Zaborona published the first part of the investigation into the murder of journalist Pavel Sheremet. The investigation is supported by JFJ Investigative Grant Programme.

Journalists of Zaborona have received a document that reveals an important turn on Sheremet’s murder case.

In August 2016, a citizen went to the police. She said that her acquaintance Maksym Zotov personally confessed to her in the murder of the journalist.

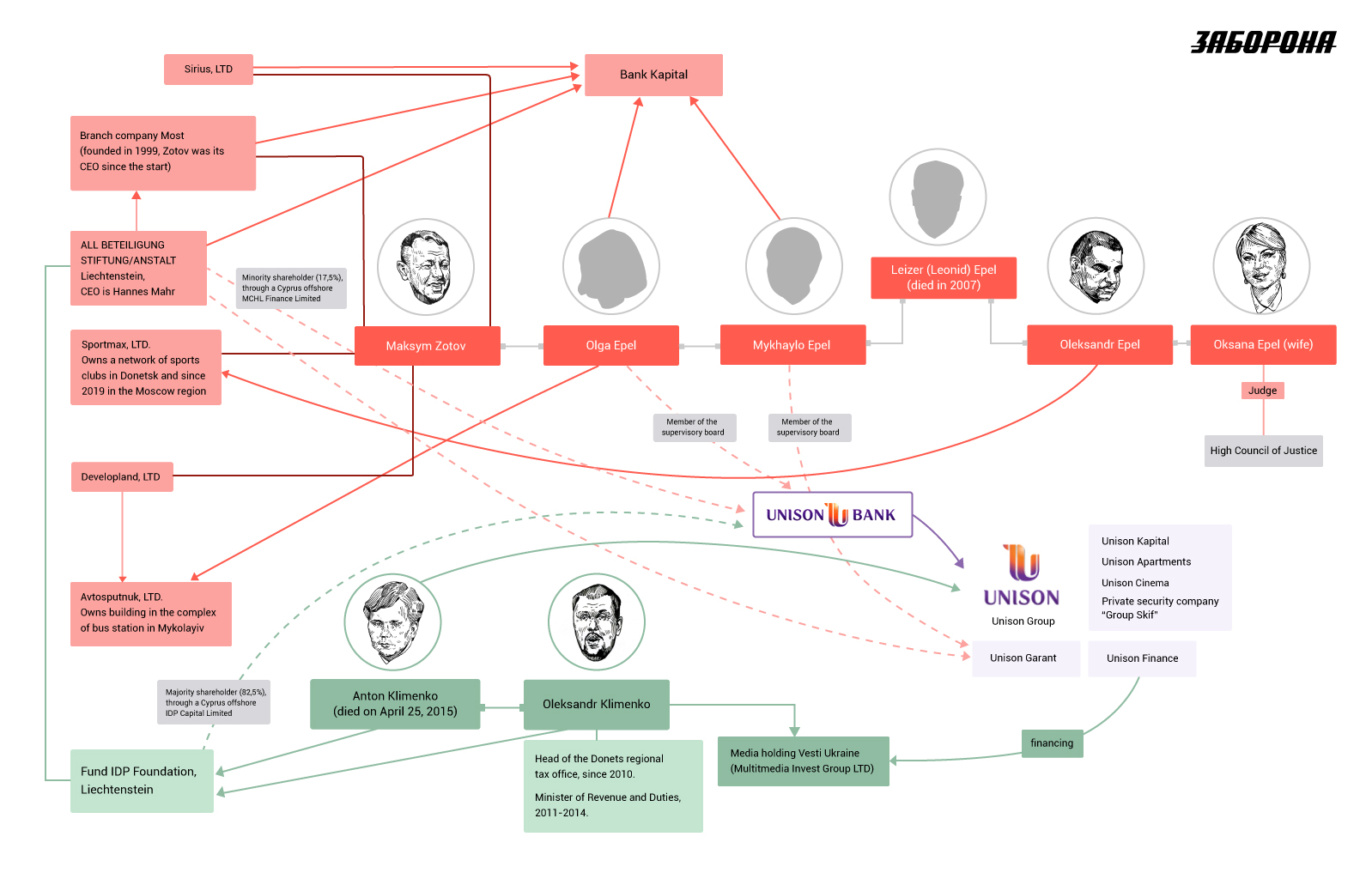

Maksym Zotov was born in Donetsk, strongly connected with former tax minister in times of Yanukovych presidency, fugitive oligarch Oleksandr Klymenko. In Ukraine, a criminal case has been opened against him.

Klymenko was the informal owner of Radio Vesti, where Pavlo Sheremet was an employee. A month before the murder, Pavlo went to meet Klymenko — he asked Pavlo to come up with a plan for his return to Ukraine.

A witness from Mariupol

It was three weeks after the murder of Sheremet. For unclear reasons, the bombing of the journalist’s car had not, unlike many similar cases, been qualified as a terrorist attack, so the investigation was entrusted to the police.

