AUTHOR OF THE REPORT: KHALED AGHALY, LAWYER AND SPECIALIST IN MEDIA LAW IN AZERBAIJAN

PHOTO: Arqument.az

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Azerbaijan, 159 incidents of attacks/threats against media professionals and citizen journalists, editorial offices of traditional and online publications, and online activists were identified and analysed in the course of the research for 2022. Data for the study were collected using open-source content analysis in Russian, Azerbaijani and English. In addition, information about these attacks was obtained from media reports, stories from journalists and bloggers, as well as statements from lawyers providing legal assistance to journalists. A list of the main sources is provided in Annex 1.

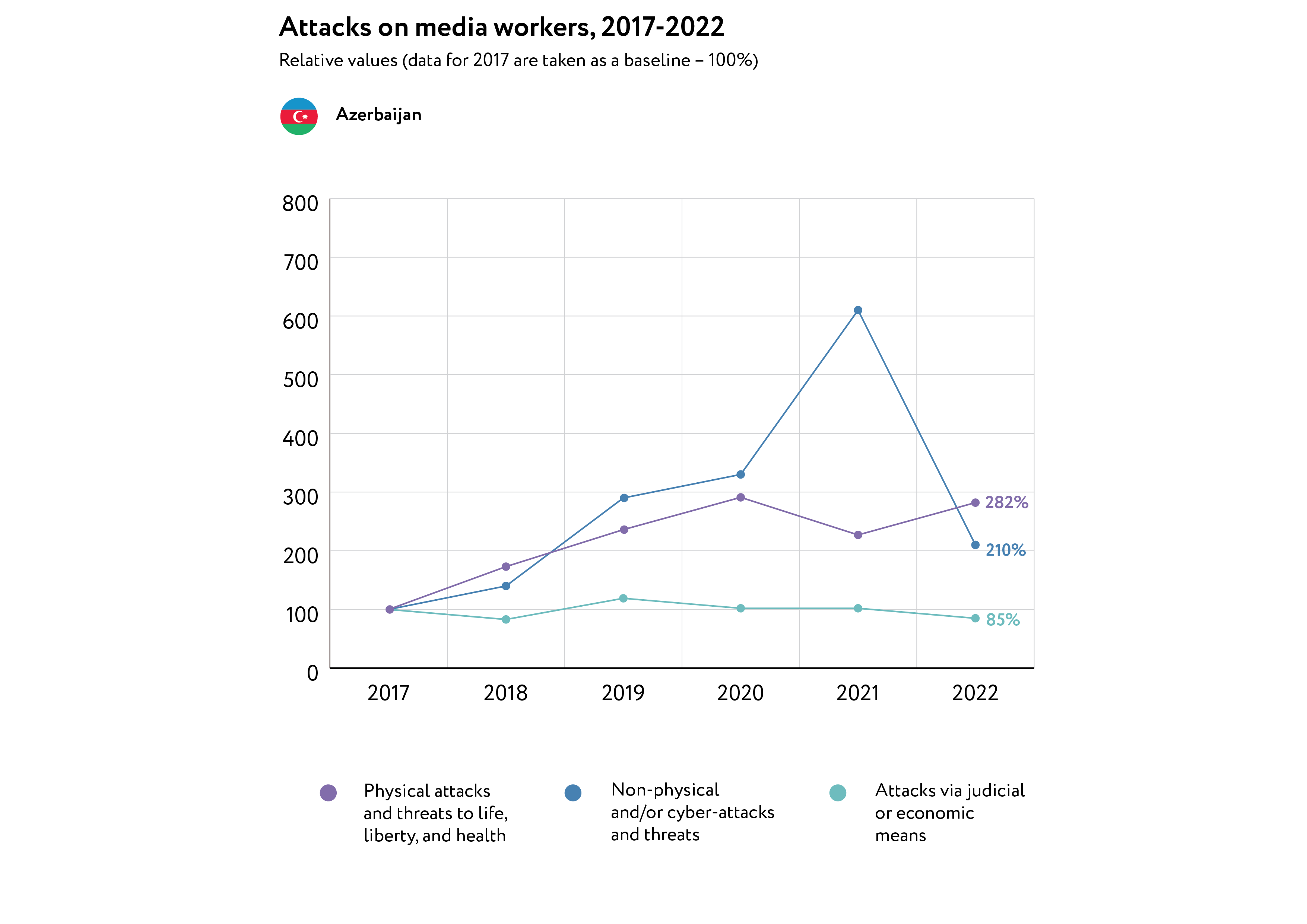

- In 2022, there was a decrease in the total number of attacks against media workers. In 2020, 194 incidents were recorded. This number rose to 215 in 2021 before falling to 159 in 2022.

