Editor’s Note: This story is part of a special project by the Kyiv Post, “Dying for Truth,” a series of stories documenting violence against journalists in Ukraine. Since the country gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, more than 50 journalists have been killed across Ukraine — including eight since 2014. Most of the crimes have been poorly investigated, and the killers remain unpunished. The project is supported by the Justice for Journalists Foundation. Content is independent of the donor. All the stories in the series can be found here.

The article was originally published on the Kyiv Post website. Cover photo by Ukrinform.

Most Ukrainians remember the “dashing 1990s” as a hard time of economic and political crisis fueled by unstoppable gang wars that erupted across the country.

In a post-communist power vacuum, with democrats not yet solidifying control, the newly independent country was falling apart, Yulia Mostova, the chief editor of the Dzerkalo Tyzhnya news website, remembers.

Some regions of the country were controlled by local criminal gangs constantly fighting for power. Almost every week Ukrainians read news stories about another criminal boss killed either by his mafia counterparts or the police.

Despite the brutality surrounding them, Ukrainian journalists finally felt freedom. Soviet censorship had vanished, and the Ukrainian government had not yet managed to create its own, Mostova told the Kyiv Post.

“So it was a time when the new Ukrainian journalism was born. It was fast, furious and balanced, with all sides present in the story. We were learning new formats and ways of freedom of speech,” she said. “A new generation of fearless and unstoppable journalists appeared in Ukraine. They dared to write about everything despite the period: bandit years with bandit methods for dealing with journalists.”

Indeed, many journalists paid dearly for their newly obtained freedom of speech.

The Committee to Protect Journalists lists only three Ukrainian journalists murdered for their profession between 1992, when the media watchdog started collecting data, and the end of the decade. But independent reporting has revealed at least 17 journalists who died under unusual circumstances during the 1990s in Ukraine.

Police qualified most of these killings as street attacks, tragic accidents or suicides. However, in many cases, colleagues and relatives of the victims were confident that police had reached false conclusions.

Such is the story of Petro Shevchenko, a Luhansk-based correspondent for Kievskiye Vedomosti, independent Ukraine’s first private newspaper, founded in 1992.

In 1997, Shevchenko was found hanged in an abandoned boiler room in the Kadetsky Hay district of Kyiv. Police called his death a suicide, but Yevhen Yakunov, the newspaper’s chief editor in the 1990s, still thinks that, if it was a suicide, someone might have forced one of his best journalists to end his own life. Police never found out whether that was true.

Shevchenko’s case

Yakunov remembers the 1990s as a time when journalism finally became a respected profession in Ukraine. Newspapers quickly became the most important source of information for the public, rather than tools of propaganda like they were in the U.S.S.R. Suddenly, reporters were able to criticize politicians and officials freely and write about anything they felt was newsworthy.

“I can’t believe it today, but back in those days I had the prime minister or the head of the Security Service of Ukraine coming to me for an interview, not the other way around,” said Yakunov, who now works at the Ukrinform news agency. “Back then, reporters were very influential.”

In the 1990s, he was in charge of 150 journalists and a network of reporters across different parts of Ukraine who came to Kyiv every two months to pitch stories and pick up their salary.

Yakunov remembers Petro Shevchenko as one of his best journalists of the time.

Shevchenko was based in Luhansk, an industrial city of 400,000 resident some 800 kilometers southeast of Kyiv. Both Yakunov and Mostova described Luhansk in the 1990s as a dark and depressing city controlled by gangs so powerful that local government was either afraid to fight them or even conspired with them.

Before his death, Shevchenko published a series of stories about a local gang that ran a business registered as a fake charity organization called Veterans of Afghanistan to avoid paying taxes.

“Under the veil of delivering humanitarian aid to the region, those guys were smuggling alcohol into Ukraine and selling it here. And Petro (Shevchenko) found out that a local lawmaker was giving cover to the scheme,” Yakunov said, though he refused to name the lawmaker because Shevchenko had not managed to prove his theory.

The Luhansk City Council, then-headed by Oleksiy Danylov, was fighting the scheme, which supposedly also had cover from the local police. After Shevchenko was found dead, Danylov also felt threatened, as he was one of the main sources for the journalist’s investigation, Yakunov said.

Today, Danylov serves as secretary of Ukraine’s Security and Defense Council. He did not respond to a request for comment.

“Petro had published a story after a story on that scheme, and I understood that he was getting into some serious trouble there (in Luhansk). I told him to be careful as we were all in Kyiv and he was alone there with nobody to protect him. He promised me that he will publish one more story and let the authorities deal with the rest,” Yakunov said.

The editor does not remember if the final story was ever published. At some point, Shevchenko came to Kyiv to pick up his paycheck.

“Our regional correspondents’ supervisor met him at the railway station and wanted to take him straight to the newsroom, but Petro said he needed to go someplace and will come in later,” Yakunov recalled.

After that, Shevchenko disappeared for three days. His colleagues reported his disappearance to the police. Four days later, on March 13, 1997, Yakunov got a call from one of his top crime reporters in the middle of the night.

“He told me Petro was found hanged in a boiler room in the area called Kadetsky Hay,” Yakunov said.

The police decided the journalist had died by suicide. They had even found a suicide note on the scene.

“The note read: ‘The KGB has been chasing me and they finally got me’,” Yakunov said. “We were puzzled. Was the suicide staged or was there someone who made Petro do it? Because if he was planning to kill himself, why did he come to Kyiv for that?”

Police and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) started an investigation and promised to find answers to those questions. Yakunov and other Kievskiye Vedomosti journalists transported Shevchenko’s body to Luhansk to his wife and son.

“Back then, we had a clear feeling that he was killed. And I felt guilty because I hadn’t persuaded him to drop the dangerous topic,” Yakunov recalled.

After the funeral, Yakunov and two other journalists tried to figure out who could have killed their colleague — gangsters or the SBU, formerly the KGB. For that, they wanted to organize an interview with the chief of the local SBU department in Luhansk. However, their request was denied.

“We needed to get the interview. So I decided to use the home phone number that Volodymyr Radchenko, the SBU chief, gave me once. We called him and asked him to persuade the local security service,” Yakunov said.

They got the interview in the middle of the night, just several hours after the call. Yakunov said that after the interview, law enforcement assured him they had nothing to do with Shevchenko’s death. Then-President Leonid Kuchma said he would take the investigation under his control. However, investigators came to the same conclusion: suicide.

“And they have never found out who made him do that,” Yakunov said.

The newspaper bought an apartment for Shevchenko’s wife and son. However, they soon left Ukraine. Despite that, Shevchenko’s friends and colleagues continued to demand a renewed investigation into his death. Their last call was published in 2014. However, the case had been sent to the archives long ago.

Not the only one

Shevchenko was just one of many journalists who died in unusual circumstances in the 1990s.

Vadym Boyko, a Ukrainian TV journalist and head of the freedom of speech committee in parliament, died in a fire at his apartment in 1992.

The investigation into his death was closed after two months. Police said the fire was caused when a television’s cathode ray tube exploded. Boyko’s friends told the press that, before his death, he was investigating military smuggling schemes and the embezzlement of former Communist Party funds. He was aware that he could possibly be attacked.

“I was at the crime scene that night and saw his burned body in the middle of the room. I had a feeling the killers set his apartment on fire after they murdered Vadym. His neighbors saw the front doors on fire. The forensic test later showed that Boyko died before the fire. There was no ash in his lungs. He was just 29,” Dmytro Ponamarchuk, the president of the Viacheslav Chornovil Free Journalists Foundation wrote in an opinion piece for the glavcom.ua news website in 2017.

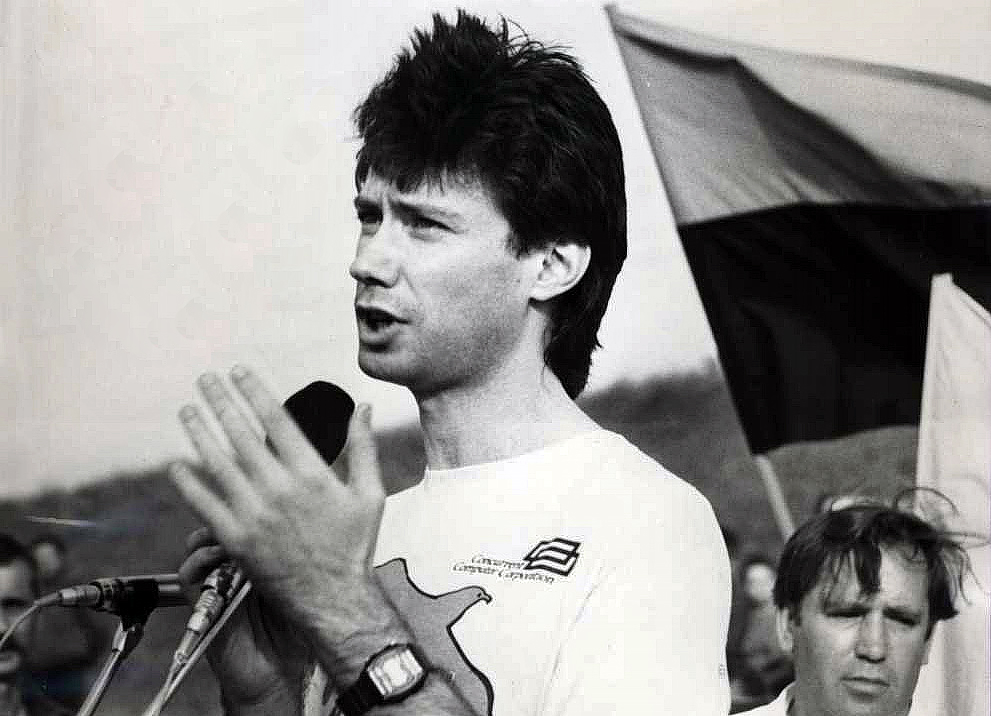

Journalist and member of parliament Vadym Boyko speaks during a meeting in Kyiv. Boyko died in a fire in 1992. He was one of the first journalists who died in unusual circumstances in 1990s Ukraine.

Viktor Frelikh, another prominent freelance journalist and environmental activist from Chernivtsi, died from poisoning with an unknown chemical substance in 1995. Before his death, he was investigating a strange 1988 alopecia outbreak in Chernivtsi Oblast, in which more than 175 children lost their hair, the Ukrainian-U.S. newspaper Svoboda reported in 1995. Other media reported that more than 300 kids suffered from symptoms of chemical poisoning at the same time.

The Soviet Union conducted an investigation and concluded that the children suffered from thallium food poisoning. However, many years later, Viktor Bachynskiy, an epidemiologist involved in the local commission investigating the case, said that his laboratory found hydrazine, one of the chemical elements used in rocket fuel, in the urine of some of the affected children, the inform.cv.ua news website reported.

His conclusions were never taken into account by the commission from Moscow, and the results of the investigation were soon classified.

Frelikh, who decided to investigate the situation after the USSR collapsed, was confident that the military was to blame for the outbreak. He reported that a leak of rocket fuel or another chemical substance occurred at a Soviet Army base near Chernivtsi Oblast. Several months before his death, Frelikh complained that he was receiving threatening phone calls.

In 2015, Frelikh was honored by the Newseum in Washington D. C. and included in a list of journalists killed in Ukraine for their work.

“Journalists were very influential in the 1990s. Some really powerful people were afraid of us, others sometimes seek our protection,” Yakunov said. Unfortunately, that did not protect journalists from attacks. Yakunov recalled that, at the time, he was receiving threats from gangs in Kyiv after his newspaper published stories about their gatherings.

“A gang’s representative could just come and warn you that next time they would kill you or your family,” Yakunov recalled.

Mostova said she had to deal with another type of criminal: those in the government. After the first years of freedom, in 1994 state officials started closing newspapers, confiscating print runs, raiding publishing houses and much more to force journalists to keep quiet. But that did not stop them.

“Of course you had to maneuver to survive in the 1990s. But being a fair journalist, devoted to the profession and not choosing sides was the minimal guarantee of your safety. Minimal because those were unpredictable times,” Yakunov said.

Journalists killed or who died under unusual circumstances in the 1990s

Myron Liakhovich, a journalist from Lviv, killed in December 1992. Chief editor of the “Zhyzn I Trud” newspaper. Died from an explosion.

Valeriy Glezdenyov, military correspondent of the Krasnaya Zvezda newspaper, died in 1992. Killed during the civil war in Afghanistan.

Vadym Boyko, died on Feb. 14, 1992. A TV journalist and a lawmaker who led the freedom of speech committee in the Ukrainian parliament. He died in a fire at his apartment. The investigation of his death was closed after two months. Police said it was an accidental blast of a TV cathode ray tube, causing a fire that killed the journalist.

Sviatoslav Sosnovskiy, editor of Tavriya publishing house in Crimea, died on May 23, 1993 after a group of bandits attacked him with knives. Police qualified it as hooliganism.

Mykola Baklanov, special correspondent of the Russian Izvestiya newspaper in Kyiv, died on July 22, 1993 in a street attack.

Yuriy Osmanov, editor of the Areket newspaper, a leader of the National Crimean Tatars movement, died on Nov. 7, 1993. Found dead on a street in Simferopol. Police reported it was hooliganism, assault. But his relatives were confident it was a political assassination.

Sergey Shepelev, an editor of Vechirnya Vinnytsya newspaper, died on Jan. 1, 1994 in a fire at his apartment in Vinnytsya. He was reportedly tied to his bed before the fire started.

Anatoliy Taran, an editor at Obolon newspaper, died in March 1995. Found dead in Kyiv.

Volodymyr Ivanov, a journalist from Sevastopol. Killed by an explosive device hidden in a trash bin in a parking lot next to his house on April 19, 1995. He was chief editor of the Slava Sevastopolya daily newspaper. Local police said he was a member of the local mafia. To this day, the circumstances of his death remain unknown and the murder remains uninvestigated.

Viktor Frelikh, a freelance journalist, died on May 24, 1995. He was investigating strange chemical pollution near Chernivtsi Oblast that affected many people in the region in 1988. Reportedly poisoned by an unknown chemical substance.

Ihor Grushetskiy, a correspondent at the Ukraina-Tsentr newspaper, found dead on May 10, 1996. The Cherkasy journalist died of severe wounds to the head. Shortly before his assassination, he reportedly told fellow journalists that he was a key witness in criminal proceedings that involved the relative of an influential Cherkasy police official.

Oleksandr Motrenko, a TV journalist, died in Simferopol on June 22, 1996. He reportedly died after a police officer hit him in the head publicly near his office.

Volodymyr Bekhter, chief editor of the state broadcasting company in Odesa, died on Feb. 22, 1997. He was reportedly beaten to death by police officers.

Petro Shevchenko, special correspondent of the Kievskiye Vedomosti newspaper in Luhansk, died on March 13, 1997. A month before his death, he published a series of stories on conflicts between the local authorities and criminal gangs.

Vitaly Kotsiuk, a journalist at the newspaper Day, died in Kyiv on July 4, 1997. In the hospital, he said that on June 24 a group of men approached him on his way home via urban rail, robbed him, forced him to walk out of the Boyarka station and then set him on fire afterward. Police reported that he died because he received an electric shock from the wet railways.

Borys Derevianko, chief editor of the Vechernyaya Odessa newspaper, was shot dead on Aug. 11, 1997. Derevianko was an investigative journalist and critic of Odessa mayor Eduard Gurvits. He was shot by an assassin next to his house on his way to work. His assassin, Oleksandr Glek, was sentenced to a life in prison but was found hanged in his prison cell.

Mariana Chorna, STB TV news service channel editor and journalist. Found hanged in her rented apartment on June 24, 1999. Police qualified her death as a suicide, but colleagues said before her death she was getting phone threats from politicians who were supposedly trying to lure her into political PR.