Authors of the report

- Azerbaijan: Khaled Aghaly

Lawyer and specialist in media law in Azerbaijan. Aghaly has been working in the field of media law in Azerbaijan since 2002. He is one of the founders of the Media Rights Institute (MRİ Azerbaijan). The Media Rights Institute was forced to suspend its activities in 2014. Since then, Agaliev has been working individually. He is the author of more than 10 reports and studies on the state of media rights in Azerbaijan.

Major priority of International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech “Adil Soz” is establishment of open civil society over the statement in daily life of the country free, objective and progressive journalism. The main activity of the Foundation is monitoring of violations of freedom of speech, legal activity, educational activity and legal help to journalists and mass media.

School of Peacemaking and Media Technology is a nonprofit media development organization encouraging freedom of expression, diversity, researches and training on media issues based in Bishkek.

- Tajikistan: Partner, who preferred to stay anonymous

- Turkmenistan: Ruslan Myatiev, Turkmen.news

Turkmen journalist, human rights activist, and editor of the news and human rights website Turkmen.news – one of the few independent sources covering Turkmenistan. The website is based in the Netherlands, where it was set up in 2010.

Myatiev frequently writes and broadcasts for the media and speaks at various international conferences and seminars as a Turkmen expert on socio-economic subjects, on politics and human rights.

- Uzbekistan: Sergei Naumov

Freelance journalist for major media outlets – Fergana.ru (Russia) and IWPR (UK). From 2008 to 2017 he authored several reports for international organisations and regional online forums on the state of freedom of speech, expression and the press in Uzbekistan. He is an active participant in the country’s activist movement. From 2007 to the present day he has been monitoring the use of child labour on cotton plantations, creating human rights content, and participating in the research projects of European human rights organisations. Naumov has been a volunteer at the School of Peacekeeping and Media Technology in Central Asia (Kyrgyzstan) since 2014.

- Photographers

Madina Alihmanova (Kazakhstan), Meydan TV (Azerbaijan), kaktus.media (Kyrgyzstan), Nozim Kalandarov (Tajikistan), turkmen.news (Turkmenistan) and Sergey Naumov (Uzbekistan).

INTRODUCTION

This report forms part of an extensive study on attacks against journalists, bloggers, and media workers covering 12 post-Soviet countries. This section of the study is devoted to Azerbaijan and the five Central Asian countries: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

The research is being conducted by the Justice for Journalists Foundation in conjunction with partners from the indicated countries.

METHODOLOGY

The data for the study have been obtained from open sources in the Russian, English, and official state languages using the method of content analysis. Lists of the main sources are presented in Annexes 2 — 7. Besides that, in the countries in which information is the most difficult to obtain due to their closed nature – Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan — material that has previously not been made public and was obtained using the expert interview method was likewise used for the analysis. Expert interviews with journalists and their lawyers were likewise used in compiling the report on Azerbaijan.

Based on further analysis of 1,464 instances of assaults on professional and citizen journalists, bloggers and, other media workers, three main types of attack were identified:

- Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health

- Non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats

- Attacks via judicial or economic means

Each of the types of attacks presented is further divided into sub-categories, a complete list of which is presented in Annex 1.

PRINCIPAL TRENDS

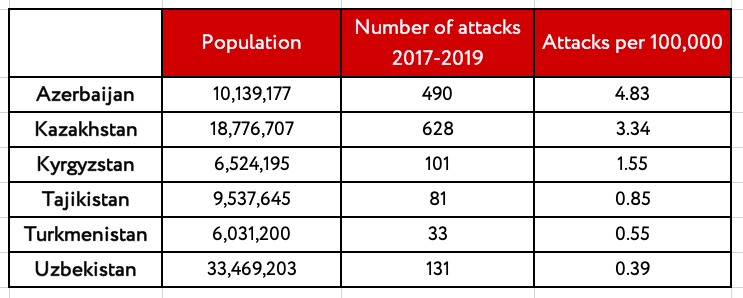

The population of the region in the period covered in this study numbers almost 84.5 million people, approximately equal to the population of such countries as Germany, Iran, or Turkey. In order to make a valid comparison of the number of incidents in these countries, it would be advisable to look at not the absolute numbers of attacks, but at the relative figures, per 100 thousand people.

As paradoxical as this may seem, the high indicators for the numbers of attacks in countries such as Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan speak not so much to the brutality of the environment in which media workers are forced to work as to the relative freedom of speech in these countries. Thus, in Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan — where according to the available data media workers are hardly ever subjected to attacks — such incidents simply do not receive any publicity by virtue of a practically complete information vacuum.

In Turkmenistan – the most closed of these countries in the informational regard (in 2019 it held last place, 180th, in the Reporters Without Borders NGO’s annual rankings) — it is practically impossible to work as a journalist. Information about what is happening in the country is reported to media beyond the border by “people’s correspondents”. They send photos and videos at the risk of being caught by the high-cost national tracking system that embraces the entire country. The relevant section of this study should give some idea of the dangers faced by those people who are still trying to get the truth about what is happening in Turkmenistan to the world.

All six countries except Uzbekistan show an increase in the absolute number of attacks in 2019 as compared with 2017. Attacks via judicial means (above all short-term detentions, arrests, and the opening of administrative and criminal cases) predominate in the region covered in this study. The main source of threats for media workers are representatives of the authorities. The number of attacks of this type has increased over three years in four of the countries, but it declined in Kyrgyzstan and remained largely constant in Uzbekistan.

Azerbaijan leads by a wide margin in terms of the number of physical attacks – 26 such incidents became known just last year alone. Brutal beatings of journalists during short-term detentions and even abductions of journalists with subsequent removal from other countries are characteristic of this country.

Kazakhstan ranks first in attacks via judicial and/or economic means. On average, more than 50 cases are initiated inKazakhstan each year against media workers on charges of libel, insult, and reputational damage. 30-40 incidents per year reach trial; a fine is awarded in half of the instances, while a third result in a prison term. Non-physical attacks are likewise widespread in Kazakhstan, including harassment, intimidation, damage to/seizure of property and documents, and breaking into equipment and online accounts.

Tajikistan leads the region in the number of media workers charged with extremism, links with terrorists, and inciting hate. Persecution of family members of journalists, their harassment, interrogations, short-term detentions, and even arrests are likewise characteristic of Tajikistan.

The character of attacks perpetrated against journalists in Kyrgyzstan has shifted towards a manifold increase in online threats, via DDoS and hacker attacks on online media outlets.

THE RELEVANCE OF THIS STUDY

Despite the relative informational isolation of the Central Asian countries, the global community should not ignore what is happening in this region.

Taking advantage of the language barrier, geographical remoteness, and low degree of integration of these states into global political and informational agendas in pursuit of their own interests, their authoritarian rulers can “test” various methods of pressure on journalists with impunity – methods which are then gradually exported to other countries. Thus, accusing journalists of extremism and links with terrorists, as well as the criminalisation of laws on spreading libel and violation of privacy, are widely used in Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan to force corruption investigators and opposition journalists and bloggers to keep silent.

In conditions of an absence of a democratic separation of powers, no police accountability, and the dependence of the judiciary on the executive, professional and citizen journalists cannot count on receiving protection and justice in their countries. The only thing that can ease their fortunes and enable them to continue working and bringing the truth to broad audiences is the attention of the international community.

The Justice for Journalists Foundation, together with its partners and experts, carries out weekly monitoring of attacks against media workers in all post-Soviet countries excluding the Baltic states, the results of which are published on the JFJ Media Risk Map in both Russian and English.

On March, 25 Index on Censorship and Justice for Journalists Foundation announced a joint global initiative to monitor attacks and violations against the media, specific to the current coronavirus-related crisis. Media freedom violations will be catalogued with a map hosted on Index’s current website.

Azerbaijan

1/ KEY FINDINGS

490 instances of attacks/threats against professional and citizen media workers and the editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Azerbaijan were identified and analysed during the course of the study. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Azerbaijani, and English languages using the method of content analysis. Personal communications from journalists who had been subjected to assaults and their lawyers were likewise used. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 2.

- Abduction and pre-trial deprivation of liberty of media workers are a widespread practice in Azerbaijan. Whilst in custody, journalists are regularly subjected to beatings and torture.

- The main type of attacks on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in Azerbaijan is attacks via judicial and/or economic means.

- The main methods of applying pressure on journalists are short-term detentions, accusations of libel, insult, and reputational damage, court trials, and the closure of media outlets or blocking of an online resource on the internet.

- The main method of non-physical pressure on media workers is cyber-attacks, which, as a rule, are followed by the official closure of the internet site.

- Azerbaijan is one of the countries where the relatives of opposition-minded media workers are subjected to pressure, threats, and arrests.

2/ THE MEDIA IN AZERBAIJAN

There are 12 national television channels with country-wide coverage operating in Azerbaijan. Three of them – AzTV, İdman Azərbaycan [Sports Azerbaijan] and Mədəniyyət [Culture] – are owned by the state and receive all their funding from it. Public television is likewise financed from the state budget.

The remaining eight republic-wide broadcasters (ATV, SPACE TV, XƏZƏR TV, LIDER TV, ARB, CBC Sport, REAL TV, and ARB 24) are privately owned. However, the actual identity of most of their owners is unknown, and information about their ownership structure is undisclosed. According to independent experts, these channels belong to or are controlled by individuals associated with the government.

12 broadcasters transmitting regionally (ARB Ulduz, ARB Kəpəz, DÜNYA TV, QAFQAZ TV, ARB Günəş, ARB Cənub, MİNGƏÇEVİR TV, ARB Şəki, ARB Aran, ARB Şimal, Naxçıvan TV, and KANAL 35) belong de jure to private owners. But in fact, the regional broadcasters likewise belong to or are controlled by persons associated with the government.

There are 13 radio stations with country-wide coverage operating in Azerbaijan (Respublikanskoye Radio, Obshchestvennoye Radio, radio Azad Azərbaycan, the independent television and radio company Antenn, radio 100.5 FM, radio 106 FM, radio Jazz FM, radio Space 104 FM, radio Xəzər, radio Media FM, radio ARAZ FM, Avto FM, and radio ASAN). The NAR State Committee for Television and Radio and radio Golos Nakhchyvana [Voice of Nakhchivan] broadcast in the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic. 10 radio stations are owned by private broadcasters. The majority of the private radio broadcasters are subsidiary structures of national broadcasters located in Baku and transmit on an FM frequency. With the exception of the city of Ganja [Gəncə], where one regional radio channel (Kəpəz FM) is broadcasting, none of the regions have local radio.

There is no precise official data on the number of news agencies, newspapers, and magazines in Azerbaijan. According to data from state agencies and journalistic organisations, there are fewer than 50 news agencies in the country. According to the same sources, the number of news websites and analytical internet resources varies, with an upper figure of 250. At least 30 daily newspapers are published and distributed in Azerbaijan, with an additional 30 or so weekly and monthly newspapers and magazines coming out.

Around 50 journalistic organisations have undergone state registration in Azerbaijan. However, the activities of most of them are nominal. Many media structures were forced to cease their activities after 2014-2015.

Azerbaijan was ranked in 166th place in the Reporters Without Borders NGO’s annual World Press Freedom Index for 2019. The situation with freedom of the press in the country had deteriorated in a year: Azerbaijan had held 163rd place in the rating in 2018.

