Authors of the report

Non-profit journalistic non-governmental organisation. It was officially registered on 16 January 2003. Throughout its existence the organisation implemented more than 40 projects. The Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression is a member of the Armenian National Platform of the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum and has actively taken part in the activities of the Forum.

The main direction of the CPFE activity is the monitoring of the free speech situation in Armenia, detection of and responding to the violations of the rights of journalists and the media, as well as drafting and publication of periodic reports on the basis of the above data. The CPFE also takes practical steps to protect the rights of the media and their representatives, including before courts. An important area of the Commitee’s activities is the improvement of the media-related legislation. With a view to this, the CPFE drafts new legislation and amendment packages and submits them to the parliament.

- Georgia: Oleg Panfilov

Georgian journalist, commentator and writer. Author of 52 books and of more than one hundred TV programmes about Georgia. He has won various international prizes and is a Cavalier of Georgia’s Order of Honour. In the 1990s, he headed the Moscow bureau of the Committee to Protect Journalists (1992-1993), and was in charge, from 1994 to 1999, of the monitoring service of the Glasnost Defence Foundation in Moscow, before setting up the Centre for Journalism in Extreme Situations (Moscow) of which he was director from 2000 to 2010.

One of the most important Moldovan non-governmental organizations providing assistance to independent media. API was founded in 1997 by the representatives of the first local independent newspapers.

API promotes press freedom and highly appreciated for its media campaigns in various public interest sectors, advocacy activities for mass-media development, defense of the freedom of expression, access to information, promotion of journalistic self-regulation, etc. API’s slogan is: “For a professional, objective and strong press”.

Since 2015, API and three other media NGOs organize yearly Mass-media Forum in Republic of Moldova, for discussion the problems and challenges faced by the journalistic community and draft a Roadmap for media development in Moldova.

- Photographers

“Photolure” News Agency (Armenia), Oleg Panfilov (Georgia) , Andrei Mardar (Moldova).

Introduction

The present research is part of an extensive study on attacks perpetrated against journalists, bloggers and media workers that covers 12 post-Soviet countries. This part of the study is devoted to Armenia, Georgia and Moldova.

The research has been jointly carried out by the Justice for Journalists Foundation and partners from those countries.

METHODOLOGY

The study is based on data collected by content analysis of open sources in Russian, English and the relevant state language. Lists of the main sources are given in Annexes 2-4. Expert interviews with journalists were also used in compiling the report.

Based on further analysis of 692 attacks perpetrated against professional and citizen journalists, bloggers and other media workers, three main types of attack were identified:

- Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health

- Non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats.

- Attacks via judicial or economic means.

Each of the categories of attack shown can be further divided into subcategories, a complete list of which is given in Annex One.

PRINCIPAL TRENDS

The total combined population of the three countries covered in this study comprises slightly more than 10 million persons. According to the Reporters Without Borders NGO’s World Press Freedom Index rating, these countries rank in the top 100 of the 180 states analysed in terms of freedom of speech: Moldova ranked 91st, Armenia 61st, and Georgia 60th. It is important to note that no media workers lost their lives in these countries in the three years covered in this study.

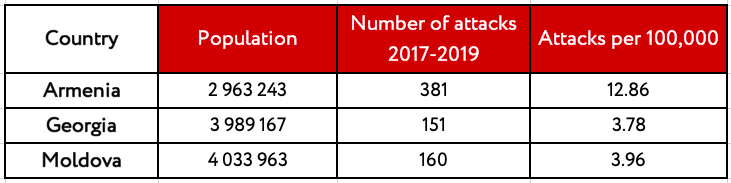

For a proper comparison of the numbers of incidents in these countries, it is advisable to give not the absolute numbers of attacks, but the relative figures – per 100 thousand people.

The relatively high indicator of the number of attacks in Armenia is explained above all by the well-functioning system of monitoring violations of journalists’ rights in the country. Although the number of recorded attacks per 100 thousand people in Georgia and Moldova is not that large, they are of a more aggressive and extralegal nature. While in Armenia the main method of resolving a conflict with a journalist is legal action, in Georgia physical assaults predominate, and in Moldova non-physical and/or cyber-assaults. The number of instances of legal action against media workers in these two countries is relatively low.

In Armenia, the number and the nature of attacks against media workers has correlated with political crises: the National Assembly elections in 2017 and the Velvet Revolution in 2018. The number of incidents of physical violence in relation to journalists fell sharply in the post-revolutionary period — the attacks moved from the streets to the courts. Thus, in 2019 there were only 6 physical assaults on media workers committed compared to 57 over the previous two years, but the number of legal cases against journalists and media outlets increased fourfold. Nearly all of the court cases concerned insults and libel in media publications; moreover, in 70% of incidents they were coming not from representatives of the authorities but from ordinary citizens representing various strata of society.

Over the last 11 years, there have been no recorded incidents of murder or attempted murder of journalists in Georgia. That said, the number of physical assaults on media workers in 2019 increased 13-fold compared to 2017. In 51 of the 64 cases, journalists suffered from the actions of the police or Interior Ministry special forces, as a rule in the course of their dispersion of protest actions. The number of attacks in the other categories likewise increased. Notably, all 48 instances of attacks via judicial and/or economic means recorded in the country over the three years came from representatives of the authorities. Analysts link the nearly fivefold increase in attacks against media workers with the rise in political activism in society in the run-up to the October 2020 general elections and the aspiration of Georgia’s authorities to quash opposition sentiments.

In Moldova, the overwhelming majority of attacks against media workers take place outside a legal framework. That said, they most commonly take the form of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats, above all illegal impediments to journalistic activity, wiretapping, surveillance without a court decree, harassment, intimidation, pressure, and threats of violence and death, including cyber-. However, the situation with physical assaults is also getting worse: in June 2019, during a political standoff in the country, 16 media workers suffered whilst covering political events and protest actions in the capital. In 60% of the cases, the source of all types of attacks/threats against media workers were representatives of the central and local/regional bodies of power, government officials, policemen, and representatives of the state security services.

THE RELEVANCE OF THIS STUDY

For a more thorough understanding of the processes that the post-Soviet states are going through, it is crucially important to keep a close watch on the dynamics of the situation with freedom of the media in countries whose populations have chosen a democratic path of development. Analysis of the attacks on media workers in Armenia, Georgia and Moldova shows a direct dependence between the level of development of civic institutions and the safety of the work of journalists.

In a situation of active political confrontation, conflicts between different social forces are as a rule resolved on the streets. For the journalists covering the protest actions, this is fraught with the risk of physical violence on the part of the police and representatives of government power structures.

In a more stable environment, other methods of pressure come to the fore, ones such as harassment, surveillance, and illegal impediments to the work of journalists, including via economic or judicial means. In conditions of poorly functioning legislative mechanisms and lack of confidence in the courts, violence and aggression against media workers become the main method for resolving conflict situations used by both representatives of the authorities and ordinary citizens.

The Justice for Journalists Foundation, together with its partners and experts, carries out weekly monitoring of attacks against media workers in all post-Soviet countries excluding the Baltic states, the results of which are published on the Media Risk Map in both Russian and English. The available data covers the period from 2017 onwards.

On March, 25 Index on Censorship and Justice for Journalists Foundation announced a joint global initiative to monitor attacks and violations against the media, specific to the current coronavirus-related crisis. Media freedom violations will be catalogued with a map hosted on Index’s current website.

Armenia

1/ KEY FINDINGS

381 instances of attacks/threats against professional and citizen media workers and the editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Armenia were identified during the course of the study. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Armenian, and English languages using the method of content analysis. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 2.

- In 2017-2019, the increase in the number of violations of the rights of journalists and media outlets in Armenia correlated with deterioration of the socio-political situation, above all with the Velvet Revolution in 2018.

- Physical attacks on journalists were intense in 2017, especially in the period of the elections to the National Assembly of the RA and to the Council of Elders of Yerevan, as well as in 2018 during the coverage of the Velvet Revolution. The number of instances of violence in relation to journalists declined sharply in the post-revolution period.

- In 2019, the most prevalent type of pressure on journalists and the media became attacks via judicial means: the number of court cases against journalists and media outlets increased four-fold. Almost all of the lawsuits concerned insults and libel in media publications.

- Members of the public appear as plaintiffs in such cases two and a half times more than representatives of the authorities.

- In 2019, the number of attacks of a non-physical nature against Armenian media workers fell by a third in comparison with 2017.

We do not make any claim that the statistical data cited by us here and below are absolutely precise. It is known that representatives of the media who have encountered attempts to hinder and obstruct their professional activity often decide not to make these facts public, ignore the threats, or prefer to resolve the problems that arise and overcome any illegal restrictions by themselves. For this reason, the real number of attacks on journalists and media outlets is much higher than what has been recorded. Nonetheless, the data gathered do enable us to form an impression.

2/ THE MEDIA IN ARMENIA

Official data on the number of media outlets in Armenia do not exist, since registration of media outlets is not required by the law “On the Mass Media”.

Based on broadcasting license data, there are two Public Television channels operating in Armenia. Besides them, 18 private television companies — both nationwide ones and those limiting their broadcasting to the capital — are based Yerevan. Among them there are also companies that rebroadcast the programmes of foreign television channels: the Russian RTR-Planeta, Kultura, and Pervyi kanal [First Channel] and the inter-state Mir, as well as the American CNN. Of the 5 private Armenian nationwide channels broadcasting to the entire country, the ones with the highest ratings are Armenia and Shant. Oblast-level television companies operate in nine of the country’s 10 regions. Besides them, about 10 local television companies exist in various Oblasts [Marzer], but because of the short-sighted policy of the authorities, they have ended up being left out of the transition process to digital broadcasting and continue to operate in analogue mode.

There are 23 radio companies operating in Armenia, of which 3 broadcast on channels run by the Public Radio Service, 18 are private, and two broadcast on the basis of inter-state agreements. Of the 18 private radio companies, three are nationwide, 13 are limited to the capital, and two are Oblast-level.

According to data obtained from several press distribution agencies, about 20 newspapers with a print run of up to 5,000 copies are regularly published with a frequency from 1 to 5 times a week. Likewise being published are no more than ten magazines, which exist on account of sponsor support.

At the same time, the online media market is developing by leaps and bounds. Hundreds of news portals and internet publications exist in the country but, according to the ALEXA international rating system, only 45-50 of them play a noticeable role in the information landscape. The rest of the websites hardly produce any original content, and only reprint publications from better-known multimedia platforms, at times in violation of copyrights.

