AZERBAIJAN

An independent expert opinion about Attacks on media workers in Azerbaijan report

Azerbaijani media lives through one of the most difficult periods in its history. Apart from individual attacks on government critics, the lack of institutional support mechanisms and access to free and fair judiciary have affected its ability to cover news professionally and effectively.

Figures talk for themselves. There is no single opposition or independent print media left in the country. TV channels are heavily controlled and viewers don’t recall the last time they have seen or heard any opposition member on TV or radio. Opposition uses internet media to reach out to viewers, but those who provide them airtime are subject to cyber and physical attacks by the government, as described in the report.

The non-government organizations who used to support journalists by representing them in the courts, providing legal and technical assistance are banned in Azerbaijan, leaders of the NGOs had been subject to arrests, freezing of bank accounts, travel bans.

The independent and pro-opposition websites are blocked with and without court orders, cyber-attacks prevent their outreach, while reporters, editors and their family members become targets of despicable blackmailing and harassment campaigns.

Most of the local reporters who work for media outlets and are based in foreign countries for safety reasons, have been pushed to work anonymously as the government prosecutes cooperation with foreign media without accreditation. Accreditation is supposed to be provided by Foreign Ministry, which simply does not respond to the letters.

Bloggers and journalists who uncover corruption of government officials lack institutional support and the market for their reporting and resources, while being subjected to surveillance, which also makes it difficult to ensure safety of whistleblowers and information sources.

Access to information is more difficult than ever, as the government provides access to officials and documents only to controlled media. The journalists lack resources to file freedom of information lawsuits, while lawyers who defend journalists in the courts are subject to disbarment and attacks by government-controlled Bar Association. Government endorses attacks against critics in controlled media, awarding those who play active role in smearing bloggers and journalists.

Electronic and physical surveillance by state security services is an ongoing problem, and as a result, personal information and private lives of journalists are often exposed in government controlled media.

Social media users who criticize police and the president are punished with administrative arrests, arbitrary detentions and physical violence. Large-scale troll attacks on government critics are also frequent and are evidently directed by the ruling party.

Situation with the media freedom in Azerbaijan is dire but not hopeless. Despite all the difficulties the profession still attracts young generation who seek to boost their capacity in limited number of training projects.

Khadija Ismayilova

Investigative journalist and trainer

Author of the report – Khaled Aghaly, lawyer and specialist in media law in Azerbaijan.

1/ KEY FINDINGS

194 instances of attacks/threats in relation to professional and citizen media workers and editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Azerbaijan in 2020 were identified and analysed in the course of the research. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Azerbaijani, and English languages using the method of content analysis. Likewise used were expert interviews of journalists who had been subjected to assault, and of their lawyers. A list of the main sources is presented in the Annex 2.

- The quantity of attacks on journalists and media workers in 2020 in comparison with 2019 remained at the same level — the difference comprises just 5.4%.

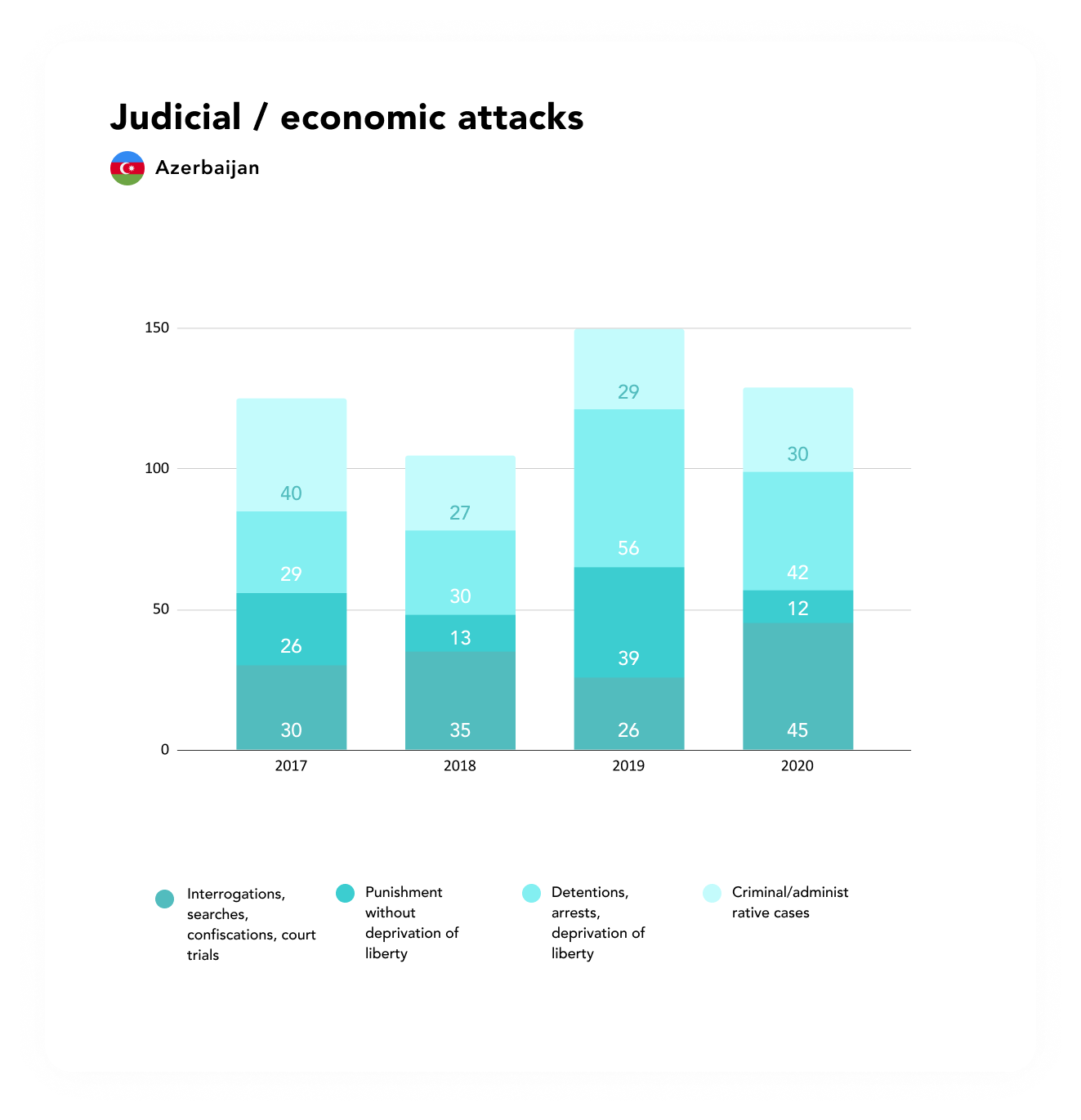

- As before, the main method of pressure on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in Azerbaijan is attacks via judicial and/or economic means. Court trials and short-term detentions predominate.

- Parliamentary elections took place in Azerbaijan in February. Journalists working at protest events after the elections were subjected to physical pressure on the part of representatives of the authorities.

- Representatives of the authorities actively used quarantine restrictions and the war in Karabakh to infringe on freedom of speech and create obstacles for journalists.

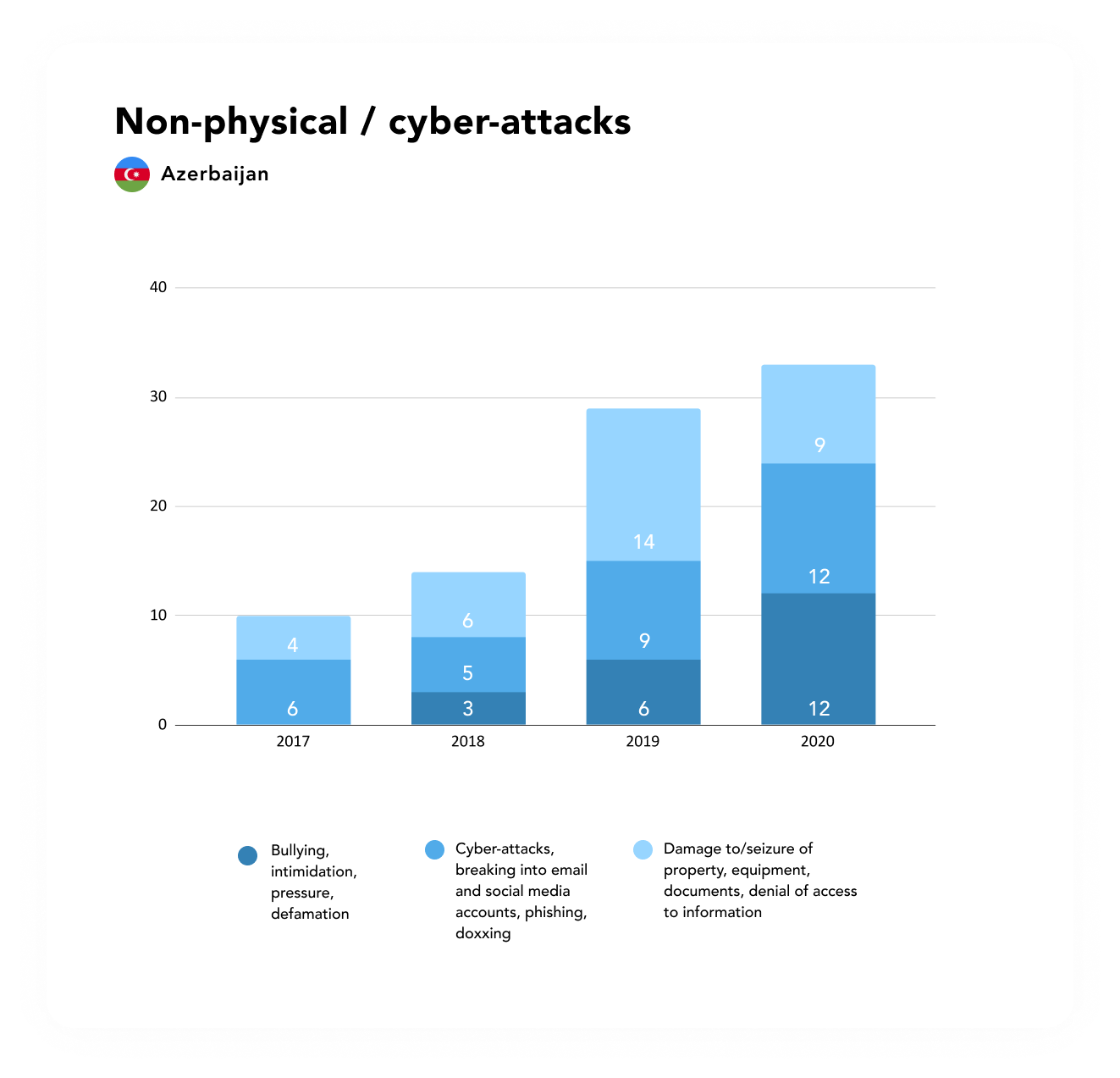

- The main method of non-physical pressure was cyber-attacks against the websites of independent media outlets. There were 10 such incidents recorded in 2020.

Attacks on journalists associated with the war in Nagorno-Karabakh were not included in the present report.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN AZERBAIJAN

According to the annual reports by Reporters Without Borders, the situation with freedom of the media in Azerbaijan continues to deteriorate. In 2020 the country took 168th place in the worldwide rating, having dropped by five places in two years.

According to the Freedom on the Net report for 2020 drawn up by Freedom House, internet freedom is absent in Azerbaijan– the country garnered 38 out of 100 points. As recently as 2017 the internet in Azerbaijan was considered “partly free” (42 out of 100 points). Freedom House associates the absence of internet freedom with low connection quality, control of the information and communications technologies sector, manipulation of the information space by the state, and blocking of resources on which news unfavourable to the government is posted.

The quantity of mass information media registered in Azerbaijan according to the official data exceeds 5000. In reality there are significantly fewer functioning media outlets and other media structures: there are around 50 news agencies, 300 news and analysis websites, and around 300 newspapers and magazines.

There is an operating Press Council, which was founded as a public association. However this structure is in fact under the government’s control. Besides that, in Azerbaijan there is a Fund for State Support of Mass Information Media, which supports the print media. This fund was created by the state and is funded by it. Print media depend on annual state subsidies. The Fund likewise builds houses for journalists, furnishing them with free housing.

94 television and radio broadcasters function in the territory of Azerbaijan: 12 nationwide and 12 regional television broadcasters, 16 radio broadcasters, 3 satellite television operators, 17 cable network operators, 32 IPTV operators, and 2 operators of satellite broadcasting of foreign television channels. The sphere of television and radio broadcasting is regulated by the National Council for Television and Radio – a state structure. Funds are periodically allocated to the Council from the state budget to be distributed among the television and radio broadcasters.

Print and broadcast (television and radio) media outlets are practically completely controlled by the state. These media outlets depend primarily on state subsidies. The overall volume of the media outlet advertising market in the country comprises 5-6 million dollars. This indicator is tens of times smaller than in neighbouring countries. Inasmuch as business is under political control, the media outlets are deprived of their main source of income – advertisement.

Internet media outlets are to a significant degree free from the government’s control. However, independent internet media outlets likewise do not receive sufficient income from advertisement. They are funded in the main on account of grants from donor organisations. In recent years the government is coming out with initiatives in the realm of regulating internet media outlets.

