This project is part of the JFJ Investigative Grant Programme and has been completed by Maung Zarni, a Burmese scholar activist exiled in the United Kingdom, with 35-years of experience in international affairs, activism and scholarship in Myanmar affairs. He was educated at Mandalay University, the Universities of California, Washington and Wisconsin. He is co-author with Natalie Brinham, PhD, Essays on Myanmar’s Genocide of Rohingya People (2018) and Irreverent Essays: Myanmar’s Enemy of State Speaks (2019). In 2012, he resigned from his Associate Professor position at the national university in Brunei, over the university administration’s attempt to censor his media appearances on Myanmar’s unfolding genocide. He has held various teaching, research and visiting fellowships at the then University of London Institute of Education, Oxford University, Harvard University and the London School of Economics, the University of Malaya in KL and the National-Louis University in Chicago, USA. His writings have appeared in the New York Times, the Times of London, the Washington Post, the Guardian, the Jakarta Post and Anadolu News.

INTRODUCTION

In their influential book Power Without Responsibility: The Press and Broadcasting in Britain (first published in 1981 by Fontana Press), the authors James Curran and Jean Seaton argues that “the influence of the media has been immense – on institutions, the conduct of affairs, and the way in which people think and act politically”. Additionally, they stressed that “the mass media and mass politics have inspired, reflected, and shaped each other more than has commonly been realized.”

The scope and focus of their media study is the British media institutions which operate within a stable democratic environment. However, their observation is applicable to journalism and media organizations in contexts where activists, citizens, and refugees learn the journalistic trade and attempt to integrate media into their democratic and liberation struggles.

This study concerns itself with the formation and uses of media outlets by the two generations of Myanmar activists, revolutionaries and exiles as they find themselves in an uphill struggle against the more than half-century-old ruthless military dictatorships of Myanmar.

From the outset the study argues that the media even in the hands of Myanmar pro-democracy activists who become citizen-journalists, and in some cases, professional journalists who achieve international recognition, the media is a double-edged sword. While the media can advance the aims of the liberation struggles, resistance movements and democratization the same media organizations can turn into a lethal weapon against the persecuted national minorities.

Myanmar’s anti-dictatorship or opposition mass media was established by the political activists who went underground or into exile in the neighbouring Thailand and India after the bloody crack drawn of the nationwide popular revolt of 1988 against the one-party military dictatorship, which called itself Burma Socialist Programme Party government (1962-88).

Additionally, through in-depth face-to-face interviews with the 3 Myanmar-dissidents-in-exile who were based in India and Thailand, the study seeks to understand the challenges and obstacles, as well as opportunities the exiled Myanmar media have had in developing their media organizations. To this research on Myanmar exile media, the author also brings his deep personal experience and reflections anchored in his 3-decades of intimate involvement in Myanmar’s opposition movement.

To understand the media landscape and the relationship between the ideologically pro-democracy public in Myanmar and their media usage, the study also draws on the research findings of a multimethod qualitative study conducted inside Myanmar in 2013 by the BBC Media Action. This BBC study focused on multi-group discussions with 1,224 representatives from several geographic regions. Although the BBC’s brief findings are about the relationship between the media and the citizen in terms of the former’s role as an indicator of citizen participation or engagement in the democratic and/or oppositional politics in the country, it provides an empirical window into the country’s media-democracy nexus. This is a crucial window for the author particularly because as a persona non grata or “enemy of the state” (and the country) – he lacks direct access the country and her people.

THE BURMESE EXILE MEDIA: THE GENESIS AND THE CONTEXT

Typically, free press and freedom of speech are among the first casualties of any military coup. Myanmar’s free press considered one of the most vibrant in post-colonial Southeast Asia fell prey to the coup regime – then known as the Revolutionary Council (RC) government following the coup in March 1962. Bent on re-inventing state organs – and civil society organizations – to further entrench the military’s initial grip over state and society at large, the RC established its political base under the banner of the Burma Socialist Programme Party following its successful coup. Accordingly, the military axed every independent cultural, political and representative institutions, including the parliament, judiciary, political parties, student unions, labour unios, ethnically organized cultural associations along with the country’s free press while criminalizing Freedom of Speech and freedom to peacefully protest.

