AUTHORS OF THE REPORT

The Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ), is a non-governmental, non-profit and non-partisan association of media workers, promoting freedom of expression and independent journalism ideas in Belarus.

The main goal of BAJ is to facilitate the exercise of civil, social, cultural, economic and professional rights and the pursuit of legitimate interests of its members, help to develop expertise and get a chance for creative self-fulfillment, as well as to create conditions that enable freedom of the press, including the journalists right to obtain and impart information without any interference.

The main tasks of BAJ activities are:

- BAJ protects journalists’ rights and legitimate interests in state bodies and international organizations;

- BAJ helps to create material, technical, organizational and other facilities, vital for improving journalist proficiency;

- BAJ is drawing up an effective program to develop mass media so that it would create favorable conditions for their functioning in Belarus;

- BAJ establishes relations with journalist organizations all over the world.

Justice for Journalists Foundation is a London-based charity whose mission is to fight impunity for attacks against media. Justice for Journalists Foundation monitors attacks against media workers and funds investigations worldwide into violence and abuse against professional and citizen journalists. Justice for Journalists Foundation organises media security training and creates educational materials to raise awareness about the dangers to media freedom and methods of protection from them.

- Russia: Association Grani

Association Grani (France) – an NGO established to combat Internet censorship. In 2015, the jury of the French national human rights award “Freedom. Equality. Brotherhood” awarded Association Grani for its contribution to the fight against censorship in Russia.

The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (NUJU) is the biggest organisation that brings together journalists and other media workers in Ukraine. The union is an independent public non-profit organization. The mission is the development of journalism and media in Ukraine and protection of freedom of speech and journalists` rights.

NUJU cooperates with international organizations and institutions of the United Nations, the EU, the Council of Europe, the International Federation of Journalists, the European Federation of Journalists, the RFS (Reporters Without Borders) and communicates with foreign professional media organizations, concludes agreements with them on cooperation in the field of professional activity, exchange of information, establishment of journalistic exchanges (Poland, Belarus, China, Lithuania, Germany, Italy, etc.).

NUJU conducts conferences, public hearings on the topic of freedom of speech and the safety of journalists, actively participates in the preparation of changes in the Ukrainian media-law, provides legal support for journalistic activities, co-organizer of different forums, festivals, promotions, press tours, seminars, etc.

- Photographers

The Belarusian Association of Journalists (Belarus); Ludmila Savitskaya, Andrey Zolotov (MBK Media, Russia); The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine (Ukraine).

INTRODUCTION

This report forms part three of a cycle of research studies on attacks against media workers in the 12 post-Soviet countries over the period from 2017 through 2019. As used in this report, the term “media workers” refers to journalists, bloggers, camera operators, photojournalists, and other employees and managers of traditional and unregistered media. This section of the study is devoted to Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine.

The report does not cover attacks against professional and citizen journalists in Crimea; statistics on assaults in this region have yet to be incorporated into the Media Risk Map. Full information about this topic can be found in the report Chronology of pressing the freedom of speech in Crimea, put together by the Crimean Human Rights Group and the Human Rights Centre ZMINA and published on February 9, 2020.

Assaults on media workers in the three Slavic states are being examined in a single report not only because of the geographic proximity and cultural similarity of these countries, but also to make it more convenient to compare the methods of suppressing freedom of speech that prevail in them.

METHODOLOGY

The data for the study have been obtained from open sources in the English, Belarusian, Russian, and Ukrainian languages using the method of content analysis. Lists of the main sources are presented in Annexes 2-7.

Based on further analysis of 3,063 incidents of assaults on professional and citizen journalists, bloggers, and other media workers, as well as on the editorial offices of traditional and online publications, three basic types of attacks have been identified:

- Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health

- Non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats

- Attacks via judicial and/or economic means

Each of the types of attacks presented is further divided into sub-categories, a complete list of which is presented in Annex 1.

PRINCIPAL TRENDS

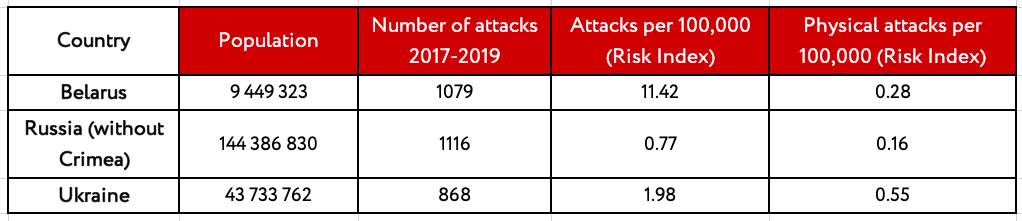

The total combined population of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine numbers nearly 200 million people, which corresponds to approximately 45% of the population of the European Union. For a proper analysis of the risks of assaults on media workers, it would be advisable to look at not the absolute numbers of attacks, but at the relative figures: per 100 thousand people. According to calculations, journalists from Belarus are subject to the greatest risk of assault, although the risk of physical assault is higher in Ukraine.

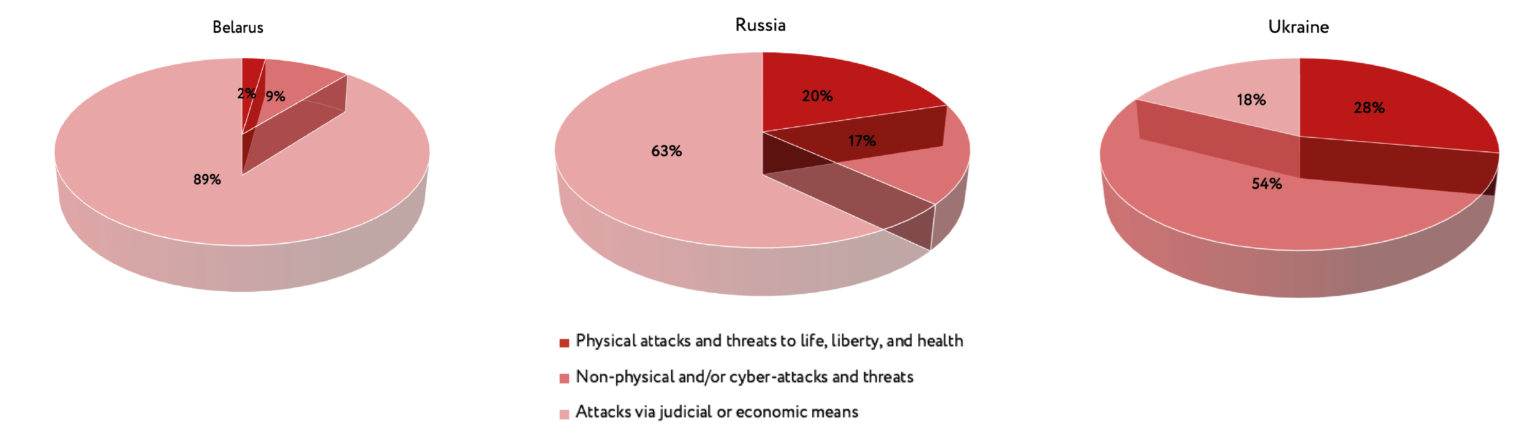

Belarus holds second place after Armenia among the 12 post-Soviet countries in terms of the relative number of attacks against media workers per 100 thousand people, with a risk index of 11.4. The principal method of assaults on journalists in Belarus are attacks via judicial and/or economic means – these comprise 89% of the total. The principal source of danger for media workers are the authorities – above all the police and the courts. A “package” form of attacks predominates in Belarus, in the course of which a media worker is detained short-term, tried, and arrested for 72 hours and sentenced to payment of a fine. The most frequent “administrative offence” is cooperation by Belarusian freelance journalists with foreign media without Foreign Ministry accreditation. Sometimes searches of a journalist’s work premises and residence with confiscation of equipment and documents form a component part of such a “package attack”.

Russia, along with Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan, exhibits indicators of relative risk of being subjected to assault that are not high for post-Soviet countries – 0.77. However, for Moscow, with a population of 12.5 million persons, this risk comprises a considerably higher 2.95. It may be assumed that such numbers can be explained by the peculiarities of monitoring assaults in this country. Russia stands out with its high number of deaths among media workers: 15 people perished as the result of murders, accidents, beatings, and suicides, a number twice as high as in all 11 post-Soviet countries taken together. The most widespread type of assaults on media workers in the country are attacks via judicial and economic means. The number of recorded short-term detentions of journalists by police in the period covered in this study exceeded 200 incidents, while 40 journalists were sentenced to various terms of deprivation of liberty.

