This story is part of the 2020 Investigative Grant Programme supported by the Justice for Journalists Foundation. The story was originally published on openDemocracy website.

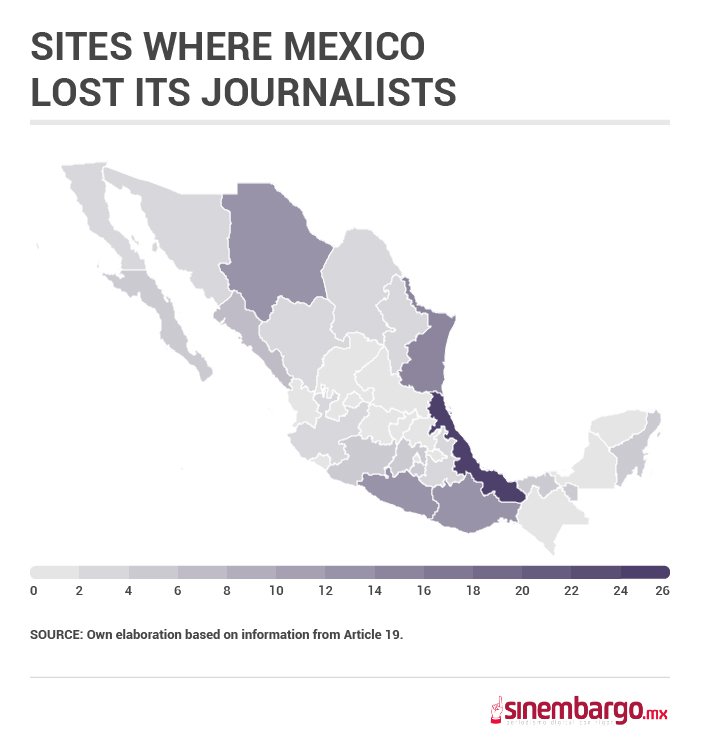

From 2000 to 2020, Mexico lost more than a hundred of its writers who were working without protection. Only Afghanistan and Syria, countries at war, have recorded more deaths of journalists. As a result, investigations into organized crime, poverty, siphoning off of public money, dispossession of indigenous peoples’ land by multinational companies, as well as the devastation of beaches, jungles and forests, have been cut short. Impunity has prevailed. So far, in more than 99 percent of the cases, there have been no convictions or sanction.

On February 1st, 2000, journalist Luis Roberto Cruz Martínez, from Multicosas magazine, was murdered in Reynosa, Tamaulipas. The murder suspect, Oscar Jimenez Gonzalez, was arrested and then disappeared. We still know nothing about what happened to him.

On May 16, 2020, journalist Jorge Miguel Armenta Ramos, owner of Grupo Editorial Medios Obson, which published the newspaper El Tiempo, was murdered in Cajeme, Sonora. He was leaving a restaurant when several people opened fire on him with different calibre weapons. Once again, we know nothing about them.

Between the first murder and the latest one, 131 others took place. In the middle of that timeline, on 23 March 2017, Miroslava Breach was shot dead while waiting in her truck for her son Carlos to go to school in Chihuahua, and at noon on 15 May 2017, Javier Valdez was shot dead in the middle of the street in front ofRio Doce, the newspaper he had founded years earlier in Culiacan, Sinaloa.

99.13% of the time (according to the organization Article 19 Mexico) we know nothing about who is behind the killings or why they happen.

The only thing that is clear is that the danger journalists face in Mexico is thanks to two main factors, one being the violence unleashed by the war against the drug cartels and the other being impunity. It is unclear which one takes precedence, and, in fact, they are co-dependent.

Why has this happened in Mexico?

11 states have laws that established protection mechanisms; two have links to the Federal Protection Mechanism created by the Ministry of the Interior. 11 states have unapproved protection initiatives and the remaining seven states have no proposed legislation.

Political scientists and journalists discuss the problem of violence against journalists, which in 20 years has taken more than 100 journalists’ lives. Only Afghanistan and Syria – countries at war – have registered more deaths of journalists.

In Mexico, journalists are being killed for a very simple reason, for doing their job. That is, because they tell the story of how organized crime, poverty, the embezzlement of public money, the dispossession of indigenous peoples’ land by multinational companies, and the devastation of beaches, jungles and forests by hotel and mining groups have taken over.