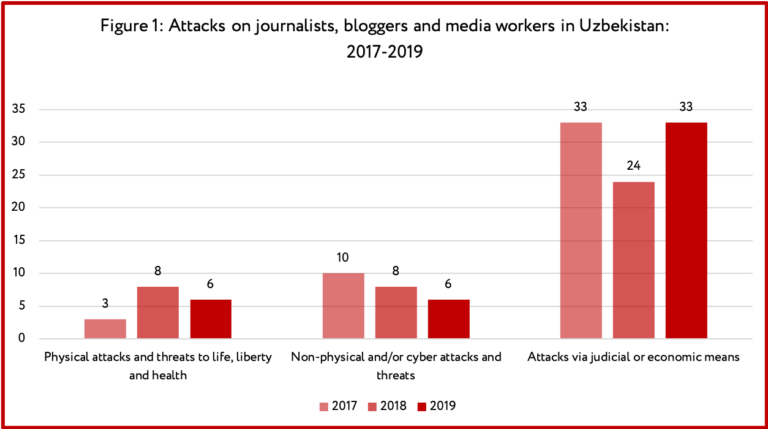

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

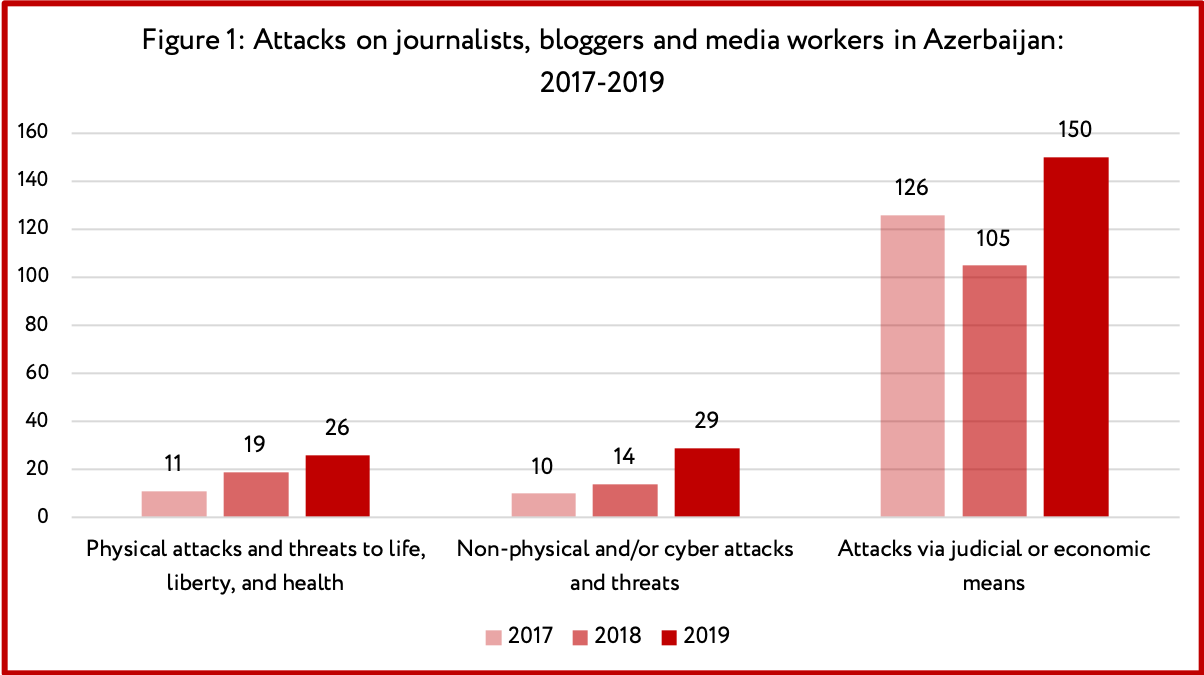

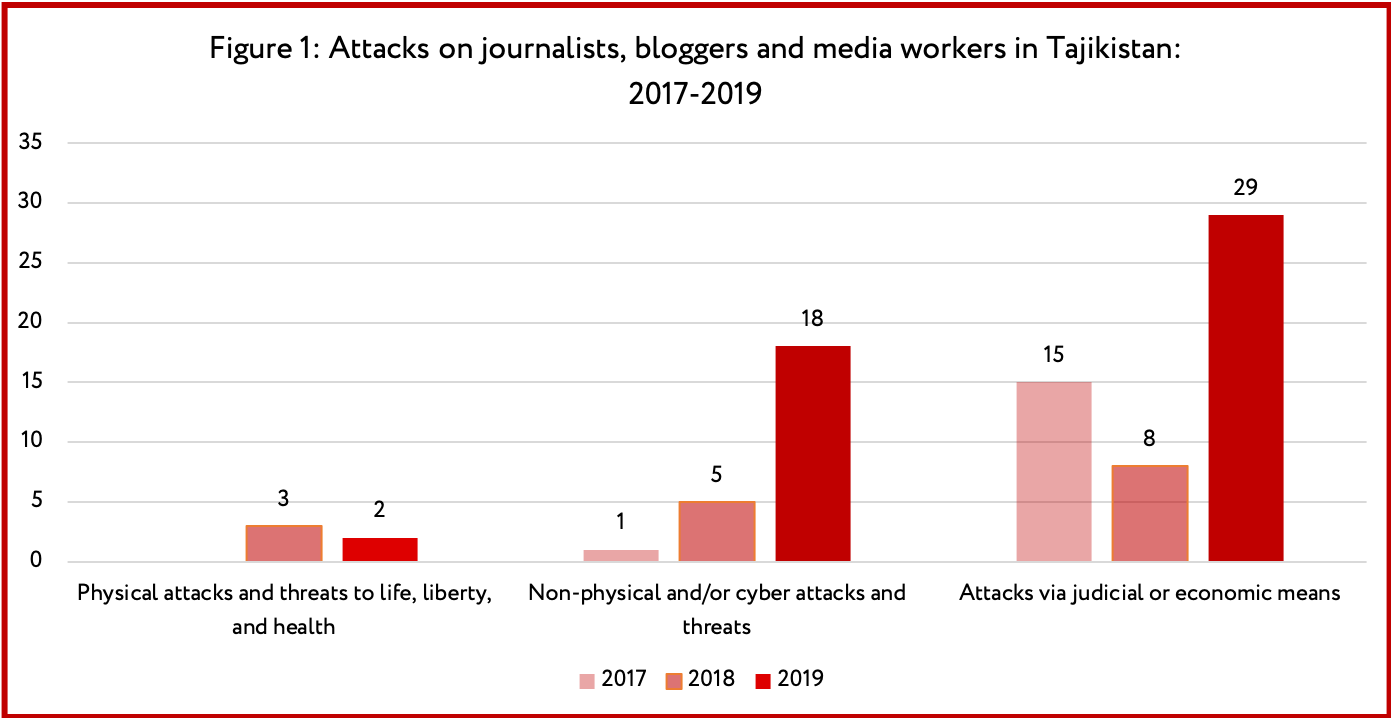

Figure 1 presents the total number of attacks on journalists, bloggers, and other media workers in Azerbaijan from January 2017 through December 2019. The number of attacks has increased in all categories since 2017. At the same time, attacks via judicial and/or economic means remain the method of choice for the authorities: most often, media workers were subjected to short-term detention by the police, as well to charges of libel, insult, and reputational damage. The number of attacks in this category increased from 125 incidents in 2017 to 150 in 2019.

It is noteworthy that judicial means of pressure are used as well in relation to the relatives and loved ones of bloggers who had been forced to flee Azerbaijan.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

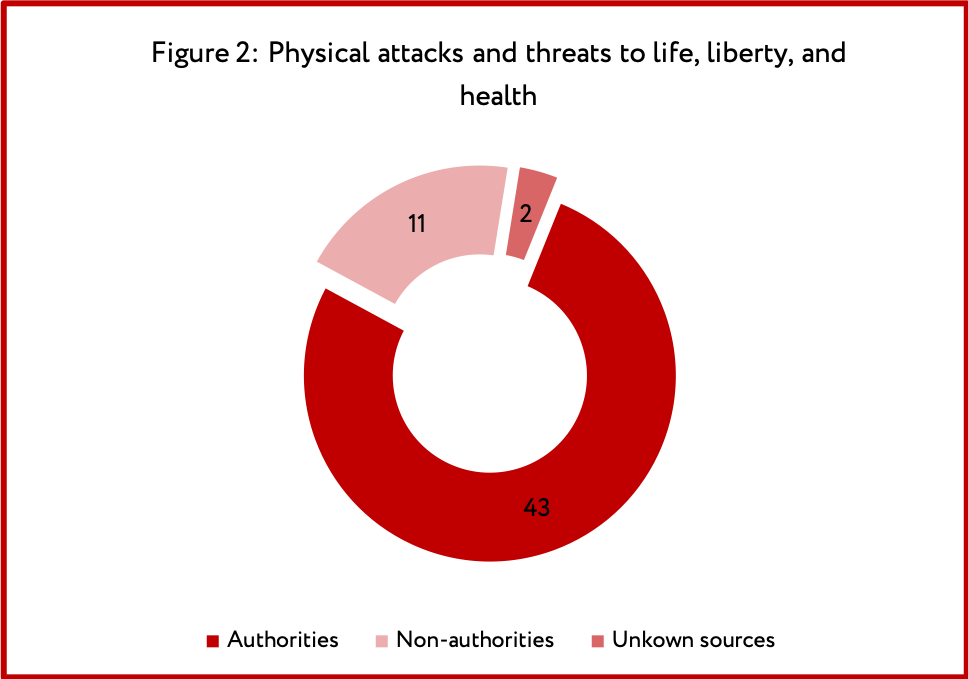

The number of physical attacks against Azerbaijani media workers increased two and a half times in the three-year study period.

Over the three years, journalists and bloggers were subjected to non-fatal attacks and beatings 47 times. Most of those who were subjected to such assaults were harsh critics of the government. In the majority of the incidents, journalists were assaulted whilst carrying out their professional activities. In several cases, journalists were subjected to assaults for their articles and for videos they had shot.

- In 2017, the political activist and blogger Mehman Galandarov who had been residing a long time in Georgia, was arrested immediately upon arrival in Baku and then died in a pre-trial detention centre.According to the official story, Galandarov hanged himself. The body was secretly buried without the proper examination procedure, relatives and the public only being informed after the fact.

- Ülvi Həsənli, editor of the opposition news website abzas.net, was illegally conscripted into military service, despite having previously been declared unfit for military service. This occurred shortly after he had organised a public hearing on the topic of the socio-political situation in Azerbaijan on 15 October 2017.

- On April 10, 2018, Famil Farhadoğlu’, a staff member at the Unikal.org news website, was subjected to an assault whilst trying to photograph the Minister of Health at a ceremony in which the latter was taking part. The journalist was beaten up and his equipment damaged. The results of an investigation into the journalist’s complaint concerning the assault were not made public.

- On April 23, 2019, the journalist Jalya Aliyeva was beaten while filming next to the Oskar hotel in a Baku suburb. The assault left her with a cranio-cerebral injury.

- On June 3, 2019, Kanal-13 internet television employee Nurlan Gahramanli was subjected to an assault whilst preparing a report in the Baku bus station complex. The security guards of the complex brutally beat up the journalist.

Over the period from 2017 through 2019, no fewer than seven journalists were abducted or illegally deprived of liberty, and some subjected to torture in custody.

- The blogger Mehman Huseynov, who had conducted investigations in relation to the property of state officials and was famed for his video broadcasts, was abducted in January 2017. There was no contact with him for over 24 hours, after which it became known that he was being held and tortured by the police. In December 2019, Huseynov was once again detained short-term and held incommunicado by the police. In his own words, policemen had driven him off to the outskirts of Baku and beaten him up.

- In May 2017, the journalist Nicat Amiraslanov was detained short-term and held incommunicado. As his lawyer later stated, the journalist was charged with resisting the police, for which a court sentenced him to thirty days’ administrative arrest. During this time, he was repeatedly subjected to torture and beatings, losing most of his teeth.

- At the end of May 2017, the independent journalist and political activist Afgan Mukhtarli was forcibly transported from his temporary residence in Georgia into Azerbaijan. There, he was promptly arrested and charged with illegal border crossing, smuggling, and resisting a law enforcement agency operation. Mukhtarli denied these charges: he stated that on the evening of May 29 he had been abducted in Tbilisi and transported to Azerbaijan territory, where money that did not belong to him was planted on his person and he was beaten. The court found him guilty and sentenced him to six years of deprivation of liberty.

- In March 2018, the blogger Fatima Movlami was detained for five days at the Ministry of Internal Affairs Main Administration for Fighting Organised Crime. Movlami had been one of the participants in the “We’ll Show You A Dictator” demonstration directed against the president of Azerbaijan. During this whole time, her relatives did not have any information as to her whereabouts.

- An employee of the internet television channel Kanal-13, Ismail Islamoglu, known for his critical articles about the Heat music festival in Baku, spent three days at the Main Police Administration without any communication with the outside world. During his time of detention he was left for hours without food, water, or the ability to sit or lie down, as well as being subjected to beatings, insults and, threats.

- In 2018, the journalist Aytaj Ahmadova, working with Meydan TV, which transmits out of Germany, was detained short-term whilst preparing material about a protest action. She was forcibly brought to a police station and held there. The journalist was unable to get an investigation opened into the matter of the violence on the part of the police.

In most cases, the law enforcement agencies were notified of incidents of physical attacks against journalists, but the attackers were rarely held accountable or the results of investigative proceedings were not disclosed.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER ATTACKS AND THREATS

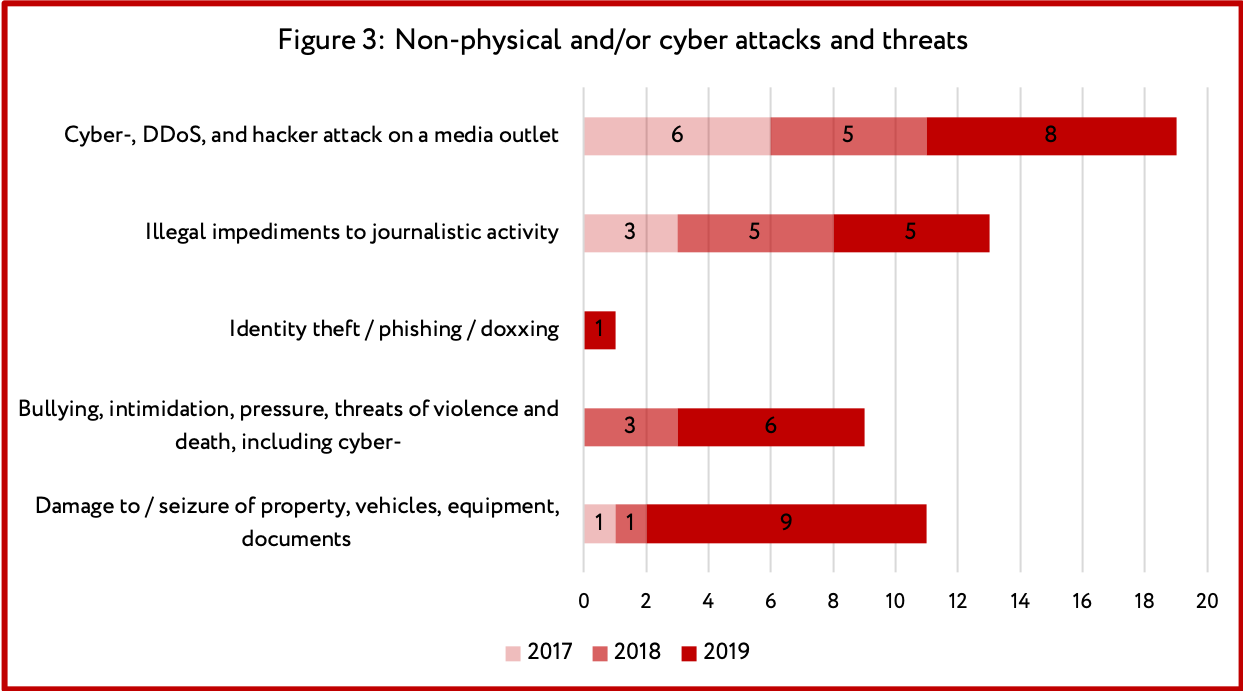

The principal method of non-physical attacks in Azerbaijan is cyber-attacks (including DDoS and break-in attempts) in relation to internet media. The second most widespread method of applying pressure is illegally impeding journalistic work, that is prohibiting filming and gathering information for articles and television features.

Independent internet media that criticise the government are regularly subjected to cyber-attacks. At least 19 such attacks were recorded in the three years. As a result, access to these resources is cut off for a long time; a number of websites had their databases deleted. Most of the online media outlets that lived through such attacks were shut down afterwards anyway, be it with a court decree or extrajudicially.

- The opposition websites abzas.net, cumhuriyyet.net, and azadliq.info were repeatedly subjected to attacks, in the course of which they became inaccessible. In May 2017, the opposition website 24saat.org was subjected to an attack and was later blocked to visitors inside the country. According to data from VirtualRoad.org, it is highly likely that the obstruction of the work of opposition websites was carried out at the instruction of state agencies.

- In 2018, the State Security Service arrested Ikram Rahimov, editor of the website realliq.info. Following his arrest, this website and five others that he headed were blocked without a court decree.