For 26 years – from 1962 to 1988 – the people of Myanmar were subjected to massive pro-military and ethno-nationalist propaganda manufactured by the Ministry of Defence’s Public Relations Division and the Ministry of Culture and Information, both presided over, and tightly controlled, by military commanders and their loyal civilian bureaucrats.

However, the newly refashioned neo-totalitarian state never succeeded in extinguishing the fire of popular hunger for information and domestic and international news. This hunger manifested itself in the form of political rumours and gossip. An entire generation of Burmese from different ethnicities and geographic locations grew up without having any access to proper news and news analyses. The Burmese military erected its own iron curtain, and the news was what the military chose to broadcast or print. The educated or politically conscious social classes – largely urbanites – would tune into a few international radio stations, with Burmese and English language services, specifically All India Radio, the BBC World Service and the Voice of America, which could be accessed on short-wave radios.

The free press was re-born amidst the first nation-wide popular protests calling for the end of the one-party military dictatorship of the Burma Socialist Programme Party regime erupted in the summer of 1988. Burma’s people power revolt of 1988 preceded the widely televised events of the June uprisings in China and the fall of the Berlin Wall by one year. A local author – medical doctor-cum-author – compiled and chronicled the mushrooming of the locally produced news publication in some of the largest urban centres which became the hotbeds of the anti-dictatorship rallies and protests. In his compilation, this protest period of several months saw the emergence of about one dozen and more news publications in Mandala the second largest city, alone. (See the picture below of the collage of the samples of the banners of the “people’s newspapers”. During the 1988 nationwide revolt they offered their readers protest news and rumours of various political intrigues and developments within the ruling dictatorship, all triggered by the national uprisings).

Many of the Burmese publishing and writing in these “newspapers” weren’t professional journalists. They were largely the work of amateurs who realized the need for news about the uprisings in order to keep the citizenry informed about the political events aimed at ending the one-party dictatorship, with the country’s military as its backbone.

In part, owing to the popular revolt in major cities and towns and in part to the pressure from the main foreign donor – namely Japan – the leadership of the dictatorship decided to dissolve the Burma Socialist Programme Party, its political wing.

But the ex-generals-turned-socialist party leaders decided to call in its security forces, including the national armed forces, to crush the nation-wide revolt, and subsequently form another openly military junta, without the façade of the civilian rule (or rather, the rule of civilianized generals).

The bloody crackdown of the protest movement resulted in the murder of estimated 3,000 civilian protestors in different cities and towns. Once again, the new authoritarian leadership targeted the emerging media. And the emerging civil society space was short-lived. Following the crackdown, over 10,000 Burmese activists the majority of whom were high school and university students fled to several ethnic minority regions along Thai-, Indian and Chinese-Burmese borders. Having been provided sanctuary by different armed ethnic organizations in these border regions many of these formerly urban-based students banded together, and formed the All Burma Students Democratic Front (ABSDF), an armed student revolutionary organization with the avowed aim of fighting the new military junta. Of these thousands, a handful of students took refuge in neighbouring Thailand and India.

At the time, the author himself was an overseas university student in California. He observed the emergence of both the armed student revolutionary movement and the establishment of small news outlets by a few student exiles, particularly in Thailand. Like the “Free Press” which briefly saw the light of the day during the most intense protest months of July, August and September the new news outlets published news about the emerging pro-democracy opposition movement inside Burma. The old one-party dictatorship dissolved itself, and orchestrated a military take-over of the reins of the state on 18 September 1988, and killed off the emerging democratic space.

It was against this backdrop the exile media was birthed.

The coup of 1962 had triggered the outflow of dissident across Myanmar borders, particularly Thailand who set up anti-coup armed resistance movements. A small number of Western educated Burmese from different ethnic backgrounds had also established various types of news reportage. In the 1970’s and 1980’s, U Kyaw Win, professor of counselling psychology at Orange Coast College in Los Angeles, and Harn Yawnghwe of Montreal, Canada were among the pioneers who set up small subscriber-based print news updates for the Burmese diaspora. There was also news and information dissemination initiative by the Committee for the Restoration of Democracy in Burma (CRDB), the then largest political exile organization established by Western educated Burmese dissidents in exile, operating out of USA, UK, Australia, West Germany and Thailand. The CRDB published prints of its regular updates and policy analyses and distributed them amongst its members worldwide.

