This investigation is part of the JFJ Investigative Grant Programme and has been originally published on The NewsHawks website.

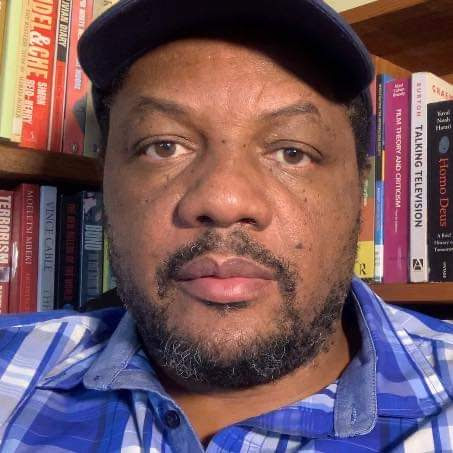

HOPEWELL Chin’ono, one of Zimbabwe’s most prominent journalists, is paying the price for his robust stance against the looting of state resources by a parasitic elite.

On the night of 30 September 2021, during a trip to France where he had been invited by the French government to attend the France-Africa Summit, he remarked that he was looking forward to enjoying some peaceful sleep for the first time since January.

“Tonight I sleep well without any alarms to worry about, no CCTV security system to check, no need to worry about a sinister regime. The first time I have slept with ‘both’ eyes closed since 5 January when I was in South Africa. We need a better country where we are not scared of the government, where we turn to the government for protection, not a regime that threatens our wellbeing.”

The poignant remark was telling. At his home in Harare’s Chisipite suburb, Chin’ono has been forced to spend thousands of US dollars on an elaborate security system including closed-circuit television cameras (CCTV) and an alarm network powered by off-the-grid energy.

In recent months, he has posted social media updates on his two recently acquired Boerboel puppies, named Buju and Shabba after the Jamaican reggae stars Buju Banton and Shabba Ranks. The Boerboel is a large, mastiff-type of dog breed with jaws powerful enough to kill some dangerous African animals. The dog is adept at aggressively fending off intruders. Chin’ono once quipped that after he has diligently taken care of the puppies since they were young, it is now the dogs’ turn to look after him. They had turned five months old by October 2021 and were beginning to look quite menacing.

His fears are justified. In January 2021, he was arrested for the third time in six months—highlighting his troubled relationship with the authorities. On 20 July 2020, police stormed his home, shattering a glass door and barging in without a search warrant. The Harvard University Niemann Fellow tweeted the raid live as it unfolded.

The police confiscated his camera and other equipment and are refusing to hand it back.

“I don’t have a camera. All my equipment was taken away by the state, arbitrarily, for no reason.” His lawyer has written to the police three times, demanding the return of the equipment, but they have ignored the letters.

He spent 84 days in pre-trial detention at Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison in Harare, where his life was in grave danger at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. Chin’ono faces three separate criminal cases and could be jailed for 26 years if convicted.

Chin’ono is convinced that he is being targeted for exposing corruption. He particularly traces the source of the government officials’ hostility to an exposé on a US$60 million public procurement scandal involving the purchase of personal protective equipment for health workers. He was credited, alongside other journalists — notably ZimLive editor Mduduzi Mathuthu — with exposing the Draxgate corruption scandal which led to the sacking of Health minister Obadiah Moyo.

“Before the Draxgate issue I am sure we can all agree that I was never attacked even when I was talking about hardcore politics. I would go and film hospitals with no medication, they would never respond to that. The minute I started working on the Draxgate issue, it was like I had touched the lion’s tail,” Chin’ono told our news crew in an interview.

On 2 November 2021, which is commemorated as International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists, Zimbabwe’s Information, Publicity and Broadcasting Services minister, Monica Mutsvangwa, said the government was making efforts to create a conducive working environment for journalists.

“We seek to remove anything that hinders the work of the media. We are open, transparent and supportive of the media,” said the minister.

She said the government does not condone any acts of violence against media practitioners.

On that same occasion, Unesco director-general Audrey Azoulay communicated a message via Unesco’s regional southern African information adviser Al Amin Yusuph, underlining the important role of the media in speaking truth to power.