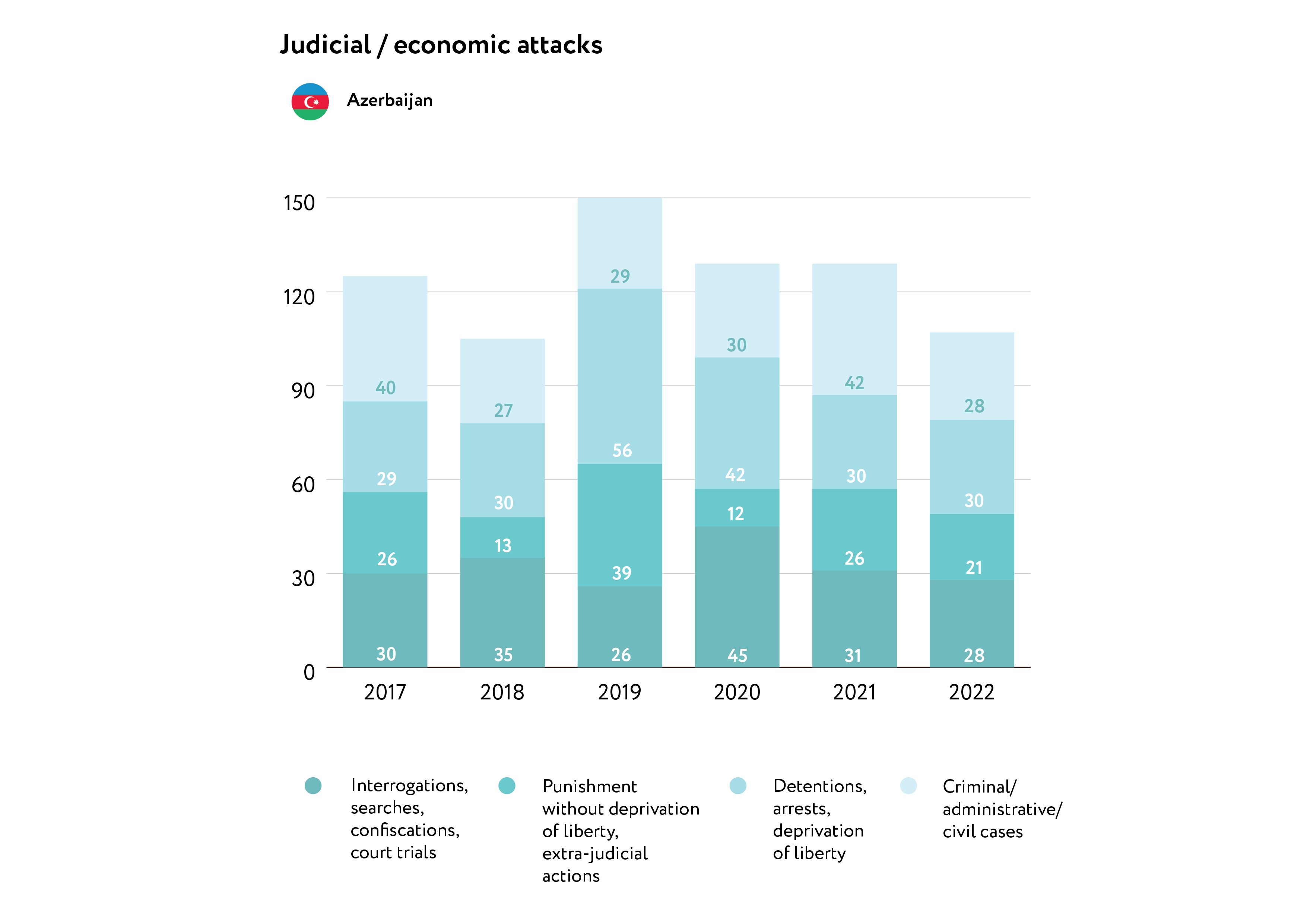

- The most common type of pressure media representatives faced in Azerbaijan was attacks via judicial and/or economic means (107 incidents).

- The number of incidents related to non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats has decreased threefold since 2021.

- Attacks against journalists and media outlets continue to go uninvestigated. Over the course of 2022, none of the people responsible for the attacks have been identified or brought to justice.

- Attacks against Azerbaijani media workers living abroad continued. In 2022, at least two incidents of both physical and non-physical attacks on journalists were recorded.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN AZERBAIJAN

Reporters Without Borders’ annual report revealed a slight change in Azerbaijan’s position, having ranked 154th out of 180 in their Press Freedom Index in 2022. According to the non-governmental organisation, virtually the entire media sector is under the control of the authorities, whose primary aim is to clamp down on independent media. Most independent news sites, such as Azadliq and Meydan TV, which have been subjected to government censorship, are based abroad.

In Freedom House’s 2022 Internet Freedom Report, Azerbaijan scored 38 points. In 2023, the country scored 37. Countries scoring between 10 and 39 points are considered “not free”. Internet freedom in the country remains limited. Freedom House reported that “authorities continued to manipulate the online information landscape, blocking numerous independent and opposition websites”.

In 2022, the main event impacting the media landscape in Azerbaijan was the enactment of the new media law (“The Media Law”). Following its enactment, previous media laws adopted in 2021 and then adapted to the standards of the Council of Europe (“On the Mass Media” and “On Television and Radio Broadcasting”) were abolished. The new law changed all existing rules regarding the media and facilitated the creation of a single, state-controlled register of media outlets and journalists. Only media outlets and journalists included on the register can engage in “legal” journalistic activity. This law significantly restricts the field of independent journalists’ work. For example, they will not be able to take advantage of opportunities such as accreditation.

The new law transferred all media regulation to a single centralised media agency, which was established by the government at the beginning of 2021. The agency is also working to create a register of media websites and journalists. According to official data, about 6,000 media outlets are registered in Azerbaijan, only about 200 of which were included on the media register.

The European Commission for Democracy argued that this type of law should not be applied in any country that holds membership to the Council of Europe, as Azerbaijan does. A resolution adopted in December 2022 by the Council of Europe’s ministers requires the Azerbaijani government to amend this law.

The trends negatively impacting media workers included:

- There are no legal means to protect journalists and press freedom in Azerbaijan. During the year, none of the dozens of complaints about illegal actions against media workers were addressed.

- The legislation regarding criminal liability for defamation remains unchanged. As was the case in recent years, these laws are strictly enforced, severely restricting the media and journalists and forcing them to engage in self-censorship.

- Journalists are persecuted using administrative legislation, which is open to significant arbitrary interpretation and abuse. In 2022, dozens of such incidents were recorded.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

In 2022, 150 attacks against journalists, bloggers and other media workers were recorded in Azerbaijan. Compared to 2021, the number of recorded attacks decreased by 150%.

Attacks via judicial and/or economic means remained the main method of exerting pressure on media workers in Azerbaijan. The country witnessed a decrease in the number of non-physical and cyber-attacks. There were 61 such incidents recorded in 2021 but only 21 in 2022. Instances of physical pressure on journalists increased. In the majority of cases, these attacks occurred while journalists were covering protests.