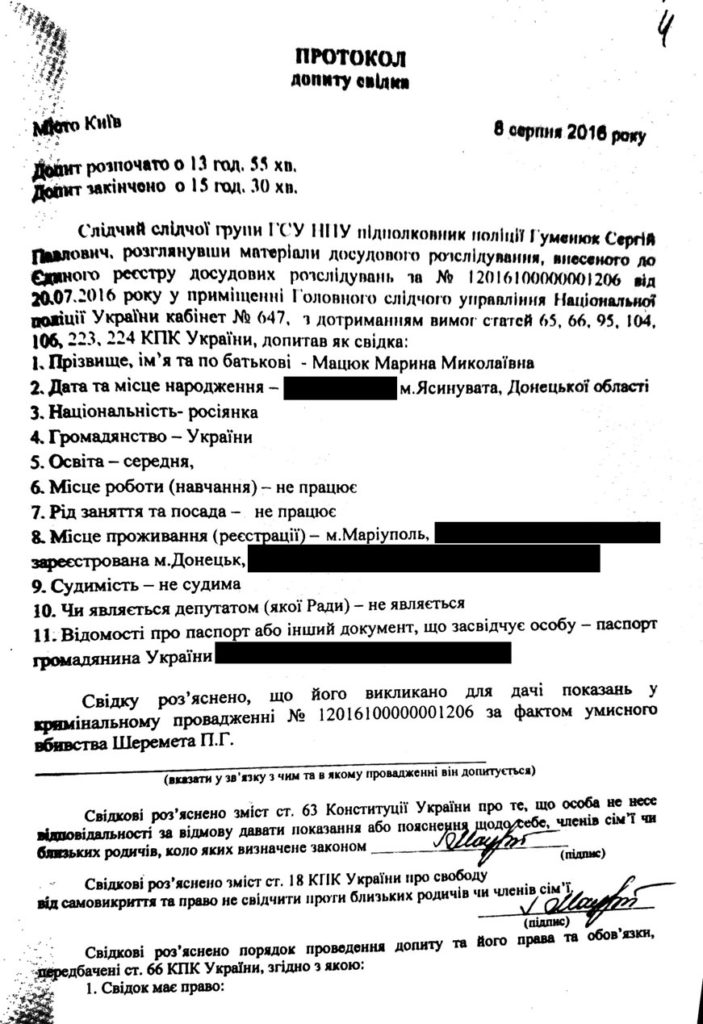

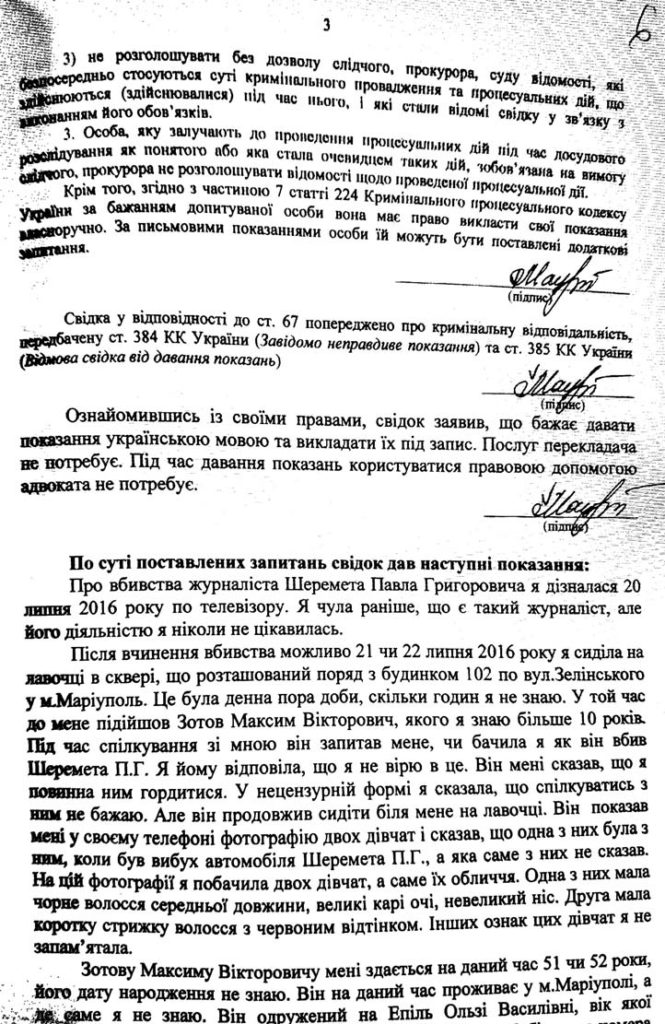

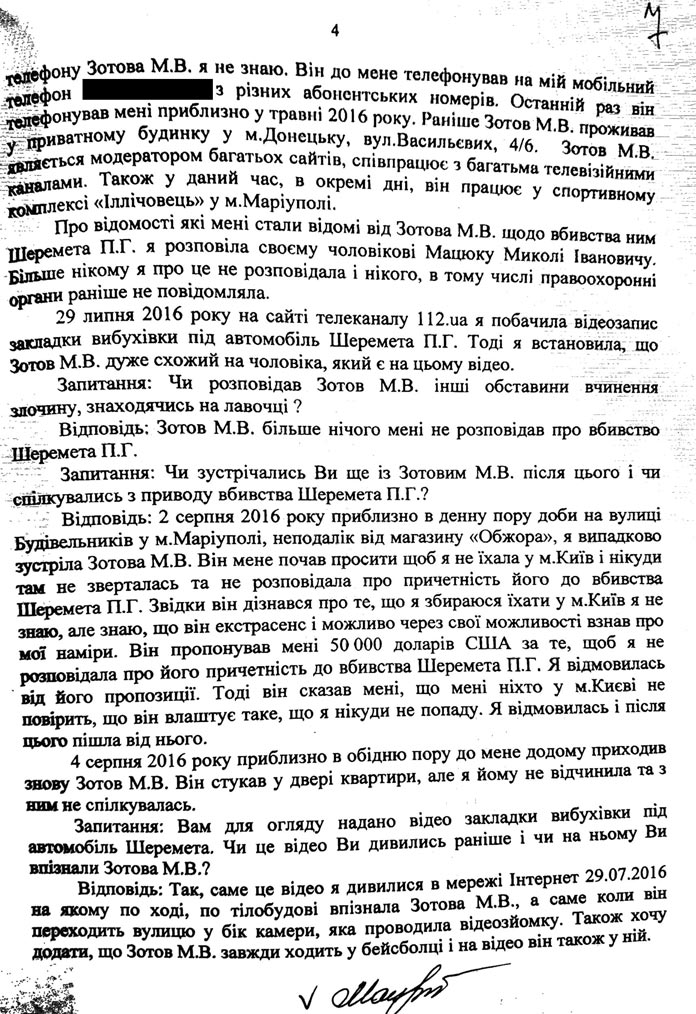

On Monday, August 8, 2016, Maryna Mykolaivna Matsyuk, an internally displaced person who had moved from Donetsk to Mariupol after the outbreak of the war, came to the headquarters of the National Police in Kyiv. She said that around July 21st-22nd, when she was sitting on a bench near her home in Mariupol, a man named Maksym Viktorovich Zotov approached her. According to Matsyuk, they had known each other for over ten years. In support of her words, she gave his home address in Donetsk. It was a private mansion, which was located about 50 meters from the high-rise building where Matsyuk had lived with her family.

According to Matsyuk, the conversation developed as follows. Zotov asked if she had seen how he “killed Sheremet.” She replied that she “did not believe him.” In response, Zotov said that she “should be proud of him” and, according to her, showed a photo on his phone, which showed two girls. Zotov said that he was with one of them when the explosion of Sheremet’s car took place. Who it was, he did not say.

Soon, on August 2, according to Matsyuk, she walked along Stroiteley Street in Mariupol, and not far from the Obzhora store (probably, we are talking about the Obzhora shopping center on 125 Stroiteley Avenue, renamed M-center last year) she met Zotov by chance. He “began to ask not to go to Kyiv or anywhere else, and not talk about his involvement in the murder of Sheremet.” Matsyuk told the investigator that Zotov allegedly offered her 50 thousand dollars so that she would not talk about his involvement. After the woman refused, he said that “no one in Kyiv would believe her, and that he would make it so that she could not go anywhere.” On August 4th, Matsyuk claims, Zotov came to her house in the afternoon and knocked on the door, but she did not open it.

Matsyuk clarified that on July 29 she saw on Channel 112 a video (probably this one) of how the explosives were placed under Sheremet’s car. It seemed to her that Zotov looked very similar to the person in the video – in gait and physique, namely at the moment when he crossed the street towards the security camera. Matsyuk also added that Zotov always wears a baseball cap, and in that video “he was also wearing one.” This is where her testimony ends, and her signature is under the clause on criminal liability for giving deliberately false data.