“For too many journalists, however, telling the truth comes at a price. Truth and power do not always go hand in hand,” said Unesco.

The Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights — which defends people who are persecuted for doing public-interest work – said there is a “disturbing culture of impunity for attacks and crimes against journalists” in the country.

“Journalists have been subjected to arbitrary detention, arrest and prosecution, assaults, harassment, abductions, confiscation of their tools of trade and other equipment and threats of unspecified action. Journalists have often been victimised for their work in ensuring that the authorities remain accountable to the public,” said the grouping of human rights lawyers.

Alarmed by the worsening persecution of journalists and human rights defenders in Zimbabwe, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights passed Resolution 443 on 7 August 2020. The commission urged the government to guarantee the protection of journalists from arbitrary arrest and detention.

Political analysts say the Zimbabwean government has not implemented the recommendations contained in Resolution 443, including the investigation of all crimes against journalists and prosecution of the perpetrators in order to promote justice and accountability.

In October 2021, the American Bar Association (ABA)’s Human Rights Centre issued a 29-page report titled “The Persecution and Prosecutions of Hopewell Chin’ono”.

The organisation arrived at a stark conclusion: the Zimbabwean authorities were victimising him for exposing corruption through his journalistic work.

“The Zimbabwean government appears to be deliberately misusing its criminal justice system to target an outspoken journalist who has used his social media platform to raise awareness on issues of corruption, human rights violations, and bad governance,” noted the ABA.

He was first arrested on 20 July 2020 on allegations of incitement to public violence. Barely three weeks later, he was again arrested for posts criticising the judiciary and the National Prosecuting Authority. In January 2021, he was yet again arrested for allegedly criticising the police for using excessive force against a mother carrying a child.

“Chin’ono’s arrests and current criminal prosecutions appear to be politically motivated. In particular, they appear to be in retaliation for posts he made on social media on matters of corruption and bad governance as well as his support of nationwide protests, which under Zimbabwe’s own constitution and its regional and international obligations are a violation of his rights to freedom of expression association and assembly, as well as his right to participate in the conduct of public affairs,” said the ABA.

A recurring criticism of his work — especially by officials from the ruling Zanu PF — is that he is no longer a journalist but more of an activist. They accuse him of overstepping the boundaries of ethical journalistic conduct.

Chin’ono addressed this accusation in an interview with The NewsHawks.

“Yes, I am an activist and there is nothing wrong with that. Let us say you are a journalist and you have a child who is disabled and you campaign for disability rights, what is wrong with that? I am campaigning for a better Zimbabwe.”

He said there was nothing wrong with a journalist using social media platforms to publish both news stories and opinion articles. In 2017, he had 400 followers on Twitter, but this number had since exceeded 270 000. The reason for this was simple: people find his content interesting.

“…it’s because what I am saying is resonating with people and I am able to say it in a simple way that people understand without making it complex.”

Political persecution

In an interview at his home in Harare, Chin’ono said his incessant arrests were politically motivated.

“The reason behind my arrests is political persecution which is rooted in trying to stop me and other journalists as well. They use me to send a message to other journalists that if you expose corruption — the looting of public funds, the plunder of the country’s natural resources — and you expose it in such a way that the top leaders are embarrassed, ‘we will throw you into prison’. ‘We are in control of the judicial system, we’re in control of the police, and there’s nothing that you can do’. That is the main reason and it’s also to instil the fear of God in journalists. I’ve spoken to other journalists, including young journalists, who are now afraid of touching some of the big stories. They look at me and say ‘okay, if this guy is a senior journalist in our profession and he’s arrested and they [government] get away with it, what about me, just a young guy, I’ll be in trouble’. So they end up not touching those big stories.”

He added: “It’s blatant abuse of power by the political elites to stop us as journalists from doing our work.”

The Draxgate scandal

Chin’ono’s fearless reportage via his social media handles has rattled the Zimbabwean authorities, who have marked him as an enemy of the state.