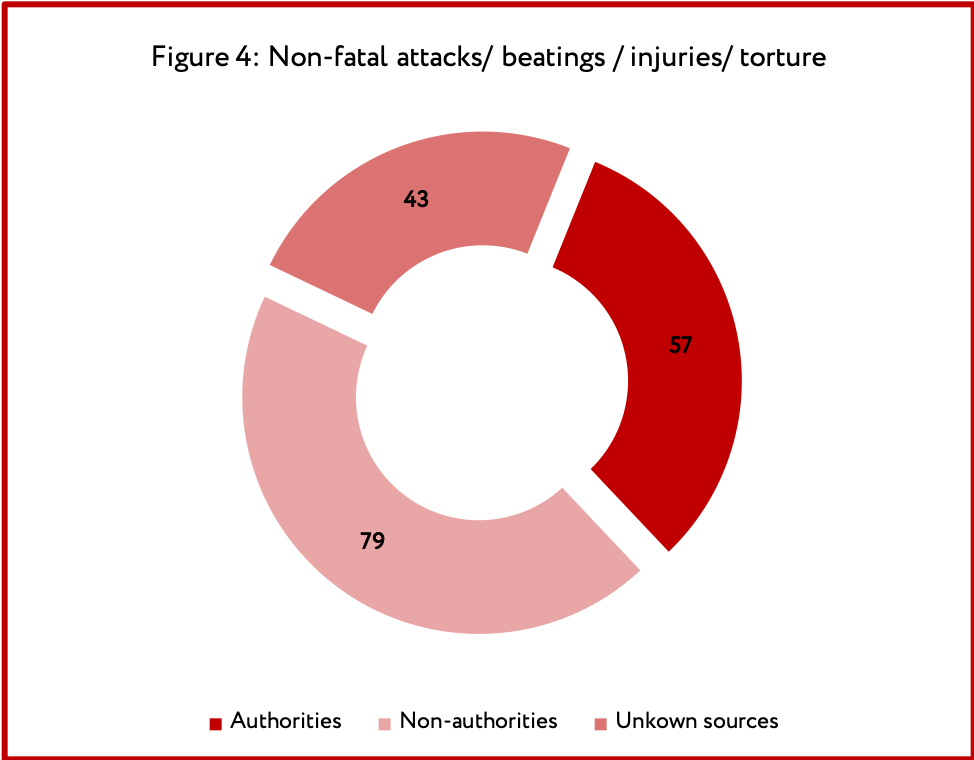

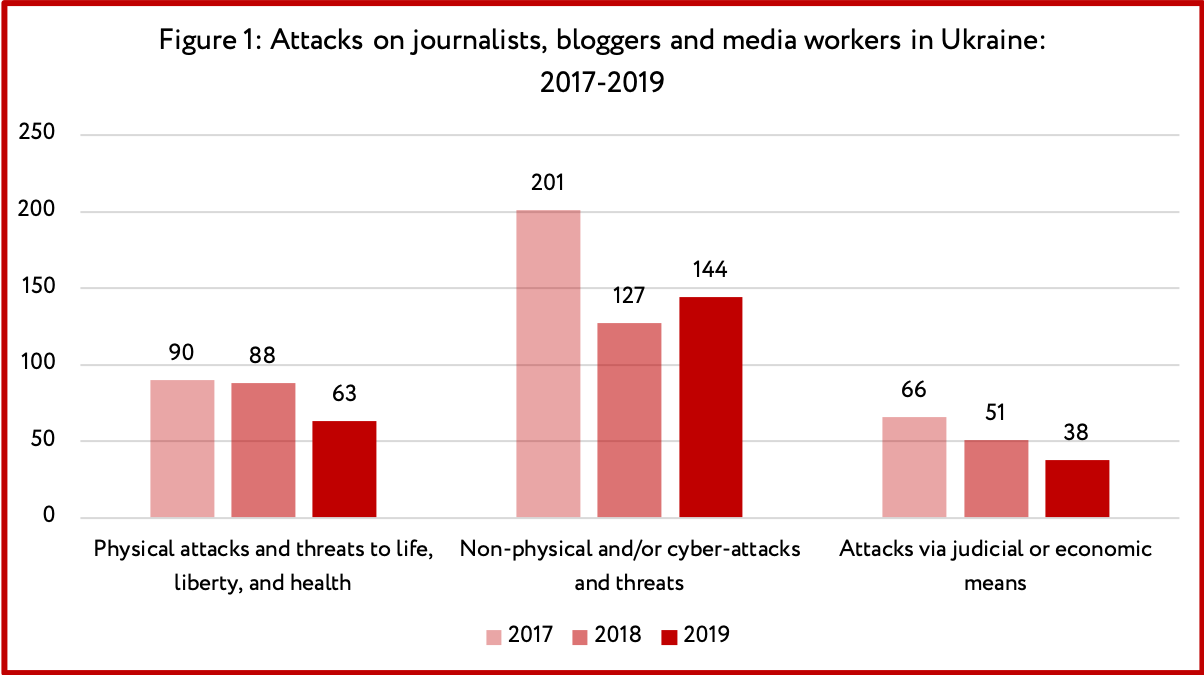

In Ukraine, the relative index of attacks against journalists comprises nearly 2 per 100 thousand people, which puts the country in sixth place among the 12 post-Soviet countries in terms of degree of risk for media workers, between Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. It should be noted that in zones of combat activities – Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts – 43 assaults on journalists have been recorded, while in Kiev Oblast the number is 385. Nearly 28% of all recorded assaults on media workers in Ukraine consist of attacks of a physical nature (beatings, abductions, attempted murders). Moreover, in more than half of the cases, those committing the assaults were not connected with the authorities. In this country, the prevailing methods for pressuring journalists are bullying and intimidation, including in cyberspace, as well as damaging and seizure of property and documents. The decline in the overall number of attacks from 357 in 2017 to 245 in 2019 gives cause for optimism.

RISK REDUCTION MECHANISMS

Analysis of the risks for media workers, as well as of their geography, frequency, and sources, is a necessary precondition for working out methods of protection and safeguards. Even taking into account the limitations associated with the ability to track assaults on media workers, analysis of the data obtained allows us to offer several recommendations for more effectively withstanding attacks in each of these countries.

- In Belarus, the source of the attacks on journalists in the overwhelming majority of cases is the authorities, while the function of the courts usually comes down to rubber-stamping a repressive decision that has already been adopted. That said, there is a rather effective system of monitoring attacks in place in Belarus, a country where the president has been in office for more than 26 years already and independent media inside the country have been practically annihilated while Belarusian journalists are subjected to harsh administrative and even criminal prosecution for cooperation with foreign publications.

In these conditions, public disclosure of incidents of assaults on journalists, drawing public attention, payment of fines, and in the event of repeated targeted attacks, leaving the country and continuing to work abroad, present themselves as the most effective methods of protection.

- In Russia, the risks for media workers are increasing with each passing year and come above all from the authorities, who regularly deprive professional and citizen journalists of liberty and beat them up. Besides that, the adoption of ever more repressive laws is expanding the arsenal of methods of “judicial” influence on independent media, compelling an ever greater number of journalists to leave the profession. In the meantime, the number of fatal incidents, attempted murders, beatings, and torture of journalists growing, while the investigations of these incidents remain at an unsatisfactory level.

Recording the various types of attacks on independent publications and journalists has important significance for a more precise assessment of the risks. Drawing public attention to violations of the rights of media workers remains the most effective method of protecting Russia’s journalists. Besides that, it is extremely important to provide them with timely and professional legal assistance. Inasmuch as one fifth of all attacks are connected with beatings of journalists, training courses on physical security would allow for a reduction in the risk of physical assaults.

- In Ukraine, the overall number of attacks on journalists is dropping, but the risk of physical assaults nonetheless remains high. Monitoring of threats and non-physical attacks is efficiently organised in this country, which is instrumental in intensifying vigilance on the part of journalists. It is perhaps on account of this that it is proving possible to prevent some portion of the more egregious crimes. That said, the work of the courts in investigating crimes against journalists and finding and punishing the perpetrators does not seem to be effective.

In such conditions, the work of improving the monitoring of assaults ought to be continued, as should the informing of broad strata of society about the situation and the adoption of the necessary measures of protection, including protection by the state. Besides that, training courses on physical and cyber security for journalists have proven useful.

The Justice for Journalists Foundation, together with its partners and experts, carries out weekly monitoring of attacks against media workers in all post-Soviet countries excluding the Baltic states, the results of which are published on the Media Risk Map in both Russian and English. The available data covers the period from 2017 onwards.

Belarus

1/ KEY FINDINGS

1,079 incidents of attacks/threats in relation to professional and citizen media workers and editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Belarus were identified and analysed in the course of the study. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Belarusian, and English languages using the method of content analysis. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 2.

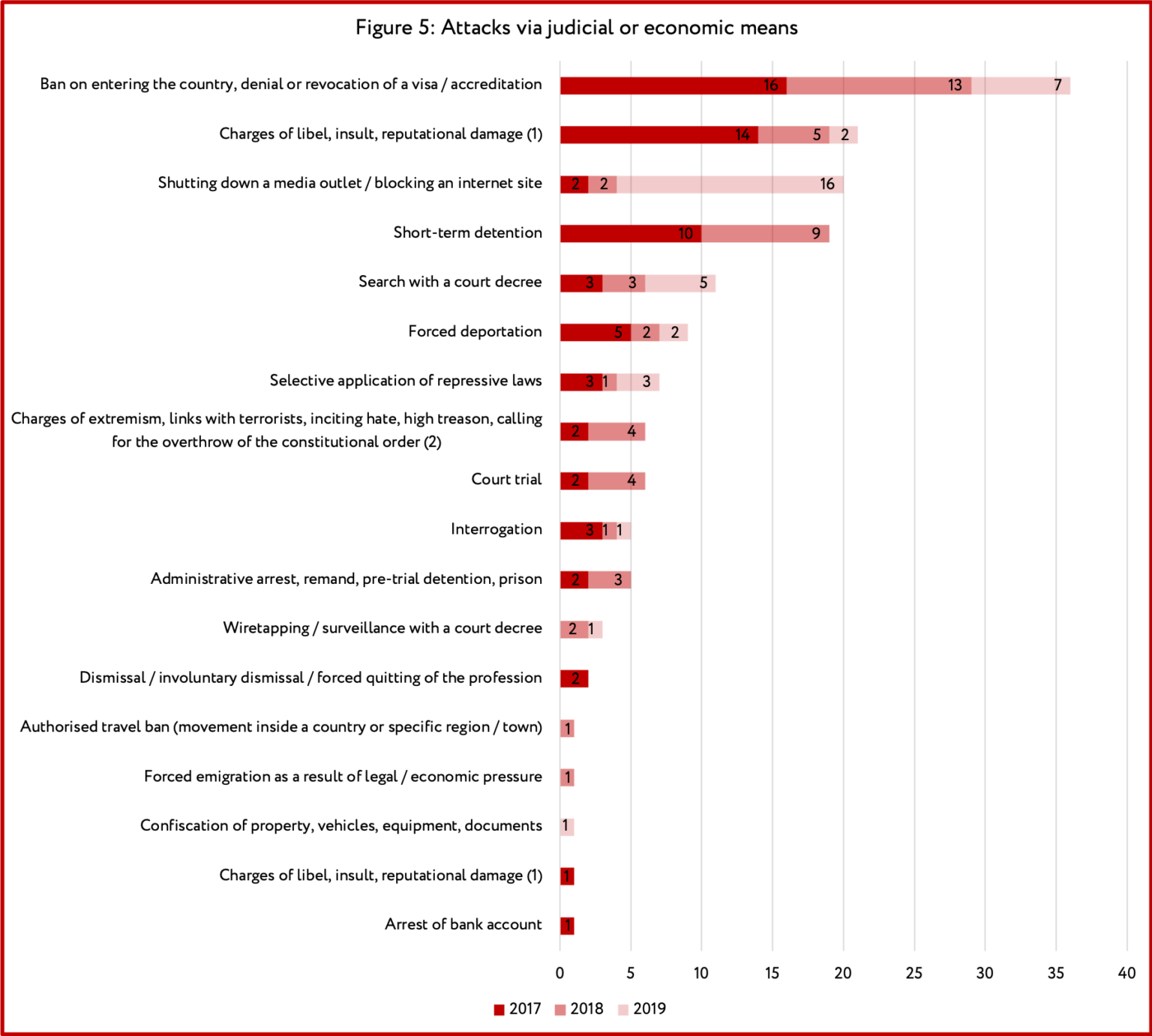

- Attacks via judicial and/or economic means are the most widespread form of pressure on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in Belarus. 957 incidents in this category were recorded.

- The most prevalent method of attack via judicial and/or economic means is fines for cooperation with foreign media without Foreign Ministry accreditation. The number of incidents in this sub-category is 236.

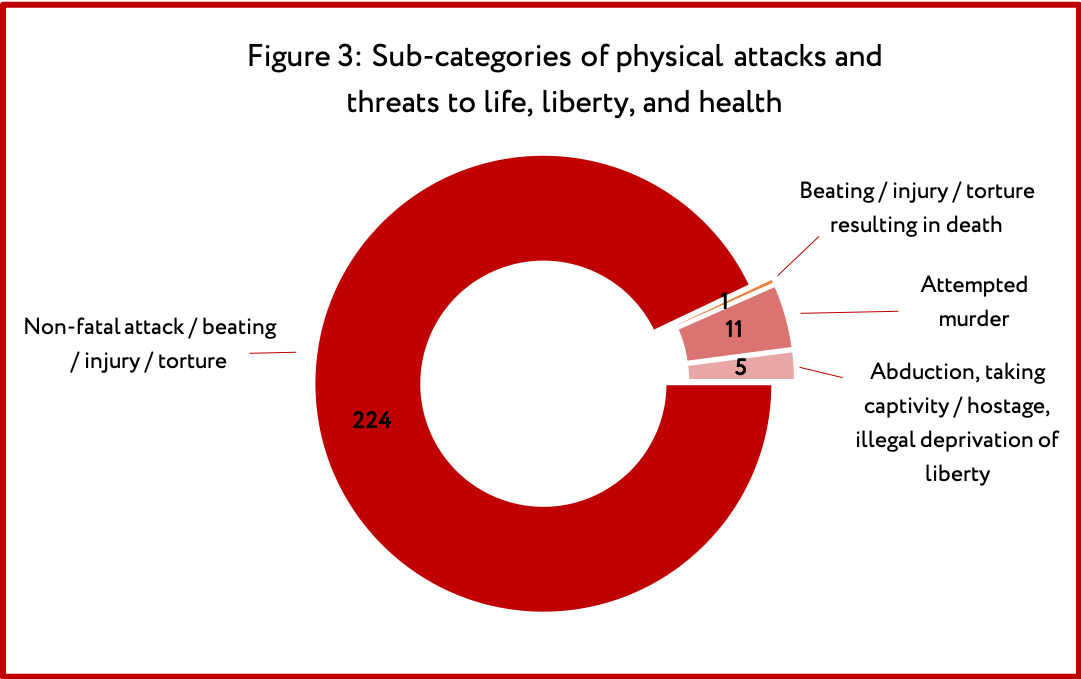

- The number of physical attacks in Belarus is very low in comparison with other countries in the post-Soviet space. 26 attacks in this category were recorded over the period covered in this study.

- The BelTA case is the most high-profile criminal case to be brought against a media workers in Belarus in the years 2017-2019.

- Most often it was freelance journalists working for the satellite television channel Belsat who were subjected to attacks – in 623 of the 1,079 recorded cases.

2/ THE MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS. THE BRIEF OVERVIEW.

Registration of print media in Belarus, just like television and radio broadcasters, is mandatory and by license, and is exercised by the Ministry of Information. According to data provided by the agency, 1,614 print media outlets were registered in Belarus as of January 1, 2020. Of these, 435 print publications are state-owned, which allows the Belarusian authorities to state that private media predominate in the country. However, the vast majority of non-state-owned print media are strictly entertainment and advertising. According to the data of the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ), there are no more than 30 registered non-state-owned media outlets of a socio-political nature. Nearly half of these were removed from the state’s newspaper subscription and retail distribution networks as far back as 2005, and only in 2017 were they put back on the distribution lists of the state monopoly distribution enterprises (approximately 15 publications had ceased publication by this time).

