Zaborona published the second part of the investigation into the murder of journalist Pavel Sheremet. The investigation is supported by JFJ Investigative Grant Programme.

In the first part of the investigation, Zaborona said that Maksym Zotov, who is closely associated with the former tax minister Olexander Klymenko, may be involved in the murder of Sheremet. He was also the informal owner of Radio Vesti, where Sheremet worked.

However, we don’t exclude that Zotov was deliberately slandered. There are serious reasons for this.

A month before the murder of Sheremet, control over the criminal case of Klymenko was acquired by the military prosecutor’s office, headed by Anatoly Matios. Sheremet considered him his friend.

In 2019, Donetsk businessman Vladyslav Dreger said that he was involved in the scheme to fabricate the Klymenko case. He said that it was developed by Matios, his deputy, SBU officers and a people’s deputy from the Popular Front party.

Dreger had a business conflict with the Zotov family.

In the first part, we talked about the fact that the investigation into the murder of journalist Pavel Sheremet had not considered an important lead – the possible participation of the close circle of the the fugitive Minister of Revenue and Duties Oleksandr Klymenko. Maryna Matsyuk, the internally displaced woman from Donetsk, told investigators that her former neighbor Maksym Zotov – who, as Zaborona found out, was a business partner of the ex-minister – had told her about the organization of the murder.

However, the questionability of the situation as described by Matsyuk, her reluctance to provide any explanations, as well as the circumstances of her family’s life in 2016 came to make us think that this could possibly be slander. But who could have brought such a non-public and hitherto practically unknown figure as Maksym Zotov into the Sheremet case?

We decided to analyze the political context surrounding the murder of our colleague, and among many other important circumstances, we discovered the following: A key witness of the military prosecutor’s office for the Klymenko case in 2016-2017 had done business with the Zotov family. This witness claimed to have participated in the fabrication of the Klymenko case. Other cases in which he participated suggest the existence of an entire industry of “duty witnesses” created by high-ranking representatives of the Ukrainian law enforcement system.

Why is this important for the investigation of the Sheremet case? The connection between the witness in the Klymenko case and, most likely, the falsely accused person involved in the Sheremet case strengthens our belief that the murder of the journalist is inextricably linked with the criminal case of the fugitive minister.

The appearance of a figure associated with Klymenko in the Sheremet case could at least be used to put pressure on the ex-minister, who wanted to return to Ukraine, but as a result, never did. This could also be an attempt to divert the investigation from the real killers of the journalist. In this case, such a stuffing could shed light on who is behind the murder of Sheremet. It is all the more surprising that the investigation was not interested in the origin of the incredible story told by Maryna Matsyuk.

This material is limited to considering one of the versions, ignored by the investigation, but we continue to study other aspects of this confusing case. The facts discovered and compared at the moment make us think that the reason for the murder of Pavel Sheremet is highly likely at the intersection of the interests of political and oligarchic groups, which are represented by two people – Oleksandr Klymenko and Anatoly Matios.

A glass of whiskey

A month after meeting with Klymenko and a few days before his death, Sheremet met with Anatoly Matios. He called the military prosecutor and the major general of the SBU his friend. They met shortly before the interview that Pavel made with him for Ukrainska Pravda in February 2015. In the preamble, which the journalist wrote to that conversation, Sheremet calls Matios “a real Ukrainian patriot.”

Olena Prytula, the common-law wife of the journalist, said in an interview with Zaborona that she still cannot understand the nature of the friendship between Matios and Sheremet. According to her, the journalist and the prosecutor met once every two to three weeks, “he could slip out and go to him at any time.” However, the usefulness of such a friendship for Ukrainska Pravda is obvious – the military prosecutor was always available for comments on current topics and helped to clarify various information.

Prytula does not know anything about the nature of Sheremet’s last meeting with Matios, nor about most of the meetings between the journalist and the military prosecutor. As Matios himself said in an interview with Strana.ua in 2018, he helped to issue a pass to the journalist for access to the ATO zone. The need for someone at such a high level to issue a fairly standard pass could be explained by the journalist’s Russian citizenship, or perhaps by the fact that it was easier for Sheremet to do it through Matios than to go through standard bureaucratic procedure. Matios claims that they had bought a bottle of whiskey, which they agreed to drink upon Sheremet’s return. On the anniversary of the journalist’s death, Matios takes out that bottle and “drinks a glass,” he stated in that interview. According to him, Sheremet’s trip to Klymenko was also discussed during that last meeting.

The topic of Klymenko was not an idle one for Matios – a month and a half before this conversation, the military prosecutor gained control over the criminal case of the ex-minister and employer of the journalist. This was one of the results of the political crisis that erupted in Ukraine in 2016. We consider it important to recall these events, as they provide a key context for understanding what happened to Pavel Sheremet, as well as the triangle of relationships between Sheremet, Matios and Klymenko.

“To sow seeds of disorder and chaos”

At the beginning of 2016, the seat of Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk, whose Popular Front party was losing the rest of its support, began to swing – its rating was below 1% from 22% in the 2014 elections. The party controlled the post of head of the Security Council of Ukraine and two key power departments – the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Ministry of Justice – and had its own military council, which included Security Council head Oleksandr Turchynov, Andriy Parubiy, who became the speaker of the Rada in April 2016, Interior Minister Arsen Avakov, and several commanders of the volunteer battalions.