According to the data of a poll conducted by the Region Research Centre, 66% of the country’s population considers social networks to be its main source of news, 54% television, 51% online media, 5% radio, and 1% newspapers.

Armenia occupies 61st place out of 180 of the world’s countries in terms of the level of freedom of speech according to the data of the Reporters Without Borders NGO’s annual World Press Freedom Index for 2020.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

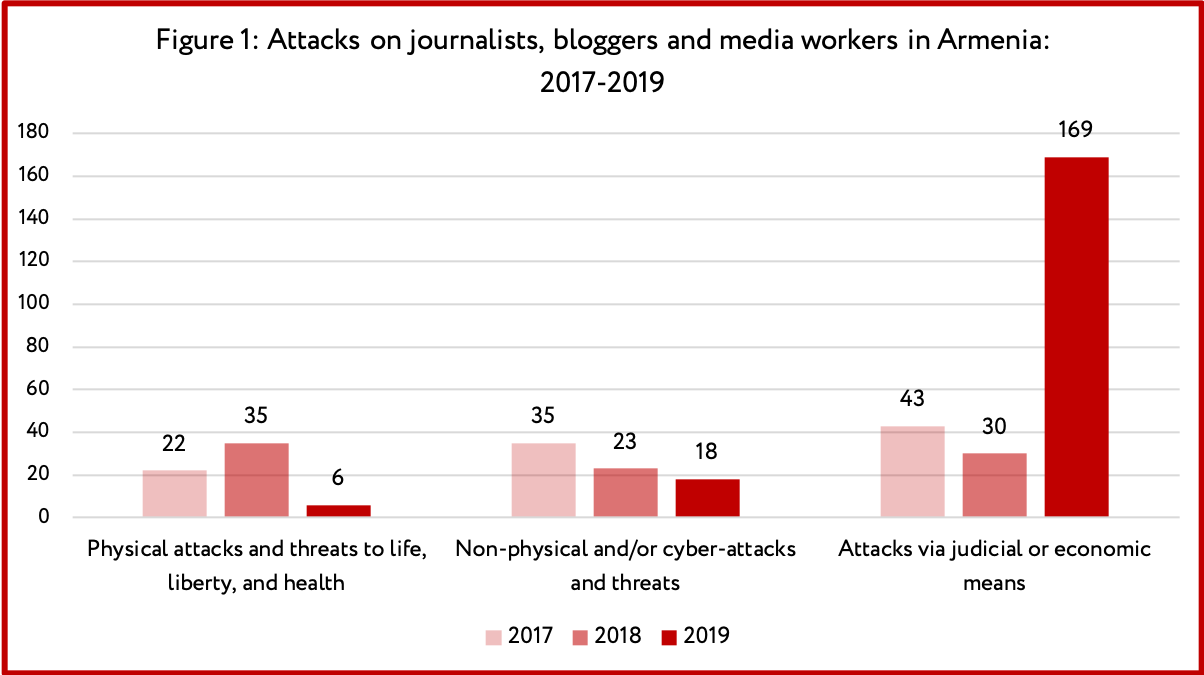

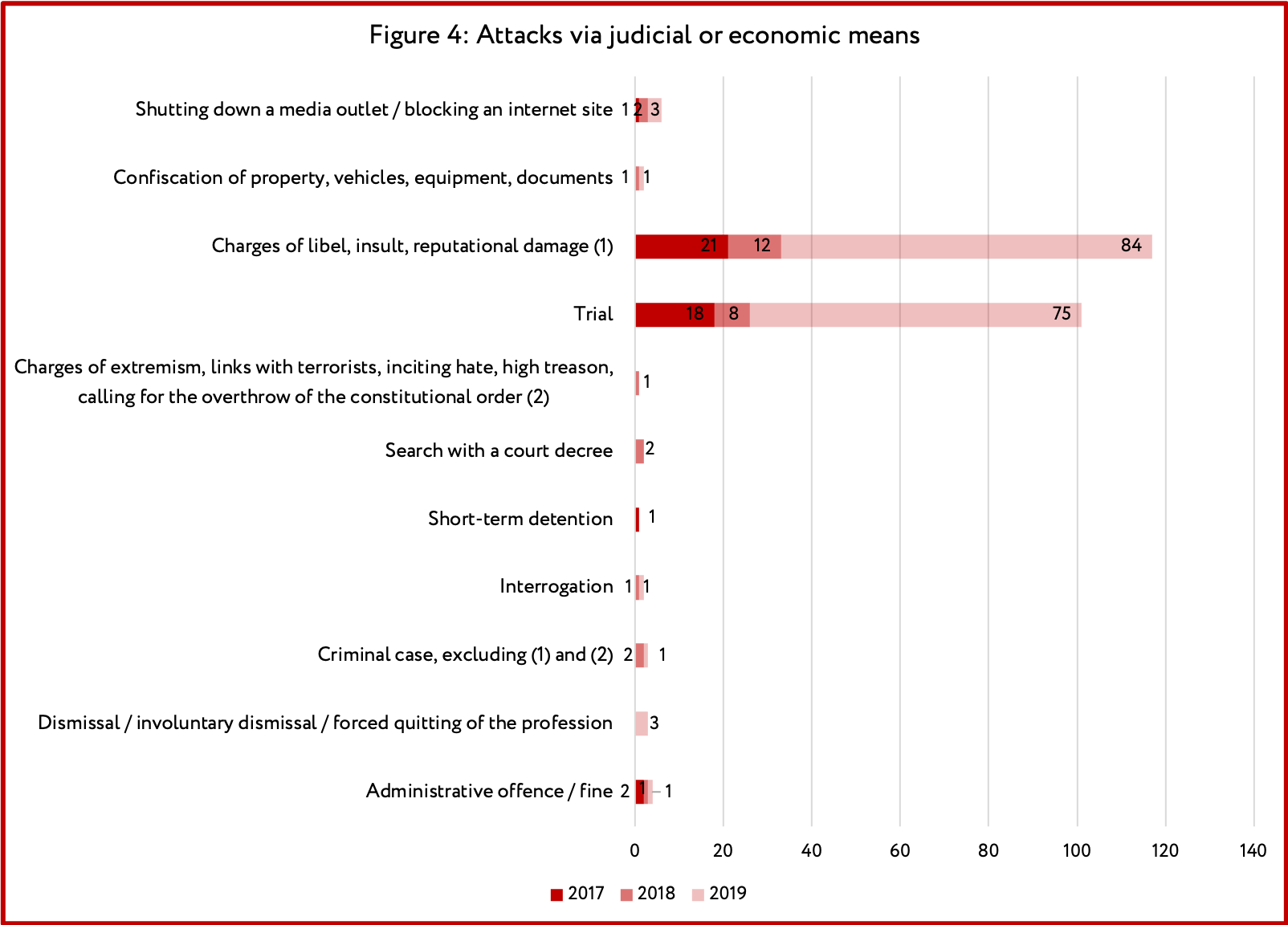

Reflected in Figure 1 are the data for each type of attack on journalists and media outlets in 2017-2019. This was a period of serious ordeals for Armenian journalists and media outlets. The general and municipal elections held in 2017 were supposed to ensure that Serzh Sargsyan and the Republican Party headed by him remained in power. In conditions when the ruling power was abusing the advantages of incumbency and was even going so far as to bribe voters, media outlets not under the control of the authorities were actively impeding this process. Journalists were digging up evidence of money being handed out in the campaign headquarters of the ruling party’s candidates, as well as of the use of the levers of power to get the electorate’s votes.

As a result, both physical violence and non-physical methods of influence — harassment, intimidation, threats, and unlawful obstruction of journalistic activity — were used against media workers. Judicial means were used as well — accusations of libel and insult and legal actions.

All three types of attack were used against media workers during the 2018 Velvet Revolution. 23 of the 35 acts of physical violence against journalists and cameramen recorded in 2018 occurred specifically during their coverage of the revolutionary events.

A peculiarity of 2019 in post-revolutionary Armenia became the fact that the acute political struggle between the former regime and the new government flowed over into the social networks and the media. The process of polarisation of the media intensified as a result, as the overwhelming majority of media outlets, serving the interests of their political sponsors and patrons, began to ignore the public interest. Hate speech, fake news, manipulation, insults, and libel began to be actively used in the news space. This led to a never-before-seen flood of lawsuits against journalists and media outlets, which will be discussed in the “Attacks via judicial means” section. Thus, the number of attacks via judicial and/or economic means more than quadrupled from 2017 through 2019.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