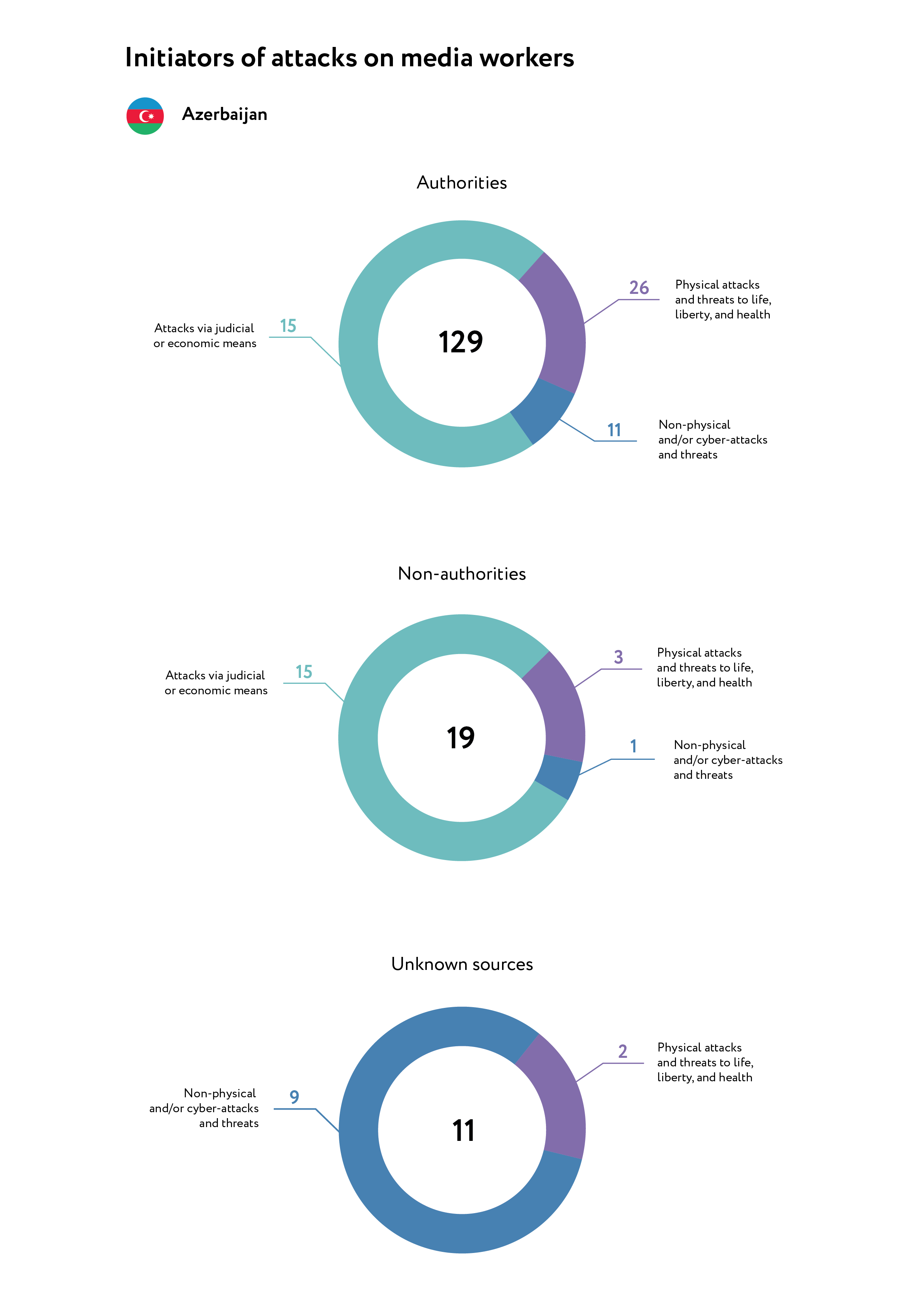

In 81% of cases, government officials were responsible for the attacks; in 13% of cases, attacks were committed by individuals who were not representatives of the authorities.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

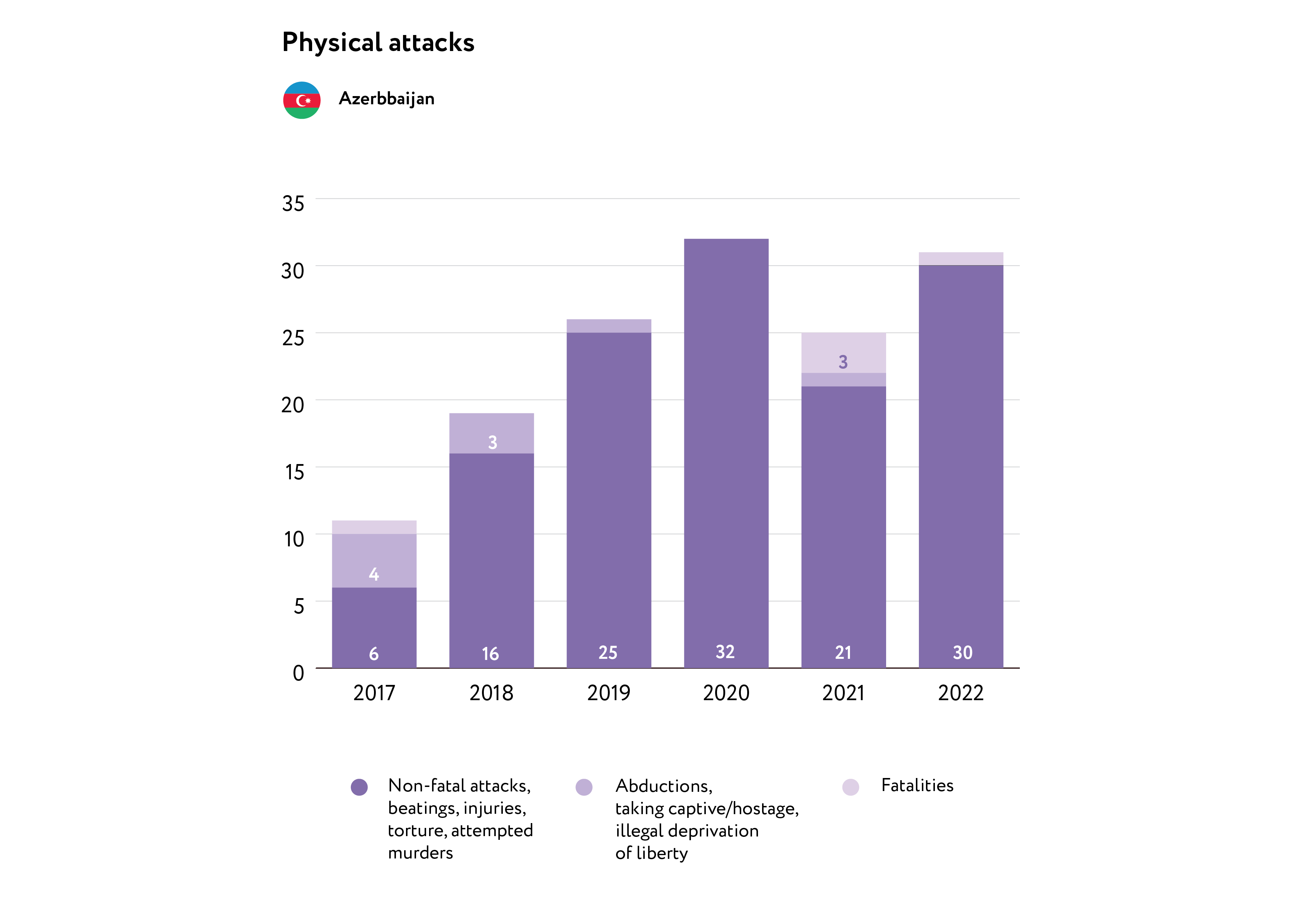

In 2022, 31 physical attacks against media workers were recorded in Azerbaijan. Most of these incidents occurred while journalists were collecting information about large-scale events, protests or running live broadcasts. All but one of these incidents were non-lethal.