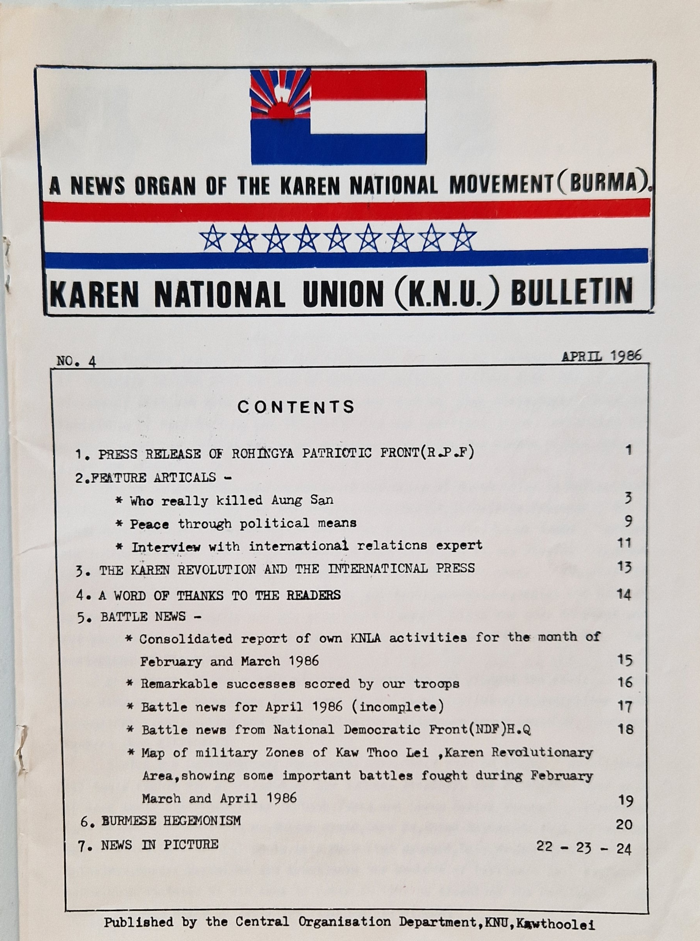

The Karen National Union, the oldest revolutionary organization, was also running its own “news service” focusing on the current affairs, serving as a voice of ethnic armed resistance organizations, including the sole Rohingya resistance group, operating out of the resistance-controlled border regions of Myanmar in the 1980’s.

There were also efforts to create Myanmar news circulars by a small number of faith-based (Christian mainly) refugee relief organizations that operated along the Thai-Burmese borders, catering to the needs of the war refuges from Myanmar.

However, their attempts at disseminating news about the current affairs of Myanmar did not evolve into a proper media outlet. When a large wave of young university-educated dissidents or university students arrived in Thailand a small number of them took up journalism as their chosen method of opposition to the new military junta, named the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) formed in September 1988. They came into contact with some Burma Watchers from amongst the Thailand-based western journalists. Their arrival in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s coincided with the emergence of commercially available Information Technology (IT).

The 1990s were a watershed period for the birth of professional but categorically anti-dictatorship exile media. Noteworthy is the fact that this exile media was midwifed by the three contributing factors, specifically Western journalists with sympathy for the young revolutionaries of Myanmar, the availability of the new IT and the Western governments’ rediscovery of “civil society” “democratic values” and “human rights”, which they shelved during half-century of the Cold War.

