1/ KEY FINDINGS

This report covers the period from 2021 to 2023, during which almost 70% of all attacks on media workers in Russia have been recorded since monitoring began in 2017. The attacks of the Russian authorities on journalists and bloggers over the past three years have taken on an unprecedented scale. These included attacks on journalists in exile, prison sentences, torture in places of detention, pressure on relatives, loss of rights, hacking of electronic devices, exorbitant fines and mass blocking. In total, 5,262 cases of attacks/threats against professional and civilian media workers and editorial offices of traditional and online media, as well as against Russian journalists abroad, were identified and analysed in the course of this study. Data for the study were collected using content analysis from open sources in Russian and English, as well as expert interviews. A list of the main sources is provided in Annex 1.

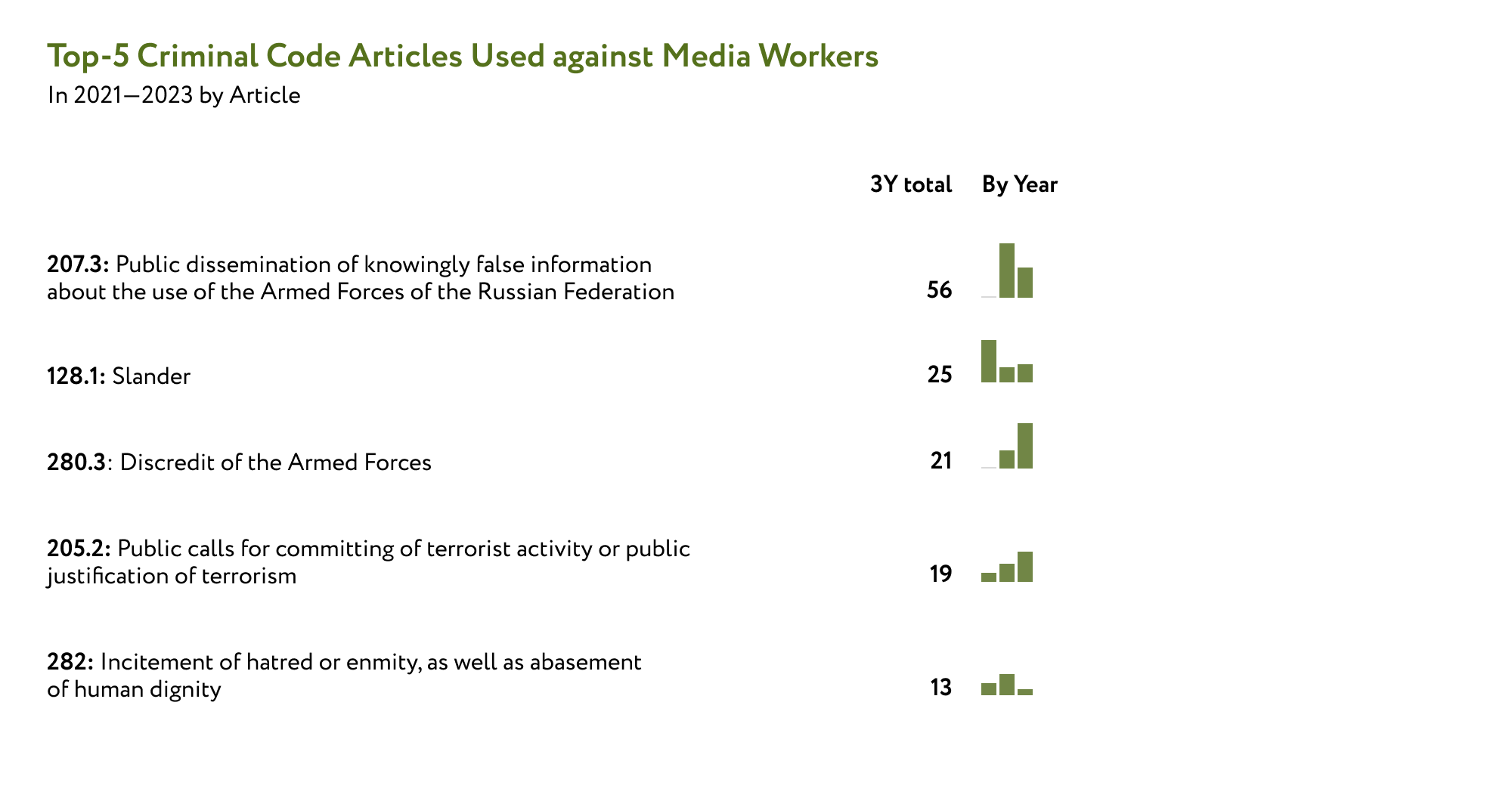

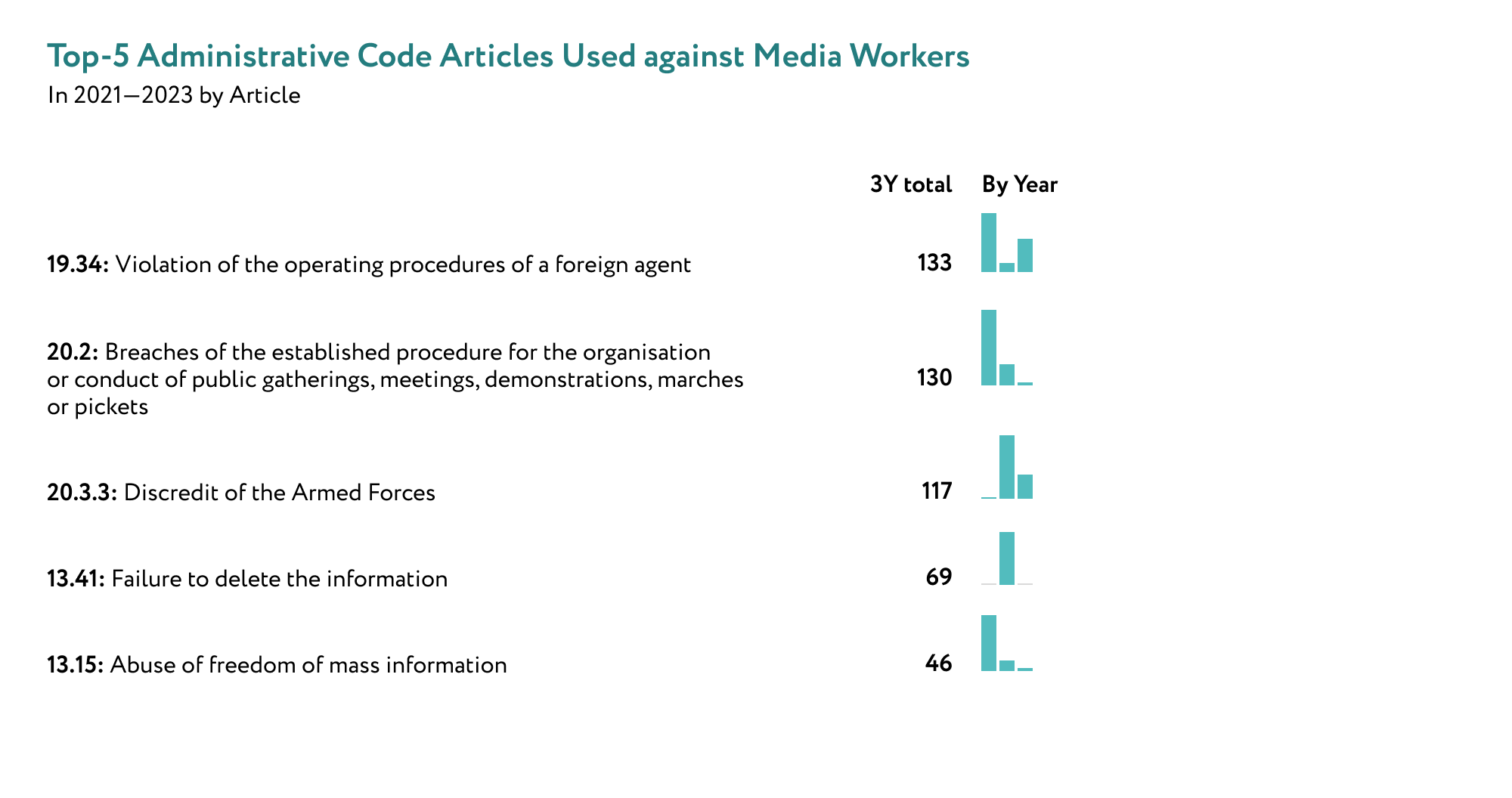

- In 2021-2023, a number of laws were adopted making it extremely difficult for journalists to do their job, freely exchange information, and provide access to independent sources for the Russian audience. The main change in this area was the laws on “military fakes” and “discrediting the army”, adopted immediately after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, prohibiting the spread of any uncensored information about the war.

- Another instrument of pressure on the independent press, stigmatisation of undesirable media and media workers, and their economic strangulation was the expanded legislation on “foreign agents” and “crimes against state security”, as well as “anti-extremist” and anti-LGBT laws. New categories of “criminal” speech have also been added to the country’s Criminal and Administrative Codes (see Annex “Repressive Legislation”)

- The slide towards “digital sovereignty” and the isolation of the RuNet has accelerated dramatically. During this period, major foreign social media sites, news aggregators, as well as hundreds of Russian, émigré and foreign media outlets, and hundreds of thousands of sites containing “undesirable” content were blocked. Journalists, bloggers, and ordinary users of social networks are being prosecuted for speaking out about the war in Ukraine, as well as the actions of the authorities, history, religion, and gender.