In 2022, one journalist was killed:

- On 22 February, at approximately 16:00, freelance journalist Avaz Shikhmammadov (Hafizli) was murdered in a suburb of the capital Baku. A joint statement issued by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Prosecutor General’s Office suggested that the murder was committed by his cousin, Amrulla Gyulaliev, who was apparently intoxicated at the time and who admitted that he committed the crime due to a sense of personal animosity towards Shikhmammadov. On 29 July 2022, courts found Amrullu Gyulaliev guilty under Article 120.1 (“premeditated murder”) and sentenced him to 9.5 years in prison.

Additionally, one incident was recorded involving an attack on an Azerbaijani blogger living abroad:

- On 21 November, Azerbaijani blogger Orkhan Agayev was beaten outside his apartment in Berlin. The blogger believes that the attack was ordered by the Azerbaijani authorities and reported that his attackers spoke Azerbaijani. “I was coming home and saw a man approaching me,” Agayev said. “He punched me, and I fell to the ground. Having knocked me to the ground, he called [in Azerbaijani] another person to come over. They both started beating me: they kicked me, then they leaned on me and started punching me in the head. It felt like they were hitting me with some kind of heavy object, not just their fists. I saw one of them holding a knife. I shouted and called for the police. If my wife had not gone out onto the balcony and begun screaming and filming it, they probably would have killed me”.

There were at least 19 recorded incidents involving physical violence by police officers and other government officials (such as presidential security guards) committed during journalists’ coverage of protests. It is worth noting that these physical attacks were also often accompanied by non-physical attacks, namely, damage or seizure of property and professional equipment:

- On 7 January, journalists Alekper Azaev and Amina Mammadova, who were collecting information during a protest held by social activist Giyas Ibrahimov in front of the Presidential Administration building, were harassed by police officers and security guards.

- On 9 January, Meydan TV journalist Sevinj Vagifgizi was obstructed by police officers while collecting material for a report in the centre of Baku. The officers in question cited new media laws to justify the move and stated that there were restrictions on the rights of journalists to collect information.

- On 15 February, Radio Azadliq journalist Fatima Movlamli was beaten in a police station in the Sabail district of Baku. Fatima Movlamli and Azel. TV journalist Sevinj Sadigova were violently detained while covering a protest in front of the Presidential Administration building before being taken to the police station. “We were detained, they tried to take away our phones and demanded that we delete the footage,” said Movlamli. “The police sergeants, right in front of their superiors, knocked me to the ground twice and started kicking me. I have shoe marks on my feet. They tore my jacket”. Among those detained was journalist Teymur Kerimov, who later reported that he had suffered an injury to his hand after an “interaction with the police”.

- On 8 March, an employee of the Voice of America radio station, Turkan Bashirova, was arrested during a protest in the centre of Baku. The journalist says she was assaulted by police officers. During the same protest, Ismail Tagiyev, an employee of the news portal Abzas.org, was also subjected to ill-treatment.

- On 1 August, activist Zümrüd Yağmur staged a picket in front of the Presidential Administration building. Journalists collecting information on the protests — Aitaj Akhmedova (Meydan TV), Fatima Movlamli (Turan TV) and freelance journalist Nargiz Absalyamova were subjected to physical violence by guards. The journalists were forced to stop broadcasting after security officials tried to take away their phones.

- On 27 April, two journalists, Kanal13.TV employee Gunel Guliyeva and Azad Söz employee Vusalya Hajiyeva were assaulted during a protest in front of the Presidential Administration building organised by workers who had not received their wages. The journalists were arrested and subjected to physical intimidation, and their footage was deleted.

- On 11 November, the opposition Musavat party and the Popular Front Party of Azerbaijan both held protests. Journalists preparing reports from the protests (during which more than 150 opposition figures and activists were detained) were subject to pressure and were not allowed to film. Aysel Umudova, an employee of Meydan TV, was assaulted and suffered a leg injury despite wearing a press vest. Meydan TV employee Khayala Agayeva was also attacked. Her phone was taken from her and broken. Independent journalist Nargiz Absalamova was assaulted, and her phone was taken away and smashed on the ground.

- On 15 November, members of the opposition Musavat party attempted to hold a protest in front of the Iranian Embassy in Azerbaijan. Dozens of protesters were detained. A group of journalists covering the protest were dealt with violently by police officers dispersing the protesters. Amongst those abused by the police were freelance journalists Dilara Mirieva and Elnara Gasimova, Meydan TV employees Aysel Umudova and Aytaj Tapdig, and Azadlyq newspaper reporter Fatima Movlamli.

Other incidents recorded in 2022 include:

- On 8 June, Toplum TV correspondents Vusala Mikail and Nurai Jamal were subjected to ill-treatment while working in the Yasamal district of Baku. The journalists, who had witnessed the forced evictions of shops near the Academy of Sciences metro station, were filming events as they unfolded. An individual who identified himself as a representative of the executive power of the Yasamal region offered the journalists a bribe to stop filming. They rejected the offer. Vusala Mikail’s phone was stolen, and the perpetrator fled the scene. The phone was returned to her later that day.

- On 8 May, at about midnight, Ayten Mammadova, a human rights journalist working with Radio Azadliq, was attacked at the entrance of her home. She claims that a middle-aged man followed her into the elevator. Holding a knife to the journalist’s throat, he threatened her, citing an unspecified court case, demanding that she not cover it. “When the elevator door closed, he grabbed me with one hand and put a knife to my throat with the other,” Mamedova said. “The knife cut against my throat. Then he put the knife away before putting it to my throat again. I was left with a cut on my neck. He told me: ‘You haven’t got a clue.’ Then, he began to threaten my young daughter. When the elevator got to my floor, he let me out.”

- On 4 April, Gulmira Aslanova, the wife of the convicted journalist and editor-in-chief of Xeberman.com, Polad Aslanov, held a protest in front of the Penitentiary Service building, objecting to the assault of her husband in a prison colony by a fellow cellmate. “His face was swollen, there were fingernail marks on his cheeks and throat,” Aslanova said. “This prisoner reacts to anything Polad does, demanding that he ‘not talk or laugh’. The head of the prison confirmed the incident had taken place and said that the prisoner in question had been punished.” Aslanova is convinced that the incident was a deliberate provocation. “This is not the first time Polad has been assaulted in the prison”, she noted, demanding that the violence against her husband be investigated.

- On 27 April, two journalists, Kanal13.TV employee Gunel Guliyeva and Azad Söz employee Vusalya Hajiyeva, were assaulted during a protest in front of the Presidential Administration building staged by workers who had not received their wages. The journalists were detained, and the footage was deleted.