- In 2019, the following websites were blocked extrajudicially: kanal13.tv, gununsesi.org, gununsesi.info, gununsesi.az, nia.az, neytral.az, politika.az, vediinfo.az, obyektiv.org, sonolay.org, ulus.az, qanunxeber.az, xalqinsesi.com, aztoday.az, euroasianews.org, avropanınsesi.org, euroasianews.blog, euroasiainfo.com, infoaz.org, realliq.info, realliq.az, realliqinfo.org, realinfo.az, realliqinfo.com, realliqinfo.az, abzas.net, cumhuriyyet.net, and xeber-xetti.az.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL OR ECONOMIC MEANS

The main methods of attacks and threats via judicial and/or economic means are: short-term detention, accusations of libel, insult, and reputational damage, court trials, shutting down a media outlet or blocking an internet site, and interrogations.

In Azerbaijan, as in Tajikistan, extensive use is made of interrogations, short-term detentions, and arrests of the relatives and loved ones of independent journalists and bloggers who have been forced to leave Azerbaijan, with at least seven such incidents having been identified.

- In February 2017, a court kept under arrest the brother and nephew of the blogger Ordukhan Temirkhan, who had earlier been forced to emigrate to the Netherlands. Two of his nephews and another loved one were sentenced to administrative arrest in 2018.

- The father of the blogger Mahammad Mirzali, who had emigrated to France, was detained short-term in January 2018. The policemen demanded that his son remove critical posts from social networks or else they would arrest other relatives of the blogger as well.

- In February 2018, the father of the blogger and activist Tural Sadigly, who lives in Germany, was detained short-term. His brother was also detained short-term and sentenced to administrative arrest in 2018.

- In June 2018, relatives of Rafiq Dzhalilov, editor-in-chief of the newspaper Golos Talysha, were subjected to interrogations. His brother was later detained short-term.

During the period being analysed, journalists and media workers encountered pressure on the part of official persons and state structures 241 times. Usually, the journalists are detained short-term and taken to a police station whilst carrying out professional duties —covering anti-government demonstrations as a rule. Thus, at least 21 such incidents were recorded in 2018. The police detained the journalists short-term despite the press credentials they were carrying, and released them only after the protest action had ended.

7/ SHUTTING DOWN A MEDIA OUTLET/BLOCKING AN INTERNET SITE

A law On Informatisation was adopted in early 2017 which enables the blocking of any internet site at the request of the Ministry of Communications. By May 2017, five of the main independent websites in Azerbaijan had been blocked. Besides that, access to dozens of websites not associated with the government was restricted without court decrees. Internet publications were being subjected to shutdown and blocking 58 times over the course of 3 years.

- On May 12, 2017, the Ministry of Communications filed a lawsuit requesting the blocking of five of Azerbaijan’s critically minded Azeri internet websites. The Ministry was asserting that unlawful content was being disseminated on the websites of Radio Azadliq, the newspaper Azadliq, the Azərbaycan saatı programme, Meydan TV, and the internet television channel Turan. What was being referred to was articles with harsh criticism of the government on the part of opposition politicians. The local courts ruled in favour of the Ministry, and access to the websites was blocked. Higher-standing courts dismissed the appeals against this ruling. The complaint is currently being examined by the European Court of Human Rights.

- Realliq.info, which had been criticising the government’s media policy, was blocked in November 2018 without a court decree. The website’s team created the website realliq.az, which was likewise blocked in December 2019 without a court decree. Realliqinfo.com, Realliqinfo.az, and Realliqinfo.org were blocked in an analogous manner.

- The independent internet television website Kanal-13 was blocked in December 2017 without a court decree.

8/ CRIMINAL CHARGES, COURT TRIALS, AND ARRESTS

Over the span of three years, journalists, bloggers, media workers, and media editorial staffs were charged 72 times with libel, insult, and reputational damage, seven times of extremism, links with terrorists, and calls to incite hate, and17 times with extortion, tax evasion, illegal possession and sale of narcotics, hooliganism, and illegal border crossing. In three years, there were 56 court trials, although not all of the criminal cases that were opened ended up going to trial. Claims were filed in court against the media by state officials, government agencies, and businessmen close to the government.

During the period covered in this study, 27 incidents were recorded in the sub-category of “administrative arrest/remand/pre-trial detention/prison” of media workers on various charges. In 19 of these cases, journalists had been sent to a pre-trial temporary detention “isolator” before a court decision on arrest. In two cases, journalists were convicted of libel and insult. In the other cases, the verdicts were issued under Criminal Code articles on extortion, hooliganism, anti-state appeals [i.e. calls to commit treason], high treason, possession of narcotics, and illegal border crossing. The journalists, their lawyers, and local human rights organisations have stated that the arrests were directly related to the professional activities of the journalists.

In 2019, chief of the bastainfo.com website Mustafa Gadjibeili, editor-in-chief of the criminal.az website Anar Mammadov, and editor of the teref.info website Nuraddin Ismailov were criminally prosecuted for “openly calling for the violent seizure of power, or the forcible retention thereof, or a violent change of the constitutional order, or a violent violation of territorial integrity and distribution of materials with such content”. All three journalists were given suspended sentences of 5 years 6 months.

Kazakhstan

1/ KEY FINDINGS

628 instances of attacks/threats against professional and civilian media workers and the editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Kazakhstan were identified and analysed during the course of the study. The data for the study were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Kazakh, and English languages using the method of content analysis. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 3.

- The main type of attacks against traditional and digital media workers, as well as bloggers, in Kazakhstan are attacks via judicial and/or economic means.

- The main source of threats for media workers in Kazakhstan are representatives of the authorities, primarily using such methods as short-term detentions, accusations of libel, and prosecution in the courts.

- Mass short-term detentions are directly associated with the rise in protest sentiments in society. Short-term detentions of journalists take place as they are covering mass demonstrations in Kazakhstan’s large cities.

- The second main type of attacks against traditional media journalists and civilian journalists, according to data from open sources, are non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats.

- In the space of three years the number of physical attacks against journalists has almost tripled; the vast majority of these consist of non-fatal beatings.

2/ THE MEDIA IN KAZAKHSTAN

According to the data of the Ministry of Information and Social Development, the number of officially registered domestic media outlets in 2019 decreased in comparison with 2018 from 3,328 to 3,185.

Of the 3,185 media outlets, 2,951 consist of print and internet media outlets and news agencies (compared with 3,130 in 2018), 161 are television channels (128 in 2018), and 73 are radio channels (70 in 2018).

Based on the data of the annual World Press Freedom Index rating of freedom of speech drawn up by the Reporters Without Borders NGO, Kazakhstan took 158th place out of 180 in 2019. The country had fallen one place in a year.

In the 2018 Freedom on the Net rating by the Freedom House international human rights organisation, Kazakhstan ranked 46th out of 65 for level of freedom on the net, falling into the category of countries with an unfree internet. In 2019, Freedom House placed Kazakhstan among 33 states (out of the 65 analysed) where the situation regarding internet freedom had worsened over the past year. Freedom House included Kazakhstan in its list of countries where “the internet, social networks, and communications platforms are often blocked”, “political, social, or religious content is restricted”, and “bloggers, human rights advocates, network users, or persons criticising the authorities are subject to persecutions and prosecuted.”

The effect of the transition of power on the state of the media

The main socio-political factor to have affected the situation with freedom of speech in Kazakhstan in 2019 became the rather peculiar transition of power. On March 19, 2019, Nursultan Nazarbayev resigned as president of Kazakhstan, a post he had held since 1991. Speaker of the Senate Kassym-Jomart Tokayev became the acting president of the country. On June 9, 2019, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev became President of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Nursultan Nazarbayev remained chairman of the Security Council of Kazakhstan for life. The Security Council is a constitutional body that coordinates the implementation of a unified state policy in the sphere of ensuring national security and the defence capability of the Republic of Kazakhstan in order to maintain internal political stability and defend the constitutional order and the state independence, territorial integrity, and national interests of Kazakhstan on the world stage. All appointments to key offices of state are approved by the Chairman of the Security Council. Nursultan Nazarbayev remained the leader of the Nur Otan political party.

The changes in the regime prompted an unprecedented surge in civic activism. March, May, June, and July saw large-scale unsanctioned peaceful rallies taking place in the country. The activation of public life intensified the polarisation of the media. Most publications receiving financial support from the state avoided coverage of sensitive topics. The journalists of independent publications covering the rallies were subjected to short-term detentions and assaults. A significant increase in activity was noted among users of social networks.

The highest state bodies of power are continuing their efforts to maintain and increase control over the media. However, they are forced to reckon with pressure from the international community. As a result, the harsh repressions against the media seen in the first half of the year softened somewhat in the second half.

Legislative regulation of the activities of the media and journalists

From 2017 to 2019, several legislative acts are being applied in Kazakhstan that significantly restrict the exercise of constitutional guarantees of freedom to obtain and disseminate information.

A number of changes to laws on questions of information adopted in 2017 are significantly at odds with international standards on freedom of speech: additional mechanisms for monitoring commentators on social networks and other internet resources were introduced; the procedures for furnishing information were made more complicated and the time period for furnishing information in response to requests from journalists was increased by two and a half times; the concept of “propaganda” was introduced which virtually prohibits publication in the media of information prohibited by Kazakhstan legislation; and an obligation was imposed on journalists to obtain consent for the dissemination of personal and family secrets, even though these concepts lack a precise legal definition.

In 2018, the authorities announced that work had begun on developing an information system called Automated Monitoring of the National Information Space, the principal aim of which is more efficient state monitoring of the media in order to identify materials that violate the legislation of the RK (terrorist, extremist, and suicide propaganda and the dissemination of knowingly false information). In this same year, the government approved a list of several state organisations that have the right to priority use, as well as suspension of the activity, of networks and means of communications during a threat or in the event of a social, natural, and technological emergency, as well as to declare a state of emergency.

These are the Prosecutor General’s Office, the National Security Committee, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the Ministry of Defence.

Several initiatives by the authorities to liberalise legislation should be noted as well. These are the decision to decriminalise libel and the proposal to exempt periodical print media that offer an internet version of their publication from paying VAT.

3/GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

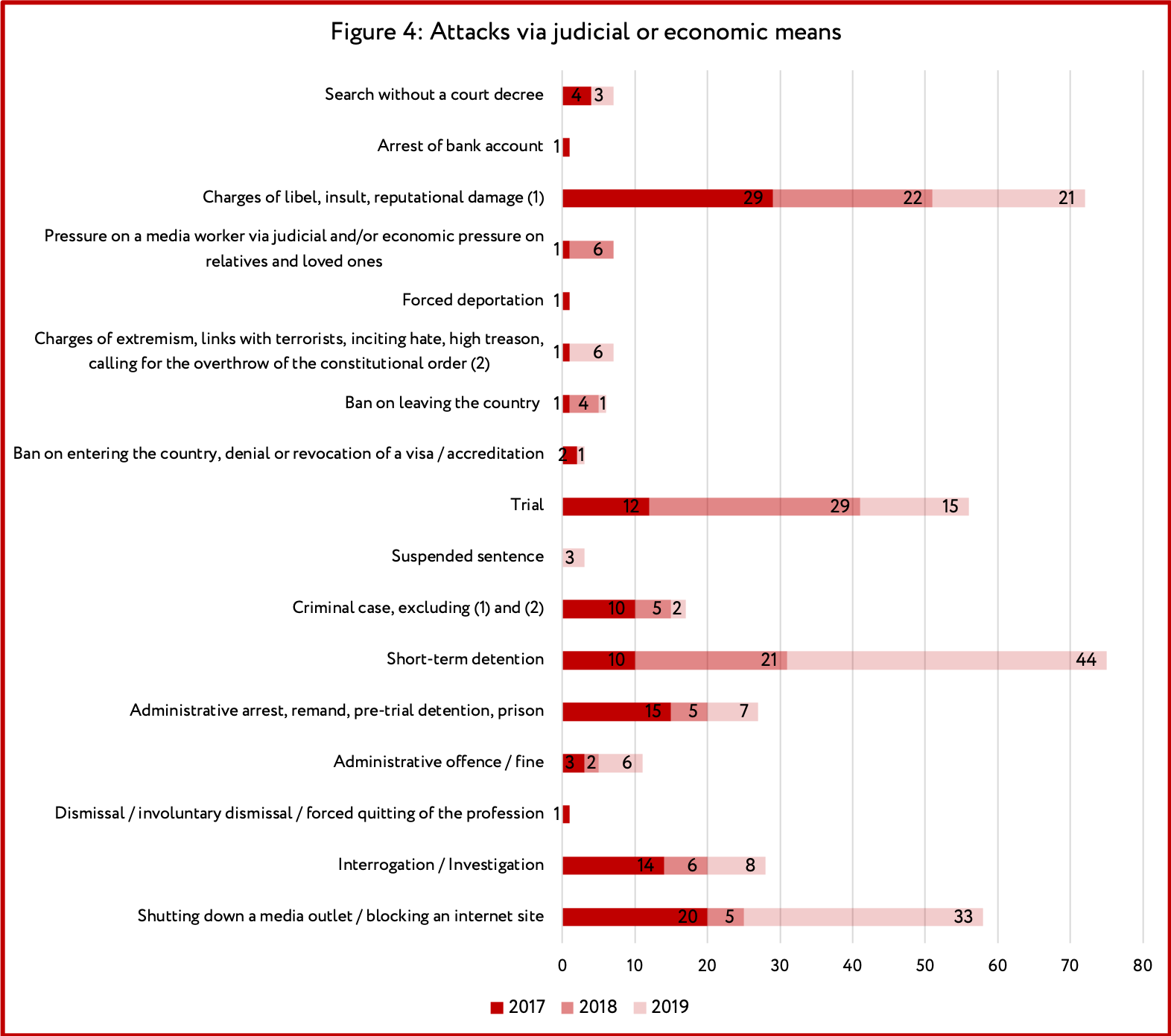

Figure 1 represents a quantitative analysis of the three main types of attacks against journalists on the territory Kazakhstan in the period from January 2017 through December 2019. The number of attacks in all three categories increased over the three years. The number of attacks via judicial and/or economic means increased 1.3 times in 2019 compared with 2017, while physical attacks and/or threats to life, liberty, and health went up 2.7 times, and non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats were up 1.4 times.