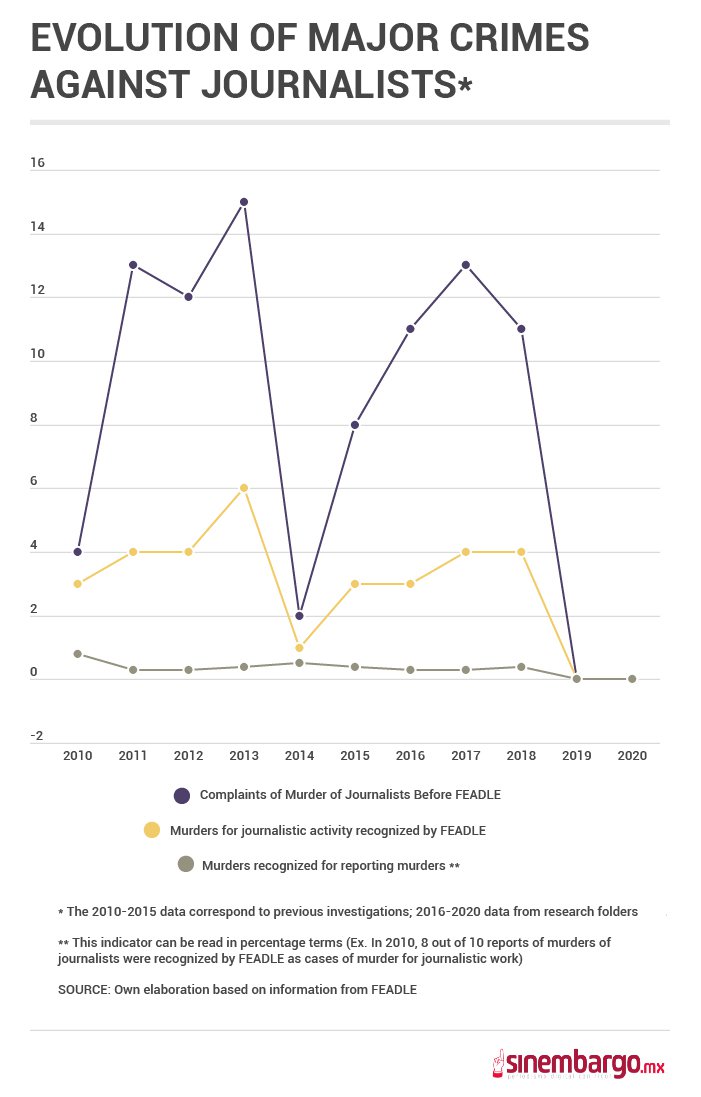

And there is no sanction. The decision to report threats to the Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against Freedom of Expression (FEADLE) or the local prosecutors’ offices is a vicious circle. The response is disregard, stereotyping, corruption and neglect.

The lives and deaths of those who died two decades ago have been lost with time. Searching for the traces of a journalist who died two decades ago leads to nothing, but a grave covered in mystery. The murders were not followed up by the authorities, the families moved away, and colleagues do not want to talk about many cases.

The war against drugs

In 2006, the Government of Vicente Fox Quesada created the Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against Journalists (FEADP) through agreement known as A/031/06. It was much needed. Fox’s six-year term was coming to an end. During the Presidential campaign Fox had offfered to establish guarantees for the defence and protection of human rights. And 24 journalists – professionals who, according to the former president’s speech, would no longer find themselves harassed for doing their job – had been murdered.

The FEADP was the first of its kind in the world. Its legal mandate was to protect, seek and prevent authorities and de facto powers from restricting or censoring “the voice of the people, public opinion and freedom of expression”. Octavio Alberto Orellana Wiarco was appointed by the then Attorney General Eduardo Medina Mora (now a fugitive from Mexican justice) as its head.

In July 2006, the presidential elections took place. Felipe Calderón Hinojosa, 43-year-old, was nominated by the National Action Party (PAN), the same right-wing political party that had nominated Vicente Fox Quesada six years earlier. In the vote count, something unprecedented occurred: the PAN candidate beat Andrés Manuel López Obrador, with just 0.58 percent of the vote. From that moment on, Lopez Obrador called him “Espurio”, a spurious rather than a legitimate President of Mexico. The nickname “espurio”, stuck and was echoed popularly.