The idea of early elections hung in the air, which would have ended the careers of all the aforementioned political figures. Opinion polls showed that a new political force led by the sworn enemy of the Popular Front, Mikhail Saakashvili, as well as pro-Russian parties, would have an excellent chance at going for them. It was with this scenario in mind that Oleksandr Klymenko’s Successful Country party, mentioned in the first part of our investigation, was created.

The Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine was also under attack – Rada deputies, activists and even US Vice President Joe Biden demanded the resignation of Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin, whose subordinate was Matios.

The crisis peaked in April 2016, when Prime Minister Yatsenyuk and Prosecutor General Shokin were forced to resign. Meanwhile, members of the Popular Front organized noisy campaigns against businessmen connected with Russia and their media outlets. They even raised the idea of introducing martial law in the country. Oleksandr Turchynov, Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council, spoke about the possibility of such events developing the day before the death of Pavel Sheremet.

When it became known that the journalist had been killed, a prominent representative of the “militant” wing of the Popular Front, Andriy Levus, called the murder a terrorist attack by the Russian special services and called for an increased terrorist threat level to be announced, which, in his words, would allow prohibiting mass gatherings and carrying out “clear filtering measures”. Levus wrote that the Kremlin needed a “ritual sacrifice” and a “new Gongadze case” to “sow seeds of disorder and chaos in Ukraine.”

“Moral principles are negligible”

It is worth recalling that in 2016 the bombing of Pavel Sheremet’s car was not the first political assassination resembling a terrorist attack. The first victim was the lawyer Yuri Grabovsky. At the time of his death, Grabovsky appeared as an opponent of Matios’ military prosecutor’s office in the case of Russian special forces officers caught by the SBU – Aleksandrov and Erofeev. The same military prosecutor’s office, despite an obvious conflict of interest, also investigated his murder.

But first, let’s return to the circumstances in which Matios and his subordinates found themselves at the beginning of this fatal year for the journalist Sheremet and lawyer Grabovsky. In short, the ground was burning under the prosecutors’ feet.

By virtue of its specificity, the military prosecutor’s office was engaged in politically losing cases, such as the Ilovaisk tragedy and the crimes of military volunteers. By February 2016, Matios had made enemies with the Right Sector, the Tornado battalion and the commander of the Donbas battalion, Semen Semenchenko.

The situation was aggravated by the fact that in December 2015, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) opened a case on illegal enrichment against a key employee of Matios – a young and determined prosecutor of the ATO forces Konstantin Kulik, who would later receive scandalous notoriety, first in Ukraine, and then in the United States – due to participation in Donald Trump’s campaign to denigrate Joe Biden.

The ATO forces prosecutor’s office headed by Kulik was then only a few months old. Created by Matios together with the SBU, this emergency body would subsequently expand the territory of its activities far beyond the ATO zone and the military sphere in general. It would also come to play a key role in the story we are considering.

Unlike the rest of the cases, which were in the hands of the military prosecutor’s office, the case of the Russian special forces promised to bring political dividends – they were supposed to be exchanged for the political icon Nadiya Savchenko. But for this they first had to be sentenced. The military prosecutor’s office referred the case to court, but the process was delayed for several reasons, including the appeals filed by Aleksandrov’s lawyer Yuri Grabovsky.

In March, Grabovsky disappeared. Matios actively reported to the press about the search for the lawyer, saying that foreign special services were involved in the disappearance, but soon it became known that the lawyer had been killed. The case of his death was taken from the National Police by the military prosecutor’s office, allegedly for a “more effective” investigation. Soon, Matios released a video in which Grabovsky, before his death, apparently under pressure, declared that he had “realized his mistake” and refused to protect the Russians. In early April, the Russian GRUs were convicted, and on May 25th they were exchanged for Savchenko.

Despite the video made before Grabovsky’s death, clearly indicating that it had resulted from an act of intimidation, Matios said in August that the lawyer had been killed during a robbery. Immediately after the election of President Zelensky, one of the men convicted in the case, businessman Artyom Yakovenko, publicly accused Matios and the SBU of organizing this crime, but his statement did not have any visible legal consequences.

Nevertheless, the release of Nadezhda Savchenko was positive news, which the Ukrainian leadership sorely lacked in that crisis year.

Five days after Savchenko’s return, military prosecutor Matios was rewarded. The newly appointed new Prosecutor General of Ukraine Yuriy Lutsenko transferred the politically winning cases against Yanukovych’s entourage to the military prosecutor’s office of Matios, taking them from the department of special investigations of the General Prosecutor’s Office (GPO) of Serhiy Gorbatyuk, which had been conducting them for the previous two years. So, in the hands of Matios was the case of Pavel Sheremet’s employer and the long-standing target of the military prosecutor – the fugitive minister Klymenko.

As soon as the cases of Yanukovych’s entourage were transferred to Matios, he instantly created an investigation team headed by the same ATO prosecutor Konstantin Kulik. The investigators included in the group, according to Matios, had been previously called up for military service and signed a statement about being sent to the ATO zone. So the absolutely civil, Kyiv-based Klymenko case unexpectedly ended up at the front and in the hands of the prosecutor’s office, which, in theory, was only supposed to deal with war crimes.

