This story is part of the 2020 Investigative Grant Programme supported by the Justice for Journalists Foundation. The story was originally published on openDemocracy website.

The following article features 10 obituaries of journalists killed in Mexico in 2019. They are some of the 133 journalists who have been killed between 2000 and 2020.

Each one different, these are the lives of people committed to journalism at a time when this country became a battleground. Their voices were silenced, but their legacies endure. This memorial is meant to honour them forever. To view all 133 obituaries, click here.

Different, strong campaigning voices, masters of their own writing. The following are only 10 of the 133 journalists murdered in Mexico between 2000 and 2020. These are those who died in 2019.

The deaths are incomparable because each death was caused by a different enemy, in different areas in different years. But they are similar because these are all individuals who led the way in the noble goal of reporting.

Their precariousness of their position never stopped them from travelling to the remote mountains or to the underworld of the mafia. Often, they became entrepreneurs in order to have a way to publish or to present news. Others combined journalism with other trades to earn a decent income. Once gone, they left behind coverage of politics, drug trafficking, theft of public money, poverty, dispossession of the land of indigenous peoples, and the ruin of beaches, forests, and jungles.

In December 2006, the then President Felipe Calderón Hinojosa (2006-2012) and his government focused on national security policy. In less than 10 days, thanks to hasty decisions and weak indicators, he succeeded in justifying the necessity of a war against criminal groups.

Soon, he went from paperwork to the policies on the ground. Later, he denied that this was, in fact, “a war”. But by then, it was too late. Mexico had become a battleground. The violence – which had been terrible in recent years – became more and more violent and carried over into the next administration, with Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018).

Lives were shattered. Hopes were dashed. The drug trafficking business expanded at an unprecedented rate. And reporting – which aimed to reach out to those involved and tell their story – became a high-risk activity.

This is how the murders of journalists began to endlessly multiply. The stories of reporters, photojournalists and cameramen became part of a hydra-headed monster and the death count rose.

But the stories of some became diluted with time. Now to search for the traces of a journalist murdered two decades ago leads to graves that are surrounded by mystery. The murders were not followed up by the authorities, their families moved away, and their colleagues did not want to talk about, some of the cases.

In Mexico, 11 states have laws that set out protection mechanisms; two have links to the Federal Protection Mechanism established by the Ministry of the Interior. At the same time, 11 states have initiatives that have still not been approved and the remaining seven states have no protection legislation proposed. For seven journalists all of this was of no use. They were still murdered.

Nevertheless, these are the stories of their lives and the manner in which they left this world. None of these texts contain post-mortem descriptions because their aim is to preserve their memory. Their beautiful memory that ended unjustly.

Rafael Murúa Manríquez

January 20, 2019

Area of work: Community radio

2019 started sadly. Journalist Rafael Murúa Manríquez, founder and director of the first community radio station in Baja California Sur, Radio Kashana, was murdered and his body was found in the town of Mulegé, in the north of the state. He was the first journalist killed that year.

He was 34 years old and left behind three children.

In his last few years of life he was threatened on a regular basis. First by organized crime groups and then by government officials. On November 14, Rafa published a post on his Facebook account that said: “In the first fifty-two days of Felipe Prado’s (Mulegé’s Mayor) government, I have experienced more attacks and abuse of authority than in the previous six years, since I started working as a journalist in my hometown, Santa Rosalía… For the first time, expressing myself on a political issue has caused attacks on my person, my family and my property.”

The disappearance of the journalist, who was also a member of the World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters [AMARC], had been reported 24 hours earlier.

Article 19 (an international organisation that defends freedom of expression and access to information) and the Mexican branch of the AMARC, were able to document that the last time the journalist was heard from was at 8pm on Saturday 19 January.

This was reported by a family member, whose anonymity is protected for security reasons. “Rafael called me to ask if everything was all right. I did not hear anything more until 2:00 a.m. (the following day) when I received a visit from a person (whose name is also omitted for security reasons) who was supposedly with Rafael and who informed me that he had been taken away”.

The Attorney General’s Office of Baja California Sur has not received any information about Rafael’s murder.