- On 12 September, Toplum TV channel employee Farid Ismailov was prevented from reporting during a briefing held at the Ministry of Defence. The journalist was forcibly removed from the hall without any explanation. Allegedly, the order to remove Ismailov from the hall came from senior ministers.

- On 2 December, Elmar Aziz, an employee of the news portal Arqument.az, was taken to the Pirallahi district police station. Prior to this, he shared a video on social media of traffic police officers taking bribes. The journalist said that at the police station, he was treated rudely and threatened.

- On 14 December, Meydan TV employees Aitaj Tapdig and Khayala Agayeva and independent journalist Teymur Karimov arrived at a protest near Shusha-Khankendi to film, but were detained by “individuals in civilian clothes and black masks”. Agayeva explained that the journalists were not given any explanation but were simply forced into a car and returned to Baku. The journalists reported that during the arrest, their video cameras were taken away and the footage was deleted.

- On 23 December, it was revealed that Abid Gafarov, an activist and host of the KİM.TV YouTube channel, who had been sentenced to a year in prison, had a near-death experience at the Medical Institution of the Penitentiary Service. His wife, Elnura Gafarova, reported the information to the Turan news agency. According to her, at first, doctors thought that he had died, but then he was placed in intensive care, where he eventually regained consciousness. “He doesn’t remember any of this, the doctors told him about everything,” his wife said. Despite having a high temperature, Abid was kept in prison for 10 days, and his requests to be transferred to a medical facility were ignored.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

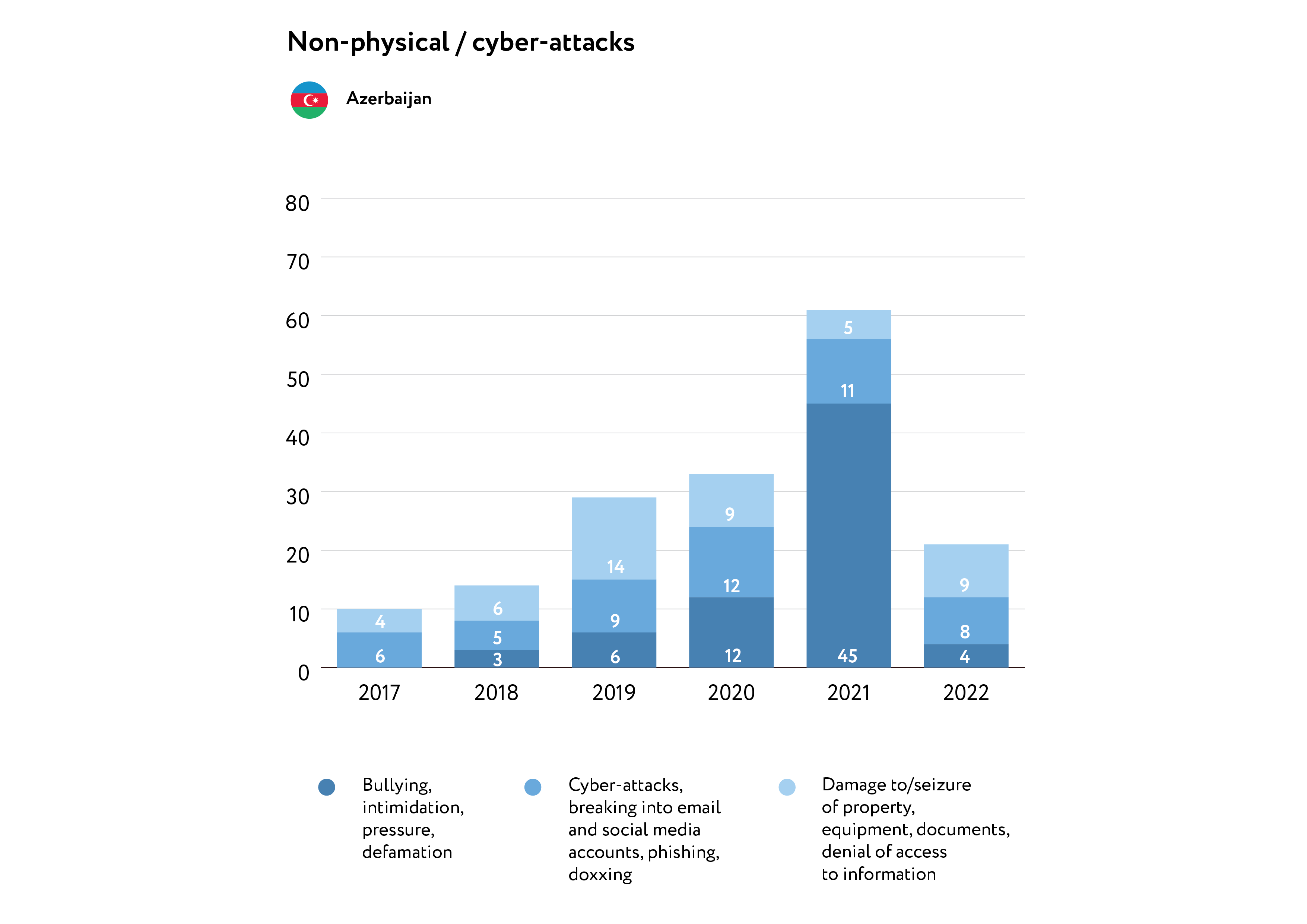

In 2022, there were at least 21 incidents of the editors of Azerbaijani online publications, journalists, and bloggers encountering violence of a non-physical nature, both online and in person. The main targets of these attacks were independent and opposition media and journalists. Compared to 2021, the number of recorded incidents has decreased by three times.

The main methods of non-physical pressure were cyber-attacks and hacking, as well as denial of service attacks (8 incidents):

- On 4 August, the PR manager of the online Baku TV channel, Sadan Huseynova reported that the outlet’s Facebook account had been blocked. “This was a cyber-attack aimed at preventing us from posting information,” Huseynova said. “Baku TV has repeatedly been subjected to cyber-attacks from Armenia.”

- On 6 June, a cyber-attack was carried out against the Turan TV channel broadcast, originating from abroad. According to a statement by the head of the channel, Ganimat Zaidov, its servers were hacked and various materials were deleted. Specialists managed to restore the server as well as the lost materials. Turan TV was established by employees of the Azadliq newspaper who emigrated from Azerbaijan to Europe.

- On 22 August, the Facebook page of the editor of the news portal Yeniavaz.com and the administrator of several Facebook pages, Rasim Mammadli, was hacked. He managed to restore his profile, but at the same time, the Zəfəran and Qəmiş Facebook pages, which he managed, were also hacked. One of the pages, which had 10,000 subscribers, was deleted. The second could not be restored and is currently being used to promote a government agency. Complaints have been made to the relevant agencies to carry out an investigation.