The main purpose of attacks/threats is to impede the publication of materials. Threats of physical violence were almost never carried out. This is perhaps the reason why these types of attacks are not widely covered in the media: most journalists regard them as unavoidable and presenting no real danger.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

In 2017-2019, 28 instances of physical attacks became known, including threats to the life, liberty, and health of media workers. Of these, 24 instances – the overwhelming majority – consisted of non-fatal attacks: beatings and injuries.

The only fatal incident occurred on December 27, 2019: production editor of the internet media outlet Informburo.kz Dana Kruglova died in a Bek Air aeroplane crash near the village of Kyzyl Tu in Almaty Oblast.

Kazakhstan is one of those countries that continue the Soviet tradition of using punitive medicine against dissidents and dissenters. Thus, on March 15, 2018, the blogger Ardak Ashim was detained short-term on suspicion of inciting nationality-based, religious, and social hate, while on March 27, a court decreed to commit her to a psychoneurological dispensary for one month.

- In May 2017, Yermurat Bapi, chairman of the civic foundation Journalists in Need, received a knife wound.

- In June 2019, Shokan Alkhabayev, a correspondent for the internet media outlet Tengrinews.kz, who had been covering mass short-term detentions, was brutally beaten by policemen.

- In July 2019, reporters for Radio Azattyk and other journalists suffered from a deliberate pepper spray attack from a spray canister in Nur-Sultan.

- In July 2019, an assault was perpetrated on journalists from several publications in the press hall of the Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights in Almaty, resulting in damage to or theft of professional equipment, video cameras, photo cameras, and smartphones.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

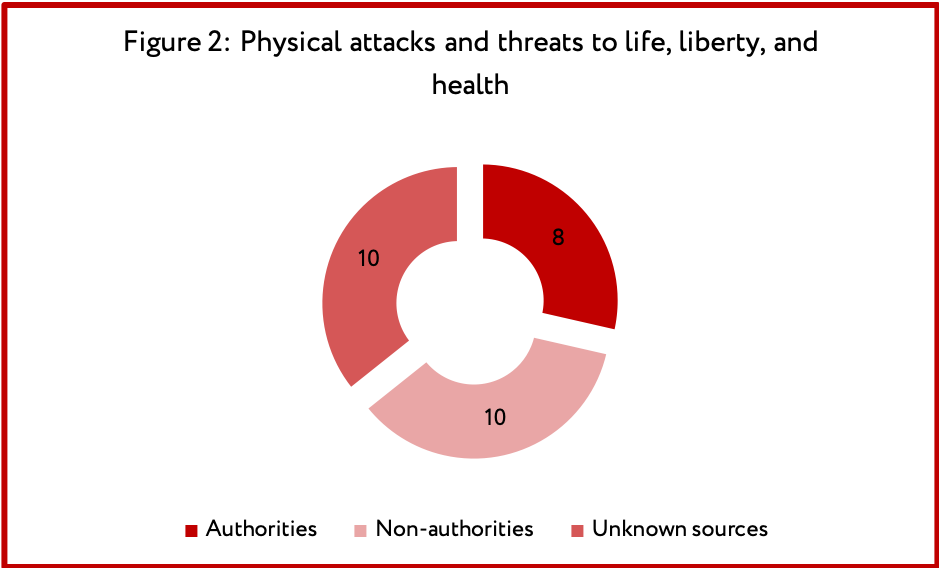

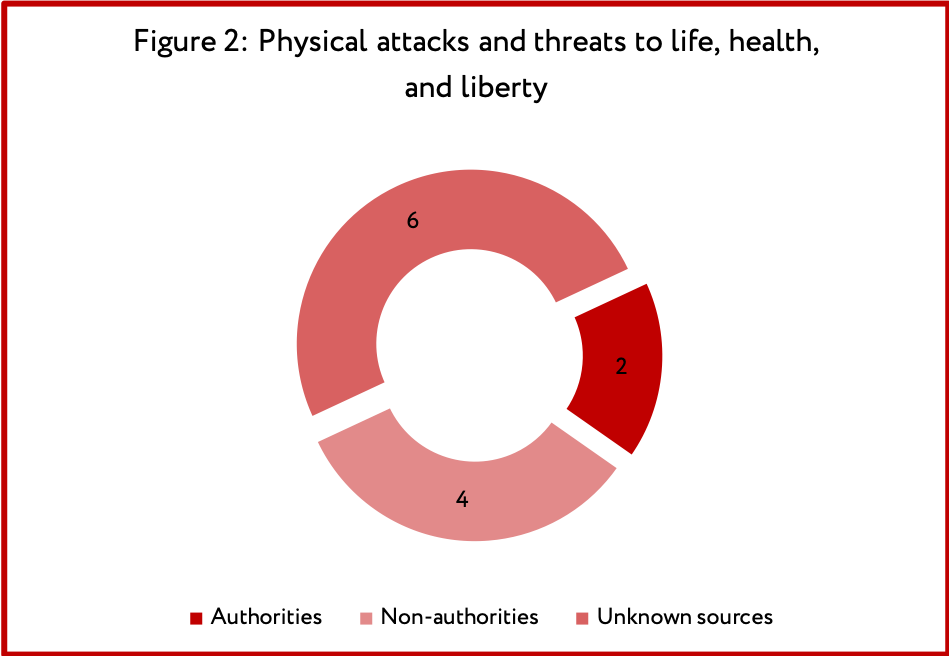

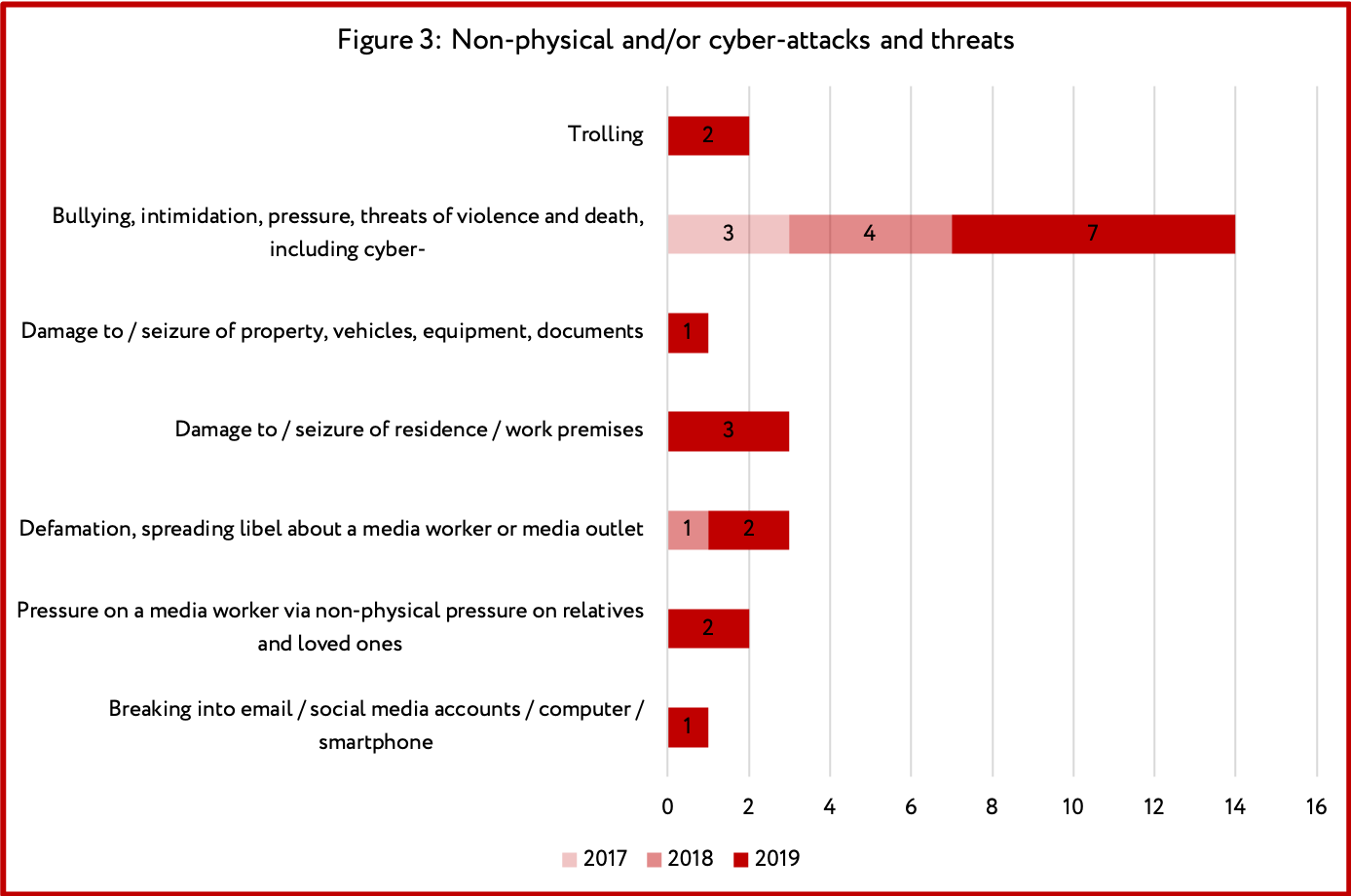

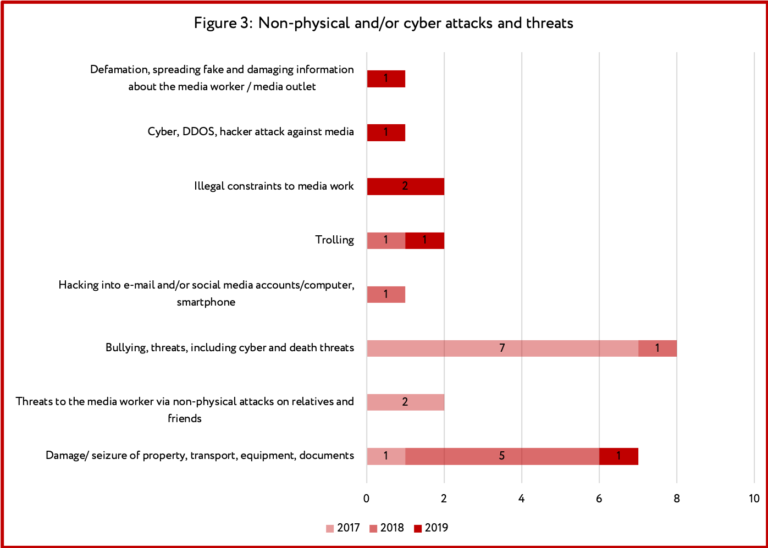

Figure 3 presents the number of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats. As can be seen, the most popular methods of non-physical pressure on media workers are harassment, intimidation, and pressure; damage to/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, and documents; breaking into e-mail and social media accounts, and illegal impediments to journalistic activity.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL OR ECONOMIC MEANS

