AUTHOR OF THE REPORT- NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS OF UKRAINE

PHOTO: Volodymyr Pavlov, NUJU

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Ukraine, 89 attacks/threats against professional and civil media workers, editorial offices of traditional and online media outlets were identified and analysed in the course of the study for 2023. Data for the study were collected using content analysis from open sources in three languages: Ukrainian, Russian, and English. A list of the main sources is provided in Annex 1. To verify the cases and further classify them, data was used from a survey of more than 100 individuals conducted by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU). These included injured media workers, as well as the relatives and colleagues of injured/killed journalists.

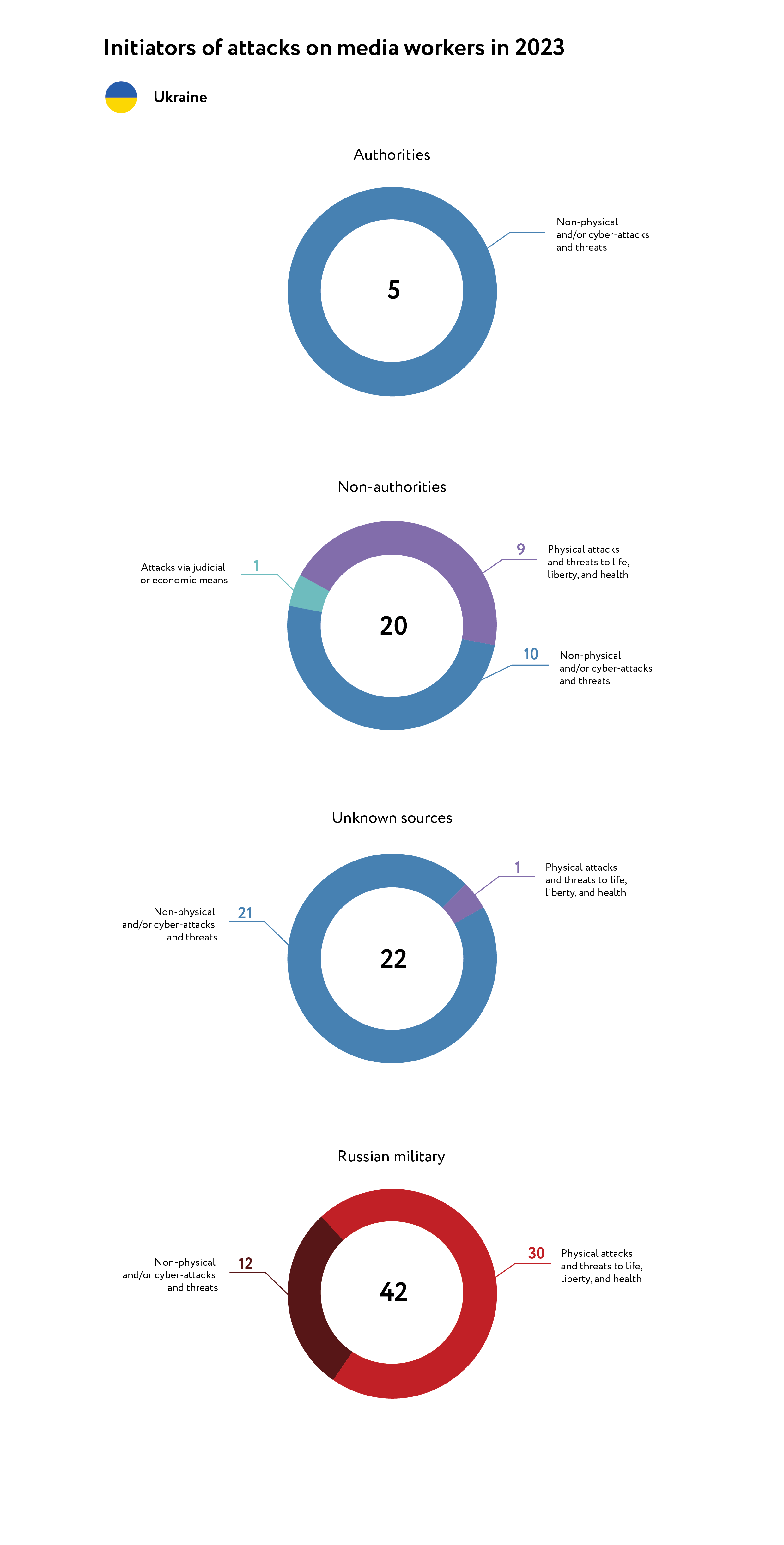

- Amid the full-scale invasion, 47% of the incidents that occurred in Ukrainian-controlled territory came from the Russian military. In 2023, there were 3 times fewer incidents recorded than in 2022.