The “honeymoon” of the two military prosecutors did not last long. Already in July 2017, Matios would characterize Kulik as a competent professional, whose “moral principles are negligible.” However, during 2016, when Sheremet was assassinated, both prosecutors acted closely together. As for Matios’ own moral principles, these were highlighted by President Zelensky when in 2019 he threatened to fire the new head of the SBU Ivan Bakanov if it turned out that he was working with the former military prosecutor.

But in a short period of close cooperation between Matios and Kulik, many important events happened that relate to our story.

“I don’t want to go into conspiracy theories”

The leadership of the military prosecutor’s office spent the summer of 2016 in a hard struggle and desperate maneuvering.

Two weeks later, after Matios had been given the cases against Yanukovych’s entourage, Matios submitted his name as consideration in the search for the position of head of the State Bureau of Investigation (SBI), which was being created in Ukraine, the Ukrainian counterpart of the FBI. In his own words, the result of the search was determined by the agreement of the factions of the Petro Poroshenko Bloc and the Popular Front, and he hoped that politicians would find common ground in choosing him, thus ensuring his victory. The resonant cases of Yanukovych’s entourage, quickly brought to court, could serve as good help in this. One of Matios’s competitors was prosecutor Sergiy Gorbatyuk, from whom he took away the cases. The process of appointing the head of the SBI eventually dragged on for years, and neither one nor the other received this post.

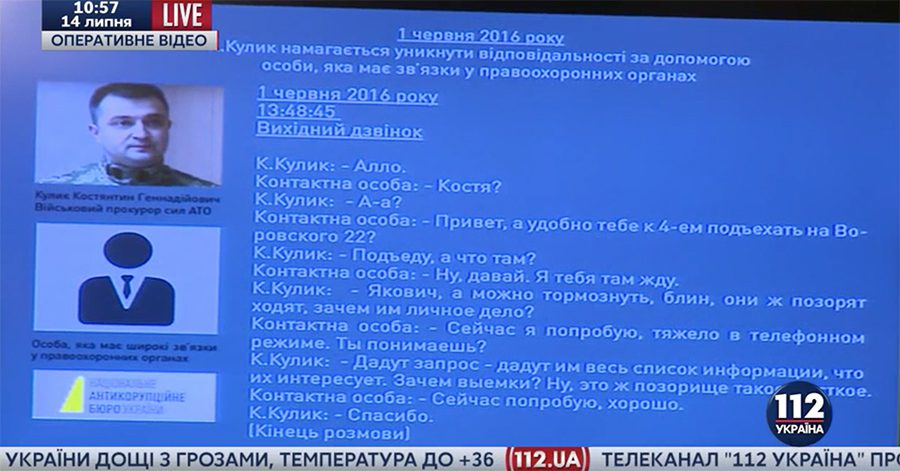

Meanwhile, the prosecution of the ATO forces prosecutor Kulik by NABU investigators reached its climax. On June 29, Prosecutor Kulik was presented with an official notification of suspicion of illegal enrichment, and his apartment was searched. He was accused of having accumulated property in excess of his total salary for five years during only a year and a half of service. On July 4th, the court removed Kulik from his post for two months, leaving him free as long as he did not leave the country.

On July 14th, a week before Sheremet’s death, NABU and SAP made public the wiretapping of the June telephone conversations of Prosecutor Kulik, from which it was possible to conclude that the transfer of the cases against Yanukovych’s circle, including Klymenko, to him could have been a way to save him from criminal prosecution. The People’s Deputy (Member of Parliament) and former journalist of “Ukrainian Pravda” Serhiy Leshchenko spoke about the same. Matios himself, meanwhile, was accused of intending to leak information on the Klymenko case.

In one of the following days, the meeting between Matios and Sheremet took place, which featured a bottle of whiskey that was left uncorked.

Pavel Sheremet was killed on July 20th. In five days, Matios would be the first to report the journalist’s Moscow meeting with the fugitive minister Klymenko. Subtly, he hinted that Klymenko might have been linked to journalist’s murder. “I don’t want to go into conspiracy theories, but at the last meeting with Pavel we discussed a lot of things – he was always an optimist, he was a bright person, but at that moment he described the situation of his stay in Moscow in dark colors,” he said in an interview on Channel 5.

“He visited the so-called Moscow City office center, where all our quasi-exiles are, whom we will definitely get and condemn. And one of these quasi-exiles was ex-minister of Minister of Revenue and Duties Klymenko. However, we were unable to convey the essence of that conversation,” Matios said.

Soon, events in the Klymenko-Sheremet-Matios triangle began to accelerate at an alarming speed.

On Saturday, August 6th, Mathios announced his intention to resign on September 1st.

On the following Monday, Marina Matsyuk came to the investigator of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, declaring that a man from Klymenko’s inner circle, Maksym Zotov, was involved in the death of Sheremet. On Tuesday August 9th, Prosecutor General Yuriy Lutsenko announced the arrest of the former Deputy Klymenko and the head of the tax police, Colonel-General Andriy Golovach. And on Saturday, August 13th, Matios reported on the disclosure of the case of the lawyer Grabovsky. The topic of resignation disappeared from the agenda.

Helicopter show

In September, Matios suggested that Golovach make a deal with the investigation, and it took place: he paid UAH 130 million to the treasury instead of UAH 3 billion, which, according to the prosecutor’s office, he had withdrawn from the budget through compensation for illegal VAT.

