This investigation is part of the JFJ Investigative Grant Programme and has been originally published by The Cable – Nigeria’s independent online newspaper. This is the second part of a four-part series investigation. The first part is available here.

This investigation takes a deep dive into the unresolved killing of three Nigerian journalists while on assignments between 2019 and 2020. For six months, Nigerian investigative journalist, Patrick Egwu, looked into these murders, those behind them, and the growing calls for justice by families of victims and press freedom groups.

In January 2020, hundreds of protesters from the Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN), a Shia Muslim group, had been swarming around Abuja, Nigeria’s capital city. They were protesting and demanding the release of their spiritual leader, Ibrahim El-Zakzaky, who has been in detention since December 2015.

Previous protests by the group had turned violent, with security forces firing live bullets at the protesters. About 40 members of the group have reportedly been killed, with civil society and human rights groups such as Amnesty International highlighting rights abuses during protests and calling on authorities to release those arrested.

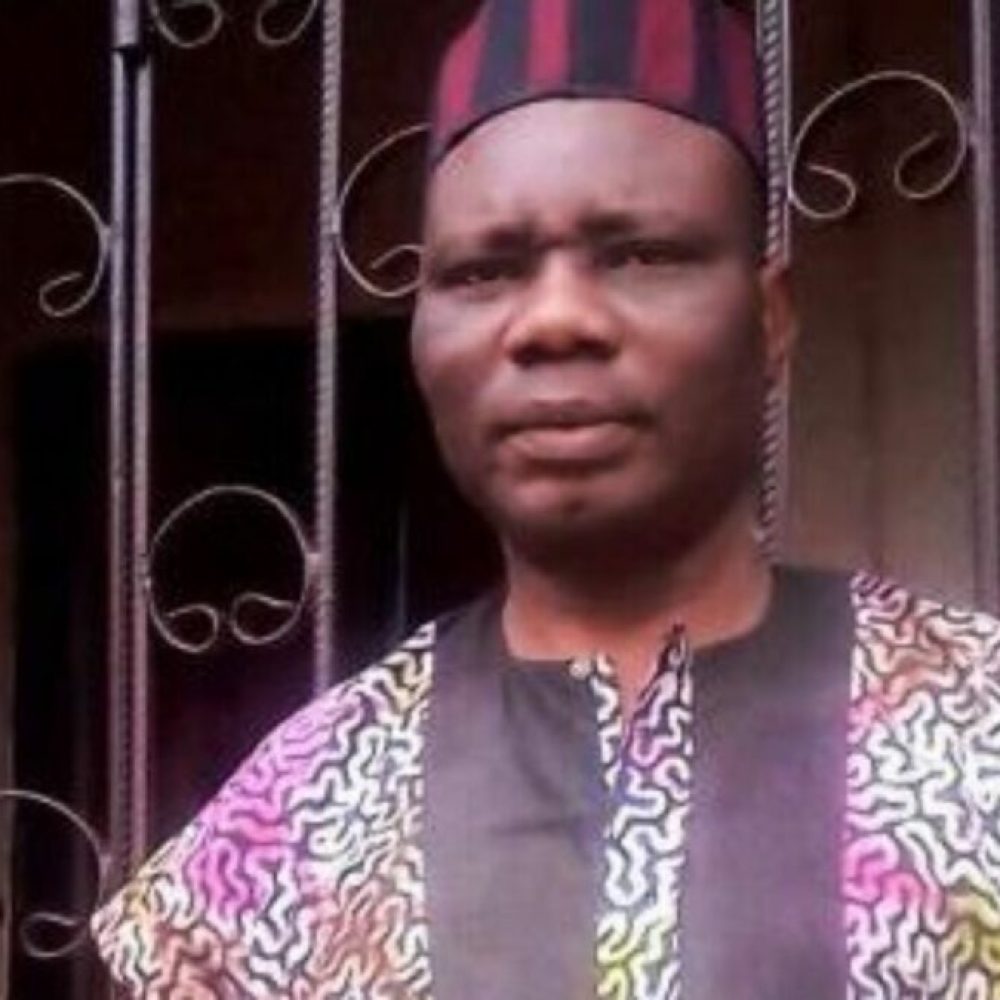

On January 21, Alex Ogbu, a freelance journalist, was at a bus stop waiting to taxi home when he saw the protesting group and felt it was an important story to tell. He moved closer to the scene to cover the protest when he was shot and killed by security forces who arrived at the scene and started shooting sporadically to disperse the protestors.

Anthony Osaigbovo, the investigative police officer in charge of Ogbu’s case, said he fell and struck his head on the ground which caused his death. But eyewitnesses at the scene said he was shot in the head by the police.

Ogbu, 50, left behind his wife and a two-year-old daughter whom he had told to “be a good girl at school” while leaving home that day, according to Francisca, his wife.

