Today marks the 31st anniversary of the murder of the Colombian journalist Silvia Duzan, who was killed while in the pursuit of the most remarkable story of her life about drug trafficking, paramilitary squads and the group of peasants who dared to challenge them. She was gunned by the paramilitaries of the criminal group of Puerto Boyacá in Cimitarra along with three farmer leaders of the Association of Peasant Workers of Carare, (ATCC): Josué Vargas, Saúl Castañeda and Miguel Ángel Barajas.

She was fearless and despite numerous warnings and concerns of her family and of her production company, she was persistent in her desire to uncover the truth, which inevitably lead to her death.

Thirty-one years after there is still no justice. Her death and the death of the leaders of the Association of Peasant Workers of Carare, remain unsolved and their families are still fighting for justice.

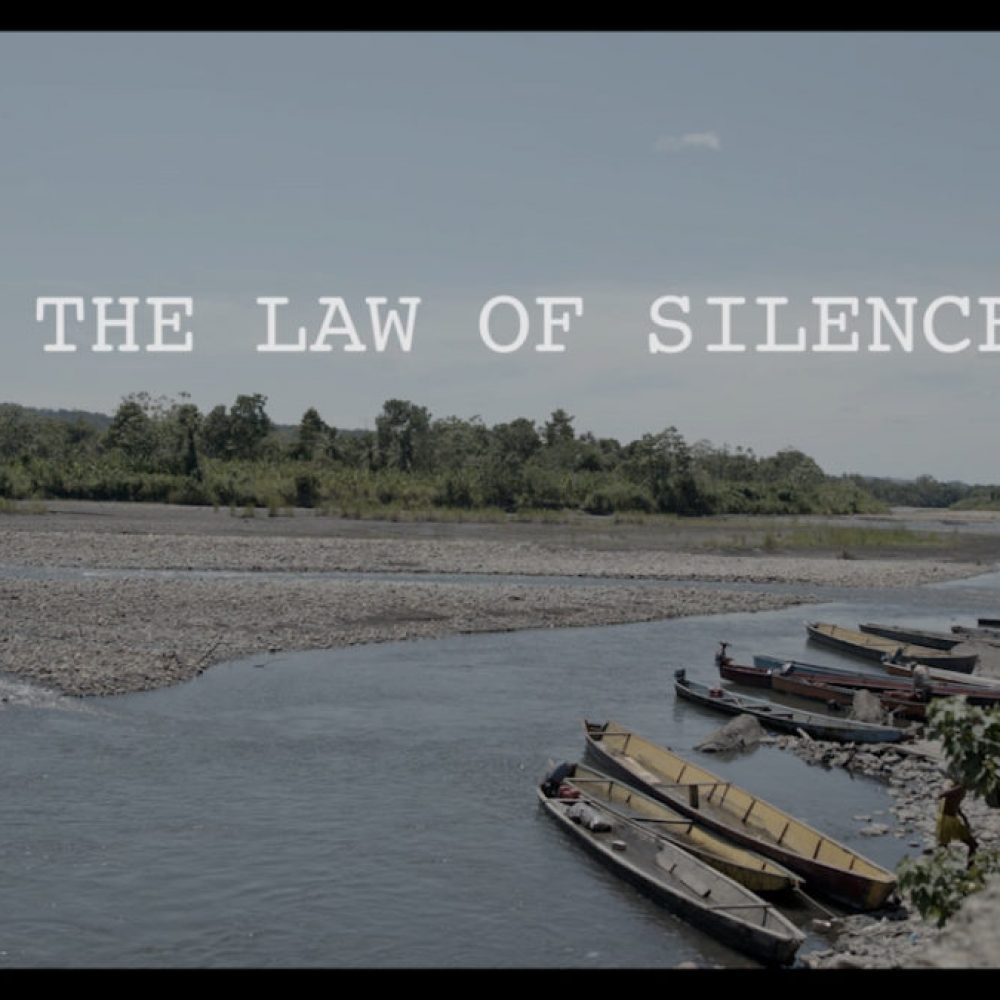

The story of Silvia Duzan is a symbol of a legal vacuum. During the time of Pablo Escobar, journalists in Colombia faced years of repression, especially between 1980s and 1990s, the darkest years of the country’s history. ‘Law of Silence’ is the story of passion, courage, ingenuity and ultimately injustice. Just like many other stories of journalists fallen in the line of duty during the war in Colombia, annihilating those, who dared challenging ‘The Law of Silence’.