As he correctly observes, the official hostility against him escalated in the aftermath of the US$60 million Draxgate exposé which lifted the lid on public procurement corruption in the government’s Covid-19 response.

Health minister Moyo was arrested for his dealings with Drax International LLC, Papi Pharma and Drax Consult SAGL. Prosecutors claimed these companies were illegally awarded contracts by the Health ministry for personal protective equipment (PPE) without a competitive tender process. The minister would later be fired in July 2020 by President Mnangagwa “for conduct inappropriate for a government minister”.

But in a dramatic turn of events, on 7 October 2021 the former minister was acquitted after High Court judge Pisirayi Kwenda threw out the charges, ruling that they were imprecise and did not disclose a criminal offence. Previously, the Drax International Zimbabwe representative, Delish Nguwaya, had charges against him also dropped after the High Court noted that offering overpriced goods for sale was not illegal.

An exasperated Chin’ono, who had predicted that the charges against the minister would be laid out in a deliberately weakened manner, was vindicated when the minister’s trial spectacularly collapsed.

“As I told you when Obadiah Moyo was charged, the case by the state was made deliberately weak so that it failed. Even a 1st year law student would have told you that,” the journalist tweeted.

The collapse of the former Health minister’s trial left many Zimbabweans fuming. We asked Chin’ono how he felt.

“It involved powerful people and the charges were taken to court. When the charges were taken to court, it was deliberately made so weak that it would fail. When the former Health minister was charged and taken to court, I said it at the time that he is going to walk because the charges were made deliberately weak. The case and its facts are there; you don’t need to be a trained prosecutor to go and charge him and get a conviction if the real facts were put on the charge sheet, but they were not put because it’s meant to protect the political elites. That’s the tragedy of Zimbabwe where state institutions are captured by the political elites and they do as they wish to protect each other. The former president, Robert Mugabe, was removed on the premise that he was surrounded by criminals, and yet there’s not been a single criminal who has been convicted. Corruption is now on steroids, it has gone out of control.”

Citizens should do more

Chin’ono says although he is grateful for the support he receives from the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights, a grouping of lawyers which represents people being unfairly treated for doing public-interest work, he feels the citizens should be doing more to assist journalists.

“I have never really gotten support when I got into trouble, except for institutional organisations like the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights. I get support from citizens in the sense that they post on Twitter, they post on Facebook, but beyond that there’s nothing really. It’s very difficult for a lot of journalists. I’m an established journalist, I’ve had savings and I’ve worked for a long time. I have not worked since July last year [2020].

“A young guy in my position would be starving. Those are some of the things that the citizens must understand, that journalists are doing what I would call dangerous work in Zimbabwe. It’s dangerous in the sense that the state comes after them and yet when they get into that danger there’s nobody to look after their families. If they’re thrown into prison, there’s nobody to look after their families. I think citizens need to reflect on those sorts of things.”