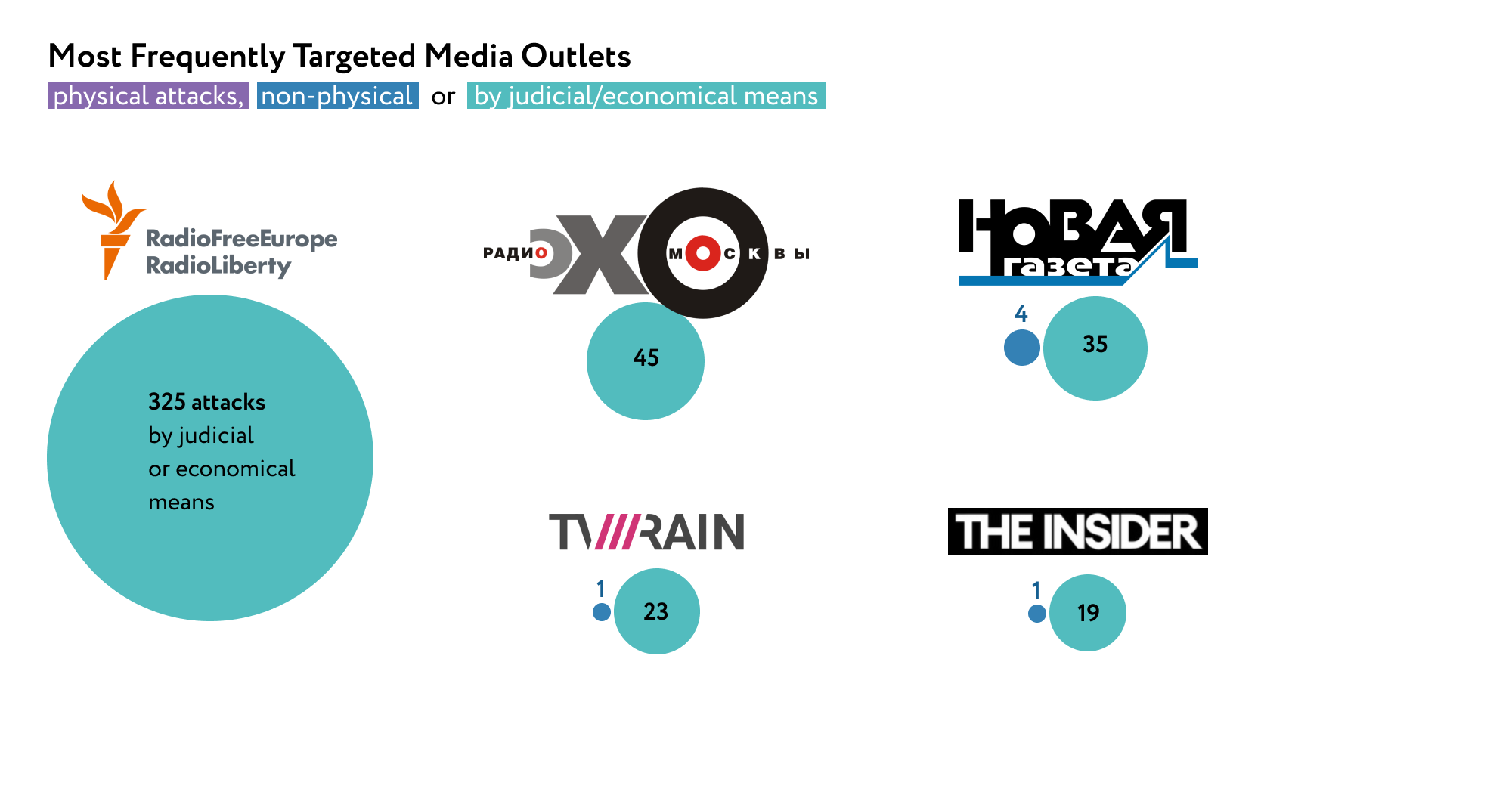

- At the end of February 2022, a crackdown on independent media began, consisting of rolling blocks, site shutdowns, and increased pressure on “undesirable” public and civil organisations. Any independent media outlets remaining in the country operate under conditions of severe censorship and self-censorship. The largest foreign NGOs, specialising in supporting independent media and civil society, have been declared “undesirable” in Russia, and those cooperating with them face prison sentences. The main independent media outlets, which are of great importance in the Russian media sphere (such as “Echo of Moscow”, “Novaya Gazeta” and the “Dozhd” TV channel), investigative journalistic projects (“Proekt”, “Insider”, “Important Stories”), as well as the media projects of Alexei Navalny’s team; have either ceased operations or continue their work from abroad. Attacks on employees of large-scale independent online news projects (7×7, Sota, RusNews) and regional outlets with a long history of persecution have become more frequent: “Pskovskaya Guberniya”, “New Focus” (Khakassia), “Fortanga” (Ingushetia), “Chernovik” (Dagestan), and “Leaflet” (Altai Republic). At least 1,500 media workers have left the country [1], while Russian émigré journalists and bloggers are also subjected to pressure and threats.

- In 2023, attacks on foreign journalists reached a new level. Foreign media and TV channels (such as Euronews, BBC News etc.) were blocked. For the first time in post-Soviet Russian history, an American journalist was sent to jail on charges of espionage. Alsu Kurmasheva, an employee of the American bureau of Radio Liberty, who is a citizen of the United States and Russia, became the first to be arrested on charges of failing to comply with the conditions associated with her status as a “foreign agent” (for more information about the cases of Evan Gershkovich and Alsu Kurmasheva, see the section “Analysis of attacks: Attacks via judicial and/or economic means”).

- The criminalisation of media consumption became the most impactful new trend emerging during this period. Control over the information sphere is now exercised not only through direct attacks against journalists, but also by threats towards users (readers, viewers, subscribers, and donors). Various penalties were introduced for the dissemination of prohibited information (almost all content of independent media falls into this category) and contacts with “undesirable” organisations. Monetary donations, as well as reposted content, hyperlinks, and screenshots became part of this. This undermines the economic models of independent media and reduces their Russian audience.

2/ METHODOLOGY

TYPES AND SOURCES OF ATTACKS

Attacks fall into three main categories: physical, non-physical (including cyber-attacks) and attacks via judicial and/or economic means. Attacks perpetrated by the state against media workers and bloggers using judicial mechanisms are often also associated with some type of physical violence, or the threat thereof (harsh detentions, violence committed during searches and assaults during detention). The Justice for Journalists Foundation, in its monitoring, doesn’t view instances of stricter penalties and changes in incarceration conditions as individual attacks.

In 2020, a new category of attacks, termed “hybrid attacks,” was introduced to better capture the collective assaults on media workers. Hybrid attacks refer to the systematic harassment of media outlets or individuals using tactics from two or more categories of attacks: physical, non-physical, and attacks via judicial and/or economic means. This blend of forceful and/or non-forceful methods, coupled with legal measures targeting “undesirable” journalists, aims to undermine their morale, coerce self-censorship, encourage departure from the profession, and has even resulted in fatalities.

In recent years, there has been a notable surge in hybrid attacks targeting “undesirable” journalists, including those who have relocated from Russia, as well as their families. These attacks utilise a wide array of influence tactics to undermine their credibility and safety.

The source of these attacks (representatives of the authorities/non-representatives of the authorities) is indicated with a certain degree of approximation in cases such as, for example, lawsuits against journalists filed by businessmen close to the authorities.

METHODOLOGICAL LIMITATIONS

- Numerous instances of pressure on media personnel, including foreign journalists working in Russia, remain undisclosed due to the risk of further repression and coercion.

- The number of administrative penalties for statements on the Internet and social media platforms is so high that no human rights organisations have complete statistics on this matter.

- Cases of content removal under threat of blocking, as a rule, are not recorded at all (it is known that social media and mass media satisfy a significant part of the relevant requirements of the Russian authorities). Numerous requests from Roskomnadzor (The Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media) to foreign hosting providers are often not recorded either.

- This report does not include facts related to the work of journalists in the conditions of hostilities and occupation in Ukraine. Attacks on journalists in Ukraine in 2022-2023 are the subject of a separate report prepared by the Justice for Journalists Foundation and the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine. Attacks on journalists in occupied Crimea in 2023 are also the subject of a separate report by the Justice for Journalists Foundation.

- The Justice for Journalists Foundation does not include attacks on beauty bloggers, showbusiness representatives and other creators of entertainment and educational content in its monitoring, although this category of media figures has been subjected to severe pressure in recent years, mostly as part of campaigns against so-called “LGBT propaganda” and targeting those who “insult to the feelings of believers/Christians”.

As such, the statistics of attacks on media workers are inevitably incomplete and inaccurate. Nevertheless, the monitoring carried out by the Justice for Journalists Foundation, as well as the analysis of its results, allows us to identify the main trends.

3/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN RUSSIA

In the World Press Freedom Index 2023 published by the international NGO Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Russia ranked 164 among a total of 180 countries [2]. This marks a significant decline compared to previous years. In 2021, Russia experienced a slight decrease in its ranking, moving from 149 to 150. However, by the end of 2021, they declined by another 5 points, followed by a further decrease of 9 points. Comparatively, in 2002, when RSF first compiled and published their World Rankings, Russia came 121st. Thus, under Putin’s leadership, the country has seen a significant decline of 43 places.

According to the report: “Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, virtually all independent media outlets have been banned, blocked, and/or declared ‘foreign agents’ or ‘undesirable organisations’. All the rest are subject to military censorship.”

GOVERNMENT-CONTROLLED MEDIA

The Russian media market is characterised by a high degree of monopolisation. The largest private media holding, “The National Media Group”, is owned by Yury Kovalchuk, a close associate of Vladimir Putin. Through his partner, Kovalchuk controls “Komsomolskaya Pravda” and owns stakes in Gazprom-Media and VK Group (since this report’s creation, Kovalchuk has also become a co-owner of Yandex [3]).

The process of nationalising regional media was almost complete by the time of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Previously independent broadcasters and print media outlets were controlled by regional authorities through a funding system – using grants and permits to cover the activities of government bodies, advertising agreements, or directly through owners.

In a survey conducted by the “Levada Centre” in 2022 [4], about two-thirds of respondents named television as their main, most trusted source of information. 39 per cent of respondents got their news from online outlets, 32 per cent – from social media (not including Telegram), and 18 per cent from Telegram channels. Similar results can be seen in a Public Opinion Foundation survey conducted in early 2023 [5].

A different picture of media use is presented by the sociological service of ANO Dialogue, a key structure in state propaganda: 46 per cent of respondents get their news from online media, 42 per cent from TV programs, and 33 per cent from Telegram channels [6]. Both pro-government and opposition pollsters show a decline in trust in television and an increase in the influence of alternative information sources. Analysts from the Re:Russia project claim that “the share of television and traditional online sources in the public’s intake of current news has decreased, while the share of Telegram, YouTube, and word of mouth has grown” [7].

Between 2021 and 2023, state investment in the creation and development of state-controlled social networks increased significantly. The main one is the “VKontakte” network (VK), which leads in the total number of users as well as in average monthly and daily reach figures. As of the first half of 2023, 71% of the country’s population over the age of 12 visited this social network at least once a month, and 43% at least once a day [8]. In 2021, the VK holding came under the control of the National Media Group and Gazprom Media. In addition to “VKontakte”, the holding includes the social network “Odnoklassniki”, the “Zen” project, and the former Yandex news service. Within this media structure, not only is pro-government content promoted, but it is also successfully used to produce entertainment content aimed at keeping users on controlled social media platforms for as long as possible. A key role in the system of production and promotion of “patriotic” content (including fake news about Ukraine) is played by the companies “Da-Team Production” and ANO “Dialogue” [9]. The latter also handles complaints from the public through specially created Regional Management Centres. The development of their own video hosting platform and the Unified Content Platform (UCP) is underway as alternatives to foreign platforms and services based on the “Chinese model” [10].

SOCIAL MEDIA

The share of internet penetration in Russia is 88.22% [12]. Social media is used by 73.3% of the Russian population. According to Mediascope, as of mid-2023, Russians over the age of 12 spend an average of 4 hours a day on the Internet, with about an hour spent on social media [13].

In 2023, Telegram became the leader among social media in terms of increased reach and time spent on the platform [14]. Telegram’s daily reach grew by 20% over the year, and by the end of 2023, nearly half of the Russian population over the age of 12 used it (the share of Russians who logged into Telegram at least once a month reached 68%)—making it the main news platform of the RuNet [15]. The growth of Telegram’s influence was especially evident during the so-called “Prigozhin rebellion,” an armed uprising by Wagner PMC fighters against the army command in June 2023 (after these events, Yevgeny Prigozhin’s media empire was dismantled). In 2022, an extensive network of pro-war propaganda channels (Z-publics) with a multi-million audience emerged on Telegram. Many large and small independent media projects also operate on this platform. In 2023, there was a significant increase in the Telegram traffic of independent regional projects [16]. According to Mediascope data for the first half of 2023, YouTube is one of the top three Internet resources in terms of average monthly reach of the Russian audience. In November 2023, the video hosting was used by 53.7 million Russians [17].