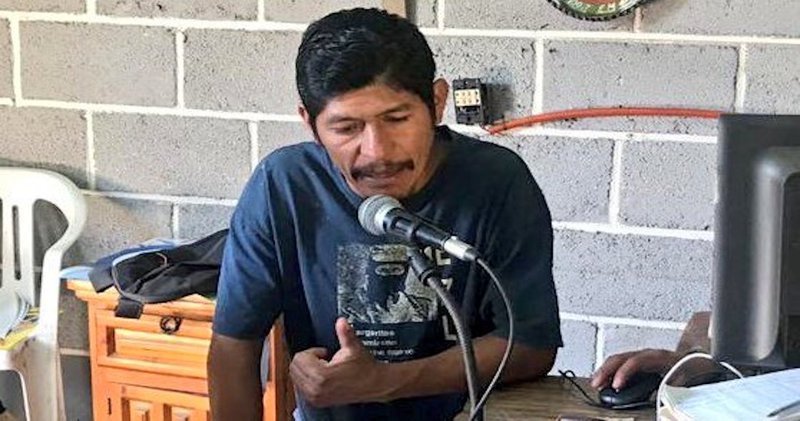

Samir Flores Soberanes

February 20, 2019

Area of work: Reporting on defence of land

Samir was shot dead at dawn on February 20, 2019, outside his home in Amilcingo, Morelos. Witnesses to the tragic event reported that the assailants fled in two cars.

Samir was an indigenous Nahuatl, born in Amilcingo. He founded Amilcingo’s Community Radio on the frequency 100.7 FM, where he hosted a program.

He was 36 years old.

When he was killed, a consultation organized by the federal government on the commissioning of a thermoelectric plant, which took place on February 23 and 24, was three days away. Samir opposed the construction of the thermoelectric plant of La Huexca, in Cuautla, which is part of the Morelos Integral Project (PIM), an infrastructure plan by the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador that also includes a gas pipeline and an aqueduct. The Federal Electricity Commission [CFE] is in charge of three Spanish companies: Abengoa, Elecnor and Enagas. Speaking on the radio, Samir was the most notorious leader of the opposition to this plant.

He was a computer technician, a sign maker, a musician and a blacksmith. He also studied a semester of law. He learned about the PIM when he attended a meeting with organic producers in Jantetelco, with others from his town. Once he heard about the subject, he make it his own.

His radio station and his leadership were born in his backyard. In 2013, Samir stood with his parents, and, a megaphone, began to report on the consequences of the PIM. This is how Radio Bocina was born, which was the predecessor to the Amiltzinko community radio station. At the time of his death, Samir was a member of the Parents’ Committee of the Amilcingo school.

Samir was married to Liliana Velázquez with whom he had four children, Amira, Jenny, Mariana and Kinith. When the tragedy of his death became public, the bells of Amilcingo were rung. And his audience, his town he had kept informed about the thermoelectric plant, was enraged forever. Anger at his death spread to residents of Morelos, Puebla and Tlaxcala, who organized themselves into the People’s Front in Defense of Land and Water (FPDTA).

But as the months went by, fewer and fewer people tuned in to Radio Amiltzinko. Broadcasting and scheduling became irregular. The Morelos District Attorney’s Office opened seven lines of investigation into this murder. Some were about the family and personal issues, including quarrels or possible debts.

One year later, and these investigations have come to nothing.

Santiago Barroso Alfaro

March 15, 2019

Area of work: Reporting on drug trafficking

Whoever killed him, knocked on his door. The journalist opened it for them, without hesitation. He was left with three gunshot wounds, one to his left clavicle and two to his abdomen.

He was 47 years old.

He was the fifth journalist killed under the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

Santiago hosted the radio program San Luis Hoy on 91.1 FM Rio Digital, was director of the news portal Red 653 and a contributor to the weekly magazine Contraseña. The first radio program he hosted was on the Radio Gallo station. Also, working as a journalist, he made extensive use of Facebook. There he broadcast his column “Sin compromisos”. One of his last articles referred to the names of a series of people in San Luis Río Colorado linked to the criminal activity of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

His excellent reporting was recognized by his colleagues in the state of Sonora. “It didn’t matter how many hours we had to wait, or how many times we had to return to an office or a point in the city to look for the information, we had to achieve our aim: to confirm the facts about complicated issues such as drug trafficking and narcotics” is how journalist Jesús Manuel Angulo described him in a profile written after his death.

Santiago graduated from the Autonomous University of Baja California (UABC) with a degree from the Faculty of Human Sciences (1989-1993). Between 1999 and 2005, he worked for the newspaper La Crónica de Baja California, where he was first a reporter and then a correspondent in San Luis Río Colorado. He published several reports on prominent men in drug trafficking, such as Ignacio Coronel, Manuel Garibay Espinoza and Eduardo Barraza “El Pony” during that time.

On December 23, 2014, Santiago reported the case of Manuel Garibay Espinoza, an alleged drug trafficker, who had been arrested in Mexicali, Baja California, in June 2014 in one of his columns. After spending almost four years in prison, he was released without criminal proceedings, despite being accused of masterminding the murder of former commander José Antonio Pineda Rodríguez in March 2002.