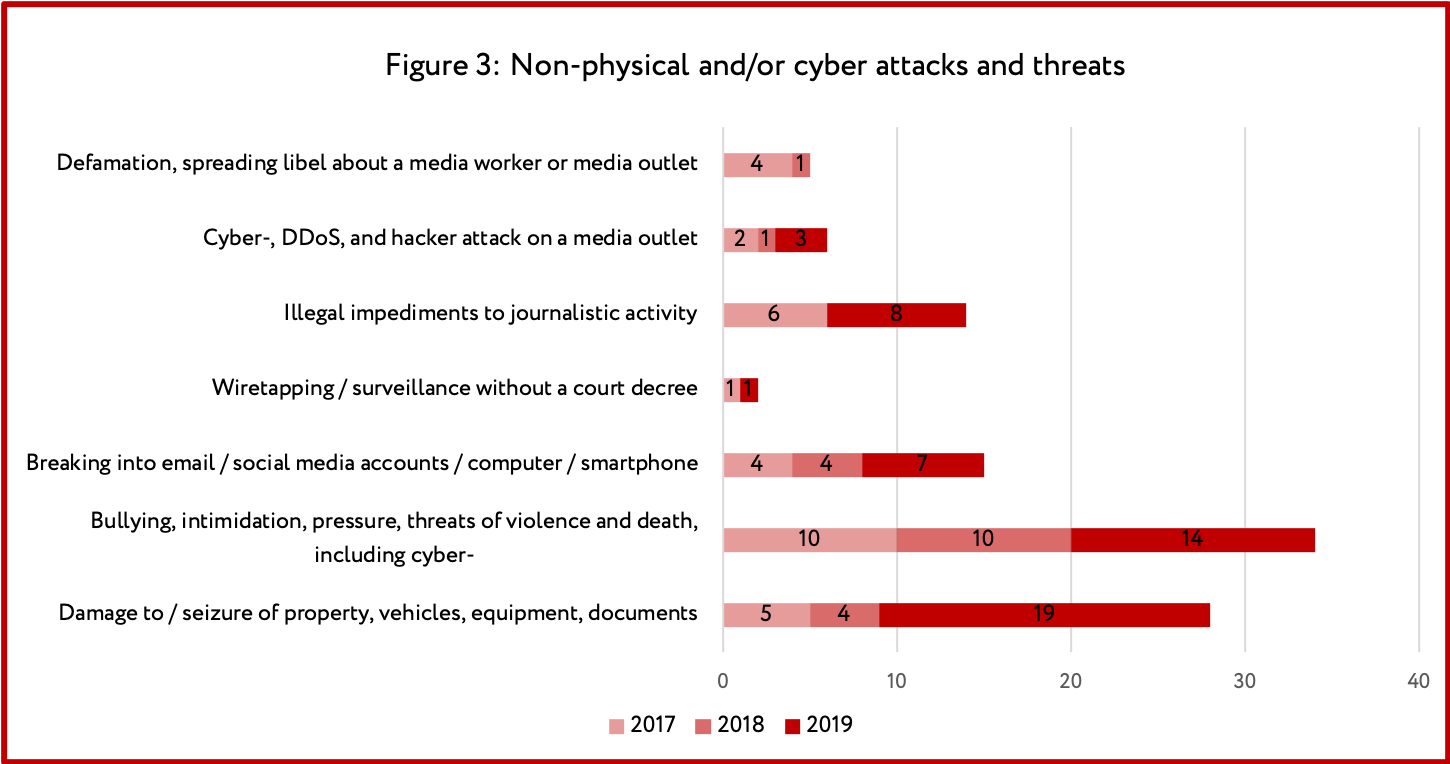

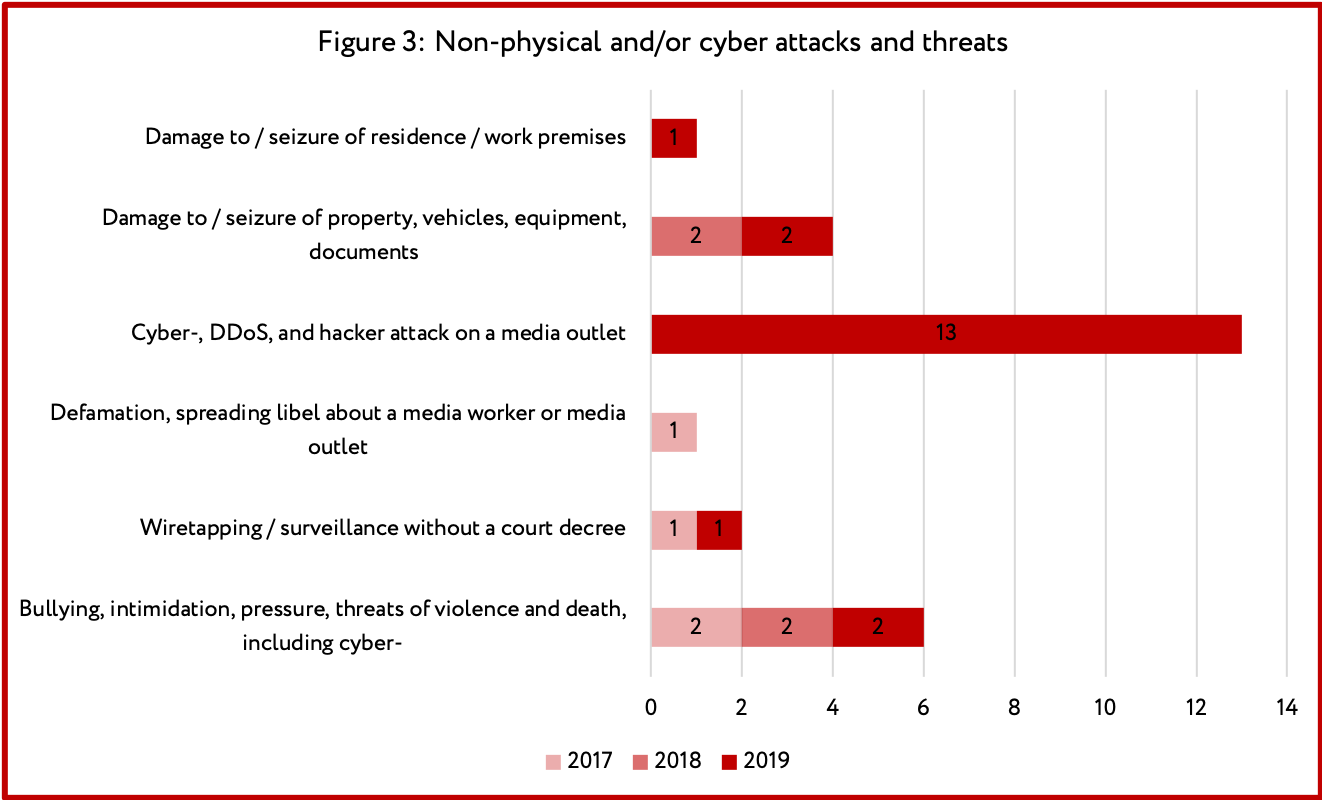

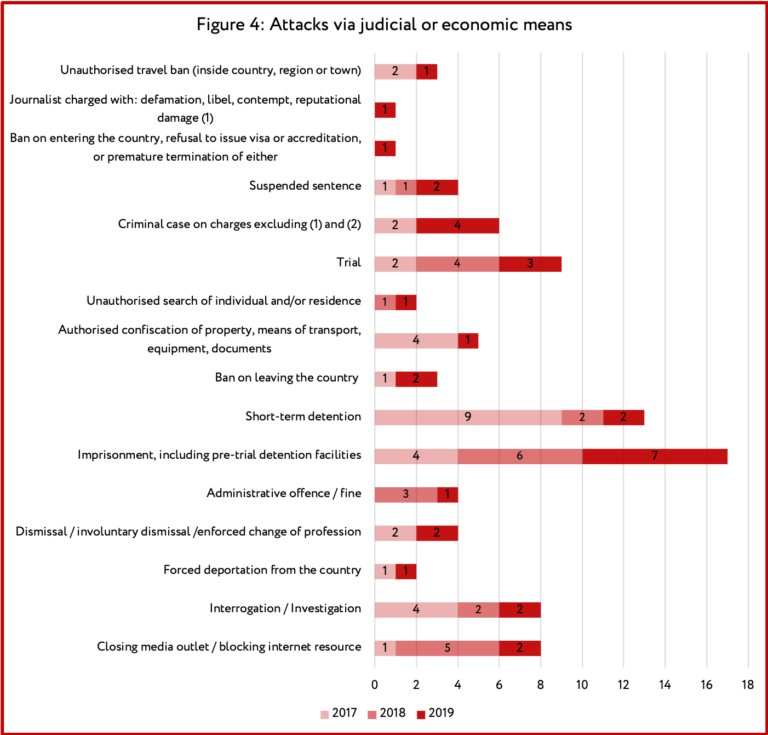

Figure 4 presents the various sub-categories of attacks via judicial and/or economic means. The top 5 methods for pressure on media workers include accusations of libel, insult, and reputational damage, court trials, short-term detentions, interrogations, and fines.

It is noteworthy that short-term detention began to be used extensively by the authorities in 2018, while in 2019 the number of such incidents increased by 2.5 times, from 14 to 34.

7/ SHORT-TERM DETENTIONS

2019 saw a significant increase in attacks against media workers on the part of the authorities. This is associated with the rise in protest sentiments in society as a result of the holding of snap presidential elections. Most of the short-term detentions took place during coverage of unsanctioned public demonstrations or as a preventive measure in order to make the participation of journalists in the coverage of rallies and other protest actions impossible. The short-term detentions were accompanied by violations of procedural norms.

The peaks of the short-term detentions occurred in June 2018 and February and June 2019.

- The short-term detention of seven journalists on June 23, 2018 in Uralsk, Almaty, and Astana. The journalists were intending to cover unsanctioned rallies “for free education” that did not actually end up taking place.

- On February 27, 2019 in Zhanaozen, Uralsk, and Almaty, four journalists were detained short-term after having arrived at offices of the Nur Otan party — the venues of anticipated rallies; one journalist was detained short-term upon leaving his home.

- On June 9, 2019, the day the snap presidential elections were announced, large-scale protest actions took place in Kazakhstan, accompanied by a large number of short-term detentions of citizens. The demonstrations continued until June 12. Whilst covering the events from June 9 through 12, 14 journalists were detained short-term in Almaty, Nur-Sultan and Uralsk.

In particular, a British journalist, Agence France-Presse Central Asia correspondent Chris Rickleton, was among the journalists who suffered. He was detained short-term on June 9 in Astana Square in Almaty whilst attempting to get an interview. The journalist was released after the intervention of the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Kazakhstan; Chris Rickleton later had his accreditation card and video equipment returned, however the police erased all of the material that had been shot. Rickleton appeared in person on social networks with a black eye, explaining that he had “fallen onto the knee of the officer who had detained him.”

The short-term detention of journalists covering the elections was condemned by Kazakhstani and international human rights advocates. Mihra Rittmann, senior Central Asia researcher for the international human rights organisation Human Rights Watch, declared on her Twitter account that the journalists had been detained short-term “in the exercise of their professional duties”, and all the other people “for attempting to exercise their right to peaceful protest.”

“The detention of journalists covering the elections is nothing more than direct interference in their work and their task of covering an event of deep public interest,” said Daisy Sindelar, Acting President of the media corporation Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. On 13 June, at a government briefing by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Deputy Interior Minister Marat Kozhayev apologised. He justified police action by saying journalists had not worn any clear external attributes to identify them as journalists.

8/ ACCUSATION OF LIBEL, INSULT, AND REPUTATIONAL DAMAGE

Accusations of libel, insult, and reputational damage are actively used against media workers throughout the entire period of the study. From 2017 through 2019, professional and citizen journalists experienced 154 instances of attacks/threats in this sub-category.

Even though most court trials end in acquittals, the indictment itself and the judicial inquiry are accompanied by significant moral and financial costs. If convicted, a journalist can be sent to prison for a term of up to three years.

Two court trials took place in 2019 in the course of which journalists were sentenced to deprivation/restriction of liberty after accusations of libel, insult, and reputational damage.

- On March 16, Yelena Kuznetsova, editor-in-chief of the Kvartal newspaper (city of Petropavlovsk, Northern Kazakhstan), was sentenced to one year of restriction of liberty. On June 18, the appellate court quashed the trial court’s verdict and fully exonerated the journalist.

- The conviction of Amangeldy Batyrbekov (Southern Kazakhstan) to two years and three months provoked an immense public outcry. Thanks to a public campaign, the guilty verdict was quashed in the appellate court, while the journalist, having by that time spent more than three months behind bars, was found not guilty.

9/ SHUTTING DOWN A MEDIA OUTLET / BLOCKING AN INTERNET SITE

Independent internet media outlets, social networks, and instant messenger services are a source of alternative information for Kazakhstanis. For this reason they are actively blocked by the authorities during mass demonstrations in the country.

- In 2017, two independent media outlets were forced to shut down – the internet media outlet Radiotochka(the shutdown was associated with the forced quitting of the profession by the head of the publication, B. Gabdullin) and the newspaper Sayasi Kalam: Tribuna (shut down by the owner in connection with the arrest of the editor-in-chief Zhanbolat Mamay).

- In May 2018, a court decision discontinued issuance of one of the most popular publications – the news-and-analysis internet resource Ratel.kz. Its operations were renewed in November 2019 by an appellate-level court decision.

- Kazakhstanis experienced a complete block of social networks and internet media outlets on Victory Day, May 9, 2019. From the early morning onwards, access to 13 internet media outlets was terminated, and after a short time YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, and Telegram turned out to be blocked. The only social network that remained unblocked was Twitter.

Kyrgyzstan

1/ KEY FINDINGS

101 instances of attacks/threats against professional and civilian media workers and the editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Kyrgyzstan were identified and analysed during the course of the study. The data for the study were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Kyrgyz, and English languages using the method of content analysis. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 4.

- The main type of attacks on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in Kyrgyzstan are attacks via judicial and/or economic means.

- The main methods of pressure on journalists are interrogations, wrongful charges of extremism and inciting different kinds of hate, a ban on leaving the country, and shutting down/blocking of media, while the source of the pressure is representatives of the authorities.

- 2017 became the year of the largest number of high-profile lawsuits for multiple millions in damages against media outlets and journalists in Kyrgyzstan.

- From 2017 through 2019, the number of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats increased five-fold.

- Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health recorded in relation to journalists and media workers are most often perpetrated in a period when they are carrying out their professional duties.

2/ THE MEDIA IN KYRGYZSTAN

According to the data of the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan, there are 2,048 media outlets registered in the country, including television, radio, online media, and print publications, coming out mainly in the Kyrgyz and Russian languages. Some media outlets, mainly in the south of the country, have an Uzbek-language version.

According to the assessments of local human rights groups and media research organisations, only about a third of the officially registered media outlets are actually operational. Most often this is associated with financial instability and the modest size of the advertising market.

The media sphere of Kyrgyzstan is represented primarily by independent media outlets, among which there is one public channel, four state-owned ones, and more than 20 private television and radio channels. The freest ones are the online media, of which there are more than 30 in the country. They present readers with various points of view. The concept of internet media does not exist in the legislation of Kyrgyzstan, on account of which online media can allow themselves to broadcast more objectively.

As of June 2019, the level of internet penetration in Kyrgyzstan is 40.1% according to Internet World Stats data. According to the Freedom of the Net 2019 report prepared by the Freedom House international human rights organisation, Kyrgyzstan has fallen several notches in the world internet freedom rating, which decline is associated with technological attacks on internet news publications in 2019. The authorities’ ongoing struggle against extremism leads to censorship of websites; there are articles in the Criminal Code of the KR that can be used for repressive purposes.

Kyrgyzstan took 83rd place in the Reporters Without Borders NGO’s World Press Freedom Index for 2019. The situation with freedom of the press in the country had improved in a year: in 2018 Kyrgyzstan had occupied the 98th row in the rating.