Analysis of the data gathered shows that the methods of intimidating media workers in Azerbaijan have remained the same as before:

- Subjected to physical and non-physical pressure, as a rule, are independent media outlets that criticise the government and journalists working for such media outlets

- Independent and opposition journalists and bloggers are detained by law-enforcement agency employees, and their professional equipment is confiscated or damaged.

- Journalists in relation to whom a criminal case has been initiated are as a rule held in custody before trial.

- Journalists are subjected to physical pressure, and are often beaten; the legal mechanisms to protect journalists from brutal physical pressure do not work.

- Journalists and media outlets are frequently criminally and civilly sued for libel and insults; judicial practice in this realm totally does not correspond to the practice of the European Court of Human Rights.

- The blocking of internet media has become an everyday occurrence; the country’s parliament has introduced norms into legislation to facilitate blocking.

- Media outlets publishing materials that the government does not like are subjected to cyber-attacks.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

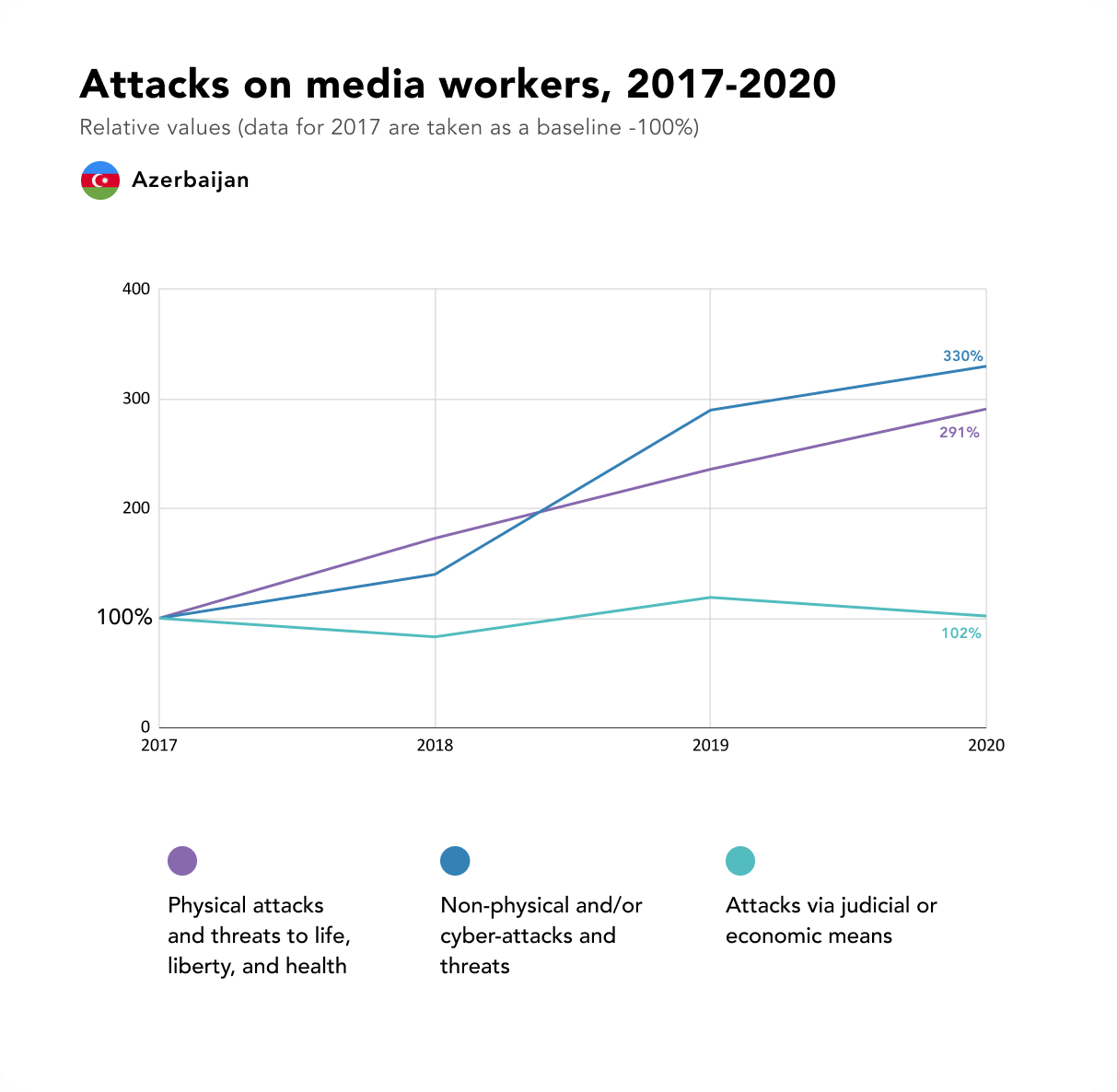

The following graph presents the overall quantity of attacks on journalists, bloggers, and other media workers in Azerbaijan from January 2017 through December 2020. In comparison with 2019, the quantity of attacks in 2020 remained at nearly the same level, having gone down by just 5%.

The number of physical attacks and non-physical and/or cyber-threats remained at just about the 2019 level, having increased slightly. Attacks via judicial and/or economic means continue to remain the predominant method of pressure by the authorities on media workers. However, in comparison with 2019 their quantity shrank by 8%.

It should also be taken into account that harsh restrictive measures were applied in relation to journalists in 2020 in Azerbaijan in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the war in Nagorno-Karabakh (September-November).

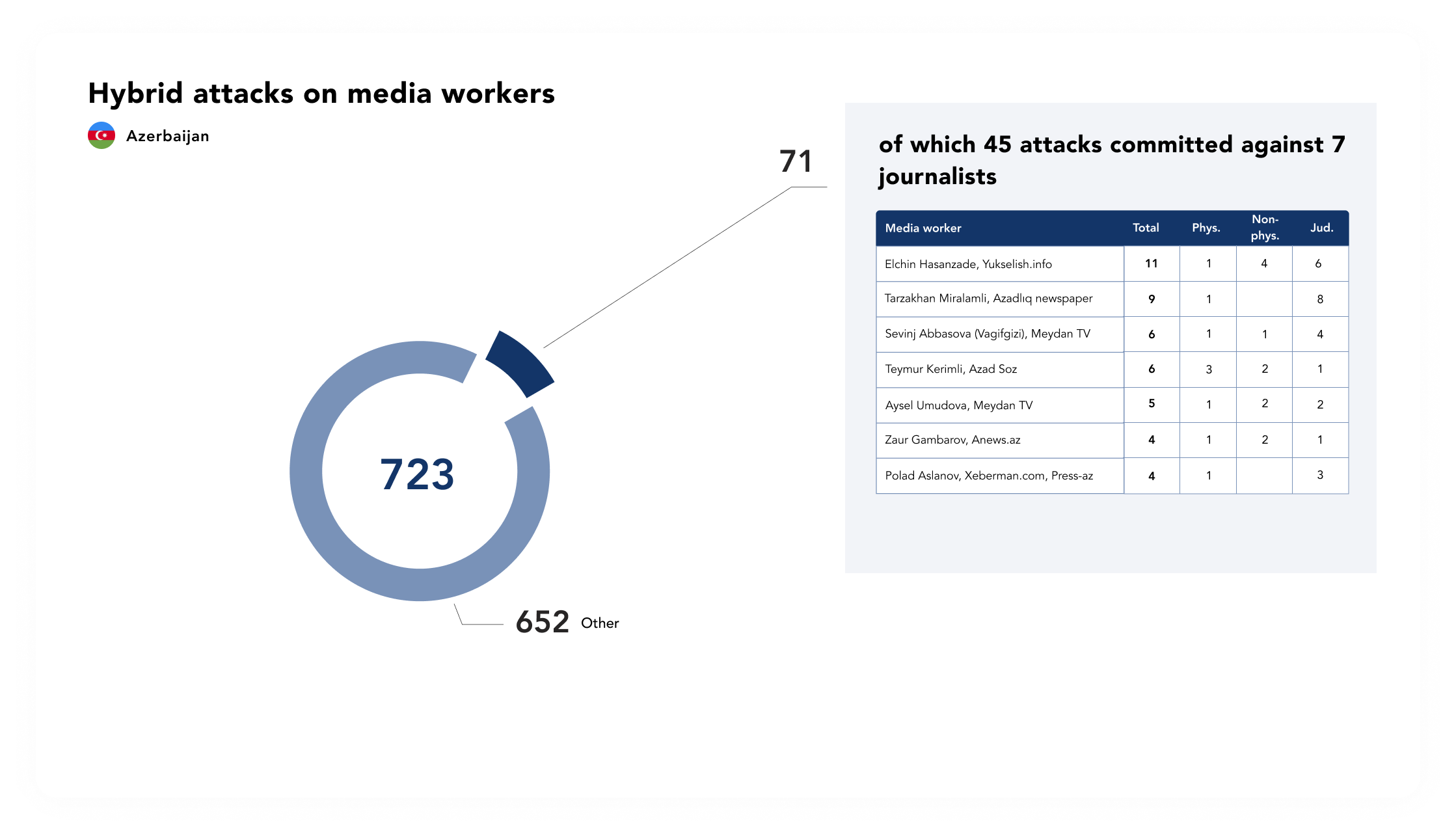

For the purposes of more precisely reflecting combination assaults on media workers in 2020 we are introducing a new category of attacks – hybrid.

We are calling systematic persecution of some publication or media worker with the use of tools from two or more categories of assaults – physical, non-physical, and judicial/economic – “hybrid”. Such a combination of means involving and not involving force with judicial means of pressure on undesirable journalists is carried out with a view to demoralising them or getting them to self-censor or to give up the profession or even life itself.

Presented below is the list of the journalists and bloggers who were being subjected to the most intensive hybrid attacks in 2020.

4/ PRESSURE ON JOURNALISTS UNDER THE PRETEXT OF RESTRICTIONS CONNECTED WITH THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The restrictions introduced in Azerbaijan in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic created additional problems for the media. Strict quarantine restrictions and rules came into effect as of March 2020 in connection with the pandemic. Their legitimacy was disputable: the country’s legislation does allow for the application of such harsh measures in the event of the introduction of a state of emergency; a state of emergency was not declared, however.

At the first stage of quarantine measures, which extended until the end of May, only persons who possessed press cards could freely implement journalistic activity. Journalists, bloggers, and photo reporters who were not on the staff of a media outlet were factually deprived of the opportunity to work freely. A system of text-message permissions for leaving home for a period of 2 hours was introduced across the country. Freelance journalists had to restrict themselves to these time constraints.

The second stage of tightening quarantine measures began in June: of all journalists, only state television employees were permitted to work. These restrictions were gradually softened. Journalists registered in the state system of permissions could work freely. The restrictions remained in effect in relation to freelance journalists who were not registered, however.

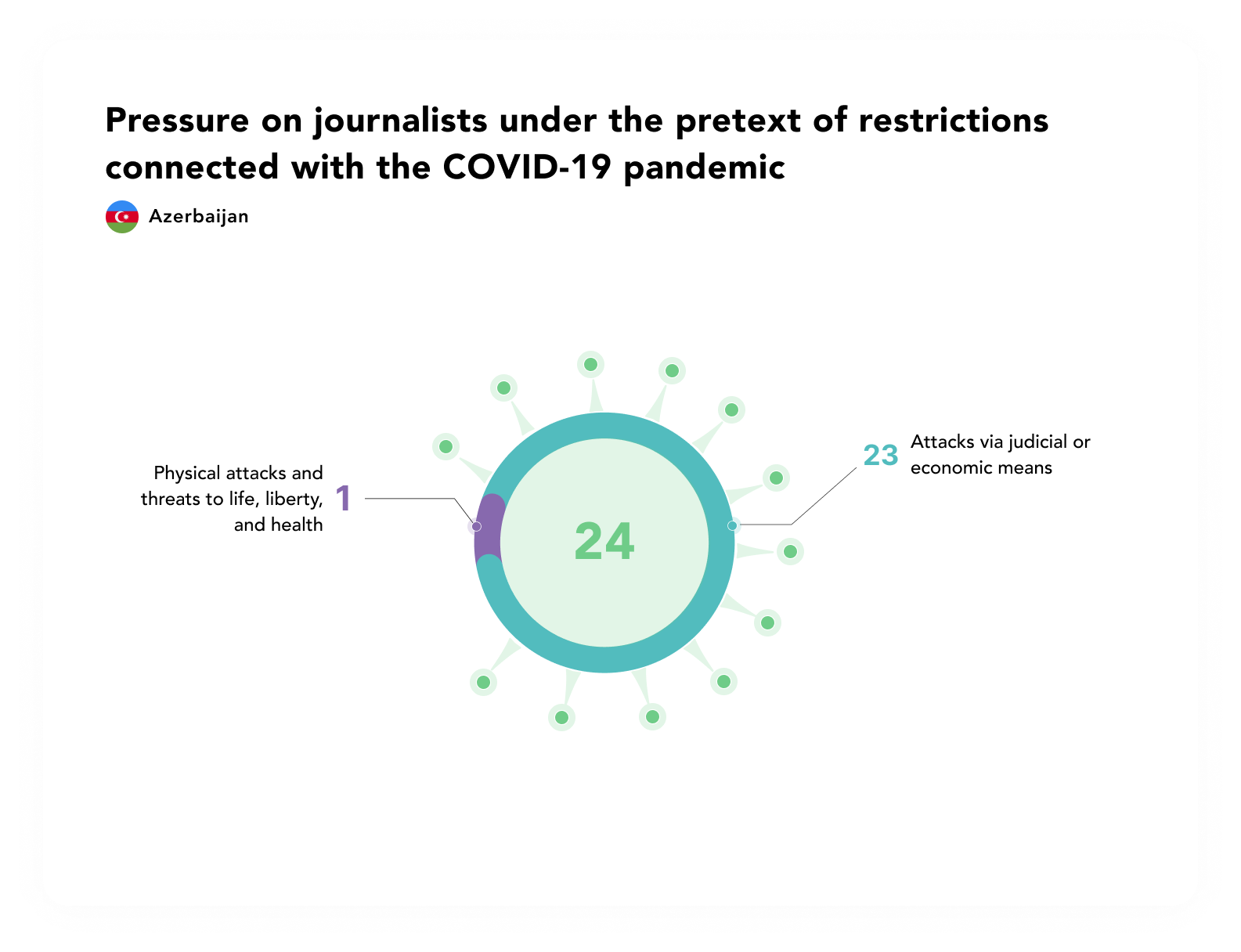

There are 24 incidents connected with quarantine restrictions recorded on the Media Risk Map. In all cases but one, what is being referred to is attacks via judicial and/or economic means:

- On 9 April, 7gun.az news portal employee Natig Isbatov [Natiq İsbatov] was detained whilst executing professional duties and taken to the police. The next day a court found him guilty and gave him 30 days of administrative arrest. Detained together with Isbatov was azel.tv news portal employee Sevinj Sadigova [Sevinc Sadıqova]. After an official warning she was released.