Despite the loud and rather detailed statement, the investigators did not stick with the testimony of Maryna Matsyuk or investigate further. With other similar testimonies, including the most credible ones, they acted differently. According to the materials of the investigation, Interior Ministry employees undertook efforts to track down the sources of anonymous reports about alleged suspects. The sources, as a rule, turned out to be people who had made their own conclusions about those who ordered the murder from what they had heard in the media, or simply mentally ill people. Also, the police quite thoroughly researched publications in the media and interviewed journalists.

In the case of Matsyuk, the investigation did not go beyond a couple of requests for more information. There are not so many men named Maksym Viktorovich Zotov from Donetsk – only one. In 2016 it was quite easy to find him – as well as to verify the testimony of the witness.

But that’s not all. Matsyuk not only gave Zotov’s address, but important details. For example, she confirmed that he is married to Olga Epel, a woman from a very influential Donetsk family. This fact should immediately give a signal to the investigation that the testimony has serious grounds. And here’s why.

Oleksandr, our dear man

The Epeli’s are an influential Donetsk business family. Olga Mikhailovna Epel owns a trucking company, construction companies, investment funds, cars, real estate, and is a shareholder of some large financial organizations. Until mid-2013, her father, Mikhail Epel, served as chairman of the board of Kapital Bank, and then joined the supervisory board of the Unison-guarantor insurance company, still having majority control over Kapital. Both companies became widely known in connection with the high-profile case initiated in 2014 against the fugitive Minister of Revenue and Duties Oleksandr Klymenko. But first things first.

At the time when Viktor Yanukovych became president of Ukraine in 2010, the Epel family maintained friendly relations with many Donetsk businessmen who came from the Industrial Union of Donbass (ISD) group and the Klymenko brothers. Anton Klymenko’s group of companies Antalex was serviced by Bank Kapital. (Anton, the elder brother of Oleksandr, died under mysterious circumstances in 2015). It was a mutually beneficial relationship: in the fall of 2010, Oleksandr Klymenko became the Deputy Head of the State Tax Administration in Donetsk oblast and, taking advantage of his position, helped his partners and his brother build a business empire. The Prosecutor General’s Office would come to call this friendship a conspiracy, thanks to which billions of hryvnias were laundered through Kapital Bank from 2011 to 2017 in the interests of Epel’s clients, primarily Klymenko and the Yanukovych family.