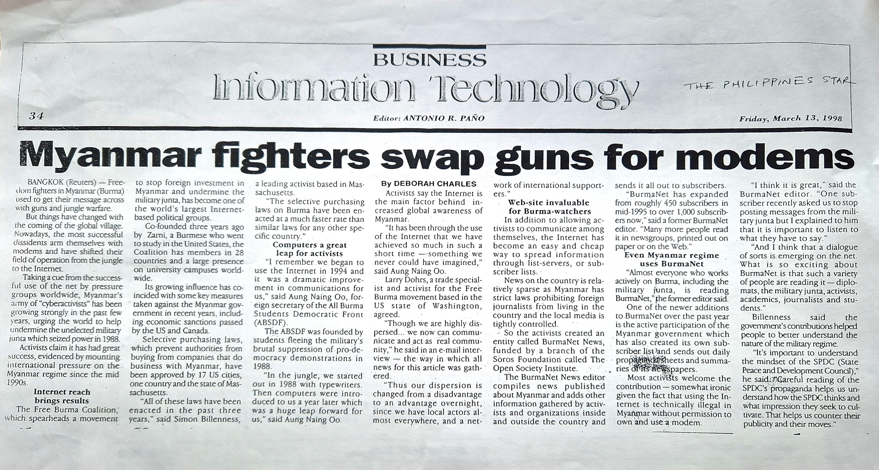

The experienced western journalists based in Chiang Mai and Bangkok, Thailand took under their wing the aspiring Burmese journalists with dissident or activist background under mentored them. Besides, and importantly, the Internet made it possible for research, information gathering, dissemination and audience- or news market-building. The emergence and widespread accessibility via the Internet service providers such as the AOL in USA had enabled both Myanmar dissidents-turned-journalists and their brethren in Myanmar diaspora to weaponize Myanmar-related information and updates in their shared goal of resisting the repression military dictatorship at home in Myanmar.

A sample reportage on how Myanmar activists were using the new Information Technology in their fight against Myanmar military regime. The Philippines Star, 13 March 1998.

The shift from the West’s Cold War policy paradigm of putting human rights and democracy on the backburner to front-loading them as a new set of conditions for Western engagement with formerly closed and neo-totalitarian countries such as Myanmar, China, the Philippines in Asia as well as formerly USSR semi-colonies of the Eastern Europe, meant there would be funding available for the development of pro-democracy, opposition outlets. Because even after the dissolution of the USSR, Myanmar continued to remain under a neo-totalitarian military junta, there was no civil society space inside Myanmar for the creation of a free media.

Additionally, the dissidents in exile found themselves in a rather conducive international environment in Thailand and India.

Among the array of media organizations set up by different exiles, three turned out to be most successful. They are the Irrawaddy News Group which began as a conduit and supplier of Burma information and updates to foreign embassies in Bangkok, and later a small circulation monthly publication; the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), the originally Chiang Mai-based Burmese opposition shortwave radio station, founded a year after Aung San Suu Kyi was awarded Nobel Peace Prize (in 1991) with the support of the Norwegian government and later with the US National Endowment for Democracy; and the Mizzima News Group, established by Burmese dissidents in exile in New Delhi, India. The Irrawaddy and the DVB were all founded around the same time in the early 1990’s while the Mizzima was founded in India in 1998.

[They had relocated their main operations in Yangon during the decade of 2010 in which Myanmar junta opened up the country commercially and renormalized its relations with the West, (which had imposed financial and economic sanctions in the previous decade), in exchange for political opening and cooperation with the main opposition National League for Democracy].

All of these main exile media outlets were grant-supported non-profit and value-driven media outlets, as opposed to sales or advertisement-driven commercial news organizations. Suffice it to say that in their three decades of operations, they have been a mainstay of news for the Burmese civil society, a large diaspora globally, international researchers and international policy makers with an interest in Myanmar affairs, international news agencies and, last but not least, Myanmar resistance at large. They have produced award-winning journalists many of whom risked their lives and imprisonment doing their job in rather challenging environments, particularly those who operate inside Myanmar during the decades of the repressive rule of Myanmar military.

Some such as the Burma VJ, a documentary about the DVB reporters risking their lives to report on the monks’ revolt in 2007 was nominated for the Oscar in the documentary category.

Some of the pioneers such as Irrawaddy News Group founder Aung Zaw, a university student activist from the 1988 nationwide uprising, were internationally recognized for his leadership in the field of Myanmar media.

During Myanmar’s decade of political and commercial opening – dubbed Myanmar Spring – which began with the military-led reforms in 2010, Stanford University’s Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center (Shorenstein APARC) recognized Aung Zaw as the 2013 recipient of the Shorenstein Journalism Award “for his leadership in establishing independent media in Myanmar (Burma) and his dedication to integrity in reporting on Southeast Asia.” The same year, he was also awarded 2014 Committee to Protect Journalists International Press Freedom Award.

The reform decade of Myanmar saw the phenomenal growth of private and independent media outlets in the country. Virtually, every major exile media outlet opened their main bureaus in Yangon, the largest city and former capital. The exiles were allowed back in by the reformist military leadership, who swapped their military uniform with the civilian attire, running the quasi-democratic government. According to the BBC Media Action study published in 2014, there were a total of 350+ private media and independent news outlets excluding the TV and FM stations which did not generate news. In those years Myanmar media was thought to be freest and most vibrant in Southeast Asia, with the military having ended its censorship as part of its reformist agenda.