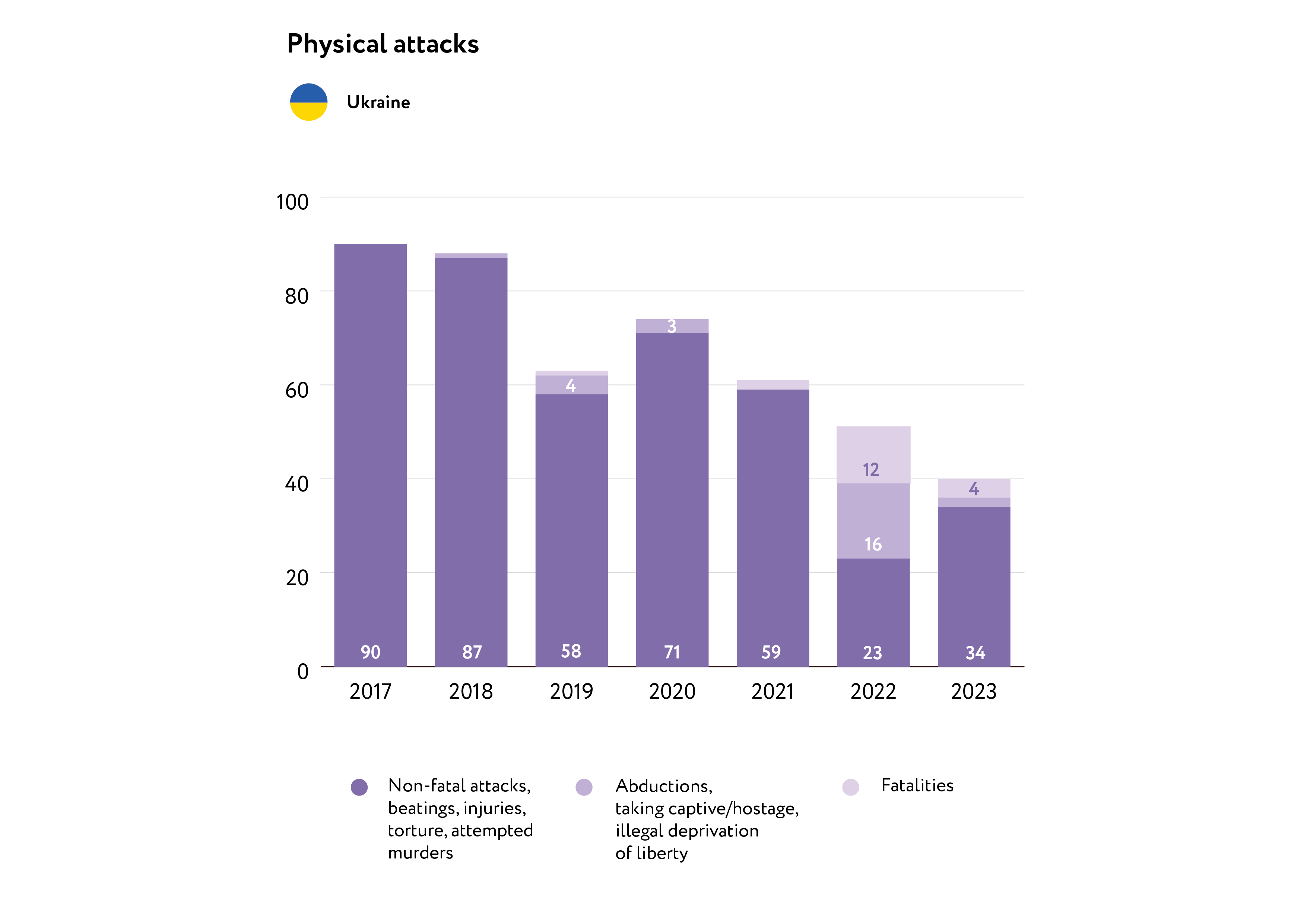

- As a result of Russian aggression in 2022-2023, 16 media workers died in Ukrainian-controlled territory while performing their professional duties.

- As in previous years, attacks and threats of a non-physical nature remain the most common methods of pressure on media workers.

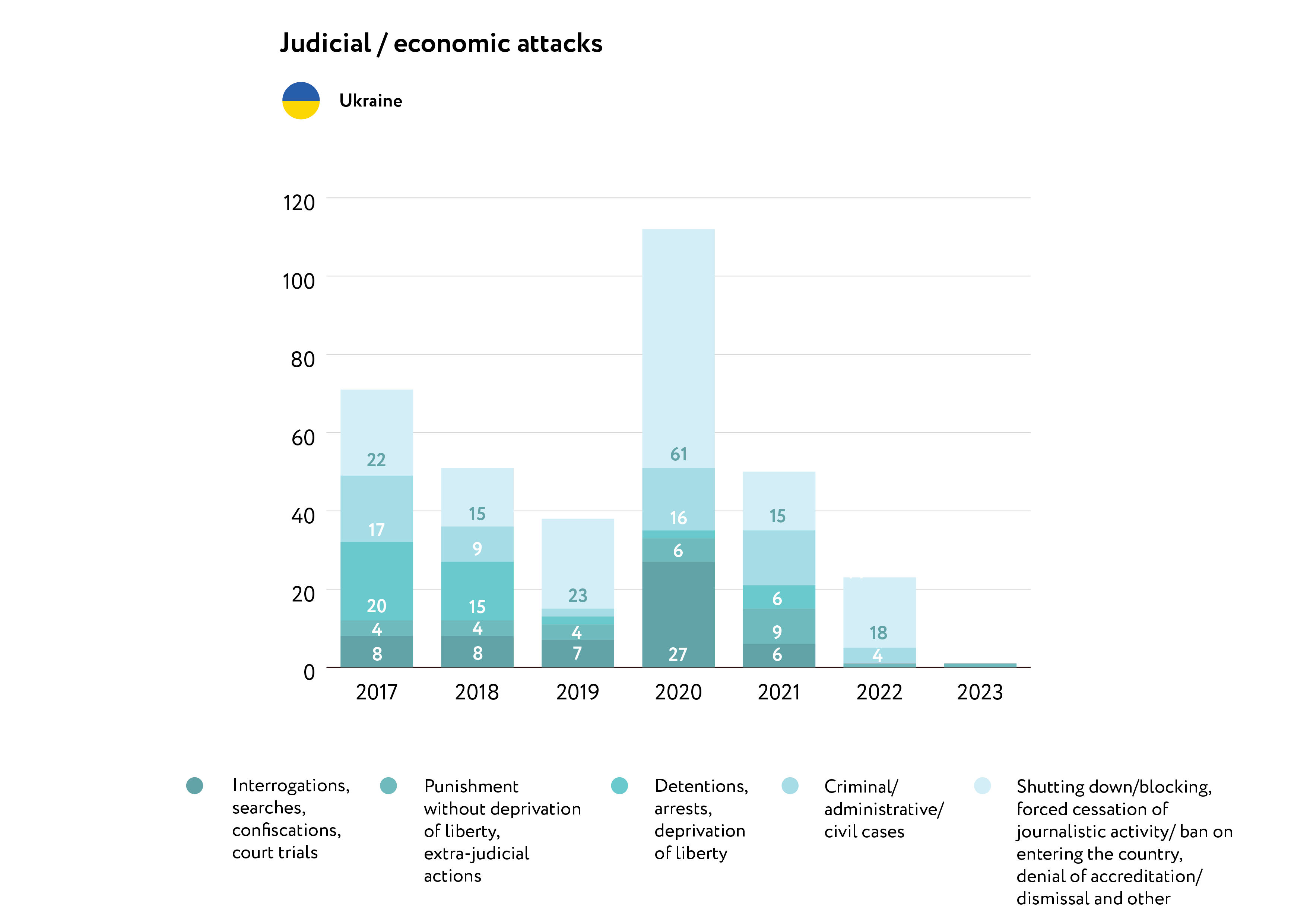

- In 2023, only one attack via judicial means was recorded in Ukraine. This case was not related to any representative of the authorities.