All these companies, as well as Mikhail Epel himself and companies associated with him, figured in a high-profile case initiated in 2014 against the fugitive minister Oleksandr Klymenko. The new Ukrainian authorities suspected him of creating a corruption scheme that allowed the circle of President Yanukovych to earn billions on illegal VAT refunds. This was confirmed to us by the prosecutor of the GPU, Sergiy Gorbatyuk, who initially conducted the case.

Matsyuk, the witness in the Sheremet case, told investigators that she had known Zotov for ten years. An attempt to get any confirmation of this acquaintance was unsuccessful – Matsyuk told our Zaborona correspondent that she had a wrong number (the audio recording is at the disposal of Zaborona). However, according to lawyer Andriy Leshchenko, representing the interests of the Sheremet family, he had called Matsyuk on the same phone earlier, and in a conversation with him, when asked to tell more about the events of July-August 2016, she stated that “everything is in the case file” and declined to comment further (the audio recording was also made available to Zaborona).

We confirmed that before the war, Matsyuk had indeed lived in a high-rise building, located in the immediate vicinity of Zotov’s house. Her husband held the modest position of head of the personnel department in the Donetsk Department of the Penitentiary System of Ukraine (DPS). In the summer of 2014, after the seizure of the traffic police building in Donetsk by separatists, the family was evacuated to Mariupol, where they stayed in the summer of 2016. The address where the Matsyuk family lived there coincides with the address that Maryna Nikolaevna described in her testimony to the investigator. Residents of neighboring apartments confirmed this to our Zaborona correspondent (the audio recording is at the disposal of the editorial office).

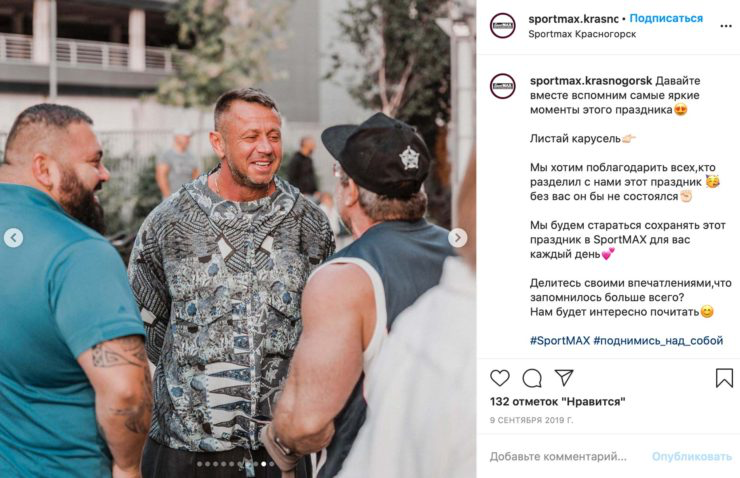

Zotov was a bird of a completely different flight. He is the founder and owner of the SportMax sports club network in Donetsk. The company was registered in 2007 and stands for “Sports Maksym”. The network was perhaps the most popular in Donetsk and played a significant role in the city’s sports infrastructure. For example, there is a video from 2012, where immediately after the European Football Championship, the mayor of Donetsk, Olexandr Lukyanchenko, thanks SportMax for the construction of the whole complex with the stadium. Zotov’s fitness clubs have not ceased to exist in the self-proclaimed DPR: the network has a website, an Instagram page showing the club’s activity, and the company has been re-registered with the tax authorities of the occupants.

The manager of Sportmax and the co-founder of the public organization “Sports Union Sportmax ” was the multi time champion of Ukraine and the world in MMA Bohdan Khmelnytsky. Khmelnytsky and Zotov, after the start of the war in Donbas, created the TV show “White Collar Fights”, where professional wrestlers teach young people to fight without rules. For this show Khmelnytsky traveled to many Russian cities. And the fact that Zotov is a co-creator of the show is stated in the credits of each episode.

At one time, the general director of Sportmax was (for example, in the same video from the opening of the complex in 2012) Oleksandr Leizerovich Epel, the brother of Mikhail Epel. And the phone number to which the company was registered coincided with the number to which two companies of Anton Klymenko were registered – Unison Cinema and Unison Group.

Maksym Zotov is not on any social networks, and his photos cannot be found in a regular search query. He rarely appears in public. However, we managed to find several of his photographs. Here he is in a photo posted on June 17, 2018 by Bohdan Khmelnytsky, along with an athlete in front of the OZ Mall in Krasnodar.

A little later, on October 25th of the same year, he was photographed with Khmelnytsky and Vsevolod Zaraisky (more about him a little later) in the elite village of Barvikha, Moscow Region, against the background of his car on Donetsk plates. The car, by the way, is a Mercedes S500 L worth about 100 thousand dollars, and it is registered at the address of Zotov in Toretsk (before decommunization – Dzerzhinsk), Donetsk region. This is not Zotov’s only executive-class car: it officially lists another Mercedes E 220 D worth about $45,000. And behind the “Developland” company owned by him and his wife – several more “Mercedes” SUVs of the same price category.

According to information from official sources, Zotov moved from Ukraine to the Moscow region. In September 2019, we found him in a photo report from the opening of the SportMax fitness club in Krasnogorsk, a satellite city of Moscow. In the Russian registries, he is listed as the owner of the club, and registered the company in May 2019. Our Zaborona correspondent confirmed Zotov’s connection with SportMax. And here are his photos from the opening of the club.

