats

- Breaking into email / social media accounts / computer / smartphone

- Bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber-

- Cyber-, DDOS, and hacker attack on a media outlet

- Damage to / seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials, print run

- Damage to/seizure of the residence/work premises

- Defamation, spreading libel about a media worker or media outlet

- Identity theft / phishing / doxxing

- Illegal impediments to journalistic activity, denial of access to information

- Pressure on a media worker via non-physical pressure on relatives and loved ones

- Pressure on a source, including threats of violence and death

- Trolling

- Wiretapping/surveillance without a court decree

Attacks via judicial or economic means

- Administrative arrest, remand, pre-trial detention, prison

- Administrative offence / fine

- Arrest of bank account

- Authorised travel ban (movement inside a country or specific region/town)

- Ban on engaging in journalistic activity

- Ban on entering the country, denial or revocation of a visa/accreditation

- Ban on leaving the country

- Charges of dissemination of false information (3)

- Charges of extremism, links with terrorists, inciting hate, high treason, calling for the overthrow of the constitutional order, rehabilitation of Nazism (2)

- Charges of libel, insult, reputational damage (1)

- Confiscation/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials

- Court trial

- Criminal/administrative case, excluding (1), (2) and (3)

- Dismissal / involuntary dismissal /forced quitting of the profession

- Forced deportation, Extradition

- Forced emigration as a result of legal/economic pressure

- House arrest

- Interrogation, questioning

- Designation of foreign agent status and/or judicial prosecution for non-compliance with the law on “foreign agents”

- Pressure on a media worker via judicial and/or economic means on relatives and loved ones

- Punishment in a criminal case without deprivation of liberty (community service, compensation for moral damage and etc.)

- Search with a court decree

- Search without a court decree

- Selective application of repressive laws

- Short-term detention

- Shutting down a media outlet / blocking an Internet site/ request to remove or block articles, seizure of an entire print run

- Suspended sentence

- Unauthorised travel ban (inside country, region or town)

- Wiretapping/ surveillance with a court decree