- On 12 April online television channel Kanal24 employee Ibrahim Vazirov [İbrahim Vəzirov] was taken to the police administration of the Shivran [Şirvan] District for violating the quarantine regime. Vazirov was found guilty of insubordination to the police. The court gave him 25 days of administrative arrest.

- On 14 April, online television channel Doğru TV employee Mirsahib Rahiloglu [Rahiloğlu] was delivered to the police administration of Shivran District for violating the quarantine regime. They found Rahiloglu guilty of insubordination to the police and sentenced him to 20 days of administrative arrest.

- On 21 April, freelance journalist Elgun Ganjimsoy [Elgün Gəncimsoy], writing about the military, was detained by employees of the Agdam [Ağdam] District administration of the police. They charged him with violating the rules of quarantine despite the fact that he produced a journalist’s identification document. A court found the journalist guilty of violating the quarantine regime and of resisting the police. Ganjimsoy was arrested for 20 days.

- On 22 April, journalist Ismail Islamoglu [İsmayıl İslamoğlu] was detained by police employees in the Shivran District. The journalist produced a press card but was nonetheless charged with violating the rules of quarantine. A court sentenced him to 25 days of administrative arrest.

- On 28 April, at around 12 pm, opposition newspaper Azadlıq (azadlıq.info) employee Saadat Jahangirgizi [Səadət Cahangirqızı] was detained outside the entranceway to the building where the leader of the Azerbaijani Popular Front opposition party Ali Karimli [Əli Kərimli] resides. The journalist was held in the police station until four o’clock in the afternoon and was given a fine of 100 manats for violating the quarantine regime despite the fact that Jahangirgizi showed a journalist’s identification document.

- On 1 June, police employees detained independent journalist Vugar Mirzabek [Vüqar Mirzəbəyev] at a student protest rally outside the Ministry of Education. He was fined in administrative order for violating quarantine rules.

- On 2 July, blogger Fatima Movlamli [Fatimə Mövlamlı] was fined for violating the rules of quarantine. Policemen detained Movlamli on the way to work. She produced a press card but was still fined 200 manats.

- Blogger Ibrahim Turksoy [İbrahim Türksoy] disappeared on 15 July. In the course of five days, his whereabouts were unknown, after which his loved ones ascertained that the blogger had been arrested for 15 days for violating the rules of quarantine.

One incident associated with physical pressure took place on 16 May. A case of coronavirus infection was documented in penal colony number 17, and a quarantine regime was declared in the institution. It is being reported that Azadlıq newspaper employee Elchin Ismayilli [Elçin Ismayıllı] was locked up in solitary confinement for five days under the pretext that he supposedly was not wearing a mask. In actuality, Ismayilli had been punished for criticising the sanitary measures adopted by the colony’s management personnel.

5/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

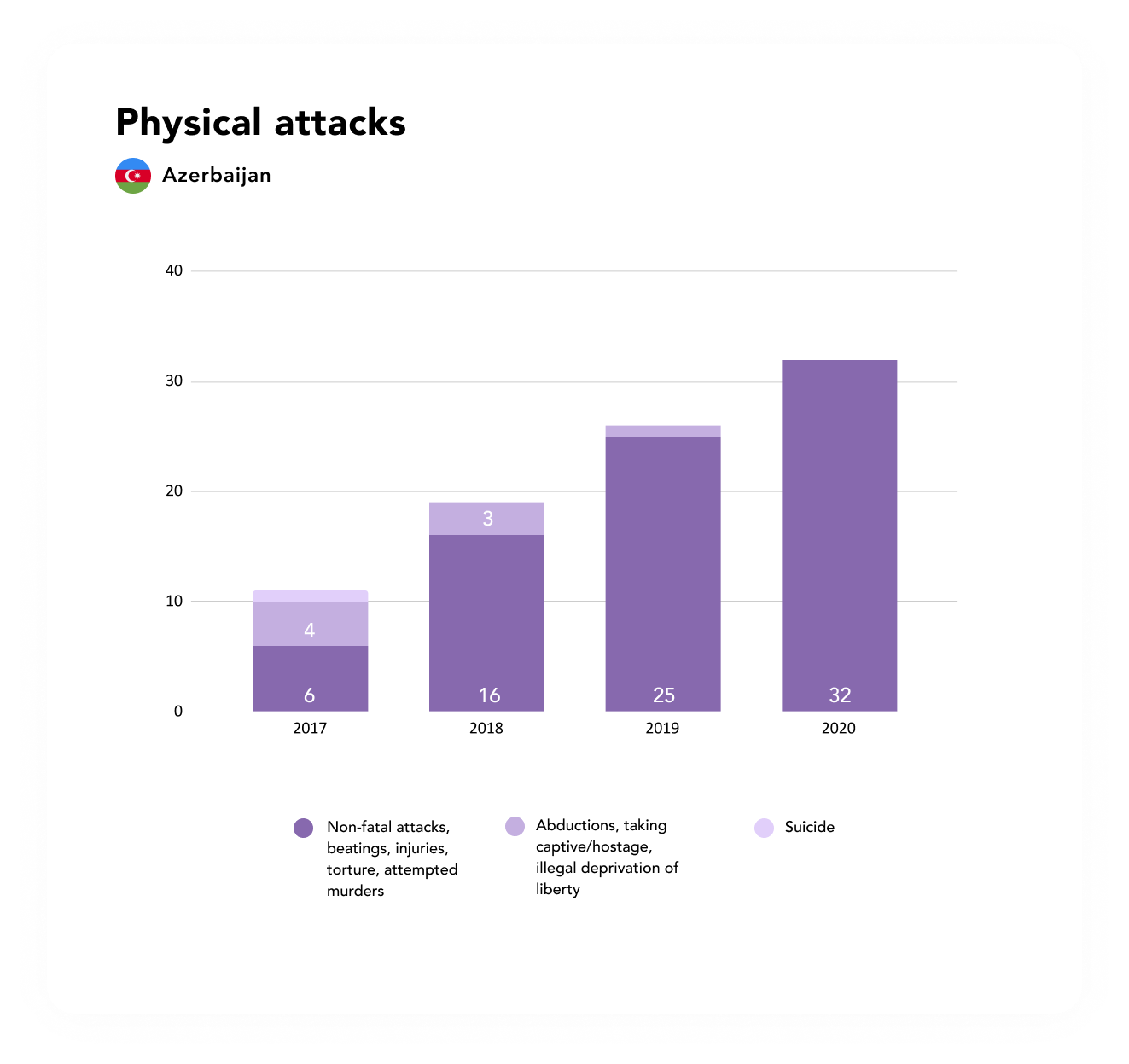

In 2020, journalists and media workers were subjected to physical pressure no fewer than 32 times. All of the recorded incidents belong to the category of non-fatal attacks/beatings/injury/torture.

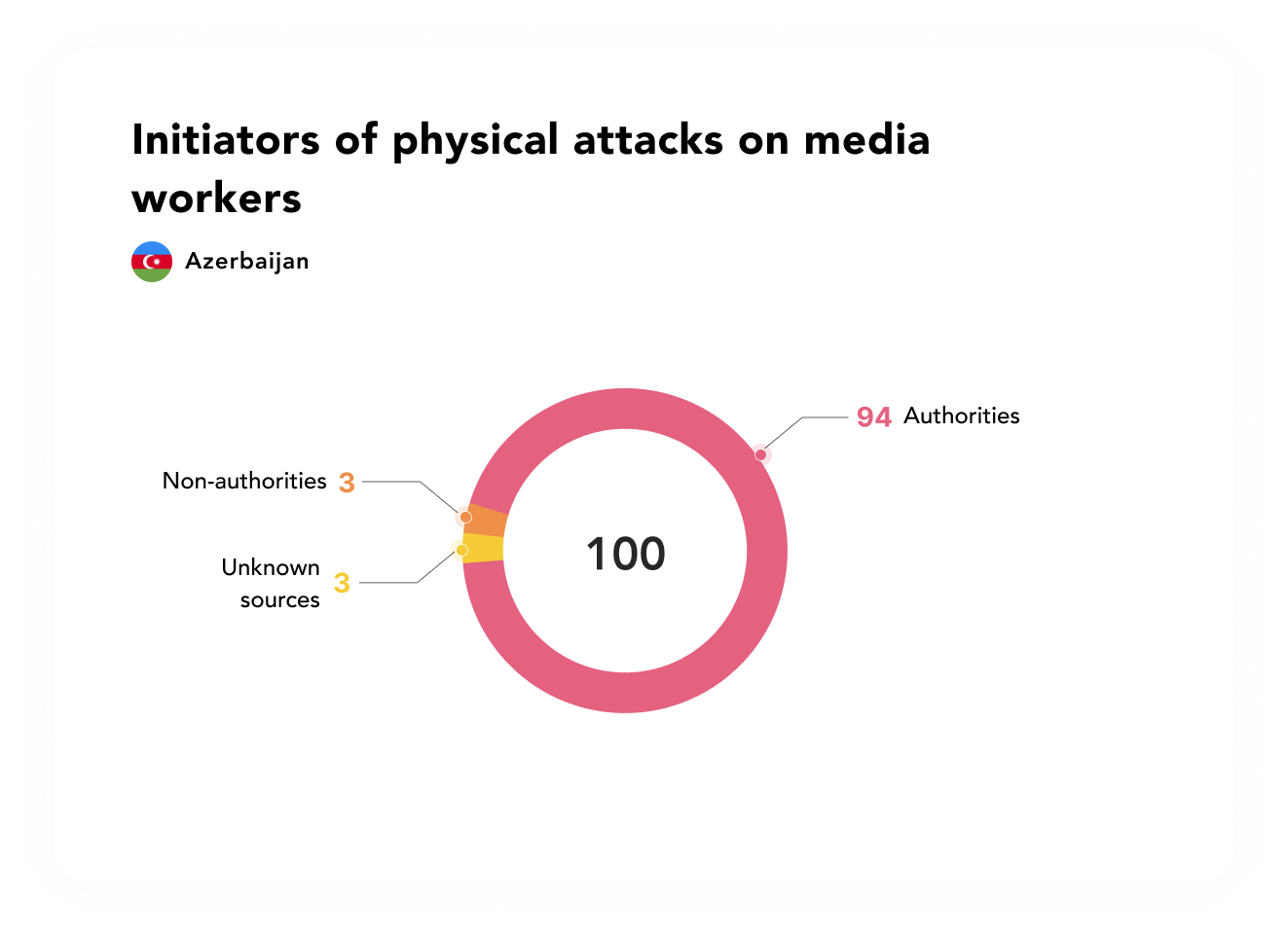

In 30 of the incidents, the physical attacks came from representatives of the authorities. Most often such incidents took place as journalists were working at mass gatherings or protests. Nearly all the journalists who encountered physical pressure were representatives of independent media outlets.

Parliamentary elections took place in Azerbaijan in February. Journalists covering the protests after the elections were subjected to pressure. The majority of the journalists gathering information about the rally outside the Central Electoral Commission building at the beginning of February had obstacles put up in their way, while in some cases force was used against them.

- On 6 February, at a meeting with voters by the candidate for deputy [MP] Aydin Mirzazade [AydınMirzəzadə] in the city of Mingachevir [Mingəçevir], journalist Elchin Hasanzade [Elçin Həsənzadə] was not allowed to make an audio recording or conduct a video shoot. Hasanzade was detained with the use of force.

- On 11 February, editor of the Basta.info website Mustafa Hajibeyli [Hacıbəyli] was cruelly beaten by policemen. They detained him during dispersal of a protest rally in front of the CEC building against falsification of the results of the parliamentary elections. On that same day the Meydan TV journalists Aynur Elgunesh [Elgünəş], Aytaj Taptyg [Aytac Tapdıq], and Sevinj Abbasova (Vagifgizi) [Sevinc Abbasova (Vəqifqızı)], as well as investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova [Xədicə İsmayılova], were detained and violently beaten by the police, receiving physical injuries.