It is worth noting that not all information regarding threats and attacks of various types is made public, primarily because a significant part of the country’s territory remains under occupation. It is likely that after de-occupation, new information about any incidents that occurred in 2022-2023 will be revealed.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN UKRAINE

According to the 2023 annual rankings published by the international NGO “Reporters Without Borders”, Ukraine ranked 79 out of 180 countries, improving its position by 27 places compared to 2022. According to Reporters Without Borders: “The Russian invasion has had a major impact on the media, disrupting their work and threatening their economic survival. In territories under Russian control—Crimea, annexed in 2014, and regions occupied by the Russian army in 2022—Ukrainian media are often replaced by Kremlin propaganda.”

The second year of the Russian Federation’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has exacerbated the problems faced by the Ukrainian media. At present, the main problem in the industry is a shortage of staff. An increasing number of men have been mobilised into the Armed Forces of Ukraine and, as a result, are not able to continue their media work. At the same time, many journalists have opted to move abroad for their own safety, and the safety of their families. As a result, the number of media teams has significantly reduced, and many media outlets have shut down due to a lack of qualified personnel.

The only sources of income for the media are grants from foreign donors, and funding for covering the activities of government bodies (mainly applicable to local media). With this money, media outlets try to not only cover current expenses, but also to widen their channels to reach their audience by developing new websites, social media pages, and Telegram channels. The advertising market, including on the Internet, is showing more positive dynamics compared to 2022, but its volume and budgets are still not sufficient to guarantee the full functioning of the media.

From the first days of the full-scale invasion, a general information telethon called “United News” was launched on national television in order to promptly inform the population of Ukraine about the situation in the country. This source of information was both relevant and in demand in the first months of the full-scale invasion. However, over time, the quality of the marathon’s content began to deteriorate, and the information itself was often out of date. According to a survey conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology from May 2022 to December 2023, the percentage of those who consider the telethon a trusted source decreased from 69% to 43%.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