The culmination of the investigation was a large-scale special operation which occurred in May 2017, when 24 regional tax officers from the Klymenko era were arrested and taken to Kyiv by helicopter. At Zhulyany airport, they were met personally by Matios and Interior Minister Arsen Avakov, surrounded by dozens of television cameras. They solemnly called it the “second wave” of the investigation into the case of the fugitive minister.

Two months later, another operation took place, more like a show. On July 14th, 2017, armored vehicles and hundreds of special forces appeared in the center of Kyiv. They broke into the Vesti holding newsroom, where Sheremet worked until his death. Vesti staff did not resist. The operation was carried out on the basis of Matios’ decision to seize property associated with Klymenko. However, Klymenko, in unison with his common-law wife Semchenko, rejected the media holding’s connection with the “fugitive oligarch.”

The hands-on part of the operation, according to Matios, was carried out by Avakov’s people – the Rapid Operational Response Unit (KORD) and the defense department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The property associated with Klymenko was transferred to the Agency for the Search and Management of Assets (ARMA). These were the subordinates of Pavel Petrenko, the Minister of Justice, who, like Avakov, represented the Popular Front party.

The same Petrenko led the reform of the Penitentiary System of Ukraine, on which the fate of Mykola Matsyuk depended, whose wife told about the involvement of a representative of the Klymenko clan in the murder of Pavel Sheremet. By the time the operation in “Gulliver” was carried out, they had already moved to Kyiv, and Mykola Matsyuk had begun a successful career in the new national penitentiary structure created by Petrenko (we wrote more about this in the first part of the investigation).

The PR effect of the Klymenko case turned out to be much stronger than the legal consequences. A year after the “helicopter show”, all the arrested tax officials went free. Prosecutor Gorbatyuk, dismissed from the case, claims that, in fact, the case, which was almost ready for submission to the court, was compromised. First, the number of suspects that his group planned to prosecute has dropped sharply. Secondly, the court, according to Gorbatyuk, “would study for forty years” two thousand volumes of the case.

“Does the military prosecutor’s office have little to do?” GPO investigator Andriy Radionov, who directly led the Klymenko case under Gorbatyuk, was indignant. “The destruction of the armed forces under Yanukovych, corruption in the Ukroboronprom, colossal property crimes. There is also a war in the country, a lot of war crimes, Debaltsevo, Ilovaisk and so on. There is a lot of work to be done. Why take cases from other departments?”

Radionov claims that his investigators had built from scratch a case on the Klymenko group’s seizure of state budget funds totaling 3.2 billion hryvnias using a scheme to recover VAT through fictitious companies. None of the oligarchs received such amounts in Ukraine, says Radionov. “3.2 billion is a 1% drop in the state budget. This is a third of spending on the army, half of spending on education or medicine.”

Both prosecutors, in a conversation with Zaborona, suggested that there could be a corruption component in the deliberately botched case. It is noteworthy that two months before the “helicopter show” Matios succeeded in classifying the property declarations of 72 military prosecutors. They were only declassified after his retirement in 2019.

Звертає на себе увагу і той факт, що за два місяці до «вертолітного шоу» Матіос домігся засекречування декларацій про майно 72 військових прокурорів. Вони були розсекречені лише після того, як він пішов у відставку в 2019 році.

Few people at that moment understood what role in all these events was played by a not-too-famous and only recently released from prison Donetsk businessman and politician.

Confiscation scheme

In September 2019, a video appeared on social media – a monologue of a tired man with disheveled hair sitting in a kitchen, wearing glasses and a stretched T-shirt. This was Vladislav Dreger, the businessman and deputy of the Donetsk Regional Council who had been evacuated to Kyiv. At the beginning of the monologue, he names the recording date – July 1st, 2017, as well as the time – 23:45. If you believe this dating, then the case takes place a year after the death of Sheremet and two weeks before the storming of the offices associated with Klymenko in the Gulliver Business Center in Kyiv. There is no doubt that it is Dreger who is depicted in the video, but our attempts to contact him were unsuccessful – he did not answer phone calls and questions sent via SMS. Matios, who retired in September 2019, also declined to comment.

In his monotonous speech, Dreger claims that he was part of Matios’s scheme to fabricate the case of Oleksandr Klymenko with the aim of confiscating his Ukrainian assets, specifically media assets. Primarily among the latter was the Vesti media holding, where Sheremet worked.

The creators of the scheme, according to Dreger, justified their actions by the need to “protect the economic and informational interests of Ukraine.” In addition to Matios, Dreger claims, Deputy Military Prosecutor Dmytro Borzykh, as well as a Rada deputy from the Popular Front, ex-Deputy Head of the SBU Andriy Levus and SBU officer Bohdan Chobitok, took part in the development of the scheme. In addition, according to him, the meetings were attended by investigators who were directly involved in the cases of Klymenko and his arrested deputy Golovach.

Dreger’s value to the prosecutor’s office was that he had interacted with Oleksandr Klymenko and his late brother Anton in business long before Maidan. However, in 2011, he ended up in prison on charges of hostile takeover of one of the Donetsk enterprises, and the tax police, subordinate to Oleksandr Klymenko, opened a case against him. Dreger was released immediately after the victory of the Maidan Revolution and, according to his own statement, considered Klymenko to be his debtor.