“Espurio ” was an adjective that Felipe Calderón had to carry and deal with. Yet as a child, he has watched his father, side by side with political leaders such as Manuel Gómez Morín and Efraín González Luna, join a solidarity movement based on political ethics, human rights and an equitable distribution of wealth.

If words have any weight, “spurious” became a burden for Felipe Calderón Hinojosa. As such, he sought win confidence in his government. Quickly, less than ten days after taking office, he tried to justify a war against criminal groups as necessary. Soon, this moved on from being a plan to being policy, though later, he denied it was ” a war “.

But by then, it was too late. Mexico had become a battleground. The violence – which had been terrible – became more and more violent. Lives were shattered. Hopes were dashed. The drug trafficking business expanded at an unprecedented rate. And reporting – which aimed to reach out to those involved and tell their story – became a high-risk activity.

Enrique Toussaint, a journalist, and political scientist discovered a direct link between the beginning of that security policy and a chain of difficulties experienced by Mexican informants that often ended in death. “The very areas that were worst affected by this disastrous period are precisely those where journalism became impossible to practice. Michoacán and Ciudad Juárez were mirrors of the violence that began to cover the Mexican map”.

Balbina Flores representative of Reporters Without Borders in Mexico, agrees. “During the administration of Felipe Calderón Hinojosa, the violence against journalists that began under Vicente Fox intensified. It did not stop. It continued with Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018) and things are no better now, under Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

