This investigation is part of the Justice for Journalists Foundation Investigative Grant Programme and was originally published by The Cable).

The nation was shell-shocked in April 2017 when operatives of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) discovered $43.4m, among other currencies, in the wardrobe of a four-bedroom apartment in Ikoyi, Lagos. Videos and photos of the sting operation shared by the anti-graft agency were similar to scenes from a raid of the stash house of a drug cartel. The EFCC credited a whistleblower’s confidential alert for the huge recovery. That moment represented a shift in the anti-corruption efforts of the federal government and encouraged whistleblowers to come forward with valuable information. But while the government has made several recoveries, how have the whistleblowers fared? In this report, DYEPKAZAH SHIBAYAN examines how the fight against corruption has put the lives of whistleblowers at risk and why a policy meant to encourage and protect them is failing in Nigeria’s long-drawn-out war against graft.

BLOW THE WHISTLE, FACE PERSECUTION

Citizens aspiring to get into public service seek to have a successful career and earn a living to take care of their families. Most intend to spend either 35 years in service or attain 60 years of age to retire from their careers in line with the public service rules.

However, those who have the guts to openly fight corruption within their organisations are often persecuted, dismissed and left in a state of despair. Joseph Akeju, a former bursar at the Yaba College of Technology in Lagos state, found himself in this boat when he travelled the lonely road of whistleblowing a few years ago.

Akeju would have loved to be able to adequately support his family and have a fulfilling career before retiring from service – but that was not his lot.

The former bursar said he first ran into hot waters when he first refused to partake in a “loot” in 2009. Akeju said he was eventually dismissed for his “principled stance” and after seven and half years of despair, he was reinstated by Adamu Adamu, the minister of education, in 2016.

He said during the process of trying to get his job back, providing for his family became herculean while some people benefited from his plight.

“This story was quite sensational. Some press people were using my name to eat. Some of them went to my then-boss to go and collect money from him,” Akeju told TheCable.

“They twisted my position, my words and it became a lot of crisis. They were pursuing me with juju up and down. I just thank God that those things are past.”

After he was reinstated, Akeju was transferred from the college to the Federal Aviation Authority of Nigeria (FAAN). The lecturer said the college was financially healthy when he left for FAAN and upon his return after two years, he found out that the institution was broke and borrowing.

“I left for another assignment at FAAN, I was taken there as the director of finance and I had to leave Yaba College of Technology as bursar,” he said.

“Before I left there was a lot of money. After two years when I came back to the college, we were borrowing. Students were suffering and I looked into our finances [and saw] that frivolous contracts were given.”

The former bursar said he then raised the alarm that the staggering sum of N1.6 billion was missing, prompting his second dismissal from service. The sum, he alleged, was diverted between 2008 and 2014.

‘I LOST EVERYTHING’

Before his second dismissal, Akeju said his life was threatened through diabolical means by the people connected to the alleged fraud that he blew the whistle on.

“The threat to life was there and it did not come physically but you know the Nigerian way of making you scared, I became very sick,” he said.

“I was always sick. It is through the grace of God [that I survived]… I lost everything.”

Amidst the ordeal, Akeju said he lost his mother, a wife, and could not afford to pay the school fees of his children.

“I lost my mother, I could not bury her in the [morgue]. Up till now I have not been able to balance up [payment], it was around that time I lost my junior wife. I had to stop the education of my children. I couldn’t fund their schools and it is still affecting me till today,” he said.

“The governing council didn’t want to listen to me. They just cooked up stories and dismissed me.”

COURT BATTLE… THEN SOFT LANDING

While out of a job yet again, the debts piled up for Akeju, especially because he was in court for more than eight years trying to get justice.

“A new person was elected as rector and gave me a soft landing. They paid me depreciated money. The money they gave to me had already lost value and I was paying debts that I had already incurred,” he said.

“After I was reinstated, some of the people that persecuted me were still there.

“They wanted to deal with the woman who brought me back, I resisted and they dismissed me.”