Seven days later, agents from the Attorney General’s Office in Sonora arrested a suspect, a city worker. The authorities reported that the main motive was an extramarital relationship. The suspect’s wife was reportedly having an affair with the murdered journalist. This completely ruled out a crime against freedom of expression. The prosecution is continuing with this line of investigation.

Telésforo Santiago Enríquez

May 2, 2019

Area of work: Reporting on drug trafficking

He was ambushed and killed in the municipality of San Agustín Loxicha, in the Sierra Sur region of Oaxaca, when he was driving to the community radio station Estéreo Cafetal 98.7 FM La Voz Zapoteca, of which he was the founder and director, and from where he fought to defend the indigenous language. He also analysed and criticized local governments.

He was 48 years old.

In addition to being a journalist, he was a teacher and was a member of Section 22 of the National Union of Education Workers.

His murder on the eve of World Press Freedom Day made him the third community radio worker and fourth journalist to be killed in 2019. He was the sixth journalist to be killed at gunpoint during the administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador. A few hours after the murder became known, the Coordinator of State Communications, Jesús Ramírez Cuevas, promised to find the culprits.

The radio station published on its Facebook page: “Those of us who are part of the Estéreo Cafetal team are shocked and outraged by the cowardly murder of our director, colleague and friend, Professor Telésforo Santiago. He was a great example of how to fight and work on behalf on his people”.

On several occasions he ran as a candidate for Mayor.

San Agustín Loxicha is one of the 570 municipalities of Oaxaca, in a mountain range beset by poverty and conflict. The guerrilla group the Ejército Popular Revolucionario (the Popular Revolutionary Army), which emerged in the 1990s, was established here. Since 1996 the state has made 250 arrests, 200 of which have been under torture. The lack of attention paid by the government to the region led to the creation of the Organization of Indigenous Zapotec Peoples (OPIZ) and other clandestine groups.

Telésforo analysed and criticised the government. He had received death threats in February.

The Attorney General’s Office of the State of Oaxaca took up the case; but so far there are no leads.

Francisco Romero Díaz

May 16, 2019

Area of work: General information

He was found dead in Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, on 115th Avenue, outside the La Gota bar. He was nicknamed the “ñaca ñaca”.

Francisco Romero was the administrator and director of the Facebook news page, Ocurrió Aquí, with more than 70,000 followers; he also collaborated with different media in Playa del Carmen.

One of his final jobs was covering a shooting that took place at the Chapultepec Brewery bar, where one person died and 11 were injured.

He gained fame for his live broadcasts from the scene. If there was a homicide, a crash or an arrest, citizens would alert him through social networks. He was the first to arrive.

His cleft lip made him even more distinctive as a journalist. He did not mind being nicknamed “ñaca ñaca”; in fact he liked it.

One of his friends and associates, Andrés Palafox, revealed after his death: “He said: if you don’t understand me it’s not my fault, it’s not my fault that you don’t know how to speak ñacañez. Because he was the ñaca ñaca and his language was supposedly ñacañez. We always played with that.”

“Ñaca ñaca” had a wife and a six-year-old son.

He had fallen in love with journalism four years earlier, almost by chance. He was riding his delivery bike when he came across an incident. A person under the influence of drugs had stolen a water pipe. Then, as he was escaping, he hit several cars on an avenue, until the police shot and stopped him. Francisco began to broadcast the event live, and the video went viral. The audience was captivated by the way he narrated the event.

The video was seen by the journalist, Rubén Pat, who sought him out and taught him the trade of reporting. They then became partners. Together they founded the weekly Playa News in 2016, which had 150,000 followers, when the population of Playa del Carmen is 200,000.

This was the beginning of the tragedy. Their reporting led to placards with threats on them, hung in the street. The Mechanism for the Protection of Journalists gave them protection, but it was of little use: Rubén Pat was killed on July 24, 2018, outside a bar, by someone pretending to be a rose seller. Francisco died a year later.

Norma Sarabia Garduza

June 11, 2019

Area of work: Police coverage

She was killed outside her home in Himanguillo by two men who shot her and then fled in a vehicle.

She was 46 years old.

Norma was the mother of a 13-year-old boy with learning difficulties, who was left without anyone to care for them after she died.

On Saturdays, she stopped reporting and attended the Universidad Popular de la Chontalpa, Tabasco, where she was about to graduate in psychology. She wanted to be a teacher once she got her degree. After the murder, the Tabasco Hoy newspaper, owned by the Cantón Zetina family, issued a statement condemning the crime, recognising Norma as an employee who had been working there for twenty years.

