PHOTO: The trial of political prisoner and citizen journalist Irina Danilovich in the Feodosia City Court in Crimea on 27.12.2022. (The Crimean Process).

AUTHOR OF THE REPORT – HUMAN RIGHTS CENTRE ZMINA

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Russian-occupied Crimea, 164 cases of attacks/threats against professional media workers and citizen journalists, editorial offices of traditional and online media outlets, Telegram channels, and online activists, were identified and analysed in the course of the research for 2022-2023.

Data for the study were collected using content analysis from open sources, which were additionally verified, as well as from the ZMINA Human Rights Centre’s own fieldwork data. A list of the main open sources is provided in Annex 1.

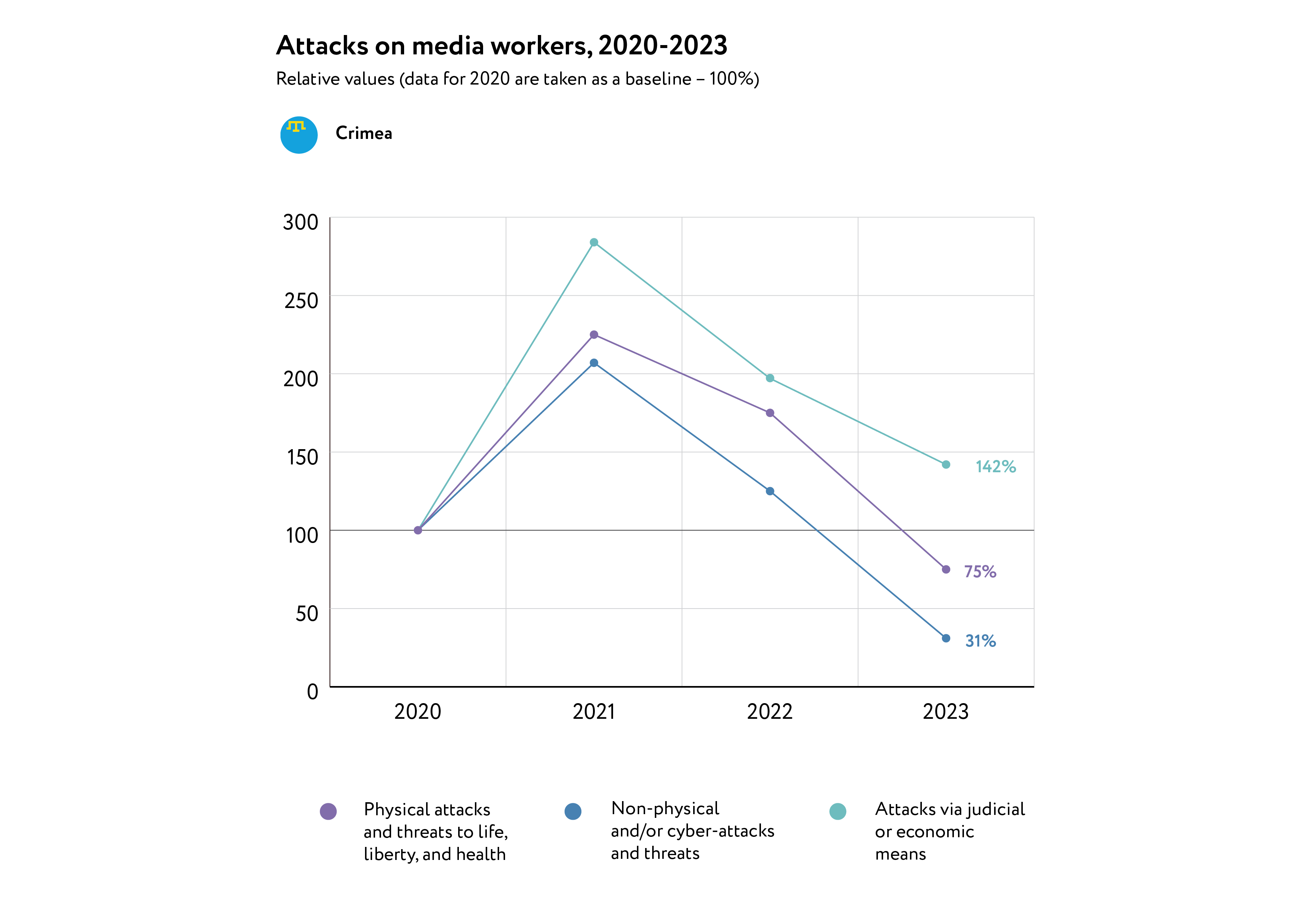

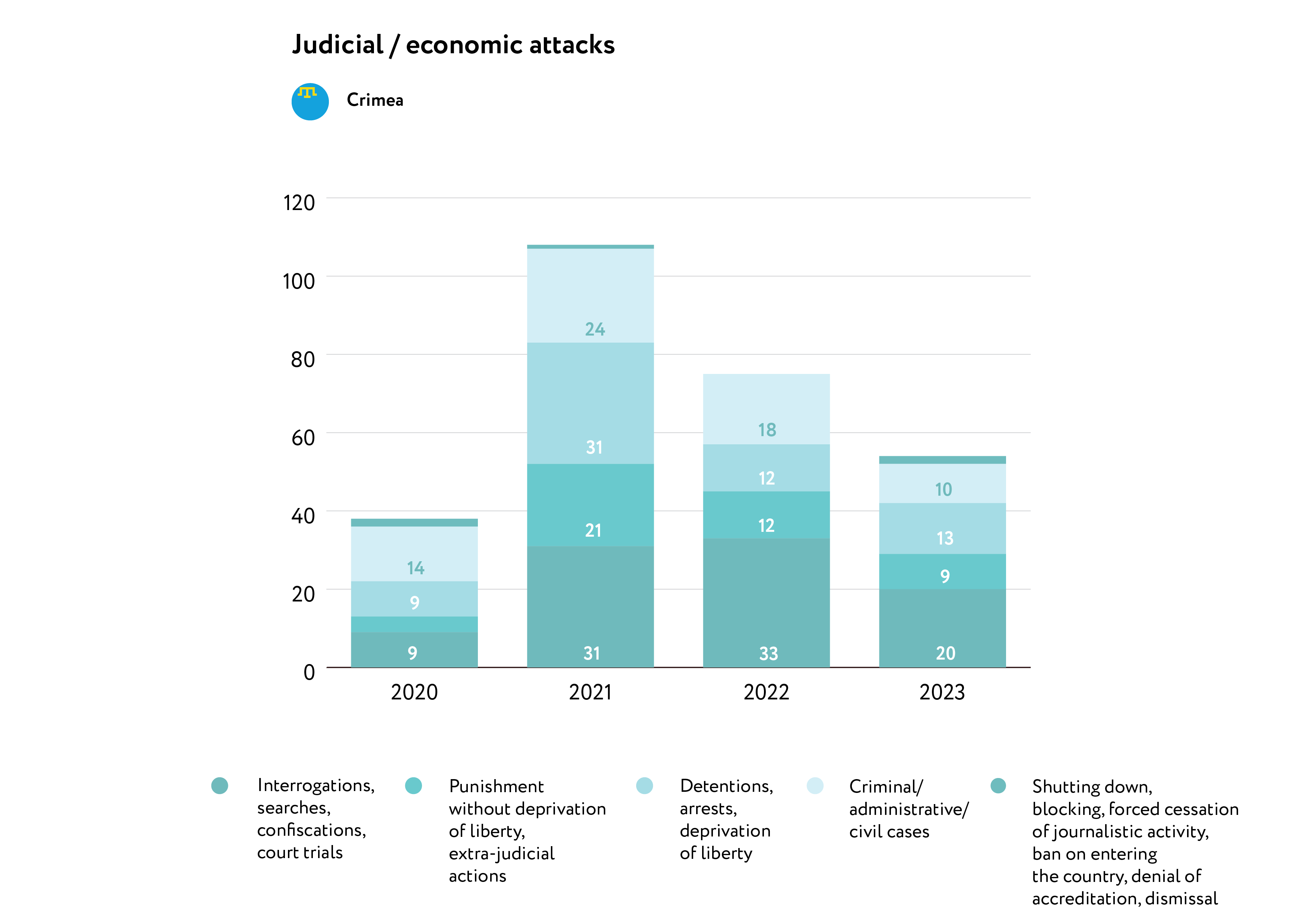

- As in previous years, attacks via judicial and/or economic means remained the main type of attacks against media workers, bloggers, and online activists in Crimea. In 2022-2023, such attacks made up 78% of the total number of incidents.

- Authorities continue to pose the largest threat to media workers and online activists in Crimea. The most common methods of pressure were arrests and fines for administrative offences, as well as the criminal prosecution of journalists.

- Since the occupation of the peninsula by the Russian Federation in 2014, a total suppression of independent journalism and attempts to establish full control over the media has continued. At the same time, there has been a decrease in the overall number of attacks (164 cases in total in 2022-2023, compared to 150 in 2021 alone) due to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which in turn led to a decrease in the work of independent journalists and, at times, the complete cessation of a number of media outlets.