- On 17 September, the Facebook page of the online news platform Toplum TV was hacked, with the perpetrator gaining access to the account by compromising the personal Facebook profile of one of the publication’s employees. As a result, the news platform lost 26,000 subscribers and two weeks of content. Access to the page was later restored.

Cyber-attacks continued throughout 2022. There has been no new progress in investigations into these cases or in punishing the attackers themselves. Neither complaints to government investigative agencies regarding journalists who were under surveillance during the 2021 Pegasus spyware investigation nor the complaints of journalists and media outlets who were subject to cyber-attacks have been properly investigated. Journalists eventually complained to the European Commission of Human Rights about Pegasus, having exhausted all leads in Azerbaijan.

Complaints made to law enforcement agencies by Toplum TV, which faced cyber-attacks, were not investigated. Government institutions have shown to be inconsistent in their investigations of such complaints. For example, Toplum TV was hacked after one of the founders, Alesker Mammedli, received an SMS message on his phone. In another case, however, the investigation was effective. Complaints from citizens who were subjected to blackmail from people threatening to share images of them accessed on Telegram were swiftly investigated. The administrator of several such Telegram channels was quickly arrested and prosecuted. None of the independent or opposition media outlets or journalists who were victims of cyber-attacks received a response as quick and effective as this.

At least three journalists were subject to threats and harassment:

- On 10 January, it was revealed that the founder and editor of Xeberman.com, Polad Aslanov, had been on a hunger strike while under medical supervision in a prison colony. He is permitted to use the prison telephone on Mondays but is not allowed to contact his family, his wife said. She also discovered that her husband’s cigarettes and water were taken away. This is traditionally done to force people to end a hunger strike.

- On 3 July, the head of the Kanal13.TV online channel Aziz Orujov, received death threats while in the centre of Baku. An unknown person approached the journalist, pointed to his child and suggested that he “be careful” otherwise, his child’s life could be in danger. The person who threatened the journalist was later detained by the police.

- On 11 November, the opposition Musavat party and the Popular Front Party of Azerbaijan held protests. Journalists preparing reports from the protest (during which more than 150 opposition figures and activists were detained) were subject to pressure and were not allowed to film. Authorities insulted Tazakhan Miralami, an employee of the Azadliq newspaper, and tried to provoke him.

Additionally, one incident was recorded involving an attack on an Azerbaijani blogger living abroad:

- On 31 May, Tural Sadygly, a blogger and admin of the Azad Söz channel, who moved from Azerbaijan to Germany, stated that he had received death threats. The journalist is known for his regular live social media broadcasts. On 1 June, Sadygly’s parents tried to stage a protest in front of the Presidential Administration building. His father, Alovsat Sadygly, said the government sent a hitman to Europe. “Tural is telling the truth,” said the blogger’s father. “You need to listen to him, not kill him. Three baseless criminal cases have been opened against him, an international search has been announced, and now they have decided to kill him. I came here to express my anger and protest.”

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

In 2022, there were 107 incidents of attacks against journalists and media outlets via judicial and/or economic means in Azerbaijan. Government officials committed 85% of the attacks. The most common methods of exerting pressure were: arrests, warnings, pre-trial complaints, interrogations, and other extra-procedural actions.

Some of the main problems faced by journalists were: being arrested while they were fulfilling their professional duties, confiscation of professional equipment, and forced deletion of footage. In 2022, 22 such incidents were recorded:

- On 9 January, blogger Avaz Hafizli was arrested while filming in the centre of Baku and taken to a police station before eventually being released.

- On 7 January, political activist Giyas Ibrahimov attempted to set himself on fire in front of the Presidential Administration building after he failed to receive financial compensation from the Azerbaijani government in line with a ruling by the European Court. Journalists preparing a report from the scene were subjected to physical intimidation by the police and security guards. Microskop Media employee Alekper Azaev’s camera was confiscated, and his footage was deleted. He was taken to a police station before being released three hours later. The camera and phone of independent journalist Amina Mamedova were confiscated. The footage she had recorded was also deleted.

- On 15 February, police detained three journalists near the Presidential Administration building: Fatima Movlanly (Radio Azadliq), Sevinj Sadigova (Azel.tv) and freelance journalist Teymur Kerimov, who was covering a protest staged by the relatives of soldiers killed in Nagorno-Karabakh.

- On 1 March, journalists Gulnaz Gambarli, Tabriz Mirzayev and Dilara Gazanfargyzy were detained by police while trying to report from a rally outside the Russian Embassy in Azerbaijan. Security refused to allow the human rights organisation Defence Line stage a protest near the Russian Embassy in response to Russia’s human rights violations in Ukraine.

- On 27 April, blogger Nurlan Libre faced ill-treatment from police officers while filming at a metro station, where he witnessed police officers assaulting two young girls. The journalist was arrested, his phone was taken away, and he was forced to delete the footage. He was kept at the police station for about an hour.

- On 19 May, the parents of soldiers who had died in unclear circumstances tried to hold a protest in front of the Presidential Administration building, demanding that their children be recognised as martyrs. Police and security personnel arrested Radio Azadliq journalist Fatima Movlamli and Azel.TV journalist Sevinj Sadigova. They demanded that the journalists delete any photographs taken at the protest. They were eventually released.

- On 30 September, on the eve of a Popular Front Party (PFPA) protest, police began making arrests. Among those detained was freelance journalist Anar Abdullah, who was later released.

- On 23 December, dozens of protesters gathered to protest in the centre of Baku against the arrest of activist Bakhtiyar Hajiyev. They demanded that Hajiyev be released. Many journalists ran live broadcasts from the unauthorised protest. Police detained Turkyan Bashir, a reporter for the Azerbaijani service of Voice of America. The journalist said she was detained despite having journalistic accreditation.

Other incidents involving the arrests of media workers include:

- On 30 March, activist and founder of the Meclis.info platform, Imran Aliyev, was released after 20 hours in police custody. Aliyev was arrested by Ministry of Internal Affairs department employees for combating organised crime. The journalist’s family reported his disappearance: “At 2 p.m., he left the house to meet up with some friends. After this, we couldn’t contact him. More than 8 hours have passed, and there is still no information about Imran.”