At 4:45 pm, shortly after he was killed, a police officer called Francisca on the phone and asked her to come to the police station.

“There is a little problem,” the caller on the other end told her. But when she got to the station in Utako, an urban district in Abuja, she received another call from one of her relatives who informed her that Ogbu had been killed during a protest. The police officer had been calling random numbers on Ogbu’s phone to inform them of his passing.

“He was my best friend, a very intelligent person and loves to make people happy,” said Francisca, who saw him for the last time when a friend came to pick him up in the morning. “He left for work like every other day and that was it.”

When he got the news, Sola Timothy Akingboye, Ogbu’s former employer and publisher of Regent Africa Times, informed the local journalism union and the human rights commission so they could take action.

“As a journalist, all of us are exposed to danger,” he said. “What happened to him (Ogbu) could happen to anybody and we need to rise up to the challenge.”

Attacks on journalists and media workers are common in Nigeria but have increased since 2015 after President Muhammadu Buhari’s election, just like his predecessor. A new report by the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA) and the Nigerian Union of Journalists (NUJ) shows that seven journalists have been killed by security forces including 300 violations affecting about 500 journalists in Nigeria during the current administration of Buhari, whose regime jailed and tortured journalists as a military ruler in 1984.

“I think we are experiencing this because, in a way, it looks like we are still in a military rule,” said Lanre Arogundade, the executive director of the International Press Council(IPC), press freedom nonprofit that fights for the rights and safety of journalists in Nigeria. “The military mentality still plays out in the way they conduct their affairs. So, when you talk of demilitarisation, you begin to wonder if the government and security agencies have been demilitarised in the sense that they understand that we are in a democracy where they have to follow the constitution and where the rule of law has to prevail.”

DENIALS AND LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE

Ogbu’s family is still seeking justice more than a year after he was killed. The police still maintain their first version of the story; that he died after he fell on the ground at the protest scene. At the National Hospital Abuja, Nigeria’s capital city, where his body was kept in the morgue, the police had told the mortician and other staff that Ogbu was an accident victim, and booked his body in, according to Francisca.

However, Francisca saw something different during her first visit to the morgue which corroborates the eyewitness report. “The police said he fell and died but when I saw my husband’s corpse, I saw the bullet wound and how it pierced his head,” she said.

A few days later after her visit to the morgue, the police asked Francisca to come to the station and write a statement and sign a consent document accepting their own version of the story in connection with his death.

“I called my relatives immediately and they told me not to sign anything,” she said, insisting on a private autopsy. “I decided l will do it because I wanted to fight for justice for my husband. One of the fundamental human rights is the right to life which had been taken from him. I told them I was determined to get justice.”

Francisca said an autopsy by the police which she closely monitored later confirmed that Ogbu died of gunshot injuries. But the police refused to give her the result and said: “It was the property of the Nigerian police.”

“We have bullet and gun numbers and certain guns were released on that day for that operation,” said Marshall Abubakar, a lawyer who is offering pro bono services to Ogbu’s family.

“This means that a particular bullet was assigned to a particular police officer but up to this moment, we don’t know who the said bullet was assigned to or who the policeman that shot him that day is.”

“The police authorities have proven to be what they are,” he added. “They have refused to disclose the identity of the officer that committed the murder. It is quite unfortunate but we will not relent in our demand for justice.”

In July 2020, one month after Ogbu was killed, Abubakar filed charges against the police and the state attorney on behalf of Ogbu’s family and has appeared five times in court to seek justice for the killing. But court proceedings have been stalled by strike action of judicial workers who were demanding better welfare packages — and currently, Peter Affen, the presiding judge sitting over the case, has been nominated for an appointment at the apex court in the country. A replacement is yet to be named.

“It’s still complicated,” Francisca said, referring to the court proceedings. She added that she wrote a petition to the judicial panel set up by the government last year to investigate cases of police brutality across the country.

“I was invited and they said I needed to withdraw the matter from the court if I want them to hear the case,” she said, referring to the judicial panel. “I told them I was hoping that the justice I would get from the panel will be evidence I will use to support my case but they said it doesn’t work like that.”

Francisca says she remains determined to get justice and insists she doesn’t want compensation after the police authorities approached her for an out-of-court settlement.

“I want the police to admit that they killed my partner,” she adds.

After the funeral of Ogbu in January last year, Francisca said she had to take the painful decision to tell her two-year-old daughter that her father, whom she slept close to and woke up each morning to see, had died and won’t be returning home to her anymore.

“She has an idea of what is going on now,” she says. “Sometimes she wakes up at night and cries for her daddy because she usually slept close to him when he was alive. So, she knew something was wrong.”

From where she is seated in front of the apartment she once shared with Ogbu, Francisca said she won’t give up on anything. “It’s just sad but I will see to the end of the matter,” she said. “I also want to be strong for my daughter.”