Journalists hunted down

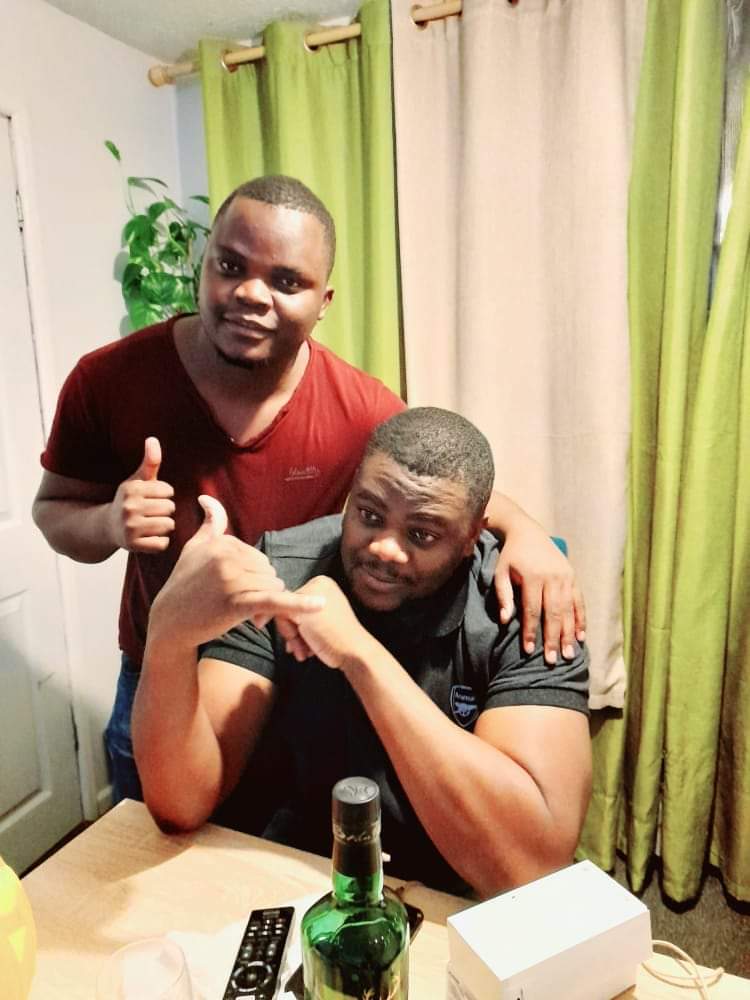

On a visit to London on 31 October 2021, Mduduzi Mathuthu, the editor of online tabloid ZimLive, bade farewell to his nephew Tawanda Muchehiwa. Muchehiwa, who hit the headlines in 2020 after he was abducted and horribly tortured by state agents who were hunting down Mathuthu, is commencing his studies at Leicester University in the United Kingdom.

What began as a horrific nightmare is now promising a glimmer of hope for better life.

“He has been through it, and I hope he peacefully pursues his dreams — we will continue with the struggle,” said Mathuthu as he bade farewell to Muchehiwa.

In the countdown to 31 July 2020 protests, the government unleashed its security forces to hunt down ZimLive editor Mathuthu who had published investigative news reports on corruption in the public procurement of Covid-19 supplies.

The journalist fled from his home in Bulawayo — Zimbabwe’s second largest city — after being tipped off about an imminent security raid. When they failed to locate Mathuthu, the Ferret team of state agents abducted his nephew Muchehiwa (22), a journalism student, and brutally tortured him for three days. He suffered life-threatening injuries and later fled into exile. The Ferret team draws its members from the police Law and Order department, Police Internal Security Intelligence, the army and the Central Intelligence Organisation.

Through investigative journalism, our team from The NewsHawks conclusively proved that a Ford Ranger truck, registration AES 2483, from the fleet of Impala Car rental, was used in Muchehiwa’s abduction. Further investigations showed that Impala is now owned by Chiltern Trust, an entity belonging to the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO).

Student leader Takudzwa Ngadziore was badly beaten up by unknown assailants — suspected to be state agents — on 18 September 2020 while addressing a Press conference outside the Impala Car rental premises in Harare. The student movement had called the Press conference in protest at Muchehiwa’s abduction and torture. Journalists attending the Press conference were also beaten up by the hired thugs, who went on to vandalise and seize their equipment.

Despite the presence of evidence — including closed-circuit television footage — Zimbabwean police have still not arrested the men who tortured Muchehiwa. Impala Car Rental resisted providing information on the person who hired their Ford Ranger. This is despite an order by High Court judge Evangelista Kabasa on 3 September 2020 directing the Sheriff to retrieve from the car rental company all documentation and information pertaining to the vehicle hire between 26 July and 6 August 2020. Names of CIO operatives working under the Ferrets — a crack security squad which features CIO, police and military intelligence agents involved in Muchehiwa’s torture — were published on social media. Former Information minister Jonathan Moyo — who has been exiled since the November 2017 military coup that toppled president Robert Mugabe — released the identities of some of the CIO operatives, namely Joshua Zingwe, Ronald Chigona and Frank Muzembi. Nobody has ever disputed the authenticity of these revelations.