Physical attacks on journalists were committed during the time of other protests as well.

- A march against violence against women took place on 8 March in Baku. Journalists working at the event were subjected to assaults by policemen. Meydan TV employee Izolda Agayeva [İzolda Ağayeva] received a scratch on the throat as the result of police interference. Meydan TV journalist Aysel Umudova, shooting video of the detaining of participants in the march, was herself detained for several hours. In the police station representatives of the authorities demanded that she erase the video recording. Toplum TVjournalist Zarifa [Zərifə] Novruz was hit on the arm, as a result of which her telephone fell and broke. Her press card was torn up. Likewise subjected to pressure were correspondents from the Turan agency Aziz Kerimov [Əziz Kərimov] and Tatiana Kryuchkina, Fargana Novruzova [Fərqanə Novruzova] (azadliq.info), Nargiz [Nərgiz] Abdsalamova (Mikroskop Media), and Samirа Ali [Samirə Əli] (AzNews.az).

- On 18 March, Azadlıq radio photo and video camera operator Ramin Deko was beaten up at a protest by a group of citizens in front of the embassy of Turkey. Freelancers Tabriz Mirzayev [Təbriz Mirzəyev], Nurlan Gahramanli [Qəhrəmanlı], and Teymur Kerimli [Kərimli] were likewise subjected to physical violence and received injuries of varying severity.

- On 27 August, the police clamped down on a protest by defenders of animals organised by Nijat Ismailov [Nicat İsmayılov] in the capital’s Narimanov [Nərimanov] District. The event was being conducted in connection with the killing of six homeless dogs in an abandoned construction zone. The police exerted physical pressure on the journalists who were covering the event, Nurlan Gahramanli [Qəhrəmanlı], Teymur Kerimli [Kərimli], and Avaz [Əvəz] Hafizli. Policemen were beating and pushing the journalists, and likewise took away their telephones and photo and video equipment, which they only returned after the rally.

- On 9 September, Azel.TV journalist Sevinj Sadigova suffered during coverage of a protest in defence of the political prisoner Tofig Yagublu [Tofiq Yaqublu] outside the Nizami District Court building. In the course of the video shoot policemen shoved Sadigova hard, and she fell, injuring her leg. “Other colleagues suffered too. Some were likewise knocked down, they had cameras and recorders beaten out of their hands”, noted Sadigova.

One attack on the part of unknown perpetrators was recorded. Presumably it was committed by representatives of the authorities or at their behest:

- On 31 August, journalist Rafael Husseinzade [Rafael Hüseynzadə] was beaten up by unknown persons. The journalist reported that he submitted a complaint to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the police without delay; nothing was undertaken, however. In the journalist’s opinion, he had been beaten up for talking about the violence to which he had been subjected earlier by the police.

Likewise, one instance of a non-fatal attack was recorded in the territory of Belgium:

- On 24 July, REAL TV journalist Khatira Sardargizi [Xatirə Sərdarqızı], who was preparing a report about a clash between Azerbaijanis and Armenians in Belgium’s capital, Brussels, was beaten up and received minor injuries.

Likewise recorded was one incident connected with torture in prison:

- On 6 August, the arrested founder and editor-in-chief of the Xeberman.com and Press-az websites, Polad Aslanov, began a hunger strike in protest against arrest on a fictitious charge. In the words of the journalist’s wife, they are exerting pressure on him in the prison. “Because of the start of the hunger strike Aslanov was taken out of a cell for three people and placed in a toilet; they are exerting pressure on him so he would cease the hunger strike”, declared his wife.

National legislation protects journalists from physical attacks. Criminal liability is prescribed for physically assaulting journalists. However, the criminal code article about impeding the lawful professional activity of a journalist was not applied a single time in the course of the year.

6/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

33 incidents connected with non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats were recorded in 2020. In the main it was independent and opposition media outlets that were subjected to such attacks. The main methods in the given category are bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber- (10) and cyber-, DDoS, and hacker attack on a media outlet (10).

In the course of the year the Bastainfo.com website, which has close ties to opposition political parties, as well as Bastainfo.com‘s resources in other domains, were subjected to cyber-attacks a minimum of 4 times:

- On 31 January, the basta2.com news portal was attacked. Access to the website was closed for several days.

- On 31 January, Bastainfo.com‘s Facebook page was subjected to a cyber-attack. The owner of the public channel was changed and the quantity of the page’s likes shrank as a result.

- On 22 April, the Basta news portal was once again subjected to a hacker attack. “The attack was yesterday, the site is demolished”, said the website’s editor Mustafa Hajibeyli [Hacıbəyli]. “Through great efforts we had managed to restore the site and the page [after the 31 January attacks ‒ Ed.], but yesterday the site was demolished anew. We consider that this was a contract job on order from the authorities”, noted Hajibeyli.

- The Bastainfo.com website’s Facebook page was broken into once again on September 10.

Besides that, from 15 through 19 May the website of the Turan news agency and contact.az were subjected to a cyber-attack. The content of the websites was changed as a result. Part of the materials was deleted; it did not prove possible to restore them.

On 24 June, other media resources criticising the government – arqument.az and toplum.tv – were likewise subjected to cyber-attacks. On 22 April, an attack was perpetrated on the abzas.net website. Articles on the websites were deleted, and in some cases altered. The arqument.az website’s Facebook page was likewise subjected to assault. 12,000 subscribers to the page and news published before March were deleted.

In two instances journalists’ personal email accounts and social media pages were subjected to attacks:

- On 2 March, the AzNews.az news portal was subjected to a cyber-attack. The assailants tried to hijack the website’s Facebook page. Attacks also took place against the personal Facebook account of the website’s editor Nailya [Nailə] Balayeva. Fragments of correspondence were deleted.

- On 9 July, several activists, journalists, and media organisations in Azerbaijan lost control over their social media accounts; amongst them was freelance journalist Aysel Umudova. Social media accounts on Facebook were broken into and deactivated with the use of identity credentials. The victims received notifications from Facebook about a query by unknown persons using their identity cards for authorisation of their social media accounts. This is spoken about in a statement by the “Civil Society of Azerbaijan Group”.

One of the widespread methods of non-physical pressure was bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber-. In 7 of the 10 instances, the attacks came from representatives of the authorities:

- On 4 May, AzNews.az correspondent Zaur Gambarov [Qəmbərov] declared that he had been beaten up by two people, including an employee of the State Social Protection Fund (SSPF). In Gambarov’s own words, the incident took place when he set off on an assignment from the editorial office to a branch of the SSPF to research a complaint that the website had received from a local resident. When the journalist began to record the talk on a telephone, an SSPF driver entered the office and began to threaten him. Later the head of the branch came out to see what all the commotion was and tore the telephone from the journalist’s hands. In the words of the journalist, the violence was accompanied by threats to arrest him for critical articles about the administration of the district.

- On 8 May, journalist Khadija Ismayilova reported on her Facebook page that a person in civilian clothing had knocked on the door of her sister’s flat, where the journalist was located during the time of the quarantine. The person said that he was from the police, did not introduce himself, and asked for access to recordings from surveillance cameras – supposedly to investigate a robbery. Ismayilova refused to let him in and asked him to come with a court decree. The visitor summoned the neighbourhood police officer. They continued knocking on the door, intimidating the journalist, and threatening her with a fine.

- On 21 May, journalist Elchin Hasanzade turned to law-enforcement organisations and the media with a complaint of harassment. “It’s been two days already that the chief of Housing Operations Commission number 4 of the city of Mingachevir is coming to the owner of my rented flat and demanding that he evict me – a ‘radical oppositionist’. The bureaucrat is threatening the owner of the flat with problems because by ‘harbouring a radical oppositionist’ he is taking a stand ‘against statehood’. Pressure is being exerted in a similar manner on my wife’s parents. And the chief of Housing Operations Commission number 5 is exerting pressure on owners of a tea house that I frequent so that he would not let me come there anymore”, notes Hasanzade. In Hasanzade’s opinion, the pressure on him is coming from the leadership of Mingachevir’s executive power.

- On 16 August, independent journalist Gular Mehdizade [Gülər Mehdizadə] was summoned to the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The journalist was criticising quarantine measures and the activity of the police. They telephoned her from the ministry and asked her to come in. Mehdizade refused to appear at the MIA without an official summons.

The following incidents belong to attacks that came from unknown perpetrators or non-representatives of the authorities:

- On 23 May, death threats were received by Reaksiya TV head Zaur Gariboglu [Zaur Qəriboğlu] on social media for his materials.

- On 28 July, a campaign began on social networks against Yukselish.info journalist Elchin Hasanzade. On Facebook they started demanding the journalist’s expulsion from Mingachevir. Commenting on this campaign Hasanzade said he believed that the city’s leadership is standing behind this campaign. The journalist said that in such a manner they are trying to force him to shut up.

- On 8 December journalist Arzu Geybulla [Arzu Qeybulla] was subjected to organised bullying on the internet after publication of an article about her on the AzLogos portal. It is asserted in the article that the journalist had displayed disrespect for Azerbaijani heroes and victims of the war with Armenia.

7/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

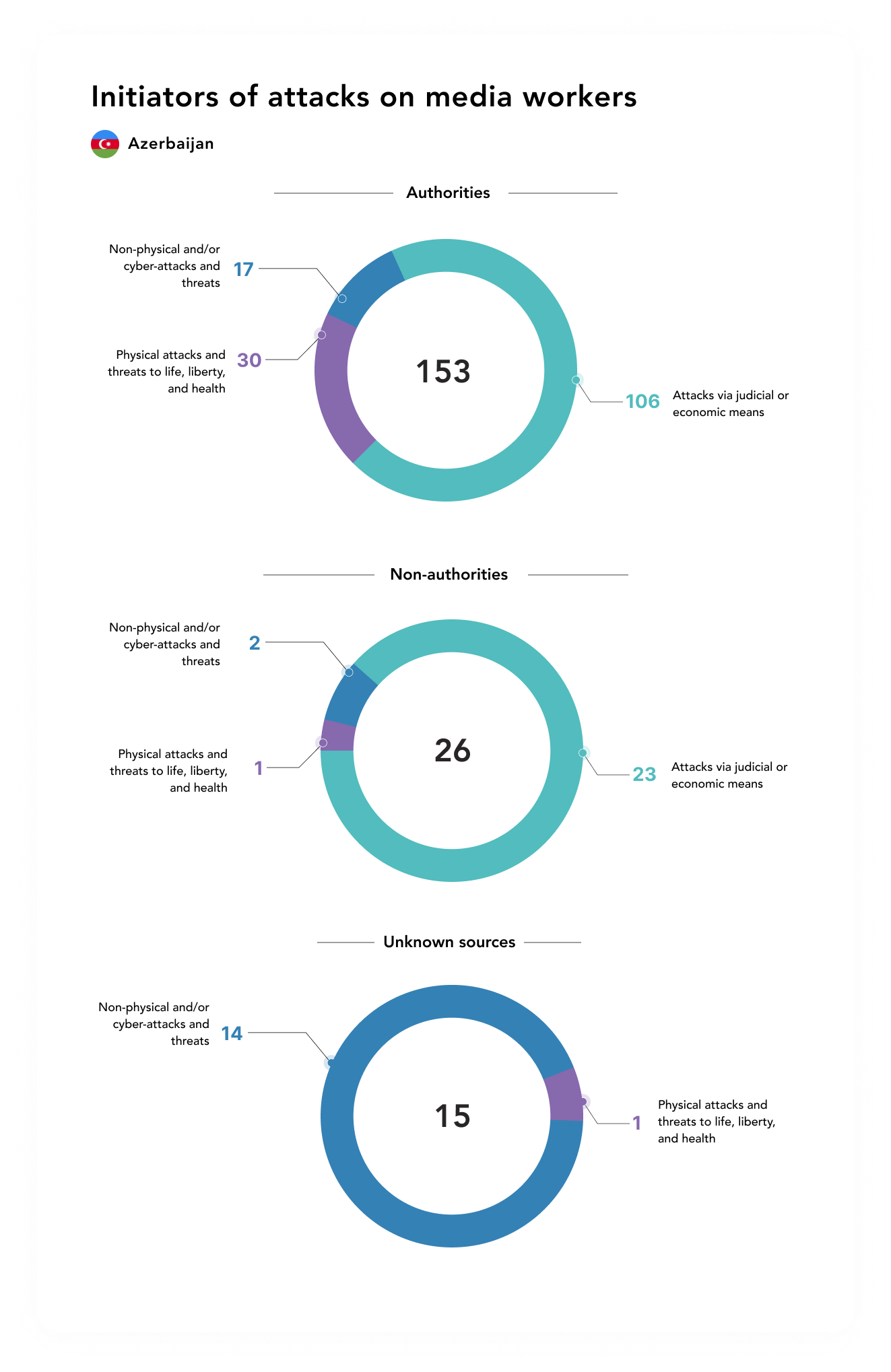

There were 129 attacks via judicial and/or economic means recorded in 2020. In 106 of the instances the attacks were coming from representatives of the authorities. The main methods of pressure were court trials (27), short-term detention (27), and administrative arrests, remand, pre-trial detention or prison (13). Journalists were brought to trial for libel and insults, as well as on other charges. The most noticeable incidents were detentions of journalists whilst executing professional duties, interrogations in law-enforcement agencies, and administrative punishment without the proper legal grounds.