3/GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

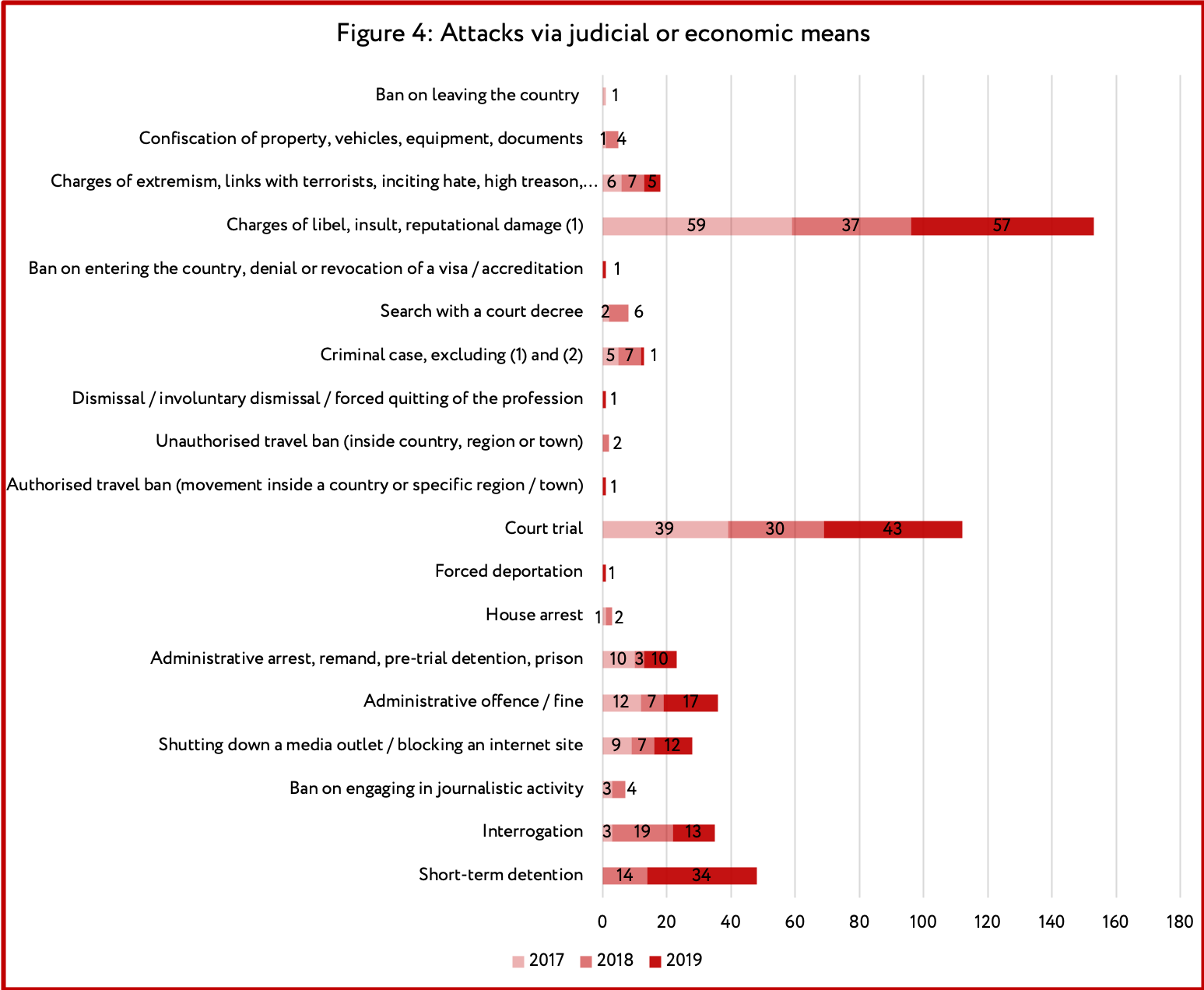

Figure 1 presents the overall number of attacks on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in Kyrgyzstan from January 2017 through December 2019.

Non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats increased by almost five times from 2017 through 2019. While only four had been recorded in 2017, by the end of 2019 there were 19. Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health increased from three in 2017 to seven in 2019. By contrast, the number of attacks via judicial and/or economic means fell slightly in comparison with 2017.

A number of attacks and threats, most often non-physical and/or cyber-, were not included in this monitoring. Constantly facing this type of attacks — trolling, cyber-harassment, and cyber-threats — journalists and bloggers do not always react to aggression and do not record the number of threats on the internet, preferring not to report about this to human rights groups.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, HEALTH, AND LIBERTY

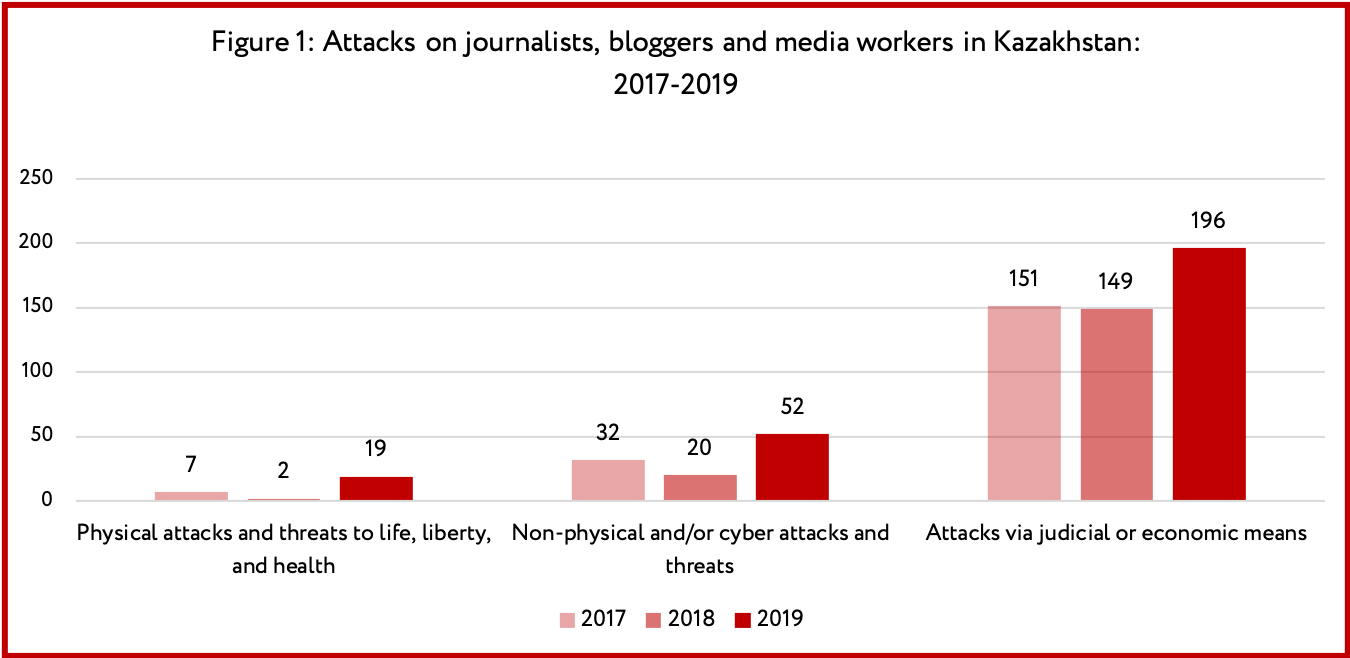

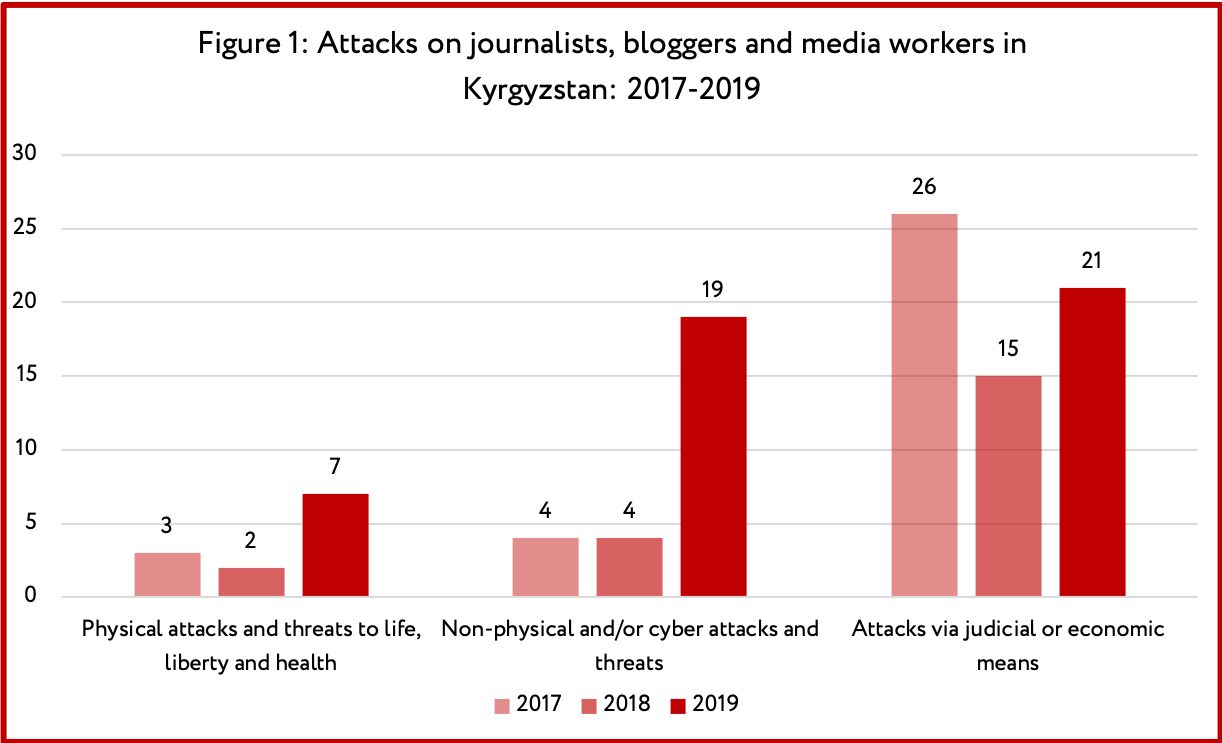

Figure 2 shows physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health. All of the physical attacks were non-fatal. The greatest number of attacks (7) was recorded in 2019. Nine out of the 12 non-fatal attacks over the period from 2017 through 2019 were perpetrated in relation to journalists when they were directly carrying out reporter work. This kind of attacks was recorded in relation to groups of journalists:

- In November 2018, a headline-making traffic incident took place involving Inga Sikorskaia, a journalist, media expert, and head of the School of Peacemaking and Media Technology. As a result of the automobile accident, which occurred on a Saturday night on an empty road, the taxi in which Sikorskaia was riding crashed into a car parked on the verge. The passenger suffered injuries and a concussion. The incident occurred 2 days after a night-time attack by unknown perpetrators on the School of Peacemaking and Media Technology office, where employees were holding open counselling sessions on freedom of expression.Since 2017, Sikorskaia has been subjected 19 times to meticulous screenings, body searches, and short-term detentions on the part of border guards when leaving and entering the country.

- In May 2019, the Radio Azattyk journalist Ydrys Isakov was beaten up whilst filming at the place where an underground casino is allegedly located in the city of Osh in southern Kyrgyzstan.

- In August 2019, whilst covering the storming of the home of former Kyrgyzstan president Almazbek Atambayev in the village of Koi-Tash 20 km south of Bishkek, two media workers were directly harmed by representatives of the authorities. Aida Dzhumasheva, a journalist for the 24.kg news agency, was wounded by a rubber bullet, while cameraman Zhoodar Buzumov was subjected to a physical attack.

- Assaults on investigative journalists from the Kloop.kg portal in November 2019 and on an Azattykcameraman in September of the same year took place prior to hacker attacks on the media outlets at which they work. According to media reports, Aibek Kulchumanov, a cameraman for the Radio Liberty Kyrgyz service, was conducting a video shoot in the city of Osh in southern Kyrgyzstan, near the house of a former deputy chairman of the Customs Service. At this moment, unknown people ran out from the territory of the house, twisted the journalist’s arms behind his back, and confiscated the remote control for a drone, a telephone, and video cameras.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

The most high-profile incidents in this category became the hacker attacks against a number of Kyrgyzstani online media outlets and websites in late December 2019. At that time, nine internet sites, ones like Factcheck.kg, Ecomonist.kg, Kloop.kg, Kaktus.media, Sokol.media, Vb.kg, Knews.kg, Today.kg, andPolitklinika.kg, were subjected to a massive DDoS attack.

The local media reported on this, while Radio Liberty’s Kyrgyzstan service Azattyk linked these attacks with the publication on the websites mentioned above of the results of a journalistic investigation that had been carried out in conjunction with Bellingcat. The investigation revealed the expensive purchases made by the spouse of former deputy chairman of the State Customs Service Raiymbek Matraimov and the discrepancy between the sums of the purchases and the government official’s official income statements.

Wiretapping and surveillance without a court decree were yet another kind of attacks identified in the monitoring period. A high-profile journalistic investigation conducted in 2019 by the Kyrgyz service of Radio Liberty, Azattyk, in conjunction with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and a team of journalists from Kloop.kg, was accompanied by threats and surveillance. This investigation was devoted to the shady schemes that had been used for years at Kyrgyzstan’s customs, allowing millions of dollars to be siphoned out of the country. Kloop.kg editor-in-chief Eldiyar Arykbayev confirmed to the kaktus.media publication that his colleagues had received threats on the part of unknown persons during the investigation: “They were approaching our employees and telling us not to engage in this investigation. In Osh we were under surveillance. It lasted several days.”

6/ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL OR ECONOMIC MEANS

Attacks via judicial and/or economic means were the most common method of pressure on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in Kyrgyzstan in the years from 2017 through 2019, despite a slight decline in their numbers in 2019. 2017 became a year of high-profile lawsuits for multiple millions in damages against media outlets and journalists in Kyrgyzstan. In 2017, the authorities declared open season on bloggers who criticised the president on the social networks. The State Committee for National Security (GKNB) reported that it was “implementing measures to identify 35 users in response to the dissemination and posting of negative publications addressed to the head of state”.

Widely used methods of pressure are interrogations, court trials, wrongful charges of extremism and inciting different kinds of hate, bans on leaving the country, and shutting down a media outlet/blocking an internet site. Media workers have their freedom of movement restricted, either by court decree after the initiation of cases against them, or by way of placing the journalists and media workers on blacklists for the conducting of personal security screenings/searches when they are entering or leaving the country.

- In January 2018, a court demanded that the flat of Naryn Aiyp, a political observer and co-founder of the Zanoza.kg web portal, be put up for public bidding. Earlier, former president Almazbek Atambayev had reckoned that the publication had insulted his honour and dignity and had been disseminating false information.

- On August 9, 2019, armed special forces fighters broke into the office of the Aprel television channel in Bishkek, kicked out all the employees, and sealed off the building. Earlier, the authorities had turned off the channel’s satellite signal whilst it was providing live coverage of a special operation to detain former president of Kyrgyzstan Almazbek Atambayev short-term at his residence. The authorities declared that the closure and blocking of the television channel are associated with the freezing of the assets of the former president, who owns the Aprel television channel.

- In November 2019, Aftandil Zhorobekov, the administrator of the BespredelKG Facebook page, was arrested for “inciting inter-regional hate”. He was held in custody until the trial on December 5, after which it was decided to place Zhorobekov under house arrest. A few days later, the State Committee for National Security (GKNB) re-classified his charge to “disseminating knowingly false and inflammatory information about how the current head of state is allegedly an accomplice in a corruption offence”. The blogger had posted a post and photographs on the internet page criticising the targets of a journalistic investigation into corruption at Kyrgyzstani customs.

The peak in lawsuits came in 2017-2018.

- In June 2017, a court decreed that nine million Kyrgyz soms ($129,000) be recovered from Naryn Aiyp, a political observer and co-founder of the Zanoza.kg web portal, for “disseminating information discrediting the honour and dignity of the president” in a critical article.