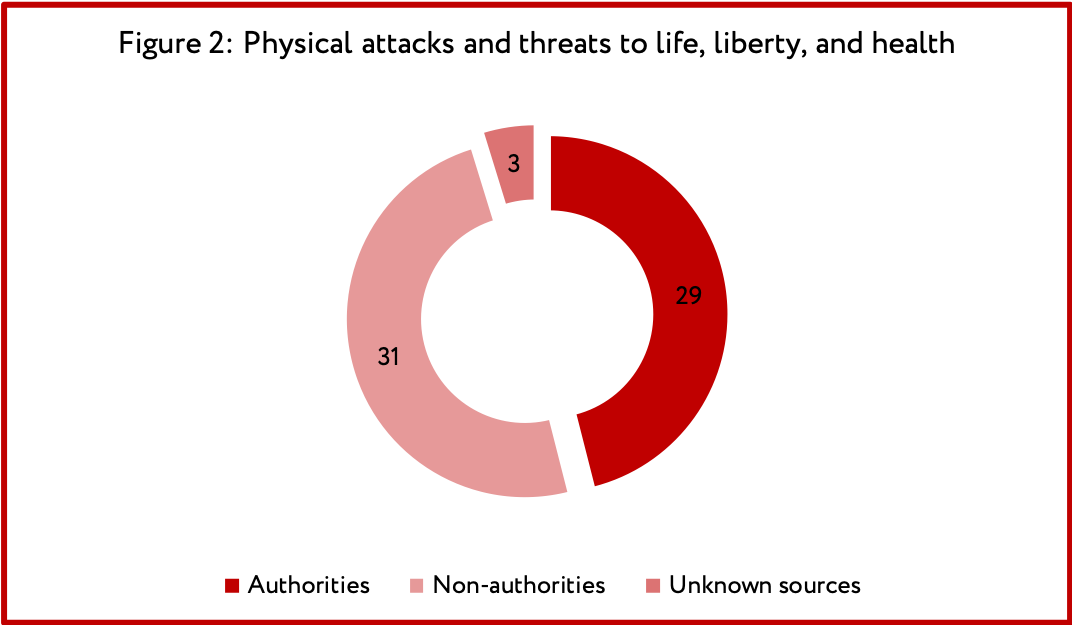

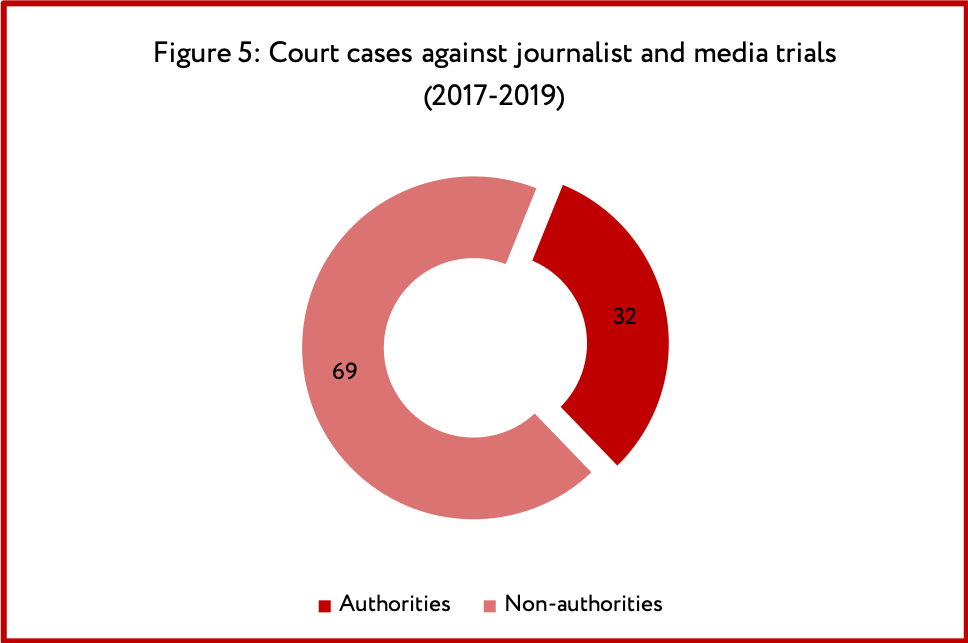

Figure 2 shows the number of physical attacks against media workers in 2017-2019 emanating from representatives of the authorities, not from representatives of the authorities, and from unidentified assailants.

Physical violence in relation to journalists became a widespread phenomenon in the course of the 2017 elections and reached a peak during the time of the Velvet Revolution protest actions. Of the 22 recorded incidents of physical attacks against media employees in 2017, 11 were committed whilst they were covering the election campaigns and the actual elections to the National Assembly of the RA and Yerevan’s Council of Elders. 7 of the 22 assaults were carried out by representatives of the authorities.

- In March 2017, during a live broadcast from the street, police employees impeded the work of journalist Robert Ananyan and cameraman Sevak Mesropyan of the A1 + television company: they were twisting the cameraman’s arms and not letting him shoot video, and then grabbed both television company employees by the throat.

- On the day of the parliamentary elections, April 2, 2017, correspondents Sisak Gabrielyan of Radio Libertyand Shorik Galstyan of the Araratnews.am news website discovered evidence of bribery of voters by representatives of the campaign staff of one of the ruling party’s candidates. This sparked off physical aggression: the reporters were pushed, telephones were grabbed from their hands, and Sisak Gabrielyan was injured, while one of the female voters pulled Galstyan by the hair.

Of the 35 instances of physical assaults on journalists and cameramen recorded in 2018, 26 took place in the days of the Velvet Revolution. In 20 of the cases, it was police who were using force. In the remaining cases, the journalists were assaulted by civilians (some wearing masks); as it later emerged, these were thugs in the employ of businessmen with close ties to the regime.

- In April 2018, Alina Sargsyan, a reporter for the CivilNet.am website, was beaten by a policeman whilst she was filming the arrest of demonstrators.

- In April 2018, a masked police employee assaulted Radio Liberty journalist Naira Bulgadaryan on the Square of the Republic in Yerevan, struck her arm and knocked the camera out of her hands, and did not allow her to continue the video shoot. It could be seen in the live broadcast how policemen were running, while the journalist’s camera was falling during the recording. During a preliminary investigation into the criminal case by the Investigative Committee, a decision was adopted to recognise Naira Bulgadaryan as a victim.

- During a video shoot of protest actions, Public Radio of Armenia producer Vruyr Tadevosyan was assaulted by a group of people wearing civilian clothing and masks. They grabbed his tablet and mobile phone, beat him up with clubs, and smashed his car. A criminal case was initiated, but after a year it was closed “due to insufficient evidence” and no one was punished.

After the victory of the Velvet Revolution and the cessation of the protest actions, the number of physical attacks against journalists declined markedly. In 2019 there were only six recorded, and not one of the assaults was associated with actions by the police or other representatives of the authorities.

- In March 2019, television presenter Hamlet Ghushchyan declared in an interview with the Hraparaknewspaper that he had been abducted. Ghushchyan recounted that some time back, people working for a well-known businessman had abducted him, “drove me someplace at night … and put a pistol to my forehead.”

- In December 2019, several dozen inhabitants of the village of Ovtashen in Ararat Oblast assaulted a film crew from the Kentron television company consisting of journalist Artur Akopyan and cameraman Simik Maiilyan, punching them and damaging a video camera. The film crew managed to save part of the video recording of the incident, thereby corroborating that the attack took place.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