Other participants in the meeting, named by Dreger, are no less colorful.

A prominent representative of the “militant wing” of the Popular Front and an ardent supporter of revolutionary expropriations, Andriy Levus, was associated for many years with the former head of the SBU Valentin Nalyvaichenko. After the victory of the revolution, he became deputy head of the SBU for six months, responsible for work with the volunteer battalions that were being created at that time. According to his own Facebook posts, Levus also led the Donbas guerrillas who carried out acts of sabotage against the Russian military and local separatists, including bombings.

In 2016, he was not only the People’s Deputy from the Popular Front, but also the leader of the nationalist movement “Free People”, which organized actions all year against political organizations and the media, one way or another connected with Russia. In May and June 2016, members of the movement actively disrupted regional events of the Klymenko Party Successful Country. Currently, Levus has the status of assistant to the deputy and former speaker of the Rada Andriy Parubiy.

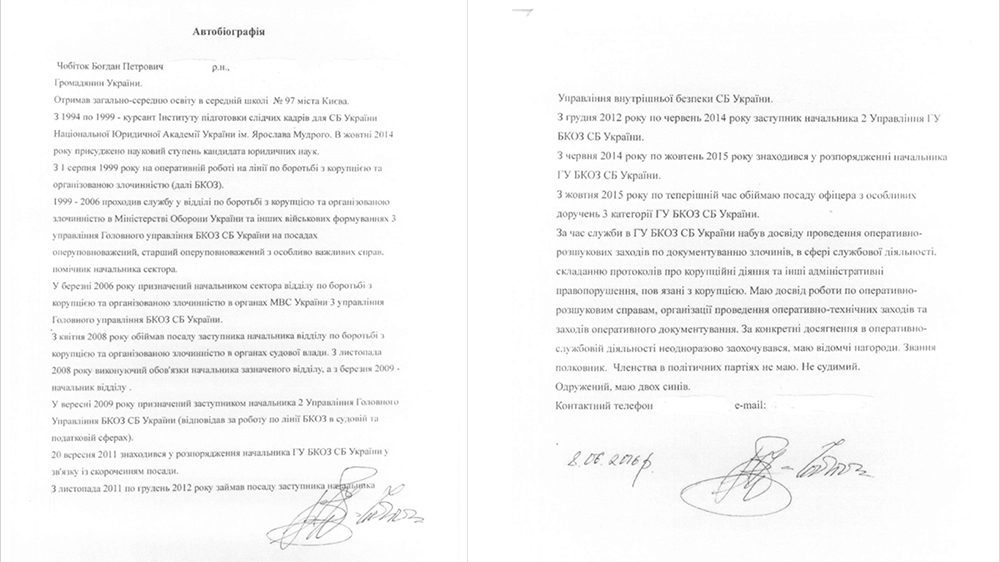

Bohdan Chobitok is an SBU operative who did not hold significant posts and was absolutely not public until June 2016, when he – like Matios – announced his candidacy for the post of head of the State Bureau of Investigation. Although he was not chosen, he received, unlike Matios, a position in the new structure – in 2018 he became the head of the Bureau’s Internal Control Department.

In his video monologue, Dreger claims that in August and September 2016, he participated in several secret meetings with the aforementioned people. The meetings, he said, took place in the office of Matios himself in the building of the prosecutor’s office, where he was secretly brought in an official car without first registering at the checkpoint.

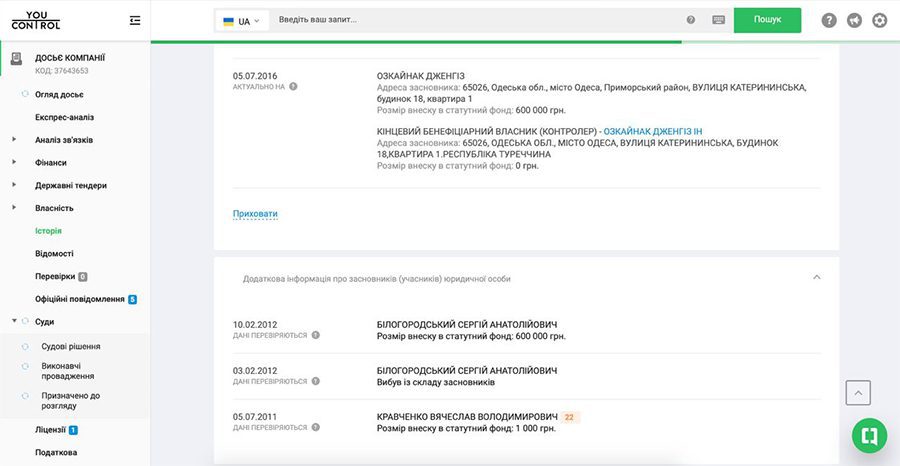

According to Dreger, this was the scheme: he had allegedly made contact with an unknown foreign citizen, whose name was listed with the Cypriot offshore companies that controlled the alleged assets of Klymenko, and agreed to buy them out. In exchange, Matios promised Dreger to help the Turkish citizen Ozkainak Jingiz in a conflict with a former partner, and later the sworn enemy of Dreger himself, businessman Sergiy Belgorodsky. The Turkish citizen, in turn, would finance the purchase of assets associated with Klymenko.