At the same time, state-owned media receive not only administrative support and various kinds of preferences, but also public funding given out on a non-competitive basis. In 2019, the sum of such funding exceeded 72 million US dollars. The bulk of these funds (over 50 million dollars) were earmarked for the funding of the Belteleradiocompany [the state-owned broadcaster].

The situation with television and radio broadcasting in Belarus meets democratic standards even less. Of the 270 registered television and radio programmes, the overwhelming majority (188) belong to the state. The remaining 82 non-state-owned television and radio stations are under the complete control of the authorities, both local and national, by virtue of the registration and licensing system.

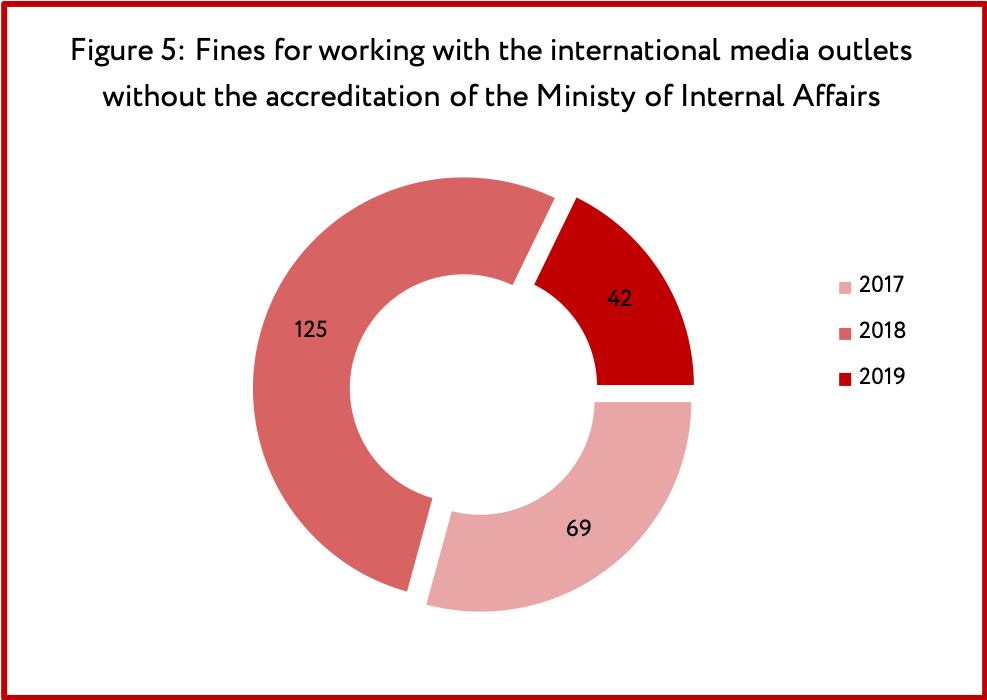

Foreign stations disrupt the state’s monopoly on broadcasting. Radio Liberty, European Radio for Belarus, Radio Racyja, and the satellite television channel Belsat play a particular role (the latter three media outlets listed are registered in Poland). Their programmes are aimed at Belarusians and are prepared primarily by Belarusians. However, neither Belsatnor Radio Racyja have legal status in Belarus, despite efforts to open news offices and obtain accreditation for their journalists. Freelancers working with them come under constant pressure on the part of the authorities. Since 2014, they are being fined for “violation of the order for production and distribution of media output” (Article 22.9 of the Code of Administrative Offences). Based on police reports, in the years 2017-2019 freelance journalists were fined 231 times for working with foreign media without accreditation, for an overall sum equivalent to nearly 100 thousand US dollars. For reference, the average monthly salary in Belarus is around 500 dollars.

The internet remains the freest information space in Belarus. According to data from a study conducted by the Informational-and-Analytical Centre under the president’s administration, in 2017-2018 around 60 percent of respondents were receiving their news from the internet (72% from television), while among young people this percentage was significantly higher. Moreover, the majority of the ten most popular internet sites is made up of non-state-owned sites.

The Belarusian authorities reacted to the growing significance of the Internet by tightening control over it. At the end of 2017 and the start of 2018, by decision of the Ministry of Information, two popular news sites in Belarus were blocked: Belorussky partizan [Belarusian Partisan] and Khartiya 97 [Charter 97]. In 2018, criminal cases were opened against key players in this sphere (most notably the “BelTA case”; see Section 5 “Attacks via judicial and/or economic means”), and several popular regional bloggers came under pressure (in the form of criminal cases, administrative prosecution, and threats). Changes were introduced to legislation to tighten state regulation of the Belarusian segment of the World Wide Web. In particular, identification of users of internet sites was made mandatory, pre-moderation of comments was effectively introduced, and the culpability of website owners was increased. The new law allows for the voluntary registration of internet sites as media outlets (online publications), but this registration procedure has remained costly and complicated. Despite the fact that internet sites not registered as online publications are not now considered media outlets, and their journalists cannot enjoy the corresponding status, only 6 non-state-owned sites had gone through registration at the Ministry of Information as of January 1, 2020 due to the complexity of the registration requirements and the unclear benefits to be gained from this registration in the current circumstances.

In the annual World Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders for 2020, Belarus ranks 153rd out of 180 countries.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

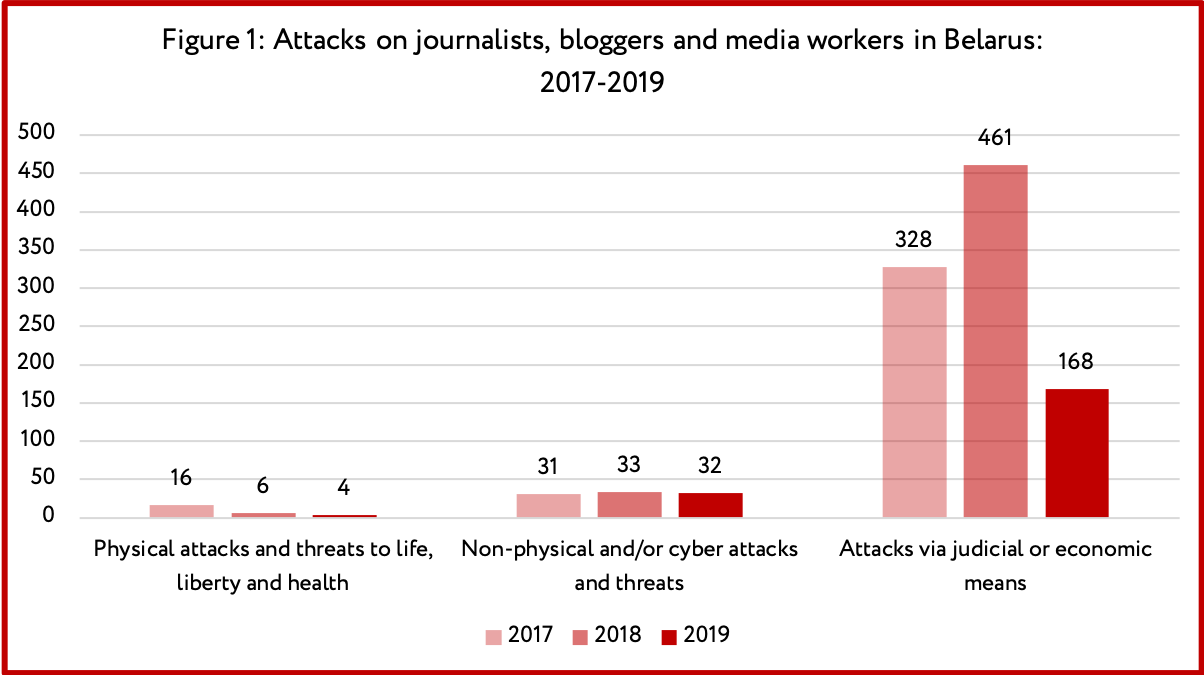

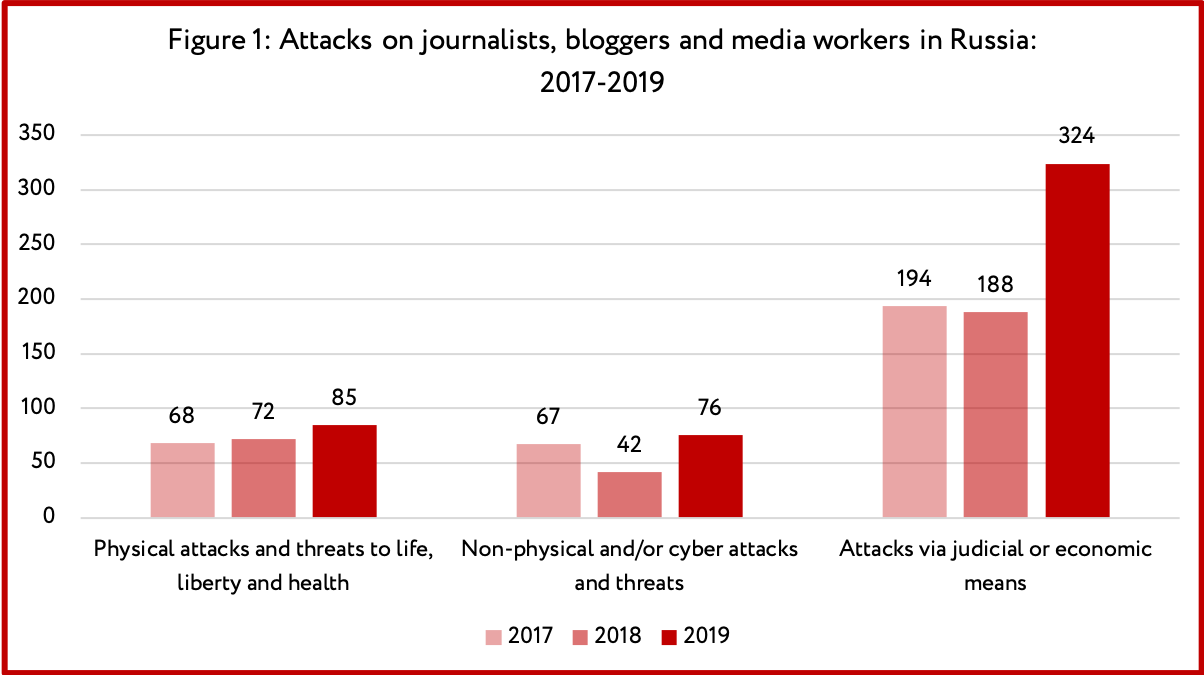

Figure 1 presents a quantitative analysis of the three main types of attack perpetrated against journalists in Belarus in the period from 2017 to 2019. The principal type of attack against journalists, bloggers, and media workers were attacks via judicial and/or economic means. These comprised 88% of the overall number of attacks captured in this study: 957 out of 1079.

The number of attacks of this type correlated with the change in the country’s political and economic situation. The increase in protest sentiments and mass demonstrations in Belarus also gave rise to intensified pressure on the media, journalists, and bloggers covering them. Thus, the peak of short-term detentions of journalist (93 people) in the period covered in this study occurred in 2017, when mass demonstrations against an unpopular presidential decree regarding the establishment of a special tax for unemployed people took place in all of the regions of the country.

During the period covered in this study, it was most often journalists from the satellite television channel Belsat who were the target of attacks – 623 out of the 1,079 recorded incidents. A number of journalists from the television channel experienced systematic pressure on the part of the authorities: Konstantin Zhukovsky (76), Olha Chaychits (59), Andrey Kozel (40), Alexandr Levchuk (36), Andrey Tolchin (34), Ekaterina Andreyeva (33), Dmitry Lupach (32), Milana Kharitonova (31), Larisa Shchiryakova (29), Sergey Kovalev (22), Lyubov Buryanova (Luneva) (19), Sergey Kvarchuk (16), Irina Orekhovskaya (13), Alina Skrabunova (12), and Alexandr Borozenko (11).