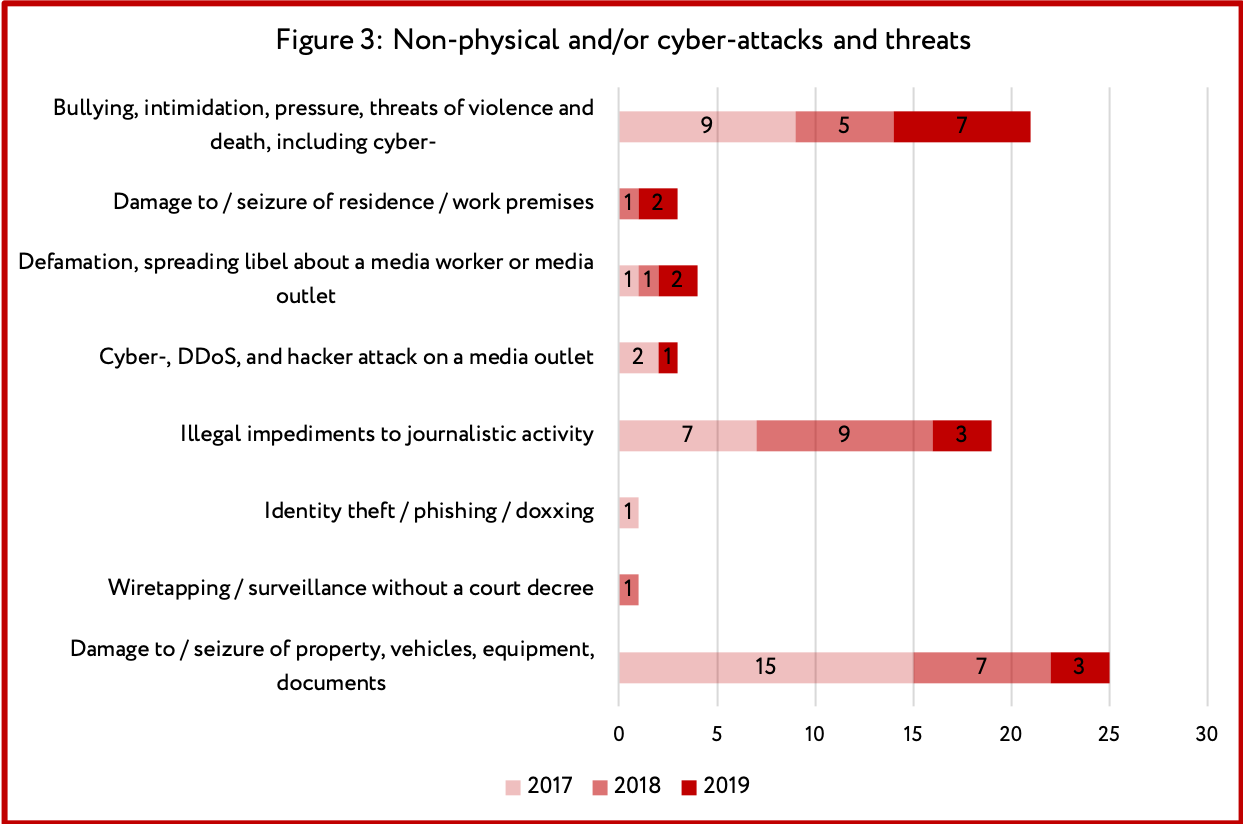

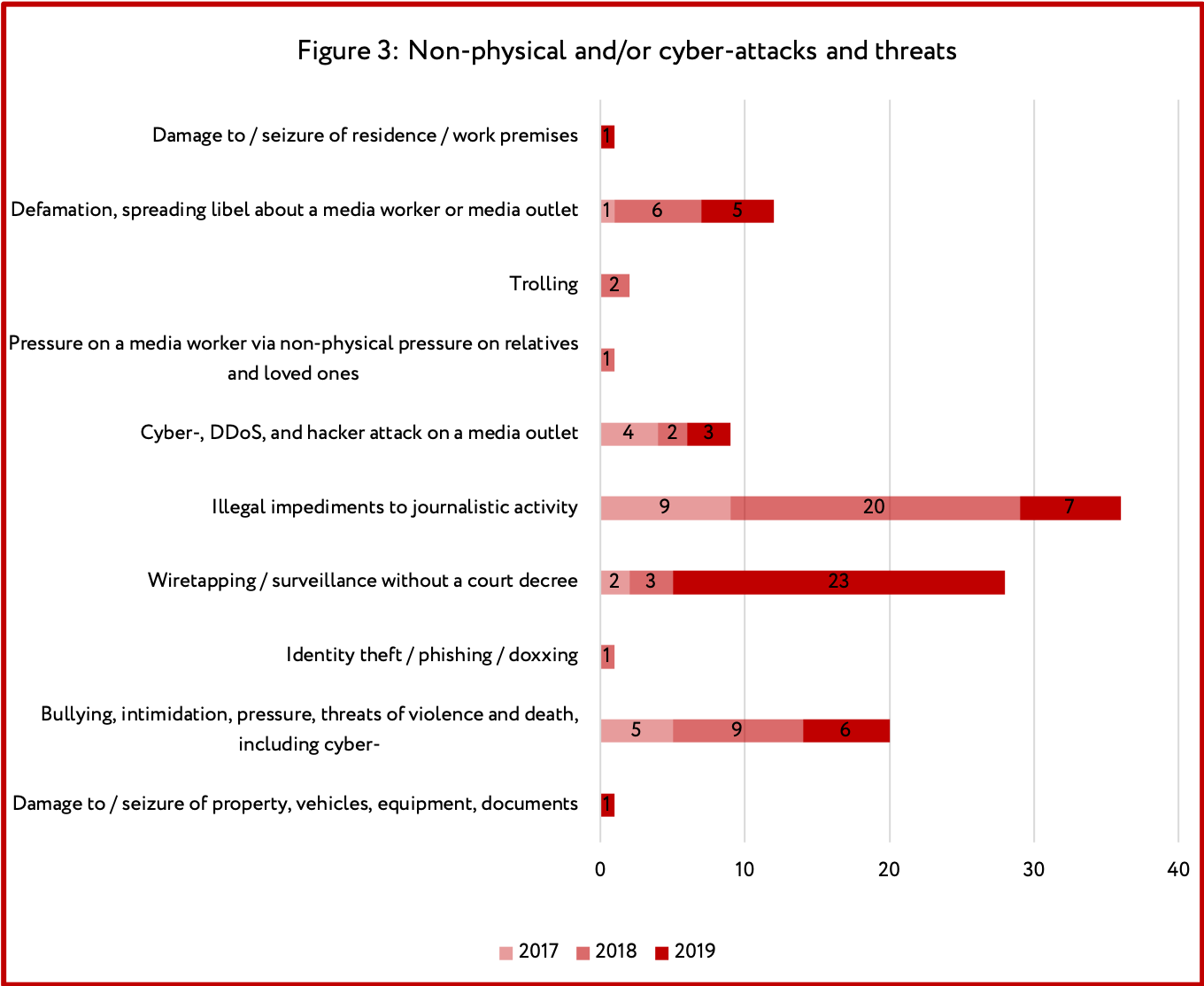

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the predominant methods of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats that were recorded in 2017-2019. Between 2017 and 2019 the number of attacks in this category halved, from 35 to 18.

The three most common methods of non-physical attacks on media workers in Armenia were damage to/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, or documents; harassment, intimidation, pressure, and threats of violence and death, including cyber-; and unlawful obstruction of journalistic activity.

- In April 2017, on the day of the parliamentary elections, the Aravot.am news website was subjected to DDoS attacks resulting in serious disruption of its service.

- In January 2018, the editorial staff of the Medialab.am news website received serious threats from a Facebook user. He insinuated that Medialab.am might suffer the same fate as the French magazine Charlie Hebdo, which had become the victim of a terrorist attack in January 2015.

- In May 2019, a car belonging to the editorial staff of the Syunyants yerkir newspaper was torched in Kapan. Samvel Alexanyan, the newspaper’s editor, believes the motivation behind the arson was revenge.

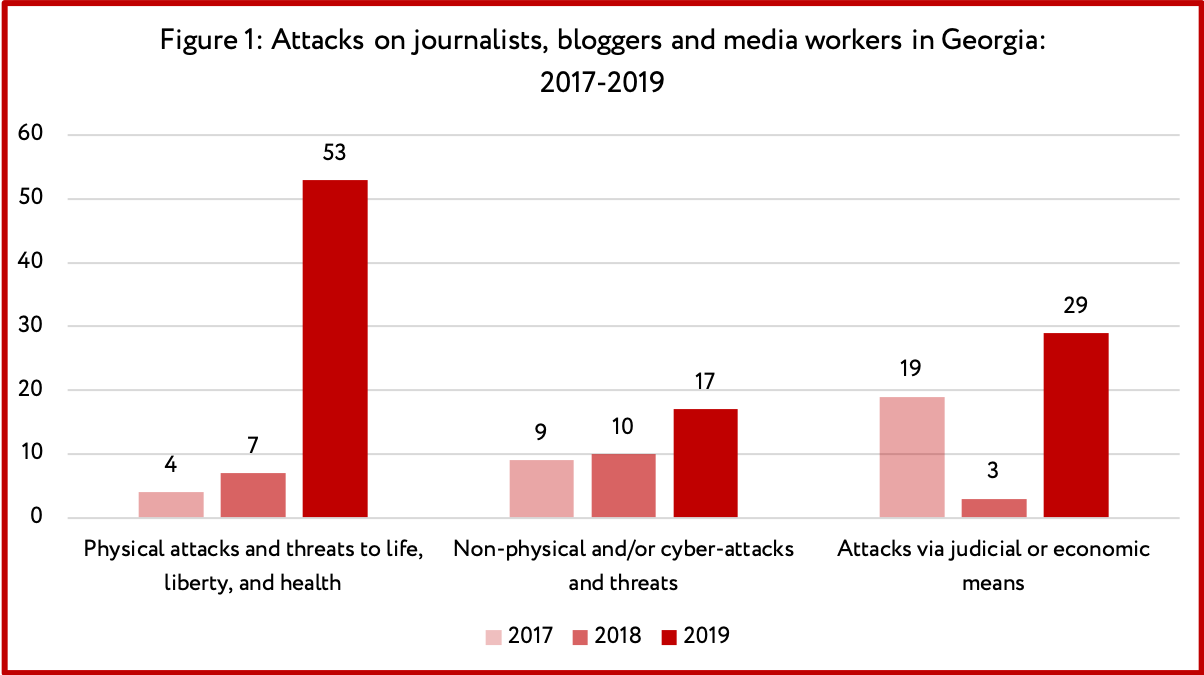

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL OR ECONOMIC MEANS

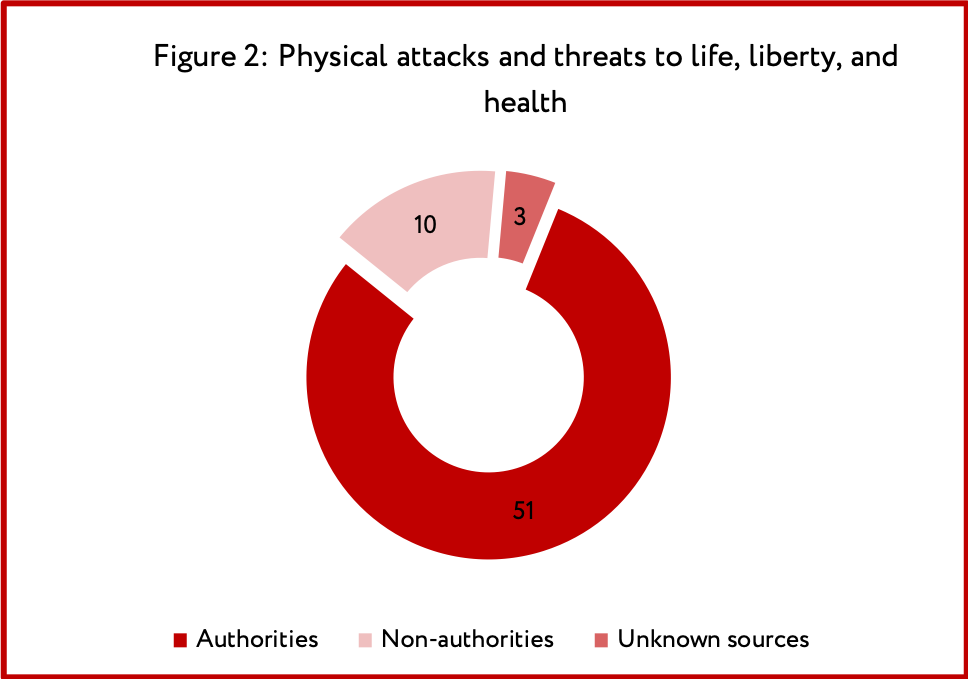

Against the background of a decline in attacks of a physical and non-physical nature in 2019, there was a sharp increase in the frequency of court actions brought against journalists and the media on charges of libel, insult, and reputational damage: there were 84 such incidents (compared to 21 in 2017). Not all of the cases made it to trial, however. In 2019, courts agreed to hear and began trial proceedings with respect to 85 new claims, which is 2.5 times more than in the two previous years combined.

It is noteworthy that during the period covered in this study, nearly 70 percent of the lawsuits against journalists and the media were filed not by representatives of the authorities, but by ordinary citizens representing various strata of society (Figure 5).

- In October 2017, Versandik Akopyan, a former MP and the owner of the Yerevan Champagne Wines Factory, filed a claim with a court of general jurisdiction against OOO Editorial Board of the Zhogovurd Newspaper, the founder of the Armlur.am news website, demanding the retraction of what in his opinion was libellous information.

- In June 2018, Samvel Harutyunyan, the head of the State Committee for Science under the Ministry of Education and Science of the RA, filed suit in the Yerevan City Court of General Jurisdiction against Daniel Ioannisyan, programme coordinator for the Union of Informed Citizens civic organisation, requesting indemnification of 2 million drams for harm inflicted to honour and dignity.

- In May 2019, Andrei Gukasyan, governor of Lori Oblast, filed a claim against MIG television company journalist Karina Vanesyan, demanding an apology for an insult.

The unprecedented increase in the number of trials against media workers in Armenia over the past three years is driven by two circumstances. First, after the decriminalisation of libel and insult, many people have begun to regard the new Article 1087.1 of the Civil Code of the RA, which prescribes culpability, including material liability, for these violations, as a convenient means for settling scores with undesirable media and their employees. Second, as has already been noted, in the post-revolution period, when the acute political struggle between the former regime and the new shifted from the streets to the media, expressions of hate, lies, insults, and libel became widespread in publications. Those named in such publications began to turn to the courts more frequently for recourse in defending their honour and dignity.

Georgia

1/ KEY FINDINGS

151 instances of attacks/threats against professional and citizen media workers and the editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Georgia were identified and analysed during the course of the study. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Georgian, and English languages using the method of content analysis. Data obtained by the expert interview method were likewise used in the report. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 3.