The perverse game of stereotypes

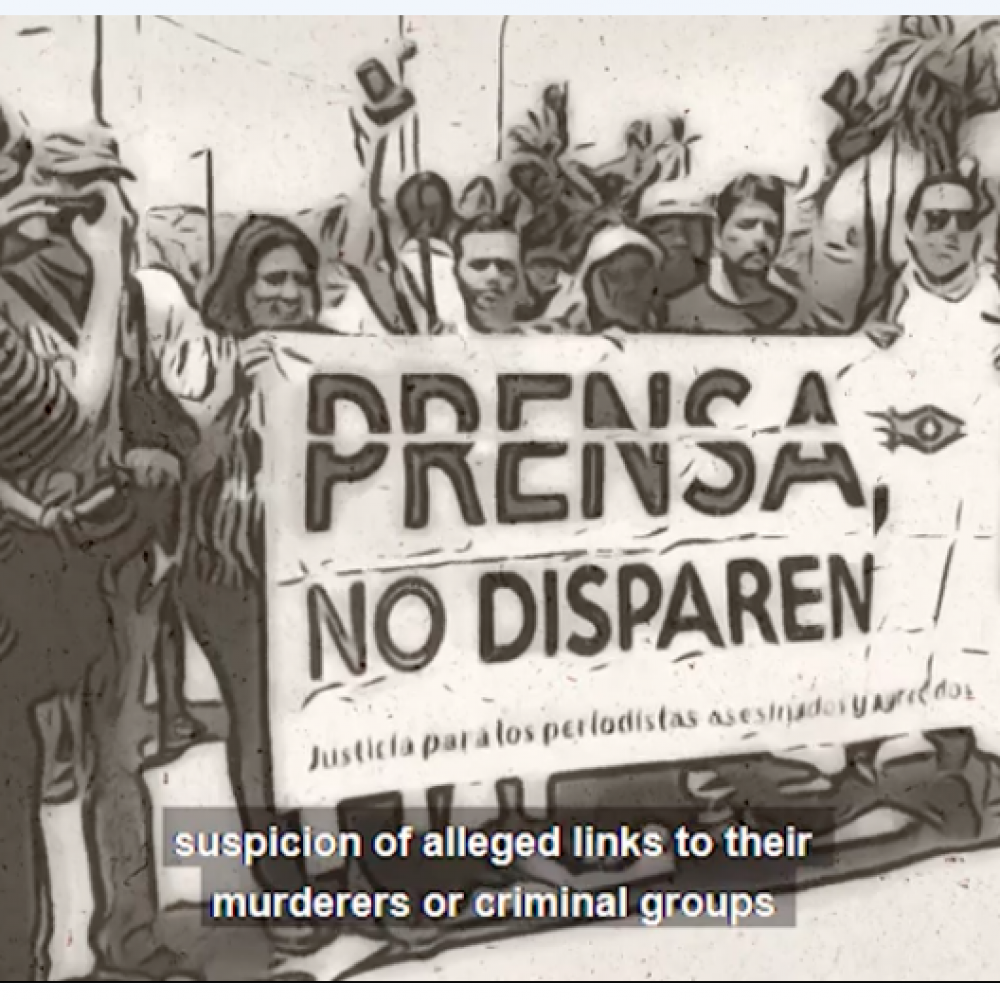

In 2008, the then Special Prosecutor for Crimes against Journalists (FEADP), Octavio Alberto Orellana Wiarco, mentioned three reasons why Mexican journalists are murdered: as a result of being threatened by drug trafficking gangs, after reporting on abuses of authority and because of alleged links of some of the journalists to organized crime.

In other words, journalists were being mixed up with criminals as the main reason for their death.

The mortality rate of journalists was high during under Vicente Fox Quesada (2000-2006), but the war against the cartels made it worse. And, from then on, the journalists who were killed were also stereotyped.

What was the point of investigating their deaths? What was the point of investigating why their investigations were suspended? What was the point of talking about journalism in Mexico? What was the point of talking about loss of life?

The organization Article 19 explains in the special report “Protocol of Impunity in Crimes against Journalists” that freedom of expression and journalism in Mexico became a an act of resistance, “threatened by different actors, including political, economic, criminal and governmental, journalists work every day without protection and at high risk to themselves.”

Researcher Oswaldo Zavala, author of the book Los carteles no existen,published in 2018, which broke new ground in the analysis of the drug industry in Mexico, says the violence experienced by journalists is carried out by “agents of the State”. He explains: “It is not just the police force. The violence ranges from threats to outright persecution”.

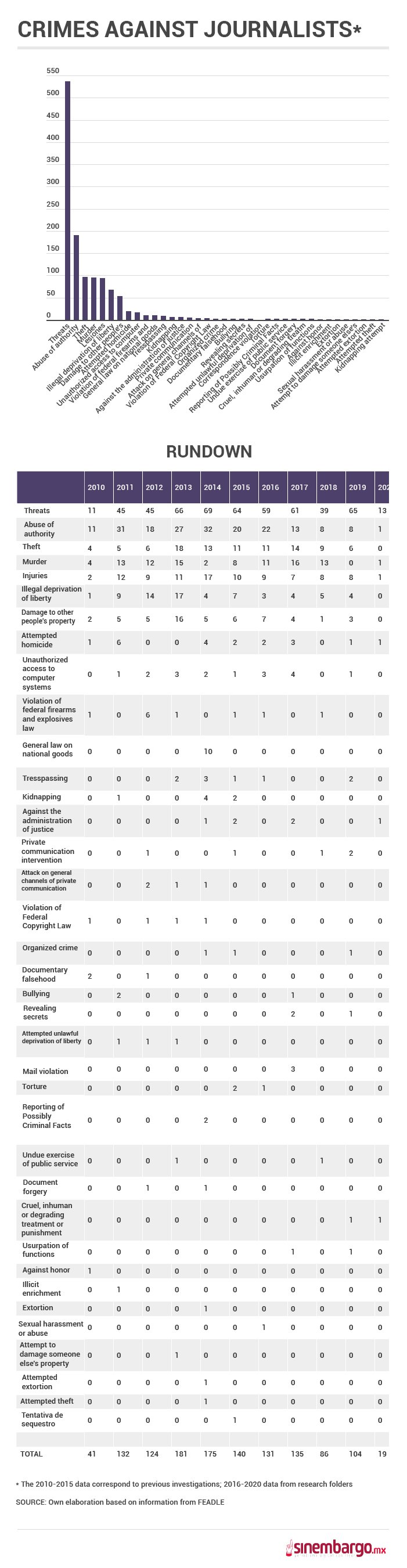

Whatever the reason, for journalists, death because part of the profession. In 2010, 58 s were killed. According to the FEADP report, Oaxaca was the state with the highest number of crimes against journalists, followed by Mexico City, then the State of Mexico and Tabasco and Tamaulipas.