INDEPENDENT JOURNALISM IN EXILE

The censorship purge of Russian media in 2022 mainly affected independent digital media, leading to the closure of several outlets and the large-scale relocation of media projects abroad, where some independent journalists continue to face attacks and threats.

In emigration, a network of Russian media with a significant combined audience reach has emerged. This includes media that existed until 2022, as well as “relocated” and newly created outlets. According to the JX Fund [18], about 120 media outlets are operating in 30 countries (mostly in Georgia, Latvia, and Germany); the number of journalists who have left Russia since 24 February 2022, ranges from 1,500 to 1,800. A comprehensive study of 93 relocated media outlets estimated their combined reach to be between 6.7 and 9.6 million unique users, with 5.4 to 7.8 million of these users in Russia (the researchers underline that these are very rough estimates). Combined, their YouTube videos receive 165 million views every month.

“SOVEREIGNIZATION” OF THE RUNET (THE RUSSIAN INTERNET)

According to the Digital Freedom Index published in 2021 by the Proton VPN team, Russia, along with China and Cuba, ranks among the top three countries with the most severe limitations on access to networks, websites, and VPN services [19].

In the Freedom on the Net ranking, compiled annually by Freedom House, Russia saw a decrease of 7 points in 2022 (scoring 23/100 and 30/100 in 2020 and 2021 respectively), marking the sharpest decline in Internet freedoms. In 2023, the country lost an additional 2 points [20]. In the global ranking of Internet freedoms, Russia occupies the 66th position out of 70 countries under review, surpassing only China, Iran, Cuba, and Myanmar.

In 2022, the Freedom on the Net survey documented 637 thousand separate cases of interference with Internet freedom in Russia, marking a 40% increase compared to 2021. The majority of these incidents are linked to the censorship of information on various grounds, along with the blocking of individual pages, websites, and IP addresses [21].

In 2020, systematic preparatory work commenced for the isolation of the Russian segment of the Internet. By the start of the reporting period, the legislative framework for the “sovereignization of the RuNet” had been established, and efforts had intensified to develop the necessary technical infrastructure, including the mandatory implementation of national website security certificates. In 2021 and 2023, Russia conducted trial disconnections from the global network. According to the Top10VPN project, in 2023, Russia had become the country most impacted by deliberate shutdowns, with 113 million users affected [22].

Under the law on the “sovereign Internet,” starting from September 2020, Roskomnadzor mandated that telecom operators install a technology system known as TSPU (the Russian abbreviation for “technical means of countering threats”). This system, comprising hardware and software tools, facilitates the blocking and throttling of traffic through DPI (Deep Packet Inspection) technology. In March 2021, Roskomnadzor tested the capabilities of the TSPU by deliberately slowing down Twitter traffic for Russian users.

Following the onset of full-scale aggression against Ukraine, most major international IT companies exited the Russian market. In response, Russian authorities intensified pressure on foreign social media platforms through technical means such as blocking and limiting traffic, as well as administrative measures including content removal requests and imposing significant fines, including penalties for non-compliance with Russian legislation regarding the storage of users’ data.

Since 4 March 2022, Facebook has been blocked in Russia, purportedly in retaliation for the blocking of accounts belonging to Russian propaganda media on the platform. During the same month, Instagram was also blocked. Meta Platforms Inc., the owner of both platforms and the WhatsApp messenger was labelled as an “extremist organisation.” The Investigative Committee of Russia initiated a criminal case against several employees of the corporation under Articles 280 and 205.1 of the Criminal Code for “calls for extremism” and “support of terrorism” respectively. Later in 2022, more social media platforms and gaming sites were also blocked, including WikiArt, Depositphotos, Patreon, Jooble, and Chess.com.

Roskomnadzor is developing the technical infrastructure to block YouTube separately from other Google services. Since December 2022, independent monitoring has detected signs of YouTube being blocked in Russia [23].

As an alternative to blocking the world’s largest video hosting platform, there could be the establishment of a system for filtering and pirate-streaming YouTube content through an intermediary service controlled by Rostelecom, Russia’s largest digital services provider [24].

Since 2021, Russian legislation has mandated that owners of social networks monitor and delete prohibited content. In the summer of 2023, multimillion-dollar administrative fines were introduced for non-compliance with these requirements. Russia leads the world in the number of requests sent to Google demanding content removal. From 2013 to 2022, Russian authorities sent 215 thousand such requests [25]. According to Google’s transparency report, in the first half of 2023, the corporation received 36,780 requests from Russia to remove content, with two-thirds of them submitted under the pretext of “threats to national security” [26]. Google complies with a significant portion of these requests. The corporation’s report indicates that in 2022, every third request from Russian authorities to remove information was granted.

Fines imposed on international companies for their refusal to remove Russian-language content and/or disclose users’ data amount to tens of millions of dollars. In 2021, the cumulative fines imposed by Russian courts on foreign IT giants totalled 9.4 billion roubles. According to official data, in 2022 and 2023, the aggregate fines surpassed 21 billion roubles [27]. For instance, in December 2023, the Tagansky District Court of Moscow imposed a fine of 4.6 billion roubles on Google for repeated failure to remove prohibited information (Part 5 of Article 13.41 of the Code of Administrative Offences). This encompasses information regarding Russia’s conflict with Ukraine, content associated with the LGBT community, and material deemed “extremist” by Russian authorities.

Meta, TikTok, Twitch, Internet Archive, Wikipedia, GitHub, and other platforms have also incurred fines for their failure to remove “prohibited information.”

Another tactic in Russia’s campaign against prohibited content involves the blocking of VPN services. In 2022, Russia joined the ranks of the top ten countries with the highest number of VPN users, with 23 per cent of Russian residents installing such applications [28]. The implementation of TSPU has enabled authorities to effectively block VPN services.

According to Roskomsvoboda, a Russian non-governmental organisation supporting networks and protecting the digital rights of Internet users, state spending in the field of information technology for surveillance and monitoring purposes exceeded 5.6 billion roubles in 2020-2021 [29]. Based on the outcomes during the period under review, it can be concluded that not only blockings but also repressions against Internet users became partially automated.

As early as 2020, Roskomnadzor established a system for monitoring protest sentiments on the Internet. This system facilitates the exchange of relevant information with other state agencies [30]. The General Radio Frequency Centre (GRFC), reporting to Roskomnadzor, actively develops and employs such systems to track undesirable content, primarily those related to anti-war sentiments, anti-Putin sentiments, and LGBT issues. In 2023, the official launch of the “Oculus” and “Vepr” information systems was announced [32]. Additionally, the GRFC compiles dossiers on potential “foreign agents.”

In November 2022, the hacker group “CyberPartisans” provided journalists with a substantial volume of internal documentation from the GRFC. This release shed light on the technologies employed for state-initiated, politically motivated Internet surveillance and the extent of such activities [31]. Large independent media outlets and influential figures representing the opposition are among the primary targets of surveillance utilising these new technologies. Roskomnadzor has compiled personal dossiers for at least 17 Russian journalists. Additionally, in the summer of 2021, ahead of the elections to the State Duma, the GRFC provided reports on several media outlets and public organisations.

The state corporation Rostec has developed its own software package called “Okhotnik” (“Hunter”) for the de-anonymisation of Telegram channels, enabling subsequent criminal prosecution of their administrators [33].

TABOO TOPICS: WAR, NAVALNY, AND LGBT ISSUES

In the vast array of prohibited information, three main categories of content are most frequently blocked, leading to repression: materials related to the war against Ukraine, the Russian opposition, and LGBT issues.

WAR

In 2021, the censorship and repressive apparatus primarily targeted two topics across media: publications about the corruption within Putin’s inner circle and any criticism of the official version of World War II history. Any deviation from the official narrative is deemed as “humiliation” or slander against veterans and is equated with the “rehabilitation of Nazism.” Additionally, comparing Stalin’s and Hitler’s regimes is punishable by criminal law.

Since March 2022, journalists and ordinary Internet users have faced prosecution under Russia’s administrative and criminal codes for publishing information about Russian crimes in Ukraine and losses within the Russian army. Several individuals, including media workers and cultural figures who have left Russia, have been sentenced in absentia to prison terms under the article on “military fakes.”

ALEXEI NAVALNY

Following the arrest of Alexei Navalny in January 2021, large-scale repressions were initiated against his supporters. Multiple criminal cases have been initiated against Navalny and his associates. The Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) and Navalny’s Headquarters were deemed extremist organisations in the summer of 2021. Media outlets and publications affiliated with Navalny and his team are among the most frequently blocked sources. A distinct spike in censorship was linked to Navalny’s “Smart Voting” campaign in 2021.

The repercussions of the repressions directly or indirectly affected individuals involved in Alexei Navalny’s media projects: former technical director of Navalny LIVE, Daniel Kholodny, was sentenced to 8 years in prison in August 2023 in connection with an “extremist community” case; journalists Andrei Zayakin, Dmitry Nizovtsev, and others became defendants in criminal cases. Bloggers who shared content from the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) and/or distributed the company’s symbols were also impacted (for example, Mikhail Alferov – more details about his case can be found in the “General Analysis of Attacks” section); regional opposition journalists suspected of connections with Navalny’s structures were affected as well (for instance, in 2021, searches in connection with an “extremist community” case were conducted at the homes of journalists in Kemerovo, and in 2023 – in Perm); reporters covering protests against Navalny’s arrest also faced repercussions; and media outlets that reported on FBK’s investigations had about a hundred relevant publications deleted from various media platforms in early February 2022 at the demand of Roskomnadzor.

LGBT ISSUES

The heightened persecution of the LGBT community has resulted in an unprecedented level of attacks on creators of non-political entertainment content. Some of these attacks were instigated based on denunciations from special quasi-public entities. With the enactment of an expanded version of the law on “LGBT propaganda” in December 2022, Russian media outlets and bloggers faced the threat of significant fines, leading to the removal of numerous publications related to LGBT topics. Additionally, several media projects opted to change their names or cease operations altogether.

CLASSIFICATION OF INFORMATION

During the period under review, the trend towards classifying information has intensified. In addition to new regulations criminalising data collection, several registers have been closed to the public.

At the end of 2020, a law was passed allowing law enforcement agencies, judges, and prosecutors to conceal information about their employees even without an immediate threat to their safety. In February 2021, criminal liability was introduced for the disclosure of personal data of security forces personnel and officials. Towards the end of 2022, Vladimir Putin, through a decree, permitted entire categories of officials not to disclose income declarations “during the period of the special military operation.” Amidst the war and in the context of Western sanctions, Rosneft and other major companies are granted the authority not to disclose their financial statements and information about their management. In November 2023, a law on the “special procedure” for processing personal data of employees of the Ministry of Defence, the Federal Security Service (FSB), the Federal Protective Service (FSO), the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the Foreign Intelligence Service was adopted in the first reading. In December 2023, a draft of the criminal article for the illegal use of personal data was submitted. All these measures are primarily aimed at impeding journalistic investigations.