This contextual overview of Myanmar exile media and its genesis will not be complete without a mention of its dark – very dark – turn. Specifically, virtually all Myanmar and Myanmar language media outlets including the award-winning pioneer journalists from Irrawaddy, DVB and, to a lesser extent, Mizzima joined hands with Myanmar military, Aung San Suu Kyi’s flagship opposition NLD party, which, after its landslide electoral victory in 2015, and the extremist Buddhist clergy in the military-organized genocide against Rohingya Muslims in Western Myanmar next to Bangladesh.

To give an example, the Irrawaddy News Group founder Aung Zaw was seen on his Myanmar language TV talk show, propagating the empirically false view – invented and peddled by Myanmar military dictatorship of the 1970’s – that Rohingyas, the target of Myanmar military’s genocide and the subject of society’s bigotry, were “jihadists” with ties to the global “terrorist organizations”. He was also promoting Myanmar military line – or lie – that genocide victims as an ethnic group were interlopers from Bangladesh, who are really “Bengali”, but assuming the “fake ethnic identity as Rohingya.”[i] During those genocidal years, the Facebook was coterminous with the Internet among Myanmar public Irrawaddy Burmese Language Facebook with its 6 million followers were extremely influential as public opinion-maker. Needless to say, the profound impact that Irrawaddy, and other leading journalists had in moving Myanmar public opinion in the direction of genocidal racism.

Some of Myanmar’s most influential and independent Burmese language media outlets – of which Irrawaddy (and DVB) were two torch-bearers – played a similarly devasting role that Radio-Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) in the Rwandan genocide of 1994. The Burmese language media outlets – some are English-Myanmar bi-lingual publications – toed the military-and-NLD joint government’s line – that the country had come under Islamic terrorist threat which called for decisive military response as “self-defence”, the view that is typically heard in the Western media, political and policy quarters these days regarding Gaza. These influential Myanmar outlets, including those which sprang up or drastically expanded, during Myanmar Spring of 2010 painted the presence of Rohingya Muslim in Western Myanmar as encroachment on the Buddhist society and Myanmar’s sovereignty.

One of Myanmar’s top news group Eleven ran this cover story, creating the non-existent link between the ISIS in Iraq-Syria region and Rohingya Muslims, who lived, peacefully, under the most destitute and oppressed conditions. The image of a burning Rohingya village torched by Myanmar military is accompanied by the caption “Myanmar’s western-most town of Maungdaw must not be allowed to fall (into the hands of the Islamic State and its proxies). Source: Eleven Weekly, 12 September 2017.

Besides these outlets affixed the label “as intellectual or activist mercenaries bought by “Muslim money” any Myanmar human rights activists who opposed what they viewed as a textbook genocide by Myanmar military and Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD government were doing to the Rohingya minority under the of “security clearance operations”. Nearly 1 million Rohingyas were violently deported across the border into Bangladesh while over 300 villages were torched to the ground by Myanmar military and local Buddhist Rakhine collaborators.

THE PERSONAL TALES OF THE THREE MEDIA PROFESSIONALS

For the JFJ-commissioned study, I had, as a matter of principle, selected only a small number of Myanmar exile journalists – one is a managerial media professional, with a strong feminist activist background while avoiding any Myanmar exile journalists who were known to have promoted genocidal racism through their craft.

In the remainder of this paper, I will briefly profile three Myanmar media professionals who have shown professional integrity in their field of mass media. Each of them shared with me in video-recorded interviews their several decades’ worth of experiences operating in the generally hostile environment in another “illiberal democracy”, namely Thailand where the country’s military backseat-drive the electoral politics, with trappings of a democracy.