The legislation of Azerbaijan prescribes criminal liability for libel and insults. Journalists were sued no fewer than 12 times under these articles throughout the year. Appearing as plaintiffs in many court cases of this category were government officials or businessmen connected with the government.

- On 10 June, chief of the production amalgamation of the city of Mingachevir’s housing and utilities sector Shahriyar [Şəhriyar] Mustafayev filed suit against journalist, employee of the yüksəlish.info website Elchin Hasanzade, working in the city, and blogger Ibrahim Turksoy. A local court sentenced both journalists to correctional work for a term of one year. On 6 November the court likewise gave Turksoy a suspended sentence of a year of deprivation of liberty.

- On 15 June, the well-known lawyer Aslan Ismayilov [İsmayılov] filed a civil suit against AzNews.az editor-in-chief Taleh Shahsuvarli [Şahsuvarlı] and a suit in special charge procedure. He is demanding the journalist’s arrest.

- On 16 June, the entrepreneuress Malahat Gurbanova [Məlahət Qurbanova] filed suit in special charge procedure against head of the Сriminal.az website Anar Mammadov [Məmmədov]. Gurbanova, engaged in pawning activity, had been offended by the expression “Lombard Malahat”. The court sentenced the journalist to correctional work for a term of one year with the withholding of 20% of his income to the benefit of the state.

- On 26 June, the Supreme Court of Azerbaijan decreed to fine Meydan TV journalist Sevinj Vagifgizi [Sevinc Vəqifqızı] 1000 manats for a publication about falsifications at elections. The suit against the journalist had been filed by a school director [head teacher] who was being accused of rigging the results of the voting.

- On 13 July, the well-known businessman Rasim Mammedov [Məmmədov] filed a civil suit in special charge procedure against Reaksiya internet TV editor-in-chief Zaur Gariboglu for his publications. The plaintiff is demanding that the journalist be arrested and fined 4 million manats.

- On 4 August, the head of the executive power of Neftchala District, Mirhasan Seyidov [Mirhəsən Seyidov], filed a civil suit against the editor-in-chief of the low-budget website bizimxeber.az Adil Huseynli [Ədil Hüseynli] because of his articles. The government official was demanding that the journalist be fined 20 000 manats; the court fined the journalist 3000 manats.

- On 22 August, the head of municipality of one of the villages of Neftchala District filed a suit against the well-known blogger Vafa Naghi [Naqi].The head of municipality is demanding Naghi’s arrest for her publications.

- On 24 September, millionaire Gulaga Gambarov (Tanha) [Gülağa Qəmbərov (Tənha)] filed suit against the legion.az, realmedia.az, dia.az, and heqiqixeber.com news websites. The plaintiff, displeased with the publications in these media outlets, had demanded that each of the websites be fined 100 thousand manats. As of the given moment, the court has fined only the realmedia.az website 100 manats. The court trials in relation to the other media outlets continue.

In 2020 several journalists and bloggers were convicted on various charges. Their lawyers declared that the charges were fabricated and that the journalists had been arrested because of their materials.

- On 19, June Azadlıq newspaper journalist Tarzakhan Miralamli [Təzəxan Mirələmli] was found guilty of hooliganism. The court sentenced him to a year of restriction of liberty. The court required Miralamli to wear an electronic tag and not leave his place of residence from 11 o’clock at night until 7 in the morning.

- On 28 July, blogger Aslan Gurbanov, suffering from a severe form of epilepsy, was arrested for four months on a charge of open calls against the state and inciting nationality, religious, and social discord. The trial is still ongoing.

- On 27 August, blogger Jalil [Cəlil] Zabidov was delivered to the police after critical publications. After some time had passed he was charged with hooliganism. A local court found him guilty and sentenced him to 5 months of deprivation of liberty.

- On 16 October, editor-in-chief of the Yüksəlişnaminə newspaper and head of the “Legal Education for the Youth of Sumqayıt [also known as “Sumgait”]” organisation Elchin Mammadli [Elçin Məmmədli] was found guilty under the “theft” and “illegally storing a weapon” articles of the criminal code. He was sentenced to 4 years of deprivation of liberty.

- On 16 November, journalist and head of the xeberman.com website Polad Aslanov, arrested in 2019, was found guilty of high treason. The court sentenced him to 16 years of deprivation of liberty. On 24 February 2020, Aslanov had a new charge brought against him under article 134 of the CC (threatening murder or the causing of grave harm to health).

- On 8 September, a criminal case was initiated in relation to a group of Azerbaijani bloggers working abroad. In particular, Ordukhan Temirkhan [Orduxan Təmirxan], Gurban Mammadov [Qurban Məmmədov], Orkhan Aghayev [Orxan Ağayev], Rafael [Rəfael] Piriyev, Ali Hasanaliyev [Əli Həsənəliyev], and Tural Sadigli [Sadıqlı] were declared internationally-wanted fugitives, charged with making anti-state appeals.

The websites of several independent media outlets – Radio Azadlıq, the Azadlıq newspaper, the Azərbaycansaatıprogramme, Meydan TV, and the Turan internet television channel have been blocked by court decision since 2017. Along with this, on 19 March 2020, the Plenum of the Supreme Court of Azerbaijan repealed all court decisions in connection with these media and adopted a decision on reviewing the case. The initiator of the closure of the websites is the Ministry of Communications. The Ministry is demanding that not only the websites of the media enumerated above be blocked but all internet resources, including resources on social networks, that are distributing the content of these media outlets.

TAJIKISTAN

An independent expert opinion about Attacks on media workers in Tajikistan report

The mounting pressure on the mass media on the part of Tajikistan’s authorities is driven by several factors. First of all, this is the population’s intensifying discontent with the socio-economic situation. Fearing they might lose control over the situation, the authorities are applying various methods of intimidation in relation not only to journalists but to human rights advocates and civic activists as well, including those found beyond the confines of Tajikistan. Following the example of other totalitarian countries, the Tajik authorities have created “troll factories”, which systematically engage in bullying independent journalists on the internet. Such “factories” protect the interests not only of the authorities, but those of private companies belonging to the president’s relatives as well.

The law enforcement agencies too engage in intimidation of journalists and their relatives. Several journalists convicted in Tajikistan in recent years serve as an example for those who have remained at liberty and continue to write the truth.

Instead of blocking the websites of independent media outlets, the authorities have begun to apply a new technology in relation to foreign news resources writing about Tajikistan: these websites are not blocked, but their loading speed in the browsers of users in Tajikistan is artificially slowed down. Internet speed in the country is ‒ once again artificially ‒ reduced to a minimum. In such a manner, the authorities are trying to block off the country’s population from any truthful information about Tajikistan.

A huge quantity of “independent” media outlets are registered in Tajikistan, but 90 percent of them were created from the outset for business purposes and disseminate only information of an entertainment and advertising character. Practically all of them are loyal to the ruling regime from the moment of creation; their management will never go for confrontation with the authorities in order not to put their business in jeopardy.

A series of media outlets positioning themselves as independent have begun publishing openly propagandistic materials discrediting independent journalists. In the meantime the managers of these media outlets continue to declare about their independence, and even receive grants from international organisations.

Official Dushanbe practically always leaves without commentary the multitude of reports, presentations, and statements by international organisations and democratic countries about the deteriorating situation in Tajikistan with freedom of speech and human rights as a whole, but in so doing it unfailingly indicates that the country is a partner of the international community in the fight against extremism and terrorism. In Dushanbe they know perfectly well that this is a sufficiently strong argument that will make European politicians shut their eyes to everything else. Tajikistan’s authorities cite impressive statistics about verdicts in extremism cases, thanks to which they continue to receive western loans and other aid, including for modernisation of the law-enforcement agencies. However, not many realise that 90 percent of those convicted for extremism in Tajikistan are absolutely innocent people.

Khayrullo Mirsaidov

Independent journalist

1/ KEY FINDINGS

69 instances of attacks/threats in relation to professional and citizen media workers and editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Tajikistan in 2020 were identified and analysed in the course of the research. The data for the research were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Tajik, and English languages using the method of content analysis. Facts that have previously not been made public and were obtained using the expert interview method were likewise used in the report. A list of the main sources is presented in the Annex 3.

- The number of attacks on media workers on the part of the authorities increased significantly in Tajikistan in 2020. This was connected first and foremost with the elections to Tajikistan’s parliament and the presidential elections that took place in 2000.

- The overall quantity of attacks on journalists and media workers in Tajikistan in all three categories increased by a third in comparison with the previous year. 49 attacks were recorded in 2019, while in 2020 the number was 69.

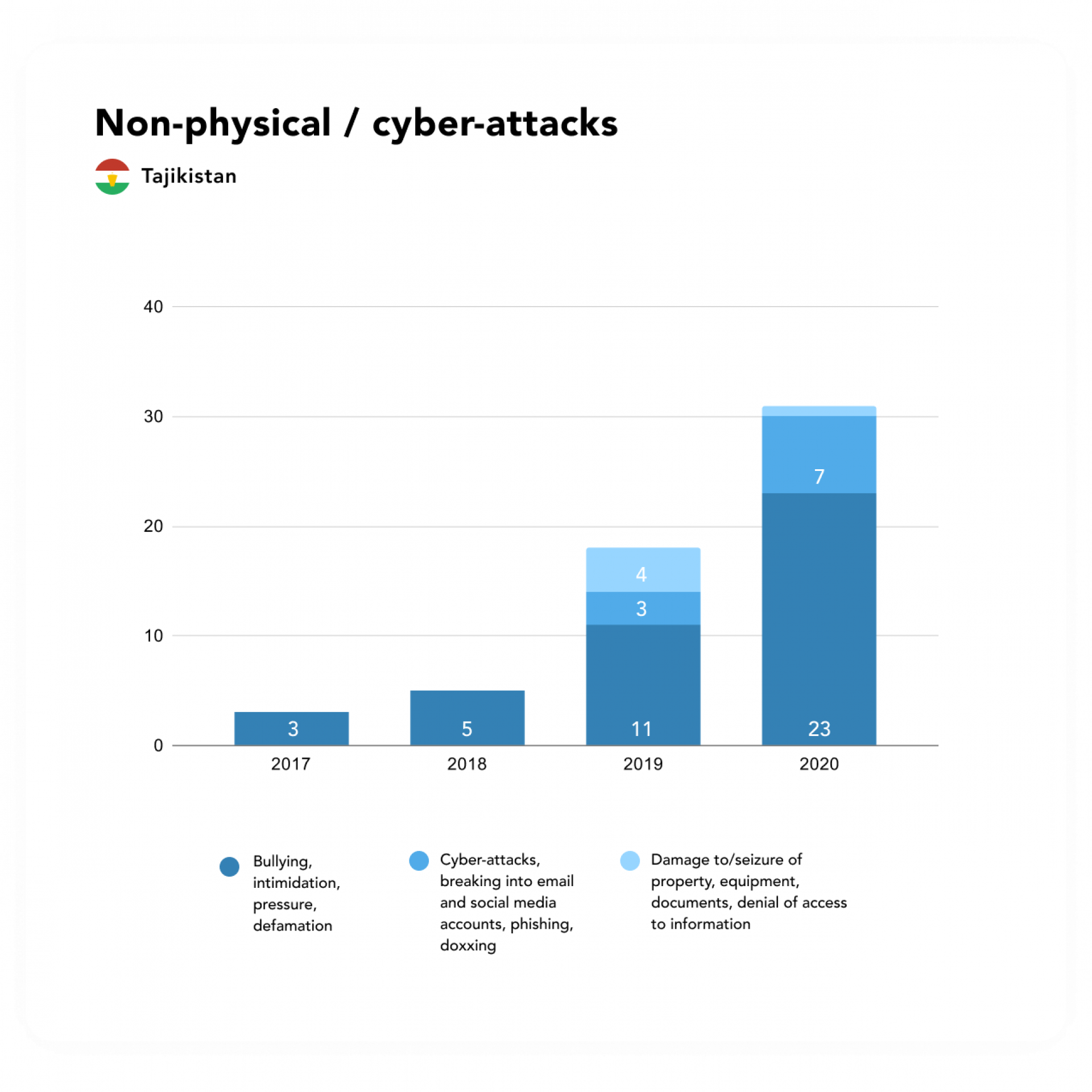

- In 2020, the quantity of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats increased from 18 incidents in 2019 to 31 in 2020.

- The main target of attacks on the part of Tajikistan’s authorities this year was journalists collaborating with publications accused of being involved with terrorist and extremist groups that are banned in the republic. The main method of pressure on the part of the authorities was publication of journalists’ stolen personal information.

- Attacks on journalists within the framework of quarantine restrictions began even before mass media editorial offices were prohibited from furnishing alternative information about the spread of COVID-19 in Tajikistan. After a law on penalty sanctions in relation to media outlets entered into force, Tajik journalists began publishing only official data about the pandemic.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN TAJIKISTAN

In 2020, as in 2019, Tajikistan took 161st place out of 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders annual freedom of the press rating, ending up between Burundi and Iraq.

There were two important political events in Tajikistan in 2020: elections to the republic’s parliament took place in March, and presidential elections in November.

According to the data of Tajikistan’s Central Electoral Commission, the majority of the votes in the parliamentary elections were garnered by the presidential party – the People’s Democratic Party. At the elections of the president, the current head of the republic, Emomali Rahmon, who has been in power since 1992, won for the fifth time.