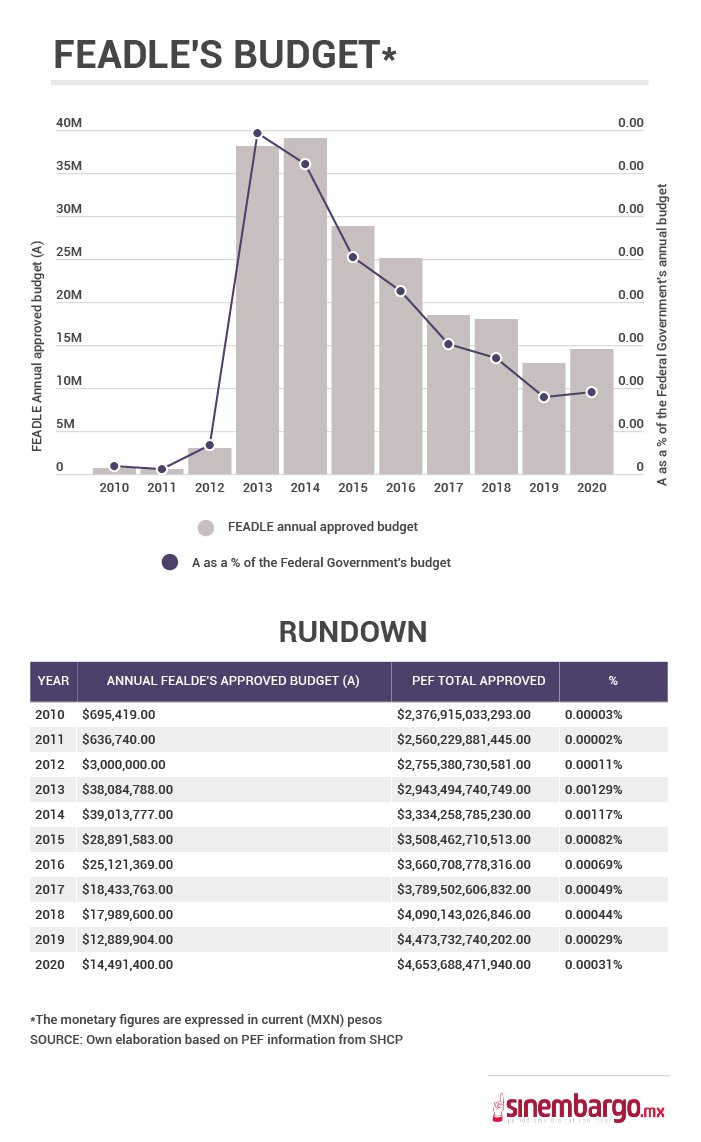

The government of then President Felipe Calderón Hinojosa accepted the need to transform the Public Prosecutor’s Office and d it did so with Agreement A/145/10, creating, the Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against Freedom of Expression (FEADLE).

The first Prosecutor was Gustavo Salas Chávez. He had been caught up in a scandal when in charge of Homicides at the Mexico City Attorney General’s Office, which had led to his dismissal on July 17, 2008., The newspaper Reforma had released a recording in which he was heard insulting several of his colleagues whom he called ” idiots’ and opportunists”. In the recording, he also set out his intention to become Deputy Attorney General’.

Salas Chávez had served as Director of Professionalization and Academic Extension at the General Attorney’s Office and, in addition, was the Delegate of the Mayor’s Office

(today called alcaldías) of Álvaro Obregón, Magdalena Contreras, Miguel Hidalgo, Cuajimalpa and Venustiano Carranza. He was also General Coordinator of the Specialized Public Ministry.

One year after his appointment, Gustavo Salas Chávez appeared before the First Permanent Commission of Congress. The FEADLE did not even have its own building. Salas Chávez said that at that time it had resolved “very few” cases because it did not have the necessary information.

He explained to Congress that there were cases that had not been classified as homicides because the victims had died in accidents, or they had not been acknowledged as journalists by the media owners, or because the cases were associated with organized crime. He resigned from office on 15 February 2012, having lasted barely two years as head FEADLE, two years.