Maksym Zotov is not just the son-in-law of the former defendant in the Klymenko case. He himself is close to the fugitive oligarch – so much so that once he even starred in his role. The chanson group “3:15” has two videos for the same song “Alexandr”, released in early 2013. In one version, Maksym Zotov plays a busy day and night politician who lives between Moscow and Kyiv. One of the first frames in the video is the Moscow City office center, where Klymenko received Pavel Sheremet. Zotov is even dressed up as Klymenko.

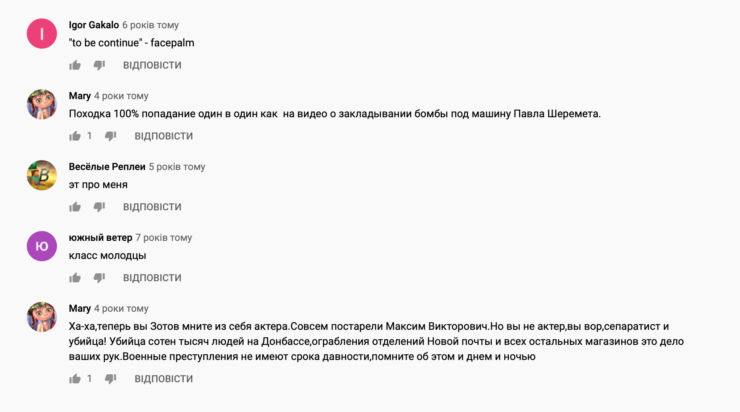

And in another version, the clip is about boxing. In March 2013, a boxer and deputy of the State Duma of the Russian Federation Nikolai Valuev flew to Kyiv for filming. The plot revolves around the preparation for the fight in the ring. Valuev played the role of a coach, and the role of a hero-boxer was the same Zotov. Below the video you can find two comments left by a user with the username Mary. “The gait is 100% one-on-one as in the video about planting a bomb under the car of Pavel Sheremet,” says the first comment, left in 2016, three years after the video was published.

Mary’s second comment is more lengthy: “Ha-ha, now Zotov, you pretend to be an actor. Maksym Viktorovich has grown quite old. But you are not an actor, you are a thief, a separatist and a murderer! The murderer of hundreds of thousands of people in Donbass, the robbery of Nova Poshta offices and all other stores is the work of your hands. War crimes have no statute of limitations, remember this day and night.”

Maryna Matsyuk, who brought charges against Zotov, is engaged in amateur photography, using the nickname Mary M on some websites. And the robbery of the courier service department of Nova Poshta in Donetsk took place on July 7, 2014 – the day after the seizure of the Donetsk department of the Penitentiary Service of Ukraine by militants, where her husband Mykola Matsyuk worked.

Sportsman and businessman

However, Zotov is not just a physical education instructor and entertainer of the Epel-Klymenko clan. We discovered that since 1999 he has been the head of the Ukrainian subsidiary of the Liechtenstein fund, which is behind the Unison Bank.

Zotov married Olga Epel in 1997. Her father Mikhail Epel was already a rather influential Donetsk businessman then. He was a member of the Industrial Union of Donbas group, was a business partner of the Shcherban family, influential in Donbas, in Kapital bank, and at the Donmet plant he dealt with Givi Nemsadze, a man who was accused of involvement by Ukrainian law enforcement agencies from 2005 to 2010 of 57 murders and the organization of a criminal community, but after five years on the run, which ended in a voluntary appearance, he was acquitted by the court.

Maksym Zotov gradually became a full-fledged part of the Epel clan: over time, he was entrusted with the management of the most important assets, for example, Sirius and Most companies, which are the key shareholders of Kapital Bank and founders of most of the family’s companies. In addition, Most is a Ukrainian subsidiary of the Liechtenstein company ALL BETEILIGUNGS STIFTUNG, which plays a very important role for Epel and Klymenko. Together with members of the Board of the Kapital Bank, Zotov creates companies engaged in video production, television and gambling (the full dossier can be viewed via YouControl).

Even Zotov’s employees in Sportmax fitness centers became managers and signatories of the Epel family companies. So, all three directors of the Ukrmostcompany, connected with the sale of natural gas and fuel, are SportMax coaches (two of them still work in the club in the occupied Donetsk), and in some companies, the management top was, for example, kickboxers and MMA fighters.

Maksym Zotov’s friend, kickboxer Vsevolod Stanislavovich Zaraisky, in July 2019 became the final beneficiary of Epel’s Asset Management Company Business Invest LLC – Zotov transferred the company to him. Interestingly, in July 2016, this company figured in the SBU case on the financing of terrorism in the occupied territories of Donbas. Zaraisky appears together with Zotov and Khmelnytsky in a photo from Barvikha near Moscow. In the caption of the picture, Khmelnytsky writes that they are “brothers in blood and spirit.”

The investigation did not consider it necessary to investigate or even establish the connection between Maksym Zotov and Epel and Klymenko. This is especially strange in light of the fact that the investigation team at one time considered the possibility of Klymenko and his common-law wife Olga Semchenko being implicated in the murder. Representatives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the military prosecutor’s office have repeatedly voiced this version in the media (for example, here). This is evidenced by a number of documents in the case. For example, there are instructions to the head of the Criminal Investigation Department about the need to call Semchenko in for an interrogation, printouts of her movements across the border, interrogations of Radio Vesti employees. Investigators also examined Klymenko’s connections with companies and individuals that own the Vesti Ukraina media holding. However, they apparently did not try to compare this version with the statement of Maryna Matsyuk regarding Maksym Zotov.