The parliamentary elections in Tajikistan went by practically unnoticed; the attention of society and the press was riveted to the situation with the coronavirus. Despite the large quantity of sick people with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19, Tajikistan’s authorities wholly refused to acknowledge the existence of infected persons in the republic.

The media’s attempts to provide at least some kind of coverage of the topic of the pandemic were harshly thwarted by a “troll factory”, which was working actively on social networks.

The existence of the coronavirus in Tajikistan was announced on 30 April, 24 hours before a large World Health Organisation delegation arrived in the country. After this, journalists began to more actively cover the topic of the pandemic, including putting together lists of those who had died from the coronavirus. According to the data that independent publications managed to confirm, more than 400 people perished in Tajikistan in the period between April and December 2020 from COVID-19 and its effects. Officially, the death of 90 people has been acknowledged. Among the victims of the pandemic – a minimum of five Tajik journalists.

In July 2020, administrative liability was introduced in Tajikistan for spreading information about the coronavirus pandemic in the republic. If a media outlet publishes information that differs from the Ministry of Health’s data, it faces a fine of up to 1000 US dollars; an individual can be fined 50 US dollars for such an act.

Taking into account that Tajikistan’s independent publications are experiencing financial difficulties, they all stopped seeking alternative data about the situation with the coronavirus in the country.

On the eve of the presidential elections, in the summer of 2020, the authorities intensified harassment of Tajik dissident journalists. Shown on all the state television channels was the three-part documentary film Hiyonat(Betrayal). The film is devoted to the activity of the banned Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT). The party is being accused of inciting civil war in Tajikistan in the 1990s and of an attempt to overthrow the state in 2015.

One of the episodes of the film is devoted to the activity of dissident journalists, in particular the Akhbor.com internet portal, founded by Mirzo Salimpur, a Tajik journalist living in Prague. The authors of the film cite the private personal data of Tajik journalists who had worked with this internet publication: places of residence and bank transfer data.

After the film had been shown, the publication was recognised in Tajikistan as banned, and Salimpur was forced to shut it down. In his announcement, he clarified that after the Supreme Court’s decision on including Akhbor in the list of banned internet sites in Tajikistan, “many legal problems arose in the site’s activity”. “Unfortunately, because of this baseless decision, journalists cannot freely send their materials, while experts and government officials cannot speak with us on topics of current interest. They all could be charged with cooperating with a banned publication”, declared the Akhbor editor-in-chief.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

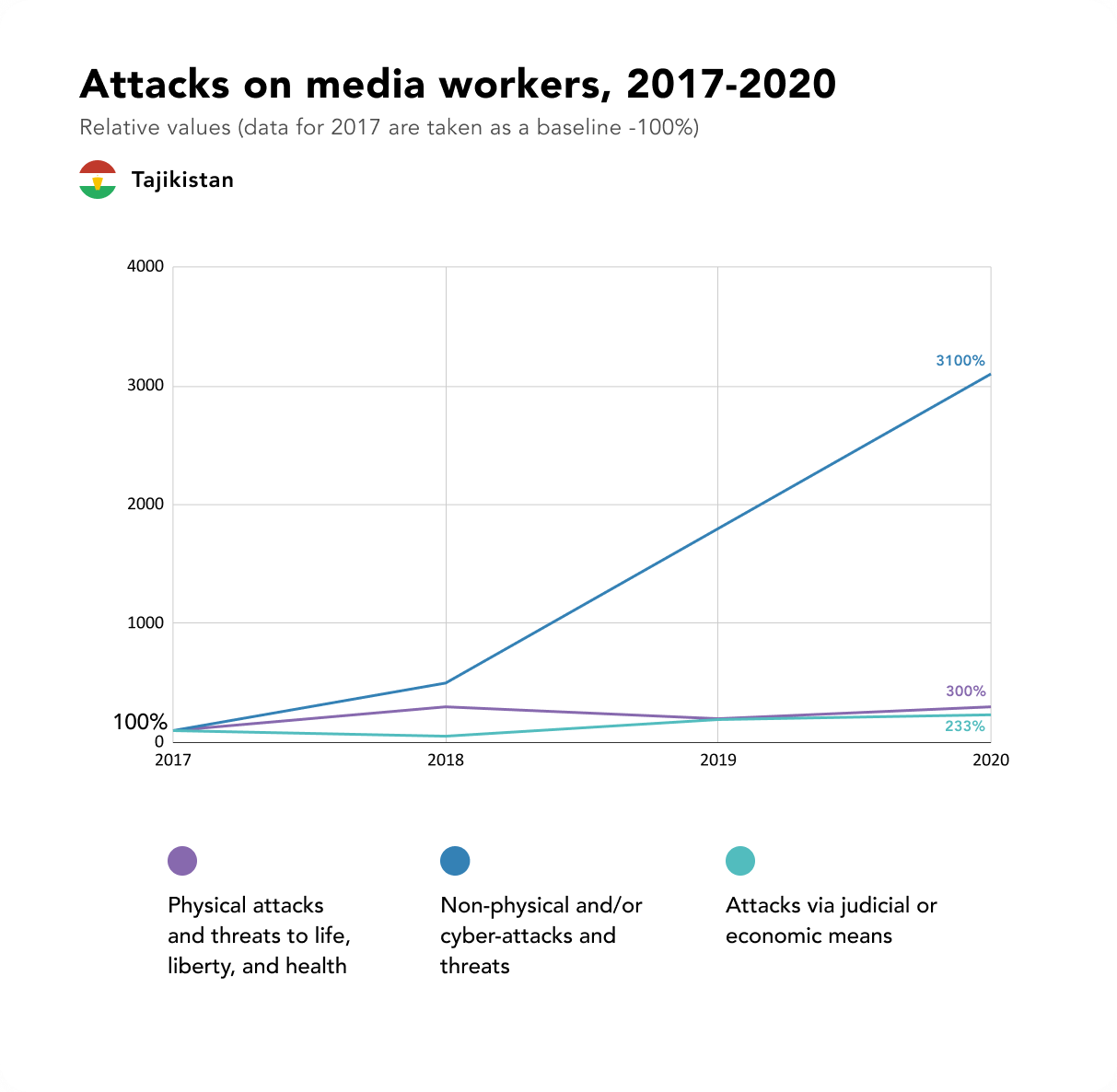

The graph below represents an overall analysis of the three main categories of attacks/threats in relation to journalists of the territory of Tajikistan and on Tajik journalists who had abandoned the country but were continuing professional activity beyond the border in 2020. The number of attacks on media outlets and journalists has increased by 25% in Tajikistan over the past year in comparison with 2019.

In 2017-2019, 64 out of 81 incidents consisted of attacks by the authorities, while in 2020 representatives of the authorities became the initiators of 51 out of 69 attacks. The quantity of attacks in all three categories increased in 2020. The number of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats went up noticeably – from 18 instances to 31.

And this is only those instances that could be recorded from open sources or in personal conversations with journalists. As before, it is not customary in Tajikistan to record cyber-attacks and threats. Journalists prefer not to file reports of crime about attacks, as it is complicated to prove them; besides that, they have grown accustomed to threats and do not attach great significance to them.

In 2020, a repressive measure was selectively applied in relation to an entire editorial office during the time of the presidential elections. None of the journalists and camera operators of the Asia-Plus media group received accreditation to cover the electoral process after applying.

4/ PRESSURE ON JOURNALISTS UNDER THE PRETEXT OF RESTRICTIONS CONNECTED WITH THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

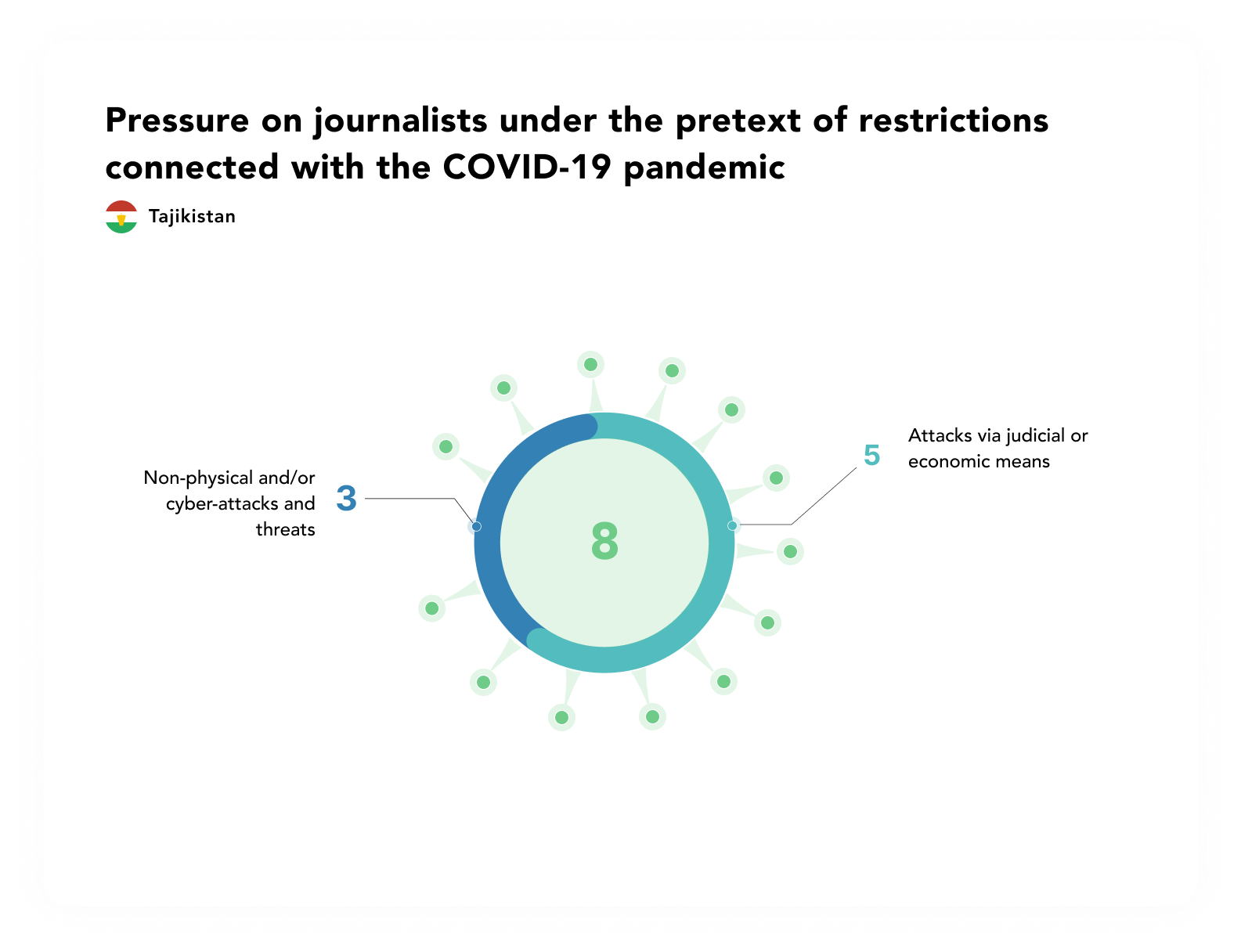

Eight attacks on journalists associated with quarantine restrictions were recorded in Tajikistan: five attacks via judicial and/or economic means and three attacks that were in the nature of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats. Above all, they are associated with journalists’ attempts to bring the attention of the authorities and the population to cases of death from pneumonia in Tajikistan.

Until 30 April, Tajik authorities officially did not recognise the existence of coronavirus in the country, even though journalists had begun reporting on deaths of patients with symptoms resembling those of COVID-19. The authorities officially refuted the information of the independent publications, while journalists who dared write about people getting infected with the coronavirus were subjected to harassment on social media.

- On 5 March, two journalists from the independent publication CCCP, Sitora Safarova and Sherali Davlatov, were subjected to a lengthy interrogation. They were detained as they were trying to photograph people buying products. The population in the republic had begun mass stockpiling of food at that time. The journalists were accused of sowing panic among the population. After the publisher intervened, the journalists were released.

- On 30 March, unknown persons, most likely using fake accounts, spread libellous material on Facebook against a journalist for her commentary about how the real situation with COVID-19 may be being covered up in Tajikistan. The unknown perpetrators posted a letter from a “doctor”, who was insulting the journalist, calling her a fallen woman.

- On 1 April, journalists from Radio Ozodi (the Tajik service of Radio Liberty), who were among the first to report on cases of death from the coronavirus, did not get extensions of their accreditation in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- On 26 April, an anonymous call was made to the Asia-Plus editorial office, with threats of reprisals and insults addressed at the journalist Avazmad Gurbatov (Abdullo Gurbati). Besides that, a video was posted on YouTube in which unknown persons called Abdullo a traitor because he was covering events connected with the COVID-19 epidemic in Tajikistan. In their words, he was deliberately stirring up the situation in the country, carrying out an order from dissidents.

5/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

Three instances were recorded in 2020, two of which were non-fatal attacks while one falls under the category of “abduction, illegal deprivation of liberty”.

- Twice – on 11 and 29 May – the young Tajik journalist Avazmad Gurbatov (Abdullo Gurbati) was subjected to beatings. In the first incident, the culprits were not found, despite the fact that Gurbatov had promptly informed law-enforcement agencies about the incident. The journalist was beaten in the immediate vicinity of his home after work at that time.

- The second incident took place in Khuroson District, where Gurbatov had travelled on assignment from the editorial office in order to write a story about how this population centre was recovering after a mudslide. The journalistic community managed to get law enforcement structures to intervene. The culprits were found and were fined by court decision.