Mr. Wai Moe

Wai Moe came from a political active family in the then capital Rangoon, the hotbed of anti-dictatorship opposition movement throughout the neo-totalitarian years (1962-88). He cut his activist teeth in the street protests which erupted in the spring of 1988. After initial brush with the law as a teenager, he was briefly detained and released during the 1988 uprisings. His student activism continued, however, and eventually landed him behind bars. Then he was barely 15. He spent 4 years in one of the country’s harshest prisons in a city called Myingyan, 400-miles away from his home city of Rangoon. There he learned English from older and better educated prisoner. After his release from prison, Wai Moe slipped across the border into Thailand. Using his English proficiency which he acquired during his time in jail, he began working for the Irrawaddy News Group office in Chiang Mai for over a decade. When Myanmar began its genocidal onslaught against Rohingya minority people in Western Myanmar Wai Moe left hist first media job at the Irrawaddy, which was also gaining notoriety among international journalists as a racist, bigoted Myanmar news group run by former dissidents and exiles from Myanmar. He worked as a stringer for the New York Times, and other reputable international news organizations, specifically covering racist violence against Rohingya, corruption in Myanmar and other topics of policy significance. He held a visiting fellowship with the Institute of Southeast Asia, Singapore. He lives in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

(Ms) TIN TIN NYO

Tin Tin Nyo is from Myanmar’s one of the oldest nationality groups known as Mon. The early Mons were scattered across several mainland Southeast Asia including Siam or ancient Thailand, Cambodia and Myanmar. As a group, they were noted as the earliest founders of Buddhist cultural centres and political systems in Thailand and Myanmar. Tin Tin Nyo is a well-known woman leader who led Burmese Women’s Union based in Thailand from 2015-2020. For 3 years (2007-2010) she served as a board member of the Women’s League of Burma, the umbrella organization with ethnically organized women’s activist organizations. She was involved in policy development and peace-building initiatives as they pertain to women’s issues. For the last 4 years since 2019, Tin Tin Nyo has held the position of the Managing Director of Burma News International (BNI). Tin Tin Nyo stated that her organization is committed to building a thriving network of ethnic media and advocating for media freedom and the rights and equality of ethnic nationalities of Myanmar. She is exiled in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

MR SOE MYINT (“The Hijacker”-turned-Journalist)

Of the 3 media professionals I interviewed for this study Soe Myint has the most storied life. In his TED Talk in Yangon in November 2015, Soe Myint introduced himself as “ (on 11 November 1990) I hijacked the plane – Thai Airways plane, with 220 passengers on board” to call global attention to the little-reported Burmese struggle for democracy and an end to the martial law.” The hi-jacking by the young Burmese dissident and his co-hijacker was Thailand-based Burmese student dissident in exile. Their deed was done a decade before 9-11. They forced the Thai Airway flight bound for Rangoon to reroute and land in Calcutta (now Kolkata), the eastern coastal city of India. The Indian government of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was a well-known supporter of Burmese democratic movement, and Soe Myint and his mate’s only demand was to allow them a press conference after they turned themselves in the Calcutta International Airport where they would read a pre-written press statement calling for human rights, including freedom of speech and end to the military rule. Despite their non-violent “terrorism” in the air, they were treated leniently by the Indian authorities, and in due course granted refugee status. Eight years later in 1998, Soe Myint founded what became one of the reputable on-line news groups run by Myanmar exile journalists – Mizzima News Group. The Mizzima has about 150 journalists on its payroll. The majority of these journalists are operating underground inside Myanmar including in the civil war zones. When the Myanmar military regime opened the country up for business and renormalized the country’s relations with the West in 2010, Soe Myint went home and opened the Mizzima bureau in Yangon while concurrently opening an overseas office in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

After the military coup of February 2021 which ended the decade-long Myanmar Spring and ousted the re-elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi, Soe Myint fled the country to Thailand. He is now exiled, for the second time, in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

CHALLENGES AND INSECURITIES

In this final section I offer the summary of key findings from my in-depth interviews. Instead of offering the crucial observations my interviewees made verbatim I have opted to summarize them for clarity and brevity’s sake.

- In the 1990’s when the first-generation of exiled dissidents-cum-journalists from the 1988 nationwide revolt began their media organizations (for instance, DVB, Irrawaddy, etc.) in neighbouring Thailand they had to start from scratch. No local Thai or INGO networks which the Burmese could turn to for assistance and support.

- However, like Rajiv Gandhi’s ruling Congress Party in India and its pro-democratic stance towards Myanmar, the ruling party in Thailand at the time was democratic in orientation. Accordingly, the Thai authorities were quite tolerant, if not openly supportive, regarding Myanmar dissidents operating on the Thai soil.

- Because, as a non-NATO strategy ally of USA, Thailand has always been susceptible to western pressure, especially the United States, it strikes a balance between maintaining friendly ties with Myanmar military and responding positively to the supportive US policy towards Myanmar’s democratic opposition led by Aung San Suu Kyi.