Official representative of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Artem Shevchenko, said to Zaborona correspondent that “his [Sheremet’s] repeated stay on the territory of the aggressor country of Russian Federation at different times, including the last months before his death, and contacts with Klymenko was certainly of interest to the investigation. But the investigation is deprived of such an opportunity due to the lack of cooperation with the law enforcement agencies of the aggressor country, which is quite logical”. Shevchenko also said that he didn’t know anything about the existence of evidence against Maksym Zotov.

We tried to contact Klymenko through Olga Semchenko, but she refused to forward information and said that he don’t have a press secretary.

We also repeatedly passed on a request to speak with Maksym Zotov through his sports club near Moscow and his friend, Bogdan Khmelnitsky. However, he didn’t consider it necessary for us to answer.

Return plan

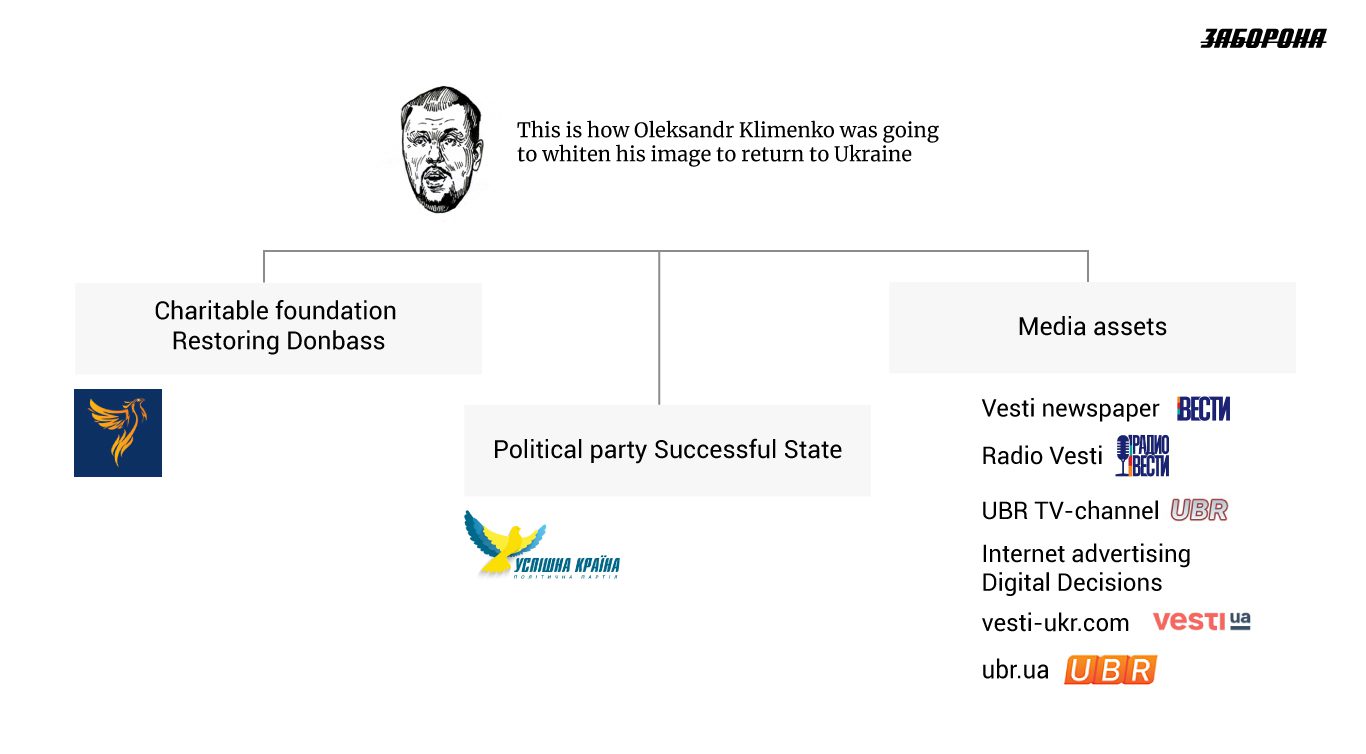

In 2013, Oleksandr Klymenko, being the Minister of Revenue and Duties, initiated the creation of the Vesti Ukraina media holding, which included the newspaper of the same name, the Vesti Reporter magazine, the UBR TV channel and Vesti radio. For a long time, Ihor Guzhva was the general director of the holding, and the editorial staff did not know who the real beneficiary was. However, this became clear at the end of 2015, when Olga Semchenko, the common-law wife of Oleksandr Klymenko, took the place of Guzhva. Before that, Olga was his press secretary, when he was still in charge of the department for work with large payers of the Tax Administration of the Donetsk region, and later the speaker of the new Ministry of Revenue and Duties

According to Zaborona source close to Semchenko, it was she, together with her ex-husband, political scientist Alexander Semchenko (who previously headedthe Ministry of Revenue Department in the Sumy region), proposed to Klymenko a plan to return to Ukraine.

When Semchenko took over the holding, some employees began to oppose this appointment. For example, the former journalist of Vesti Reporter magazine Svetlana Kryukova said in an interview to Detector Media directly that during this period the participation of Oleksandr Klymenko became obvious, as did his goal – to use the media holding for political struggles. Olga Semchenko deniedthis and said that Klymenko did not influence the editorial processes.