- Not a single incident of murder of journalists has been recorded in Georgia in the past 11 years. After the 2008 war with Russia there have been no incidents that might be interpreted as attempted murder; however, both assaults on journalists whilst they are carrying out professional duties and attempts to impede their work have been frequent.

- A troubling symptom is pressure by government structures on the media, which has intensified many-fold. This is associated with political activism in society and the desire of Georgia’s authorities to suppress opposition sentiments and restrict the political activism of parties and civic movements. Only a few years ago, no more than 10-15 incidents per year of pressure on journalists were being recorded.

- A distinctive feature of the Georgian media landscape is that only 26 of the 154 recorded incidents took place outside the capital, and a further 12 were recorded in other countries, while the rest all occurred in Tbilisi. Leading among the regions in terms of the number of violations of journalists’ rights are the Adjaran autonomy, Imereti, and Samegrelo.

- 12 incidents have been recorded of violations of the rights of Georgian journalists beyond Georgia’s borders: ten in Ukraine and two in Turkey. An incident with Turkish border guards was settled. In Ukraine, deportation of Georgian journalists or banning their entry to the country are linked with the situation surrounding ex-president Mikheil Saakashvili; not a single such incident was protested or heard in court.

- Cyber-crimes, including attacks on websites, have not reached a threatening level in Georgia; however, the use by the authorities of such methods as creation of fake websites and social media accounts in order to influence the public has become a problem.

2/ THE MEDIA IN GEORGIA

Georgia is the only country in the post-Soviet space apart from the Baltic countries where the obligations of the state in the realm of freedom of speech are spelled out in the Constitution. Article 24 states: “The state or individual persons shall not have the right to monopolise the mass information media or the means of disseminating information”. In connection with this, there are no state-run media in Georgia apart from the parliamentary journal. The Criminal Code of Georgia has likewise been decriminalised and does not permit the persecution of journalists for their professional activities.

There is not a single state agency in Georgia that would exercise oversight over the media or regulate the media; the country has no institution that provides accreditation for foreign journalists. Registration of a media outlet is no different than registration of entrepreneurial activity and takes several minutes to complete. There are provisions for incentives for the development of a media business and for a tax exemption in the event of low profitability.

It is impossible to give a precise number for how many newspapers and magazines are being published. In Tbilisi alone, more than 150 newspapers and magazines have been on sale in recent years, although the majority of them did not survive the competition and ceased operations. A further 50 or so print media were being published outside the capital; most of them have closed or remain only in the form of news websites.

The National Commission for Communications of Georgia offers a more precise number for the operations of television companies and radio stations: in 2018, applications for frequency allocation were submitted by 57 radio stations and 102 television channels. The number of news websites is not subject to accounting inasmuch as they do not get registered in Georgia.

There is no state-run television in Georgia. The only channel that receives state funding is the Public Broadcasting First Channel, the former state channel in Soviet times.

According to a National Democratic Institute survey, the ratings of television channels in December 2019 look as follows: Imedi – 30%; Mtavari Arkhi – 18%; Rustavi-2 – 12%; and TV Pirveli – 5%; the rest are below three percent, and many are below 1%. Among foreign television channels, the television channels of Azerbaijan (3%) and Armenia (1%) enjoy relative popularity.

Georgia ranks 60th out of 180 countries of the world in terms of the level of freedom of the press according to the data of the Reporters Without Borders NGO’s annual World Press Freedom Index.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

Figure 1 offers a general analysis of attacks on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in Georgia from 2017 through 2019. It can be noticed that the numbers of attacks in all three categories has increased since 2017, despite the large decline in attacks via judicial and/or economic means in 2018. Significantly, the greatest increase took place in the category of physical attacks; moreover, in 46 of the 53 incidents recorded in 2019, the journalists had suffered at the hands of policemen.

The rise in aggression against journalists on the part of the authorities can be explained in part by the increased political activism both of parties and of society as a whole: 2019 was the last year before the October 2020 parliamentary elections. Opinion polls taken by the International Republican Institute (IRI) and the National Democratic Institute (NDI) in mid-2019 indicated a drop in the ratings of the ruling Georgian Dream party, which seemed unlikely to hold on to the constitutional majority in parliament that it had had in 2012 and 2016. In order to retain influence over voters, Georgian Dream began to persecute popular television channels with an opposition orientation.

The increasing pressure on journalists became a troubling trend. The authorities are attempting to intimidate the media via judicial and financial means, as well as through the direct use of violence.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

Incidents of physical violence against journalists can be divided into two groups:

- Assaults committed by persons not directly linked with the authorities, for example the security guards of private enterprises or ideological supporters of the regime.

- Targeted actions by the police against journalists who are carrying out their professional duties.

- In January 2017, during a siege of the Rustavi-2 television company, the pro-regime and pro-Russian organisation Georgian March committed an assault on general director Nika (Nikoloz) Gvaramia and other journalists.

- The only instance of abduction is associated with the disappearance of the Azerbaijani independent journalist Əfqan Muxtarlı on May 29, 2017. Based on the statements made by human rights organisations, not only Azerbaijan’s special services, but those of Georgia as well, had taken part in his abduction.

- The greatest number of reporters, camera operators, and other media workers (39 persons) received injuries on the night of June 21, 2019, when a protest action was broken up by special forces of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia. Tear gas and rubber bullets, including banned ones, were used in dispersing the crowd.

- On June 21, 2019, police employees detained and beat Niko Mukhigulashvili, a journalist with the First Channel, and seized and broke the camera of a cameraman from the same channel.

All remaining instances of physical pressure (22) are associated with assaults on journalists whilst they were performing their professional duties, or are linked with their work.

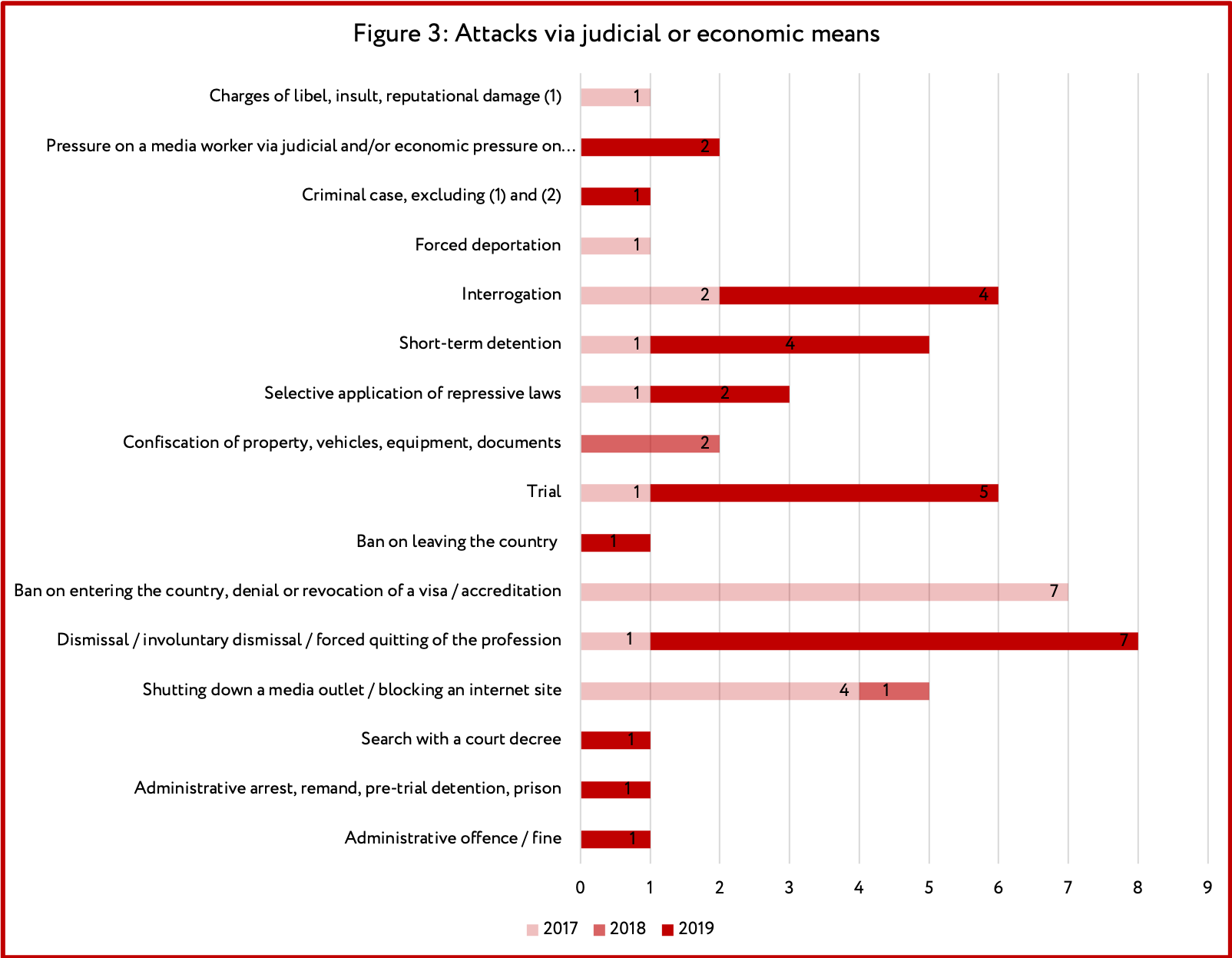

5/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL OR ECONOMIC MEANS

All the incidents of attacks against journalists and media editorial offices via judicial and/or economic means that were recorded in the three years (51 in total) originated from representatives of the authorities.

During the period covered in this study, the top three mechanisms of pressure on journalists included:

- Dismissal/involuntary dismissal/forced quitting of the profession.

One incident was recorded in 2017 and seven in 2019; moreover, the majority of the incidents are linked to an editorial staff shakeup at the Rustavi-2 television company and the remaining three with a change of management at the Adjara TV television channel in April 2019.

- Ban on entering the country.

In 2017, Georgian journalists were denied entry onto the territory of Ukraine.

- Short-term detentions by the police.

In 2019, four incidents were recorded of short-term detention of journalists by the police, and moreover with the use of force.

