PHOTO: CITIZEN JOURNALIST RUSTEM OSMANOV (THE CRIMEAN PROCESS)

AUTHOR OF THE REPORT: HUMAN RIGHTS CENTRE ZMINA

1/ KEY FINDINGS

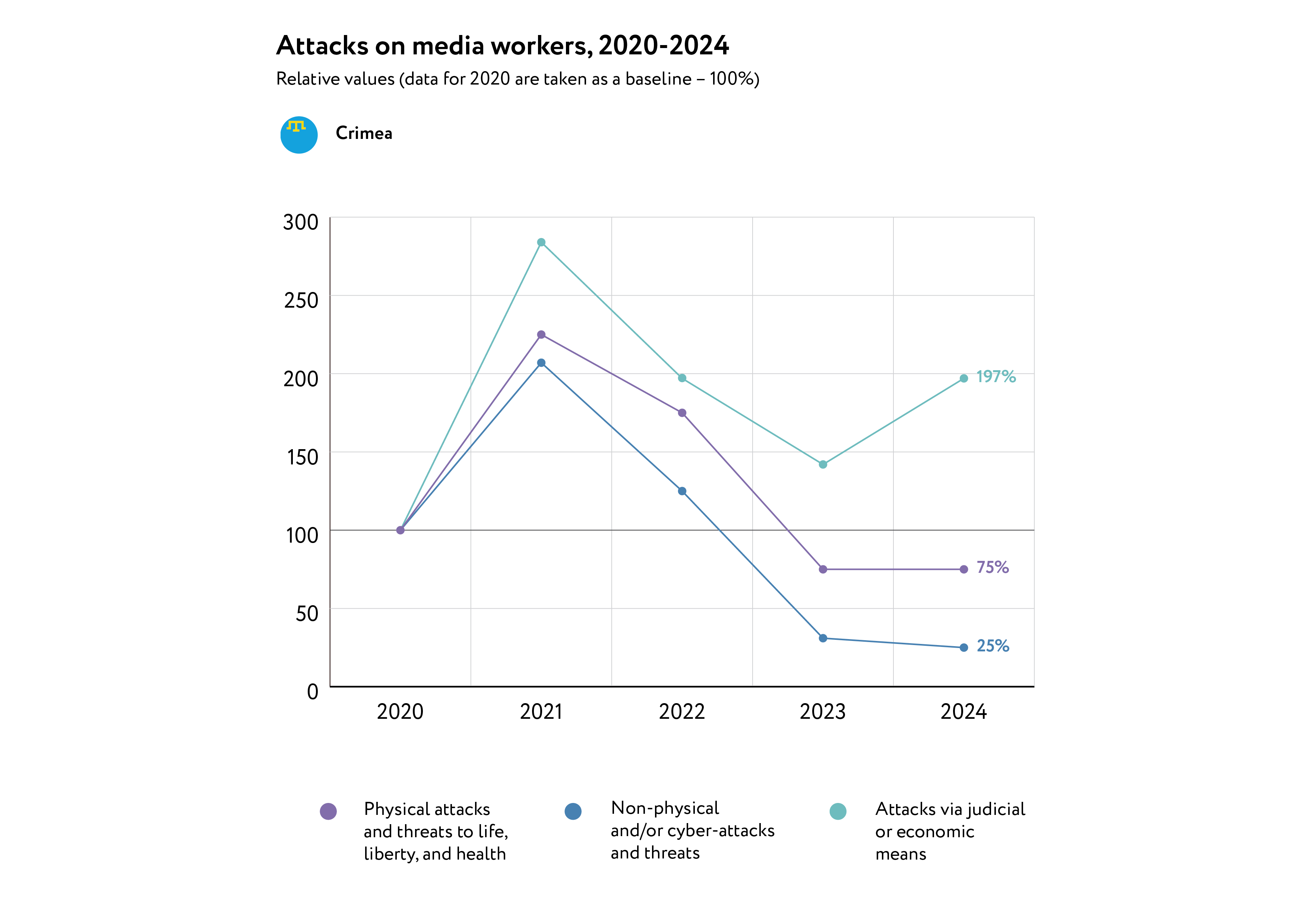

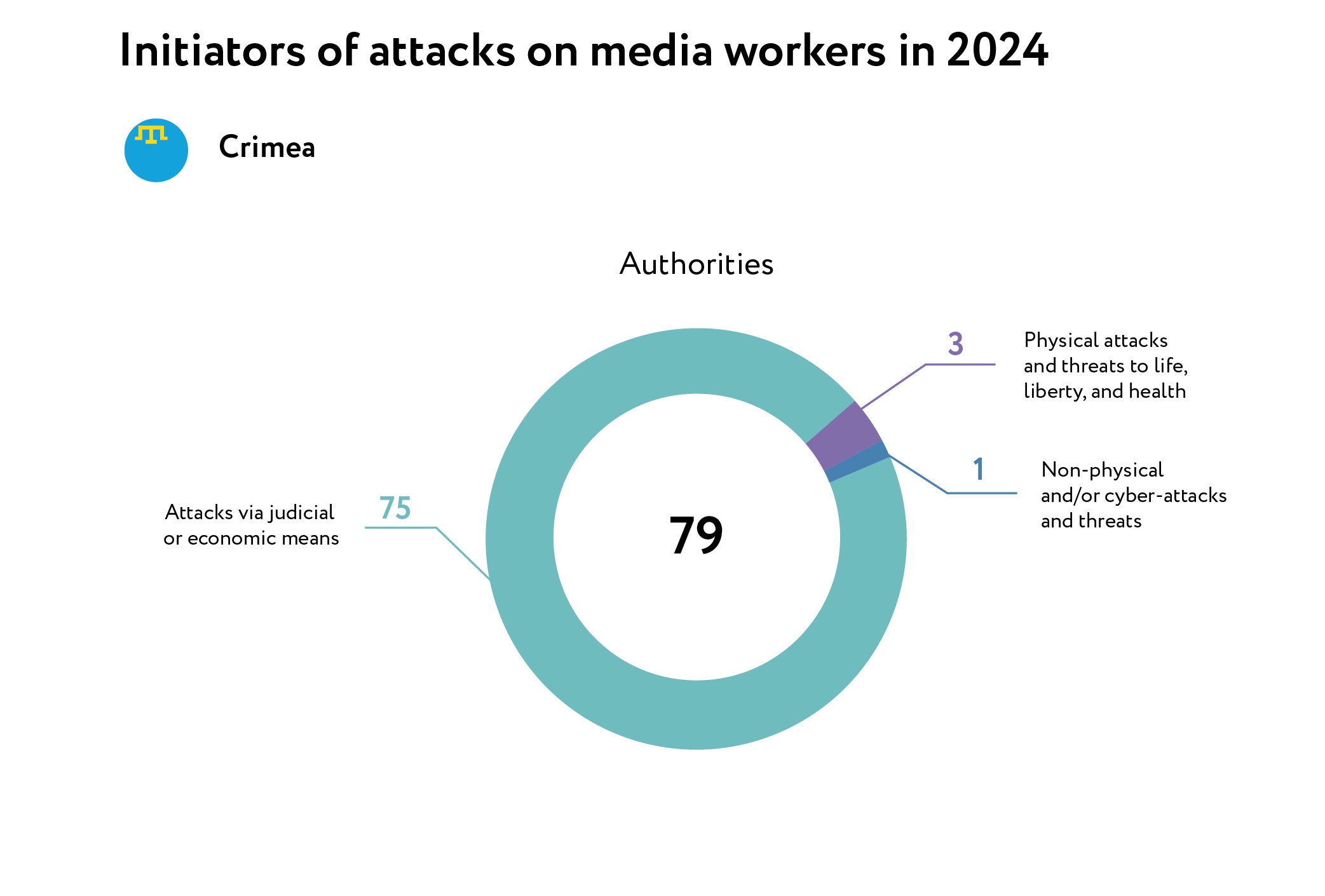

In Russian-occupied Crimea, 79 cases of attacks/threats against professional media workers and citizen journalists, editorial offices of traditional and online media outlets, Telegram channels and online activists, were identified and analysed in the course of the research for 2024.