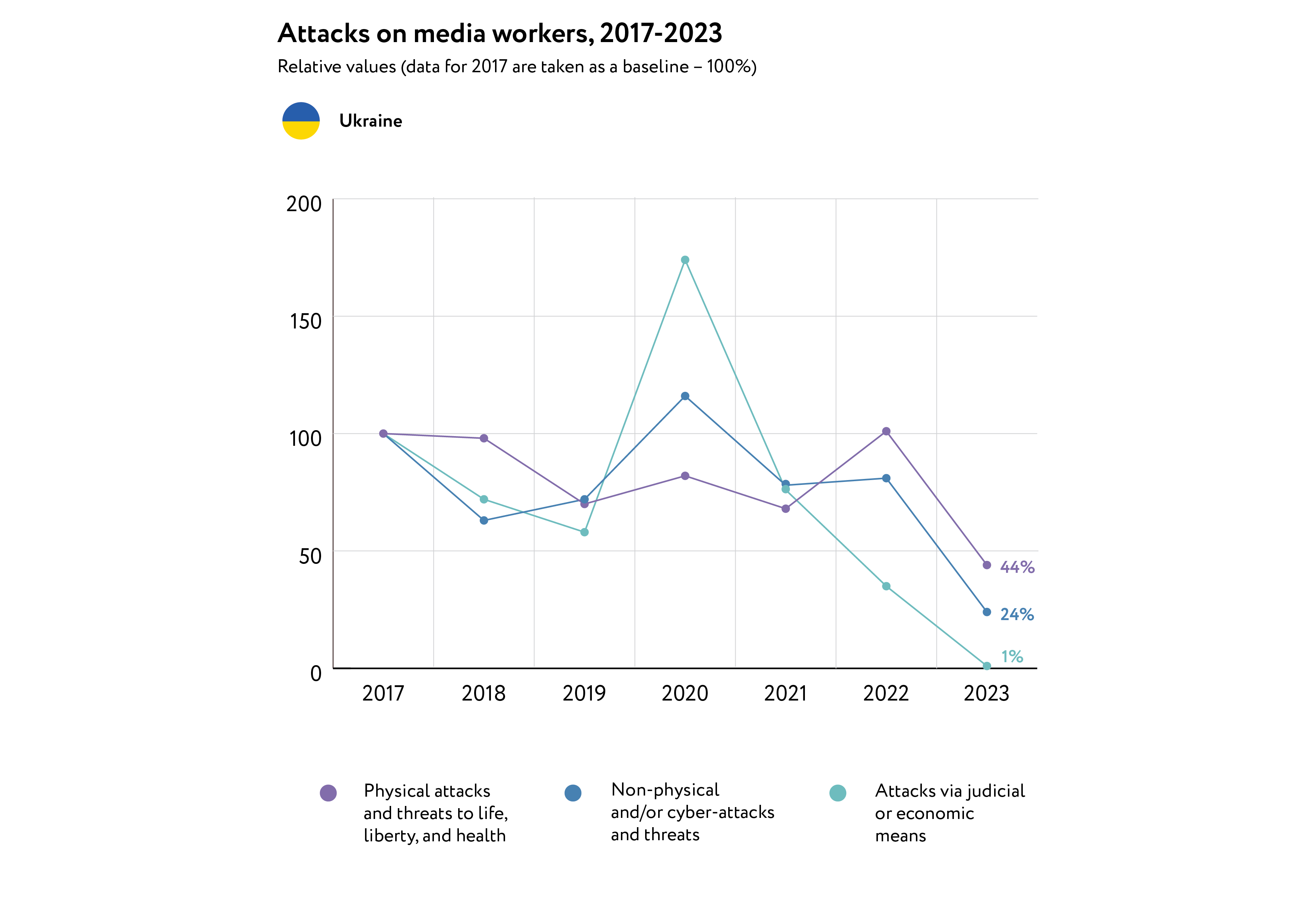

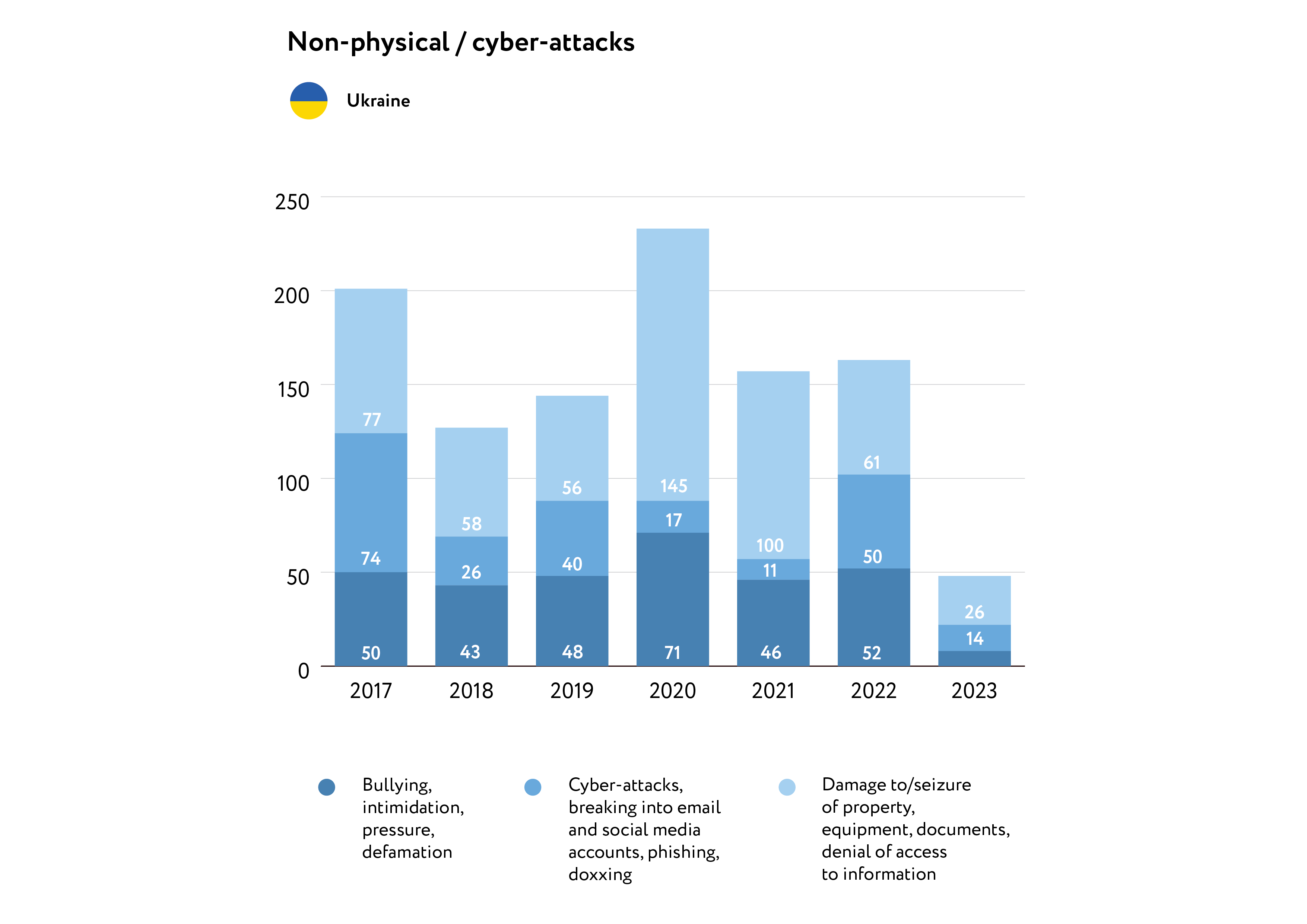

Between 2017 and 2019, there was a decrease in attacks against journalists, especially attacks via judicial and/or economic means. However, in 2020 this trend was interrupted due to local elections and restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, when the quarantine restrictions were eased, and the election campaign came to an end, the figures returned closer to 2019 levels.

The events of 2022 dramatically changed the lives of media workers in Ukraine. On 24 February 2022, thousands of Ukrainian journalists became “front-line” correspondents. At the same time, the full-scale war in Ukraine attracted the attention of foreign journalists, who promptly arrived in the country to cover the events firsthand.

2023 saw a record-low total number of incidents over the entire period of observation. In 2022, Ukrainian society united against an external enemy, and many internal disagreements were pushed aside, which protected journalists from attacks “from within.”

The graphs below represent the total number of physical and non-physical/cyber-attacks on media workers in Ukraine.

Additionally, by 2023, it became well known to all Ukrainian and foreign journalists that Russian troops were not complying with the rules of warfare, and that the status of “Press” did not provide for any protection for journalists. This has led to journalists working as carefully as possible in combat zones, avoiding breaking through the front lines to obtain information and sticking to the adopted mass media rules much more strictly than in 2022.

The Justice for Journalists Foundation, in partnership with the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine and with the financial support of UNESCO, has been collecting open-source evidence and satellite imagery of attacks on media workers during the war to create safety recommendations, risk assessments and HEFAT training for journalists heading to the war zone. Having analysed the collected data and interviewed the victims and witnesses of these attacks, JFJ has identified the key risks journalists face while reporting from the war zone and developed preliminary safety recommendations for media workers covering the war. These recommendations do not cover all aspects of journalists’ safety but are useful for those reporting from Ukraine.

According to the National Union of Journalists, at least 84 media workers (both Ukrainian and international) have died in the line of duty: 16 were killed while reporting, nine died as a result of collateral damage, and at least 59 journalists have died while serving in the armed forces.