From the Turkish citizen, the assets associated with Klymenko were to be transferred to Dreger himself, who would then declare himself a member of Klymenko’s “criminal group” and file a confession, transferring Klymenko’s capital to the state as part of a deal with the investigation. “To give maximum credibility” to his relationship with Klymenko and on Matios’ “personal assignment,” Dreger allegedly traveled to Moscow more than six times from November 2016 to March 2017 in order to secure a meeting with the fugitive minister and secretly record the conversation to pass it on to prosecutors. … However, attempts to reach Klymenko were not crowned with success.

In the spring and summer of 2017, Dreger claims, he came under intense pressure from Matios, which forced him to record this video as a safety net. Dreger’s video was posted online on September 19th, 2019, two weeks after President Zelensky sacked Matios. In October, the new military prosecutor Viktor Chumak said that a pre-investigation check was being carried out on the facts presented by Dreger.

It is important to understand that Dreger has repeatedly acted as a witness in various high-profile cases. For example, he testified against the former Colonel of the Armed Forces of Ukraine Ivan Bezyazykov, who was accused of treason, as well as in the case of Viktor Tatkov, ex-head of the Supreme Economic Court of Ukraine. In addition, according to Zaborona’s sources, he was a secret witness in the Klymenko tax case (“helicopter case”). At the same time, he was often the only witness for the prosecution, positioning himself as an accomplice in the crime – and, despite the continued recidivism, remained free.

A completely similar scheme, but with a different witness, is described by slidstvo.info in its investigation of the second high-profile case concerning Yanukovych’s entourage, which was also conducted by the military prosecutor’s office and specifically the prosecutor of the ATO forces Konstantin Kulik. The key witness turned out to be a former prosecutor and a fellow classmate of Kulik’s at the Yaroslav Mudryi Kharkiv National University. It is interesting that Bohdan Chobitok and Vladislav Dreger also studied there and during the same years.

Anatoly Matios ignored the questions of Zaborona correspondent. Andrei Levus refused to answer our questions, but his colleague Sergei Vysotsky, in a conversation with Zaborona journalist, said that “there was no fabrication of the Klymenko case”. Zaborona failed to contact Bohdan Chobitok.

Our source who worked in the General Prosecutor’s Office of Ukraine until mid 2019 confirmed to Zaborona correspondent that Dreger had testified in the Klymenko case, as well as in the case of Yanukovych orbit, to the prosecutor of the GPU Department of Special Investigations since March 2016.

Oleksandr Klymenko criminal case timeline

February 2014

Oleksnadr Klymenko flees to Russia

29.04.2014

Klymenko notified that he is suspected of exceeding authority

03.09.2015

Klymenko announces that he intends to return to Ukraine, launches Successful Ukraine party project

30.05.2016

Ukraine’s new Prosecutor-General Yuri Lutsenko announces that Klymenko case is being transferred to the military prosecutor’s office led by Anatoly Matios.

10.06.2016

Klymenko meets with Pavel Sheremet in Moscow

20.07.2016

Pavel Sheremet’s assassination

08.08.2016

Marina Matsyuk testifies about Maksim Zotov’s alleged link to Sheremet’s murder

09.08.2016

Klymenko’s former deputy Andriy Golovach gets arrested. In September, Matios would offer him a deal with the investigation.

24.05.2017

“Helicopter show”: two dozens of arrested regional tax officials are being transported to Zhulyany airport in Kyiv, where they are being greeted by Matios and interior minister Arsen Avakov.

14.07.2017

Security agents raid Gulliver business centre, search premises of Vesti Ukraine media holding. Matios arrests Klymenko’s assets.

Жовтень 2017

Arrested Klymenko’s assets are being transferred to ARMA state agency.

22.11.2017

Military prosecutor’s office charges Klymenko with treason.

14.03.2018

Tax officials arrested in “helicopter show” officially become suspects in the case.

30.07.2018

Prosecutor-General’s Office concedes that all the arrested tax officials have been released because their detention term has expired

19.08.2019

Klymenko arrested in abstentia by Kyiv’s Pechersk court

02.09.2019

Matios resigns

19.05.2020

The chamber of appeals of the Supreme Anti-Corruption Court cancels the court ruling to arrest Klymenko.

“Unreliable witness”

One of the cases in which Dreger acted as a witness may serve as a clue to the reason for the appearance of the name of the unknown Maksym Zotov in the case of Pavel Sheremet. As Zaborona found out, Dreger had business run-ins and probably clashed with the Zotov-Epel family before he was sent to prison under the previous government.

This is a terrorist organization case against Sergei Belgorodsky, Dreger’s former business partner. Belogorodsky claims that Dreger had previously tried to tie his case to the Klymenko case. He was arrested on May 28th, 2016 – two days before Matios got his hands on the cases of Klymenko and other representatives of Yanukovych’s entourage.

A year later, Belogorodsky would declare that the arrest was carried out at the insistence of two people’s deputies – the former deputy head of the SBU, Andriy Levus, whom Dreger mentions in his video, as well as an ally from the “Free People” movement, Sergiy Vysotsky from Popular Front Party. In a conversation with Zaborona correspondent, Vysotsky said that he “did not do this”, but confirmed that he knew Dreger “from the time when he led the Strong Ukraine party in Donetsk”.