Laura Angélica Borbolla Moreno took over. And the war carried on. It was clear that the strategy of dismantling cartels had not worked. New generations of criminals had emerged in Mexico. There were more than 104,000 dead, more than 14,000 missing and countless thousands displaced from their hometowns. This was Mexico in 2012.

Perhaps it started like this

In 1951, media owners and directors offered a dinner for the then President of the Republic, Miguel Alemán Valdés, at the Grillón restaurant. The national newspapers owed a considerable debt to the state paper company PIPSA, a monopoly company. In order to try and resolve the crisis, Colonel José García Valseca, owner of the Soles chain, brought newspaper and magazine editors together to ask the Government to condone or renegotiate the debt. The President responded with a complete cancellation of the debt.

The banquet, worthy of a prince, reflected the gratitude of these businessmen. Goose livers with champagne marmalade were served; eggs stuffed with Russian caviar; American lobster; Creole rice; Florentine ham timba; duck in Curaçao sauce; almond crepes were all served, along with 1946 Chablis wines and Charles Heidsieck champagne.

The historian of the Mexican Revolution, Martín Luis Guzmán, Colonel José García Valseca and businessman Rómulo O’Farrill all attended. In addition, the organizing committee included the Directors of Novedades, Alejandro Quijano; El Universal, Miguel Lanz Duret; Excélsior, Rodrigo de Llano; La Prensa, Mario Urdanivia, among others.

Martín Luis Guzmán wrote the invitation. “The Mexican press, made up of many serious and informative newspapers, weeklies and magazines, is indebted to the President of the Republic, Miguel Alemán. During the four and a half years since he became President, he has been a constant and scrupulous support for the freedom of the press, as well as freedom of thought and word,” read the invitation.

The singers Pedro Vargas and Toña La Negra performed, accompanied by Pedro García’s orchestra. They paused only for García Valseca’s speech: “Thank you, Mr. President, for the way you quickly resolved the paper shortage”. When Miguel Alemán Valdez left, the Colonel proposed June 7 as Press Freedom Day.

Two years later, the weekly newspaper Presente, run by José Piñó Sandoval, was closed. Presente had published reports on corruption in the German Government, and five journalists from Tiempo, run by Martín Luis Guzmán, were fired even though Guzmán had not published what happened on May 1st, 1952, when a opposition demonstration on Labor Day resulted in deaths and injuries.

Sixty years later, journalist Regina Martínez was found strangled at her home in Xalapa, Veracruz. A week later, the Naval Police found the tortured and dismembered bodies of Gabriel Huge, a former photographer for the newspaper Notiver, along with his nephew and photographer for the Veracruz news agency, Guillermo Luna; Esteban Rodriguez, who worked for Diario AZ; and Irasema Becerra, an administrator for the newspaper Dictamen. Huge and Luna were specialists in organized crime and its links with municipal and state officials.

In 2012, Journalist Marco Antonio Ávila García died in Guaymas, Sonora, and journalist Adrián Silva Moreno died in Tehuacán, Puebla. There have been more. As of today, there are a total of 133 deaths.

These journalists shared a common denominator: they worked without social security, using their skills to demand compliance with the law. Political scientist Enrique Toussaint argues that the fact that in Mexico, journalism has generally been in the hands of “millionaires” business owners, with interests in telecommunications, appliance stores and hospitals, has allowed for them to blackmail the Government, all of which which has threatened the human right of access to information. “Journalism has been an uncertain and precarious profession,” he points out.

Oswaldo Zavala, who worked in several Mexican newsrooms, adds an extra layer of analysis. “Journalists also suffer from daily, everyday violence from their own employer. The media are partners in the violence, and this is probably the most endemic, the most continuous and pernicious form of violence they face, because it has to do with exploitation at work, the absence of benefits, working in risky conditions and high level of demand being placed on reporters”, he said.

Appearing before the Mexican Congress in July 2012, Prosecutor Laura Angélica Borbolla Moreno said: “We have encountered behaviour that derives from a relationship or link to organized crime … either because something was published or something was not published.”