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

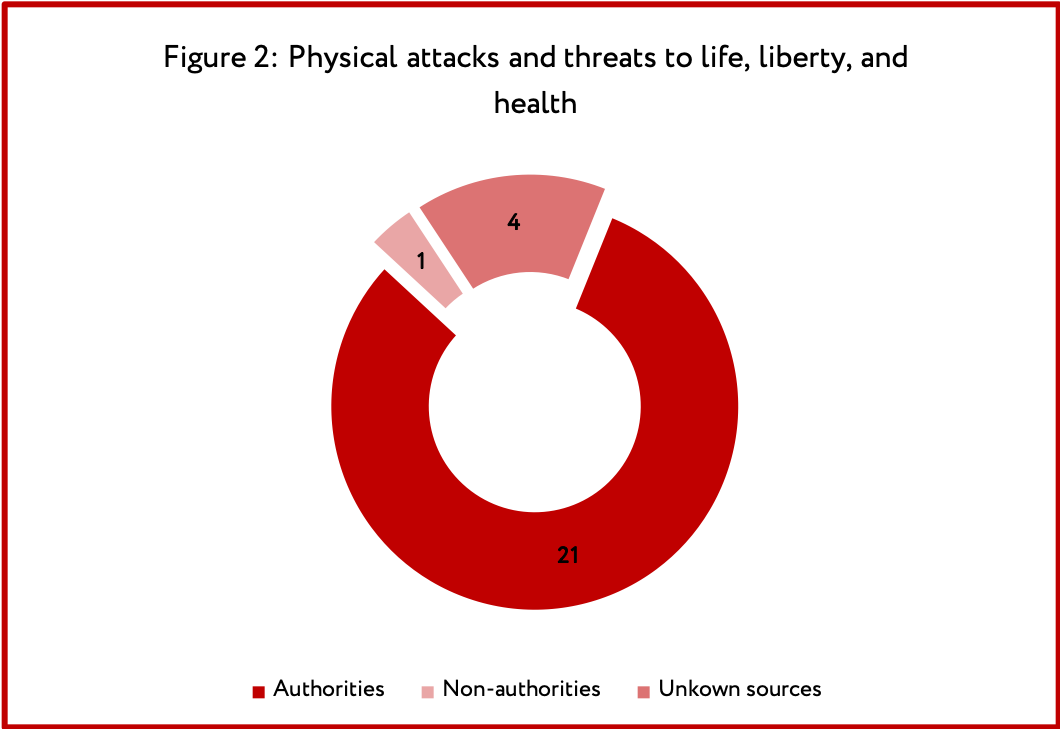

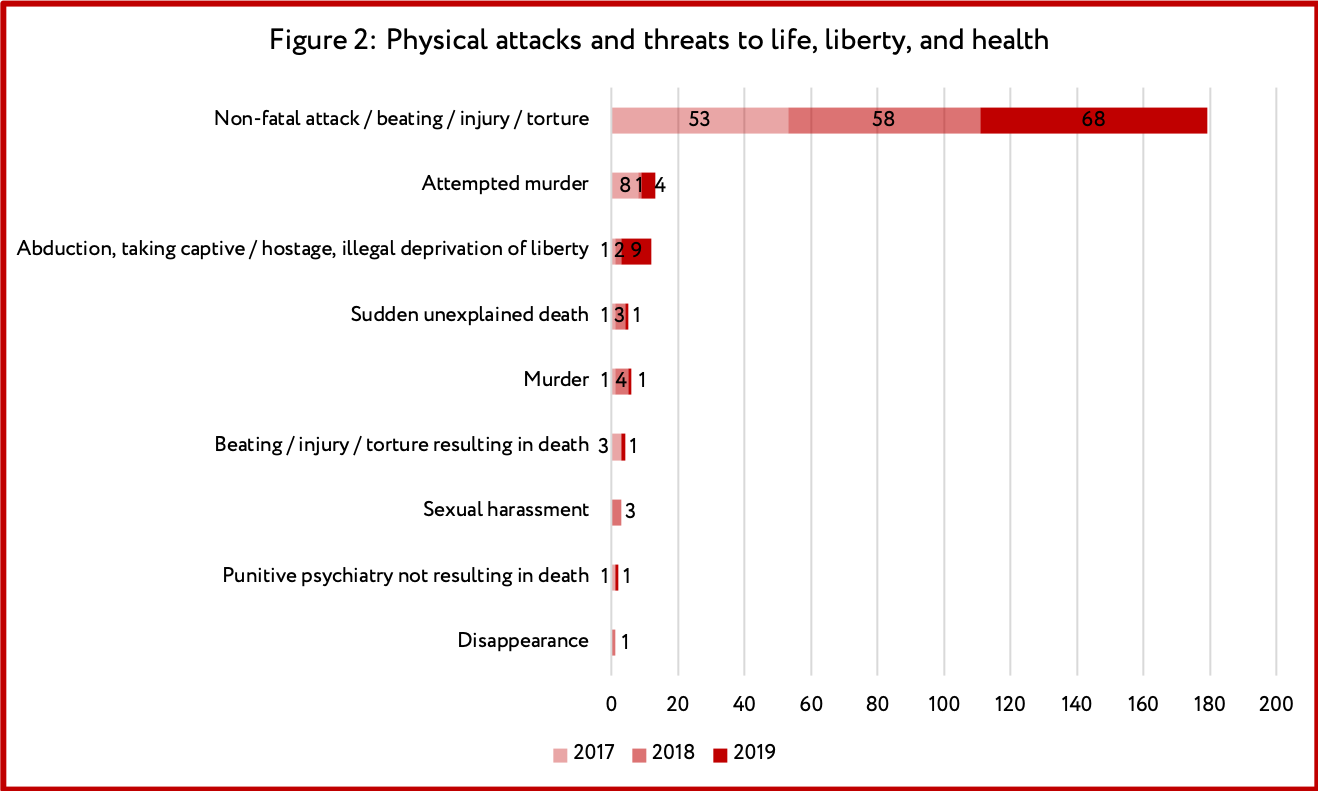

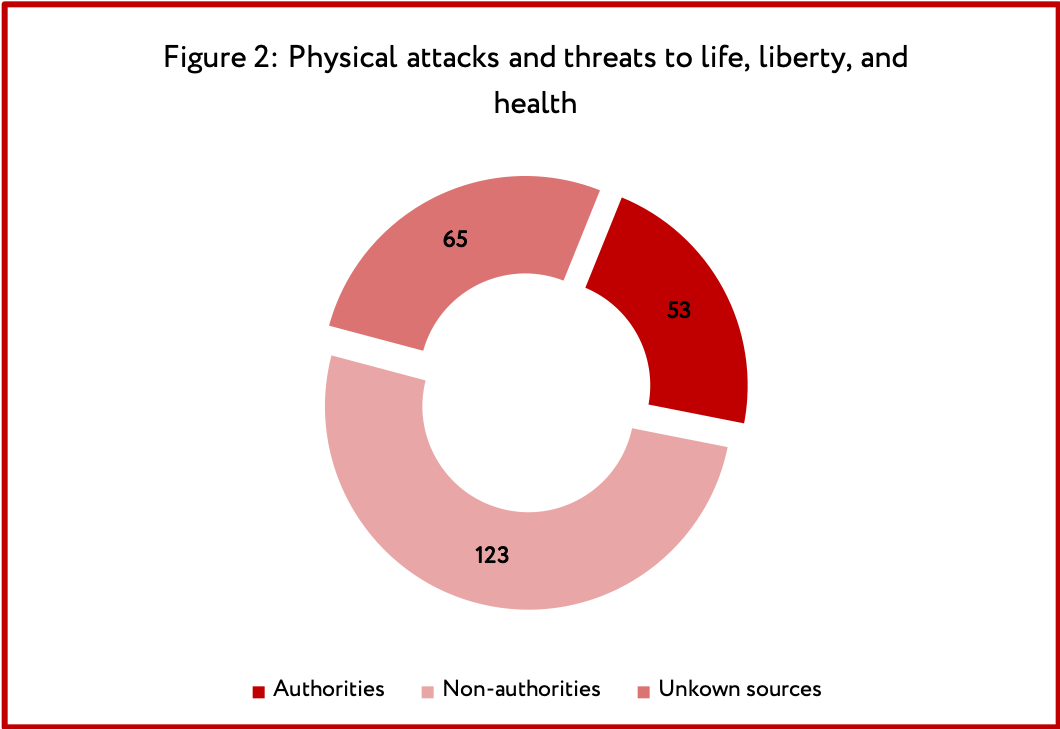

The number of physical attacks on journalists in the period covered in this study was comparatively low at 26. As has already been noted, the majority of them (16) occurred during 2017, when mass protest actions were taking place in Belarus.

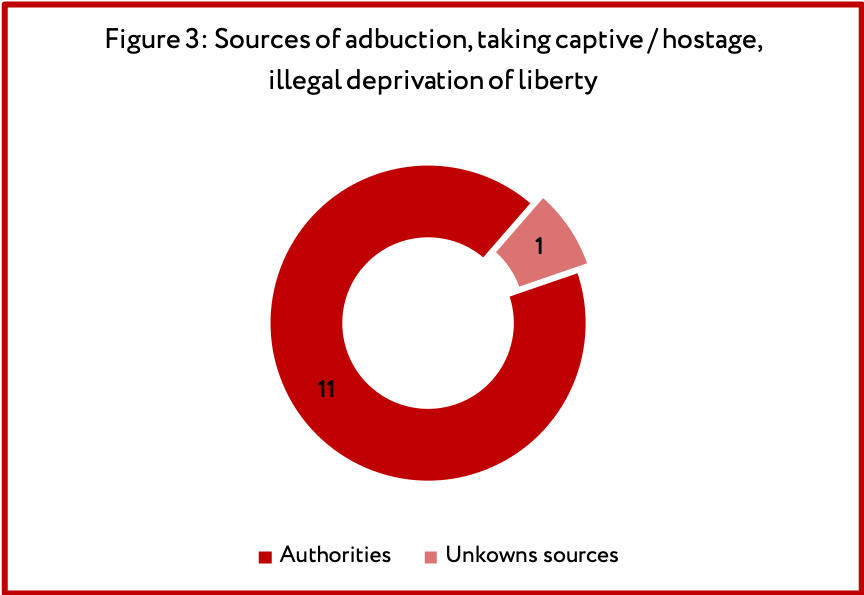

Most often, the journalists were subjected to violence during short-term detention or obstruction of their professional activity. Appearing as the main aggressors were representatives of the authorities (in 84% of the incidents), first and foremost police personnel. Thus, in Minsk on March 25, 2017, during the traditional Freedom Day opposition demonstration, 5 journalists were beaten up by security personnel, including a British journalist covering the protest action.

Most often, the victims of physical attacks became journalists working with the Belsat television channel – 15 of the 25 cases. Subjected to physical pressure five times during the period covered in this study was Konstantin Zhukovsky, a journalist from Gomel, who holds the record for the number of fines issued to him:

- In July 2017, Zhukovsky was detained short-term by employees of the traffic police (the state automobile inspectorate) when he was returning from a court where he had been covering the proceedings. The journalist was handcuffed to a tree.

- In August 2017, during a video shoot, he was sprayed in the face with an aerosol substance by a person who turned out to be a management employee of a local pig farm. Zhukovsky was hospitalised.

- In July 2018, the journalist suffered a hypertensive crisis after being detained short-term on a charge of petty hooliganism and taken to the local police station and then to court.

- In November 2018, the journalist was summoned to the military draft commissariat for a medical examination. He had already undergone a medical examination less than six months earlier but never had been subsequently called up for training.

- In January 2019, Zhukovsky was, in his words, assaulted by unidentified persons on a road in Gomel Oblast.

At the end of January 2019, Zhukovsky fled Belarus and requested political asylum in one of the countries of Western Europe.

In February 2018, the journalist Andrei Kozel, who likewise worked with the Belsat television channel and had been charged with administrative offenses on numerous occasions, was beaten up for attempting to film the vote-counting at a polling station. The journalist was brutally detained short-term and placed in detention, where he continued to get beaten up, and was subsequently charged with an administrative offence, allegedly for resisting employees of the police.