- In June 2017, a court found the Zanoza.kg portal and its co-founders Dina Maslova and Naryn Aiyp guilty for articles critical of president Atambayev, and decreed the payment of multiple millions in fines.

- In June 2017, a criminal case was started up in relation to Ulugbek Babakulov, a journalist with the Ferghana Information Agency, under the criminal code article “inciting inter-ethnic hate. He was accused of publishing a series of articles “of an incendiary nature, aimed at inciting inter-ethnic enmity and hate, creating the prerequisites for the exacerbation of inter-nationality relations”.

- In August 2017, the Sentyabr television channel was shut down by a court decree with the wording “in connection with the dissemination of extremist materials”.

- On September 21, 2017, a lawsuit was filed against 24.kg agency journalist Kabai Karabekov for five million Kyrgyz soms (around $72,000) in defence of the honour and dignity of presidential candidate Sooronbai Zheyenbekov. The journalist had written about the candidate’s and his brothers’ ties with certain Arab organisations.

- On December 9, 2017, the authorities deported Chris Rickleton, a journalist with Agence France-Presse, from the country. According to the official story it was “for violation of visa requirements”, even though he had been denied accreditation without an explanation of the reasons since 2016.

- On December 19, 2017, an arrest was imposed on the property and radio frequencies of the NTS television channel.

- On February 14, 2018, the financial police brought charges against Elnura Alkanova, a journalist at the Ferghana Information Agency, for “illegally obtaining and disseminating documents containing a commercial secret”. Earlier, the State Service for Combating Economic Crimes had opened a criminal case in relation to Alkanova in connection with disclosing a banking secret. The journalist had been investigating a purchase of single-family luxury homes in which high-ranking government officials were involved.

Tajikistan

1/ KEY FINDINGS

81 instances of attacks/threats against professional and civilian media workers and the editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Tajikistan were identified and analysed during the course of the study. The data for the study were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Tajik, and English languages using the method of content analysis. Material that has previously not been made public and was obtained using the expert interview method was likewise used in the report. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 5.

Considering the specific features of Tajikistan and the heightened risks for journalists, not all media workers are prepared to share information about how they had been subjected to threats and attacks. At best, they might recount this in a personal conversation with colleagues; at worst, they will try to conceal it from everybody in order to not subject themselves to new persecution. Incidents of persecution of Tajik journalists who have fled Tajikistan and received asylum in European countries are not greatly publicised as a rule.

- The main type of attacks on media workers in Tajikistan are attacks via judicial and/or economic means, above all charges of extremism or of links with terrorists, the initiation of criminal cases, and deprivation of liberty of media workers.

- The main source of such a kind of attacks are representatives of the authorities.

- From 2017 to 2019, the number of identified attacks on the part of representatives of the authorities, as well as of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats, increased three-fold on average. This rise is associated with the approach of two important political events in Tajikistan – the general and presidential elections, which are going to be held in March and November of 2020.

- The targets of the attacks are most often not the journalists themselves, but their relatives, who are subjected to various kinds of persecution, including interrogations and searches.

- The coverage of any topics associated with the Islamic Renaissance Party, which is banned in Tajikistan, is likewise prohibited, while journalists who bring up this topic are subjected to pressure, in the form of charges of links with terrorists and criminal prosecutions.

2/ THE MEDIA IN TAJIKISTAN

376 newspaper titles are officially registered with the Ministry of Culture of Tajikistan (112 state-owned and 264 non-state-owned), along with 245 magazines (114 state-owned and 131 not), 71 publishing houses (10 state-owned and 61 not) and 11 news agencies (one state-owned and 10 not).

There are likewise 34 officially registered television channels (8 state-owned and 26 non-state-owned) and 30 radio stations (6 state-owned and 24 not).

The work of the media is severely restricted by the Tajik authorities. Article 137 of the Criminal Code of Tajikistan prohibits “slandering” the president, while Article 330 prohibits journalists from insulting other government officials. Journalists who write critical articles are subjected to threats and persecution, and may be charged with various crimes. For this reason, most Tajik journalists practice self-censorship.

The government controls most of the country’s printing houses, newsprint suppliers, and broadcast media. Since February 2017, printers and print media have only been able to register with the Ministry of Culture after obtaining written permission from the State Committee for National Security of Tajikistan.

The Media Licensing Commission of Tajikistan regularly denies licenses to independent media or impedes the license extension process. At the present time, the Licensing Commission, which was established under the State Committee for Television and Radio Broadcasting, does not include a single representative of independent media or civil society.

Since the launch of the Unified Switching Centre (USC), through which all internet traffic passes and is controlled, blocking of websites and social networks has become a regular practice. The USC likewise allows for tracking private individuals’ traffic and prosecuting them for visiting “undesirable” websites or making “inappropriate comments” on the internet.

In July 2018, Tajikistan’s parliament adopted a new law on domestic intelligence activity that allows law enforcement agencies to legally obtain data on the online activity and text messages of the country’s citizens. In August 2018, Tajikistan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs created a new agency to combat extremism on the internet, emphasising this as a government priority.

Tajikistan took 161st place of 180 in the Reporters Without Borders NGO’s 2019 World Press Freedom Index, dropping 12 places compared with 2018.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

Figure 1 represents a quantitative analysis of the three main types of attacks against journalists on the territory of Tajikistan and on Tajik journalists who have fled Tajikistan but continue to conduct professional activities abroad in the period from 2017 through 2019 inclusive.

The number of attacks on journalists via judicial and/or economic means and non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats more than tripled from 2017 through 2019. The number of physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health remained virtually unchanged.

It should be noted that cyber-attacks and threats are not recorded as a rule, inasmuch as media workers attach little importance to them, with the exception of cases where news portals are subjected to illegal blocking. But in none of the cases studied did the authorities officially confirm their involvement in the blocking, citing technical problems instead.

Cyber attacks and non-physical threats on the internet have become commonplace for Tajik journalists. As journalists have been able to establish, the security services in Tajikistan have set up a “troll farm” that numbers more than 400 employees, each of whom has 10 fake accounts. Employees of agencies subordinate to the Ministry of Education and Science –instructors at higher education establishments and general-education school teachers – are recruited for its activities. The “trolls” receive assignments from the Ministry of Education, which in its turn receives the appropriate command from the Ministry of Internal Affairs or the State Committee for National Security. The trolls are ordered to begin a campaign on the social networks to defame civic activists or opposition supporters immediately or on a specific day. Media employees have become so accustomed to this that they no longer view it as a threat.

Relatives of at least six journalists who fled Tajikistan have been subjected to fierce pressure during the reporting period. Another four journalists who have been granted asylum in European countries have been added to the list of persons who have links with terrorists.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

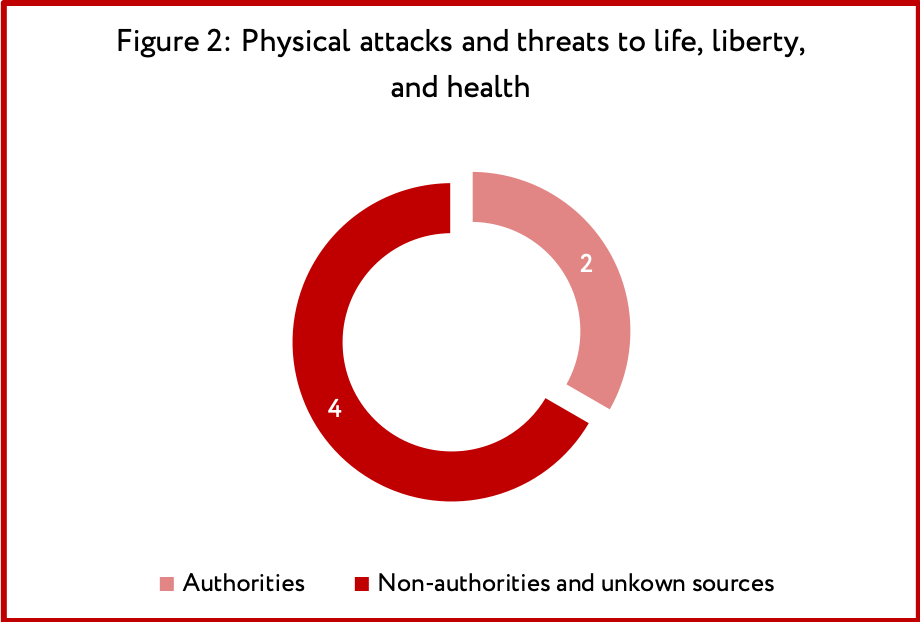

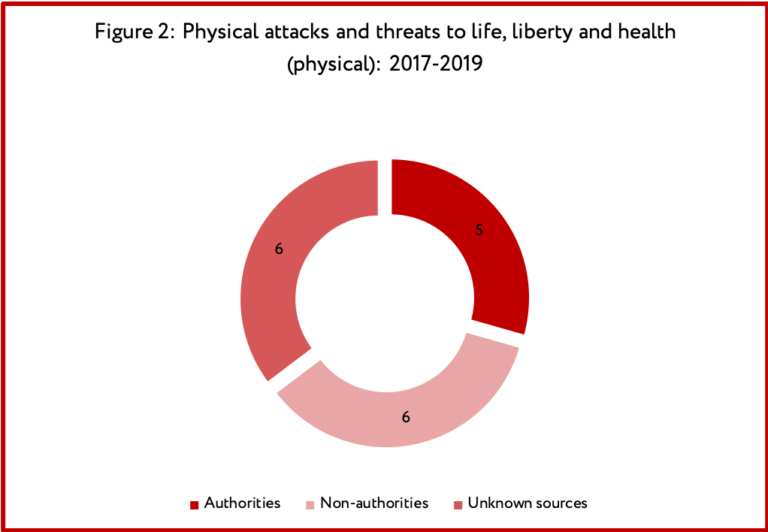

Figure 2 depicts physical attacks on journalists in Tajikistan. 6 incidents were registered during the indicated period, one of which was fatal.

- Sputnik journalist Galim Faskhutdinov was hit by a car as he was crossing the road at a pedestrian crossing at a green light. The automobile was moving at a high speed. The driver responsible for this incident was sentenced to the minimum term of 3 years and 3 months of deprivation of liberty. The family of the deceased journalist never did receive the monetary recovery set by the court.

- Two instances of non-fatal physical attacks were recorded whilst the journalists Nisso Rasulova and Mahasti Dustmurod were carrying out their professional activities at an illegal market for mobile phones.

- Opposition journalist Abdukakhkhor Davlat, serving a lengthy sentence on charges of extremism and terrorism, was injured during a riot at a penal colony in Vakhdat on May 19, 2019. According to the official story, the riot was caused by members of the banned Islamic State organisation who were serving sentences at the institution.

In the three years, two instances were published of physical attacks by representatives of the authorities; moreover, in the first case, it was not the journalist himself who was the victim, but his father:

- In September 2017, the father of journalist Muhammadzhon Kabirov was detained for two days because of the son’s participation in an OSCE conference in Warsaw.

- In October 2019, Asia-Plus journalist Abdullo Gurbati was forced into an automobile by people in police uniforms and taken to a military induction centre to undergo military service. He was later released after urgent phone calls to the leadership of the city department of internal affairs.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

Incidents falling within the category of non-physical attacks — harassment/intimidation/pressure/threats of violence and death, including cyber- — rarely find reflection in the media. This occurs because the victims themselves fear further repressions against themselves and their loved ones.

A typical feature of attacks on Tajik media workers is that threats and attacks on their closest relatives are used in order to pressure them. The authors of this report know of at least one case where a journalist received personal threats of violence and physical reprisals against himself and his children. This incident was not reflected in the media.

In the published incidents, attacks on relatives of opposition journalists and journalists living abroad were being perpetrated by representatives of the authorities via judicial means (see section 7 — CRACKDOWN ON JOURNALISTS BEYOND THE CONFINES OF THE COUNTRY).