Verified data confirms that 10 media workers have died as a result of enemy shelling. Among them are six foreign journalists: Arman Soldin, Frédéric Leclerc-Imhoff, Mantas Kvedaravičius, Pierre Zakrzewski, Oksana Baulina, Brent Renaud; and four Ukrainian journalists: Oleksandra Kuvshinova, Maks Levin, Bohdan Bitik and Yevhenii Sakun.

Additionally, at least four Ukrainian media workers were tortured and killed in Russian-occupied territories: Yevgeny Bal, Zoreslav Zamoysky, Roman Nezhyborets and photojournalist Ihor Hudenko.

4/ RUSSIAN WAR CRIMES AGAINST MEDIA WORKERS, COMMITTED IN UKRAINIAN-CONTROLLED TERRITORIES AS OF 24/02/2022

PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

In 2023, the Russian army continued to commit war crimes against media workers. Experts recorded and verified 42 incidents over the year. It is worth noting that this figure had fallen from 101 cases in 2022.

However, this decrease in the number of incidents does not suggest that Russian troops have begun to comply with the rules and customs of warfare. 2022 made it clear to Ukrainian and foreign journalists that the Russian aggressors were not abiding by these rules, so they needed to be as careful as possible while working on the front line. At the same time, the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, from the beginning of the full-scale invasion, made improvements to the rules for receiving accreditation and regarding the work of journalists on the front line. While these rules have certain restrictions, they were introduced to protect journalists and reduce the number of casualties.

Among the incidents recorded in 2023, 30 were attacks and threats of a physical nature, while 12 were attacks of a non-physical nature. It is worth noting that during this year there was not a single verified case of attacks via judicial and/or economic means. This is because invading Russian forces have further toughened their attitude towards media workers and primarily employ methods of physical pressure against them. In 2023, 4 cases related to the murder of media workers were recorded:

- On 26 April, the Antonovsky Bridge near Kherson came under Russian shelling. The vehicle with Corrado Zunino, a correspondent for the Italian newspaper La Repubblica, and his Ukrainian fixer Bogdan Bitik, came under fire. Zunino was wearing bulletproof body armour with the word “PRESS” written on it. According to him, Bitik was not wearing the same gear, was wounded and died from the injuries. The Italian government stated that the journalists came under drone fire. It is worth noting that the Ukrainian fixer and the Italian journalist ignored the military’s ban on filming in this specific area, and in addition, Bogdan Bitik was wearing an ordinary press vest, having left his bulletproof vest in the car.

- On 9 May, Agence France-Presse (AFP) video journalist Arman Soldin was killed during a rocket attack near the town of Chasiv Yar in the Bakhmut region. His film crew came under fire from Grad missiles around 16:30 Kyiv time. The rocket fell not far from where the journalist was lying. No other team members were injured. The French prosecutor’s office has opened a war crime case in connection with the death of Soldin. The Prosecutor’s Office of Ukraine is also investigating the case under Part 2 of Article 438 of the Criminal Code (“Violation of the laws and customs of war”).

- On 27 June, in Kramatorsk (Donetsk region), two foreign journalists were wounded during Russian shelling – British freelance photographer Anastasia Taylor-Lind and Latin American journalist Catalina Gomez. Ukrainian fixer Dmitry Kovalchuk, who worked for the Colombian media team and Gomez, also received minor injuries and emotional trauma. Ukrainian writer Victoria Amelina was also killed as a result of the same shelling incident. Together with a group of Colombian writers and journalists, she came to investigate the death of the Ukrainian writer and poet Vladimir Vakulenko, who was murdered during the Russian occupation of the Kharkiv area in 2022.

- On 25 September, freelance photographer Vladimir Mironyuk (also known as “WM Blood”) died as a result of his injuries after Russian drones attacked Ukrainian military positions. Mironyuk previously worked on a photo report about the Ukrainian Armed Forces in the village of Kurdyumovka. His photographs reflected real-time events and were often used by foreign and Ukrainian media.

In 2023, there were at least 25 attacks involving attempted murder and/or non-lethal attacks resulting from gunfire. Often such attacks were accompanied by pressure of a non-physical nature, such as the damage to vehicles used by journalists in combat zones:

- On 2 January, Björn Stritzel, a journalist for the German paper BILD, was injured in a Russian shelling attack on Druzhkivka (Donetsk region). Fortunately, the journalist was able to continue his work. “I’m fine, just a cut on my forehead, most likely from a piece of glass. I was having lunch when the explosion happened,” he wrote on Twitter.

- On 12 February, a film crew from the same German outlet – Paul Ronzheimer, Vadim Moisenko and Giorgos Moutafis, while working in Bakhmut, came under Russian mortar fire. The explosions were less than 200 metres from the journalists’ location. They eventually managed to reach shelter: “We ran away while explosions were still heard in the immediate vicinity. Sometimes it comes down to a matter of seconds, whether someone will be wounded or will survive.”

- On 22 July, Deutsche Welle cameraman Yevhen Shylko was wounded by Russian cluster munitions near Druzhkivka (Donetsk region), 23 kilometres from the front line. A DW film crew came under Russian fire while filming Ukrainian military training. Shylko was taken to the hospital; other members of the crew were not injured. The journalists’ car was also damaged by shrapnel.

- On 24 July, American AFP journalist Dylan Collins was wounded in a drone attack while preparing a report about Ukrainian artillerymen near Bakhmut. As a result of the attack, he received numerous shrapnel wounds. Collins was evacuated to a nearby hospital where he was given first aid.

- On 19 September, in Stephnohirsk (Zaporizhzhia region) a car containing the film crew from the Swedish TV channel TV4 was allegedly attacked by a Russian drone. As the journalists reported, on this day Johan Fredriksson and Daniel Zdolsek, together with Ukrainian producer Alexander Pavlov, arrived in one of the areas of the Zaporizhzhia region to film a piece about the Ukrainian counter-offensive. They were accompanied by two Ukrainian police officers who determined the filming location. According to journalists, one of the police officers heard the sound of a flying drone, so the entire film crew managed to leave the car before it hit. Members of the Swedish film crew were not injured, but Ukrainian producer Alexander Pavlov received minor injuries to his arm. The crew’s vehicle and equipment were destroyed in the attack.