- On 17 March, the journalist Nisso Rasulova, who is actively fighting violence against women, was abducted near her home. The journalist was returned home after several hours. What was taking place with her at this time is unknown, but after the abduction Rasulova stopped conducting active civic work.

6/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

In comparison with 2019, in 2020 the quantity of recorded attacks increased by 13. As we have already noted, in Tajikistan journalists are in no hurry to report about such attacks; for this reason their real quantity is likely much higher.

The main method of non-physical pressure on journalists in 2020 became defamation and spreading libel about media workers or media outlets, as well as identity theft/ phishing/doxxing. In 2020, there were more attacks on the part of representatives of the authorities (20) than from unknown perpetrators or non-representatives of the authorities (11).

The state used everything at their disposal to defame journalists, especially dissidents who had been forced to leave Tajikistan under pressure from the authorities: state television channels and internet publications, and a “troll factory” that functions with the support of state bodies, as well as independent publications collaborating with the security agencies.

- In particular, the CCCP newspaper accused seven Tajik journalists working beyond the country’s borders, including the editors of the Radio Liberty Tajik service based in Prague, of links with the banned Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan. This party had been the only opposition force to pose any real competition to the presidential party. In 2015, the leadership of the IRPT was charged with attempting to overthrow the state and the party was recognised as a terrorist organisation.

- Libellous and offensive material about the independent journalist Rajabi Mirzo was published in the state newspaper Jumhuriyat. The author was named as a graduate of the Centre for Journalistic Investigations. Immediately after the publishing of this article, the director of the Centre, Khurshed Atovullo, declared that he had never had any graduates with such a name.

7/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

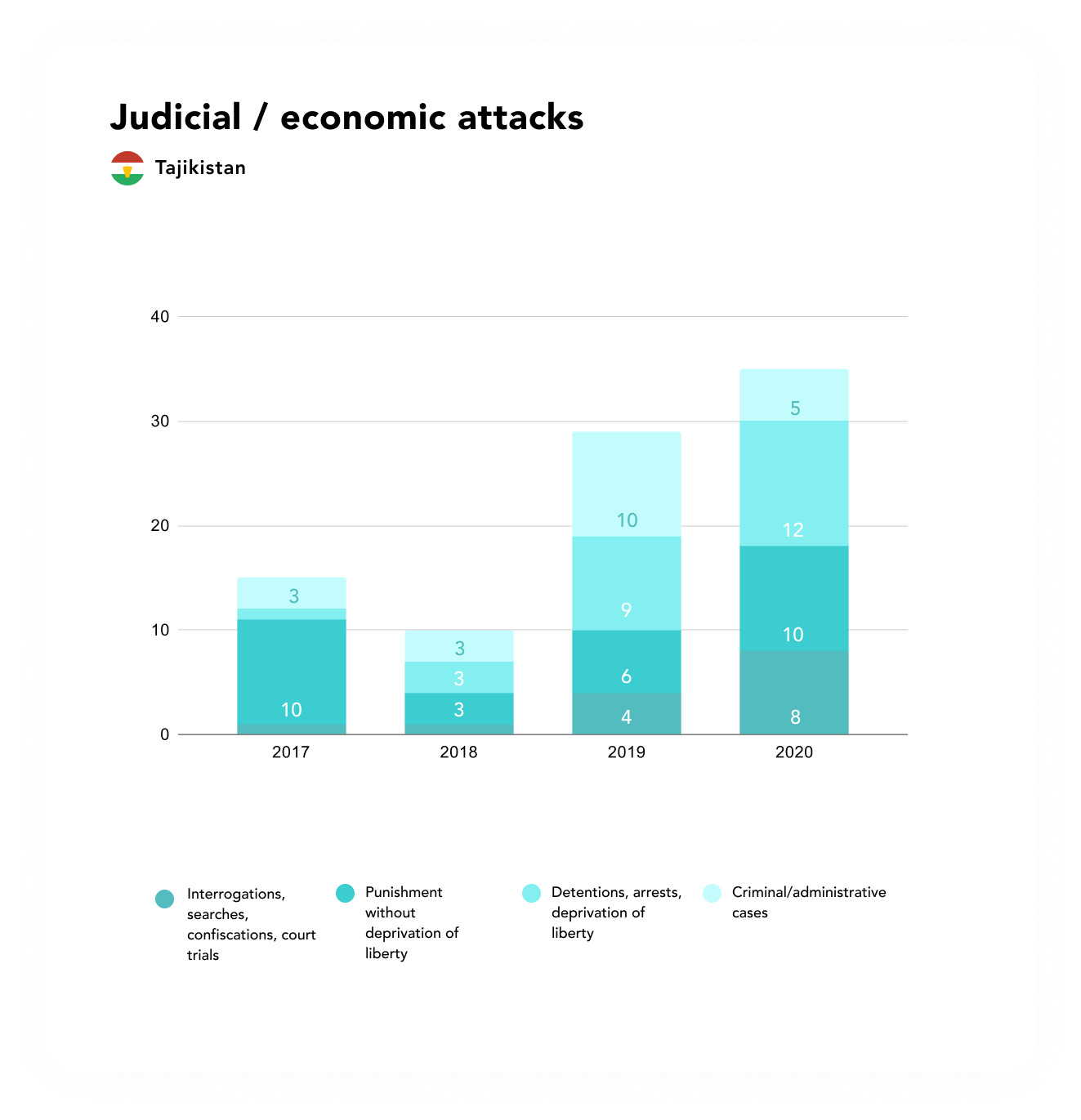

The three main methods of pressure on media workers in 2020: ban on entering the country, denial or revocation of a visa/accreditation; shutting down a media outlet/blocking an internet site/request to remove or block articles/seizure of an entire print run; and court trial.

In 2018, an amendment was introduced to the law on elections of the president, according to which Tajik publications require accreditation, just like foreign media outlets, in order to cover the voting. Registration at the Ministry of Culture is necessary for this.

- On 28 September, the Central Commission for Elections and Referendums of the Republic of Tajikistan denied accreditation for the upcoming presidential elections to nine Asia-Plus journalists. This was the result of time wasting with respect to registration at the Ministry of Culture, which in its turn explained that it had not received permission from the State Committee for National Security.

- Another such incident, likewise associated with the elections of the president, took place with a journalist from the Nastoyashcheye Vremya [Current Time] television channel, Anurshervon Aripov. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Tajikistan did not like how he had covered the president’s pre-election meetings with the populace. As a result, the journalist had his accreditation revoked.

Shutting down a media outlet/blocking an internet site/request to remove or block article/seizure of an entire print run is the second of the most important methods of pressure.

- On 10 March, the internet sites of Tajikistan’s large independent publications (Radio Ozodi, Avesta, Faraj, Asia-Plus) were blocked. All of the news websites were unblocked on the eve of the presidential elections that took place in Tajikistan in November, but they were blocked once again after the results of the voting had already been announced.

- On 9 April, the Supreme Court of Tajikistan adopted a decision on the blocking of the Nahzat.ru internet portal, a mirror of which is accessible through the internet address Nahzat.org. This is the portal of the banned Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan. The court granted the request of the general prosecutor, in which it was said that Nahzat.ru is associated with terrorist and extremist organisations banned in Tajikistan.

- On 13 November, the Akhbor portal announced its shutdown due to pressure from the authorities on journalists working with the publication.

Several court trials were initiated in relation to journalists and media outlets in 2020:

- On the basis of a decision of the Supreme Court of Tajikistan on 15 February 2020, also adopted on the basis of a request from the General Prosecutor’s Office, Akhbor was included in the list of internet sites banned on the territory of Tajikistan. The authorities accused the website of servicing terrorist and extremist organisations banned in Tajikistan – the Islamic Renaissance Party, the National Alliance of Tajikistan, and others. Then began harassment and persecutions of journalists working together with this internet publication. On 13 November, the internet site’s editor was forced to shut the publication down completely.

- On 16 April, a court sentenced the independent journalist Daler Sharifov to a year of deprivation of liberty. The court found him guilty of inciting religious hate. The state prosecutor was demanding that the journalist be sentenced to 2 years 4 months of imprisonment. Sharifov was released from prison on January 29 2021.

- A third court trial has been unprecedented for Tajikistan. On 1 October, the publication Vecherka became the co-defendant in a lawsuit brought by the businessman Tohir Ibrohimov against the fashion designer Parvin Jahongiri, who had accused her former employer of battery. After Vecherka published a story on the subject, Ibrohimov filed suit against Jahongiri. Her lawyer considered that the only defendant in the given lawsuit can be the publication, and filed an objection. After this, the publication was recognised as a co-defendant. The plaintiff is demanding recovery of damages for emotional distress in an amount of 100 thousand somoni for offence to his honour and dignity.

- On 15 October, the General Prosecutor’s Office of Tajikistan initiated a criminal case under the criminal code article on fraud in relation to the editor-in-chief of the isloh.net site, Muhammadiqboli Sadriddin. It was suggested that the opposition journalist had misappropriated 430 thousand dollars worth of funds of three citizens of Tajikistan. The journalist called the charge “groundless” and declared that he himself has still not been repaid a debt of many thousands.

TURKMENISTAN

An independent expert opinion about Attacks on media workers in Turkmenistan report

The report offers a very detailed picture of the dismaying context in which independent media continue to operate in Turkmenistan. Beyond censorship, verbal and physical harassment—a practice that is now endemic—has represented the default approach regulating government-media relations for much of the post-Soviet era: this proposition explains the very limited number of independent media operators working in Turkmenistan. The report does an excellent job in capturing both the niche nature of independent journalism in Turkmenistan and the punitive approach whereby the regime continues to repress the activities of these few operators. Interestingly, it also brings forwards a series of worrying new opportunities for repression intrinsic to the politics of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Here, the report sketches out with great precision the repressive efforts complementing the government-imposed media ban on infection rates in Turkmenistan: this was a taboo topic, one that the regime was willing to contain even by policing Instagram posts and scouting the telephone contacts’ list of ordinary citizens.

This report makes an equally important contribution when it describes the violence defining regime efforts to present Turkmenistan under Berdymukhammedov as living through a Golden Age. Here, the report describes the capillary control exerted by the regime on Turkmenistan’s information flows, offering detailed examples of citizens being harassed, verbally and physically, for even the smallest complaint about the disastrous state in which Turkmens live their daily lives. Turkmenistan is not a place where people can speak their mind freely: the report offers a serious of very detailed, and—even for the expert eye—hard-to-find data to describe another year in Turkmenistan’s inhospitable media landscape.

Dr Luca Anceschi

Senior Lecturer in Central Asian Studies,

University of Glasgow

Author of the report – Ruslan Myatiev, Turkmen.news

1/ KEY FINDINGS

2020, the year of COVID-19, was notable in Turkmenistan not only for the introduction of public health restrictions, the closing of the country’s borders, the deepening of the economic and food crisis, and a rise in protest sentiments. For Turkmen citizen and professional journalists, the year brought new prohibitions on freedom of speech, an increase in the number of physical, non-physical, and judicial attacks, persecutions of those who exercised or attempted to exercise their right to freedom of information, and harassment of relatives.

Data about the attacks was obtained from open sources in the Russian, Turkmen, and English languages using the method of content analysis. Material that has previously not been made public and was obtained using the expert interview method was likewise used in the report. A list of the main sources is presented in the Annex 4.

Considering the lack of openness of information in Turkmenistan and the hollowed out information field in this country, the number of non-physical, judicial, and economic attacks and threats (of blackmail, intimidation and humiliation, firing or demotion, and the like) recorded in 2020 corresponds to the 2017-2019 level.

- One physical attack on a journalist and one on a relative of someone who had publicly voiced criticism of G. Berdimuhamedov was recorded in 2020. This quantity more or less corresponds to the average indicator for 2017-2019.

- Six instances have become known in the past year of the authorities conducting judicial attacks on citizen activists who were suspected by the Ministry of State Security (MNB) of Turkmenistan of working with foreign media outlets or on those who had expressed their position on social media with regards to events that had taken place. This indicator is also equal to the average annual numbers for 2017-2019.

- Compared with the data for 2017-2019, more became known in the year under consideration about incidents of non-physical attacks on sources of information. About thirty such incidents were recorded.

- In 2020, attacks or restrictions for media outlets under the guise of COVID-19 pandemic quarantine measures were not recorded in Turkmenistan.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN TURKMENISTAN

Turkmenistan has consistently ranked near the very bottom (177-180) of the Reporters Without Borders NGO’s annual rating since 2015. In the rating for 2020, Turkmenistan took 179th place, ending up between Eritrea and North Korea.

Analysis shows that in comparison with the previous year, the situation with political freedoms and civil liberties in Turkmenistan did not improve in 2020, and even fell for some of the indicators. Over the period under analysis, there began to be more public expression by citizens of their dissent toward the policies of president Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov’s regime. As can be expected, one can see a rise in incidents of the use by authorities of harsh repressive measures towards both those whose work is directly connected with journalism and the dissemination of information, and those who had reported on social media or through foreign media outlets about their personal problems or about arbitrary actions on the part of representatives of the structures of power.