Data for the study were collected using content analysis from open sources, which were additionally verified, as well as from the ZMINA Human Rights Centre’s own fieldwork data. A list of the main open sources is provided in Annex 1.

- In 2024, the policy continued of total suppression of independent journalism, initiated by the Russian Federation after the occupation of the peninsula in 2014. This has led to a decline in the activity of the remaining independent journalists and the cessation of many informational initiatives in Crimea. A total of 79 attacks were recorded. The number of attacks has slightly decreased compared to 2022-2023 when in total 164 incidents were documented.

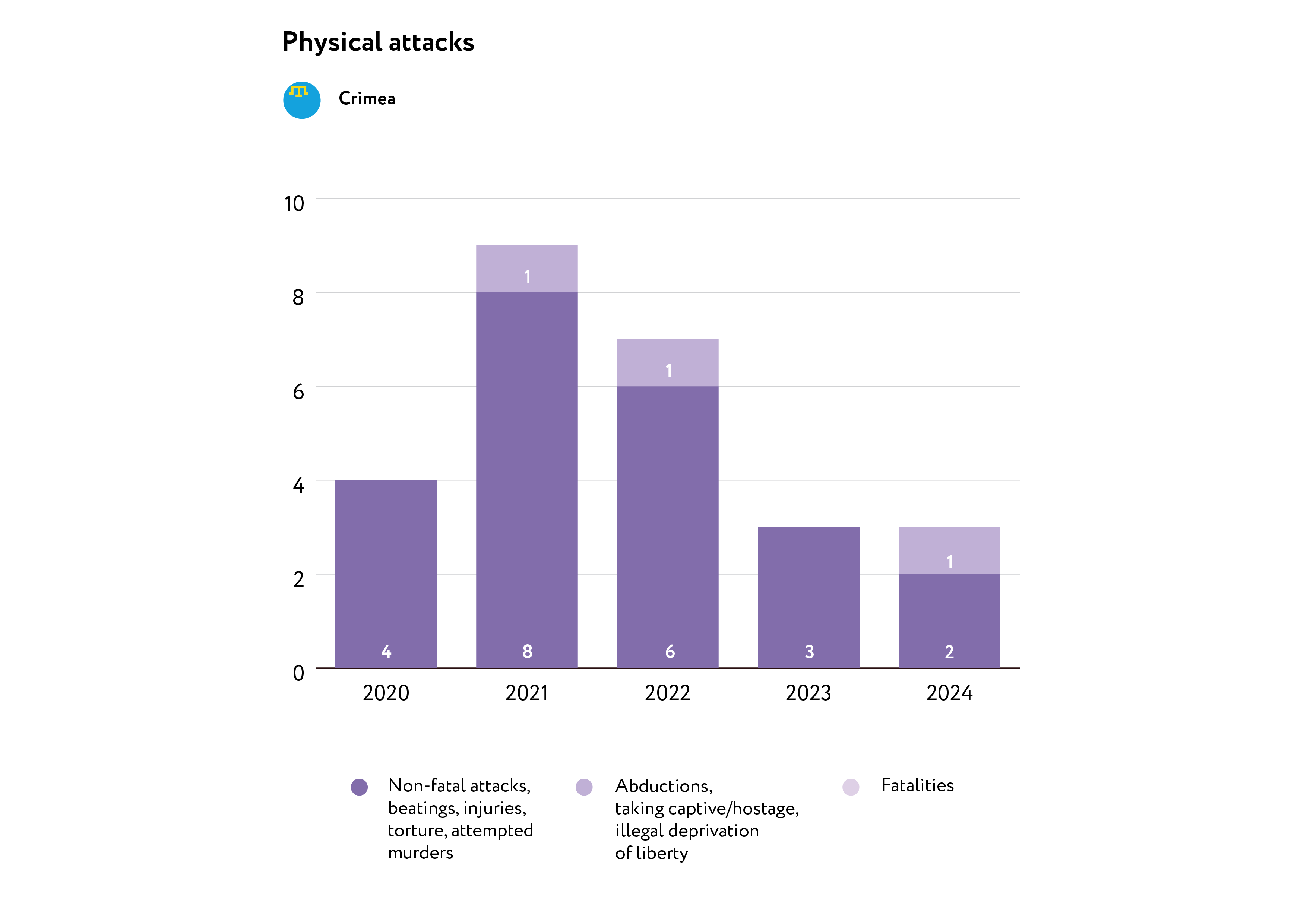

- In 2024, two cases of physical attacks and threats to the life, freedom and health of media workers were recorded, including the use of punitive psychiatry and abduction/unlawful deprivation of liberty.

- The primary source of threats against media workers remains government representatives.

- The main type of attacks against media workers, as well as bloggers and online activists in Crimea, is the use of legal and/or economic mechanisms, such as searches, detentions, court cases, fines for alleged administrative offences, and criminal prosecutions of journalists.

- This year, only one case of unlawful obstruction of journalistic activity through denial of access to information was recorded.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN CRIMEA

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine was accompanied by the introduction of new legislative restrictions on freedom of speech and expression, which impose administrative and criminal liability for criticising military actions, calling for peace, and supporting sanctions against the Russian economy. In Crimea, the implementation of these restrictions has been accompanied by a significant increase in extrajudicial pressure, threats, physical violence, and the fabrication of evidence for more serious crimes or offences.

In the World Press Freedom Index 2024 published by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Crimea was not studied as a separate region, but it was noted that Putin’s war against Ukraine has had a “significant impact on the media ecosystem and journalist safety”. The annual Freedom House report, Freedom in the World – 2024 rated Crimea at 2 out of 100, categorising it as a “not free” region. The political rights indicators fell into negative values (-2), making the situation in Crimea worse than in North Korea. In the 2023 report, the overall score was slightly higher at 4 out of 100.