In an interview with Zaborona, Belgorodsky said that the deputies were well acquainted with Dreger and acted in his interests, and “Free People” picketed the court during his trial. Dreger himself acted as the main witness, accusing his former partner of financing terrorism in the LNR / DNR as well as the creation of the separatist group “Oplot” in Donetsk.

The Belgorodsky case fell apart in court and in 2017 he was released. At the same time, the court recognized Dreger as an “unreliable witness”. But while Belgorodsky was in prison, his assets were rewritten (this can be seen through YouControl) in the name of a Turkish citizen Ozkainak Jingiz – the very one whom Dreger mentions in his video.

During the trial over Belgorodsky, the name of another alleged developer of the scheme for the confiscation of Klymenko’s property – SBU officer Bohdan Chobitok – surfaced. Belgorodsky, in an interview with Zaborona, claims that he had been a friend of Dreger and even “helped him do business” while he was in the Kyiv pre-trial detention center. Until the fall of 2015, Chobitok worked at the disposal of the deputy head of the “K” department of the SBU for combating corruption, and even earlier – as the deputy head of its secondary department. This department, among other things, controlled the activities of the Ministry of Revenue and Duties, which Klymenko had headed before his escape. Incidentally, on the eve of Maidan, Anatoly Matios, who then worked in the Yanukovych administration, was – in his own words – the head of the working group which controlled the Ministry of Revenue and Duties.

Autosputnik

The history of relations between Dreger and Belgorodsky begins in the 2000s. Then they jointly privatized the Donetsk Regional Bus Station Enterprise (DOPAS), which included almost 50 bus stations in the region and several parking lots. According to Belogorodsky, Dreger tried to monopolize the intercity trucking and transportation business in the southern and eastern regions of Ukraine.

But in 2011 the situation changed. In the process of establishing control (the local media called it a raider seizure) over the Mykolaiv regional enterprise of bus stations, Dreger faced an obstacle that turned out to be insurmountable. Back at the time, Rada deputy Oleksandra Kuzhel stated that Oleksandr Yanukovych, the son of the former president, was party to the conflict. However, other Zaborona sources say that it was a conflict with the business partners of the Klymenko clan.

The fact is that one of the key buildings of the Mykolaiv complex belonged to the Avtosputnik company, which was under the control of Olga Epel and that same Maksym Zotov, whom Maryna Matsyuk would name as the organizer of the murder of Sheremet. That is, the complex of the Mykolaiv bus station was divided between Dreger and the Zotov-Epel family.

According to Belgorodsky’s lawyer Yulia Semenchuk, who conducted her own investigation, Dreger had “an open corporate conflict over a small premises at the Mykolaiv bus station, he opposed its owners”, that is, the Zotov-Epel family.

The struggle for influence at the Mykolayiv bus station became a stumbling block in relations between Dreger and Klymenko – because of this, the tax police opened a criminal case against him on a matter not related to the Donetsk Regional Bus Station Enterprise. So, Dreger ended up in the Lukyanivska Prison for three years, from where he could only be released after the victory of Maidan.

According to Belogorodsky, Dreger told him that at first he considered him – Belogorodsky – the mastermind behind his arrest. But then Dreger allegedly realized that Klymenko was the mastermind. We could not get Dreger’s comment, but if this is true, then he appears to be a modern reincarnation of Le Comte de Monte-Cristo, who took revenge on everyone who sent him to jail (Judge Tatkov also took part in his fate).

Thus, Vladislav Drager was not only one of the few people who knew about the existence of Maksym Zotov at all, but also had a personal motive to take revenge on Alexander Klymenko and his entourage

Moreover, if Belgorodsky and his lawyers are to be believed, he was already a key element in the criminal fabrication industry. To accuse them of the murder of Sheremet, and thus, at least, to thwart the return of Klymenko to Ukraine, would be a very significant revenge. However, the testimony of Matsyuk against Zotov did not have any – at least, open – influence on the course of the case.

What is Matsyuk talking about?

The version of Sheremet’s death as told by Maryna Matsyuk raises many questions. If there is any truth to the fantastic situation which she described – or at least to some of the facts stated – then why did the investigators of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, subordinate to such a prominent representative of the post-revolutionary Ukrainian elite as Arsen Avakov, who “personally controlled” the investigation, decide not to follow the “Russian trail” nor pursue representatives of the regime overthrown by Maidan in the case?

Unfortunately, Matsyuk herself did not consider it necessary to tell us more about the story of their acquaintance, and her husband, at Zaborona’s request to confirm or deny the situation described by Maryna Matsyuk, refused, adding that he “didn’t care” whether this fact would emerge in court.

Theoretically, Matsyuk could have slandered Zotov on her own initiative because of some lingering hostility or resentment. After the release of the first part of the investigation, Interior Ministry spokesman Artem Shevchenko told Zaborona that the investigators provided him with information that after Maryna Matsyuk’s visit in August 2016, they contacted her husband. The latter, according to the investigators, confirmed that Matsyuk was familiar with Zotov and said that she had a “long-standing conflict” with him. This statement, they say in the Interior Ministry, was a reason not to continue to investigate the data voiced by the woman: for example, they didn’t check whether Zotov was in Kyiv on the day of Sheremet’s murder and in Mariupol after. By the way, we didn’t find either the protocol of the interrogation of Mykola Matsyuk or the testing of Zotov among the case materials at the disposal of Zaborona.