Systematic restrictions on access to official information persist. Under the pretext of safeguarding against cyber-attacks, numerous Russian state-owned websites have blocked access from foreign IP addresses. The “Network Freedoms” project highlights “the gradual closure of various state registers and services” [35]. For instance, in 2021, the Central Election Commission restricted public access to video surveillance at polling stations; In March 2023, the Federal Service for State Registration, Cadastre and Cartography (Rosreestr) discontinued access to the database of registered real estate transactions; The Ministry of Internal Affairs has impeded access to a database of wanted persons; The Moscow City Court has ceased publishing information about criminal cases involving treason, espionage, sabotage, and international terrorism.

PRESSURE ON FOREIGN JOURNALISTS IN RUSSIA

In 2022, the risks for foreign journalists in Russia escalated significantly. This primarily affects American and British citizens. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation revised accreditation rules, reducing the visa extension period from one year to three months and complicating the procedure. Additionally, the ministry expanded the list of “non-entry” media workers.

Many foreign media outlets in Russia closed in the spring of 2022. The remaining foreign correspondents are forced to adhere to significant restrictions both in gathering information (their movements are restricted, officials withhold comments, and other sources fear reprisals for contact with foreigners) and in reporting stories as they are obliged to partially comply with Russian military censorship demands. Since the end of February 2022, many foreign journalists working in Russia have ceased maintaining their social media accounts. The arrest of The Wall Street Journal correspondent Evan Gershkovich in the spring of 2023 on espionage charges triggered a new exodus of foreign correspondents from Russia. Various forms of pressure are being exerted on foreign media workers, such as lengthy interviews at border crossings, the publication of compromising information on Telegram channels associated with Russian special services, attacks on Russian embassy websites, and regular briefings with officials of the Russian Foreign Ministry.

NEW REPRESSIVE LAWS

In the period spanning 2021 to 2023, the Russian authorities have notably expanded their legal arsenal to target media outlets and media workers. This expansion aims to broaden bans on information, hinder its dissemination, tighten control over the Internet, and criminalise independent journalistic endeavours and any dissenting speech.

Due to the extensive nature of the material concerning this topic, the authors of this report have included this in a separate section (Annex 2: Repressive Legislation).

4/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

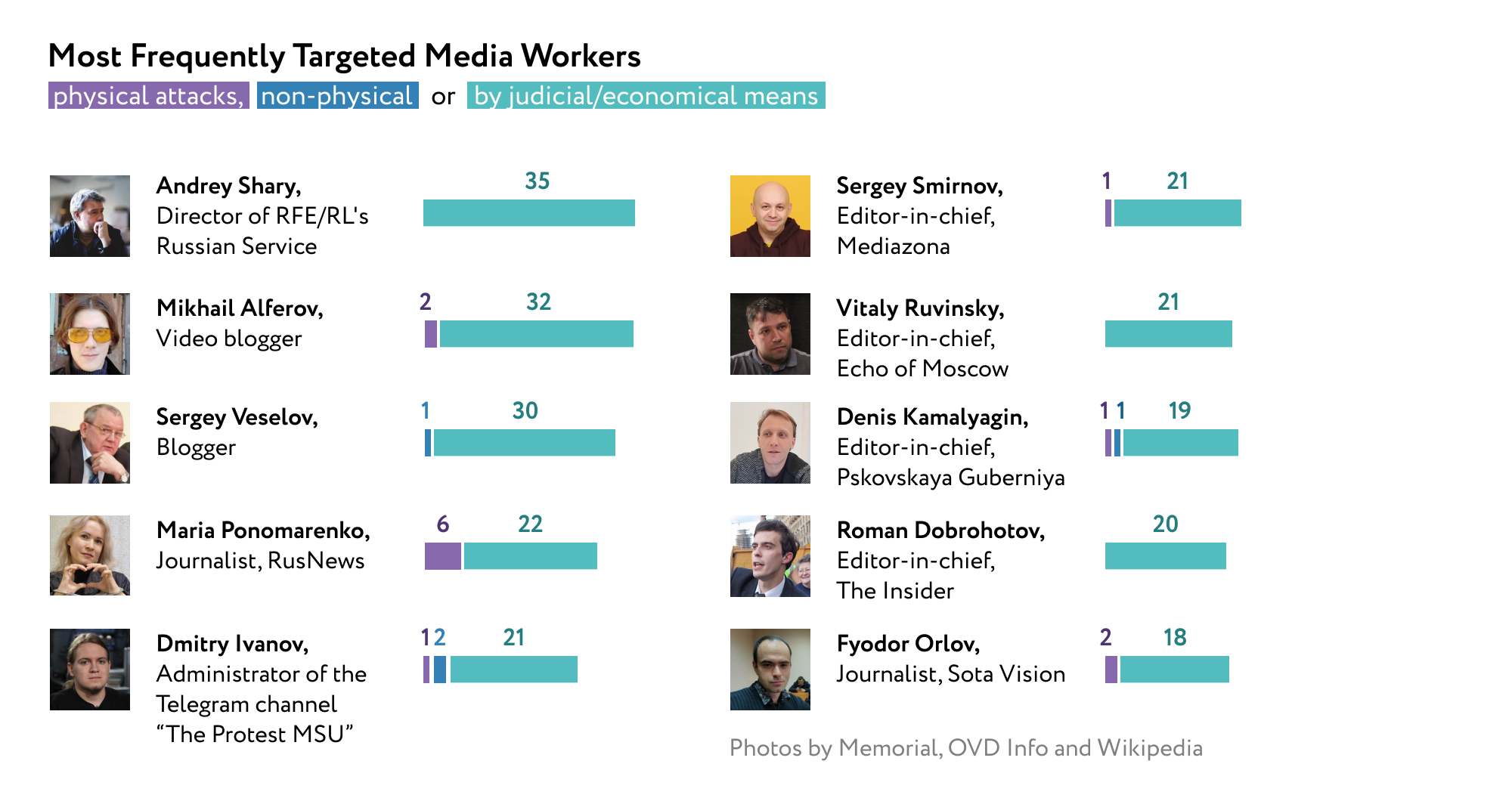

Between 2021 and 2023, the Justice for Journalists Foundation documented 5,261 cases of harassment targeting media workers and media outlets, constituting 69% of all recorded attacks since monitoring began in 2017. Among these, 205 were physical assaults, while 371 were non-physical attacks, including cyber-attacks. Pressure was exerted via judicial and/or economic means in 4,685 cases. Notably, in 92% of these cases, the attacks originated from representatives of authorities.

In 2021, compared to the previous monitoring period, there was a noticeable increase in cases of physical violence against journalists and bloggers, primarily involving harsh arrests and beatings during protest coverage. In 2022, the number of such incidents decreased by half. In 2023, the number of recorded physical attacks again dropped by more than half. This trend is associated with the “clearing” of public space, a decrease in protest activity, and the mass emigration of independent journalists and activists.

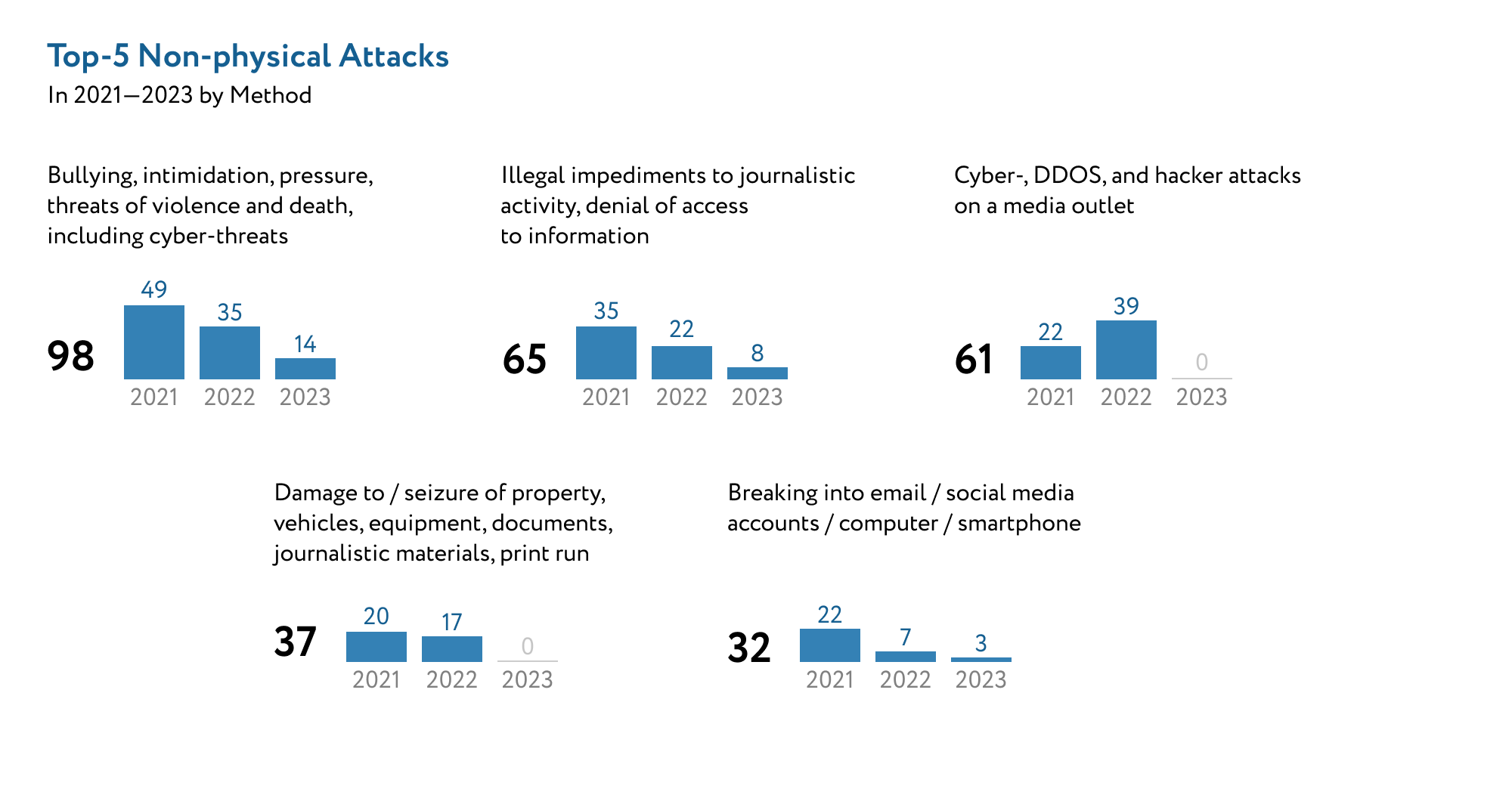

In the second major category of incidents (attacks and threats of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks), only a small part of attempts to hack accounts, threats against media workers in Russia and in exile, and cases of pressure on relatives are documented. Most of these incidents remain out of the public domain, so as repression in this category intensifies, there is also a downward trend in the number of documented incidents (190 attacks in 2021, 143 in 2022, and 38 in 2023).