But in a public letter posted on Facebook, her sister Maty said this wasn’t the case. She also stated that the company had never contacted the family, not even to offer condolences. Norma also wrote for Diario Presente. Before that, she worked as a secretary at the Ramón Herrera primary school in Villa Chontalpa, Huimanguillo. She came from a family with few resources, worked as a teenager selling food in a street stall and helped her mother, María Inés Garduza, and her six siblings.

As a journalist, she wanted to specialize in covering the police. She had always been reluctant to cover political issues or any other type of news.

In 2014, Norma went to the Prosecutor’s Office and reported Héctor Tapia Ortiz and Martín Leopoldo García de la Vega, director and deputy director of the Huimanguillo police. She had been receiving threats since January 2019, when she covered an alleged kidnapping involving police officers.

According to the complaint, these two individuals accused her of extortion, and also spread messages in the town that she would be ” arrested”. The complaint was recorded in the preliminary investigation PGR/TAB/CAR-II/121/2014. Neither the report of the threats nor her murder have made any progress.

Rogelio Barragán Pérez

July 30, 2019

Area of work: Police coverage

Rogelio was kidnapped for 24 hours and then killed. His body was abandoned in the trunk of his own car, a grey Volkswagen Jetta, in the town of Zacatepec, Morelos, where his mother and a sister lived. There was evidence of torture.

His mother identified him, and she was the one who took charge of the body. Rogelio had no wife or children. One of the lines of investigation after the murder, according to the Guerrero Public Prosecutor’s Office, was his affair with a woman who lived in Zacatepec.

Rogelio Barragán was director of the news portal Guerrero al Instante in Chilpancingo, which confirmed his death. The journalist wrote articles for the judicial and police sections. With his death, the site remains, but now publishes more and more anonymous contributions and adopts a cautious tone in its news reports.

Rogelio was 47 years old and became the tenth journalist to be killed during the administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

Rogelio had been working as a journalist for more than a decade in the region. He collaborated with media such as Ecos de Guerrero and Agencia Informativa de Guerrero.

After his death, which turned Mexico into the country where most journalists have been killed in the world, the international organization Reporters without Borders reported that Rogelio had decided to stop putting his name to his articles for security reasons, as were other colleagues from the same media organisation.

One of Guerrero al Instante’s collaborators announced that two days before he was killed, Rogelio had requested help from the Federal Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists of the Federal Government. He told them that he had received death threats and needed to leave Chilpancingo. The process was very bureaucratic. They asked him to write a petition for assistance, which would describe what had happened and said they would contact him to let him know if his request was granted.

Rogelio didn’t live to find out the answer.

His murder is in a file in the Guerrero District Attorney’s Office. There are two separate lines of investigation. One focuses a possible crime of passion; the on the possibility that he was as a result of his status as a journalist. The Prosecutor’s Office has even identified a woman as the perpetrator of the murder, but it has done nothing.

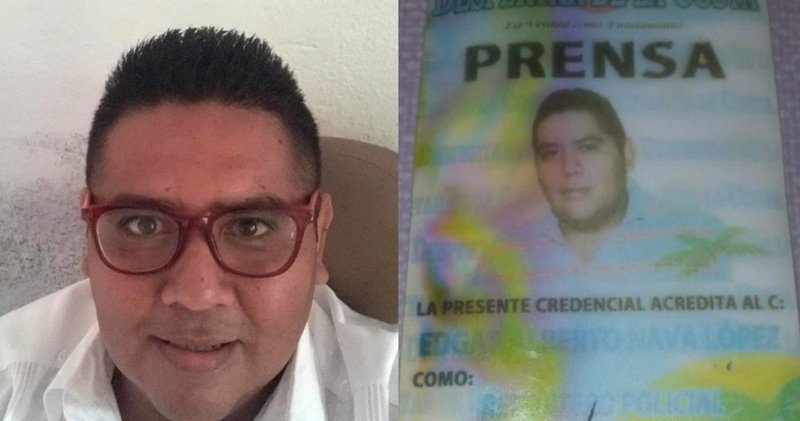

Édgar Alberto Nava López

August 2, 2019

Area of work: Police coverage

Edgar was shot at the Casa Arcadia restaurant and killed immediately. He was returning from the beach, where he had taken a trip with a group of children, as part of a program of activities for holiday makers. His body was left between the tables at the restaurant. Nava Lopez had been managing Zihuatanejo’s Facebook page, La Verdad de Zihuatanejo, for five years and was the director of Industrial Commercial Activities and Public Entertainment for the Zihuatanejo City Council.