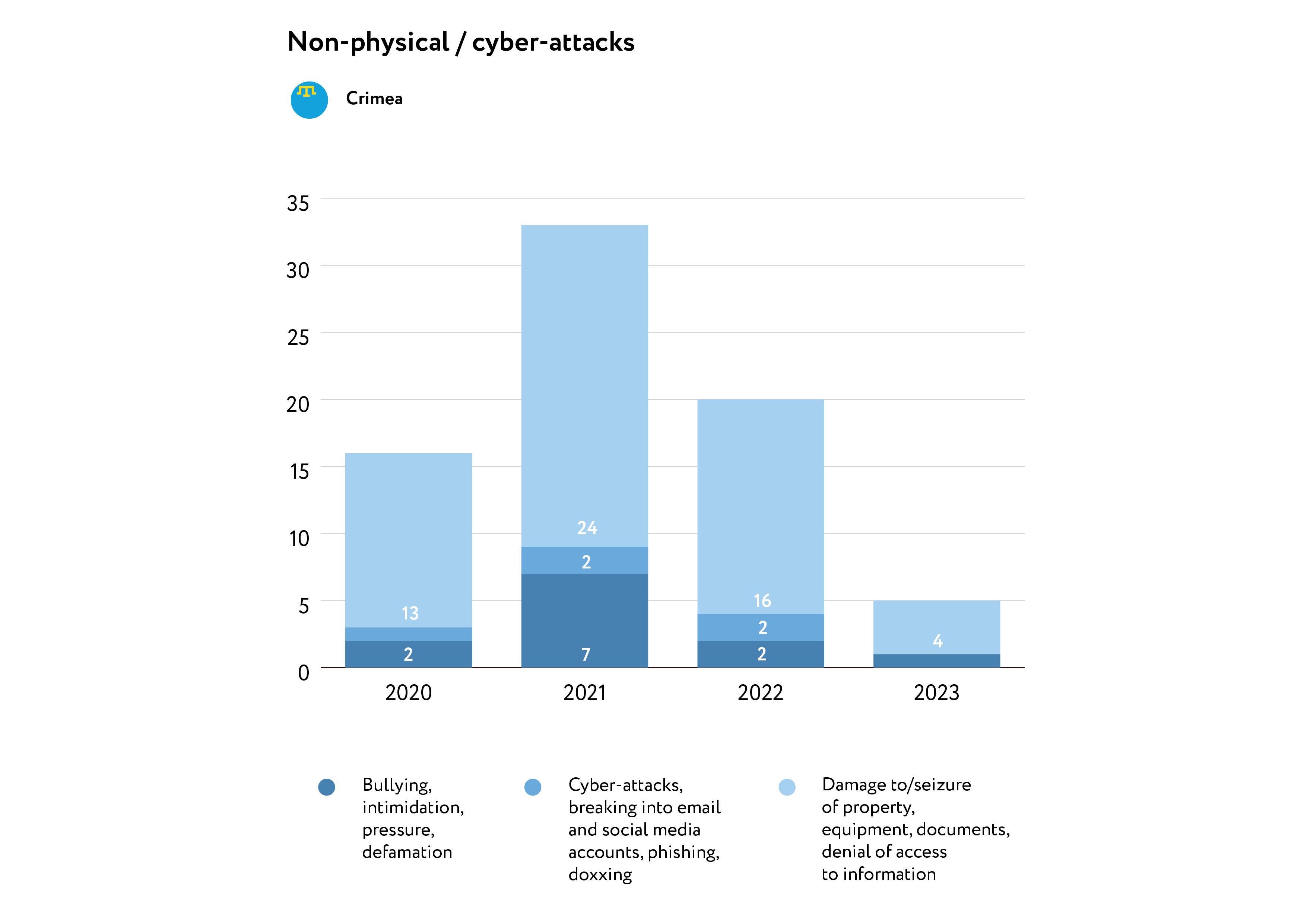

- The second most common type of pressure on media workers was non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats, in particular the unlawful obstruction of journalistic activities and denial of access to information. In 84% of cases, these threats were made by representatives of the authorities.

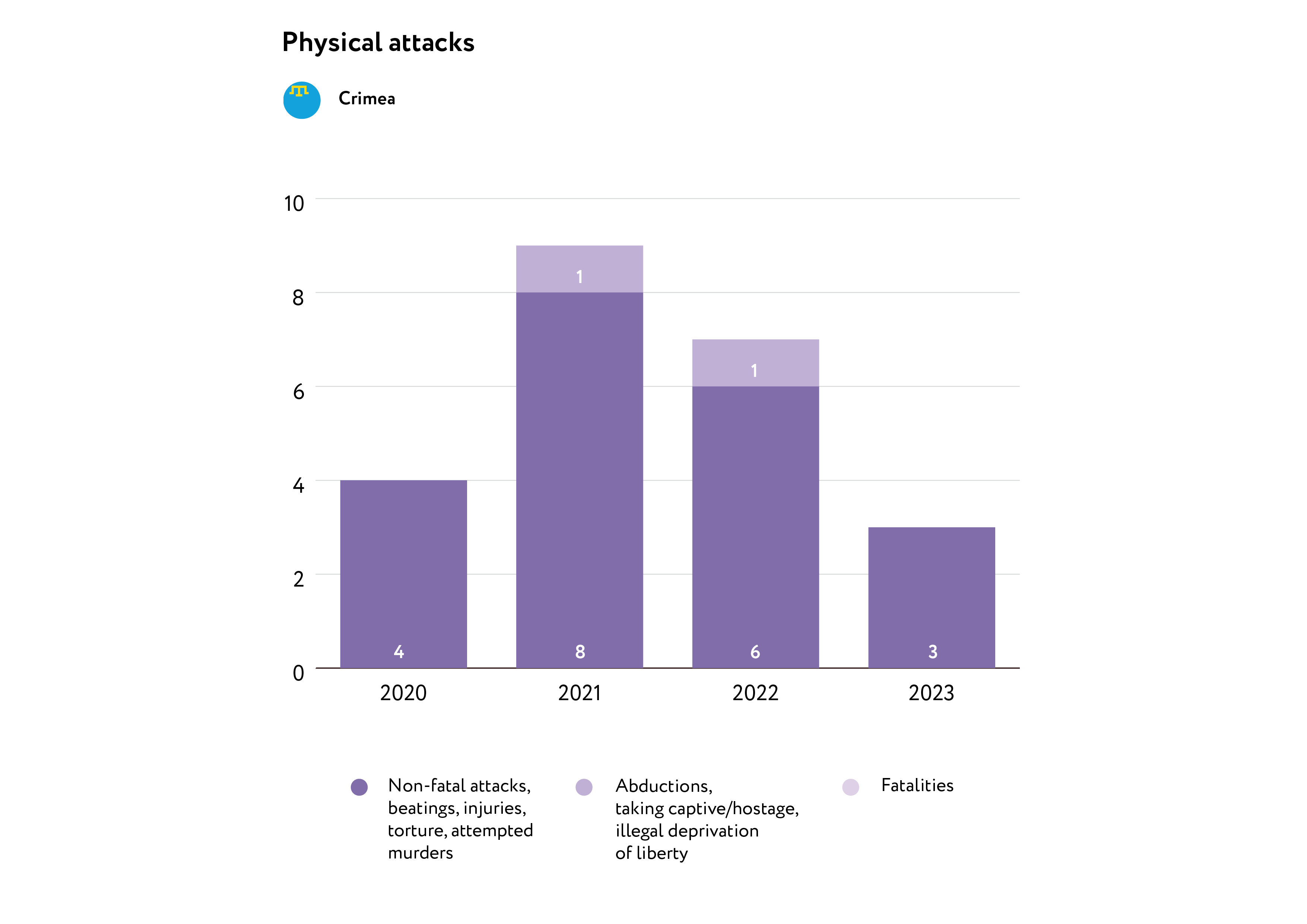

- In 2022, seven cases of physical attacks and threats to the life, liberty and health of media workers were recorded. In 2023 there were three cases, while in 2021 there were nine.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN CRIMEA

The onset of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine was accompanied by the introduction of new legislative restrictions on freedom of speech and expression. These included administrative and criminal repercussions for those criticising the military, calling for peace, or supporting sanctions against the Russian economy. In Crimea, the application of these new restrictions was accompanied by additional pressures, threats, physical violence, and even the fabrication of evidence for more serious crimes or offences.