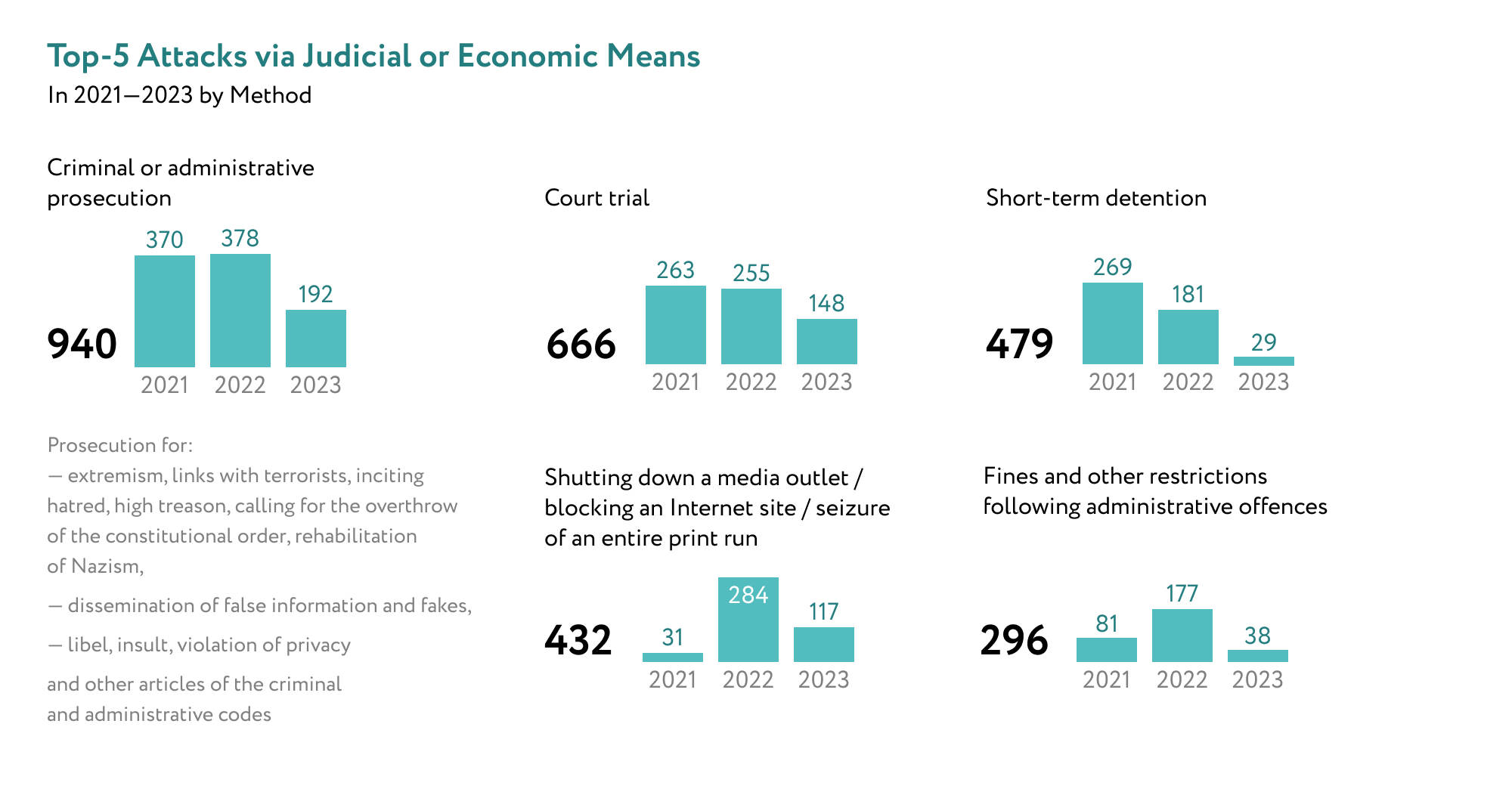

Attacks via judicial and/or economic means are the most pernicious category, as observed in previous reviewed periods. An explosive increase in repression against media workers was already observed in the Covid year of 2020 (1,059 attacks). In 2021, during the period of preparation for a full-scale war against Ukraine, the number of incidents in this category increased by more than 1.5 times (1,767 attacks). During this period, journalists were actively added to the register of “foreign agents,” and numerous administrative and criminal cases were opened against them. Finally, in 2022, a record figure of 2,034 attacks via judicial and/or economic means was reached. In 2023, after a large-scale “relocation” of uncensored media, the number of documented cases of attacks via legal means dropped dramatically, although émigré journalists continue to be prosecuted in absentia. At the same time, the proportion of sentences to real terms is growing, and the terms themselves are increasing.

5/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

Between 2021 and 2023, 205 incidents related to physical pressure were recorded, primarily non-lethal attacks. However, during this monitoring period, two murders and three attempted murders were documented:

- On 16 January 2021, the body of Zhanna Sheplyakova, the editor-in-chief of the “Ryazan.Life” portal, was discovered in an apartment in Ryazan. She had sustained numerous stab wounds. Her husband was sentenced to seven years in a high-security penal colony and ordered to pay compensation for moral damage to the victim’s brother.

- On 9 May 2022, Igor Vinnichuk, a cameraman for the “Bryansk Province” channel, was fatally wounded at the entrance of his own home after returning from work. He later died in the hospital’s intensive care unit. A 50-year-old resident of Bryansk was charged with his murder.

- In 2022, it was confirmed that Salman Tepsurkaev, the moderator of the 1ADAT Telegram channel, who was kidnapped by Chechen security forces in 2020, was killed ten days later. He endured torture and humiliation, with video recordings of the ordeal later made public.

- In August 2023, journalist Elena Kostyuchenko from “Novaya Gazeta” reported an attempted poisoning with an organochlorine compound. The incident occurred when she arrived in Germany in the autumn of 2022 after a business trip to Ukraine. Additionally, former “Echo of Moscow” journalist Irina Babloyan experienced symptoms of poisoning while in Tbilisi.

- On 6 December 2021, in Vladivostok, Tatyana Demicheva, a lawyer for the “Arsenyevskie Vesti” newspaper, was struck by a car and suffered severe injuries. Demicheva and her colleagues believe this was not an accident but an attempted murder related to her professional activities.

ASSAULT, ABDUCTION AND TORTURE

- Brothers Salekh Magamadov and Ismail Isayev, moderators of the Telegram channel “Osal Nakh 95”, have been persecuted for their anti-clerical publications and homosexuality. In 2020, they were tortured by Chechen security forces. In early 2021, 17-year-old Isaev and 20-year-old Magamadov were kidnapped in Nizhny Novgorod and taken to Chechnya, where they were again tortured and humiliated. In 2022, the brothers were sentenced to lengthy prison terms on charges of aiding terrorism.

- In December 2021, dozens of relatives of Ibragim and Abubakar Yangulbayev, outspoken Chechen activists and bloggers, and heads of the 1ADAT media project, were arbitrarily detained and intimidated in Chechnya. In January 2022, Chechen security forces kidnapped their mother, Zarema Musayeva, in Nizhny Novgorod. She was brought back to Chechnya where she became a defendant in a criminal case, and was sent to a pre-trial detention centre before being sentenced. Ramzan Kadyrov and State Duma deputy Adam Delimkhanov declared a blood feud against the Yangulbayevs and publicly threatened to kill them. Other Chechen opposition bloggers and political emigrants, Minkail Malizayev and Tumso Abdurakhmanov, also reported abductions and physical attacks against their relatives.

- On 10 June 2021, Chechen and Dagestani police broke into a shelter in Makhachkala in search of Khalimat Taramova, a victim of domestic violence who had fled Chechnya. As a result of the raid, journalist Svetlana Anokhina was violently detained. Administrative cases were opened against her and the shelter volunteers for disobeying the police.

- Tatarstan blogger and activist Karim Yamadayev, who served a prison term for his publications on charges of “propaganda of terrorism”, was subjected to violence and threats from security forces after his release. In September 2021, he was forced into a minibus, a bag was put over his head, and he was threatened with a new criminal case for filing a complaint to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). Yamadayev left Russia and applied for asylum status in France.

- On 4 July 2023, “Novaya Gazeta” journalist Yelena Milashina, who came to Chechnya to cover the trial of the mother of the above-mentioned Yangulbayev brothers, was attacked along with lawyer Alexander Nemov. They were dragged out of the car and beaten; Milashina’s head was shaved and smeared with so-called “brilliant green” antiseptic dye. In January 2022, the head of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, publicly called for reprisal against Milashina.

- On 7 April 2022, the editor-in-chief of “Novaya Gazeta”, Dmitry Muratov, was attacked in a compartment of the Moscow-Samara train. Two attackers doused him with acetone oil paint. One of them shouted: “Muratov, here’s to you for our boys.” The journalist suffered burns to his eyes. A video of the attack appeared on the “Soyuz Z paratroopers” Telegram channel, accompanied by threats towards journalists covering the war against Ukraine.

- On 9 June 2021, in Blagoveshchensk, three unknown men assaulted “Radio Liberty” journalist Andrei Afanasyev, as a result, he was partially blinded. The journalist believes that Andrei Domashenkin, a deputy of the local parliament representing the “United Russia” party, may have ordered the attack.

- On 2 May 2021, in Yakutsk, the publisher and editor-in-chief of the newspapers “Life of Yakutsk” and “Criminal Yakutia” Yuri Gorodetsky was attacked. At the entrance of his house, a poisonous liquid was splashed into the journalist’s eyes, leaving burns. Gorodetsky linked the attack to his professional activities.

- On 30 May 2022, in St. Petersburg, an attack was carried out on “Sota” journalist Pyotr Ivanov. Two attackers knocked him to the ground, beat him and photographed him. The journalist’s nose was broken.

- On 27 March 2021, the editor of the newspaper “Volya” Vlad Tupikin, was attacked in Moscow. He was punched in the face, while the attackers were shouting: “Keep on talking about neo-Nazis here!”

- On 9 September 2022, unknown individuals beat up “Caucasian Knot” correspondent Badma Byurchiyev near his house in Elista. Several people surrounded him and began to hit him on his head, and after he fell, they kept on hitting him. Presumably, the attack was related to the publication on Byurchiyev’s Telegram channel “Zangezi Chronicle”, in which he joked about the head of Kalmykia, Batu Khasikov. Subsequently, Byurchiev left Russia and applied for asylum status in Norway.

- In September 2021, while covering voting at the Russian regional elections, blogger Igor Grishin and accredited journalist Roman Ivanov were attacked in Korolev City in the Moscow region. Shortly after, searches in their homes were conducted.

- On 5 December 2022, TikToker Nikolai Lebedev (Nekoglai) posted on social media about how he was tortured and beaten at the Moscow police department. Lebedev also reported that a sexual assault attempt took place against him. One of the police officers filmed the beatings. Later, Lebedev was expelled from Russia and told he was wanted as part of a criminal case.