After Muchehiwa’s brutal abduction and torture by state agents, his journalist uncle Mathuthu — the real target of the security operation — went into hiding. He famously announced to the world that he was holed up in “a bunker”. The government was waging war on journalists. The state agents proceeded to raid his home in Bulawayo, turning everything upside-down in the house while frantically searching for what they termed “subversive materials” which they said were designed for use during the 31 July 2020 anti-government protests.

Patriotic Bill

Zimbabwe’s cabinet recently approved a proposal to introduce new legislation — the Patriotic Bill —which will make it illegal for citizens to meet with foreign embassy officials without the government’s express authorisation. The Mnangagwa government argues that this type of law is necessary for the protection of the national interest. The authorities have since announced that they will now abandon that approach, in favour of amending existing legislation. To speed up the introduction of the draconian legislation, the government will now amend the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act to insert provisions of the autocratic Patriotic Bill.

Security hit list

Last year, the country’s security services intensified their crackdown on pro-democracy campaigners by drawing up a secret hit list featuring 20 individuals. They included opposition activists, human rights defenders and journalists.

A confidential memorandum circulated among top security officials accused “malcontents” of waging a vicious vilification campaign against President Mnangagwa, the government and the ruling Zanu PF.

“Following a JOC (Joint Operations Command) meeting held on the 10th of August 2020 on the backdrop of ongoing incessant attacks on the President of the Republic of Zimbabwe, His Excellency, Cde Emmerson Mnangagwa, the ruling party Zanu PF and the government of Zimbabwe by malcontents in Zimbabwe and in the diaspora who are working with our erstwhile colonisers to destabilise Zimbabwe and pave way for an illegal regime change, it is hereby directed that all security services be on high alert and reinvigorate efforts to stop this anti-government campaign,” read the confidential circular.

The secret security memo added: “The campaigns are not only to foment violence and sabotage government’s ongoing efforts to revive the economy but to subvert a constitutionally-elected government and replace it with foreign-funded opposition political parties. This is a direct assault on our national defence and security system.”

Prominent journalists who featured on the hit list are ZimLive editor Mathuthu, outspoken journalist and documentary filmmaker Chin’ono and Nehanda Radio editor Lance Guma. Unlike Guma who is based in the United Kingdom and is therefore relatively insulated against the excesses of an authoritarian state, Mathuthu and Chin’ono live in Zimbabwe and are at the mercy of the state apparatus.

Apart from the journalists, the list also contained the then president of the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions Peter Mutasa, Promise Mkhwananzi who leads the vocal Tajamuka pro-democracy group, outspoken ex-soldier Albert Matapo and former Zanu PF youth leader Jim Kunaka who has exposed the ruling party’s astonishing thuggery.

Social media war

Emmerson Mnangagwa, the first secretary and president of the ruling Zanu PF, is 79 years old. The median age in Zimbabwe is 19 years. The generational disconnect between young people — who constitute the majority of the population — and Zanu PF mandarins who have ruled the country with an iron fist since independence in 1980, is amplified by the growing influence of social media in political communications.

When Mnangagwa felt besieged by anti-government protesters in 2019, he arbitrarily cut off internet connectivity, sparking outrage and opening himself up to shrill criticism that his leadership was worse than that of the fallen dictator Robert Mugabe.

Government wages war against Zimbabwean journalists

One common tactic is sockpuppetry — whereby a fake online identity is used for purposes of deception. Under the cover of a fictitious identity, a hired blogger has free reign to criticise, malign, lampoon and even defame the government’s perceived opponents.

Zanu PF’s digital strategy had traditionally been rudimentary, crude and unsophisticated. The party’s founding political philosophy was anchored on the concept of centralised power underpinned by a command-and-control organisational system in which policy is not only formulated centrally but is also binding on every member.

In recent years, the regime has upped its game in cyberspace. The tactics have evolved from mere trolling. Trolls aligned to Zanu PF and the government are nicknamed “Varakashi” — from the vernacular Shona language word for “destroyers”. The authorities assembled an online brigade in the countdown to the 2018 general election. Their brief was simple and straightforward: to criticise and tarnish anyone who questions Mnangagwa’s governance ethos.