- At 12 p.m. on 11 November, Mustafa Hajibeyli, the press secretary of the Musavat party and editor-in-chief of the Basta portal was detained by police near his home and taken to the Binagadi district police station in Baku. “Two men in civilian clothing were waiting for me at the entrance of an apartment building,” Hajibeyli said. “They said that the chief of police wanted to talk to me, and that I should go with them.” Hajibeyli was taken to the office of Chief Javid Ismailzadeh, after which he was taken back to his house. According to Hajibeyli, the head of the press service of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Elshad Hajiyev, called him later that day and said that he was detained “by mistake”.

Administrative prosecution, fines and arrests were common methods of exerting pressure on journalists in 2022, as was the case in previous years.

- On 12 January, the Sabunchu District Court fined Ibishbeyli Fikret (Fikret Faramazoglu), the head of Jamaz.info, 500 manats (about 300 USD) under Article 388-1.1.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“Posting information online, prohibited by the law ‘On Information, Informatisation and Protection’”) [Editors’ note: ‘informatisation’ refers to the country’s copyright regulations]. During the investigation, it was established that Fikret posted allegedly false information about the shelling of the city of Shusha, which came from the direction of Khankendi. Fikret wrote on his Facebook page that he does not agree with the court’s decision and intends to file an appeal.

- On 24 January, administrative proceedings were initiated against Yeniavaz.com employee Namig Aliyev for publishing and sharing “prohibited” information on Facebook. By the decision of the Binagadi District Court, he was imprisoned for one month under Article 388-1.1.1 (“Posting information online, prohibited by the law ‘On Information, Informatisation and Protection’”). The Prosecutor General’s Office did not, however, disclose on what material the court based his prosecution.

- On 1 February, the court sentenced blogger and Kompromat TV employee Jalil Zabidov to 25 days in prison. Zabidov was arrested in a cafe in the Yardimli district near where he lives. A few hours after he was arrested, the court found him guilty under Article 535.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“disobeying the police”).

- On 3 February, the owner of the Yeniavaz.az website, Azərmedia LLC, was fined 1,500 manats (about 900 USD) for publishing the article with criticizing comments. The Nasimi Court in Baku ruled on the case, basing its decision on an administrative protocol raised by the Prosecutor General’s Office. Head of Azərmedia, Anar Garakhanchalla, said he was summoned to the Prosecutor General’s Office on 20 January and forced to remove a link to a publication entitled “Prosecutor’s Office: Tofig Yagublu got himself into this state by beating himself up” from the Yeniavaz.az Facebook page. According to Garakhanchalla, the problem for the Prosecutor General’s Office was not the content of the article, but its title and the comments posted about the article.

- On 10 May, Eyvaz Yahyaoglu, a blogger and member of the Azerbaijan Nationalist Democratic Party (ANDP), was arrested and imprisoned for 28 days on administrative charges (“disobeying the police”). He was detained on 9 May, said Galandar Mukhtarli, chairman of the ANDP. “Eyvaz Yahyaoglu was taken from his home in Shirvan to the local police station,” Mukhtarli said. “The next day, the Shirvan City Court sentenced him to 28 days in prison, finding him guilty of disobeying the legal demands of the police (Article 535.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences of Azerbaijan). This is obviously a false accusation. They obeyed the police from the very start. What kind of insubordination are we talking about here?”

- On 27 July, the Nizami District Court in Baku sentenced journalist Tofig Shakhmuradov to a month in prison under Article 388-1.1.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“Posting information online, prohibited by the law ‘On Information, Informatisation and Protection’”).

- On 18 December, the news sites Olke.az and Manevr.az were fined 1,500 manats (about 900 USD) for violating Article 388-1.1.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“Abuse of freedom of mass information and journalistic rights”).

- On 18 December, freelance journalist Sakhavat Mamed was brought to the Prosecutor General’s Office in connection with articles he had written about the military. He was taken to the Khatai District Court, where he was fined 500 manats (about 300 USD) under Article 388-1.1. 1 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“Posting information online, prohibited by the law ‘On Information, Informatisation and Protection’”).

In 2022, several journalists were summoned to the Prosecutor General’s Office for interviews, after which they were officially cautioned:

- On 27 July, the head of the Jamaz.info website, Fikret Ibishbeyli, and the head of the Miq.az website, Agil Alyshov, were brought to the Prosecutor General’s Office. They were warned about spreading false information aimed at damaging the reputation of the Azerbaijani army.

- On 30 July, journalist Sakhavat Mamed was brought to the Prosecutor General’s Office. He was also warned about spreading false information aimed at damaging the reputation of the Azerbaijani army.

- On 15 September, the head of the YouTube channel Kanal13.TV, Aziz Orujov, was summoned to the Prosecutor General’s Office, where he was issued a warning for violating the law “On Information, Informatisation and Protection”. This followed the publication of video footage on 13 September 2022, allegedly damaging the reputation of the Azerbaijani army, and “creating doubts” about the country’s defence capabilities. “After the warning was issued, the specified materials were removed from the channel”, the prosecutor’s office noted. Orujov confirmed to the Turan agency that the call with the Prosecutor General’s Office took place and said that the published materials “were in the public interest”.

- On 19 September, Ovqat.com editor-in-chief Heydar Oguz was summoned to the Prosecutor General’s Office. Oguz wrote a series of articles about the conflict on the Azerbaijan-Armenia border. An official warning was issued, demanding that he not disclose any unconfirmed information.

- On 1 December, blogger Elmar Aziz was summoned to the Pirallahi district police department in Baku after he posted a video about traffic police officers. On 30 November, in the village of Gala, he filmed traffic police officers taking bribes from drivers and shared it on Facebook. The Pirallahi and Baku Police Departments forced him to delete the video and demanded that he not mention it to anyone. They also threatened to arrest him.

By the end of 2022, at least eight media workers were serving prison sentences:

- The founder and editor of Xeberman.com and Press-az.com, Polad Aslanov, who was arrested in 2019 on suspicion of treason, was sentenced to 16 years in prison. The Supreme Court eventually reduced his sentence from 16 to 13 years.

- The head of the Yüksəliş naminə newspaper and the news website Yukselish.info, Elchin Mammad, has been in prison since March 2020. He was sentenced to four years in prison for the theft and illegal possession of weapons.

- Blogger Aslan Gurbanov, who was arrested by the State Security Service, was sentenced to seven years in prison in 2021 for “inciting national hatred”.

- On 18 January 2022, the Nasimi District Court sentenced the founder of the Azadinfo.az website, Mahir Alekperov, to 3 and a half years in prison. During the trial, Alekperov was found guilty under Article 182.1 of the Criminal Code (“extortion”). Alekperov was accused of distributing private videos featuring Ramiz Goyushov, the leader of the Binagadi district organisation of the ruling New Azerbaijan Party. Before distributing the video, Alekperov extorted 2,000 manats (about 1,200 USD) from Goyushov. On 8 September 2022, Alekperov was arrested. Ramiz Goyushov was subsequently expelled from the party for “compromising” the government.