Crimea was not studied in isolation as part of the World Press Freedom Index 2022, published by the NGO Reporters Without Borders (RSF). It was, however, mentioned as part of the research on Ukraine’s media landscape as an occupied region where the “Ukrainian media is silenced and often replaced by Kremlin propaganda.” In 2023, Crimea was not mentioned in the RSF’s report. However, it was noted that the war crimes committed by Russia have led to a deterioration in the safety of the press in Ukraine.

In the annual report of the human rights organization Freedom House on the situation with civil and political rights, “Freedom in the World – 2022“, Crimea scored seven points out of 100 and is classified as a “not free country”, with the indicators in the political rights field being in the area of negative values by two points. In the 2023 report, the situation is described as even worse – the overall score is four points, while political rights remain at the level of minus two points.

Following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the number of Ukrainian media resources blocked by providers in Crimea began to grow significantly. By the end of 2023, access to Ukrainian websites from Crimea was almost completely blocked. Social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram were also blocked, and most VPNs and apps used to bypass these blocks are still either unreliable or do not work at all.

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC AND STATE OF AFFAIRS IN THE MEDIA

On 17 March 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a legally unregulated “high alert regime” was introduced in Crimea. The exact nature of these restrictions has been changed several times, and a number of restrictions on freedom of speech continue to be in effect.

On 10 June 2020, the “Council of Judges of the Republic of Crimea” ruled out access to court hearings for individuals who are not participants in the trial. Thus, journalists were prevented from covering public trials, including political and religious persecution cases, as well as environmental damage hearings. At the same time, the judges, at their own discretion, were making decisions on the number of journalists who were allowed to attend as participants. In 2022, there were at least 13 recorded cases of preventing journalists from attending trials. The high alert regime that was used to justify these restrictions was officially lifted on 26 May 2023. However, at least four courts in Crimea were continuing to implement restrictions at the end of 2023.

LEGISLATIVE REGULATION OF THE ACTIVITIES OF THE MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS

At a legislative level, there are no legal acts specifically regulating the media in Crimea. However, a number of new regulations were adopted by Russia in 2022 which now apply to the territory of Crimea.

On 4 March 2022, Article 20.3.3 (“Public actions aimed at discrediting the use of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation in order to protect the interests of the Russian Federation and its citizens, maintain international peace and security, or the exercise by state bodies of the Russian Federation of their powers for these purposes” was added to the Code of Administrative Offenses. Two days later this article started being applied towards social media users in Crimea.

Also, on 4 March 2022, Article 20.3.4 (“Calls for the introduction of restrictive measures against the Russian Federation, citizens of the Russian Federation or Russian legal entities”) was added, but no cases of prosecution as a result of this article were recorded in Crimea.

On the same day, two articles were added to the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation: Article 280.3 (“Public actions aimed at discrediting the use of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation in order to protect the interests of the Russian Federation and its citizens, maintain international peace and security, or the exercise by state bodies of the Russian Federation of their powers for these purposes”), which mainly applied to those who repeatedly violated Article 20.3.3 or call for mass anti-war events, as well as Article 284.2 (“Calls for the introduction of restrictive measures against the Russian Federation, citizens of the Russian Federation or Russian legal entities”), which in turn applied to those who repeatedly violated Article 20.3.4.

Article 207.3 (“Public distribution of knowingly false information about the use of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation”) was also added to the Criminal Code. This prohibits the publication of any information about the actions of the Russian army which contradicts the official stance of Russian state propaganda. In 2022 at least 2 criminal cases were initiated under this article in Crimea.

On 14 June 2022, Article 275.1 (“Cooperation on a confidential basis with a foreign state, international or foreign organization”) was added to the Criminal Code. It prohibits cooperation with any foreign structures if their activities are directed against the security of the Russian Federation. At the same time, the scope and application of this article are spelled out very vaguely, opening up a wide range of possibilities for its application towards journalists who work with foreign media outlets.

On the same day, amendments were made to the content of Article 275 of the Criminal Code (“High Treason”), which was supplemented by a ban on “providing financial, logistical, consulting or other assistance to a foreign state, international or foreign organisation or their representatives in activities directed against the security of the Russian Federation”. This may also directly affect the work of journalists in Crimea.

It is worth noting the emergence of an internal departmental order – a joint order of the Office of the Judicial Department of the Republic of Crimea and the Office of the Federal Bailiff Service for the Republic of Crimea, which was issued on 25 February 2022. This document is not publicly available, however a number of judicial authorities, referring to this order, prohibited access to court buildings for those not participating in the hearings “in order to strengthen anti-terrorism security measures in court and in connection with the prevention of illegal actions on the court premises, increasing judges’ safety.” These measures significantly limited the ability of media workers to carry out their professional duties while covering prosecutions.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

Figure 1 presents a quantitative analysis of the three main types of attacks against journalists in Crimea between January 2022 and December 2023. During this period, 120 attacks via judicial and/or economic means, 25 incidents of a non-physical nature and 10 physical attacks against media workers were recorded.

