This investigation is part of the JFJ Investigative Grant Programme and has been originally published on The NewsHawks website. This special report was also published in the 50-page PDF edition of The NewsHawks newspaper on 19 November 2021.

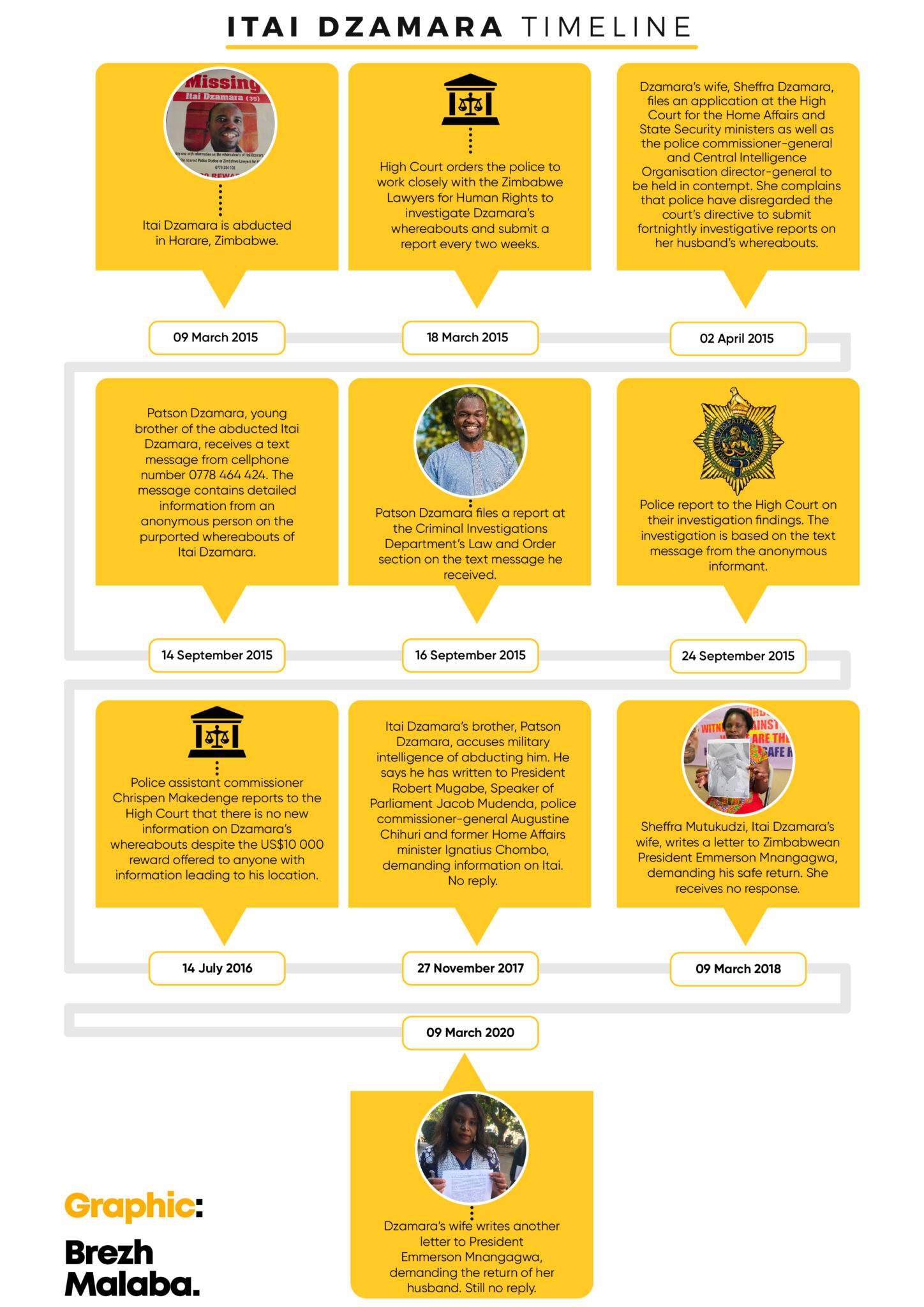

On 9 March 2015, Dzamara was dragged out of a barber shop in Harare’s Glen View 7 high-density suburb by five men in plain clothes, handcuffed and bundled into a white truck.

He has never been found. Six years on, his abduction, in broad daylight and in a busy urban area, remains a frightening mystery in a country described by Amnesty International as one of the most hostile environments for journalists and human rights defenders in Africa.