The trailer of the ‘The Law of Silence’ documentary is available here.

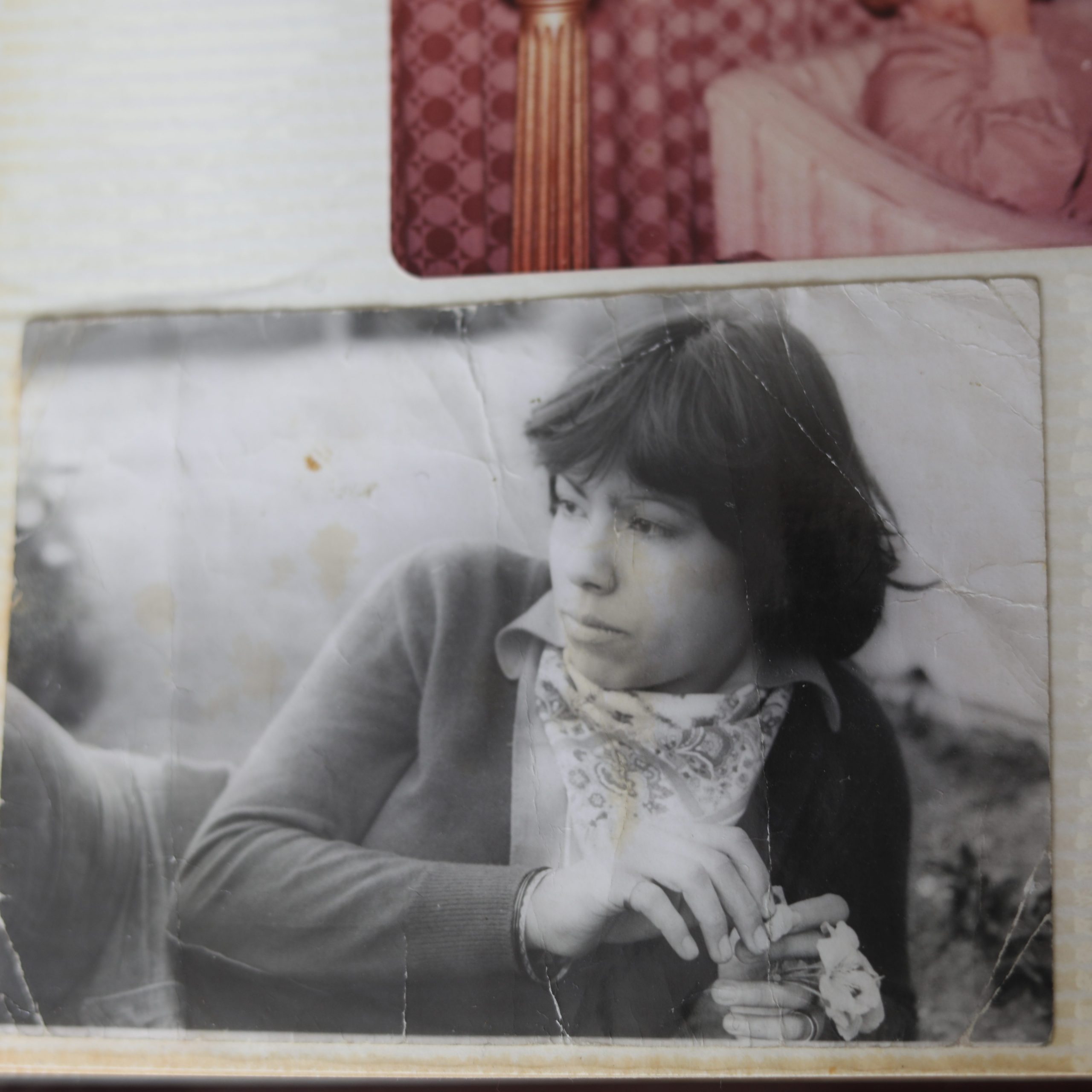

Silvia

Born into a long tradition of high-profile journalists, her grandfather’s family owned the prestigious liberal paper Vanguardia Liberal, in Bucaramanga. Her father Lucio Duzan became, by the 1970s, a prestigious political columnist, writing for the most influential paper in Colombia: El Espectador. Her sister, Maria Jimena Duzan, is today Colombia’s most outspoken and admired investigative journalist. Maria Jimena remembers how together with her younger sister Silvia she would squat at night at the top of the family staircase, where they would spy on the adults, often politicians and intellectuals, discussing till the early hours current affairs and philosophy in the living room of their house in Bogota ’. Every Sunday, the young Duzan sisters, would accompany their father Lucio through the ritual of visiting the headquarters of El Espectador. It was where the Editor Guillermo Cano received the pages written on the loud Remington typewriter, among the roaring sound of gigantic red printing machines, pressing and spewing out the freshly printed Sunday edition of the paper.

It was inevitable for the Duzan sisters to grow up with a passion for journalism. By the time their father died, it was the only viable profession they as teenagers could imagine. At 16, Maria Jimena followed her father’s footsteps and joined a small group of Investigative Journalists working