He said the letter conveying his third dismissal was delivered to him while he was temporarily bedridden in the hospital. The letter came at the time when Lateef Fagbemi, a senior advocate of Nigeria (SAN), was head of the governing council of the college.

“People are wicked. I was in the hospital when they dismissed me. They brought the letter to me in the hospital. God saved me,” the former bursar said.

Akeju said one of his former students helped him file a petition at the school’s senate, and he was subsequently reinstated, but it was too little too late as he was almost due for retirement.

“I do not have anything. I haven’t recovered from it,” he said almost in tears.

‘SACKED FOR EXPOSING FRAUD’

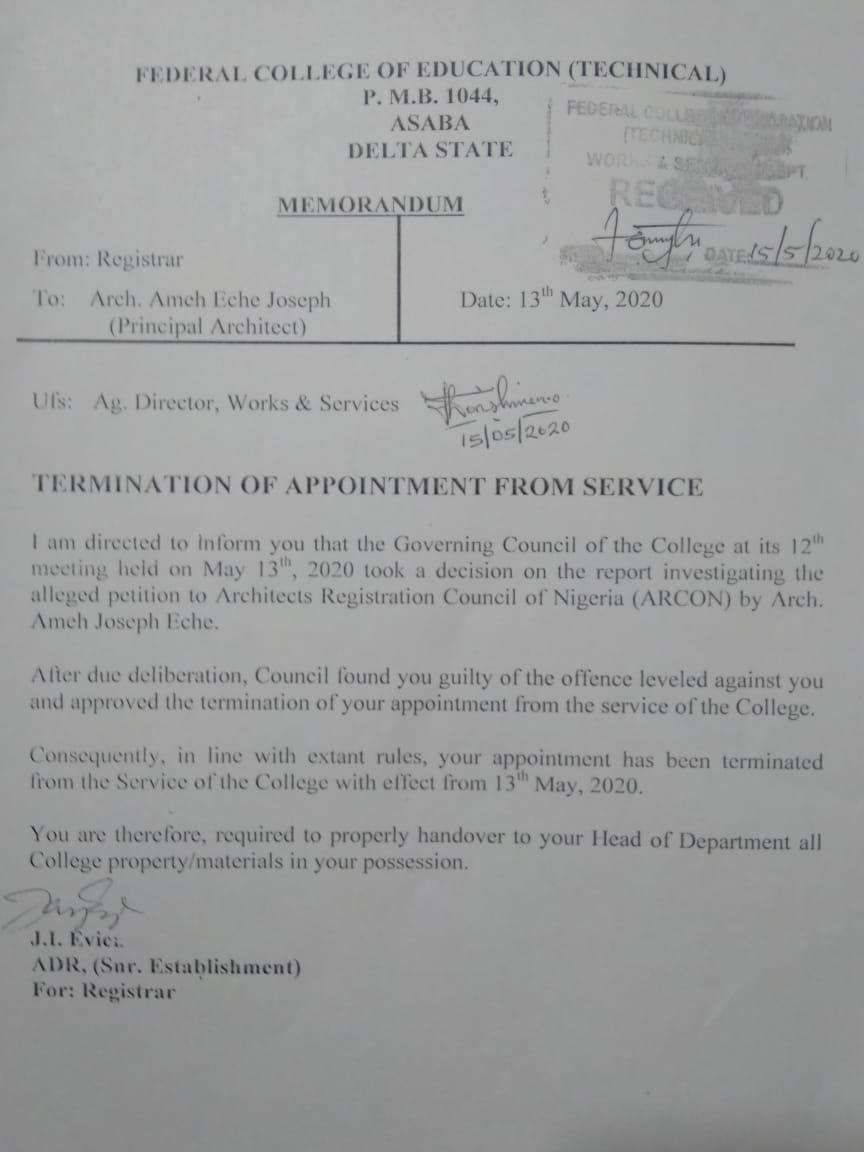

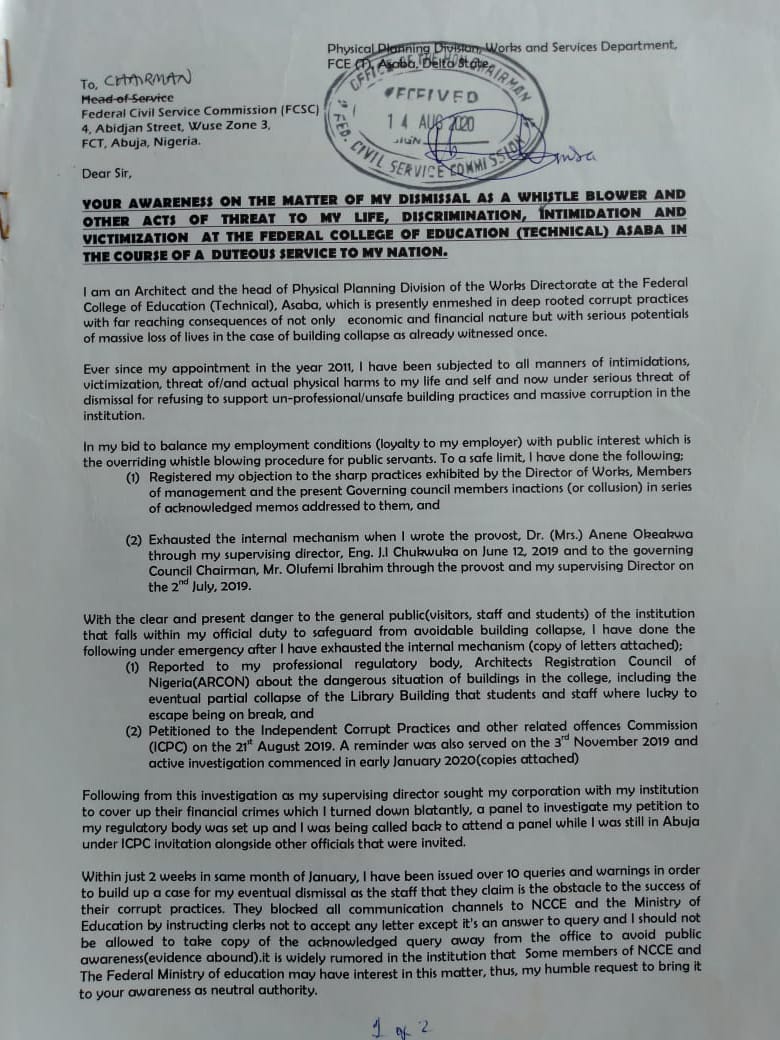

In 2020, Joseph Ameh, an architect with the Federal College of Education (Technical), Asaba, Delta state, was sacked after petitioning the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission (ICPC) about alleged contract fraud in the institution.

Until his sack, Ameh was head of the physical planning division at the institution, where he had worked for 10 years.

In his petition to the anti-graft agency, the architect alleged that over N60 million – voted for 12 projects – was diverted by the management of the institution.

“One of the members of the visitation panel from the federal ministry of education said what they had put into that institution in the past three years was over N15 billion but he did not see anything that looks like N3 billion there,” Ameh said.

The architect said he got wind that the college was planning to sack him over his petition and he informed the ICPC so he could be protected.

Ameh said Mohammed Lawal, ICPC’s lead investigator on his case, advised him to seek the intervention of the Architect Registration Council of Nigeria (ARCN).

He was fired after the ARCN weighed in on the case.

His sack letter reads in part: “I am directed to inform you that the Governing Council of the College at its 12th meeting held on May 13th 2020 took a decision on the report investigating the alleged petition to Architects Registration Council of Nigeria (ARCON) by Arch. Ameh Joseph Eche.

“After due deliberation, the Council found you guilty of the offense levelled against you and approved the termination of your appointment from the service of the College.

“Consequently, in line with extant rules, your appointment has been terminated from the Service of the College with effect from 13th May, 2020.”