Before his abduction, Dzamara had repeatedly been beaten up and harassed by state agents for demanding the resignation of long-time authoritarian ruler Robert Mugabe, who had been in power for 35 years. After founding the Occupy Africa Unity Square movement, he was often seen in Africa Unity Square in central Harare, wielding placards in solo protest. Stunned onlookers would shake their heads in disbelief, amazed by his courage in confronting a regime notorious for torture and mass murder.

The Dzamara case is important because as long as Zimbabwe’s ruling elites continue intimidating, abducting and torturing journalists and human rights defenders without repercussion, the impunity can only worsen. It also brings into question the commitment to democracy and human rights by President Emmerson Manngagwa’s government, four years after the dramatic ouster of long-time ruler Robert Mugabe.

Zimbabwe adopted a new national constitution in 2013. The supreme charter was supposed to usher in a new era of good governance, democracy and civil liberties.

Professor Jonathan Moyo, who was minister of Information when Dzamara was made to disappear, said the 9 March 2015 abduction and the military coup of 15 November 2017 which toppled long-time president Robert Mugabe are so far “the worst blights on the 2013 constitution”.

Moyo is now exiled, having fled the country under a hail of bullets during the coup. He has concluded that these two events — Dzamara’s 2015 abduction and the 2017 military coup — are “reminiscent of the hideous evils” of Mugabe’s authoritarian “First Republic” era. The “Second Republic”, under the leadership of President Emmerson Mnangagwa, who rose to power on the back of the coup, has been lamented by human rights campaigners as a continuation of Mugabe’s murderous rule.

On 9 March 2021, on the sixth anniversary of the abduction, the United States embassy in Harare tweeted: “Today marks 6 years since Itai #Dzamara’s forced disappearance. We continue to call on the GOZ [government of Zimbabwe] to investigate his abduction fully & to bring to account those responsible. We stand with his family and all Zimbabweans who exercise their freedoms of expression and peaceful assembly.”

Exactly 16 minutes after the US embassy tweet, President Mnangagwa’s spokesperson, George Charamba, replied on the same social media platform: “They (the Americans) really look after their poodles!” Those few words summarise the Zimbabwean authorities’ attitude towards Dzamara’s enforced disappearance.

Remarkably, conclusive information on Dzamara’s fate remains elusive, despite the offer of a US$10 000 reward — quite a fortune in an impoverished economy, whose average monthly salary barely exceeds US$120.

Award-winning journalist Hopewell Chin’ono, who has been repeatedly arrested by the authorities for his work, said the unsolved Dzamara case “brings dejection to journalism as a profession”.

“One of you can just be taken, just like that, and be made to disappear and it ends like that. This is a young man who left a family, he left a wife and two kids. There are economic issues around that; who’s going to take his kids to school? He also lost his brother who was an activist, so it’s a tragic story. For me as a Zimbabwean, the most tragic thing about Itai’s story is that citizens have just moved on like nothing has happened. Until citizens use their agency to put pressure on the state when something like this happens, the state will continuously do it because there are no repercussions, there’s no consequence for doing so.”

Abducted — 9 March 2015

The point of departure for our news crew was a blue makeshift cabin with a corrugated iron roof in Harare’s Glen View 7 high-density suburb. Deketeke Barber Shop has been in existence for 13 years, a remarkable feat for an informal business in a city where such tuckshops are routinely demolished by ruthless police and the municipal authorities.

Dzamara, the outspoken journalist and government critic, was abducted at this very barber shop on Monday 9 March 2015. He had come for a haircut. The barber who witnessed the shocking spectacle when five men stormed the shop and falsely accused Dzamara of stealing cattle before bundling him into a double-cab truck and speeding off is no longer working at the shop.

Our news crew entered the shop on a hot Saturday afternoon and found two young barbers. A haircut would cost US$1, they told our three-member crew. Two of us sat down and requested haircuts. It was a surreal experience—receiving a haircut in the same shop where Dzamara was snatched six years ago, never to be seen again. Sitting in that makeshift cabin, it was difficult to avoid the inescapable truth: that what happened to Dzamara can happen to anyone. He is a journalist, a human rights activist, a social justice advocate, a father, a husband, a brother and a Zimbabwean. If his enforced disappearance does not matter at all, then it means the life of every citizen is worthless.

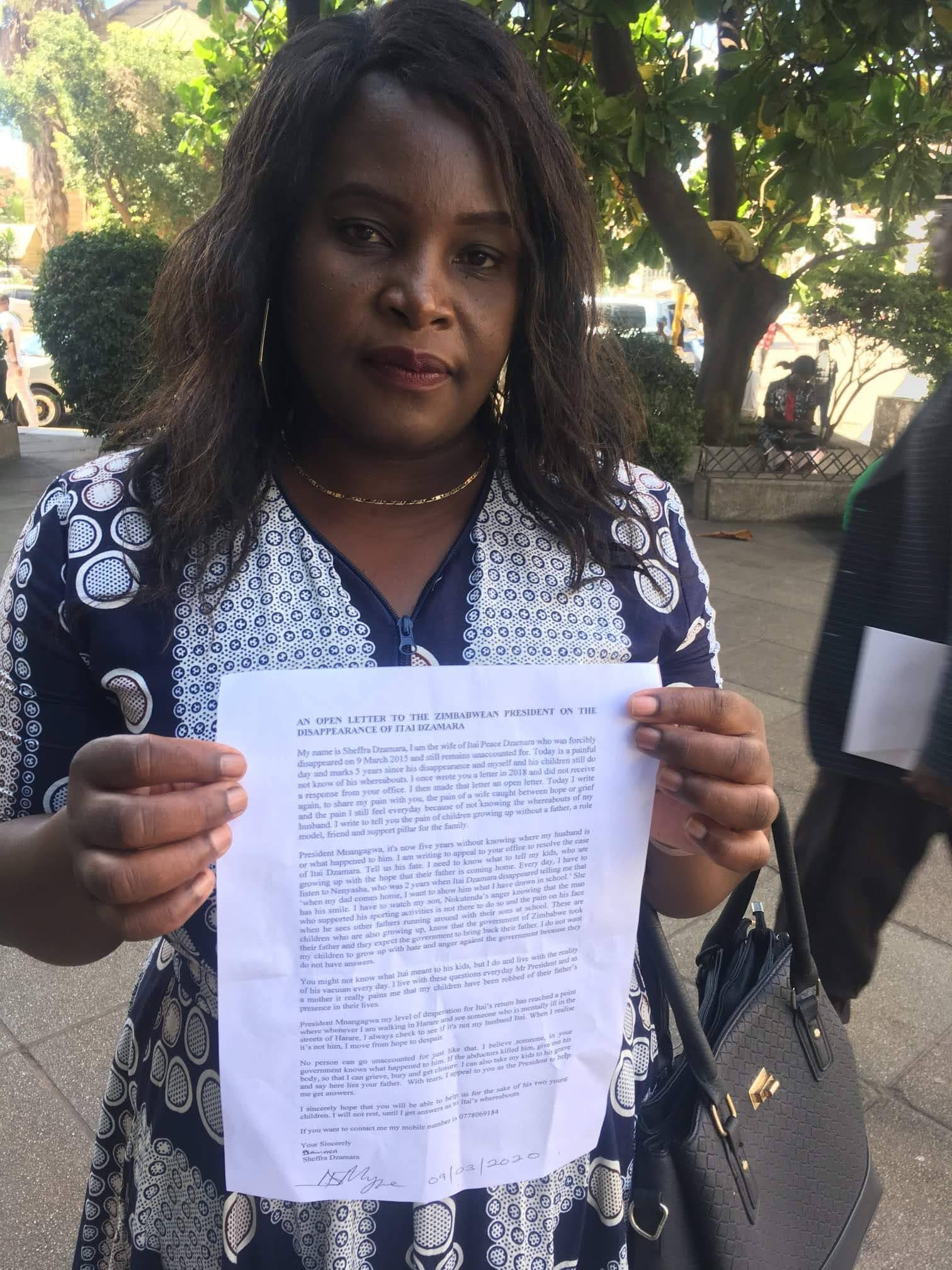

Anyone who seeks to fully understand the Dzamara case must speak to his wife, Sheffra Mutukudzi. However, it was not easy for our news crew to be granted an interview. For weeks, we had reached out to her, with the hope of establishing contact and building much-needed trust. Her first response was brusque and dismissive.

“These days I’m not interested in interviews.” With that short sentence, she could have easily stopped us dead in our tracks and torpedoed any attempt to dig deeper into an enforced disappearance which has come to symbolise Zimbabwe’s tragic record of state-sanctioned human rights violations.

After weeks of cajoling, she relented. In mid-September, with Harare’s tree-lined roads transforming into a riot of colour as the majestic Jacaranda trees began blooming in all their glory, Mutukudzi finally opened up to our news crew. “I will grant you an interview.”

On a sweltering afternoon, we met Mutukudzi outside a shopping mall in central Harare. The streets were bustling with cars and pedestrians. Nothing unusual. But it became apparent she would not feel comfortable sitting in a public space and discussing the horrors her family has been subjected to. Zimbabwe’s traumatised society has been governed by fear for four decades.

There is a terrifying belief that spies are everywhere. We had to think fast. The solution was simple enough: we would interview her while driving leisurely around the central business district. She agreed and, thanks to the relative privacy of darkly tinted car windows, began narrating her heart-rending story.

“I’m tired of granting interviews to people who only remember us during the anniversary of my husband’s abduction. We have been reduced to a forgotten thought. If we’re lucky, people remember us once a year, but for the rest of the time we don’t exist. It’s as if everyone forgets that Itai has children and a family,” she said calmly. Dzamara’s son Nokutenda is 13 years old this year and daughter Nenyasha is nine. They were aged seven and three respectively when their father was abducted.

The children deserve a bright future, she emphasised. “At times people ask me whether I’ve been getting money from organisations following my husband’s abduction. I don’t get a cent. I must ensure that these children don’t suffer in future.”

After we navigated through Harare’s labyrinth of busy one-way streets, our first interview with Dzamara’s wife came to an end. She asked to be dropped off near a commuter omnibus pick-up point. Two days later, we had our second interview.

After picking her up in central Harare, we drove to a multi-media studio. Her countenance appeared more relaxed this time around, until she dropped a bombshell: she was uncomfortable with a video interview, for security reasons. She eventually agreed to meet us halfway: the video interview would go ahead, but she would not take off her face mask.

Mutukudzi said her husband’s enforced disappearance turned life upside-down for the family. She is convinced he was abducted by the state. All the objective facts pointed to that: the constant surveillance he was subjected to; the brutal assaults at the hands of police; the make-believe official investigation into his disappearance; the refusal to reveal Dzamara’s fate, even after president Robert Mugabe was toppled in the 2017 military coup.

Every year, Mutukudzi writes a letter to President Emmerson Mnangagwa, asking him to provide answers on the fate of her husband. He has never replied. “When he came to power, our family thought Mnangagwa would help us with information on my husband’s whereabouts. He has not bothered to reply to my letters,” Mutukudzi said.

Charles Kwaramba — Dzamara’s lawyer

Charles Kwaramba (pictured above) was admitted to practice law in Zimbabwe in 2004. He has been a partner at Harare law firm Mbidzo, Muchadehama and Makoni Legal Practitioners since 2008. In 2011, the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights recognised his work ethic and bestowed on him the Lawyer of The Year accolade. We interviewed him at his suburban office in Belvedere.

“I have no doubt that he (Dzamara) was taken by the state. It’s my conclusion. I arrived at this conclusion after looking at the cumulative facts.”

“It’s so difficult to absolve the state. What other enemies would Dzamara have had who would have wanted to kill him? He was in a daily fight with the state, so the first suspect is the state. Whenever a person disappears, one of the first questions you can ask is: Who would have harboured any ill intention against this person? It’s actually a lead and it entails finding the persons who would have had a recent spat with the person who has disappeared or died. In fact, no one else could have abducted Dzamara; he was under the constant surveillance of the state. If any third party tried to harm him, the state would have known because they were always monitoring his movements.”

“It was not a robbery. Why would anyone abduct a person who is in a barbershop? He probably had just enough money for a haircut.”

Dzamara’s lawyers successfully applied for a High Court order directing the police to submit investigative reports, every two weeks, on the enforced disappearance.

‘Suspicious’ vehicle

On Thursday 5 March 2015, four days before Dzamara was abducted, his wife Sheffra spotted a vehicle she described as “suspicious”, which had parked outside their home in Harare’s Glen View 7 suburb. She submitted the registration number, AAM 1732, to the police. Astonishingly, the police did not follow up on this lead.

“Up to this day they have not disclosed to me what investigations they did regarding the status of that car. All they have done is to keep asking me to attend at the police station to give a statement. I am now really tired of giving these statements which have not borne any fruit,” said Sheffra.

Dzamara’s lawyer, Kwaramba, said the failure by police to investigate the vehicle feeds into the suspicion that the authorities are not serious about investigating the case.

“This would have been a special lead, to establish the owner of the car. And had they investigated, they could have found out who was driving the vehicle on that day and so forth,” Kwaramba said.

“We were not raising this allegation recklessly; we actually stated it in our affidavit to the court when we filed an application for contempt of court. Our complaint was that police were not investigating this matter. They were doing nothing. We told the court that there is this lead which they have not followed up. But still, even after we filed that application raising that allegation in the affidavit, there is still no report as to what the police did in respect to that allegation.”

“For us, that was an omission which was disturbing and very strange.”

An investigation by The NewsHawks has established that the vehicle in question is a silver Mazda B2500 double cab. We can reveal that the AAM 1732 number plate has since been replaced with plate number ACB 0810. The truck is registered under the name of one Nzwiraingoni Moyo of Redcliff. Moyo, a chemist by profession, was a technical manager at Redcliff-based chemical manufacturer Zimchem until 2017. It was his allocated company vehicle.

Our news crew traced Moyo, who said he stopped working for Zimchem in 2017 and is now self-employed. He said the Mazda double cab truck now belongs to him and ownership was changed to his name as part of an executive package. In 2015 — the year of Dzamara’s abduction — he was using the vehicle. But he denied ever driving to Harare’s Glen View suburb, where Dzamara was snatched by unknown men.

“I never drove to Glen View. I remember going to Budiriro some time back, not Glen View,” said Moyo. The police have never explained why they never found it necessary to follow up on this lead, despite being given the vehicle registration number by Dzamara’s wife.

The NewsHawks sent questions to the Zimbabwe Republic Police but they had not responded at the time of going to press, even after promising to do so.

Anonymous informant

Itai Dzamara’s brother, Patson Dzamara — who is now deceased — was contacted by an anonymous informant who said he had information on the missing journalist. He directed Patson to go and park outside the five-star Meikles Hotel in central Harare. Patson did as told.

As Patson waited in the hotel’s external parking lot, which is on the street in front of the main entrance, a man came to his car and claimed he was from military intelligence. The man gave Patson a picture purportedly depicting a blindfolded Itai in captivity. Patson went public with this picture, posting it on social media. Kwaramba says when Patson publicised the picture, the police summoned both Patson and himself to come and explain what they were trying to achieve.

“Police said they were concerned with Patson’s decision to go public with that picture, saying it was quite a sensitive issue. The police then called us (Patson and the lawyer) and we went to them. They told us not to publicise these things before coming to them first so that they could conduct verifications because they said this was a sensitive matter.”

Kwaramba said this was a red flag. The actions of the police suggested that “they were more concerned with bad publicity than following up on anything”.

The cellphone number used by the anonymous informant to send text messages to Patson is 0778464424. The line is registered in the name of Hope Mubaiwa of Palm Court in Redcliff. Mubaiwa, a Form Three student in 2015, said she bought the cellphone line from a street vendor in Kwekwe. She said the line was rejecting airtime recharge, resulting in her disposing it at Palm Court. She denied any knowledge of Dzamara.

Another difficult lead

As far as the police were concerned, Patson’s encounter with the anonymous informant did not appear to yield actionable intelligence.

For starters, the man who claimed to be a member of the military was unknown to Patson, meaning his identity would remain shrouded in mystery. Patson claimed when he visited the United States he submitted the picture for forensic analysis.

Kwaramba, the lawyer, explained: “Patson told me the picture was analysed by forensic analysts and that they confirmed that the picture of a blindfolded Itai was indeed authentic. However, Patson did not furnish me with written findings of the forensic analysts, so even for us as lawyers we couldn’t take it up.”

The mystery surrounding the informant’s picture of a blindfolded Dzamara is far from over.

His wife, Sheffra, is convinced the picture is genuine. “That is definitely my husband. It’s him. I have no doubt. I know him, even with my eyes closed. He had a damaged toenail on one foot, and when I look at that picture, I can see the damaged toenail. A fake photo would not have that damaged toenail. That’s Itai,” Sheffra said.

Patson’s death

In the aftermath of Itai’s abduction, Patson became very vocal in demanding justice. On 18 April 2016, Patson caught Robert Mugabe’s bodyguards by surprise. In the National Sports Stadium, as the strongman delivered a keynote address marking Zimbabwe’s 36th anniversary of independence, Patson — draped in the national flag — stood in front of Mugabe and displayed a placard demanding the return of his brother. He was arrested and brutally assaulted by state security agents for his audacious one-man protest. It was just one of his countless encounters with state-sponsored violence.

On 18 November 2016, Patson was abducted by several armed men on his way to a meeting to organise an anti-corruption protest. They drove him to the Lake Chivero area, about 33 kilometres south-west of Harare. They tortured him, held a gun to his head and warned him: “You haven’t learnt and taken heed of how we treated your brother and now your time to learn is upon you.” They beat him up, stripped him naked and left him for dead. Around 3am, a passer-by helped him reach a petrol station. On 26 August 2020, Patson died of colon cancer. He was 34. Members of his family believe he was poisoned.

Speaking at his memorial service in Mutoko on 26 September 2021, outspoken cleric Ancellimo Magaya revealed that Patson was injected with what is suspected to be a harmful substance.

Patson himself, a few weeks before his death, told this writer that the unidentified men had injected him with an unknown substance.

In an interview, Bishop Magaya told our news crew that the Mugabe government, “whose system is still operational” under Mnangagwa’s administration, must be held fully responsible for Itai Dzamara’s enforced disappearance.

“It is very sad that he went missing in a context in which we had actually voted for a constitution that allows freedom of speech, freedom of association and freedom of expression. Itai Dzamara went missing because of his expression and his association. That is very sad, we really condemn that in the strongest of terms.”

“There were noises made, way back, regarding Itai Dzamara, but right now the voices are growing fewer and fewer. So we’re saying that we should never be quiet till justice happens. Wickedness of such levels should be condemned. We warn that it will not go unpunished. God, one day, will actually ensure justice is executed,” Bishop Magaya said.

Police reports dry up

Police stopped submitting their investigative reports on 14 July 2016. Curiously, the police have not formally told the High Court that the investigation has hit a dead end — if that indeed is what has happened. They just stopped reporting on the case.

“This investigation was much ado about nothing because the state was investigating itself. I feel we were taken on a wild goose chase. I didn’t feel that it was a serious investigation.

“The main contention for me was that the state was being asked to investigate itself. The state was the main suspect in the matter; our court papers said so.”

Kwaramba said the lack of seriousness shown by the authorities in probing the enforced disappearance is unsettling. “It’s horrible. The impact of the Dzamara case is serious. It sends shivers down the spine of anyone who practices human rights work. The realisation that I can just disappear.”

Dirk Frey — Dzamara’s comrade

Dirk Frey is a prominent activist in Zimbabwean civil society. He became one of the leaders of the Occupy Africa Unity Square, the protest movement founded by Dzamara.

He vividly recalls the days leading up to Dzamara’s abduction. The group was locked in cat-and-mouse skirmishes with the police. The law enforcement agents — both uniformed and in plain clothes — were determined to violently ensure that the protesters did not get an opportunity to exercise their constitutional rights to free expression, association, assembly and peaceful protest. Their protests were repeatedly scuttled by truncheon-wielding policemen. Many protesters, including Dzamara, were injured in these attacks.

Frey recounted to our news crew the frenetic activity in the days leading up to the abduction.

The outspoken journalist and activist was “under constant surveillance”.

Dzamara was abducted on Monday 9 March 2015. Two days earlier, on Saturday 7 March, he had addressed a rally of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) at the iconic Zimbabwe Grounds in Harare’s Highfield township. The venue is revered in Zimbabwe’s anti-colonial history. MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai’s choice of that arena for such a pro-democracy rally was pregnant with political symbolism.

“Surveillance always intensified whenever anything was going on, and he had just addressed an MDC rally at Highfield, so it was quite natural for the (state security) system to pile on the surveillance,” Frey says.

How Dzamara spooked Mugabe government

On 3 March 2015, Dzamara wrote excitedly on his Facebook page about the upcoming 7 March rally. He dubbed it the “Team New Zimbabwe Mega Rally!!”

“This Saturday, I will be at the Zimbabwe Grounds in Highfield, Harare, for a mega rally organised by the MDC-T but specifically for laying down the agenda of collaboration and collective engagement by stakeholders and players fighting for a new Zimbabwe. I am thrilled by this step, because I have been ardently yearning and calling upon MDC-T leader Morgan Tsvangirai to step up, walk the talk and work on the collaboration agenda,” Dzamara wrote.

The “collaboration agenda” which Dzamara was referring to was the growing call by opposition groups to close ranks and mount united opposition to Robert Mugabe’s repressive government amid worsening economic hardships. The context in which Dzamara and his colleagues were agitating for political change in Zimbabwe is crucial to understanding the zeitgeist of that material time. The opposition MDC had outpolled the ruling Zanu PF in the bloody 2008 general election, but Mugabe was clinging on to power and refusing to go. The opposition claimed the 2013 election was also stolen. The Arab Spring — a tumultuous series of anti-government protests — was sweeping across the Arab world including North Africa, toppling authoritarian regimes and providing inspiration to pro-democracy formations.

A retired operative of the Central Intelligence Organisation, the state security agency, told our news crew that Dzamara’s one-man protests were causing headaches for the security apparatus. His identity cannot be revealed.

“At first, he was seen by some in the (security) system as a harmless guy who would be ignored by the citizens and soon fizzle out. There are two factors which proved that assessment wrong. First, he was brave. How many people in those days could carry a placard in the middle of Harare and demand the resignation of Robert Mugabe? Mugabe was feared.