with Cano for El Espectador, while her sister Silvia pursued her passion for music, urban ghettoes, sub-cultures and social underworlds, until she found herself roaming the dangerous underbelly of Medellin, a contender with Mogadishu, at the time, for the title of the most dangerous city in the world.

Medellin, today a backpackers’ paradise and a tourist Mecca, was in the 1980s the playground of a young ambitious politician and wannabe ‘philanthropist’, Pablo Escobar. Medellin was also, unbeknown to many at the time, as the headquarter of the illegal operations of his Medellin Cartel. Pablo Escobar Gaviria, that monstrous giant shadow that will eventually envelop the entire country and spread its tentacular sinister influence around the world, had already started taking over every aspect of Colombia’s life. At the time, Silvia was learning the most dangerous craft in her country by pursuing interviews with local sicarios and drug dealers, between the urban jungles of Comuna 13, barrio Juan Pablo and the squalid garbage dump that was barrio Moravia. Alonzo Salazar, Author and Politician, accompanied Silvia on some of her missions among the people of Medellin. He remembers her as ‘always smiling, a people person, who could disappear through narrow passageways and into houses for hours, while she listened to someone’s life story or gathered information, before suddenly emerging again from some shack or street corner, blissfully unaware of the alarm she had caused her frantic friends’.