- Thai authorities’ tacit acceptance of the presence of Myanmar exiles in Thailand has afforded Myanmar exile media organizations to operate quite openly, providing that these media organizations stay clear of reporting on the domestic affairs of Thailand, for instance.

- On their part, in their reportage, Myanmar exile media organizations stay focused on Myanmar affairs. In many ways, this also serves Thailand’s needs for intelligence about the neighbour, which had long been viewed by the Thai political and military class as a historical enemy. (Myanmar and Thai kingdoms fought multiple vicious wars in the 18th century, which ended with Myanmar invaders ransacking in the 1770’s the old capital of Siam, the old name of Thailand, at Ayuttaya, about 1 hour drive from the present-day capital of Bangkok).

- The new generation of Myanmar exiles who fled the crackdown after the 2021 military coup were coming into a situation in Thailand where there have already been support networks, for instance, Myanmar-focused INGOs and Myanmar NGOs, which sprang up with funding from USA, Canada and EU over the past decades since Aung San Suu Kyi and Myanmar opposition gained international recognition and support.

- However, the lack of proper documentation – passports, Thai entry visas, work and resident permits – has been a perennial challenge for Myanmar exiled journalists.

- The silver lining is the established media organizations such as the Burma News International and Mizzima run by well-networked and savvy media leaders have devised informal working relations with local Thai authorities. This in turn enables these exile media organizations to seek assistance from local police and immigration authorities in the event some of their staff journalists get detained on grounds of illegal stay in Thailand.

- The last decade or so saw the growing closeness between Thai-and-Myanmar militaries. Myanmar military does pressure their Thai counterpart to arrest and deport some dissidents including those who are working as exile journalists.

- There have been rather dreadful incidents whereby some Myanmar exile journalists had “disappeared” while working in some Thai-Burmese border towns such as Mae Sot, in Tak Province.

- On the other hand, Myanmar exile media organizations have also built up solidarity networks with Thai local activists and NGOs based on thematic issues such as women’s or labour rights. This solidarity tie provides Myanmar journalists in Thailand a layer of assistance, support and protection.

- At the most elemental level, the Thai local police and immigration officials are open to letting go of detained Myanmar nationals including exiled journalists – the vast majority of whom are without any proper visa or documentation – in exchange for certain amount of bribe.

- Still, the precariousness of being exiled Myanmar media staff and organization weighs heavily on the minds of the exiles in Thailand.

- One new development since the coup of 2021 is the significant increase in the number of Myanmar military agents and informers in the pockets of Myanmar exiles, which are concentrated in several different cities such as Bangkok, Chiang Mai and the Thai border town of Mao Sot. This in turn increases both the psychological insecurity and the very real risk to the wellbeing of exile media professionals.

- In the Thai border town of Mae Sot where thousands of Myanmar dissidents have flooded since the 2021 coup – some waiting for opportunities to go onto third countries such as Czech Republic, USA, Canada, Norway and Germany – Myanmar exile journalists live in fear of being kidnapped by Myanmar military agents. One estimate puts at roughly 400 the number of exile Myanmar journalists who had lost their livelihoods and hence fled across the border to Thailand – because virtually all private and independent media organizations were forced to shut down by the increasingly repressive stance of the coup regime.

CONCLUSION

Ours is the age of information. Both traditional journalism – print and broadcast – and the new citizen journalism are extremely vital to keep respective public or audiences informed. Against the backdrop of “Fake News” “Alternative Realities”, media organizations that adhere to the media ethics of fairness and accuracy in reportage remain ever more important. The three exile media professionals interviewed here have proven themselves to be individuals with professional integrity, a life-long commitment to media freedoms, democratization, non-racial or ethnic discrimination and defence of basic human rights including the freedom of expression. Expressly, their brand of journalism is tied to Myanmar people’s struggle for a democratic government which will promote and defend press freedoms as part of the Universal Human Rights. They strive to be balanced and objective in their professional work. But they do not shy away from stating their democratic bias: they all state openly their journalism is grounded in a set of democratic, and pro-human rights values. As such, Myanmar exile media professionals would welcome opportunities to collaborate with other like-minded exile media communities from countries under repressive regimes. Additionally, they would welcome financial support from global organizations that are dedicated to promoting media freedoms and development of independent and high quality media organizations.