‘ICPC FAILED TO PROTECT ME’

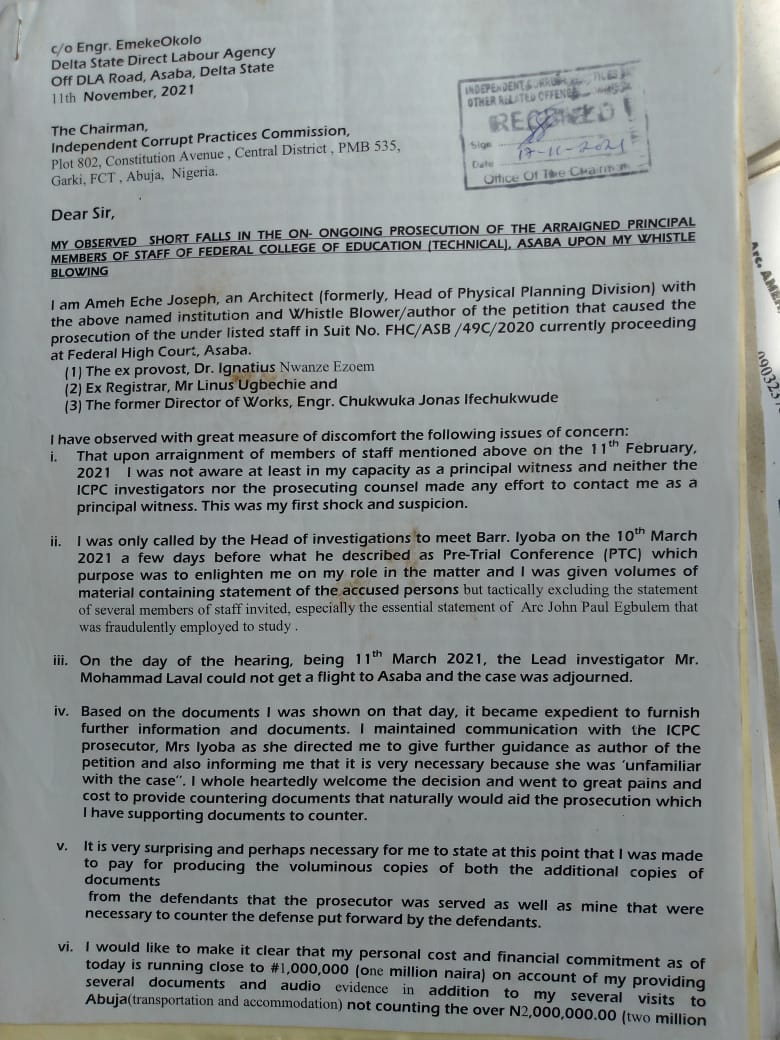

Ameh did not hide his identity when he petitioned ICPC, but he, however, wonders how those he accused of malpractice got to know of the petition and eventually forced him out of the system.

“ICPC exposed me. The petition I did, I did not hide my identity. I gave my identity because I’m 100 percent sure of what I am saying,” he said.

“The ICPC is not supposed to put my name out there but the people I accused already knew me and that was how I was victimised.”

Members of college management who were found culpable of malpractice were arraigned by the ICPC but they were later discharged over “faulty prosecution”.

“Concerning me having to testify, they refused,” he said.

“Until the last day of entertaining witnesses, the SAN, Femi Falana, put a call to the ICPC office to say that it was wrong. I wrote a letter to ICPC that since they refused to allow me to testify in court, I would testify in public.”

Ameh claimed that the documents he gave the ICPC lawyers were rejected and never tendered in court as exhibits.

The accused – Ignatius Ezoem, provost; Ugbechie Linus, registrar; and Chukwuka Jonas, director of works – continued their duties while the case was ongoing.

They would later retire from service.

Letters written to President Muhammadu Buhari and the Federal Civil Service Commission by Ameh did not yield any result.

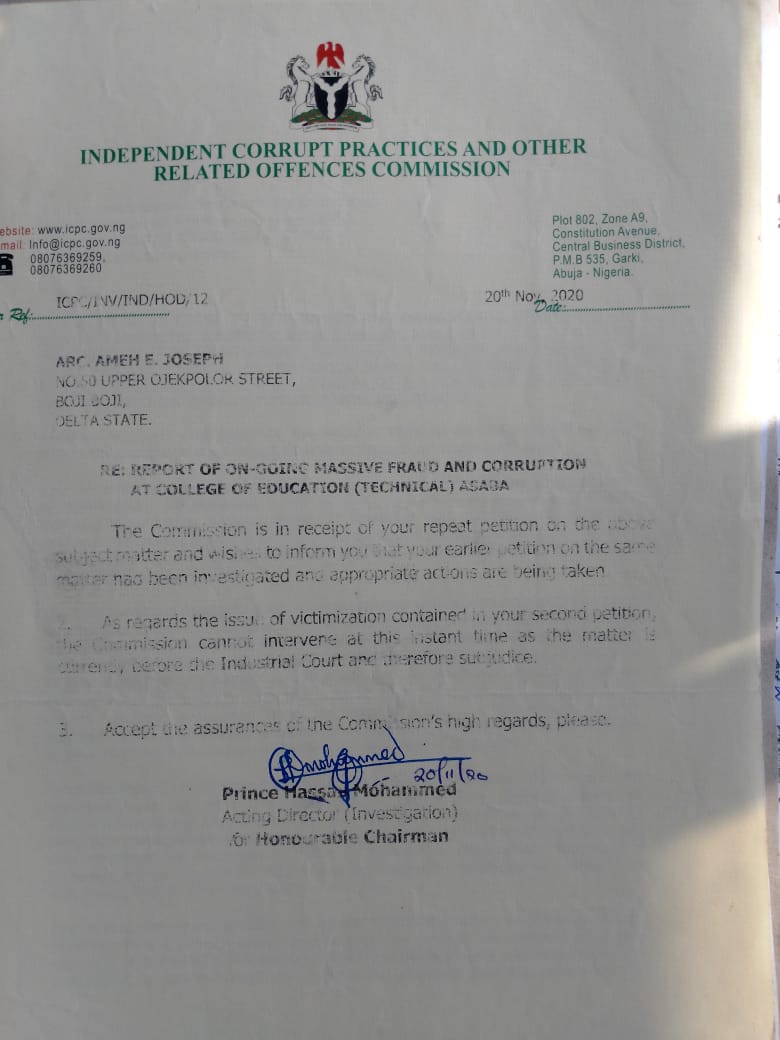

In a correspondence seen by TheCable, the ICPC said it could not intervene in Ameh’s claim of victimisation because the matter was before the industrial court, “thereby subjudice”.

When contacted Azu Ogugua, ICPC spokesperson, asked that a message be sent. After that was done, Ogugua never reverted.

The ordeal also took a toll on Ameh’s relationship with his wife after she got in contact with a cleric over his plight.

While Ameh was battling his sack, his wife Rosemary got introduced to Israel Ogaga, a prophet, who allegedly told her that if she returned home, either she or her husband would die in three days.

The architect said the prophet claimed that his ordeal was “spiritual”.

“I still wonder what and where lies the interest of the pastor in breaking and putting a family and marriage asunder,” Ameh, a father of three, said in a petition dated August 11 and addressed to the Delta state commissioner of police.

When contacted, Ogaga denied the allegations levelled against him.

“I’m a clean man. I don’t have anything in my cupboard,” he said.

“The way you are now, somebody says he takes your wife. It is even shameful for you to cry that someone took your wife from you and you are a man. I am a happily married man and I have a wife.”

‘NIGERIANS LOSING INTEREST IN WHISTLEBLOWING’

In 2016, the federal government launched a whistleblowing policy, domiciled in the federal ministry of finance, in an effort to tackle corruption.

The policy seeks to compensate whistleblowers for exposing corruption.

Notably, in 2017, the policy brought in some influx of cash after the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) said it discovered $43 million, £27,000 and N23 million stashed away at a flat in Ikoyi after a tip-off from a whistleblower.