Second, he began galvanising opposition groups, urging the youth, in particular, to unite in demanding change. The Zimbabwe Grounds rally which was organised by the MDC was a turning point in the sense that some people in the security establishment began seeing him as more of a threat than a nuisance,” said the retired spy.

At the 7 March 2015 rally, Dzamara took to the stage and urged all pro-democracy groups to unite. His speech, in solidarity with the opposition MDC, marked a shift from his usual sporadic public protests to a clearly defined opposition pedestal.

On Tuesday 10 March 2015, the then MDC president Tsvangirai issued a statement holding the government accountable for Dzamara’s abduction the previous day.

We are in no doubt as to the perpetrators of this abduction. We hold Mugabe and his regime responsible for this morbid and senseless act,” said Tsvangirai who, from 2009 to 2013 had served as prime minister of Zimbabwe in a power-sharing government.

He added: “We hold the state culpable. We hold Zanu PF responsible. We demand a full investigation and arrests of the culprits so that Zimbabweans can live in the comfort that we have a government that cares and takes seriously its responsibility to protect citizens.”

Who took Dzamara?

We posed this question to one of his closest allies in the Occupy Africa Unity Square protest movement, Frey.

“Given the case remains unsolved, it is impossible to say with any certainty. The best we can do is an educated guess. We know from the eyewitnesses at the scene that a team of five men in plain clothes took him and handcuffed him. The bizarre accusation of cattle-rustling and the use of handcuffs combined with the prior surveillance makes it highly probable these men were part of the state security apparatus. Unfortunately, since the investigation into their identities met a stone wall, we cannot identify them positively,” Frey said.

“Everything from there is guesswork and the uncertainty whispers of the cloak-and-dagger world.”

Frey points out that the police never showed seriousness in investigating the abduction.

“It seems clear that they had no interest and in fact received clear instructions to obstruct any efforts to the point that a court order had to be obtained to force them to make a report.”

When we asked Frey who else, apart from the state security apparatus, had shown any determination — if at all — to harm Dzamara, he said he is not aware of anyone who would have harboured a sinister motive.

“All of this said, the regular, obvious and disproportionate violence meted out on him by the state makes this a moot point. Anyone that might conceivably want to see him harmed simply needed to stand back and let the state do it. There are no other lines of investigation and none are necessary or warranted,” Frey elaborated.

Will mystery ever be solved?

Frey is convinced the abduction was carried out by trained security personnel.

“There are most certainly people that know what happened to Itai Dzamara. Those who organised the abduction, ordered it and carried it out. An operation like that takes logistics, trained individuals, experience. This was not the first or the last time this sort of thing happened. The fact that information is scarce points to rigorous information control, operational security, hence trained and organised people. Which, once more, points back to the security apparatus of the state. Especially if the police are unwilling to investigate, which indicates structures with more clout than they.”

“To me, all the arrows point back to the state through its security apparatus protecting the perpetrators. Barring a dramatic development, the only certainty of getting answers is once those powerful individuals and structures are no longer in power and can be hunted down and arrested.”

Military Intelligence Directorate

Writing on Twitter on 14 July 2018, former Information minister Jonathan Moyo made a bold assertion that Dzamara was abducted by the Military Intelligence Directorate (MID). He re-tweeted this on 23 August 2019.

“The MID officer who oversaw this is Brigadier-General Mike Sango who was then CDI (Commander Defence Intelligence) and is now Zimbabwe’s Ambassador to Russia. Why did they do this? To build a case against President Mugabe, as they did on 7 March 2007 with their savage attack on Tsvangirai,” wrote Moyo.

Moyo’s claims are worth scrutinising. He was one of Mugabe’s most formidable political schemers.

In a series of tweets, Moyo says that in the aftermath of the controversial dismissal of Emmerson Mnangagwa as Vice-President on 6 November 2017 “a lot of credible informants came forward with tonnes of information implicating Mnangagwa and his cohorts in unspeakable atrocities. Really. This is a fact that not even an earthquake will ever destroy!”

Moyo adds: “I got to know from a high-level source with access to the information; that ZDF’s (Zimbabwe Defence Forces) Military Intelligence Department (MID) abducted Itai Dzamara & subjected him to extreme torture like in the Gukurahundi (1980s genocide) & State of Emergency days. Mnangagwa, Chiwenga & Mohadi know about this!”