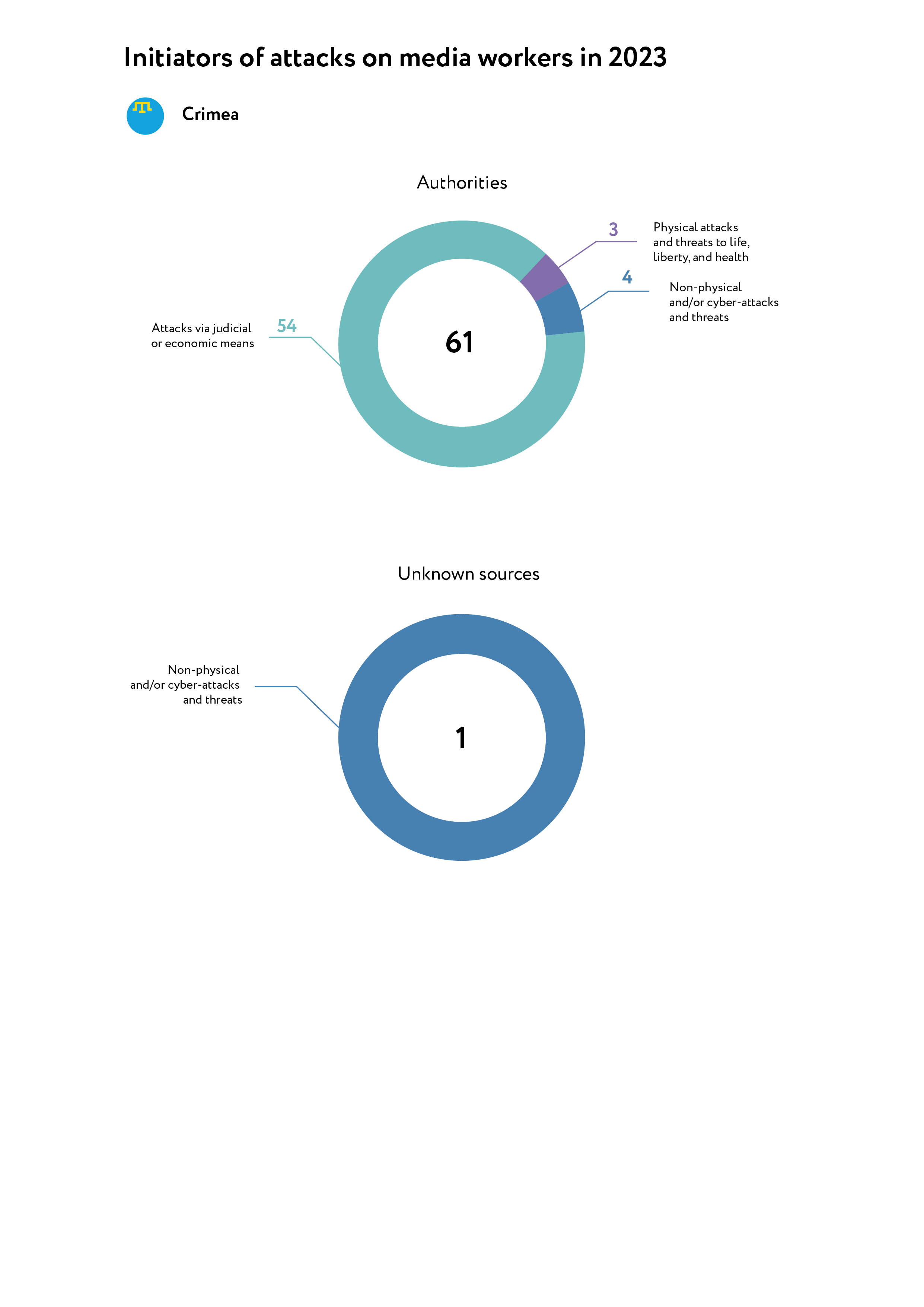

Figures 2 and 3 provide data about the perpetrators of the attacks in 2022 and 2023. As before, the authorities were the most significant cause of pressure on media workers, making up 97% of incidents in 2022 and 98% in 2023. All other recorded attacks were carried out by unknown individuals.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

In 2022 and 2023, 10 incidents involving physical pressure on media workers were reported. Among these were nine non-fatal attacks, and one incident involved abduction/deprivation of liberty. In most cases, media workers were subjected to physical pressure during arrests. All recorded physical attacks were perpetrated by representatives of the authorities.

In 2023, there was a decline in the number of physical attacks, which is associated with a general decrease in the activity of journalists in the region. Among the recorded incidents:

- On 25 January 2023, during hearings regarding a measure of restraint for the Crimean Tatars, police began to carry out mass arrests near the Kievsky District Court in Simferopol. A journalist from the human rights movement “Crimean Solidarity”, Amar Abdulgaziev, left the scene but was stopped nearby and told to produce his ID. He began to film the arrest on his phone while the Rosgvardia (Russian National Guard unit) officers twisted his hands, lifted them behind his back and took him to the prison van with the other detainees.

- On 15 March 2023, in the Simferopol district of Crimea, FSB officers searched the house of Crimean Tatar blogger Rolan Osmanov. He was immediately forced to the floor, struck several times and handcuffed. During the search, baby formula was poured on his face.

- On 5 June 2023, it was revealed that journalist Asan Akhtemov, who was part of a politically motivated criminal case, was severely beaten during his transfer to pre-trial detention centre No. 2 in Simferopol. He was assaulted by the detention centre staff, who also used a stun gun on him. This information was later confirmed by Asan Akhtemov’s lawyer.

In 2022, there was one incident involving punitive medicine that did not result in death:

- On 15 November 2022, it was revealed that Vilen Temeryanov, a citizen journalist from “Crimean Solidarity”, was sent for a compulsory psychiatric examination, which included detention in a psychiatric hospital for at least 21 days. Temeryanov was arrested in August 2022 on suspicion of terrorism.