At the start of 2020, Kozel was forced to leave Belarus due to the constant pressure.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

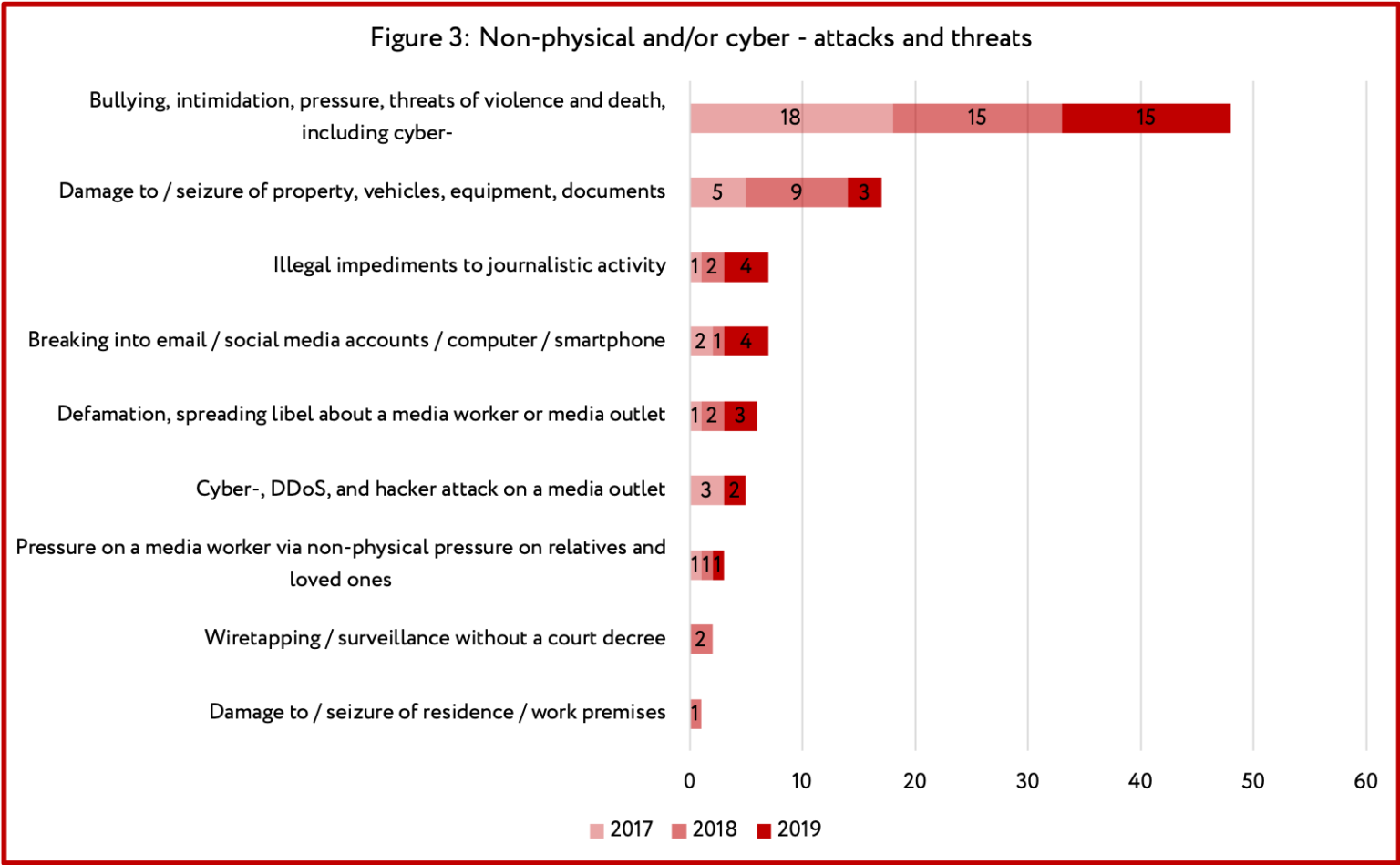

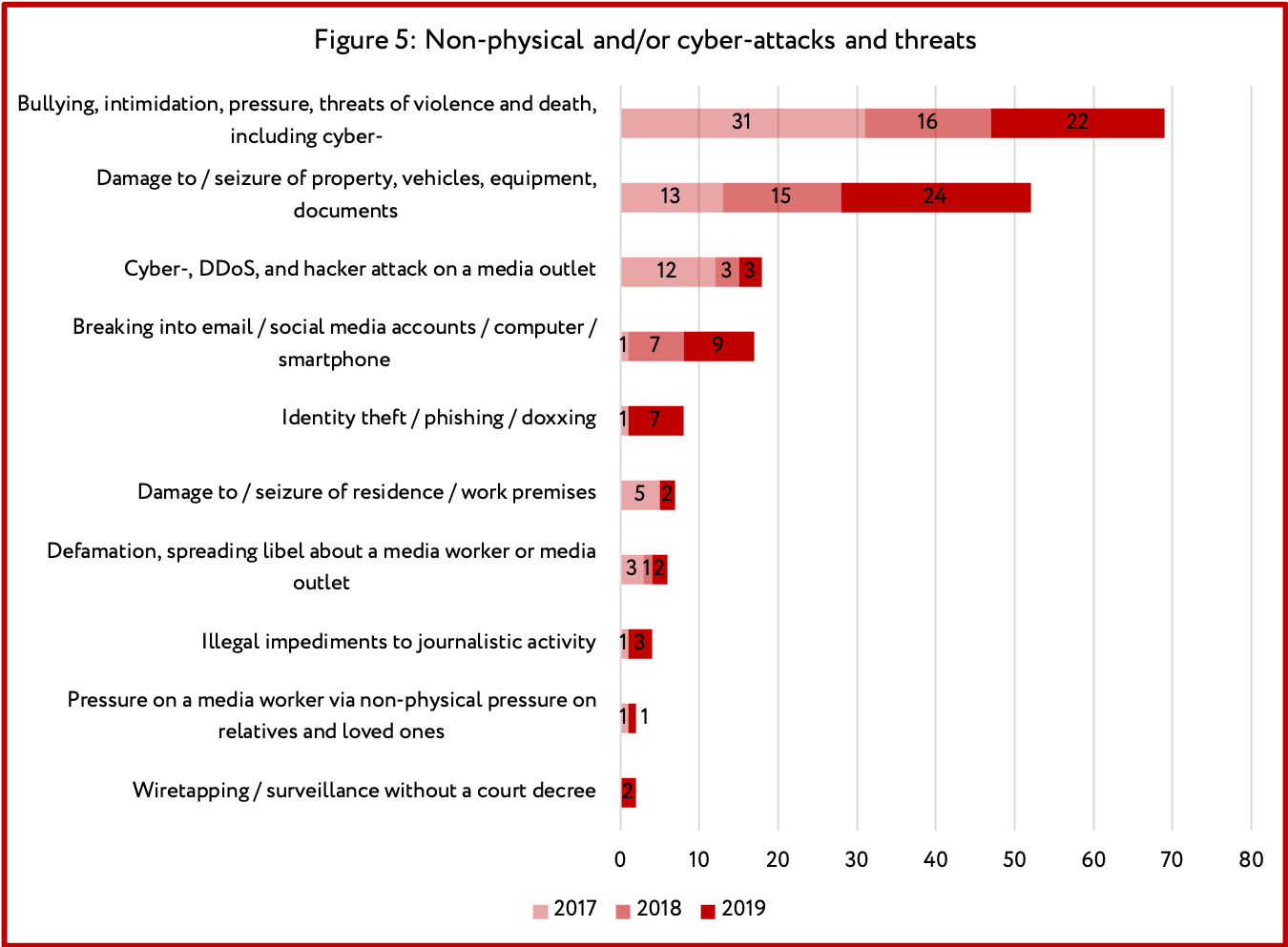

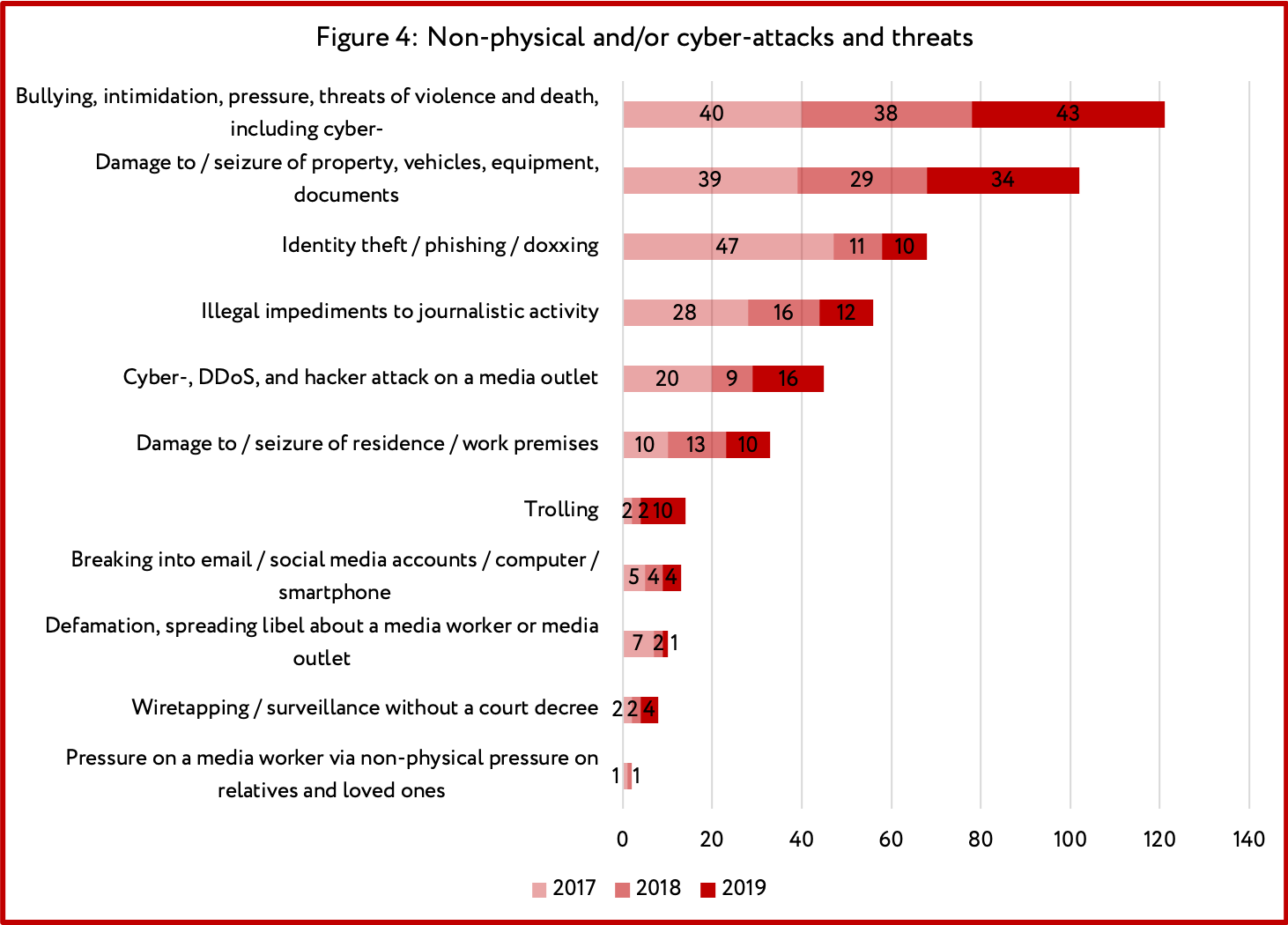

The most prevalent kinds of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats over the period covered in this study were bullying, intimidation, pressure, and threats of violence and death, including in cyberspace. They comprised more than half (48) of the total number of recorded cases (95). The second most prevalent method of non-physical pressure is damage to or seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, or documents (16). Journalists encountered the highest number of attacks of this type (9) in 2018.

In Belarus, as in Russia and the countries of Central Asia, one of the most prevalent methods of attack is pressure on a media worker by way of non-physical pressure on relatives and loved ones:

- In October 2017, the parents of Belsat journalist Alexandr Zalevsky were threatened over the phone by a stranger who identified himself as a KGB lieutenant.

- In February 2018, a search was carried out at the flat of YouTube blogger Stepan Putilo’s parents. Security personnel seized a notebook computer and a video camera. Putilo, who was studying in Poland at that moment, was inculpated under Article 368 of the Criminal Code (insulting the president).

- In September 2019, Petr Kuznetsov, founder of Gomel website Silnye Novosti [Strong News], complained that he personally and his relatives and acquaintances are constantly having problems when crossing the border.

In a number of situations, representatives of the authorities threaten journalists with taking children from the family:

- In July 2017, representatives of the authorities threatened Belsat journalists Olha Chaychits and Andrey Kozel that they would file a complaint with child protection services regarding their children.