- On 22 December, Russian troops shelled a section of the road in the Pokrovsky district, wounding two volunteers from a charity organisation and photographer Vlada Liberova. Their car came under fire as the team was travelling in the area documenting the consequences of Russian aggression. Liberova received shrapnel injuries, while two others were concussed.

- On 26 December, Reporters magazine editor-in-chief Marichka Paplauskaite came under Russian artillery fire at a railway station in Kherson. The journalist was working on material about heroic railway workers during the war and was preparing to board the train for Kyiv. Fortunately, she made it to a bomb shelter in time and was uninjured.

In 2023, targeted attacks on places with high concentrations of journalists continued. These included evacuation points, humanitarian convoys, hotels, and cafes in front-line cities. The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine notes that these tactics are widely used by the Russian armed forces to intimidate media workers.

- On 8 June, Russian artillery launched a targeted attack on a civilian evacuation point, where journalists were covering the evacuation of those fleeing the damaged Kakhovka hydroelectric power station. Shells exploded a few metres away from three Ukrainian journalists – “Bukvy” photographer Stas Kozlyuk, “Sledstvie.info” photographer Lyubomira Remazhevskaya and photographer from the online media “Grati” Stanislav Yurchenko. Fortunately, none of them were hurt.

- On 19 August 2023, Russian forces launched a missile attack on the Chernihiv Music and Drama Theatre while a group of drone manufacturers held a demonstration. Arsen Chepurny, a journalist for the online outlet “Chas Chernihivsky”, and cameraman Dmitry Falchevsky were covering the exhibition. Chepurny was wounded as a result of the missile attack.

- On 30 December, two of the five members of the film crew of the German TV channel ZDF were injured as a result of a Russian missile attack on the Kharkiv Palace Hotel, where Ukrainian and foreign journalists often stay. Producer Svitlana Dolbysheva and an unnamed security advisor were both injured.

The situation with regard to freedom of speech in the occupied territories has deteriorated significantly. Nearly all independent Ukrainian journalists were forced to leave following the full-scale invasion, and the few that remained are unable to continue their professional duties. The Centre for Journalist Solidarity of the NUJU tries to maintain contact with media workers in occupied areas via encrypted communication channels, and, where possible, assist with their evacuation.

According to verified data from the NUJU, two journalists were captured in 2023. Nothing is known about their current whereabouts:

- On 6 May, journalist Irina Levchenko and her husband Alexander were abducted by Russian troops in the Russian-occupied city of Melitopol (Zaporizhzhia region). Levchenko worked for many years as a reporter for various Ukrainian news agencies and was forced to stop her journalistic work after Russian troops occupied Melitopol in late February 2022. According to the Centre for Journalistic Solidarity of Zaporizhzhia (a regional department of the NUJU), after the arrest, the couple was kept in “inhuman conditions, with almost no food, in a cold basement, on a concrete floor” and was “subjected to physical and psychological torture.” On 30 May, Irina was transferred to another location, after which her whereabouts were unknown.

- On 3 August, Victoria Roshchina, a freelance journalist for “Ukrayinska Pravda”, disappeared in the Russian-occupied part of the Zaporizhzhia region. The journalist’s father claims that, according to Ukrainian special services, Roshchina was detained by representatives of Russian authorities and may be held in one of the Russian colonies. Speaking to the NUJU, the founder of the “Graty” media outlet, Anton Naumlyuk, said that the journalist managed to make it to the occupied part of the Zaporizhzhia region and after that, communication with her was lost.

NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

Among the verified cases of attacks of a non-physical nature, targeted attacks on the premises of editorial offices remain the most common, making up 7 out of 12 incidents. There were also 4 cases of journalists’ vehicles being shot at. Some of these incidents, which also included aspects of physical pressure on media workers, were described at the beginning of the chapter.

- On 17 January, during a Russian missile attack on Kherson, the editorial offices of the local newspaper and printing house “Debut-Gazeta” were destroyed. Fortunately, the incident occurred at night, so nobody was injured. However, given the extent of the damage, it is unclear whether the team will be able to resume operations.

- On 9 March, the office of the local Ukrainian radio station “Nastalik” (Nikopol, Dnipropetrovsk region), which also broadcasts in the occupied territories, was destroyed as a result of a direct missile hit. Most of the equipment was unsalvageable, and the cable that delivers the signal to the radio transmitters was also damaged. However, given the importance of independent broadcasters on the front line and occupied territories, and due to both the effort of the staff, and the support of the NUJU and foreign donors, work partially resumed within a few months.

- On 22 March, while working near the front line near a Ukrainian military position, the Donbas.Realii film crew came under fire from Russian mortars and Grad missiles. It is unknown whether this shelling was targeted at the press specifically, however, the film crew’s car was damaged by shrapnel. Fortunately, the journalists managed to hide in a trench and were not injured.

- On 23 March, as a result of Russian tank fire from the left (occupied) bank of the Dnipro River in Beryslav, the office of the local newspaper “Mayak” was damaged. The newspaper staff had already been forced to evacuate soon after the beginning of the full-scale invasion, so there were no casualties.

- On 30 August, a Radio Liberty film crew came under missile fire in the Donetsk region. Journalists Evgenia Kitaeva and Anna Kudryavtseva and their local driver Vladimir Yavnyuk were not harmed, but the crew’s vehicle was damaged.

- On 6 October, during a targeted missile attack on the “Reikartz” hotel in Kharkiv, the car of the film crew of the Portuguese TV channel RTP was heavily damaged. The journalists were not injured. It is worth noting that this hotel was very popular among journalists and representatives of various international organisations during their business trips to Kharkiv.

- On 6 October, the office of the local media outlet “ATN” was damaged during a missile attack in the centre of Kharkiv. None of the employees were injured.

- On 30 December, during a massive missile attack on Kharkiv, the offices of three local media outlets were damaged– the “Ukrainian Radio Kharkiv”, the National Public TV and Radio Company of Ukraine and the Objective Media Group.