Other incidents recorded in 2022 include:

- On 12 April 2022, FSB officers detained online activist Ilya Gantsevsky in Kerch on suspicion of breaching Article 207.3 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (“Public dissemination of knowingly false information about the use of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation”). During his arrest, excessive force was used against the activist – he was thrown to the ground and hit several times in the head and torso. Later, in a video confession, an abrasion can clearly be seen on his head.

- A month after the arrest of blogger Alexey Yefremov, it was discovered that he was assaulted during his arrest on 16 April 2022.

- On 29 April 2022, citizen journalist and activist Irina Danilovich disappeared for almost two weeks after being detained. Her lawyer stated that before a measure of restraint was chosen on 7 May, she was held at the FSB headquarters in Crimea. According to her, she was fed once a day and held in the basement of the FSB headquarters in Simferopol for eight days – from 29 April until she was taken to court. A bag was put over Danilovich’s head, and they threatened to take her “into the woods” or to the besieged southern Ukrainian city of Mariupol if she hid any piece of information.

- On 28 July 2022, citizen journalist and activist Irina Danilovich managed to send a letter from the pre-trial detention centre, in which she reported that on 5 July, FSB officers tortured her while escorting her to a court hearing regarding an extension of her measure of restraint. As an expert from “Justice for Journalists” discovered, the journalist’s handcuffs were deliberately tightened for the entire duration of their transportation.

- On 13 July 2022, near the Supreme Court of Crimea in Simferopol, blogger Rolan Osmanov was told by personnel from the Centre for Combating Extremism that he was being detained. At the same time, several people in balaclavas ran up to Osmanov from behind, twisted his arms behind his back and threw him to the ground. He was then handcuffed and forced into a car belonging to the Centre for Combating Extremism.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

Figure 5 presents non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats. The most common method of pressure on media workers and online activists was the illegal obstruction of journalistic activities and deprivation of access to information (20 incidents). There were also two cyber-attacks and three cases of harassment and defamation against media workers. In 84% of cases, these attacks were carried out by the authorities, in all other cases they were perpetrated by unknown individuals.

Obstruction of journalistic activities mainly manifested in the actions of court bailiffs, who prevented journalists from attending political trials, and judges, who rejected petitions for photography, video recording or the presence of journalists at court hearings. However, there were also cases of police banning filming in public places. Some of these incidents include:

- On 11 February 2022, Russian police officers in Simferopol detained three Crimean Tatar citizen journalists from “Crimean Solidarity” (Ali Suleymanov, Amar Abdulgaziev and Rustem Useinov), who arrived at the building of the Crimea Garrison Military Court during the sentencing of Crimean residents Zekirya Muratov and Vadim Bektemirov by the Southern District Military Court of Rostov-on-Don. Russian security forces tried to take away the journalists’ video equipment and also refused to let them into the courtroom. Subsequently, all the journalists were taken to the police station, held there for about two hours, and later released without charge.

- On 15 February 2022, during a court hearing in a criminal case against journalist Vladislav Yesipenko, Judge Dlyaver Berberov refused to approve a photography request from “Crimean Solidarity” citizen journalist Zedin Adzhikelyamov. The judge also refused to allow the journalist into the courtroom, citing a decision by the Supreme Court of Crimea, where it was recommended that individuals not participating in the case should not be allowed to be present at the hearings.

- On 6 April 2022, in Simferopol, before hearings regarding the appeal of activist Georgy Semenov, bailiffs from the “Supreme Court” of Crimea did not allow the journalist into the building, citing coronavirus restrictions.

- On 28 May 2022, in Simferopol, during a court hearing regarding an administrative case against lawyer Ayder Azamatov, the defence filed a motion to allow “Crimean Solidarity” journalist Kulamet Ibraimov into the courtroom. Judge of the Central District Court of Simferopol Sergey Demenok rejected this petition on the grounds that the journalist could take photos and videos despite the fact that the corresponding request was rejected by the court earlier.

- On 24 October 2022, at the Feodosia City Court in the case against citizen journalist Irina Danilovich, the court rejected the petition from a “Grani.ru” correspondent to attend the meeting and take photos and videos. Explaining her refusal, Judge Kulinskaya stated that the petition did not contain the digital signature of an authorised person, despite there being no such requirement for processing petitions in the legislation.

- On 7 November 2022, at the Feodosia City Court in the case against citizen journalist Iryna Danilovich, the bailiff insisted that participants, in particular “Crimean Solidarity” citizen journalist Lutfiya Zudiyeva, be prohibited from taking audio recordings without the permission of the judge. These requirements do not comply with current legislation.

- On 2 May 2023, in Simferopol, during the court hearing regarding an appeal against the arrest of Crimean Tatar human rights activist Abdureshit Dzhepparov, journalists filed a petition for admission to the courtroom and video recording. Judge Maryna Kolotsey refused to grant it, citing the safety of the trial participants in the absence of the state prosecution, witnesses and Dzhepparov himself.

- On 7 May 2023, in Simferopol, during the release of Abdureshit Dzhepparov after his administrative arrest, a journalist from “Crimean Solidarity”, Zidan Adzhikelyamov, was recording an interview with him when the personnel of the Rosgvardia (Russian National Guard unit) arrived. They stated that filming was prohibited but were not able to provide any legal grounds. Instead, they demanded written statements of intention from those present at the filming location. The journalist was able to leave the scene without providing any explanation.

- On 10 October 2023, during a court hearing at the Kyiv District Court of Simferopol in a criminal case against an abducted resident of the Kherson region, a correspondent from the “Crimean Process” was prevented from entering the building. The strengthening of anti-terrorist security measures was cited as a reason.