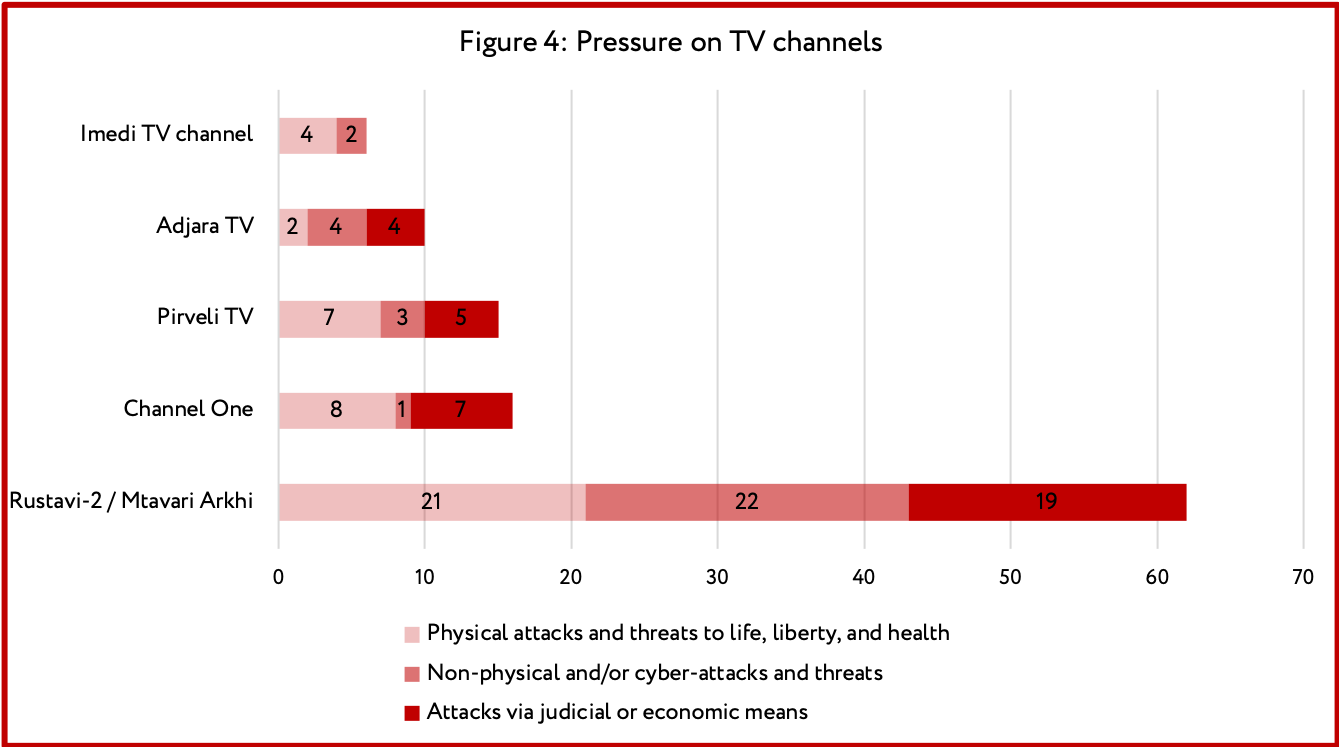

6/ PRESSURE ON TELEVISION CHANNELS

According to ratings, before September 2019 there were two main television channels in the country — Imedi and Rustavi-2: they are watched by 72-76% of the country’s population. The former sympathises with the ruling party, Georgian Dream, and the second with the opposition.

As the parliamentary elections approached, Georgia’s authorities launched several attacks on Rustavi-2. Not only were physical attacks such as assaults on journalists undertaken, but judicial ones as well, with selective application of laws. The ruling party’s main objective was to replace the owners of Rustavi-2 and to reorient the channel from critique of the authorities to neutral coverage of events. After the authorities had achieved their aims, the journalists who left Rustavi-2 created a new channel, Mtavari Arkhi, which began on-air operations on September 9, 2019.

Other popular TV channels such as Pirveli TV were also harassed by the authorities, which successfully secured a change in the management of Adjara TV, the public television company of the Adjara Autonomous Region.

Other popular channels too were subjected to persecution on the part of the authorities: Pirveli TV, as well as the Public Television of the Adjarian Autonomy, Adjara TV, where the authorities managed to replace the management.

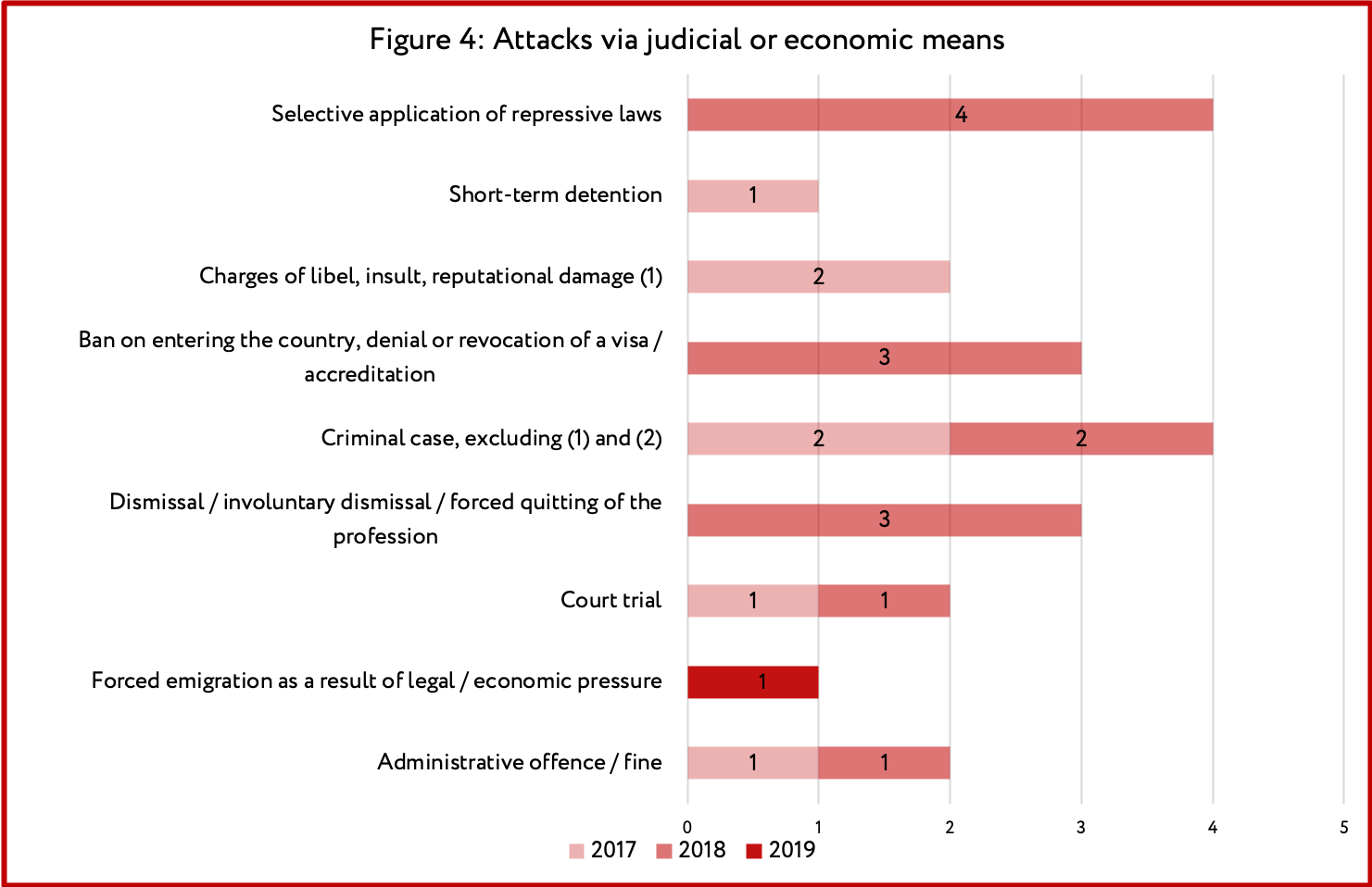

Figure 4 shows the level of pressure exerted on television channels popular in the country. The privileged position of the pro-regime Imedi channel is obvious. The high level of violence against television journalists was associated above all with police actions during the dispersal of protesters on the night of June 21, 2019.

Moldova

1/ KEY FINDINGS

160 instances of attacks/threats against professional and civilian media workers and the editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Moldova were identified and analysed during the course of the study. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Romanian, and English languages using the method of content analysis. Data obtained by the expert interview method were likewise used in the report. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 4.

- The greatest number of instances of physical attacks and/or threats to life, liberty, and health (16) was recorded in 2019; 12 of these incidents occurred on June 8 and 9, 2019, during a political crisis in the country.

- The main sources of the attacks/threats against media workers were representatives of central and local/regional bodies of power, including state officials, politicians, civil servants, and local councillors.

- There is a direct correlation between political events in the country, intensification of protests, and the number of attacks/threats against media workers. Thus, the peak moments of the political crises in recent years – August 2018 (especially August 26, 2018) and June 2019 (especially June 8 and 9, 2019) — were the most dangerous times for journalistic activity in Moldova.

- During the period covered in this study, the most frequent forms of intimidation and persecution of Moldova’s media workers were non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats.

- The most widespread methods of non-physical attacks/threats were illegal impediments to journalistic activity, wiretapping, surveillance without a court decree, harassment, intimidation, pressure, and threats of violence and death, including cyber-.

It should be noted that some attacks and threats do not become known to the public and are not reflected in the media because many journalists consider that attacks in the virtual space and non-physical threats are an unavoidable part of their everyday professional activity and therefore do not report them.

2/ THE MEDIA IN MOLDOVA

Moldova holds 91st place out of 180 in the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index rating. For comparison, in 2013 the country was in 55th place.

According to the data of the state television and radio broadcasting regulator, the Council for Television and Radio, at the end of 2019 there were 60 television channels and 55 radio stations in the country. According to the data of the National Statistical Bureau, 126 newspapers with an overall annual circulation of 40 million copies were published in Moldova in 2018, along with 205 magazines and other periodical publications with an overall annual circulation of 1.5 million copies. There are no official statistics about the number of news portals and websites.

According to a public opinion poll conducted in December 2019 by the Barometer of Public Opinion, the most reputable sources of information for the inhabitants of Moldova are television (49% of respondents) and the internet (34%). Radio holds third place with 5%. On the whole, Moldovan media enjoy the trust of around 60% of the respondents.