The dynamics of the growth of civic activism in Turkmenistan and its harsh suppression are associated with the deep economic and financial and social crisis that has gripped the country, as well as the introduction of severe restrictions on movement in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic, the existence of which the authorities continue to stubbornly deny. Life has become unbearably difficult for the overwhelming majority of the country’s population. The number of people who have been left without a means of subsistence and have fallen into a desperate situation increased in 2020. People’s desperation consists additionally of the fact that they cannot obtain justice, or have their problems resolved inside the country. They understand the futility of resorting to the courts, the prosecutor’s office, to local media outlets, and even personally to the country’s president. This desperation forces many to overcome their internal fear of the state and to seek help or protection abroad.

Protest sentiments are growing both inside the country and among citizens of Turkmenistan living abroad. Many citizens have begun using protected methods of transmitting information to human rights organisations and foreign media outlets that pose no danger to themselves.

3/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

On 12 August 2020, in Ashgabat, yet another attack was perpetrated on the journalist Soltan Achilova [“Açylowa” in Turkmen] – one of the few people who is openly working with foreign media outlets while still living in the country. S.Achilova is 70 years old. In previous years, she had been subjected to numerous assaults by unknown persons of an athletic build who were trying to forcibly take a camera from her during photo shoots, hurting her in the process.

Achilova is convinced that employees of the Ministry of State Security and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), as well as their henchmen from among people with a criminal past, are behind all the attacks against her. This time, a policeman assaulted S.Achilova during a photo shoot of a school fair. His aim was to impede S.Achilova in carrying out her professional duty and to snatch the camera from her hands. The scuffle between the policeman and the elderly woman was accompanied by loud accusations that the journalist was “going against state policy” and threats to take her to a police station. It all ended with S.Achilova managing to break free and flee the location of the photo shoot without receiving serious bodily injuries in the form of bruises and abrasions, as had been the case in prior years.

On 15 October, a knife wound was received by a relative of a person who had openly voiced criticism of G. Berdimuhamedov’s regime on the internet. A resident of the village of Agalan of Serdarabat [now Çärjew] District of Lebap Region, Babajan Taganov [Taganow] is the brother of Dürsoltan Taganova, who, whilst in Turkey, criticised the dictatorial regime in Turkmenistan in her video statement on the internet. On the eve of the attack, B. Taganov had been forcibly taken to a police station, where he had been beaten up as a result of his sister’s statement and his mother Merýemgül Taganova on the internet and for their participation in a protest movement abroad. The fact that the criminal case that was launched into the stabbing of B. Taganov was subsequently dropped indicates that the stabbing was perpetrated by people having a direct relation to the Ministry of State Security or the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

4/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL OR ECONOMIC MEANS

On 15 September in Turkmenistan, Ashgabat resident Nurgeldi Halykov [Halykow] was sentenced to four years of deprivation of liberty. Formally he was convicted for fraud, but in reality it was because he had forwarded a photograph of members of a WHO mission who had visited Turkmenistan in June to the editorial office of the turkmen.news publication. Nurgeldi had taken this photo from the Instagram page of an acquaintance of his. The special services first tracked down this young woman, and then found N. Halykov through the contacts in her telephone. Turkmenistan’s criminal code does not have a punishment for forwarding a photograph that does not contain a state secret abroad. However, the fabrication of criminal cases in relation to undesirable people is widely practiced in the country. And that is just what happened with N. Halykov. Employees of the Ministry of State Security fabricated a case of fraud against him (ostensibly he had borrowed a large sum of money from his friend and not returned it) and locked the young person away for 4 years.

“Nurgeldi Halykov’s conviction exemplifies the absurdity of the trumped-up charges used by the authorities to gag the free press’s few remaining representatives. He risks being tortured in prison”, underscores the international organisation Reporters without Borders in its announcement, and calls upon Turkmenistan’s authorities to free Nurgeldi at once, and likewise asks OSCE representative on freedom of the media Teresa Ribeiro to strongly condemn the young person’s arbitrary detention.

Yet another instance of an analogous combination attack is associated with resident of the city of Mary, Irina Misnik, and her common-law spouse Muhamed Shamsetdinov [Şamsetdinow], whom the local special services, in connection with the appearance on the internet of still photos and articles from the Mary region, had begun to suspect of working with media outlets abroad. Irina Misnik’s detention took place on 10 December, International Human Rights Day. Irina could not move about on her own, because not long before this she had had a bad fall that had resulted in a compound fracture in her leg. Despite this, she was held for 48 hours in detention. Her spouse Muhamed was arrested for 15 days by the sentence of a court. Employees of the Ministry of State Security presented the case as though Muhamed had caused harm to Irina’s health out of motives of hooliganism. It is assumed that the spouses had been tortured or had been intimidated to such a great extent that after the expiration of the term of arrest, I. Misnik and M. Shamsetdinov are afraid to talk even with their loved ones about what had been done to them during the interrogation. Both were fired from work after this whole story (both had been working at private firms). It can be said with confidence that workers of the Ministry of State Security are behind the firing.

Yet another instance of a judicial attack was perpetrated on 5 September 2020 in relation to 48-year-old «Nebitdagneft» directorate lawyer Pygamberdy Allaberdyev [Allaberdyýew]. Even though this incident is not connected with journalistic activity directly, it does have a relation to freedom of speech and to freedom of expression of opinion. P. Allaberdyev had expressed his position in relation to calls for protest voiced in opposition chat rooms by way of a comment or a like. For this, a criminal case was fabricated against him under the “hooliganism” article of the criminal code and he was sentenced to six years of deprivation of liberty.

P. Allaberdyev’s case, just like all analogous incidents, simply does not hold water. This is the crude, ham-fisted work of Ministry of State Security employees, who arranged for a stranger to approach him and at first verbally, and then physically, provoke a fight. As expected, the police appeared at the scene of the incident and the unknown person, having pointed at P. Allaberdyev as the instigator of the fight, calmly walked away while P. Allaberdyev was detained. His trial took place behind closed doors, in the building of the pre-trial detention centre; every lawyer in the country refused to represent P. Allaberdyev’s interests, understanding that the Ministry of State Security was behind this case and that doing so might lead to trouble for them.

A similar story also took place in June with Ashgabat resident Murat Dushemov [Duşemow], who had also openly voiced his opinion about the regime online. Human rights advocates reported on his detention; however, nothing about the subsequent fate of M. Dushemov is known with certainty. Radio Azatlyk has reported that the man has been transferred to house arrest.

In August 2020, the Turkmen Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights and the Memorial human rights association reported about the detention of 24-year-old Turkmenabat resident Reimberdi Kurbanov [Gurbanow] for a statement made online, and of yet another resident of Lebap Welaýat (Region), whose name is not given, who was arrested for 10 days for attempting to send photographs abroad.

As in the 2017-2019 period, the special services reduce all incidents of the detention, arrest, and deprivation of liberty of citizens for correspondent activity or for freedom of speech cited above to concrete articles of Turkmenistan’s criminal code. This was the case with G. Matalayev [Matalaýew], S. Nepeskuliyev [Nepeskulyýew], H. Allashev [Allaşow], and others who received a real or suspended term of punishment ostensibly for fraud, possession of prohibited tobacco, naswar [a moist powdered tobacco snuff popular in the region ‒ Trans.], or for narcotics.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

Nearly all of the instances of physical and judicial attacks described above were combined by Turkmenistan’s special services with non-physical attacks. In 2002, the practice of using threats to life and health was significantly expanded and affected many more citizens than in all previous years.

There is an unspoken prohibition on women driving motor vehicles that is in effect in Turkmenistan. In September, a group of approximately 30 women in Ashgabat initially applied in writing to the head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the general prosecutor, and the president with a demand to be issued new drivers’ licenses to replace licenses with an expired term of validity. Not having gotten a reply, they brought the work of the road police office to a standstill. After a week had passed, the women made an appointment to see head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs M. Chakiyev [Çakiýew], but he refused to see them. When the women went to the GAI [State Automobile Inspectorate, the road police ‒ Trans.], an attempt was made to disperse them by force. As a result, one woman was knocked unconscious, while another received bruises and abrasions from the policemen’s actions.

The story went on for nearly two years and received coverage in media outlets abroad, after which each of the women began to be summoned, one at a time, by place of residence, to a police station, where they were warned that “they should not henceforth go to the GAI, that they are now being spoken to nicely, but if they don’t listen, then problems will be created for them and their relatives.”

If a citizen of Turkmenistan makes contact with publications abroad or posts his or her appeal on the internet, then he or she will certainly be subjected to repressions on the part of employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Ministry of State Security. If a citizen of Turkmenistan is not living in the country, then the state’s machine of repression will start to targe the relatives of those who dare to make a statement online.

Thus, the parents and relatives of 36-year-old Azat Isakov [Isakow], who has been living in Russia for ten years, were subjected to humiliations and threats. The Ministries of Internal Affairs and State Security are thereby striving to get the parents to influence A. Isakov and demand that he not to make statements criticising the regime online.

Serving as a classic example is the story of 26-year-old Ashgabatian Rozygeldi Choliyev [Çoliýew] ‒ a former student at a higher educational establishment in Karachay-Cherkessia [in Russia ‒ Trans.]. R. Choliyev, using the online handle “Oraz”, had posted several video appeals with a critique of G. Berdimuhamedov’s regime on the internet. Through its colleagues from the FSB and Turkmenistan’s consulate in Moscow, Turkmenistan’s Ministry of State Security attained R. Choliyev’s expulsion from the higher educational establishment. Pressure began on Rozygeldi’s relatives inside the country.

His father, Annamyrat Choliyev, age 59, a nurse at a military hospital in the settlement of Bikrova (just outside Ashgabat), was taken to the building of the Ministry of State Security in the vicinity of Ashgabat’s Russian bazaar, where they demanded from him to summon the son home; otherwise, they threatened him with dismissal from work and confiscation of their three-room flat. After the Ministry of State Security, R. Choliyev’s father and his mother, the pensioner Ogulmaral Choliyeva, were taken on numerous occasions to the police station, where they were interrogated for several days in an effort to get them to ensure that their son would no longer make statements on the internet.

A brother, Merdan, a specialist in installing video cameras, was demoted and warned of dismissal in the event of the appearance of new video statements from Rozygeldi on the internet. A sister, Gulshat Choliyeva [Gülşat Çoliýewa], who had worked 10 years at the state company «Altyn Asyr» (the mobile communications operator), was demoted at the end of September and transferred from the company headquarters to work at one of the outlets selling SIM cards. Before this, a high-ranking official at the company gave orders to conduct an audit of her work for the past 4-5 years.

The Turkmen authorities do not tolerate those who, in their opinion, air their dirty laundry in public. Even a statement on the internet or in media outlets abroad about one’s purely personal everyday problems comes back to cause problems and trouble for the one who made the statement.

On 16 December, Anna Kumykova, a mother of two children who had been left homeless with the two children and belongings, published a video appeal to president G. Berdimuhamedov in the turkmen.news publication, with a request to render her assistance in restoring justice and the allotment of housing. Communication with the woman has been lost since 17 December. Nothing is known to this day about her fate and about the fate of her children.

Gülsenem Taganova, working as a gardener for the closed joint-stock company «Hyzmat» of the «Turkmenneftegaz» amalgamation, was waiting in a queue for 13 years for the flat she is entitled to. Housing is furnished to employees with a 50% discount. In this time, both those who had been ahead of her in the queue and many who had come after her had received flats. The woman had filed statements and complaints with all the state bodies of Turkmenistan, but to no avail. Then she spoke about this to the Khronika Turkmenistana publication. After this, Gülsenem was fired, while an unknown person, on instructions from the Ministry of State Security, left the woman without communication, having cut through the home’s telephone wire in a one-room flat.

ANNEX 2: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (AZERBAIJAN)

- Turan — an independent news agency. The agency distributes news, analytical articles, and overviews from Azerbaijan.

- Meydan.TV — a weekly online television channel. Its mission — to inform active members of society about the state of affairs in politics, the economy, and social life; to offer a platform for open and diverse discussions on all topical questions concerning Azerbaijani society.

- Voice of America — a multimedia news organisation in the USA that produces content in over 45 of the world’s languages for audiences with limited access to a free press.

- Toplum.TV — an Azerbaijani news site.

- Xural — an Azerbaijani news site.

- Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Center (EMDS) — a non-governmental organisation. Main goals — elections monitoring and the formation of democratic institutions in Azerbaijan.

- US Embassy in Azerbaijan — America’s embassy in Azerbaijan.

- Gözətçi — a news site of Azerbaijan. The aim of the website is to collate information on human rights violations.

- Azadlıq Radiosu — the Azerbaijani service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- Human Rights Club — founded on Human Rights Day (December 10) in 2010 by a group of young Azerbaijani human rights advocates. The organisation’s main objective is to promote the protection and observance of human rights and fundamental liberties, as well as broader democratic development in Azerbaijan.

- Novator — a news site of Azerbaijan.

- BBC — the British Broadcasting Corporation’s service in Azerbaijan.

ANNEX 3: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (TAJIKISTAN)

- Radio Ozodi – the Tajik service of Radio Liberty.

- Reporters Without Borders – an international non-profit, non-governmental organisation that conducts political advocacy on issues relating to freedom of information and freedom of the press.

- Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) – an international non-governmental organisation.

- Akhbor – a news portal founded in Prague by the Tajik journalist Mirzo Salimpur.

- Asia-Plus– an independent news agency of Tajikistan.

- Jumhuriyat – the state newspaper of Tajikistan.

- NIAT Khovar – the national news agency of Tajikistan.

- Mediamarker.info – a media internet portal in the Tajik language, based in Poland.

- Payom.net – the news portal of the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan.