This investigation is part of the JFJ Investigative Grant Programme and has been originally published by The Cable – Nigeria’s independent online newspaper. This is the last part of a four-part series investigation. The first part can be found here, while the second part is available here. The third part can be found here.

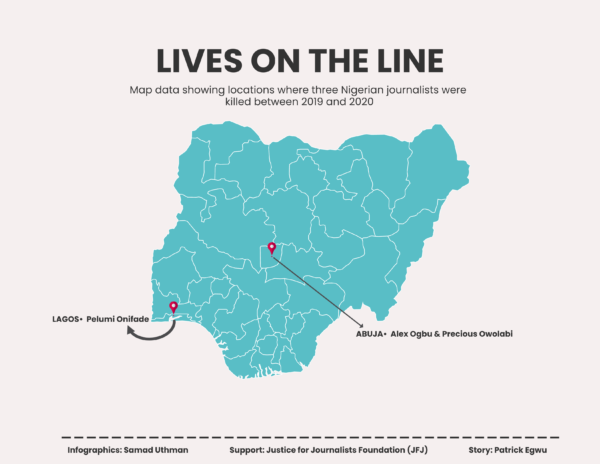

This investigation takes a deep dive into the unresolved killing of three Nigerian journalists while on assignments between 2019 and 2020. For six months, Nigerian investigative journalist, Patrick Egwu, looked into these murders, those behind them, and the growing calls for justice by families of victims and press freedom groups.

Pelumi Onifade, Alex Ogbu and Precious Owolabi died while on different assignments in less than two years. This is the highest number of deaths of journalists recorded in modern Nigerian media history in a short span of time since the killing of two Nigerian journalists covering the Liberian civil war by rebels loyal to Charles Taylor in 1990.

In many ways, the perpetrators of these attacks have been emboldened by the hierarchy that shields them and the lack of accountability. There has never been closure or justice for families of more than a dozen journalists killed in Nigeria by agents of the state while on assignment. No one has been arrested, prosecuted or convicted for the killing of a journalist in Nigeria.

“There are instances where the journalists would receive an apology but those responsible for attacking journalists, detaining them and harassing them are not held accountable, so there are no consequences for those that perpetuate these abuses,” said Jonathan Rozen of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

Lanre Arogundade, who works with other nonprofits to protect journalists, said this happens “because we don’t have the culture of accountability in the country. The police always promise to do something but nothing comes out of it”.

On October 19, 1986, Nigeria’s foremost investigative journalist, Dele Giwa, was assassinated through a parcel bomb. This has become the first known murder of a journalist in the country. The military government at that time, which was famous for human rights abuses, was blamed for the killing. More than 35 years later, no one has been arrested or prosecuted in connection with the killing despite different panels of inquiry and commissions set up by successive governments to investigate the murder and hold those responsible accountable.

Chido Onumah, the coordinator of Nigeria-based African Centre for Media and Information(AFRICMIL) said lack of accountability is the nature of the government and the state.

“It just tells you that the impunity reigns supreme here,” he said. “It seems to be the directive principle of state policy. Protesters are shot at by security forces and they lack the capacity to investigate the killings or establish those who committed the murder.”

Onumah added that the state institutions are weak and “that is why people get away with murder here because the state is so ineffective and unable to hold people accountable for crimes committed”.

“It almost feels like the lives of citizens here do not matter in this country. The attacks and the fact that they have been unable to resolve the murder cases involving journalists is just an extension of general lack of ability to investigate these cases and the general impunity here,” he said.

Protection and safety training

Lekan Otufodunrin, a media mentor who has worked with and trained dozens of Nigerian journalists, says safety training and simulations are very important for journalists to cope while on dangerous assignments like protests, conflicts, war zones, and violent demonstrations.

“When these kinds of incidents happen, it creates fear and people begin to worry about their safety,” he said. “This is why media organisations need to prioritise the safety of their staff.”

Otufodunrin says precaution is also necessary for newsrooms when dangerous assignments are assigned to journalists. “When they are on assignment like this, they need to ensure that the journalists are safe. It is not enough to tell journalists to go and cover events but to take steps to make sure they are safe and prepare them for possible dangers ahead.”

Arogundade adds that there should be greater commitment and investment on the safety of journalists, especially on the part of individual media organisations.

“I cannot say if they (media organisations) are doing much in providing enough security training for journalists,” he said. “They do not provide adequate protection to journalists when they go to cover such assignments. Security agents don’t also see it as part of their duties to protect journalists.”

In Nigeria, journalists work under extremely difficult situations. Apart from poor welfare issues, they operate in an atmosphere where they are regularly attacked, and arrested by agents of the state, with some of them going on exile. Most of them who cover dangerous assignments have no insurance cover but have to take risks and put their lives on the line to tell important stories.

“I think journalists have to live with very difficult circumstances because when they go out in the field, there are many risks associated with that,” Rozen said. “And what we do at CPJ is that we are providing journalists with the information and resources which ideally and hopefully will help them to stay safe in those situations while doing their jobs.”

As a nonprofit, the CPJ provides journalists everywhere around the world with safety information, digital security and protection, and physical safety for covering different situations including civil unrest.

Rozen said another issue that goes under-appreciated is the psychological safety of journalists. “If you are covering civil disorder or clashes of some kind, that is a stressful environment to be in the middle of and journalists are often in the middle of those situations, trying to get as close to the story as possible and in doing so, they need to remember and be conscious of the fact that that can have an effect on their mental health.”

In cases like this, Rozen says the CPJ comes in to provide resources and tips on mental health, psychological safety and specific advisories from experts to help journalists.

“We will continue to push for the safety of journalists in Nigeria to improve and for those responsible for the safety of the public [police] to prioritise and ensure the safety of journalists while they carry out their job.”