With the onset of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the number of Ukrainian media resources blocked by Internet providers in Crimea has significantly increased. Throughout 2024, access to Ukrainian websites from Crimea remained almost completely blocked. Social networks such as Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube are also restricted, and most VPN applications used to bypass censorship either work unreliably or do not work at all. Moreover, media controlled by the occupying authorities have spread information about possible penalties for using VPN services.

Legislative Regulation of Media and Journalistic Activities

At the Crimean legislative level, there are no specific regulatory legal acts governing media activities. The legal framework of the Russian Federation applies in the temporarily occupied territory of Crimea.

- In 2024, the list of actions classified as administrative offences under Article 13.15 of the Russian Code of Administrative Offences (CoAP RF), Abuse of Freedom of Information was expanded once again. Specifically, on 8 August, a new Clause 12 was added, which includes the following as abuses of freedom of information: The dissemination of information via information and telecommunication networks, including the Internet, that insults human dignity and public morality, expresses clear disrespect for society, contains depictions of actions with signs of illegality, including violence, and is distributed out of hooliganism, selfish motives, or other base intentions. At the same time, some of the wording in this clause (such as public morality and other base intentions) is not defined at the legislative level as a legal term, allowing for a broad interpretation of this provision.

- In January 2024, the Russian Ministry of Justice amended Article 6 of the Federal Law “On the Perpetuation of the Victory of the Soviet People in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945”, incorporating a ban on the publication or display of certain Ukrainian symbols and insignia. Any publication or demonstration of such symbols is now considered an administrative offence under Article 20.3 of the Russian Code of Administrative Offences (“Propaganda or Public Display of Nazi Symbols or Symbols Similar to Nazi Symbols”). Among the symbols affected by this regulation is the Ukrainian national emblem (a golden trident, the central element of which resembles a double-edged sword), as well as the phrases “Glory to Ukraine” and “Glory to the Heroes”. These new provisions may significantly restrict the ability of journalists to select audio, photo, and video materials when preparing reports related to Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine.

- Article 20.3.3 of the Russian Code of Administrative Offences, introduced on 4 March 2022, continues to impose severe limitations on journalistic activities. This article prohibits “public actions aimed at discrediting the use of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation in protecting the interests of the Russian Federation and its citizens, maintaining international peace and security, or fulfilling state authorities’ duties in these areas”. This law continues to have a serious impact on the ability to freely report on Russia’s military aggression, including presenting alternative or neutral viewpoints.

A separate issue is an internal directive (a joint order from the Judicial Department of the Republic of Crimea and the Federal Bailiff Service of Crimea, issued on 25 February 2022). Citing this order, most judicial authorities prohibit access to court buildings for non-participants in legal proceedings, allegedly “to enhance anti-terrorist security measures, prevent unlawful actions within court premises, and increase the safety of judges”.

These measures continue to significantly restrict the ability of journalists to carry out their professional duties when covering judicial proceedings.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

In 2024, 79 attacks were recorded, of which 75 involved judicial and/or economic means, three were physical attacks, and one was non-physical. All recorded attacks were carried out by government representatives.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

In 2024, three physical attacks and threats to the life, freedom and health of media workers were recorded. The number of cases of physical violence remained at the same level as in the previous year. However, compared to earlier periods, there was a decline, which is attributed to a general decrease in journalistic activity in the region.

- On 2 May, it became known that Aziz Azizov, a citizen journalist from Crimean Solidarity who was accused of terrorist activities, was sent to a psychiatric hospital for evaluation under coercive conditions despite the absence of medical indications. Other political prisoners stated that, during this period, healthy individuals were held together with psychiatric patients.

- On 21 November in Simferopol, between 11:00 and 15:00, three plainclothes individuals forced Edie Muslimova, the editor of a Crimean Tatar children’s magazine, into a minivan. Her mobile phones were turned off until 23 November. Later, she revealed that she had been taken to the FSB and interrogated without legal representation. She was subjected to continuous questioning for 35 hours without sleep, which amounts to psychological torture. She was eventually released.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