In December 2015, Klymenko announced that he was becoming the honorary chairman of the Uspishna Kraina party and was going to go with her to the by-elections and re-elections to the Verkhovna Rada, which were predicted for the fall of 2016.

At that time, Pavel Sheremet had been working on Radio Vesti for six months as a host of Saturday Air. According to Olena Prytula, this had been his main source of income since he left the Russian OTR TV channel in the summer of 2014.

Despite the fact that Pavel worked as the executive director of Ukrainska Pravda, he received a symbolic salary in the editorial office – in order to be able to obtain a residence permit in Ukraine. According to Prytula, he did not earn anything in the publication “Belarusian Partisan”, the founder and leader of which was Sheremet. Relatives do not specify the amount of how much Sheremet earned at Radio Vesti, but we know from former employees of the radio station that some presenters were paid about 100 thousand hryvnias per month (more than $ 4000 as of June 2016).

In the spring of 2016, the PR campaign of the Uspishna Kraina party began to gain momentum. On the air of Radio Vesti, according to the then chief editor of the information service Saken Aimurzaev, representatives of the Klymenko party began to appear more and more often. The mood in the editorial office became more and more gloomy: many, he says, understood that the media was being made the mouthpiece of a fugitive politician.

Aimurzaev recalls that in February a Skype conference was held at the radio station with Oleksandr Klymenko himself, at which the management of all publications of the media holding was present (and this was confirmed by other employees of the holding). During this call, the politician made it clear that the media is his instrument of returning to power. “I realized that he was a very tough person, stubborn, and wanted to have influence,” Aimurzaev said in an interview with Zaborona.

From a source close to the then management of the radio, Zaborona learned that representatives of the top management of the media holding in the spring went to a working meeting with Klymenko in Sochi, where they discussed media development.

At the end of March 2016, Aimurzaev said on the air of Vesti that he and Sheremet were leaving the radio station, not wanting to observe the degradation of the media and endure the antics of the real owner. Sheremet criticized him for this act. “Pasha stayed on the radio and did not leave,” Aimurzaev says. “He even updated his show. I had a feeling that if he became the head of the radio station, he would return me there too. Who knows, I thought, maybe Pashka will manage to maintain the editorial office and its independence.”

Unsuccessful negotiations

On June 10, Pavel Sheremet went to Moscow. He had family lived there – his children and ex-wife. His daughter Liza told Zaborona in a telephone interview that Pavel, as usual when he arrived, had several tasks: he was going to celebrate her 20th birthday and meet with colleagues and friends from the circle of Boris Nemtsov, who was assassinated in 2015 (for example he met with Vladimir Kara-Murza).

However, there was one more goal that he voiced to his daughter in passing: Sheremet was in a hurry to meet with the “fugitive oligarch” – as he called him – Oleksandr Klymenko. The meeting was to take place in the Moscow City office center, where Klymenko, according to some sources, owns an entire floor. It is not surprising that views of Moscow City appear in the clip “Alexander” with Zotov in the title role.

Pavel’s ex-wife Natalya Sheremet claims that Sheremet told her that he planned to negotiate with Klymenko to become the head of the radio station. “Talking to owners, investors is a matter of principle and [ultimately] doing radio,” she recalls.

On the way, Sheremet brought his daughter to the Afimall shopping center. According to Liza, he was agitated, unusually “on edge” and, “it seems, even violated the traffic rules.” At the same time, according to her, he was not frightened: seeming “on edge”, rather, indicated that he had something important planned, which made him worried.

Sheremet’s widow Olena Prytula told Zaborona that Pavel traveled to Moscow in order to negotiate with Klymenko about the appointment as editor-in-chief of Vesti. Sheremet told her that he wanted to “understand the mindset of Klymenko” and assess what kind of future their editorial office could expect. Prytula also says that Klymenko wanted to talk to Sheremet about whether the journalist could help him find a way to return to Kyiv.

Sheremet really had ambitions to head Vesti. Prytula knew about this, and his friend and colleague on the radio Saken Aimurzaev, and his ex-wife Natalya. All three confirm that Pavel was ready to work in the media organization, which was owned by the fugitive minister, provided that they did not interfere in editorial policy.

“Pasha believed that Klymenko wanted to return home [to Ukraine],” Prytula says. “He offered him his own solution – something that would set the stage for his return – open, democratic, honest radio.” However, Pavel returned from the meeting unsatisfied. “It was unpleasant for him to talk about it, he did not achieve his goal,” says Prytula.

According to her, after returning to Kyiv, Sheremet repeated the same phrase about Klymenko several times: “He has Orthodoxy of the brain, it is useless to talk to him. He didn’t hear me, he didn’t understand what I was talking about, he didn’t understand who I was. ” Sheremet’s quote about the “Orthodoxy of the brain” by Klymenko was also later cited by the military prosecutor Matios, who met with the journalist a few days before his death and was considered as Sheremet’s friend. We will tell you more about this in the second part.

Several days after returning from Moscow, Prytula recalls, Pavel was upset. But he continued to work on the radio anyway: “I woke up with great enthusiasm at 5 am, prepared for the broadcast, was very energetic, thought over the broadcast scripts, worked with pleasure.”