- Blogger Ruslan Ushakov, admin of the “Real Crime” Telegram channel, was tortured with tasers during his arrest in December 2022. In June 2023, Ushakov was sentenced to 8 years in prison on charges relating to “military fakes.”

Physical violence is often accompanied by non-physical and emotional pressure, such as bullying and humiliation. People are frequently forced to apologise for their alleged “wrongdoings” on camera, a practice that became common in 2021. Since the end of February 2022, the “OVD-Info” project has recorded at least 108 cases of forced apologies, most of them occurring in annexed Crimea [36].

TORTURE AND ABUSE IN PLACES OF DETENTION

Harsh conditions of detention and denial of medical care are prominent forms of physical attacks, torture, and abuse of journalists in custody. Here are some examples of such incidents:

- On 18 January 2023, Dmitry Ivanov, the author of the “Protest MSU” (MSU – Moscow State University) Telegram channel, was beaten by a police guard in the basement of the Timiryazevsky District Court after another court hearing. The guard struck Ivanov multiple times with a baton on the head and ribs, overly tightened his handcuffs and threatened to rape him.

- Alexander Dorogov and Yan Katelevsky, Moscow region journalists of the “Rosderzhava” project, were repeatedly subjected to physical violence after their arrest on charges of extortion. On 1 September 2021, employees of the Serpukhov pre-trial detention centre №3 were provoking and insulting Dorogov. One of them grabbed the journalist by the throat. After this, Dorogov was sent to a punishment cell, where he had to sleep on a tiled floor. In the summer of 2023, Dorogov stated that he and Katelevsky were beaten by guards in the Lyubertsy City Court. Katelevsky was taken to one session by force, despite feeling unwell having been poisoned in the pre-trial detention centre. The journalists were eventually sentenced to lengthy prison terms.

- On 17 November 2021, at a hearing in the Moscow Regional Court, during which the issue of extending the period of Dorogov and Katelevsky’s detention was decided, officers of the Federal Bailiff Service (FSSP) detained and assaulted another “Rosderzhava” journalist, Kirill Borisov. He was taken to the Sklifosovsky Research Institute hospital with a craniocerebral injury.

- Blogger Stanislav Andreev from the Kuban region (who was arrested in 2021 along with his colleague Alexei Shamardin on charges of dismantling “disabled” signs) was refused medical care in a Krasnodar pre-trial detention centre. For several weeks he was unable to eat due to an exacerbation of a chronic disease. Both bloggers were sentenced to prison terms in the autumn of 2022. In March 2021, Andreev was arrested for filming a story about police misconduct.

- Sochi-based journalist Alexander Valov, convicted in 2018 for extortion, complained in the summer of 2021 about torture in the Angarsk colony. The administration took away all his belongings and placed him in a cold cell with a sewage leak. In June 2022, Valov’s conditions of detention were changed from “strict” to “general”, but a few months later he was sent to a punishment cell and once again transferred back to “strict” conditions. In February 2023, shortly before his release, Valov was assaulted.

- In August 2022, Sergei Komandirov, an opposition blogger from Smolensk,complained in an open letter from a pre-trial detention centre, that he had not been receiving medical care for a neurological disease for seven months.

There are also frequent cases of denial of medical care to journalists and bloggers under house arrest. For example, in the fall of 2021, Kemerovo blogger Mikhail Alferov, accused of inciting hatred, was denied a visit to a doctor by an investigator after an emergency hospitalisation. In February 2022, the Federal Penitentiary Service demanded a tougher measure of restraint for DOXA editor Natalia Tyshkevich, who was under house arrest, following her emergency visit to a dentist.

PUNITIVE PSYCHIATRY

The practice of using punitive psychiatry methods against undesirable journalists and bloggers has also expanded.

- In July 2023, Vyacheslav Malakhov, the author of the online public “Pre-Revolutionary Adviser,” was hospitalised for three weeks in a psychiatric clinic in the village of Ulyanovka, Leningrad Region, at the request of the police. He was kept tied to a bed for several days and given injections of unknown drugs. Later, he was subjected to administrative and then criminal prosecution for anti-war posts.

- On 13 July 2022, journalist Maria Ponomarenko, convicted in the case of “military fakes,” was transported from Barnaul to Biysk and placed there in a psychiatric clinic, where she faced violence from the staff. The journalist was injected with an unknown drug. Subsequently, she was transferred to the Altai Regional Psychiatric Hospital, where she was prohibited from receiving letters and seeing her relatives. Upon her return to the pre-trial detention centre, Ponomarenko, who suffers from claustrophobia, was confined to a punishment cell with taped windows for a week. In September 2023, she attempted to cut her veins. On 24 March 2023, Ponomarenko was admitted to a mental hospital for three days, after which she was transferred to pre-trial detention centre No. 2 in Biysk.

- In October 2022, a military court mandated compulsory inpatient psychiatric treatment for Nizhny Novgorod blogger and activist Alexei Onoshkin, accused of disseminating “fakes” about the Russian army and inciting terrorism. The basis for the criminal charges stemmed from a post on the VKontakte social media platform regarding the destruction of the drama theatre in Mariupol, along with comments made between 2020-2021 referencing the armed struggle of the Chechens for separation from Russia.

- On 20 March 2021, Bashkir activist and blogger Ramilya Saitova was transferred from a pre-trial detention centre to the Republican Psychiatric Hospital in Bazilevka near Ufa for a comprehensive examination. The case against Saitova was initiated due to several videos on her YouTube channel. By the end of 2023, she was sentenced to 5 years in prison for “public calls for activities directed against the security of the state”.

- On 27 January 2021, the mother of Malika Dzhikayeva, a blogger from North Ossetia convicted in a drug case, stated that her daughter “is continually sent to a punishment cell for 15-day periods, and she is also being injected with some kind of drugs to induce a vegetative state”.

ATTACKS DURING PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES

Journalists from independent media outlets and bloggers are systematically mistreated by police while covering various events and protests. A series of such incidents were recorded at rallies following the arrest of Alexei Navalny in January 2021. During the dispersal of these rallies, involving the use of batons and stun guns, journalists such as Alena Istomina (Novosibirsk), Georgy Markov, Vera Ryabitskaya, Arseny Vesnin (St. Petersburg), Kristina Safonova, Nikita Stupin, Elizaveta Kirpanova, Tatyana Vasilchuk, Ekaterina Grobman, and Galina Sakharevich (Moscow), as well as Fyodor Orlov (Voronezh), among others, were injured. The OVD-Info project recorded 150 detentions of journalists and 71 administrative cases related to coverage of the January 2021 protests [37].

- On 31 January 2021, journalist Ivan Kleymenov from “The Village” was detained in Moscow near the Roman Viktyuk Theatre. A police officer struck him with a baton on the head, ribs, arms, and legs, resulting in a skull cut. Subsequently, Kleymenov was subjected to torture-like conditions for many hours inside a police van. He managed to call an ambulance, but when he arrived at the Botkin hospital, he was refused admission. Kleymenov was then returned to the police station and left overnight in the pre-detention centre.

Attacks on journalists continued in the summer of 2021 during a new wave of protests:

- On 30 June 2021, in Moscow, a police officer attacked “Mediazona” journalist Nikita Sologub while he was documenting police violence by taking photos and recording videos. The policeman grabbed Sologub by the hand and demanded that the pictures be deleted, threatening to break his arm and “cut off his tattoo”.

- On 18 July 2021, in the centre of Moscow, police detained Lenta.ru journalist Anastasia Zavyalova. She was filming the detention of a man who was being led into a police van with his young daughter. The police pushed Zavyalova, hit her head, pinned her to the ground and injured her hand. She was held at the police station for 6.5 hours.

During anti-war protests in 2022, at least 130 journalists were detained, often brutally. Reporters were also attacked while filming solo anti-war rallies. For instance, in St. Petersburg on 2 April 2022, a lieutenant colonel of the Mozhaisky Military Space Academy and his cadets assaulted “Sota” journalist Victoria Arefyeva and “Zaks.ru” photojournalist Konstantin Lenkov.

- On 5 March 2022, journalist and documentary filmmaker Sergei Yerzhenkov reported that after his detention in Kasimov, Ryazan Region, where he was filming an anti-war rally, he was tortured by the police. Subsequently, Yerzhenkov was sentenced to 8 months of restricted freedom in a vandalism case.

The next wave of police violence against media workers is associated with anti-mobilisation rallies in September 2022. In Makhachkala, “Novoye Delo” correspondent Idris Yusupov, “Caucasian Knot” journalist Murad Muradov, and the editor-in-chief of RusNews Sergei Ainbinder were detained. Ainbinder’s equipment was confiscated, and violence was used against him.

In some cases, undesirable journalists were issued summonses to the military registration and enlistment office upon detention. At least two such incidents were recorded: one with a SOTAVision journalist from Moscow, Artem Krieger, and one with a RusNews journalist from Arkhangelsk, Andrey Kichev.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

Between 2021 and 2023, there were 371 recorded incidents related to attacks, threats of a non-physical nature, and/or cyber-attacks. Although this total has decreased by five times since 2021, according to expert data, it does not reflect the real picture. In 50% of cases, these attacks originated from government officials. Threats and pressure on journalists from authorities and aggressive pro-government groups gradually intensified as the country prepared for full-scale war.

Non-physical methods of pressure, such as harassment and attempts to discredit journalists, are increasingly intertwined with the use of new repressive legislation, particularly legislation concerning “foreign agents.”

- In July 2021, “Dozhd” TV journalist Anna Mongait received threats that appeared to originate from the right-wing radical movement “Male State” after her interview with a same-sex couple. The individuals behind the messages insulted Mongait, demanded a public apology, and threatened to “slaughter her children.”

Journalists receive threats even after they leave the country. In many cases, the pressure is applied to their relatives.

- On 24 July 2023, The Insider journalist Marfa Smirnova, who lives in Georgia, reported instances of pressure and surveillance targeting her relatives who remained in Russia. According to Smirnova, since April 2023, she has been receiving anonymous threats, which include photos of her relatives, their travel routes, and other private information. Notably, she received an audio recording of a wiretap from her Moscow apartment.

Other examples include the lawsuit between former Channel One editor and now political refugee Marina Ovsyannikova and her ex-husband over child custody, searches at the homes of the parents of “Sota” journalist Anna Loiko (November 2023) and “Mediazona” publisher Pyotr Verzilov (December 2022), and pressure on the parents and father-in-law of persecuted Ingush journalist Izabella Yevloeva (June 2022).

Not only has harassment and pressure intensified, but cyber-attacks have also reached a new level following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the mass exodus of media workers from Russia. The technical capabilities and sophistication of those targeting journalists have significantly increased.

The hacking and attempted hacking of journalists’ personal accounts on social networks and messaging platforms has become almost routine. Journalists such as Denis Kamalyagin, Anton Dolin, Maxim Blunt, Vasily Krestyaninov, Nikita Mogutin, Ilya Rozhdestvensky, Viktor Ovsyukov, Maxim Glikin, Fyodor Orlov, and many others have been targeted by such attacks. Phishing and spam attacks are also widely used.