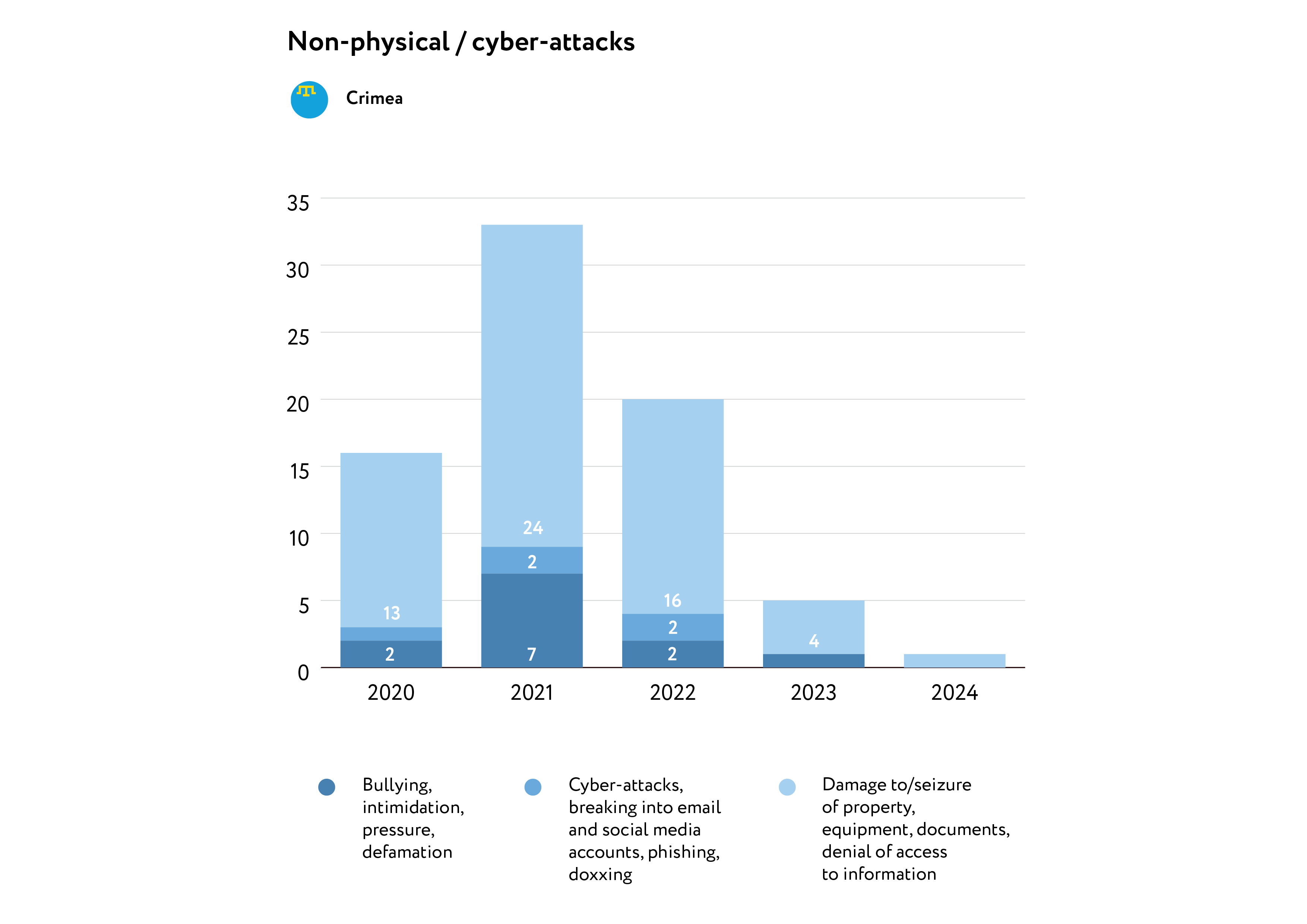

In 2024, only one non-physical attack was recorded, compared to 17 over the previous two years. This is explained by the almost complete absence of journalistic activity due to high risks (such as the possibility of being suspected of espionage) and the prolonged enforcement of various restrictions related to the military aggression against Ukraine.

On 15 April 2024, in Belogorsk, during the appeal hearing in the case of human rights defender Abdureshit Dzhepparov, court bailiffs did not allow observers into the courtroom, including a citizen journalist from Crimean Process.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

In 2024, attacks using legal mechanisms remain the predominant method of pressure. The most widespread form of persecution continues to be complex attacks structured in the following sequence: detention – initiation of an administrative/criminal case – trial – administrative detention, criminal arrest, or a fine.

In one case, the detention of a journalist was followed by the issuance of a summons to the military commissariat:

- On 29 February, after the detention of religious figures in Staryi Krym, journalist Ali Seytablaev from Crimean Solidarity was waiting outside the courthouse to cover the case. He was detained by an officer named Shambazov from the Centre for Combating Extremism and taken to a local police station. Later, he was released, but he was issued two summonses to the military registration and enlistment office.

Among the main methods of pressure are the initiation of criminal and administrative cases under various articles (23), searches (9), and fines for administrative offences (9). The majority of administrative prosecutions are related to the publication of materials mentioning organisations included in the register of foreign agents or the register of organisations whose activities are prohibited.

- On 22 February, Lutfiye Zudiyeva, a journalist from Crimean Solidarity, was charged with two administrative offences under Article 13.15 of the Russian Code of Administrative Offences (“Abuse of the Freedom of Information”). One charge was for failing to mark Radio Liberty as a foreign agent in a social media post, and the other was for mentioning “Hizb ut-Tahrir” without stating that it is banned in Russia. On 17 April, a court in Simferopol found her guilty and fined her 2,000 Russian Rubles ($22).

- On 23 May, a judge of the Leninsky District Court of Sevastopol found Meduza journalist Anastasia Zhvik guilty of an administrative offence under the article “Participation in the activities of a foreign or international non-governmental organisation that has been declared undesirable”. The court fined her 10,000 Russian Rubles ($109).