Following a huge increase in the number of cyber-attacks in 2022, Ukrainian media significantly strengthened their defence mechanisms which led to a decrease in damage related to cyber-crime in 2023. Analysing the nature of the attacks and their connection to military events, there is reason to believe that Russian hackers are behind at least eight cyber/DDoS attacks as well as some hacks from “unknown” origins. This conclusion is supported by the fact that during these attacks, pro-Russian narratives appeared on the hacked websites. Such incidents include:

- On 17 January, the website of the largest news agency in Ukraine, “Ukrinform”, was subject to a cyber-attack. However, the agency continued to reach its audience on social media, and IT specialists were able to quickly fix the issue. Specialists from the Ukrainian computer emergency response team CERT-UA, operating under the State Special Communications Service, investigated the cyber-attack and discovered messages on the Russian Telegram channel “CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn” where hackers “bragged about their success” in the attack on “Ukrinform”.

- On 1 March, cyber-criminals tried to hack and penetrate the airwaves of the regional radio station “FM Galicia”. According to the Security Service of Ukraine, the attack was carried out by Russian hackers. Before the attack, there was a post published on the “People’s CyberArmy” Telegram channel saying: “Good evening, Cyber Army! We’re working on the radio again. The target is Radio “FM Galicia”.

- On 11 May, the website of the national television channel “Channel 24” was subject to a cyber-attack. According to the outlet’s representatives, this attack was ordered by Russia. Immediately after the hack, threats to Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Ukrainians with narratives similar to the Russian IPSO (informational psychological special operation) began to appear on the site. Also, not long before the attack, the “Channel 24” website was due to publish an investigation about a Russian GRU (Main Intelligence Directorate) agent.

- On 25 May, the Russian hacker group “Solntsepyok” attacked the website of the online outlet “Evening Kyiv”. Several fake news stories were published, bearing the site’s logo. At the same time, according to the outlet’s representatives, the hackers were unable to gain access to the server or database.

- On 9 August, the ZN.UA website was subjected to a DDoS attack by Russian hackers, which prevented readers from accessing the site for several hours. Technical support managed to promptly restore the access.

- On 20 August, Russian hackers took over the Telegram channel of the independent Ukrainian media “RIA-Melitopol”, which was previously a source of objective information for people in occupied Melitopol. The team of the independent outlet was forced to create a new Telegram channel “RIA-Pivden” after the previous incarnation became a Russian propaganda channel.

- On 15 October, the website of the NUJU was subjected to a significant DDoS attack by Russia. As a result, the resource was unavailable all day. Later the hosting provider received a request from the Russian watchdog Roskomnadzor (Russian Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media) to block access to the website due to “non-compliance of its content with Russian legislation.”

- On 7 November, Russian hackers attacked the “United News” telethon by hijacking the satellite signal. For around an hour, Ukrainian viewers noticed that the broadcast was interrupted by Russian music videos and propaganda.

5/ ATTACKS ON MEDIA WORKERS BY UKRAINIAN AUTHORITIES, CIVILIANS AND UNKNOWN INDIVIDUALS (NON-WAR-RELATED INCIDENTS)

In 2023, the number of attacks initiated by government officials, non-government officials and/or unknown individuals hit a record low. Only 10 incidents involving physical attacks on media workers were recorded. Six of them occurred during the coverage of events related to the transition of religious communities from the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-PM) to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. These incidents include:

- On 29 March, “Suspilne” journalist Daria Nematian Zolbin, “Suspilne” cameraman Viktor Mozgovoy, “Pryamiy” TV journalist Andrey Solomka, “Pryamiy” TV cameraman Anton Puzan and Espreso TV journalist Valeria Pashko faced physical violence and obstruction of their work at the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra Monastery. 29 March was the deadline for the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate to leave the monastery premises after its lease was terminated and the complex was submitted to direct state control. Worshipers and priests behaved aggressively towards journalists and made efforts to interfere with their work.

- On 9 May, residents of Poltava came to lay flowers at the Soldier’s Glory Memorial. Journalist Tatyana Tsirulnik was covering the ceremony when an unknown man began to aggressively demand that she leave, pushing her and hitting her in the face. Poltava police opened a criminal investigation into violence against the journalist.

- On 11 May, journalists from the National Public TV and Radio Company of Ukraine – journalist Oksana Shved and cameraman Sergei Efimov – arrived at one of the local churches to cover the parish’s voting on the transition from the Russian Orthodox Church to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. Supporters of the Moscow Patriarchate aggressively obstructed the work of the journalists and attempted to cover the camera lens with their hands. The police opened a criminal case into obstructing the work of journalists.

- On 8 June, the head of the OSBB (an association of co-owners of an apartment building) incited a conflict with journalist Vadim Tomashevsky, who is a tenant in one of the block’s apartments. The head of the OSBB struck the journalist in the jaw. Tomashevsky filmed the attack and submitted his complaint to the police. The incident occurred during an air raid. Tomashevsky and his filming crew had to seek shelter in an underground car park, where they carried on with their work. However, the building’s security and the head of the OSBB insisted that the journalists were filming a story about their housing company and took aggressive measures to stop it.

- On 29 June, Maxim Tkachenko, a photographer for the outlet “18000”, was filming in one of the local cathedrals, where parishioners were divided in their loyalties between the Russian Orthodox Church and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. The supporters of the Moscow Patriarchate barricaded themselves in the cathedral and refused to let anyone in, including journalists. Tkachenko was filming at the gates when an unknown individual assaulted him and tried to damage his camera. During the incident, the camera microphone broke off, but later it was returned to the journalist.

- On 12 July, Vladimir Sedov, a photographer for the “Vesti Ananyevshchiny” newspaper, was attacked. He was struck in the head and lost consciousness. When he woke up, he felt severe pain in his hands. He underwent a medical examination and filed a police complaint. According to Vladimir, this incident is directly related to his journalistic work: he closely covers the activities of allegedly corrupt local authorities.