“Usually, when Pasha returned [from Moscow], it was fireworks,” says Saken Aimurzaev. “He told who he saw, with whom, what he talked about. And then suddenly he became very closed. I remember the story of how he went to Klymenko. He said that the office was in Moscow City, that there were many icons and a chapel. But in essence he didn’t say whether they had agreed on anything, nor even conveyed a general impression”.

Shortly after that Moscow meeting on Radio Vesti, there was a big conflict. A new editor-in-chief was appointed – Irina Gavrilova.

“Pasha understood that his days on the radio were numbered,” says Prytula. “He realized that his concept was of no interest to anyone, that things were moving towards curtailing freedoms on the radio, which, in principle, happened.”

In early July, Vesti journalists signed an open letter against the appointment of Gavrilova, as she publicly spoke out insultingly against the Maidan participants and volunteers of the war in Donbas. The next day she was fired. The original letter was published by various Ukrainian publications. Sheremet’s signature was not there.

Early in the morning of July 20, Pavel Sheremet went to his morning broadcast on Vesti radio. At 7:51 a home bomb exploded in his car.

Many employees of the radio station came to say goodbye to him at the Ukrainian House. Among them, Aimurzaev recalls, was Klymenko’s common-law wife Olga Semchenko. According to Liza Sheremet, on that day she was handed an envelope with money, allegedly collected by the staff of the radio station. There were 20 thousand dollars in the envelope. Saken Aimurzaev, acting as an intermediary, claims that Semchenko had transferred the money.

Soon after Sheremet’s death, the PR campaign of Klymenko’s party came to naught, and early parliamentary elections did not happen that fall. The holding gradually began to curtail the work of the editorial offices, and soon only the newspaper and the website Vesti and UBR remained of it. The broadcasts and news that aired on Vesti radio are currently unavailable.

Stranded in Mariupol

In July 2014, DPR militants seized the building of the State Police Service (Penitentiary System of Ukraine) in Donetsk. Like other employees, the chief personnel officer and trade union leader of the Donetsk administration, Mykola Matsyuk, together with his wife Maryna, were forced to evacuate to Mariupol, which was itself on the front lines of the war. By 2016, the situation had stabilized, but then the Donetsk jailers suffered a new blow from fate.

On May 18th, the Ukrainian government announced the liquidation of the State Police Service as part of a large-scale reform of the penitentiary system. In practice, this meant that all employees of the country’s system had to be fired from the liquidated structure, and only a part of them would find a job in the new one.

On June 10th, the staff of the State Fire Service Administration in the Donetsk region addressed an open letter to the President, the Government and Parliament of Ukraine. It says that in connection with the reform, all employees of the department, 39 of whom had the status of persons displaced from the occupied territory, were threatened with “losing their only source of income for their families”.

At the same time, the appeal said, the authorities had not taken into account that the officers of the State Police Service remained faithful to their oath, although they had had to leave their homes, and some of them “were captured by representatives of the illegitimate armed formations of the so-called DPR, where they were subjected to moral and physical pressure” … They, the letter says, continued to live in Mariupol on a modest salary, without any benefits and even without the status of ATO participants.

This test ended differently for the Donetsk jailers. For example, Mykola Matsyuk’s boss, the head of the Donetsk department, Alexander Zamiralov, lost his post. From press reports it is clear that since August 2016, he was replaced by acting head Dmitry Nemtsev. Zamiralov found work in the security of the Mariupol port, but, as he told our Zaborona correspondent in a telephone conversation, he has recently lost it. He declined to comment on the events of 2016.

But for Matsyuk himself, things went sharply uphill. According to the declarations of the National Agency on Corruption Prevention, in 2017, he and his wife Maryna had already moved to Kyiv and worked in the apparatus of the structure created from the ruins of the State Penitentiary Service of Ukraine – the State Criminal Executive Service of Ukraine (SCES). By 2019, he became the head of the personnel department of the administration of the All-Ukrainian State Property Committee, at the same time being the head of the personnel trade union.

The apartment where the Matsyuk family lived in 2016 is now being rented out to other residents. Opposite the entrance there is one shop – probably the one that Maryna Matsyuk described to the investigator. One of the neighbors at the entrance told our Zaborona correspondent that shortly before the Matsyuks had left for Kyiv (which happened before the beginning of 2017), two men in suits visited her and asked about her family. She says the men showed the IDs of law enforcement officers. They did not remember which department exactly.

Mykola and Maryna Matsyuk ignored all Zaborona’s requests to explain how they knew Maksym Zotov and whether they still consider him a possible organizer of the murder of Pavel Sheremet. Realizing their possible risks, Zaborona was ready to anonymize them in this publication, which was also brought to their attention. However, Mykola Matsyuk, when asked by Zaborona to confirm or deny the situation described by his wife, refused, adding that he “doesn’t care” whether this fact will emerge in court. The refusal to communicate in a conversation with journalists reinforces our suspicions that they could have been either intimidated, or used to mislead the investigation, or to put pressure on Oleksandr Klymenko.

Unable to talk to the Matsyuks, we asked ourselves who could influence their fate and at the same time was so well acquainted with the activities of the completely non-public Epel family and Maksym Zotov himself to bring his name to the Sheremet case. Studying the characters who received access to the Klimenko case in the summer of 2016, where Zotov’s father-in-law Mikhail Epel was involved, we found many interesting connections and circumstances that confirm our version that the murder of Sheremet was highly likely related to the case of the fugitive oligarch.

The second part is coming soon.