- On 12 December, in Simferopol, Judge Maria Domnikova of the Zheleznodorozhny District Court found Qirim editor Bekir Mamutov guilty of violating Article 13.15 of the Russian Administrative Offences Code (“Abuse of freedom of mass information”) for mentioning organisations recognised as foreign agents in an article without indicating their status. The fine was 4,000 Russian Rubles ($44).

Additionally, administrative prosecutions included cases of “discrediting the Russian army” and the dissemination of “false information” – specifically, citing a report by the UN Secretary-General.

- On 17 May in Simferopol, following a search and seizure of equipment, officers from the Centre for Combating Extremism detained Qirim editor Bekir Mamutov and took him to the centre. His lawyer was not permitted to enter the premises. Simultaneously, searches were conducted at the home of Seyran Ibrahimov (the publication’s founder) and at the newspaper’s editorial office. Mamutov and Ibrahimov were charged with administrative offences for two publications – one allegedly involving “discrediting of the Russian army”, and the other (a translated section of the UN Secretary-General’s report on human rights in Crimea) – “disseminating false information of public significance”. The Kyiv District Court of Simferopol found Mamutov guilty and fined him 130,000 Russian Rubles ($1,400) for “abuse of media freedom” and 100,000 Russian Rubles ($1,100) for “discrediting the Russian army.”

- On 7 June, the Kyiv District Court of Simferopol fined the Crimean Tatar newspaper Qırım 300,000 Russian Rubles ($3,300) under an administrative charge of discrediting the Russian army. The protocol against the newspaper had been issued in mid-May. In addition to the discreditation charge, the newspaper was also accused of disseminating “fake news” on matters of public significance.

In 2024, the trend of accusing citizen journalists of terrorism continued, leading to the arrest of two more journalists, and the practice of defamation charges was revived:

- On 5 March, several searches were conducted in Bakhchysarai, including at the homes of two citizen journalists from Crimean Solidarity, Aziz Azizov and Rustem Osmanov. On the same day, the Kyiv District Court of Simferopol, in a closed session, imposed a preventive measure in the form of detention for two months. They were charged under Article 205.5 of the Russian Criminal Code (“Organisation of the activities of a terrorist organisation and participation in such activities”) for alleged involvement with Hizb ut-Tahrir. The court subsequently extended their detention several times.

- On 19 June, Judge Oksana Karchevskaya of the Kyiv District Court of Simferopol reviewed a protocol and found journalist Anna Gajala guilty of failing to comply with a lawful police order after she refused to accompany officers to a search at her registered address without a warrant or lawyer. She was sentenced to 13 days of administrative arrest. On 11 July, the Kyiv District Court of Simferopol imposed a preventive measure in the form of detention for one month and nine days on charges under Article 128.1 of the Russian Criminal Code (“Defamation”). The court subsequently extended her detention several times. In February 2025, media reports indicated that the court had changed her preventive measure and released her under travel restrictions.

Other recorded incidents in 2024 included:

- On 26 January at around 6 a.m. in Simferopol, a search was conducted at the home of Crimean Tatar journalist Zera Bekirova (former editor of the Yanı Dünya newspaper) and editor of Nenkedzhan magazine. All of her electronic equipment was confiscated during the search. Afterwards, Bekirova and her daughter were taken to the FSB office for interrogation, which lasted approximately six to seven hours.

ANNEX 1: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (CRIMEA)

- The Crimean Human Rights Group – an initiative made up of representatives of human rights organisations, whose goal is to promote the observance and protection of human rights in Crimea.

- The Crimean Solidarity Public Movement – an informal human rights organisation created to protect victims of political repression.

- Crimea.Realities – a Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty service; an online media outlet that covers political persecution in Crimea in detail.

- Crimean Process – an association of experts and volunteers who assess the peculiarities of legal proceedings in political cases in Crimea.

- The ZMINA Human Rights Centre – a Ukrainian non-governmental organisation that concentrates on freedom of speech protection, and supports human rights and civil rights activists in Ukraine, including occupied Crimea.

- Social media platforms Facebook and VKontakte

- Free access Russian-language media on the Internet.

- Official websites of judicial bodies created by the Russian Federation in Crimea.