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL OR ECONOMIC MEANS

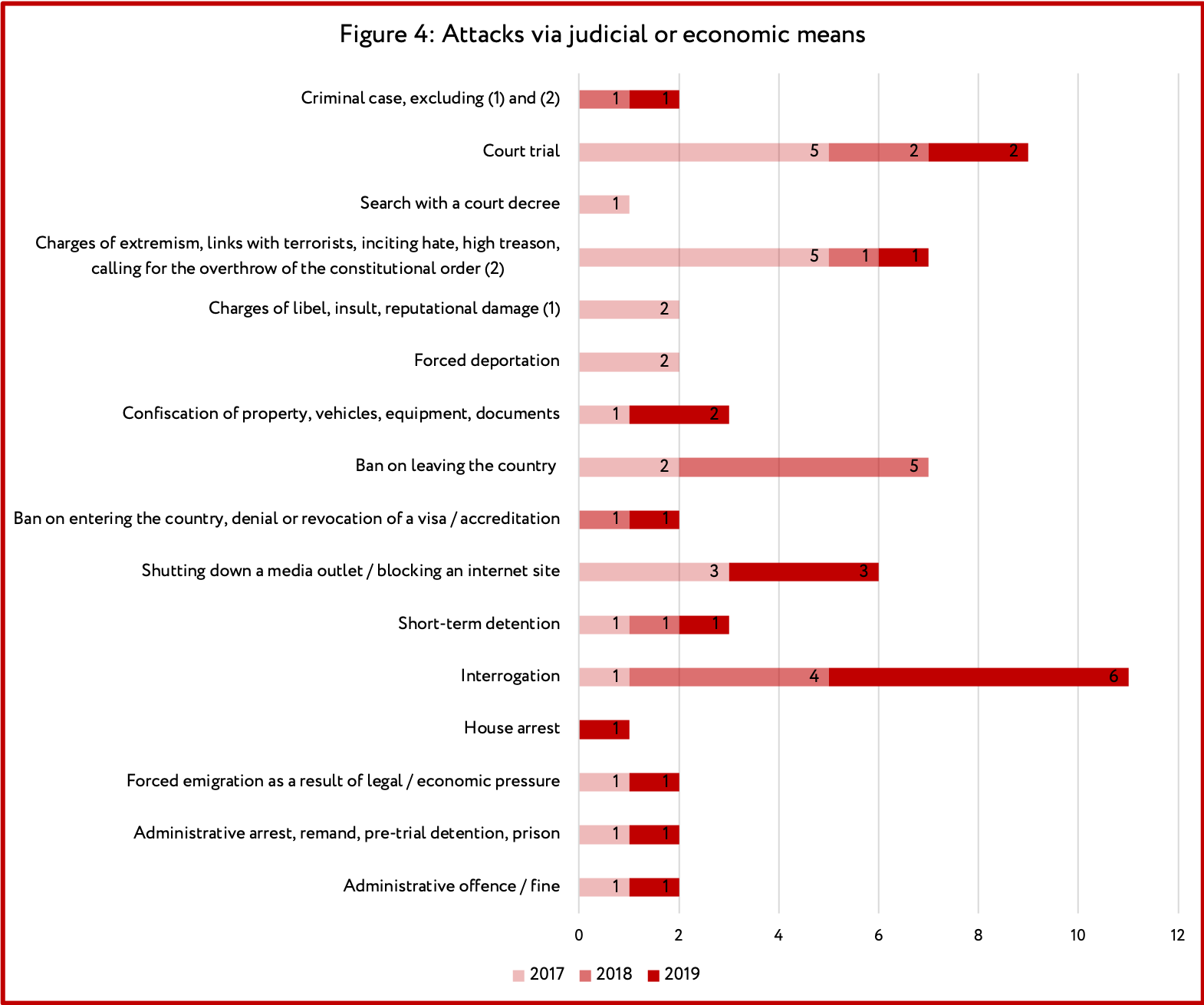

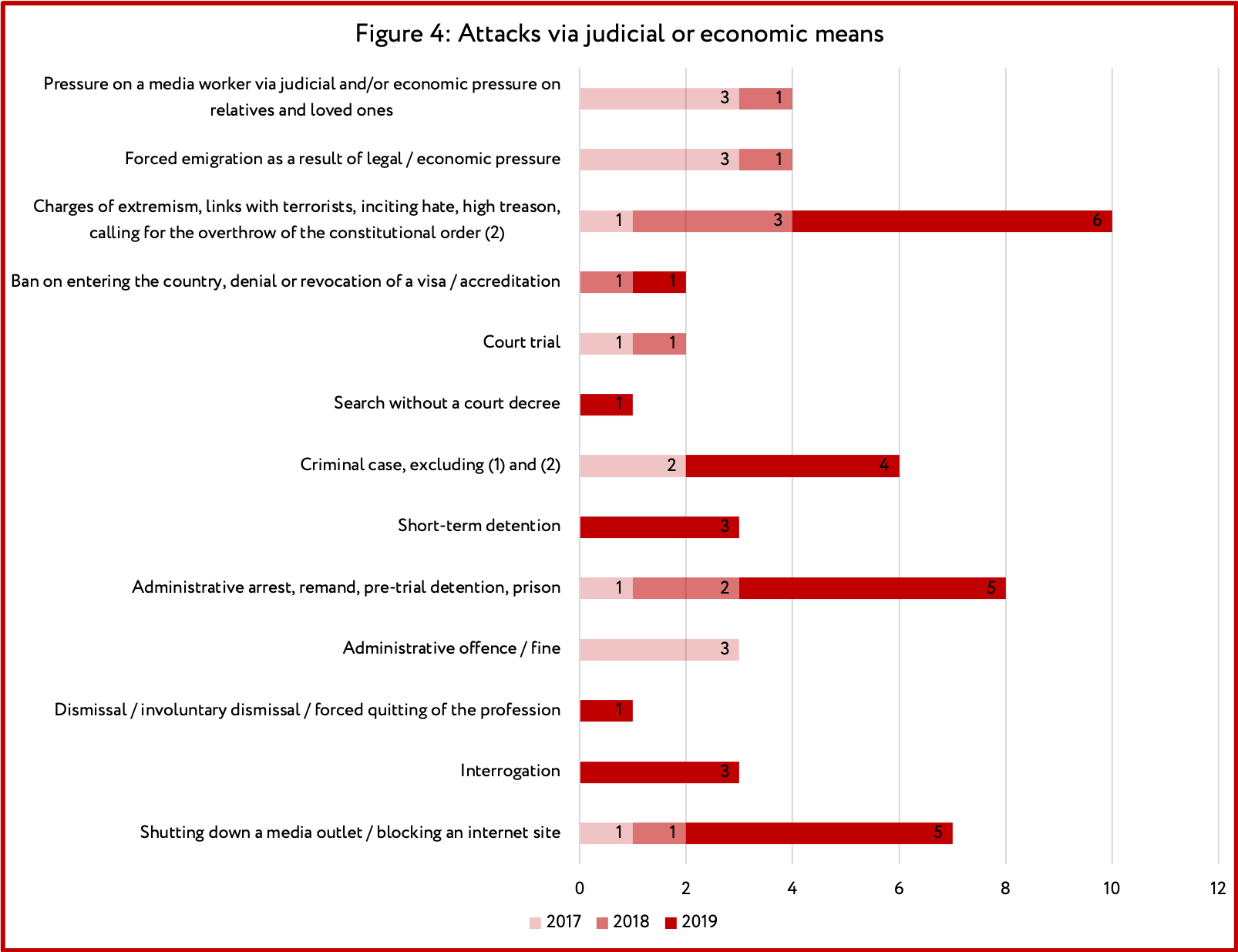

Figure 4 presents the various sub-categories of attacks via legal and/or economic means. The most widespread method of pressure on journalists and media workers in Tajikistan are criminal cases on charges of extremism, links with terrorists, and libel, and under other articles of the criminal code. As a rule, trials of media workers end in convictions. Yet another method of pressure is shutting down a media outlet and blocking an internet site.

- In May 2017, Midzhgona Khalimova was put on trial; the authorities charged her with not reporting a crime and sentenced her to paying a fine of 2,800 US dollars, which is a large sum for Tajikistan. The young journalist’s problems began after she began asking government officials tough questions at press conferences. Khalimova also refused to take off the hijab — a Muslim headscarf. National Committee for State Security employees gave the journalist’s employers a choice: either they dismiss her or the media outlet will be shut down. At the present time, Khalimova is unable to find a full-time job: potential employers reject her in advance in order to avoid problems with the authorities.

- On July 11, 2018, a court sentenced Khairullo Mirsaidov to 12 years’ deprivation of liberty. The independent journalist’s crime was to have spoken out about corruption in the Sughd Oblast [Viloyat] administration through the media. His family paid around 13 thousand dollars to the state budget as recovery for the damages that Mirsaidov had caused to the state as determined by the investigative agencies. After lodging a cassation appeal, Mirsaidov was released in the courtroom. On January 11, 2019, the Khujand City Court, relying on a court marshal’s statement that the journalist had fled the country without the authorities’ knowledge, sentenced Mirsaidov in absentia to eight months’ deprivation of liberty.

Other blatant examples of the authorities interfering with the work of the media include taking away their domain names or revoking their accreditation.

- The Asia-Plus news agency had two domain names taken away – news.tj and asiaplus.tj.

- On November 1, 2019, 11 employees of Radio Ozodi, the Tajik service of Radio Liberty, had their accreditation taken away.

7/ CRACKDOWN ON JOURNALISTS WORKING BEYOND THE CONFINES OF THE COUNTRY

On the eve of the general and presidential elections that will take place in Tajikistan in March and November 2020, the attitude of the authorities towards journalists who have been forced to leave the country is changing. As the elections approach, the pressure on journalists who had been forced to flee the country is increasing: the number of attacks has risen in comparison with 2017.

- In October 2019, four journalists were added to the list of persons involved in terrorism. Their relatives in Tajikistan are being subjected to persecution – not only searches and fines, but also intimidation on the part of representatives of the law enforcement agencies.

- In October 2019, the sister of journalist Shukhrat Rakhmatullo was detained short-term for wearing a Muslim headscarf. Shukhrat himself is on the list of persons involved in terrorism, and had earlier been forced to flee Tajikistan. His sister was subjected to threats of physical reprisals and humiliating treatment in the course of the short-term detention.

- In November 2019, an investigative check was begun in relation to the Akhbor news portal, which had been created by a Tajik journalist beyond the confines of the country.

Turkmenistan

1/ KEY FINDINGS

During the course of the investigation, 33 cases of assault and intimidation against professional media workers, citizen journalists, civil activists and editorials of traditional and online media in Turkmenistan were uncovered. The data for this investigation was gathered through the content analysis of open sources in Turkmen, Russian and English languages. Information not formerly made public but obtained through expert interviews has also been incorporated in the report. For a list of the main sources, see Appendix Six.

The heightened risks faced by dissidents in Turkmenistan and the country’s highly restrictive media environment mean that we remain unaware, necessarily, of many attacks on freedom of speech.

- The main form of intimidation deployed against media workers in Turkmenistan is the application of legal and economic pressure. Such intimidation is often accompanied by physical assaults and threats to the life, liberty and health of those workers.

- The authorities in Turkmenistan are the principal source of threats and pressure against media workers and journalists. They use arrests and custody accompanied by interrogation and torture to bring media workers into line, or hand out dismissals and bans on working further in the media.

- Citizens suspected of working for foreign media by the authorities and the secret services are added to a list of “untrustworthy citizens”. Together with family and close friends, they become subject to constant pressure and harassment.

- State-owned telecommunication provider Turkmentelekom is the only communications operator in the country. This enables the authorities to intercept any information that correspondents attempt to transmit to foreign media outlets.

- Turkmenistan is one of the few Soviet successor states where punitive psychiatry continues to be used against “untrustworthy” citizens, including those working for the media or providing media workers with information.

2/ MASS MEDIA IN TURKMENISTAN

Since 2015, Turkmenistan constantly ranked one of the last places (177-178) in the World Press Freedom Index 2019 issued each year by Reporters without Borders. In 2019, it dropped to the very last place (180) on the list, being overtaken by Eritrea and North Korea.

Prior to 1997, more than thirty national newspapers, five regional branches of Gosteleradio (the State Radio and Television Committee), and six regional newspapers – five published in Russian, one in the Uzbek language – were all closed down.

At present, 24 newspapers and 20 magazines, almost all in the Turkmen language, are being published in Turkmenistan. Three newspapers (Turkmenistan, Neutral Turkmenistan and the Published Herald of the President of Turkmenistan) and one magazine (Diyar) are officially published by the Turkmenistan Cabinet of Ministers. The remaining media outlets are published by ministries and government departments: they are considered State-owned and are funded from the State budget.

Seven TV channels and four radio stations operate within the country. They broadcast only in Turkmen and, like print media, are State financed. By law the media are independent in Turkmenistan; in practice, newspaper and magazine editors, and their deputies, are all appointed and dismissed by the president.

Those who have studied journalism in other countries are not allowed to work for Turkmenistan’s State-run media. Every media student must obtain his or her diploma in accordance with the relevant laws and requirements, and demonstrate loyalty to the regime and its policies. It is forbidden to criticise the authorities. As a consequence, many young journalists either leave the country or do not follow their chosen profession.

Foreign journalists cannot receive accreditation to work in Turkmenistan. Those permitted to practice journalism within the country can only do so if they adopt a positive attitude to the authorities. All foreign internet resources and media outlets offering objective information about the situation in Turkmenistan are blocked, as are the websites of many social networks and services for the exchange of files and messages. The regime has purchased specialised equipment from leading Western producers to keep anyone who reveals information about the situation in the country under surveillance.

3/ ATTACKS THAT ENDANGER LIFE, HEALTH AND LIBERTY (PHYSICAL)

Since 2006, the following cases are known from open sources and specialist information.

- There have been sixteen assaults on journalists and Turkmen citizens working for foreign media, inflicting various levels of physical injury.

- Three individuals who criticized the existing regime in foreign media have been forcibly confined to psychiatric clinics (or alcohol and drug treatment centres):

- Gurbandurdy Durdykuliyev was held in a psychiatric treatment centre in the Lebap Province from 13 February 2004 to April 2006.

- A freelance employee of Radio Azatlyk, the Turkmen-language branch of Radio Liberty, Sazak Durdymuradov was arrested, tortured and told he must stop working for foreign media. On 18 June 2008 he was forcibly confined to a psychiatric clinic.

- On October 4, 2012 Geldymurad Nurmukhamedov, a former Communist Party official and Turkmenistan Minister of Culture was forcibly confined to the Tejen drug treatment centre for nine months after an interview on Radio Azatlyk in which he talked about violations of human rights and the lack of democracy in Turkmenistan.

- The deaths of two journalists in obscure or mysterious circumstances.

- In September 2006 Ogulsapar Muradova, a correspondent of Radio Azatlyk, died in prison in unclear circumstances. Relatives found marks on her body, indicating that she had been killed. There was a cut on her forehead, signs of choking around her neck, open wounds on one hand, bruising on a knee, and a large bruise on her thigh. At first the Turkmenistan authorities announced that Muradova’s death was the result of “natural causes”. Later they claimed that she had committed suicide. The UN Committee for Human Rights declared in 2018 that Turkmenistan was responsible for torturing and killing Ogulsapar Muradova.

- The 68-year-old writer and playwright Amanmurad Bugayev died in a car accident on 3 April 2019 during a tour of the Balkan Province. Bugayev, an occasional Radio Azatlyk correspondent and renowned author, died in an accident, observers believe, that was organised by Turkmenistan’s Ministry for National Security to eliminate a troublesome journalist.

4/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL OR ECONOMIC MEANS

Journalists, bloggers and other media workers whom the authorities suspect of collaborating with foreign media organisations are frequently subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention and the use of direct threats of physical violence by representatives of the authorities. Media workers are often called for questioning to local police and security service departments; their mobile phones are confiscated and checked; unauthorised searches of their homes are conducted; and all their correspondence is read or listened to. In addition, they are kept under constant surveillance.

In 2017-2019, there were at least five such cases when evidence against those who provided information to the foreign media from inside Turkmenistan, was gathered by studying CCTV cameras’ footage and comparing it with the video images or stills published by independent Turkmen media. Journalists are also tracked by their internet traffic, when sending large files (as mentioned earlier, there is only one State-controlled telecommunications firm in the country, Turkmentelekom.) In all of the five cases, media workers were called to a police station on some other pretext, after which they were interviewed by staff from the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Journalists were shown evidence of their links to various publications (screenshots, CCTV footage, transcripts of conversations or internet traffic) and were threatened with the consequences of pursuing such “anti-State” activities.