- In April 2017, they threatened to register the family of Belsat journalist Larisa Shchiryakova as indigent and to remove the child from the family.

Cyber-attacks are a less prevalent method. During the period covered in this study, 5 cases of hacking and DDoS attacks and 7 incidents associated with breaking into social media accounts were recorded.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

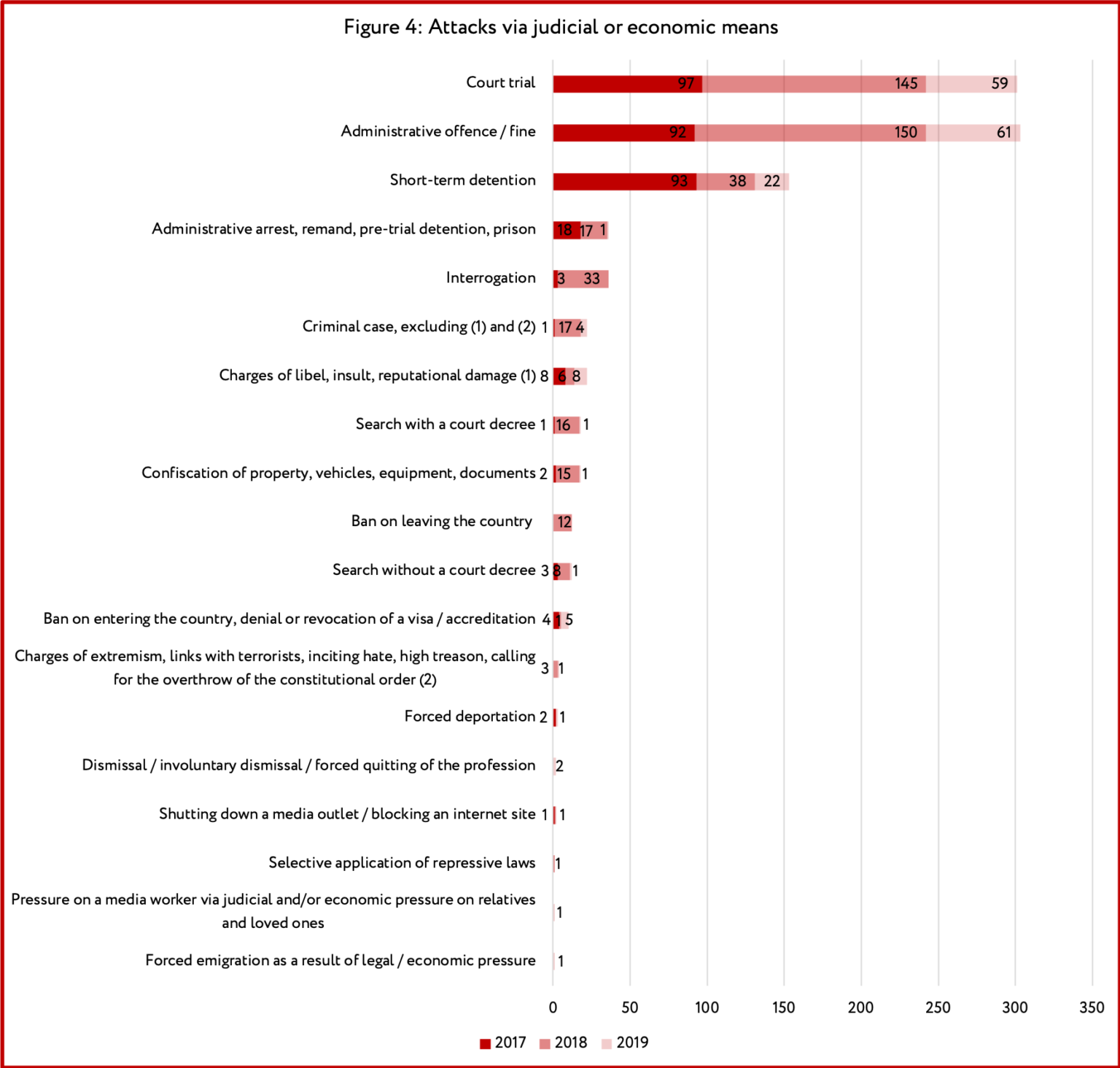

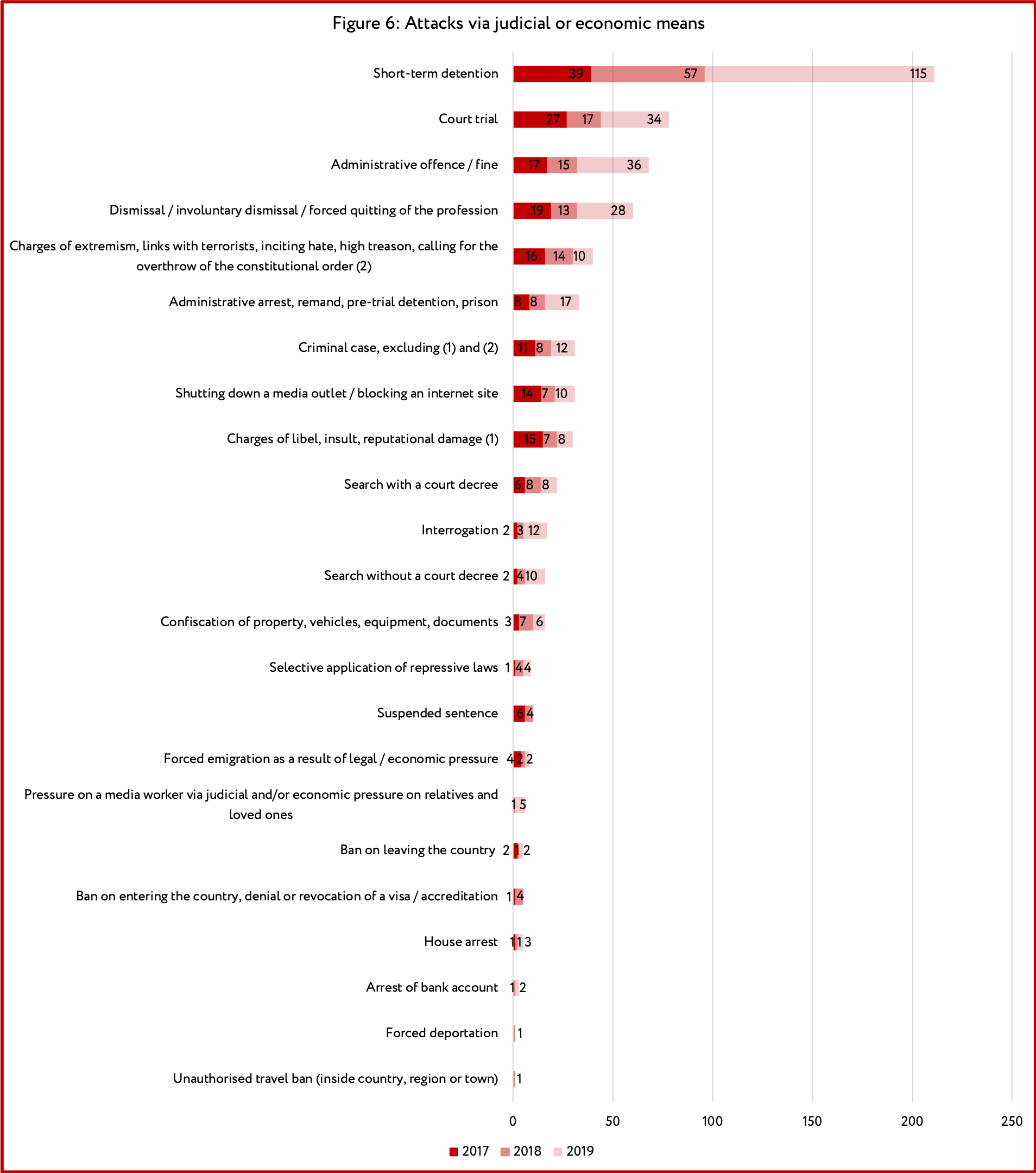

Figure 4 presents a general analysis of attacks via judicial and/or economic means. 957 attacks in this category were recorded during the period from 2017 through 2019. The top 3 methods of pressure include: administrative offences and fines; courts and court trials; and short-term detentions. In 942 out of the 957 recorded attacks in this category (i.e. 98% of the incidents), appearing as the “aggressors” were representatives of the authorities.

The most frequent reason for the attacks was the cooperation of Belarusian freelance journalists with foreign media without Foreign Ministry accreditation. Based on police reports, the courts fined journalists in accordance with Part 2 of Article 22.9 of the Code of Administrative Offences, which prescribes culpability for the illegal production and/or distribution of media output. 2018 became the “peak” year, when journalists were held administratively liable under this article no fewer than 122 times (more than in the previous four years combined). The overall sum of the fines for the year exceeded 43 thousand euros.

In most of the cases, the fines were issued to journalists working with the Belsat satellite television channel. Belsat is a part of the structure of Polish Television but positions itself as Belarus’s first independent television channel. All told, journalists and employees of the Belsat television channel were subjected to attacks via judicial and/or economic means a total of 574 times during the period covered in this study.

In March 2017 and April 2019, searches with confiscation of equipment were carried out under various pretexts in the Belsat television channel’s unregistered Minsk news office. One of the pretexts was an accusation of unauthorised use by Belsat of its name (there is a commercial enterprise of the same name operating in Belarus). Journalists were asserting that after the seizure of the equipment, police employees were affixing a Belsat sticker on their gear, which later served as grounds for its confiscation on the pretext of trademark infringement.

Criminal prosecution of journalists, media editors, and bloggers (and the searches, interrogations, and arrests associated with this) was the harshest method of pressure. Moreover, in a number of instances, the criminal cases were not formally associated with freedom of expression. The “Regnum case”, “BelTAcase”, and the criminal case against head of independent news agency BelaPAN Alexandr Lipai caused the biggest public outcry.

- The “Regnum case”: In February 2018, the Minsk City Court issued a guilty verdict in a criminal case against three Belarusian authors who had been published in Russian media: Yury Pavlovets, Dmitry Alimkin, and Sergey Shiptenko. The court found them guilty of deliberate acts aimed at inciting hate between nationalities committed by a group of individuals, and sentenced them to five years of deprivation of liberty, with the serving of the sentence delayed by three years. The convicted parties were released in the courtroom. If they do not commit violations of public order and will be carrying out the court’s directives during the three-year delayed-sentence period, the court may release them from serving their sentences. The pretext for initiating the “Regnum case” became a Ministry of Information appeal to the Investigative Committee regarding features of extremism allegedly discovered in these authors’ publications. The defendants were held in custody for 14 months – from the moment of their short-term detention in December 2016.

- The criminal case against Alexandr (Ales) Lipai: In June 2018, a criminal case was opened in relation to Alexandr Lipai, head of leading Belarusian independent news agency BelaPAN, in connection with wilful income tax evasion in a particularly large amount in the years 2016-2017. A search was conducted of Lipai’s flat; documents and professional equipment were seized. Belarusian human rights organisations claimed that there was a political undercurrent to the case and associated it with a general tendency of increasing pressure on non-state-owned media and Internet sites in Belarus. On August 23, 2018, Ales Lipai died of cancer at the age of 52. The criminal case against him was dropped following his death.

- The “BelTA case”: In August 2018, raids were carried out at the editorial offices of the BelaPAN news company, the By web portal, and several other media outlets, as well as in the flats of a number of their employees. Around 20 journalists were detained short-term and interrogated by investigators. 8 were sent to a pre-trial temporary detention “isolator” for a term of up to 72 hours. Serving as the reason for the large-scale “special op” was the unsanctioned use by some journalists of passwords to the subscription feed of the government agency BelTA’s website. It should be noted that the BelTA website materials are openly accessible free of charge and were posted by the media outlets that were now under pressure in consideration of all the rules established by BelTA. Nevertheless, criminal cases on unsanctioned access to computer information entailing the causing of significant harm were initiated in relation to 15 journalists. At the end of 2018, criminal cases in relation to 14 journalists were dropped and they were cited for administrative violations in the form of huge fines and compulsory payment of indemnification to state-owned media outlets – BelTA and the presidential administration’s newspaper SB. Belarus segodnya. The only defendant to be held criminally liable became Marina Zolotova, editor-in-chief of the internet portal Tut.By. Notably, she was charged under a different article – failure to act by an official. In March 2019, the court found Zolotova guilty and sentenced her to a fine of 7,650 Belarusian roubles (more than 3,000 euros at the National Bank exchange rate).