Vladimir Plahotniuc’s media holding company was dominating Moldova’s media market beginning in 2015. His Democratic Party of Moldova was in power, in coalition with other parties or by itself, until June 2019. This holding company, according to different data, included from 8 to 11 television channels and radio stations, as well as a multitude of websites and portals. This media holding company lost its influence after the Democratic Party lost power in June 2019. Concurrently, the media group affiliated with the Party of Socialists of Moldova, which is controlled by the country’s president Igor Dodon, gained a very strong foothold.

A substantial portion of media institutions is owned by politicians, either directly or through placemen, while their editorial policy is dependent on the political and business interests of their owners. The advertising market is likewise controlled by business groups affiliated with the regime. These politico-economic factors are responsible for the unstable situation of the independent media outlets in the country. Their advertising incomes are not great and unpredictable, forcing them to rely on grants for their survival.

Local and foreign media experts consider the concentration of ownership in the media sphere and the lack of editorial independence to be the main problems facing the media in Moldova.

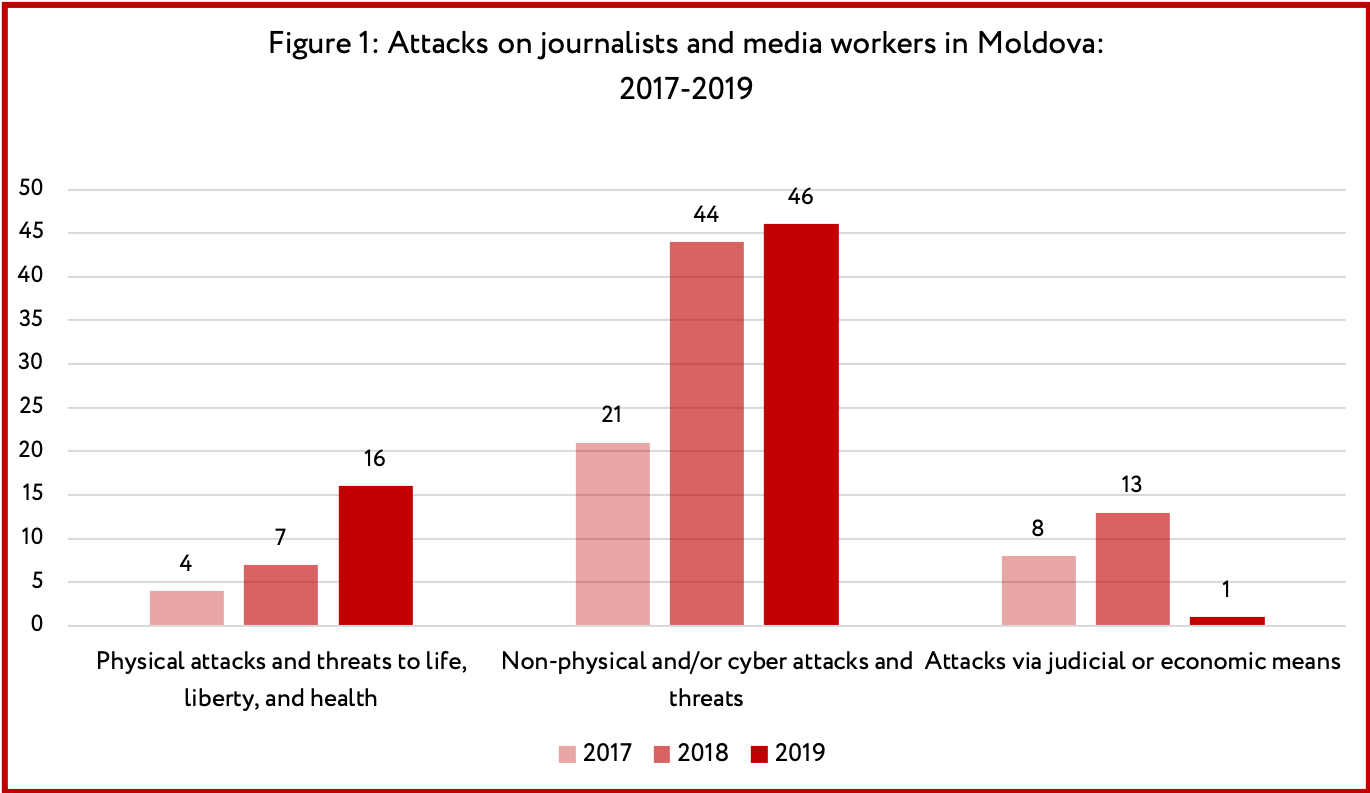

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

Figure 1 presents summarised data on the above-named three main types of attacks/threats against media workers in Moldova for the 2017 – 2019 period. There were a total of 160 instances of attacks/threats recorded during the three years; moreover, the number of attacks against journalists almost doubled in the three years.

Most often used to intimidate inconvenient journalists and editorial offices were non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats, including defamation campaigns, harassment, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence, bullying in social networks, and cloning of web pages.

All 16 physical assaults on media workers in 2019 were recorded in June, when journalists covering political events and protest actions in the capital were hurt during the political standoff in the country.

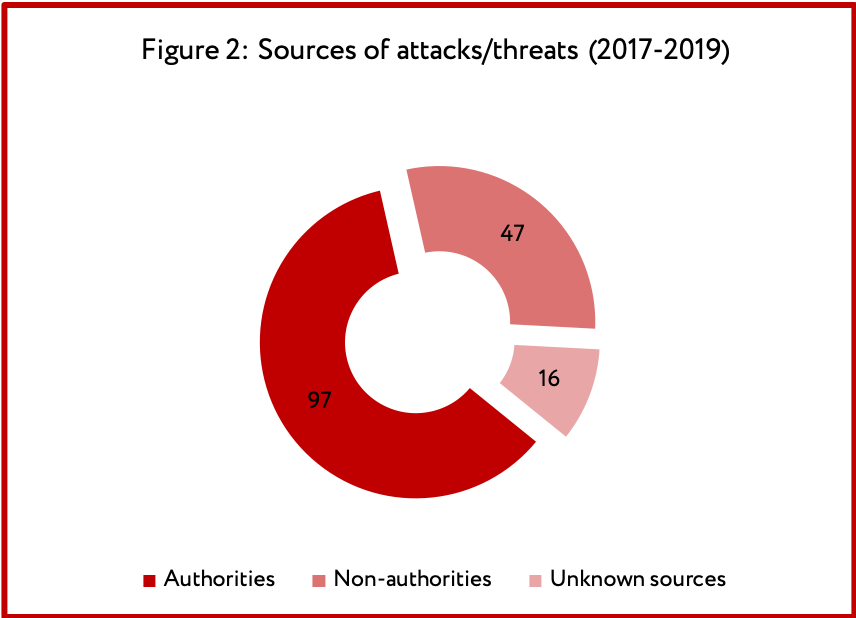

In 60% of the incidents, the attacks and threats in relation to the media workers came from state officials, other persons holding public posts at the central and local/regional level, policemen, or state security guard services or private security company workers, who were impeding journalists in the performance of their professional duties, in some cases resorting to violence (Figure 2). In 10% of the incidents, it was not possible to establish from whom the threat was emanating. However, for a number of such incidents there is evidence that the attacks against the media workers were being undertaken at the instruction of politicians or state officials.

During the period covered in this study, the greatest number of attacks was recorded against the Ziarul de Gardă newspaper (29 incidents) and the Jurnal TV (19 incidents) and TV8 (18 incidents) television channels.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

The number of physical attacks on media workers in Moldova quadrupled during the period covered in this study, from 4 incidents in 2017 to 16 in 2019. For the most part, journalists were subjected to non-fatal attacks and beatings. One incident of attempted murder was recorded nonetheless.

- In February 2019, BTV television channel cameraman Eugen Gumeniuc was nearly run over by a ruling party candidate’s automobile. At this moment Gumeniuc was doing a video shoot of pre-election agitational materials hanging from the city hall building. The footage recorded how the automobile was approaching the BTV television channel employee in order to run him down.

On August 26, 2018, when protest actions against the ruling Democratic Party were taking place in Chișinău, several cases of physical attacks against journalists covering the protests were registered:

- Radio Free Europe radio station reporters Nicu Guşan and Tatiana Iaţco and Unimedia.info portal journalist Aurica Rusnac-Jardan were pushed by bodyguards of the Şor party leaders as they were trying to get interviews.

In June 2019, when the Democratic Party organised pickets outside a number of state institutions during a political crisis in the country, journalists were subjected to a multitude of attacks, both on the part of the authorities and on the part of the protestors. The following incidents were among those that were recorded:

- Protestors assaulted TV8 reporter Sergiu Niculiţă, cameraman Oleg Cozlov, and journalist Daniela Cuţu, damaging professional equipment. Cuţu was likewise drenched with water.

- Unimedia.info portal journalist Mihaela Dicusar was subjected to physical assault on the part of state guard and security service employees as she was attempting to put questions to leaders of the Democratic Party.

- Aliona Ciurcă, a reporter for the Ziarul de Gardă newspaper, was subjected to attack on the part of politician Vlad Plahotniuc’s bodyguards.

- Ecaterina Alexandr, another reporter for the Ziarul de Gardă newspaper, was assaulted by a female participant as she attempted to take a photo. The woman grabbed the camera and struck the lens.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

Non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats are the most widespread form of pressure on journalists in Moldova — they account for more than 60% of incidents. The top three methods of attacks in this category include (see Figure 3): illegal impediments to journalistic activity, surveillance without a court decree, harassment, intimidation, pressure, and threats of violence and death, including cyber-.

The editorial offices where the largest number of incidents of illegally impeding journalistic activity were registered in this period were Ziarul de Gardă (no fewer than 19 incidents), TV8 (no fewer than 13 incidents), and JurnalTV (no fewer than 12 incidents).

- In 2017, the Action and Solidarity party restricted access to its congress for a team from the Prime TV television channel, which the party was accusing of twisting facts.

- In 2017, the presidential administration of the Republic of Moldova banned photocorrespondent Constantin Grigoriţă from working at its events.

- In 2018, the ruling Democratic Party banned TV8 and Jurnal TV teams from participating in weekly press briefings because the editorial policy of these television channels did not suit the ruling party.