- On 17 November, the work of investigative journalist Mikhail Tkach and his team from the publication “Ukrainska Pravda” was obstructed by security guards of one of the visitors to a restaurant in the elite village of Kozyn near Kyiv. Reporters came to the restaurant after spotting the cars of several former senior officials from the Attorney General’s Office in the car park. When the personal security of one of the high-profile visitors noticed that journalists were filming them, they blocked their cars in the car park. One of the security guards assaulted Tkach and tried to damage his phone.

There have typically been high numbers of attacks of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks in Ukraine: 14 out of 36 of these incidents were related to cyber-security. One case involved the hacking of the Google account of the regional online media “Fourth Estate” (Rivne City). It is assumed by journalists and cyber security experts that the attack could have been carried out by a local resident, who was involved in a number of investigations.

In addition to cyber-attacks, journalists were subjected to other attacks of a non-physical nature, the most significant of which include:

- On 9 March, a journalist from the local online media “Gard.City” (Pervomaisk, Mykolaiv region), Natalia Klimenko, revealed that she was facing pressure from the mayor of the city of Pervomaisk Oleg Demchenko, after the publication of an article about a city council meeting, during which the mayor’s salary was discussed. Mr Demchenko began calling the journalist and accusing her of bias. It is worth noting that several local journalists have previously reported threats and pressure from the mayor.

- On 21 May, the film crew of the TV channel “Konkurent TV” – journalist Olga Voznyaki and cameraman Alexander Fetisov – arrived in Lutsk to work on a story about the “Veloden” cycling event hosted by the city administration that day. The parking lot of one of the local shopping and entertainment centres was chosen as the starting point for the participants. The entertainment centre’s security guards obstructed the journalists, citing private property rules and martial law in the country.

- On 29 March, Anastasia Matsko, a journalist for the “Poltava Wave” (Poltava), stated that two officials in the city council building threatened her with physical harm and rudely expressed their dissatisfaction with her published work.

- On 30 March, in Chernihiv, a local businessman Sergei Berestovy began to threaten the film crew of the “Ditinets” TV and Radio Broadcasting Company – journalist Natalya Medvedeva and cameraman Andrey Lisun – when they tried to get a comment from city council deputy Yuri Tarasovets, who was in the cafe with him. The attack was not only verbal, as Berestovy also broke the crew’s camera.

- On 23 June, employees of the Odessa Regional Council did not allow journalists from the local media outlet “Dumskaya.Net” – Oleksandr Gimanov and Vitaly Prus – to cover the council’s session. The order to do so came from the head of the legal department of the council. According to the journalists, this ban was related to their critical publications about this individual and other deputies.

In addition to the illegal obstruction of journalistic activities, this year also saw cases of damage to journalists’ property for the purpose of intimidation. Such cases have become increasingly common in Ukraine:

- On the night of 15 June in Rivne, unknown individuals set fire to a car that belonged to the editor-in-chief of the “Western Argument” news agency, Vlad Isaev. Isaev claims this is due to journalistic work.

- On the night of 16 June in Kostopil (Rivne region), unknown individuals set fire to the home of the former editor of the Kostopil regional newspaper, and founder of the Facebook group “Our Kostopil” Alexander Namozov. The attackers gained entry to the garden, used a taser on his two dogs, doused the house with fuel and set fire to it. Fortunately, the owner managed to escape. He suspects the leadership of the Kostopil City Council organised this attack.

- On 6 November, in the city of Brovary (Kyiv region), unknown individuals set fire to journalist Nikolai Pastukh’s apartment door. He doesn’t know who was behind the attack.

At least eight incidents related to the intimidation of media workers were recorded:

- On 5 March, the admin of the local Telegram channel “Pervomaisk City” Dmitry Ivanitsky made a public statement about the threats he had been receiving from the mayor of Pervomaisk, Oleg Demchenko, after information regarding an increase in the mayor’s salary and the possible misappropriation of funds was published on Telegram. Demchenko does not deny his conflict with Ivanitsky but claims that the real cause of this situation was Ivanitsky’s wrongdoing. According to the mayor, Ivanitsky, who is the former head of the city’s press service, maintained access to all of the city council’s social media pages after leaving his job.

- On 11 May, the film crew for “Espreso” TV was working on a story about real estate belonging to judges. While filming in one of the apartment buildings, a man, who said he was renting a flat from a judge, behaved aggressively towards them. He snatched journalist Maria Ivanovskaya’s phone and threatened to assault her. A complaint regarding the incident was filed with the police.

- On 12 July, after an article about difficulties facing the LGBT community in Sumy was published on the “Tsukr” website, calls to set fire to their office began to appear on the Internet, along with their address. Police began criminal proceedings in connection with these threats.

- On 18 September NGL.media received a threatening email. This is thought to be in connection with a journalistic investigation about a number of men illegally avoiding military service by fleeing Ukraine after the start of the full-scale invasion.

In 2023, one attack via judicial and/or economic means was recorded:

- On 27 June, Anastasia Venislavskaya, co-owner of the Lutsk-based company “Spetskommuntech”, filed a police report against the Centre for Investigative Journalism “Power of Truth”. This was due to an investigation into her company’s involvement in a fraud scheme. The journalists repeatedly tried to get a comment from Venislavskaya, so her side of the story could be reflected in the article. However, she refused to comment and later filed a complaint with the police.

ANNEX 1: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (UKRAINE)

- National Union of Journalists of Ukraine – the largest organisation uniting journalists and other representatives of mass media in Ukraine.

- National Council of Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine – constitutional, constantly operating collegial public authority that aims at observance of Ukrainian legislation in the sphere of television and radio broadcasting, as well as at exercising regulatory powers prescribed by respective laws.

- Online resources of the National Police of Ukraine.

- “Ukrinform” – Ukrainian state national news agency

- “Ukrainian News” – one of the largest private news agencies in Ukraine

- The ZMINA Human Rights Centre – a Ukrainian non-governmental organisation that concentrates on protecting freedom of speech, and supports human rights and civil rights activists in Ukrainian territory, including occupied Crimea.

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty – international non-profit radio broadcasting organisation.

- Facebook and Telegram

- Open-source media in Russian and Ukrainian; accessible on the Internet.