Among the most serious internet-related violations, the blocking of popular internet sites that cover socio-political topics ought to be pointed out. There were two such blockings, and both became high-profile. Both internet sites were accused of distributing prohibited information (including on the conducting of unsanctioned mass demonstrations). But not only were they not issued any warnings that they were breaking the law or demands to remove specific materials, they did not even know what materials specifically had served as the grounds for their being blocked in Belarus. The websites continue their activity following a change of their domain extensions:

- In December 2017, the Ministry of Information adopted a decision on restricting access to the Belorussky partizan website, the founder of which was the well-known journalist Pavel Sheremet, who had been working in Ukraine in recent years and tragically died there in 2016.

- In January 2018, access was restricted to another popular website, Khartiya 97, whose editorial staff has been working in Poland in recent years (after the criminal prosecution of editor-in-chief Natalia Radina and a number of website employees on charges of organising mass disorders following the 2010 presidential elections).

Russia

1/ KEY FINDINGS

1,116 instances of attacks/threats against professional and civilian media workers and the editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Russia were identified and analysed in the course of the study. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian and English languages using the method of content analysis. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 3.

- Russia remains a country in which the journalist’s profession is associated with elevated risks to life, health, and liberty. From 2017 through 2019, a minimum of 15 Russian media workers lost their lives, and one person has disappeared without a trace. For comparison: in the remaining 11 post-Soviet countries, the aggregate population of which is practically the same as Russia’s population, 7 media workers have died..

- The main source of attacks on journalists in Russia are representatives of the authorities – 68% of all assaults can be attributed to them.

- 63% of all attacks against journalists are carried out via judicial and economic means, above all short-term detentions, administrative and criminal cases, and involuntary dismissals.

- Monitoring of assaults on media workers works best in the capitals, which is also where the bulk of independent professional and citizen journalists are concentrated. Rapid dissemination of information on unlawful short-term detention, abduction, or other pressure on a media worker increases the likelihood of a favourable outcome.

- Russia, along with Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan, widely practices persecution of citizen and professional journalists on charges of inciting hate and defending terrorism and extremism. Among other methods of suppressing freedom of speech that unite Russia with the former republics of the USSR are punitive psychiatry (likewise used by Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) and intimidation of the relatives of journalists (as in Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan).

Taking into account the situation with freedom of the mass media, which is getting worse with each passing year, as well as the peculiarities of the practices in some regions, it can be said with confidence that many threats and attacks of various types never do become public knowledge. Journalists have become accustomed to writing about others and are not always prepared to “make news” themselves and become the central protagonists of publications.

With rare exceptions, assaults on media workers in Russia remain uninvestigated, while the perpetrators do not receive lawful punishment. In this situation, monitoring and analysis of attacks and threats to journalists are particularly important, inasmuch as this work allows the most common risks to be identified and managed.

Besides that, verbal bullying, threats, cyber-attacks, and breaking into social network pages and emails are regarded by the majority of journalists working in Russia as an unavoidable part of everyday professional activity. Such incidents are rarely made public- this explains why they comprise a relatively low percentage of recorded attacks.

2/ THE MEDIA IN RUSSIA

In the 2020 edition of the annual World Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders, Russia occupies 149th place out of 180.

According to the Freedom of the Net report for 2019 compiled by Freedom House, Russia lacks freedom of the internet (31 points out of 100). This indicator places Russia in the same group of countries as China, Saudi Arabia, and Cuba.

Foreign individuals and legal entities are prohibited from owning more than 20% of any one publication in Russia.

TOTAL NUMBER OF MEDIA OUTLETS AND AUDIENCE SHARE

According to the data of the Federal Service for Supervision in the Sphere of Telecom, Information Technologies, and Mass Communications [Roskomnadzor], as of December 31, 2019 the total number of registered media outlets comprises 65,849, of which 42,882 are print, 21,770 are electronic, and 1,197 are news agencies. In just 2019 alone, 1,894 print media outlets, 2,012electronic media outlets, and 80 news agencies were registered. According to Roskomnadzor’s data, the number of newspapers and magazines in Russia fell from 2009 to 2019 by approximately 40%, which is the highest indicator in the past 10 years. In just 2019 alone, 7,498 registration entries were removed from the media register.

According to the data of the Levada-Center’s annual report on the media landscape in Russia in 2019, television remains the main source of news for 73% of the population. Moreover, trust in this source over 10 years has fallen from 80% to 52%. 39% of those surveyed get their news from internet publications and social networks. The audience for radio and newspapers over 10 years has shrunk by more than half – a mere 15% of Russians use them to get news.

The leading TV channels as of the end of 2019 remain Rossiya 1, Perviy kanal [First Channel], and NTV. The major broadcast grid does not include a single channel that would offer independent, objective news. The only such channel is Rain, which is accessible on the internet and has only a 1% audience share.

STATE MEDIA

The main sources of funding of the state media are the state, AO Natsionalnaya Media Gruppa, and Gazprom-Media.

- Perviy kanal is owned by the Federal Agency for State Property Management [Rosimushchestvo] (38.9%), AO Natsionalnaya Media Gruppa (29%), VTB Capital (20%), TASS (9.1%), and Ostankino (3%).

- The founder of the private media holding company Natsionalnaya Media Gruppa is the Russian billionaire and owner of Severstal, Alexey Mordashov. Among Natsionalnaya Media Gruppa’s media assets are Perviy kanal, REN TV, STS, Pyatiy kanal [Fifth Channel], Telekanal 78, the newspaper Izvestiya, and others.

- Gazprom-Media belongs to Gazprombank and owns the NTV, TNT, TV3, and Pyatnitsa [Friday] television channels and a multitude of other entertainment channels, magazines, internet sites, and radio stations, including Ekho Moskvy. The director-general of the Gazprom-Media holding company is ex head of the Federal Service for Supervision in the Sphere of Telecom, Information Technologies, and Mass Communications [Roskomnadzor] Alexandr Zharov.

- The All-Russian State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company (VGTRK) was founded by the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR in 1990. The corporation includes the Rossiya 1, Rossiya 2, and Rossiya 24 channels and others.

- The most popular channel abroad is Russia Today, financed out of the Russian Federation budget. Information was published in April 2020 about how Russia Today had spent 22.3 billion roubles received from the federal budget in 2019.

INDEPENDENT MEDIA

Despite the fact that independent media lag far behind state media in terms of audience size, they are often the most heavily cited in social media (number of links in social networks). According to the data of the Medialogiyamedia monitoring and analysis service (63% owned by VTB bank), as of January 2020:

- The top five most cited newspapers include Novaya gazeta (4th place).

- Three of the most cited television channels includes Rain, which holds second place (536,125 hyperlinks in the social networks).

- Among the most cited radio stations, Radio Liberty holds first place; Ekho Moskvy is second.

- In the citations rating for internet sites, the Meduza portal holds second place, and MBK media.

MEDIA LEGISLATION

“Lugovoy’s law”, adopted in 2014, allows Roskomnadzor, upon the instruction of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the RF, to summarily block websites that are allegedly disseminating calls for mass disorders and extremist information without a court ruling.

- In 2014, the opposition media websites ru, Kasparov.ru, and Yezhednevniy zhurnal were blocked.

- According to the Internet Trends 2019 report, in 2018, access to nearly 650 thousand websites was prohibited in Russia – five times more than a year earlier.

- In 2019, the international human rights group Agora and the civic organisation Roskomsvoboda recorded438,981 instances of interference with freedom of the internet in Russia, of which 434,275 were associated with restricting access to internet sites and services, as well as with bans on various kinds of news.

According to the Law on the Mass Information Media, as of January 1, 2016, the stake of foreign shareholders in the charter capital of Russian mass information media shall be limited 20%, foreigners and dual citizens shall be prohibited from appearing as founders of mass information media in the RF. According to the amendments to this law adopted in December 2019, NGOs, mass information media, and individuals may be recognised as foreign mass information media carrying out the functions of a foreign agent.

“Yarova’s law”, adopted in 2016, stiffens the punishment for terrorism and extremism and obligates operators to hold on to personal data, including voice calls and written correspondence (photo, audio, voice messages) for 6 months and to furnish them if necessary to the special services. Likewise, the law obligates organisers of the dissemination of information on the internet (messaging services, social networks, and other services) to decode users’ messages upon the demand of the FSB and to furnish keys to encrypted traffic. In April 2018, a series of unsuccessful attempts to block the Telegram social network was undertaken under this law. On June 18, 2020, a decision was adopted to unblock Telegram.

On March 29, 2019, a law entered into force prohibiting the dissemination of fake news and the insulting of representatives of the authorities in the media and internet. The Law on Fake News is being actively used by the authorities against journalists in the period of coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Besides that, as of April 1, Article 207.1 “Public dissemination of knowingly false information about circumstances representing a threat to the life and safety of citizens” appeared in the Criminal Code. It too is widely used against media workers covering the topic of the pandemic in Russia.

In November 2019, a law on the “sovereign internet”, adopted by the State Duma, entered into force, prescribing the creation of a national internet traffic routing system. Besides this, it allows Roskomnadzor to take providers’ channels under control and block websites by itself.

At the end of 2019, a law was signed that allows “foreign agent mass information media” to be fined in a sum of up to 5 million roubles, as well as for individuals to be arrested for the creation or dissemination of the publication of such mass information media for a term of up to 15 days.

In February 2020, the register of mass information media carrying out the functions of a “foreign agent” includes 12 media portals, including Voice of America, Nastoyashcheye vremya, and Radio Liberty and its subdivisions.

In January 2020, the Ministry of Justice likewise proposed introducing an amendment to the Code of Administrative Offences under which it will be possible to issue fines for dissemination of the materials of publications not registered in Russia as mass information media (including foreign ones), as well as for reposts of their publications.

On July 11, 2020, for the first time, a Russian journalist was issued a warning on account of cooperation with foreign media outlets – the Polish channel Belsat – without Foreign Ministry accreditation. This journalist became Roman Yanchenko, a resident of the city of Kemerovo. Such a practice, particularly against journalists working with the Belsat television channel, is widespread in neighbouring Belarus.

In moments of political flare-ups, the authorities restrict the population’s access to the internet. The most recent examples:

- rallies in Ingushetia against the transfer of a part of the Republic’s territory to Chechnya in the autumn of 2018 and the spring of 2019;

- protest actions in Moscow in the summer of 2019;

- rallies demanding repeal of the results of the mayoral election in the capital of Buryatia in September 2019;

- protests against the construction of a rubbish tip (dump) in Shiyes (Arkhangelsk Oblast) in October 2019.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

The job of a Russian journalist is associated with elevated risks to life, health, and liberty: 1,116 assaults on journalists have been recorded over the three years being analyzed in this study. One fifth of all the attacks (225 incidents) fall into the category of physical assaults. A minimum of 15 Russian media workers have lost their lives in these three years. In 2019, the number of physical assaults on journalists increased by a quarter compared to 2017.

The bulk (63%) of all attacks against journalists in Russia consists of attack via judicial and economic means, above all short-term detentions at mass demonstrations, as well as the initiation of criminal and administrative cases against professional and citizen media workers. In 2019, the number of attacks of this type increased by 67% compared to 2017.

Bullying, intimidation, and threats of reprisals lead the way among the sub-types of non-physical attacks. Coming up behind them are damage to and seizure of vehicles, equipment, and documents. Cyber-, DDoS, and hacker attacks round out the first three attacks and threats of a non-physical nature. As is the case in the other post-Soviet regions in this study, journalists regard threats and attacks of a non-physical nature as a commonplace component of their everyday work and do not make these incidents public.

In 68% of the cases, the source of the attacks on journalists are representatives of the authorities, first and foremost the police. Short-term detention and arrest are far from the only ways of exerting influence that the authorities have in their arsenal. Often, the assaults are of a comprehensive, or “package”, nature: a journalist is detained short-term, beaten, and subjected to interrogation and search, and pressure is exerted on his or her loved ones, after which an administrative or criminal case is initiated, and the journalist is tried and convicted and sentenced to deprivation of liberty.