- These same two television channels, as well as correspondents for the Ziarul de Gardă newspaper, were repeatedly banned from participating in press conferences and other events of the Şor Party.

- In 2019, journalist Vadim Ungureanu was denied access to events conducted by the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Another widespread method of non-physical attacks/threats is tapping telephone conversations and illegal surveillance of media workers, primarily for the purpose of intimidation.

- In June 2019 the RISE Moldova portal published an investigative report on illegal phone-tapping of the conversations of a number of politicians, activists, and journalists.

- In November 2019, the chairman of the parliamentary Commission for National Security, Defence and Public Order published a list of individuals, including many media workers, whose phones had been illegally tapped.

A record number of coordinated cyber-campaigns against influential journalists with the aim of intimidating and smearing them were conducted in 2018. The attacks and threats were often initiated by politicians who found certain journalistic materials unacceptable. Among the victims were Natalia Morari (TV8), Alina Radu (Ziarul de Gardă), Cornelia Cozonac and Mariana Colun (Anticorupție.md), Liuba Şevciuc (RISE Moldova) and journalists from the Nokta.md and Nordnews.md portals.

- In July 2018, Ilan Şor, primar [mayor] of the Orhei municipality and leader of the Şor Party, posted a video in the social networks that insulted journalists and contained threats to their life and health.

- In December 2018, MP Oleg Savva attacked Anticorupție.md portal investigative journalist Marianna Colun in the social networks, stooping to obscenities and insults.

Besides that, in the 2017-2019 period several online media outlets were subjected to DDoS attacks and/or “cloning” (the creation of similar websites with fake content). The Zdg.md, Deschide.md, Stopfals.md, Reporterdegarda.md and Newsmaker.md portals were subjected to cloning.

6/ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL OR ECONOMIC MEANS

21 incidents of attacks via judicial and/or economic means were recorded in the period from 2017 through 2019 – 13% of the overall total (see Figure 4).

Judicial and/or economic means of pressure on journalists and media workers in Moldova are practically not practiced at all. The following incidents can be mentioned:

- In May 2017, a criminal case was initiated against the journalist and activist Nicolae Josan for a fight with another journalist.

- In October 2017, editor of the Pravda Pridnevstrovia newspaper Nadezhda Bondarenko was fined for libel in the Transnistria region after she had reported about an accident involving a female relative of an official from the unrecognised Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (Transnistria).

- In May 2018, a driver who was delivering a print-run of the Cuvântul weekly newspaper from the town of Rezina was detained short-term. An administrative offence case was opened against him.

- In August 2018, an administrative offence case was opened against journalist Victor Sofroni after information he had passed on to the police turned out to be false.

- On November 5, 2018 journalist Vadim Ungureanu was given a suspended sentence of three years of deprivation of liberty and fined in an amount of 70,000 lei for “active corruption”.

Three instances of involuntary dismissal of journalists were recorded in this period:

- In June 2018, journalist Dumitru Pelin was forced to resign from the TV Nord television channel after he had posted a video recording from a protest action on another website.

- In October 2018, Alina Panco, a news presenter on the 10TV television channel, was dismissed for publication of news about an MEP’s reaction to the extradition of seven educators from Moldova to Turkey. Despite being directed by management not to publish this news, the team released the material on the air.

- In October 2018, the entire staff of the 10TV television channel announced its resignation as a sign of solidarity with Alina Panco. Presenter Anatol Ursu clarified that for the previous two weeks the channel’s management had been dictating to the journalists how they should write on certain subjects, but that the television channel’s employees had ignored these instructions.

Several instances were likewise recorded of foreign journalists, in particular from the Russian Federation, being banned entry to the country. A complete list of incidents is presented on the Media Risk Map on the Justice for Journalists Foundation website.

ANNEX 1: ATTACK TYPES, IDENTIFIED BY JFJ FOUNDATION

Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health

- Abduction, taking captivity/hostage, illegal deprivation of liberty

- Attempted murder

- Beating / injury / torture resulting in death

- Death while in custody or as a result of loss of health in captivity

- Disappearance

- Fatal accident

- Murder

- Non-fatal accident

- Non-fatal attack / beating / injury / torture

- Pressure on a media worker via physical pressure on relatives and loved ones

- Punitive psychiatric treatment not resulting in death

- Punitive psychiatric treatment resulting in death

- Sexual harassment

- Sexual violence

- Sudden unexplained death

- Suicide

- Suicide attempt

- Unlawful military conscription

Non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats

- Breaking into email / social media accounts / computer / smartphone

- Bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber-

- Cyber-, DDOS, and hacker attack on a media outlet

- Damage to/ seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents

- Damage to/seizure of the residence / work premises

- Defamation, spreading libel about a media worker or media outlet

- Identity theft / phishing / doxxing

- Illegal impediments to journalistic activity

- Pressure on a media worker via non-physical pressure on relatives and loved ones

- Pressure on a source, including threats of violence and death

- Trolling

- Wiretapping / surveillance without a court decree

Attacks via judicial or economic means

- Administrative arrest, remand, pre-trial detention, prison

- Administrative offence / fine

- Arrest of bank account

- Authorised travel ban (movement inside a country or specific region / town)

- Ban on engaging in journalistic activity

- Ban on entering the country, denial or revocation of a visa/accreditation

- Ban on leaving the country

- Charges of extremism, links with terrorists, inciting hate, high treason, calling for the overthrow of the constitutional order (2)

- Charges of libel, insult, reputational damage (1)

- Confiscation of property, vehicles, equipment, documents

- Court trial

- Criminal case, excluding (1) and (2)

- Dismissal / involuntary dismissal /forced quitting of the profession

- Forced deportation

- Forced emigration as a result of legal / economic pressure

- House arrest

- Interrogation

- Pressure on a media worker via judicial and/or economic means on relatives and loved ones

- Search with a court decree

- Search without a court decree

- Selective application of repressive laws

- Short-term detention

- Shutting down a media outlet / blocking an internet site / request to remove or block the article

- Suspended sentence

- Unauthorised travel ban (inside country, region or town)

- Wiretapping/ surveillance with a court decree

ANNEX 2: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (ARMENIA)

- Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression – a civic organisation operating in Armenia, engaged in studying the situation in the realm of freedom of speech and publishing periodic reports, as well as defending the rights of journalists and media outlets.

- Yerevan Press Club – an NGO, the principal goal of which is support and development of free, independent, and quality media.

- Media Initiatives Center – an Armenian NGO, the main mission of which is to create and disseminate free and independent content and by means of this to promote the all-encompassing and harmonious development of society.

- Hetq.am– the internet publication of the Armenian civic organisation Investigative Journalists.

- Freedom House – an international human rights NGO that evaluates and publishes reports on the level of freedom in 210 countries and territories worldwide, including on freedom of speech and media activity.

- Reporters Without Borders – an international NGO whose aim is to protect journalists who are being subjected to persecution for doing their job.

- The Committee to Protect Journalists – an international organisation engaged in defending the rights of journalists.

- DataLex.am – the database of Armenia’s judicial system.

- Region research center – an Armenian civic organisation that studies the regional problems of the South Caucasus, including those concerning media activity.

- Haykakan zhamanak [Armenian Times] – a daily newspaper.

- Factor.am – an Armenian multimedia news portal.

- Radio Azatutyun – the Armenian service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

ANNEX 3: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (GEORGIA)

- Gruziya Online – a news agency about events in Georgia, in the Russian language.

- On.ge – a news website about events in Georgia and the Caucasus, in the Georgian language.

- Media.ge – a news and analysis website, a project of the Internews-Georgia organisation — a media portal in the Georgian, Russian, and English languages.

- Civil.ge – a news and analysis website, a project of the UNO Association of Georgia, in the Georgian, Russian, and English languages.

- Caucasian Knot – a news and analysis website about events in the Caucasus, in the Russian language.

- Sova – an online magazine about the politics, economy, and life of Georgian society in the Russian language.

- Radio Tavisupleba – the website of Radio Liberty’s Georgian service, in the Georgian language.

- Formula TV – a news television channel, in the Georgian language.

- Detals.net – a news portal about events in Georgia and the surrounding region, in the Russian language.

- IPN – a news website about events in Georgia, in the Georgian, English, and Russian languages.

- Tabula – a news and analysis website about the politics and economy of Georgia, in the Georgian language.

- Novosti Gruziya – a news website about events in Georgia, in the Russian language.

- Newsreport.ge – a news website about events in Georgia, in the Georgian language.

- Batumelebi – a newspaper and website with news about events in the Autonomous Republic of Adjara and Georgia, in the Georgian language.

- Mtavari Arkhi – a television channel, in the Georgian language.

- First Channel – the news website of the Public Broadcasting of Georgia television channel, in the Georgian and Russian languages.

- Netgazeti.ge – a news and analysis website about events in Georgia, in the Georgian language.

- Adjara TV – the news website of Public Television Broadcasting of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, in the Georgian language.

- Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics – the website of an NGO engaged in problems of ethics in the work of the media and journalists, in the Georgian and English languages.

- Radio Pirveli – the website of the radio station of the same name, in the Georgian language.

- Caucasian Echo – the website of a project of Radio Liberty’s Georgian Service, in the Russian language.

- GHN – a news and analysis website about events in Georgia and the world, in the Georgian, English, and Russian languages.

ANNEX 4: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (MOLDOVA)

- Moldovan Press Status Index 2017 Report

- Moldovan Press Status Index 2017 Report

- Moldovan Press Status Index 2017 Report

- Radiography of attacks against non-governmental organizations from the Republic of Moldova (September 2016 – December 2017)

- Radiography of attacks against non-governmental organizations from the Republic of Moldova in 2018

- Ziarul de Gardă – a newspaper in the Romanian language in electronic and print format.

- Jurnal.md – a Republic of Moldova television channel.

- Unimedia.info – a news website.

- 1news – a Republic of Moldova news portal.

- Agora.md – a news portal about events in the country and abroad.

- Publica.md – a news website.

- RISE Moldova – an NGO which includes investigative journalists and activists from Moldova and Romania.

- Nokta.md – an internet-media portal. The goal of the project consists of increasing the level of transparency of the authorities and accessibility to information significant for society.

- nordnews.md – a news website.

- Bloknot – a news website.

- anticoruptie.md – an online platform in the Republic of Moldova, for identifying cases of corruption and similar offences.

- TV8 – a television channel.

- NewsMaker – an independent online publication.