Edgar Alberto Nava López worked both as a journalist and in public office, a frequent occurrence in southern Mexico. The difficulty of earning a living from journalism in Mexico is even more acute in the rural areas of the country.

The region where Edgar Alberto worked is where 43 students of the secondary school ‘Raul Isidro Burgos’ disappeared in 2014. It is still unclear exactly what happened to them..

La Verdad de Zihuatanejo was in charge of broadcasting news about the municipal government, as well as issuing press releases. He wrote above for social media.

His death was reported on Twitter and Facebook by the organization Displaced and Assaulted Journalists AC. They published Edgar Alberto’s face, next to his press credentials.

As a civil servant, one of his duties was to issue permits for night clubs.

Edgar Alberto’s family asked for protection through the National Union of Press Editors and tried not to appear in the media too much after he was buried. The agency asked both local and national authorities for precautionary measures and offered all the assistance of the law as victims “in the face of the incessant violence that reigns in the country, where being a journalist is more dangerous than being a criminal”.

But secrecy covered the case of silence, as is often the case with other deaths of journalists. The Guerrero Public Prosecutor’s Office took up the case but has provided no breakthrough.

Jorge Celestino Ruiz Vázquez

August 2, 2019

Area of Work: Policy coverage

Jorge was shot dead inside his own home, in Actopan, Bocanita.

Veracruz, which has become a main site of violence and the murder of journalists, lost one of its oldest journalists in Jorge. He was the first journalist to be killed by the state administration of Cuitláhuac García Jiménez, of the National Regeneration Movement, the party founded by Andrés Manuel López Obrador and which took him to the presidency.

He worked for El Grafico de Xalapa and through his reporting he was determined to reveal the corruption of the Actopan mayor’s office. At 60, and with 30 years of experience, he worked for several Veracruz media outlets and understood the problems of his region well. His neighbours remember him because he helped stop the construction of a chicken farm that the people of La Bocanita opposed.

In the final year of his life, he survived being shot at whilst in his car, according to complaints he filed with the Veracruz Attorney General’s Office [FGV]. After his death, the State Attorney General ,Jorge Winckler Ortiz, said the Secretariat of Public Security (SSP) had refused to provide him with protection.

But the SSP responded immediately in a statement sent out to the media. It claimed that it had provided surveillance around his home. They revealed that they had received official requests from the Prosecutor’s Office to protect him after he documented criminal offences by the mayor of Actopan, José Paulino Domínguez. They went on: “out of respect for the journalist and his family, this will be the last time that the unit will deal with the case. The SSP will no longer lend itself to the media actions of the FGE, which uses these extremely sensitive issues for political purposes”.

Veracruz Governor Cuitláhuac García Jiménez wrote on Twitter: “We condemn the cowardly murder of a local media correspondent, Jorge Ruiz. We will find those responsible; his murder will not go unpunished. We have been following a coordinated operation to capture the culprits for hours.”

In November, the FGV arrested one person in connection with criminal proceedings 379/2019; but he has not yet been sentenced. Nothing is known about the perpetrator. The family prefers to remain anonymous.

Nevith Condés Jaramillo

August 24, 2019

Area of work: Police coverage

His body was found one morning in the village of Cerro de Cacalotepec, in the State of Mexico, with at least 100 injuries from a sharp object; four of them serious.

Condés Jaramillo thus became the fourth Mexican journalist to be murdered in August and the tenth in 2019, according to the NGO, Article 19. His death sent a clear message that violence against journalists has not come to an end just because someone from the Left, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, is President

Condés Jaramillo was 42 years old.

He lived in Tejupilco, a town of more than 70,000 inhabitants in the south of Mexico. He is survived by his mother, Maria Lourdes. He was single and lived alone.

His journalistic work concentrated on Tierra Caliente, which is made up of several communities in the states of Guerrero, Michoacán and Mexico. These have been hit by high levels of violence in recent years. The main issues have been drug trafficking and the stripping out of natural resources.

Through El Observatorio del Sur – a Facebook page he created – Condés Jaramillo was one of the first to report on the helicopter crash in the community of Sultepec, following the shooting that broke out over the pursuit of a member of the “La Familia Michoacana” cartel by the state police in June. He also wrote about police extortion, failure to provide public services and other citizen complaints.

At his memorial service, the residents of Tejupilco paid tribute and recognized his brilliant coverage of social issues.

Five days after the murder, the Attorney General of the State of Mexico, Alejandro Gómez Sánchez, reported that there are three lines of investigation into the murder. One is personal and the other is related to his activity as a journalist.

This article is part of a SinEmbargo.MX anddemocraciaAbierta research project, supported by the Justice for Journalists Foundation.