The most high-profile case that received international attention was the attack involving the use of the Pegasus spyware.

- In September 2023, it was revealed that the Pegasus spyware had been installed on the smartphone of Meduza publisher Galina Timchenko. This program grants full access to the contents of the “infected” phone. Timchenko’s iPhone was hacked in February 2023, just two weeks after Meduza was declared an “undesirable organisation” in Russia. Recently, Timchenko participated in a closed-door meeting of representatives from Russian independent media in Berlin, where the legal aspects of working under censorship and persecution of journalists were discussed. The source of the attack has not been identified. The manufacturer of the Pegasus program, the Israeli company NSO, sells it only to legitimate authorities, and it is used by intelligence services in several countries.

- During the same period, three Russian journalists working in the Baltic countries received notifications from Apple warning of a possible hack. They are Yevgeny Erlikh from the “Current Time” TV channel, Maria Epifanova, general director of “Novaya Gazeta Europe,” and Yevgeny Pavlov, correspondent of “Novaya Gazeta Baltia.”

- In April 2022, several journalists from the “Pskovskaya Guberniya” media and many of their colleagues from other independent media outlets experienced a massive spam attack on their mobile phones. They began to receive numerous calls and SMS messages with codes confirming registration in various services, including “Gosuslugi” (Federal State Information System “Unified Portal of State and Municipal Services), banks, and stores. Such attacks were reported by journalists from “Dozhd,” “Echo of Moscow,” “Bumaga,” “Mediazona,” “7×7,” “The Village,” and “Republic.”

- In December 2022, “The Insider” journalist Vasily Krestyaninov, based in Armenia, reported that his account on “Gosuslugi” had been hacked. He found that he had been signed up as a volunteer to fight in the war against Ukraine.

- In December 2022, Buryat journalist Evgenia Baltatarova reported that her account had been hacked and her Telegram channel stolen. Subsequently, Baltatarova was prosecuted under the article on “military fakes.”

- In August 2021, unknown individuals launched a spam attack on the mobile phones of “Important Stories” journalists Iryna Dolinina and Alesya Marokhovskaya.

A particularly alarming case involves harassment and illegal surveillance of journalists in exile. On 19 September 2023, Iryna Dolinina, a journalist for “Important Stories,” and her colleague Alesya Marokhovskaya, reported receiving anonymous threats through a feedback form on the outlet’s website. The unidentified individuals made it clear that they knew not only the addresses of both journalists in Prague but also other personal information, including their travel plans.

According to the “Network Freedoms” Project, there has been a gradual increase in the number of attempts to hack journalists’ personal accounts and attacks on media websites since 2017. In 2022, an alarming growth was recorded, with 371 cyber-attacks on activists, journalists, and the media, surpassing the total figures for the previous eight years combined. These attacks mainly consisted of DDoS attacks on the websites of regional outlets, with StormWall experts registering at least 270 such incidents [38].

In the first weeks after the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian army, graffiti with the letters Z and V (symbols of the “special operation”), as well as insults and threats began appearing on the front doors of some independent media workers in Moscow:

- On 6 March 2022, film critic Anton Dolin spoke about his forced departure from Russia, citing the country’s aggression against Ukraine and the introduction of military censorship as reasons. Dolin’s messenger accounts were hacked. In the early days of the full-scale invasion, unknown individuals painted the letter Z in white paint on the door of his apartment. Later, Dolin announced his resignation from the position of editor-in-chief of the magazine “Iskusstvo Kino.”

- On 11 March 2022, after the former editor-in-chief of “Theatre” magazine, Marina Davydova, having made an anti-war appeal, began to receive numerous anonymous threats via SMS and email. The letter Z was painted on the front door of her apartment. Davydova was also under surveillance: a video of her leaving the country was posted on a pro-government Telegram channel. At border control, Davydova was subjected to a lengthy cross-examination by FSB officers.

- On 17 March 2022, the letter Z and a message reading “Don’t sell out your motherland, Dima” was written on the door of Dmitry Ivanov’s apartment, the admin of the “Protest MSU” (MSU- Moscow State University) Telegram channel.

- On 17 March 2022, an inscription inwhite paint saying”Let’s end this war” appearedon the apartment door of “Sota Vision” journalist Anna Loiko. In Russian this message starts with the capital letter Z, which is one of the symbols of Russian aggression against Ukraine.

- On 24 March 2022, an unknown person in the uniform of a delivery service courier planted a pig’s head wearing a wig by the front door of the editor-in-chief of “Echo of Moscow”, Alexei Venediktov. On the door, he found the Ukrainian coat of arms and the word “Judensau”, which is an insult towards Jewish people.

- On 30 April 2022, journalist Ekaterina Milenkaya found the inscription “I found you, whore” on her door, along with a funeral wreath. Milenkaya has repeatedly received threats due to her anti-war stance. Up until 2018, she worked at the “Penza” State Television and Radio Company.

- On 26 July 2022, a poster with the message “Traitor, Be Afraid” and a funeral wreath was left outside the apartment of Kirill Sukhorukov, the founder of the project “Kaliningrad is firing Putin.” Additionally, the letters Z and V were painted on the door, and two photographs of Sukhorukov were glued to it, one of which had been crossed out with a red marker.

5/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

The repression of Russian media workers has expanded since 2020, but the record was set in 2022 when the number of recorded attacks using repressive laws reached 2,033. The explosive growth was due to the introduction of military censorship and prosecutions under new criminal and administrative articles, which were introduced immediately after the start of the full-scale invasion.

In 2021, investigative journalist teams from “Important Stories,” “Proekt,” and “The Insider” faced prosecution. During the spring and summer, security forces conducted hours-long searches at the homes of Roman Anin, editor-in-chief of “Important Stories,” key employees of the “Proekt” outlet, as well as Roman Dobrokhotov, editor-in-chief of “The Insider.” These searches were carried out on charges of libel and violation of privacy. In 2022, searches and seizures took place in the editorial office of the “Pskovskaya Guberniya” media. In the autumn of the same year, a series of searches were conducted in connection with the case of calls for terrorism on the Internet, initiated against journalist Andrei Grigoriev. Later, all of these journalists left Russia.

Administrative arrests were also widely used. In 2021, the editor-in-chief of “Mediazona,” Sergei Smirnov, was imprisoned for 15 days for posting a humorous tweet, having been accused of calling for participation in an unsanctioned rally.

In 2022, the Justice for Journalists Foundation introduced a new subcategory of attacks – “forced cessation of journalistic activities or closure of media outlets based on martial law and/or the introduction of military censorship”. At least 14 such incidents were recorded against “Dozhd,” “Znak.com,” TV-2, Bloomberg, “Novaya Gazeta,” Ykt.Ru, Colta.ru, “Novaya Novogorodskaya Gazeta,” Sakh.com, “Barents Press International,” “ProVladimir,” “Tagilka” newspaper, “Real Tagil” TV channel, and the Telegram channel “Avtozak LIVE.”

In 2022, the “Network Freedoms” Project recorded 779 cases of criminal prosecution for expressing opinions on the Internet, marking the highest annual figure in 15 years. The OVD-Info project, which conducts the most comprehensive monitoring of political repression in Russia, provides the total number of prosecution cases for speaking out from 2021 to 2023: 848 people, with 322 of them imprisoned. Among these prosecutions for anti-war speeches and statements, the leading cases involve “military fakes” (297 defendants), “discrediting” the army (140), and “justification, propaganda, or calls for terrorism” (122) [39].

According to OVD-Info, 58 journalists in Russia were involved in criminal cases in 2022, and the number rose to 113 in 2023. The authors of the final report on Russian repression noted, “In 2022, the most common type of pressure on media workers was blocking, while in 2023, it shifted to criminal cases” [40].

TREASON, ESPIONAGE, COOPERATION WITH A FOREIGN STATE

According to calculations by “Mediazona” in 2023, at least 101 people in Russia became defendants in criminal cases under articles on treason (Article 275 of the Criminal Code), espionage (Article 276 of the Criminal Code), and cooperation with foreign states or organisations (Article 275.1 of the Criminal Code) [41]. Journalists were prosecuted under all three articles.

- In September 2022, Ivan Safronov, a former journalist for “Kommersant” and “Vedomosti” and a specialist in the defence industry, was sentenced to 22 years in a high-security penal colony and fined half a million roubles for treason.

- Evan Gershkovich, a journalist for The Wall Street Journal, was detained in Yekaterinburg at the end of March 2023 and sent to the Lefortovo pre-trial detention centre in Moscow on charges of espionage. The FSB claims that Gershkovich “on instructions from the American side, collected information constituting a state secret about the functioning of an enterprise of the Russian military-industrial complex.” This marks the first arrest of an American journalist in Russia on espionage charges since the Cold War.

- On 17 April 2023, politician and journalist Vladimir Kara-Murza was sentenced to 25 years of strict regime under articles on treason, “military fakes,” and involvement in the activities of an “undesirable” organisation. The verdict also includes a ban on practising journalism for seven years after serving the sentence. This is the first known case where the article on treason in the expanded edition was applied.

- In December 2023, Felix Yeliseev, the author of the “Kolkhoz Madness” Telegram channel and former administrator of the group “She Fell Apart,” was sentenced to 14 years in a high-security penal colony in a case of treason and justification of terrorism on the Internet (Part 2 of Article 205.2 of the Criminal Code). Yeliseev’s anti-war publications were cited as the reason for the criminal prosecution. He was charged with treason for donating money to the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

- Nika Novak, a journalist from Chita and the former editor-in-chief of the Zab.ru website, was one of the first defendants in a case under Article 275.1 (“cooperation with a foreign state/organisation”), introduced to the Criminal Code in July 2022. She was arrested in December 2023, and the details of the case remain unknown.

In total, according to the project “Pervyi Otdel” (“First Department”), courts in Russia have received seven cases for review under Article 275.1, three of which have resulted in convictions, and one – in “enforced measures of a medical nature” [42].

- In October 2021, Andrei Pyzh, a video blogger from St. Petersburg, was sentenced to 5 years under paragraph “D” of Part 2 of Article 283.1 of the Criminal Code (“illegal receipt of information constituting state secrets, associated with its distribution and relocating devices containing the information abroad”). Pyzh was prosecuted for so-called “digger” filming.

PROSECUTION FOR “MILITARY FAKES” AND “DISCREDITING THE ARMY”

New articles of the Code of Administrative Offences and the Criminal Code on military censorship, introduced in 2022, have become the primary tool for the legal prosecution of media workers. In criminal cases of “military fakes” and “repeated discrediting” of the army, the proportion of sentences resulting in actual prison terms is on the rise: from 46 per cent in 2022 to 60 per cent in 2023 [43]. In the first 9 months after the introduction of the article on “military fakes,” 180 criminal cases were opened against 146 people [44].

- On 15 February 2023, a court in Barnaul sentenced “RusNews” journalist Maria Ponomarenko to six years in prison. She was found guilty of spreading false information about the Russian army. Ponomarenko was also prohibited from participating in public online activities for 5 years.