Prosecutor of the GPO Andriy Radionov, at the request of Zaborona, commented on how the police should react to statements such as those made by Matsyuk. “Even such a suspicious version would have to be taken into consideration, if, of course, it is not entirely absurd, and [the applicant] is sane, she is also responsible if she gives deliberately false testimony”. In a telephone conversation Maryna Matsyuk gives the impression of a completely sane person.

One way or another, the Matsyuk family risked losing their livelihood in the summer of 2016 due to the dissolution of the penitentiary service, so it is unclear why Maryna Matsyuk took even more serious risks accusing rich and dangerous people, and even went to Kyiv from Mariupol to appear before investigators. Moreover, for a false testimony in a particularly grave crime, a criminal penalty is provided – imprisonment for up to 5 years. When asked whether an investigation was conducted into the slander against Matsyuk, Artem Shevchenko replied that “the investigators focused on finding real suspects, and not on punishing false testimony”.

If Matsyuk slandered Zotov at the request of or under pressure from officials on whom her husband’s career depended, then the question arises – who could have brought into the case the name of the absolutely non-public and little-known Maxim Zotov? And here attention is drawn to the fact that the key witness in the Klymenko case and the possible initiator of its fabrication – Vladislav Dreger – was not only familiar with the business of the Epel-Klymenko clan, but was also in conflict over property directly with the Zotov-Epel family, and since 2016, apparently, tried to bring their companies “Avtosputnik”, “Business-Invest” and other assets into the criminal persecution.

Also, of interest is Dreger’s connection with representatives of the Narodny Front’s “militant wing”, who waged an irreconcilable struggle against businesses and the media related to Russian interests. These people risked losing power and influence in Ukraine as a result of the political crisis in 2016 if early elections to the Rada took place.

However, no elections took place. The triumphant return of Oleksandr Klymenko to Ukraine did not take place either, and his party project was scrapped shortly after the murder of Sheremet. Radio Vesti stopped broadcasting in the main cities of Ukraine by March 2017, six months before the searches in Gulliver. Was this influenced by the threat of criminal prosecution in the Sheremet case? Or was Sheremet’s murder itself a “black mark” sent to the former minister?

It is important to note here that, by Ukrainian standards, gigantic huge amounts of money were at stake. According to Matios, Klymenko, together with his subordinates, withdrew $12 billion from the budget. Among these billions were the money of Zotov and Epel – people who, in our opinion, could be independent players in the conflict between the military prosecutor and the fugitive oligarch.

Another important point to consider is the alleged role in the history of former SBU employees, Matios, Levus and Chobitok, since it was the presence of the former SBU agent Igor Ustimenko near Sheremet’s house on the night of the murder that became the main discovery of the investigation of the journalists of the Slidstvo.info news agency – currently the most detailed and important investigative material on this topic. And the Deputy Interior Minister Anton Gerashchenko said in February 2020 that ten SBU officers are being checked for involvement in the murder of Sheremet.

In addition, if you believe in the authenticity of the published correspondence, the speaker of the Ministry of Internal Affairs Artem Shevchenko is convinced that the “counter-intel operators” (that is, the SBU) are guilty of the murder of Sheremet. “Let Yulia and Andriy [suspects Yulia Kuzmenko and Andriy Antonenko] honestly tell everyone who advised them and under what under what artifice to whack this goddamn Russian agent Sheremet and all. Although they did not know who and for what they were actually going to work”, he wrote. In a comment to Zaborona, Shevchenko said that “anyone can draw pictures online”. However, if the quote is authentic, then it may indicate the perception of Sheremet’s personality by a group of security officials and politicians associated with the Narodny Front during the 2016 political crisis.

Interestingly, at the beginning of 2017, key persons in the Ministry of Internal Affairs claimed that one of the versions of the murder of Pavel Sheremet was an order from Russia. “The investigation does not rule out the version of a contract political murder, the order for which came from the Russian Federation,” said the head of the department, Arsen Avakov. And his deputy Vadym Troyan argued that “most of the evidence points to the fact that there is a Russian trail.”

Nevertheless, the investigation, for some reason, did not get caught up in this “trail”, and at the end of 2019, already under President Zelensky, the group of volunteers who had killed Sheremet allegedly because of his fascination with “ultra-nationalist ideas” were called guilty. In the case that the investigation team has built, there is a lot of weak, circumstantial evidence, with which even deputy interior minister Anton Herashchenko does not argue.

But more importantly, the investigation ignores the political context of the murder of Pavel Sheremet, although its study could, in our opinion, lead to the real organizers of the crime.

When, in December 2019, the heads of the security agencies of Ukraine announced a breakthrough in the Sheremet case and the arrest of suspects, the Prosecutor General’s Office had already for several months had a complaint from the victim’s lawyers addressed to him and the name of the previous prosecutor Yuriy Lutsenko. The complaint referred, among other things, to the inaction of investigative actions on Matsyuk’s complaint against Maksym Zotov, as well as to the lack of progress in the version voiced in this investigation by Zaborona. We have no information that any action was taken on this complaint.

We hope that the involvement of the persons mentioned in our investigation in the Sheremet’s murder will be verified, and that the innocent will be cleared of suspicion.