One of the most unforgettable spectacles of the 2018 election campaigns is a video of Mnangagwa personally exhorting Zanu PF youths to go out there and stamp their dominance on social media.

“We are not techno-savvy. Don’t be beaten to the game. Get in there and dominate social media,” he told the party youths.

A cyber security analyst in Harare told us that the authorities’ digital strategy is evolving. There is anecdotal evidence of the deployment of Twitter bots, which are powered by software capable of autonomously tweeting, re-tweeting, liking, following and unfollowing other accounts.

Defence minister Oppah Muchinguri-Kashiri is on record as warning that anti-government campaigners who operate on social media will soon be silenced.

On 3 March 2020, the then commander of the Zimbabwe National Army Edzai Chimonyo told senior commissioned officers at the Zimbabwe Military Academy that social media was now a national security threat and should be monitored closely.

“Social media poses a dangerous threat to our national security. Social media is one tool that is being used for misinformation,” said Chimonyo, who would later die in 2021.

The Media Institute of Southern Africa (Misa) expressed concern over the army commander’s assertion that social media is a threat to national security and that soldiers must actively monitor cyberspace. Misa said the regulation of digital security must be left to the civilian arm of the government which already has a ministry in charge of information communication technology.

The University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab—which investigates digital espionage against civil society—says seven African governments are using Israeli spyware tools to snoop on pro-democracy campaigners. Zimbabwe is one of them. Three platforms of the cyber-espionage software, developed by Israeli telecoms company Circles, has been detected Citizen Lab Zimbabwe. The use of one dates back to 2013, while another was activated in March 2018 ahead of general elections. Circles is affiliated to the NSO Group, whose Pegasus spyware has been extensively used to snoop on journalists and human rights defenders worldwide.

As the crackdown on dissent intensifies, the National Assembly approved the Cyber Security and Data Protection Bill in the first week of September 2021. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) said the proposed law poses a threat to media freedom.

“Journalists are worried about a Cyber Security Bill that is being drafted because it would allow the security apparatus to legally spy on private conversations. The army chief’s reference to social media as a threat to national security has reinforced their fears,” said RSF.

#ZimbabweanLivesMatter

In 2020, a social media hashtag galvanised Zimbabweans into action. Fed up with a brutal government crackdown on pro-democracy campaigners, citizens rallied behind the #ZimbabweanLivesMatter movement. The hashtag trended worldwide, drawing attention to the worsening human rights crisis.

The hashtag campaign united citizens in a manner that had rarely been witnessed in Zimbabwe’s often fractured opposition ranks. The previous year — as had been the case since the country’s independence in 1980 — street protests had been violently crushed by the security forces. For a moment, ordinary Zimbabweans believed that a social media hashtag could perhaps help achieve real political change.

Global celebrities, including rappers Ice Cube, Lecrae and AKA and actresses Thandiwe Newton and Pearl Thusi appeared to lend their support in focussing the global spotlight on the plight of Zimbabweans as the security crackdown intensified.

Tsitsi Dangarembga, the celebrated author, who was arrested in the 31 July 2020 protests, said the hashtag campaign had “captured the imagination of the population”. President Mnangagwa’s government, which had marketed itself to the international community as a “new dispensation” following the toppling of long-time tyrant Mugabe in a military coup, was rattled. The proverbial mask had fallen; the world could now see the regime for what it really was.

But the government was left bruised by the hashtag campaign. The Cyber Security and Data Protection Bill, which was approved by Parliament, now awaits presidential consent. Critics warn that this legislation will punish social media users for minor infractions. This is seen having a chilling effect on journalists and human rights defenders, who are already being targeted by the authorities for their work.

Conclusion

Although Zimbabwe’s 2013 constitution expressly stipulates media freedom and free expression, the lived experiences of journalists on the ground testify to a hostile environment for the profession of journalism. Beyond domestic jurisdiction, the government also has regional and international responsibilities.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights passed Resolution 443 on 7 August 2020, urging the Zimbabwean government to guarantee the protection of journalists from arbitrary arrest and detention. The work of journalism has been criminalised.