- In March 2023, “Kuzbass” journalist Andrei Novashov was sentenced to correctional labour under the same Article for reposting Viktoria Ivleva’s text “Mariupol. Blockade”.

- In September 2023, the editor-in-chief of the Khakassian media outlet “Novy Fokus,” Mikhail Afanasyev, was sentenced to 5.5 years in prison for publishing information about Rosgvardia personnel who were dismissed for refusing to fight in Ukraine. The media outlet, which had faced numerous attacks by the authorities, was later liquidated by a court decision.

- In the same month, blogger Alexander Nozdrinov (“Sanya Novokubansk”) from the Kuban region was sentenced to 8.5 years in prison under the same Article (military fakes) for a post about the consequences of the Russian shelling of Kyiv.

- In 2022, three more cases of “military fakes” were opened against the founder of the Ingush media outlet “Fortanga,” Isabella Yevloeva, who is living in exile.

The defendants in similar cases included “RusNews” journalist Roman Ivanov (sentenced to seven years in prison on 6 March 2024) and Sergei Mikhailov, publisher of the Gorno-Altai newspaper “Listok” (who has been in custody since 13 April 2022). Verdicts in absentia under the Article on “military fakes” were issued against the following emigre journalists and bloggers: Nika Belotserkovskaya, Pyotr Verzilov, Ilya Krasilshchik, Alexander Nevzorov, Michael Naka, Ruslan Leviev, Vladimir Milov, Maxim Katz, Alexandra Garmazhapova, and Marina Ovsyannikova. Ukrainian journalists Maria Efrosinina and Dmitro Gordon were also arrested in absentia under the same Article, and American journalist Masha Gessen was put on the wanted list.

Most criminal cases for “discrediting the army” are initiated under Part 1 of Article 280.3 after the decision on the relevant administrative case has entered into force (Article 20.3.3 of the Administrative Code). In the first 10 months of the war in Ukraine alone, the courts issued fines of more than 150 million roubles under this administrative Article [45]. In 2022, according to the State Automated System “Justice,” Russian courts considered at least 3,873 such cases.

For example, the defendants in criminal cases of “repeated discrediting” (Article 280.3 of the Criminal Code) included the editor-in-chief of the newspaper “Sovremennaya Kalmykia,” Valery Badmaev (sentenced to a fine of 150 thousand roubles), Novorossiysk video blogger Askhabali Alibekov (sentenced to 14 months in prison), Dagestani journalist and activist Svetlana Anokhina, among others.

Article 20.3.4 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“calls for sanctions against Russia, its organisations and citizens”) is also applied against journalists. In 2022, the Gorno-Altai weekly edition of “Listok” was fined 300 thousand roubles under this Article. Its editor-in-chief Viktor Rau, who lives outside of Russia, was fined 120 thousand roubles.

PROSECUTION FOR “TERRORISM” AND “EXTREMISM”

In Russia, the use of “anti-terrorist” articles, in particular Article 205.2 of the Criminal Code (“public justification” or “propaganda” of terrorism), continues to expand rapidly. According to estimates from the expert and discussion platform Re:Russia, the number of people convicted under this Article in 2022 (274) increased by 27 times compared to 2014 [46]. According to “Mediazona,” for two years in a row, more than 350 criminal cases under Article 205.2 of the Criminal Code on the justification of terrorism have been submitted to the courts in Russia [47]. Along with the articles on “military fakes” and “discrediting the army,” this is an instrument of repression for public statements. According to OVD-Info, at least 134 criminal cases were opened in 2023 for “calls for extremism, terrorism, and anti-state activities.”

- In June 2021, a criminal case under Part 2 of Article 205.2 of the Criminal Code was initiated against St. Petersburg video blogger Yuri Khovansky for a song about the terrorist attack on Dubrovka (the Moscow theatre siege in 2002), performed on another blogger’s stream in 2012. The case was later dropped.

- Blogger Islam Belokiev from Ingushetia, a former press secretary of the Chechen battalion of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, was put on the federal wanted list in 2021 on charges of participation in an illegal armed group, financing terrorism, inciting terrorism, and rehabilitation of Nazism. In March 2023, a case was opened against Belokiev for spreading “military fakes,” and in December – for justification of terrorism.

- In November 2022, Andrei Grigoriev, a journalist for “Idel.Realii,” was arrested in absentia in Kazan. He was charged with justification of terrorism (Part 2 of Article 205.2 of the Criminal Code).

- In September 2023, Abdulmumin Gadzhiyev, a journalist for the Dagestani newspaper “Chernovik,” was sentenced to 17 years in prison for “organising the finances of a terrorist group” (Part 4 of Article 205.1 of the Criminal Code), “participation in a terrorist organisation” (Part 2 of Article 205.5 of the Criminal Code), and “organising the activities of an extremist organisation” (Part 2 of Article 282.2 of the Criminal Code).

In 2023, a new repressive instrument was added to the arsenal of state bodies. Article 280.4 of the Criminal Code allows persecution on grounds of calls for activities against the security of the state. Four cases of implementation of this law have already been recorded.

- On 17 August 2023, a criminal case was opened against Sergei Ukhov, the former coordinator of Navalny’s Perm headquarters and founder of “Perm 36.6”, for “public calls for activities against the security of the state.” Ukhov fled the country and was placed on the federal wanted list. That same day, the homes of four individuals in Perm were searched in connection with his case.

- In September 2023, Kazan blogger Parvinakhan Abuzarova received a three-year prison sentence in a case related to calls for desertion (Paragraph “C” of Part 2 of Article 280.4 of the Criminal Code).

- In December 2023, Bashkir political activist and blogger Ramilya Saitova was sentenced to five years in prison under the same article for a video urging those who had been mobilised to the Russian army “not to engage in combat in Ukraine”. Previously, in the autumn of 2021, Saitova had been sentenced to three years in a penal colony on charges of inciting extremism.

- On 9 December 2023, a criminal case was brought against Andrei Serafimov, a journalist from “Novaya Gazeta”, for “calling for activities against the security of the state”. The exact reason for this remains unknown. Serafimov, who suggested that the case might be linked to his social media posts, in which he advised people to avoid military conscription, is currently living outside of Russia. Additionally, law enforcement officers visited his relatives twice for questioning and summoned them for interrogation. They also visited the university where Serafimov is enrolled.

“Anti-extremist” legislation continued to be applied against so-called “undesirable” bloggers.

- On 11 February 2021, in Chita, blogger Alexei Zakruzhny, also known as Lekha Kochegar, was convicted under Part 2 of Article 280 of the Criminal Code (“public calls for extremist activity on the Internet”) and Part 3 of Article 212 of the Criminal Code for (“inciting mass riots”). He received a probationary sentence along with a three-year prohibition on running websites, and his equipment was confiscated. Zakruzhny has faced multiple other legal cases.

- In the summer of 2021, Kemerovo blogger Mikhail Alferov was placed under house arrest for “inciting hatred against a social group” (Part 1 of Article 282 of the Criminal Code) for a video about the arrest of Alexei Navalny. Later, he was also found guilty of “rehabilitation of Nazism” (Part 3, Article 354.1 of the Criminal Code) and “insulting security forces” (Article 319 of the Criminal Code). The court sentenced the blogger to a 2.5-year ban on certain actions. In addition, Alferov was sentenced to administrative arrest for “inciting hatred” (Article 20.3.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences).

PROSECUTION FOR “REHABILITATION OF NAZISM”

According to OVD-Info, in 2023, over 45 politically motivated cases were initiated for the “rehabilitation of Nazism” under Article 354.1 of the Criminal Code. OVD-Info noted that part 4 of the article (“expression of clearly disrespectful views and/or information about the days of military glory and memorable dates of Russian history by a group of people or on the Internet”) was the most commonly used by security forces.

- In 2021, journalist Sergei Reznik from Rostov faced accusations of rehabilitating Nazism for a statement about World War II on his personal Telegram channel, having been targeted previously for his journalistic work.

- In January 2022, “Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty” was fined three million roubles under an administrative article on the “rehabilitation of Nazism” (Part 4.1 of Article 13.15 of the Code of Administrative Offences) for an article by historian Boris Sokolov about a ciphergram of Marshal Georgy Zhukov.

- In April 2022, a journalist and “What? Where? When?” TV show participant Rovshan Askerov faced a case under Part 4 of Article 354.1 of the Criminal Code for a social media post about Marshal Georgy Zhukov.

- In October 2023, St. Petersburg journalist and local historian Dmitry Vitushkin was arrested on charges of rehabilitating Nazism online and desecrating symbols of Russia’s military glory on the Internet. The authorities found these offences in Vitushkin’s post about Finnish sniper Simo Häyhä, where the Soviets involved in the Winter War of 1939-1940 were referred to as occupiers.

Articles on libel (Article 128.1 of the Criminal Code) and invasion of privacy (Article 137 of the Criminal Code) are also used to attack journalists and bloggers. In addition to this, a number of civil defamation lawsuits were filed against media workers and media outlets (128 incidents).

- In August 2021, the Ostankino District Court of Moscow fully upheld dancer Aya Belova’s claim against “Important Stories”, Roman Shleynov (the editor of the investigative department at the media outlet), and the “Dozhd” TV channel. The court ruled in favour of Belova, ordering “IStories” to remove the investigation from its platform regarding Rosneft’s purchase of shares in the Italian company Pirelli, alleging Belova’s involvement in the scheme. Additionally, the court mandated the publication of a refutation.

During the period under review, cases of extortion (Article 163 of the Criminal Code) were initiated against at least 9 media workers. Among the charges brought against the founder of the “Police Ombudsman” project, Vladimir Vorontsov, was extortion, for which he was sentenced to 5 years in prison in August 2022. Starting from 2022, arrests of Telegram channel admins under Article 163 of the Criminal Code have become more frequent, with senior manager of Rostec Vasily Brovko initiating a number of such cases. The court case against the public admins of the “Scanner Project” resulted in sentences of 8 years in prison.

‘FOREIGN AGENTS’

In July 2022, a framework law on “foreign agents” was adopted. This law paved the way for designating individuals, organisations, or banks as “foreign agents” if they were deemed to be under foreign influence or received support from abroad. In December 2022, when the law came into force, additional restrictions — professional, civil, and financial — were introduced for those included in the “foreign agents” register. New regulations for labelling any content produced by “foreign agents” were also approved.

According to the “Inoteka” project [49], as of the end of December 2023, there were 254 individuals and legal entities from the media sphere listed in the registers of “foreign agents” (including media outlets and their employees with the status of “foreign agent” or “foreign agent media”). In 2021, 39 journalists (including Roman Badanin, Roman Anin, and Olesya Shmagun) and 20 media organisations were added to the register of “foreign agents”. In 2022, the number increased to 72 journalists and 20 media organisations, while in 2023, it was 59 journalists and 23 media organisations.

In addition to this, in June 2023, information about a closed register of “individuals affiliated with ‘foreign agents'” first surfaced. A document published by the Ministry of Justice revealed that by 31 December 2022, 861 people, including many journalists and bloggers, had been named in it [50].