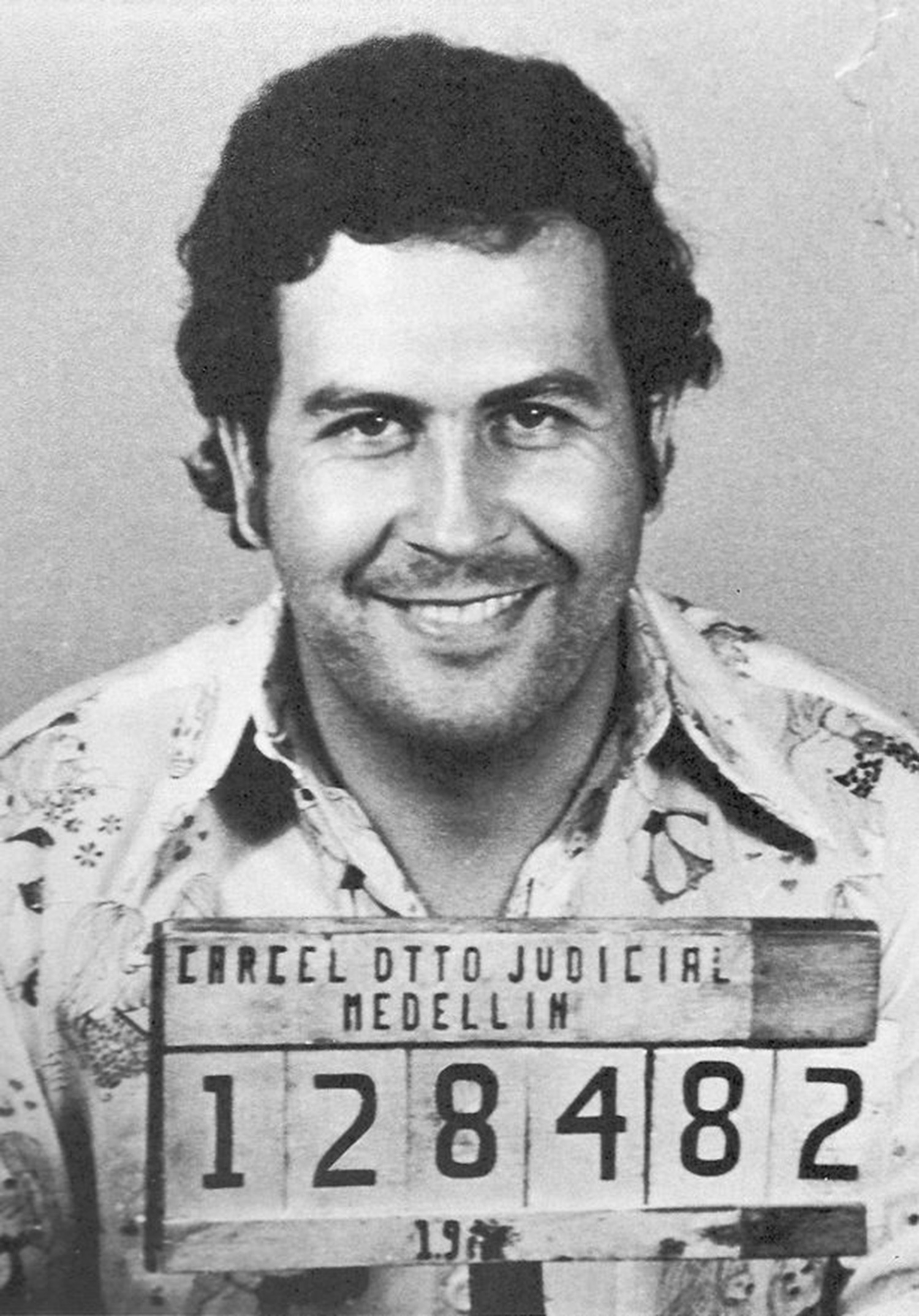

In 1986, Pablo Escobar was a Congressman of the Colombian Republic. He saw himself as the Robin Hood of Medellin and genuinely dreamed of becoming President of Colombia, until one Newspaper Editor and his investigative team, exposed his true nature of drug lord putting an end to his ambition and political career. It all happened overnight. One day Guillermo Cano, Editor of El Espectador, remembered an article published a decade earlier about a drug smuggling operation which culminated his arrest. He remembered the defiant mug shot of a smiling young Pablo Escobar among the criminals arrested during the operation. He wasted no time and unleashed his investigative team, including Maria Jimena Duzan into the paper’s archives, until they finally pulled out and published the most famous image of Congressman Gaviria, 10 years younger, holding arrest card number 128482 for the whole country to see.

According to Edgar “El Chino” Jimenez, Escobar’s personal photographer interviewed in the film: ‘This marks the beginning of the crusade Pablo declared against the journalists, who had unmasked him and the Colombian State that had rejected him’. Escobar’s war against the media didn’t spare the lives of: Editor Guillermo Cano, gunned down in 1986, the Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara and a long list of journalists and politicians, who had destroyed his political ambitions or threatened the Narco empire his Cartel had built behind his respectable political façade.