In June 2022, the president said around $386 million was recovered in 2021 through the whistleblowing policy.

However, the number of willing whistleblowers is said to be on the decline.

Abdulrasheed Bawa, EFCC chairman, attributed the drop to “false whistleblowers who were prosecuted for wanting to turn a serious programme to memes, unnerved some other would-be informants”.

Similarly, Zainab Ahmed, minister of finance, budget and national planning, said Nigerians are losing interest in whistleblowing. “After about two to three years of the implementation of the policy, the interest of the public and the policy began to nosedive,” the minister said in July 2022.

Experts believe that apathy towards whistleblowing might encourage sustained corruption in the civil service.

In September 2022, the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) said the biggest cases of corruption are allegedly perpetrated by civil servants.

Ahmed Idris, a suspended accountant-general of the federation, is currently being prosecuted by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) for alleged N109 billion fraud. Also, the trial of Abdulrasheed Maina, a former civil servant who is accused of embezzling billions of naira in pension funds, is still ongoing after several years.

FAILED LEGISLATIONS

Questback, an online survey and feedback software company, said many people believe that the global best practices for whistleblowing must have protection, incentives, legislation and an easy way to report or expose corruption in place for those interested in ridding society of malpractices.

It said the anonymity of the whistleblowers – who might be afraid of the loss of their jobs or the threat to life – is valuable in the fight against corruption.

The eighth senate led by Bukola Saraki passed the Whistleblower and Witness Protection Bills separately.

But the whistleblower bill got stuck during the second reading in the house of representatives and did not make it through to a third reading by the time that assembly wound down.

The legislation sought to protect whistleblowers against victimisation and loss of jobs.

In 2019, under the senate led by Ahmad Lawan, the Whistleblower and Witness Bills were consolidated and reintroduced as one single legislation.

However, Benjamin Uwajumogu, senator representing Imo north and sponsor of the bill, died a month after he reintroduced it.

After his demise, nothing has been heard about the bill.

In December 2022, the federal executive council (FEC) approved a new whistleblowing bill to be sent to the national assembly for consideration and subsequent passage.

With only a few months to the end of the ninth national assembly, the prospect of having a whistleblower bill materialise is not encouraging.

BUT LEGISLATION IS STILL THE SOLUTION

The African Centre for Media & Information Literacy (AFRICMIL), a civil society organisation (CSO) dedicated to the protection of whistleblowers through its Corruption Anonymous programme, has been working to obtain justice for Akeju and Ameh.

In a survey published in 2021, AFRICMIL said whistleblowing has had little impact in tackling corruption owing to some challenges – lack of legal protection for whistleblowers, prolonged periods of investigation and delay/miscarriage of justice.

Kola Ogunbiyi, AFRICMIL programme manager, said adequate legislation would better protect whistleblowers and encourage them to expose corruption. He said the national assembly should ensure that it works on the bill and transmit it to the president for assent before it winds down in June.

“Having realized the challenges faced by whistleblowers and having realised the decline in whistleblowing because of the absence of legislation, I think the way forward is to advocate rigorously for legislation before the end of this administration,” he said.

“When they come back [from the elections] we still have about two months before the end of the administration.”

Amnesty International also believes that the absence of a law protecting whistleblowers has rendered the policy weak.

“It is imperative that the legislators pass the Whistleblower Protection Bill into law and present it for the president’s assent before this administration’s cycle ends,” Osai Ojigho, director of Amnesty International Nigeria, told TheCable.

“Anti-corruption human rights defenders – journalists, members of civil society organisations, whistleblowers, and others – play a crucial role in the prevention of and in the fight against corruption and the promotion of human rights.

“Over the years, they have been instrumental in investigating and exposing corrupt practices and in demanding transparency and accountability and the protection of human rights.

“The government has a responsibility in line with international standards to protect human rights defenders and foster an environment that allows them to thrive.”

Although Akeju and Ameh do not have regrets about exposing corruption at the organisations they worked for, the ripple effects of their actions have adversely affected them and altered the course of their lives.