- On 5 July 2022, the editor of the website Demokratik.az, Osman Narimanoglu (Rzayev) was arrested on charges of extorting money from officials at the Land Reclamation Department, as well as doctors from the Goranboy and Goygol regions (Article 182.2.2 of the Criminal Code: “extortion under threat”).

- On 14 July 2022, the Yasamal District Court in Baku sentenced Abid Gafarov to one year in prison, having found him guilty of libel. The lawsuit was filed by a group of veterans of the Second Karabakh War. The judge found Gafarov guilty under Articles 147.1 (“slander”) and 148 of the Criminal Code (“insults”) and imposed a sentence of six months in prison for each. The judge did not allow Gafarov or his lawyers to make their closing statements before the court.

- On 11 September 2022, the Binagadi District Court of Baku, following an investigation by the Prosecutor General’s Office of Azerbaijan, sentenced the founder of the Khural TV website, Avaz Zeynalli, to 4 months in prison as a preventative measure. Zeynalli was prosecuted under Article 311.3.3 of the Criminal Code (“receiving large-scale bribes”), while Elchin Sadigov was tried under Article 32.5/311 (“assisting in bribery”). On 29 December 2022, the Binagadi District Court in Baku extended Zeynalli’s sentence by a further three months. As of November 2023, the trial is still ongoing.

- On 14 September 2022, the Prosecutor General’s Office announced that the head of the Səda TV internet channel, Elnur Shukyurov, had been arrested. During the investigation against Zeynalli and Sadigov, Elnur Shukurov’s illegal actions were revealed. It was established that Shukurov took 50,000 manats (about 30,000 USD) to help Salman Nasrullaev obtain the necessary certificate for the privatisation of 0.57 hectares of land and a building of 168 square metres in the Surakhani region. On 14 September, Shukurov was prosecuted under Article 312-1.1 (“illegally influencing the decision of an official”) and arrested at the request of the Binagadi court.

Other recorded incidents include:

- On 4 March, the Khachmaz District Court sentenced freelance journalist Jamil Mammadli to one and a half years of community service. The ruling, by Judge Anar Sadigov, was based on a complaint by the head of the Guba District Executive Power, Ziyaddin Aliyev. During this period, 20% of Mammadli’s monthly income will be withheld and redistributed by the state. It is worth noting that Aliyev accused Mammadli under Article 147.2 of the Criminal Code (“slander related to a serious crime”). The lawsuit was based on videos on Mammadli’s YouTube channel entitled “The Modern Period of Ancient Guba” and “Beggar Scam”. In these videos, Mammadli claims that the executive branch was embezzling funds from persons receiving welfare payments. Mammadli works as a freelance reporter. In the past, he worked as a regional correspondent for Radio Azadliq.

- On 16 March, the investigative department of the Prosecutor General’s Office imposed an emigration ban on Saadat Jahangir, an employee of Azadliq newspaper. As a result, she is unable to receive medical treatment. Jahangir told the Turan news agency that two years previously, she was brought in as a witness in a criminal case against Niyameddin Akhmedov, the bodyguard of the leader of the Popular Front Party, Ali Karimli. A search was carried out at her home, during which money, computers, and a phone were confiscated. Jahangir claims that in Azerbaijan, travel bans are used as “moral torture” against citizens with anti-establishment views.

- On 4 April, the President of the Association of Sports Journalists, Eldar Ismayilov, filed a legal complaint against the heads of three news sites: Pravda.az, Azsiyaset.com and Baku.ws (Ilkin Pireli, Samir Mamedov and Orkhan Mamedov). Ismailov, who took issue with the articles published on these sites, demanded that the three journalists be prosecuted under Articles 147.2 and 148 of the Criminal Code.

- On 14 April, the founder and editor-in-chief of the regional news site Cenub.az, Zahir Amanov, was arrested at their editorial office in the Masalli district. Law enforcement agencies reported that Amanov was detained following a complaint from the head of the Sygdash administration, Israfil Aliyev. Amanov allegedly blackmailed him by threatening to publish compromising material and was caught taking a 1,500-manat bribe (about 900 USD). A case was initiated under Article 182.1 (“extortion under threat”) of the Criminal Code.

- On 20 April, the editor-in-chief of the Xural newspaper and its associated online outlets, Avaz Zeynalli, was sued. National Assembly deputy Etibar Aliyev, who stated that his honour and dignity had been damaged by the journalist, demanded that the Binagadi District Court impose a fine of 11,000 manats (about 6,500 USD) on Zeynalli. The deputy also asked that the online Xural TV channel be shut down.

- On 12 July, the prominent Azerbaijani lawyer and politician Gurban Mammadov, who lives in the UK, sued five well-known media outlets: ARB TV, REAL TV, qafqazinfo.az, ATV and the Turan news agency. In 2020, ATV broadcast a story about Mamedov’s connections with government officials and the acquisition of property through these connections. Other media outlets subsequently shared this information. Mamedov claims this information damaged his honour, dignity and business reputation and demands a refutation and apology from these media outlets.

- On 11 November, the Azerbaijan Media Development Agency refused to include several media outlets on the state register. 24saat.org LLC, Az24saat.org, Mi-news.az and the newspaper Ogni Mingachevir were all excluded due to “unsustainable activity”. The Media Development Agency considers any media outlet that does not produce at least 20 daily articles/posts to be “unsustainable”.

ANNEX 1: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (AZERBAIJAN)

- Azadlıq Radiosu — the Azerbaijani service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- Arqument.az – an Azerbaijani news site.

- Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Center (EMDS) — a non-governmental organisation. Main goals — elections monitoring and the formation of democratic institutions in Azerbaijan.

- Freedom House – a non-profit organization based in Washington, D.C. It is best known for political advocacy surrounding issues of democracy, political freedom, and human rights.

- Gözətçi — a news site of Azerbaijan. The website aims to collate information on human rights violations.

- Meydan.TV — a weekly online television channel. Its mission — is to inform active members of society about the state of affairs in politics, the economy, and social life; to offer a platform for open and diverse discussions on all topical questions concerning Azerbaijani society.

- Reporters Without Borders – an international non-profit and non-governmental organization that safeguards the right to freedom of information.

- Turan — an independent news agency. The agency distributes news, analytical articles, and overviews from Azerbaijan.

- Toplum.TV — an Azerbaijani news site.

- Voice of America — a multimedia news organisation in the USA that produces content in over 45 of the world’s languages for audiences with limited access to a free press.