- On 4 December 2023, a journalist from the “Crimean Solidarity” initiative was not allowed into the magistrate’s court building in Belogorsk to attend a case hearing for Abdureshit Dzhepparov. The building’s security cited anti-terrorist legislation.

In 2022, two cyber-attacks were recorded. In 2023 no such incidents were recorded:

- On 17 April 2022, the website of the Saky newspaper “Slovo Goroda” came under attack. The hackers posted an article on the front page discrediting the armed forces and the government of Russia. Following an editorial decision, the site was taken down until the culprits were identified and the vulnerabilities were eliminated.

- On 30 December 2022, citizen journalist Elmaz Akimova noticed several attempts to hack her email and iCloud.

Additionally, in 2022-2023, three incidents related to bullying, libel and defamation against media workers were recorded:

- On 30 October 2023, the “Crimean SMERSH” Telegram channel, which is closely associated with the Crimean divisions of the FSB and the Centre for Combating Extremism, posted a publication stating that the “Crimean Solidarity” initiative is “an enemy organisation used by Ukraine to coordinate protests in Crimea and incite ethnic hatred.” The text contained threats towards subscribers, supporters and participants of this initiative.

- On 15 April 2022, a video with the “Sea News” logo was circulated in one of the Kerch groups on the social network VKontakte, as well as on various Telegram channels. In this video, online activist Ilya Gantsevsky is confessing to crimes. The video is captioned “A fascist was detained in Kerch,” although no references to fascist ideology are made in the video. Earlier, Gantsevsky was detained by FSB officers for several posts in which he condemned the war in Ukraine, emphasising the problem of the destruction of civilian infrastructure and calling for others to sign a petition to impeach Russian President Vladimir Putin.

- On 1 December 2022, an anonymous “independent news portal” called “Tavrichesky Courier” published an article with allegations that citizen journalist Irina Danilovich underwent training to educate anti-Russian activists, trained in “subversive activities” and used human rights activities as a cover. No references to the portal’s sources of information were provided.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

Figure 6 presents sub-categories of attacks via judicial and/or economic means. The main methods of pressure were interrogations, searches, confiscations and trials (53 incidents) and the initiation of criminal, administrative and civil cases (28 incidents).

A significant number of the attacks in 2022 were related to social media posts criticising the actions of Russian troops in Ukraine. In 2023, persecution mainly manifested in the indiscriminate detention of participants in uncoordinated mass events, including journalists who were collecting information. The most common form of attack in 2022 and 2023 were complex attacks carried out in the following sequence: arrest, initiation of an administrative or criminal case, trial, administrative arrest (or arrest on criminal charges) or a fine.

- On 18 February 2022, in Bakhchisarai, during the trial of Crimean Tatar activist Edem Dudakov, police officers and the National Guard of Russia personnel carried out mass arrests, including of the “Crimean Solidarity” citizen journalist Aziz Azizov, who was filming events. Prior to the trial, he was held at the Bakhchisarai district police station and, the next day was found guilty of violating Article 20.2.2 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“Organization of mass simultaneous stay and (or) movement of citizens in public places, resulting in a violation of public order”). This accusation led to his arrest for seven days.

- On 16 April 2022, in Simferopol, police officers aggressively detained blogger Alexei Yefremov. He was assaulted and accused of violating Article 20.3.3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (“Public actions aimed at discrediting the use of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation”). He was then taken to court to review the administrative offence report against him. Judge of the Kyiv District Court, Kateryna Chumachenko, found the blogger guilty of committing an administrative offence and fined him.

- On 16 February 2023, citizen journalist Galina Balaban was taken to court in Simferopol after being searched, detained, and charged under Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (“Propaganda or public demonstration of Nazi paraphernalia or symbols, or paraphernalia or symbols of extremist organizations”), her case was considered on the same day. The court fined her 2,000 rubles and ordered that her phone (which was allegedly used as part of the criminal act) be confiscated.

- On 27 July 2023, the police detained journalists Lutfiye Zudiyeva and Kulamet Ibraimov. They were supposed to cover the court session in the Supreme Court of Crimea in the case of the deputy chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, Nariman Dzhelal, and the Akhtemov brothers, accused by the Russian authorities of sabotage. Alongside the journalists, security forces detained 12 Crimean Tatars, including relatives and friends of the accused. On 28 July 2023, Kulamet Ibraimov was charged with repeated violations of Part 4 of Article 20.2.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (“Organization of mass simultaneous presence and (or) movement of citizens in public places resulting in a violation of public order”). The court remanded him in custody for five days. At the police station, officers tried to take Zudiyeva’s fingerprints through threats, but she refused. On 28 July 2023, the court fined the journalist 12 thousand rubles under the article on the organisation of mass demonstrations (Part 1 of Article 20.2.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses).

In 2022, the trend of accusing citizen journalists of terrorism and accusing media workers of crimes related to trafficking explosives has returned. There was one new case of this kind and two convictions in cases that were initiated in 2021.

The most egregious case was the abduction of citizen journalist and activist Irina Danilovich. On 29 April 2022, FSB officers kidnapped Danilovich and spent 6 days investigating her involvement in the activities of the Ukrainian special services. Under threat of death, she was forced to sign documents (including blank forms), after which she was accused of possessing an improvised explosive device. She was prevented from seeing her lawyer during this time. During the trial, many contradictions emerged, such as the fact that one of the witnesses in the case was a law enforcement officer. In addition, the court refused to hear evidence of 15 defence witnesses. On 28 December, the court found Danilovich guilty and sentenced her to seven years in prison and fined her 50 thousand rubles. The Court of Appeal commuted the sentence by one month.