Silvia’s sister, Maria Jimena is on the list of targets to eliminate and she joins many of her colleagues in exile, while Silvia remains in Colombia and embarks on a new project, a documentary commissioned by the British Channel 4 and produced by the Colombian Citurna Producciones. The project takes her away from Medellin to one of the main production fields of the Medellin Cartel: El Magdalena Medio, a region of rivers, fertile land, thick green vegetation, on the frontline of the war between guerrilla forces and paramilitaries. It is here that she dives into and follows the story of her career, the story that will ultimately lead to her death.

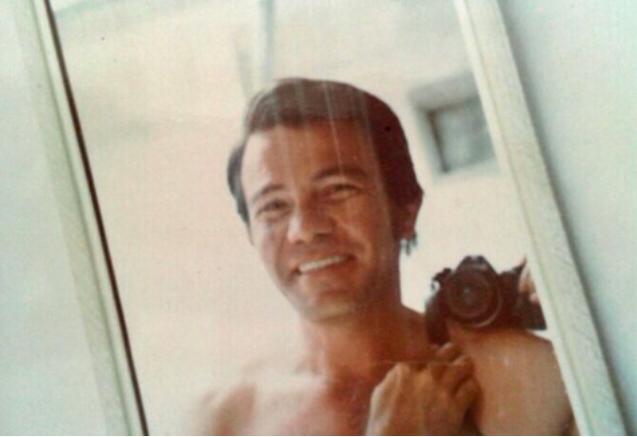

Silvia dives into the territory, meeting people in Magdalena Medio, following leads, testing the ground to look for characters and stories for the documentary that would be ultimately titled “Behind the Cocaine War”. She starts investigating the local drug production, links between paramilitaries, the army, the police, the cartels and the role of the guerrilla. She moves in an environment so volatile that looking at someone in the eyes could be a death sentence, in search of stories and characters she interviews guerrilla groups, local journalists and photographers. In the process, she meets photographer Jesus ‘Chucho’ Villamizar, a man who, by the time of his meeting with Silvia, had eluded death so many times, that many thought of him, as a walking target. He tells Silvia the story of The Massacre of la Rochela, in which 15 Judicial Officials, who were investigating crimes committed in the area of Simacota, were brutally killed. The guns were still smoking, when Chucho arrived on the scene to take the only photos of what remained of that judicial investigation: the bodies, the broken glass, the blood on the ground, the silence that followed every massacre.

Silvia had quickly worked out the connections between paramilitaries, guerrilla, the Army, the local Police and the links of all of them to the cartels. She asked questions, she talked to everybody, she followed every lead. Of all the stories she followed, one stood out, one she had heard from her sister Maria Jimena.

A group of leaders campesinos had achieved the impossible in the heart of Magdalena Medio, by convincing guerrilla and paramilitaries to a truce via non-violent means of dialogue and uncompromising determination. They had dared to stand up unarmed to the dark forces around them and they had succeeded in creating a small peaceful utopia called La India, on the banks of the river Carare, near a small town called Cimitarra. They had, against all odds, achieved a truce in the middle of the bloodiest conflict of their time.

The visionary force behind the group was Josue’ Vargas, a partially blind charismatic local peasant leader, tired of guerrilla and paramilitaries taking advantage and regularly killing local peasants, who failed to comply to one group or the other. Vargas recruited a group of competent idealists, who shared his non-violent, uncompromising approach and mobilised the community behind the principles of work, peace and prosperity for the region. He found his match in Miguel Angel Barajas, a sophisticated agronomist, writer, poet, philosopher and together they started a local revolution against paramilitaries, guerrilla, the Army, the Police, in other words: the cartels.

By the time Silvia arrived in Cimitarra for the first time, they had reached a truce with both guerrilla and paramilitaries and had successfully achieved prosperity in a region. Previously where bodies could be seen regularly floating down the Carare river, unclaimed even by the families for fear of revenge. Hundreds of thousands of people had disappeared or had been murdered in the space of 10 years. Silvia had met them in Cimitarra on numerous occasions, and she was determined to find out more about their incredible story. ‘Silvia thought this was the story of her life.’, Maria Jimena remembers, ‘It was a story of optimism in a country in which we were fed pessimism on a daily basis’.