The three men mentioned by Moyo in this particular tweet are: Mnangagwa, who was Acting President at the time Dzamara was abducted; Constantino Chiwenga, who was Commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces back then; and Kembo Mohadi, who was Home Affairs minister in charge of the police.

Moyo, a mercurial political scientist who played a key role in crafting the ruling Zanu PF’s election manifestos and key political strategy during Mugabe’s days in power, says those who took Dzamara would have been motivated by a political calculation to soil Mugabe’s image. In the militarised factions of internal Zanu PF politics, Mugabe was for a long time the proverbial glue which somehow kept the party relatively united. However, this changed when the Mnangagwa faction actively plotted against Mugabe, leading to the long-time ruler’s ouster by the military.

A senior bureaucrat told our investigation that the initial intention behind Dzamara’s abduction was not to kill him as such, but to intimidate him as the security apparatus had been spooked by his activism.

“When they took him, it is very probable they just wanted to rough him up and intimidate him. Dzamara had been arrested and beaten up countless times before. This time, coming soon after the big opposition rally at Zimbabwe Grounds, sections of the intelligence community saw Dzamara not only as a person of interest, but also a national security threat. But even then, the immediate idea wasn’t to eliminate him; the idea, it is clear, was to instil fear. In that process of intimidating him, something must have gone horribly wrong and he was paralysed and eventually had to be disposed of. This is what many people in government believe,” said the top official.

Footprints of the state

Zimbabwean police — even though tainted by selective application of the law and human rights violations — can be ruthlessly efficient when they want. Armed robbers are relentlessly hunted down and even shot dead.

The country does not have a history of ransom demands. Security experts acknowledge that almost all unsolved cases of abduction can be directly attributed to either the state or the ruling Zanu PF, which both enjoy political protection and impunity.

Wheels of death

In much of Africa, double-cab trucks are used as utility vehicles. They are convenient in transporting technical staff, tools and materials. The vehicles are largely bland, unremarkable contraptions and most people in the street would not look twice at a twin cab.

But in Zimbabwe, double-cab trucks have a sinister reputation. Journalists, human rights defenders, unionists, student leaders, opposition activists and civil society campaigners know that these vehicles can transport more than just hardware tools. They are the favoured mode of transport for enforced disappearances, extrajudicial detentions, torture, state-sanctioned killings and violent intimidation.

The number plates on these vehicles are either removed or obscured. In some instances, the trucks are outfitted with number plates taken from the scrapyard. The menace of unmarked and tinted twin cabs driven by armed agents of the state is not a fairy tale but a lived reality in Zimbabwe.

In rare instances, the abductors badly miscalculate by using double-cabs with genuine number plates. In one such instance, our investigative journalists recently traced the number plate of a twin cab to Impala Car Rental, a vehicle hire company partly owned by the Central Intelligence Organisation. The Ford Ranger, registration AES 2483, had been used in the abduction and gruesome torture of Tawanda Muchehiwa, a journalism student. Muchehiwa is nephew of Mduduzi Mathuthu, the editor of prominent online tabloid ZimLive and the real target of the state’s wrath after he had rattled the authorities by publishing news articles on corruption. State agents abducted Muchehiwa on the eve of the 31 July 2020 nationwide opposition protests. For three days, he was subjected to horrendous torture. He has since fled into exile.

Similarly, a truck was used in Dzamara’s abduction. It was described by eyewitnesses as a white truck with concealed number plates. An anonymous informant later stated that the truck’s registration number is ABG 2862. However, a search at the Central Vehicle Registry shows that the number plate belongs to a white Mitsubishi Canter truck registered in the name of Ishamel Matyenyika of Harare’s Sunningdale Two suburb.

There is a big difference between a typical twin cab and a 3.5-tonne Mitsubishi Canter truck. Matyenyika said he used to import Mitsubishi trucks between 2007 and 2011 and the vehicles were sold by his friend, only identified as Pastor Mutyamaenza.

The anonymous informant furnished police with several other leads, including the grave at Chikurubi Prison where Dzamara was allegedly buried. There was also an allegation that he had been tortured on a state farm on the outskirts of Harare. Police, through Assistant Commissioner Crispen Makendenge, claimed that these tip-offs yielded nothing useful. Makendenge has since left the police service.

Conclusion

Four years after ascending to power on the back of a coup d’état, President Mnangagwa’s government has not fulfilled its promises to chart a new path on democracy and human rights. The unsolved mystery over the enforced disappearance of journalist and pro-democracy activist Itai Dzamara is a stark reminder of this. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have recommended that the Zimbabwean government appoint a judge-led commission of inquiry into the matter. Dzamara deserves justice.