- On 11 August 2022, FSB officers searched the house of “Crimean Solidarity” citizen journalist Vilen Temeryanov. After the search, the journalist was taken to Simferopol and detained until the trial, which took place on 12 August. The Kyiv District Court of Simferopol considered the investigator’s petition to detain Temeryanov on the grounds that he was suspected of committing a terrorist act. Judge Mikhail Belousov granted this request and detained the journalist for 2 months, until 10 October. Subsequently, Temeryanov was forcibly sent for psychiatric examination, including long-term detention in a psychiatric hospital.

- On 16 February 2022, the Simferopol District Court found “Crimea. Realities” journalist Vladislav Yesypenko guilty of storing and altering a hand grenade. Judge Dlyaver Berberov sentenced him to 6 years in a penal colony and fined him 110 thousand rubles. The Court of Appeal commuted the sentence by one year and reduced the fine to 105 thousand rubles.

- On 21 September 2022, the Supreme Court of Crimea announced the verdict in the criminal case against citizen journalist Asan Akhtemov, who was accused in September 2021 of possessing an explosive device as well as sabotaging a gas pipeline in the village of Perevalnoye. The court found him guilty and sentenced him to 15 years in a maximum-security colony. He will also have to pay a fine of 500 thousand rubles. The Court of Appeal toughened the sentence, ruling that the journalist must serve the first three years of his sentence in prison.

Many media workers have faced administrative persecution. Some of these incidents include:

- On 18 February 2022, Judge of the Bakhchisaray District Court, Gurman Atamanyuk, found Crimean Tatar activist and moderator of the “Rose Bush of Crimean Khans” group Edem Dudakov guilty of committing an offence under Article 20.3.1 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (“Inciting hatred or enmity, as well as humiliation of human dignity”) for a comment posted on Facebook in 2017. He was sentenced to 10 days of detention. On 17 February, an “inspection” was carried out at Dudakov’s home, which resulted in the seizure of digital equipment and his arrest.

- On 15 March 2022, the Bakhchisarai District Court fined public activist and delegate of the Kurultai of the Crimean Tatar people, Edem Dudakov, 1,500 rubles under Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (“Demonstration of Nazi symbols on the Internet”).

- On 16 March 2022, Judge Yevgeny Borisenko of the Belogorsky District Court of Crimea reviewed the files on the administrative offence case against human rights activist Abdureshit Dzhepparov and found him guilty under Article 20.3 of the Code of Administrative Offenses for posting a video explaining the origin of the song “Anthem of Soviet Aviators” on social media. The video included footage of planes with German crosses. The court sentenced him to 15 days of arrest.

- On 24 March 2022, Judge of the Krasnogvardeysky District Court, Kristina Pikula, reviewed two administrative cases against an active social media user and the head of the Central Election Commission of the Kurultai of the Crimean Tatar people, Zair Smedlyaev. In the first case, he was accused of discrediting the Russian army by comparing the “special military operation” to genocide. The judge fined him 40 thousand rubles. In the second case, he was accused of promoting Nazism after publishing a photograph of a Jewish synagogue with a swastika painted on its walls by vandals in 2014. The judge sentenced him to two days of detention.

- On 26 January 2023, a court in Simferopol found “Crimean Solidarity” citizen journalists Dlyaver Ibragimov, Kulamat Ibraimov and Yusup Useinov guilty of committing an administrative offence under Article 20.2.2 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Russian Federation (“Organization of mass simultaneous presence and (or) movement of citizens in public places resulting in a violation of public order “). Ibragimov was sentenced to 13 days, Kulamet Ibragimov – 12 days and Yusup Useinov – 13 days of administrative arrest.

- On 5 April 2023, officers from the Federal Penitentiary Service came to the house of Amet Suleymanov, a citizen journalist working for “Crimean Solidarity”, who was under house arrest at that time and took him into custody in connection with his 12-year sentence. Subsequently, he was taken to the temporary detention facility in Bakhchisarai. Suleymanov is suffering from multiple illnesses, including heart disease.

Under pressure from the authorities, media workers were forced to leave Crimea for security reasons. At least two cases are known:

- On 13 January 2023, citizen journalist, activist, and coordinator of the Crimean Tatar initiative “Nefes” Elmaz Akimova was forced to leave Crimea. Prior to that, police officers and staff members of the Centre for Combating Extremism regularly came to her home to verify her whereabouts. One such check-up occurred on 29 December 2022. For more than four years, police officers regularly came to her house to deliver warnings against any possible attempts to violate the law.

- On 9 February 2023, in Simferopol, staff from the Centre for Combating Extremism conducted a search in the apartment of freelance journalist Vasily Sadovsky on the grounds that his wife had previously posted pro-Ukrainian statements on social media. During the search, a laptop was confiscated. The journalist himself was then forced to leave Crimea.

ANNEX 1: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (CRIMEA)

- The Crimean Human Rights Group – an initiative made up of representatives of human rights organisations, whose goal is to promote the observance and protection of human rights in Crimea.

- The “Crimean Solidarity” Public Movement – an informal human rights organisation created to protect victims of political repression.

- “Crimea.Realities” – a Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty service; an online media outlet that covers political persecution in Crimea in detail.

- The public initiative “Crimean Process” – an association of experts and volunteers who assess the peculiarities of legal proceedings in political cases in Crimea.

- The ZMINA Human Rights Centre – a Ukrainian non-governmental organisation that concentrates on freedom of speech protection, and supports human rights and civil rights activists in Ukraine, including occupied Crimea.

- Social media platforms Facebook and VKontakte

- Free access Russian-language media on the Internet.

- Official websites of judicial bodies created by the Russian Federation in Crimea.