The return of the Revolutionary Party

The Institutional Revolutionary Party, led by Enrique Peña Nieto, returned to power in December 2012. The campaigns took place as thousands of students took to the streets to protest the media’s interference in politics and society. On December 1, when the President took office a crowd threw stones at buildings in Mexico City’s Historical Centre.

Even so, the international press painted an atmosphere of hope. The British magazine The Economist reported that the Mayan prediction of the end of the world had not been fully understood. It was not an extermination; it was a renewal. An awakening that was now led by Enrique Peña Nieto. The prediction faded away. In 2014, barely two years after his inauguration, 43 students from the rural school “Raúl Isidro Burgos” in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, disappeared.

From then on, the President’s credibility was broken. The Economist no longer claimed that Peña Nieto was capable of turning the tide of Mexico and questioned his political ability. In the streets, the cry became incessant: “The 43 are missing!” The polls were talking too. The politician who took his party back into government had the lowest approval ratings of any government in 20 years, 39 percent, according to the opinion poll in Reforma, and 42 percent, according to El Universal.

The President never mentioned the words “war”, “dead” or “disappeared”. This marked a departure from his predecessor, Felipe Calderón Hinojosa, though in fact, the war continued. Three newspapers said he preferred silence. In an editorial published on 11 March 2013 – in the first year of Peña Nieto – the newspaper Zócalo, from Saltillo, in the state of Coahuila, stated: “Since there are no guarantees or security for the practice of journalism, the Editorial Board of the Zócalo newspapers has decided, as of this date, to abstain from publishing any information related to organised crime. Our commitment is to increase our efforts to improve the quality of information and maintain objectivity and impartiality.”

Two other newspapers have also engaged in self-censorship, El Diario de Juárez in Chihuahua and El Mañana in Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas. Both agreed that if they continued with their work, the lives of their staff would be at risk. Each had suffered threats to their reporters and repeated attacks on their facilities.

The violence reached the headlines.

Jaime Guadalupe González Domínguez, reporter and director of OjinagaNoticias, in Chihuahua, was shot in his car on the afternoon of March 3, 2013. There were 18 gunshots. The newspaper was closed the next day. In other parts of Mexico, murders also continued. Alberto López Bello was killed on July 17, 2013 in Oaxaca and Gregorio Jiménez de la Cruz, kidnapped on February 5, 2014 in Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz.

Only Gregorio’s body was found. Jorge Torres Palacios was kidnapped by an armed commando on May 29, when he arrived at his home in a neighbourhood of Acapulco, Guerrero. Three days later, he was found inside a bag, decapitated and half-buried in a grave.

In August 2015, Arely Gómez, then Attorney General of the Republic, appointed Ricardo Nájera Herrera to lead the FEADLE. Nájera Herrera’s expertise was more in the area of communication than in police investigation: he graduated from the Faculty of Law of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, with a registered ID in 1980, and served as General Director of Communication for the Attorney General’s Office of Mexico City and General Director of Communication for the PGR.

Nájera Herrera had an uphill struggle. By 2017, FEADLE had achieved 97 percent ineffectiveness in investigating and prosecuting crimes. In April of that year, the Assistant Attorney General for Human Rights, Crime Prevention and Community Services of the Attorney General’s Office, Irene Herrerías Guerra, appeared before the Special Commission for the Follow-up of Aggressions against Journalists and the Media of the Senate of the Republic and presented the following information: between 2000 and 2017, 114 homicides had occurred, of which the specialized prosecutor’s office had only taken on 48.

It added that since the creation of FEADLE in 2010, 368 cases had been opened for threats against journalists, 159 for abuse of authority, 70 for injury, 70 for theft, 55 for illegal deprivation of liberty and 48 for damage to property.

She also said that, despite these numbers, only three prosecutions had taken place.

Three days before the murder of journalist Javier Valdez, Ricardo Nájera Herrera was dismissed. He was replaced by Ricardo Sánchez Pérez del Pozo. Until now, the Prosecutor’s Office has obtained 18 convictions, including those in two emblematic cases: the murders of Miroslava Breach Velducea and Javier Valdez Cárdenas, correspondents of the daily La Jornada. Eighty people are on trial and dozens of investigations are still under way.

**********

This article is part of a SinEmbargo.MX and democraciaAbierta research project, supported by the Justice for Journalists Foundation.