Silvia’s last journey to Cimitarra had the bitter flavour of inevitability, of those occasional unavoidable appointments with destiny some remarkable biographies seem to be made of. On the eve of February 26, 1990, everybody tried to discouraged Silvia from going to Cimitarra. It was election time and both her mother and sister expressed concern for Silvia’s safety, knowing she was determined to go and meet interviewees. ‘Cimitarra is at its most dangerous when elections are near’, her mother had warned her but Silvia had shrugged off her worries: ‘If it has to happen, it will happen’. In a country like Colombia in the 1980s the prospect of death was a familiar companion, a daily possibility, a frequent occurrence and Silvia went out of her way to make her appointment with death in Cimitarra. She was also under strict orders from her producers at Citurna not to go to Cimitarra. They had been alarmed by her latest faxes from Magdalena Medio. The situation was deteriorating, they felt like it was getting too volatile, too dangerous.

Silvia argued with them days before her departure. She screamed down the phone when they wouldn’t pay for her flight, then she left a note to say she had an appointment with the leaders and that they were coming from La India to Cimitarra only to meet her and that she couldn’t let them down. She was going no matter what. Her determination to be there was so great that, when she realized she had missed her flight on the day of her departure, she jumped out of her husband’s car, which was stuck in one of the many traffic jams that so often paralyze Bogota’. She made her way on foot to the bus terminal. She finally arrived in Cimitarra when it was already dark, passed 8 pm. She joined the peasant leaders, who had waited for her all day. Witness at the trial will testify that people had seen paramilitaries and two known assassins in town and many had warned Josue’ Vargas, Saul Castaneda and Miguel Angel Barajas and begged them to be careful. However, they felt safe in Cimitarra, they ignored the warnings and they kept waiting for Silvia.

At around 9 pm, Silvia finally arrived and joined them at the restaurant La Tata. They order drinks, Silvia put her cassette recorder on the table when two men walk in and kill her, Josue’ Vargas, Miguel Angel Barajas and Saul Castaneda. Their murders are still unsolved. In a cruel twist of fate, The Association of Peasant Workers of Carare won an alternative Nobel Peace Prize a few months after the death of their leaders and Silvia. In the words of Hector Barajas: ‘We felt great pride, but also great pain, to see their work recognised internationally and to know that so many wanted them dead, because they were brave, because they didn’t abide to the Law of Silence.’

THE CASE

Thirty-one years on, almost all judicial options available in Colombia have been exhausted, but the families are still fighting for justice. The case is currently stuck with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and awaiting a resolution. In the similar case of La Rochela vs Colombia, the Court ruled against Colombia for its part in the violations. The Country partially accepted responsibility in the impunity that followed. We hope the documentary ‘The Law of Silence’ will prove a powerful advocacy tool towards justice in the murder case of of Silvia and the leaders of the ATCC, which so much echoes La Rochela Massacre.

THE LAW OF SILENCE

The Law of Silence is an investigative documentary currently in the post-production. With the help of the victims and some of the surviving protagonists, we finally pieced together the amazing story Silvia died for. We discovered new evidence, interviewed eyewitnesses, who spoke for the first time and reconstructed what really happened on February 26, 1990.

With the support of the international organizations for the protection of human rights: Justice for Journalists Foundation, Press Freedom Unlimited and the Right Livelihood Award, the film aims at remembering the victims and presenting new decisive evidence, as well as gathering support behind the quest for justice. Its ultimate aim is to lead to the resolution of the judicial case.

Inspired by the book Mi Viaje al Infierno by Maria Jimena Duzan, ‘The Law of Silence’ is expected to be released later this year.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Paola Desiderio is an international documentary Producer and Director, currently based in London. She specialises in investigative documentaries, human rights, history, crime, war, peace and conflict. She has directed and produced documentaries for the BBC, National Geographic, Netflix, Discovery, Channel 4, History, ITV, Amazon and many others.