The most dangerous Russian region for a journalist is Moscow, where one third of all the recorded attacks on media workers took place. The risk of being attacked in the capital is 2.95 compared to 0.77 for Russia as a whole (the risk index calculated based on the number of attacks per 100 thousand people). The number of attacks in regions of elevated risk for media workers looks as follows:

- Moscow – 369

- Saint Petersburg – 85

- Sverdlovsk Oblast – 50

- Krasnodar Kray – 45

- Moscow Oblast – 44

- Republic of Ingushetia – 24

- Republic of Daghestan – 22

Only some examples of the most prevalent sub-categories of attacks on media workers are cited in the report. More detailed information with respect to each incident of assault can be found on the Media Risk Map on the Justice for Journalists Foundation website.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

DEATHS

For Russian media workers, the risk of losing one’s life remains very high. During the period studied, a minimum of 15 journalists lost their lives as the result of murders, beatings, suicides, and accidents. The cause of death often remains unestablished, and the circumstances surrounding the death are not investigated, while the criminal cases are closed for lack of evidence or for other reasons.

- On March 16, 2017, 35-year-old journalist Yevgeny Khamaganov, editor of the AsiaRussiaDaily website and the founder of the SNB [Site of the Buryat People] internet portal, died in a hospital in Ulan-Ude. According to official data, the journalist died in intensive care as a result of a diabetic coma. Khamaganov’s friends, who were not aware that he had diabetes, suspect that the reason for the journalist’s death could have been yet another assault on him. The previous assault on the journalist was committed in June 2015, when Khamaganov’s head was smashed and his neck vertebrae fractured.

- On April 19, 2017, 73-year-old Nikolai Andrushchenko, author for the newspaper Noviy Peterburg [New Petersburg], died in Saint Petersburg’s Mariinsky Hospital. He had been brought there on March 9 with a severe head injury. The journalist, who had been working on anti-corruption investigations, died a few weeks later without ever regaining consciousness.

- On April 14, 2018, Maxim Borodin, an investigative journalist who wrote about hot-button issues, died in Yekaterinburg. He fell out of the window of his fifth-floor flat; three days later he died without regaining consciousness. The previous assault on Borodin had been committed on November 10, 2017: unknown assailants had hit him on the head with an iron pipe after the journalist had given an interview to the Raintelevision channel about his investigation in relation to admirers of the emperor Nicholas II and Natalia Poklonskaya called “The Sect of the Tsar-Deifiers”.

- On July 30, 2018, cameraman Kirill Radchenko, director Alexandr Rastorguyev, and war correspondent Orkhan Dzhemal, who were investigating the activities of the Wagner Group in the Central African Republic, were murdered in that country. This crime is yet to be solved, and those responsible have not been located. Data from independent investigative journalism conducted by the Dossier Center and Project was ignored by the official investigation.

- On July 13, 2019, the body of a well-known television cameraman, 55-year-old Pyotr Mikov, who worked with LenTV, 100 TV, and «78», as well as in the socio-political show Open Studio, was found on Vasilyevsky Island in St. Petersburg. The victim’s head had been shot through. Found next to the body was a shell casing from a pistol which, according to the investigation data, was not related to the murder.

- On July 17, 2019, 35-year-old local journalist, blogger, director of the Gorizont (Horizon) political-information technology agency, and author of the Telegram channel “Komitet” Mikhail Kurakin died in Togliatti (Samara Oblast). The day before his death, he wrote in Facebook: “I don’t know why, but it seems that I’ve got serious problems”. A criminal case was initiated in connection with his death under the “incitement to suicide” article of the Criminal Code; it was closed in half a year for the reason of the impossibility of identifying the person who had incited the person to kill himself.

- The editor of the independent online newspaper Volgogradsky reporter, 35-year-old Leonid Makhinya, disappeared without a trace in June 2018. Searches conducted by the police, volunteers and the journalist’s relatives and friends have yet to yield any results. A murder criminal case has been opened in connection with his disappearance.

ATTEMPTED MURDERS

13 attempted murders were recorded during the period studied, including:

- On February 2, 2017, television journalist and coordinator of the Open Russia movement Vladimir Kara-Murza, Jr. was hospitalised in Moscow with symptoms of poisoning. This was the second attempt to poison Kara-Murza, the first having been in 2015. In both cases he was diagnosed with a “toxic effect from an unidentified substance”.

- On October 23, 2017, Ekho Moskvy presenter Tatiana Felgenhauer was assaulted at her workplace. The offender, later declared mentally incompetent, broke into the radio station building and wounded the journalist in the throat with a knife.

- On December 21, 2017, Caucasian Knot journalist Vyacheslav Prudnikov was wounded by gunfire in an armed attack in Rostov Oblast. Prudnikov links the attack with his professional activities at Caucasian Knot: “I got my camera out to take some pictures. Suddenly a grey imported car pulled up. A young person jumped out of it, demanding that I tell him what I was doing. A conflict arose, the man was trying to hit me, and after that he pulled out a pistol.”

- On September 11, 2018, Pussy Riot participant and Mediazona publisher Pyotr Verzilov was admitted to a Moscow hospital in a critical condition after being poisoned. He was working on investigating the deaths of Russian journalists in the CAR.

- On March 14, 2019, a felonious attempt with the use of a firearm was committed against coordinator of the netproject Boris Ushakov in the city of Vladimir. Ushakov had earlier on numerous occasions exposed sadists, and had at a press conference recounted the details of a number of reprisals against prisoners in institutions of the Federal Penitentiary Service [FSIN] Administration for Vladimir Oblast.

- On June 1, 2019, Krasnodar blogger Vadim Kharchenko suffered three gunshot wounds and two knife wounds, as well as head injuries, in the course of a rendezvous with a source. The day before, an unknown person had scheduled a meeting for him and had promised to hand over evidence of how his colleagues in one of the city’s Interior Ministry police stations are falsifying narcotics trafficking criminal cases, beating short-term detainees, and planting prohibited substances on them.

- On December 8, 2019, in Chelyabinsk, production editor of the Obshchestveniy zashchitnik [Public Defender] newspaper and website Yulia Zyabrina was shot in the head in the yard of her house – in her words, from an air gun. Earlier, the newspaper where she works had been receiving threats from unknown persons with promises to “take care of things”. Police refused to initiate a criminal case in connection with the journalist’s statement about her attempted murder. Sources in the Interior Ministry’s Main Administration for Chelyabinsk Oblast were later asserting that the story about the attempted murder had been made up.

ABDUCTION, TAKING CAPTIVITY/HOSTAGE, ILLEGAL DEPRIVATION OF LIBERTY

As paradoxical as this may sound, journalists are illegally deprived of liberty and abducted by employees of law enforcement agencies and special services. Such incidents have been recorded during the period examined in the study in Moscow, Solnechnogorsk, Volgograd, Tomsk, Nazran and Grozny.

- On January 4, 2018, Vladimir Arsentiev, an author for the newspaper of regional human rights organisations Za prava cheloveka [For Human Rights], was stopped by highway police employees, who called a tow truck, took the keys to his car, and drove the journalist himself off to a police station. He was only released 48 hours later.

Often, the illegal deprivation of liberty of media workers is a part of “package attacks” on journalists, which lead to their arrest, conviction, and long imprisonment. In a number of cases, these attacks are associated with torture and a whole range of flagrant violations of journalists’ rights and Russian Federation laws.

- On June 23, 2017, the host of a YouTube channel about NGOs, Alexandr Batmanov, was forcibly brought in “for a talk” to the Sovietsky Rayon police station in Volgograd. The police spoke with him and were about to let him go, but after some kind of discussions with the prosecutor’s office they decided to “leave it till Monday.” Batmanov was locked up in one of the police station offices without food or water on Saturday and Sunday. Attempting to escape, he fell from the third floor and shattered both heels. He was then arrested, operated on in a prison hospital, officially charged, and tried. The court found him guilty of stealing a sausage and sentenced him to 2 years and 1 month in a strict-regime prison colony.

- On May 3, 2018, employees from the «Е» Centre for Combating Extremism detained activist and blogger Maxim Shulgin short-term in the Levyi Blok [Left Bloc] civic movement’s office in Tomsk. On the way to the «E» centre, they laid him face down on the floor between the car seats, put their feet on top of him, and switched on the heater. This resulted in first- and second-degree burns. On December 27, Shulgin was abducted, this time by people in masks who identified themselves as FSB employees, who tied him up with tape and were asphyxiating him with a plastic bag and threatening to kill him, compelling him to retract previously given testimony against security personnel.

- On November 1, 2019, Islam Nukhanov, who has diminished hearing and vision, was abducted in Grozny for a video posted by him on the YouTube video hosting platform entitled “How Kadyrov and his associates live. Part 1.” Nukhanov had filmed fences and palaces in the centre of Grozny with a car’s dashboard camera. In prison, the vlogger,who at 27 years of age weighs barely over 50 kg, was subjected to beatings and torture. Officially, Nukhanov is charged with illegal possession of a weapon and the use of violence against a policeman.

NON-FATAL ATTACKS/ BEATINGS / INJURIES/ TORTURE

Beatings continue to remain the most prevalent way of exerting influencing on journalists, with 179 incidents recorded in three years. The attacks of this category are conducted not only by authorities, but also by others as well.

Journalists are exposed to the greatest risk of physical attack from the police, special forces [OMON], and Federal Penitentiary Service [FSIN] employees in the course of:

- work covering protest actions

- in pre-trial detention

A number of examples are given in the Attacks via judicial and/or economic means section.

Media workers are likewise regularly subjected to physical assaults by unknown perpetrators who are not representatives of the authorities, for example security guards, vendors, business owners, and simply aggressive groups of inebriated people. As a rule, this happens when the journalists are trying to film stories about conflict situations in shopping centres, restaurants, shops, and medical clinics, and at railway stations and construction sites. Often, the subjects of the news stories themselves physically impede the carrying out ofeditorial tasks by the journalists: they take away microphones, smash cameras, and either threaten or commit violence. Further examples are given in the Non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats section.

- On July 27, 2017, the editor of the Lichnoye mnenie [Personal Opinion] website, Anver Yumagulov, was assaulted in Ufa. A thick-set 35-40 year old man approached him asking for help pushing his car. On the way to the vehicle, he assaulted the journalist. At the hospital to which the victim was taken, he was diagnosed with broken ribs, nose, and jaw.

- On November 21, 2017 in Lipetsk, hooligans assaulted journalists from the Lipetskoye Vremya [Lipetsk Time] television channel. The incident took place in the Moskva shopping centre, whilst the television crew were filming scenes for the morning programme. Two drunk patrons did not like the filming and assaulted the journalists. Correspondent Anton Palchikov was hit in the face; cameraman Valery Faustov was diagnosed with a facial bone fracture.

- On March 18, 2018 in Makhachkala, RIA Derbent journalist Malik Butayev, who was covering the elections, was assaulted by Mahomed Mahomedrasulov, an employee of the Lenin Rayon Administration. Butayev was not only performing his professional activities, he was also registered as a member of the electoral commission with advisory voting rights.

- On March 18, 2018, in the village of Duvanovka in Omsk Oblast, the head of a precinct electoral commission, Yuri Borzilo, refused entry into the polling station to Natalia Yakovleva, a journalist from the publication V Omske [In Omsk], and her colleague from the newspaper Chetverg [Thursday], Irina Krayevskaya. Later, when the journalists started talking to people, Borzilo ran up and started threatening them: “If you want to leave here alive get rid of the camera!” After this he hit the journalist in the head.

- On May 25, 2019, the head of Shirinsky Rayon in Khakassia, Sergei Zaitsev, assaulted Ivan Litomin, a correspondent for the Rossiya 24 television channel. Zaitsev was speaking to the camera crew in a raised voice, and then, having attempted to rip the microphone from Litomin’s hands, he grabbed him and threw him roughly to the ground shouting “I told you to get out of here”.

- On April 26, 2019, Valentin Gorshenin, a journalist for the REN TV television channel, was at the scene of a breaking news incident in Shchelkovo in Moscow Oblast: a man had barricaded himself in a high-rise building and was threatening to blow it up. A medical worker with the psychiatric aid team demanded that the journalist identify himself and show his accreditation. In the end, the medical worker took away the documents from the correspondent, beat him up, and smashed a professional camera worth 350 thousand roubles [around 5,000 US dollars].

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

Verbal bullying, seizure of property, damage to equipment, cyber-attacks, and breaking into social network accounts and emails are perceived by the majority of journalists working in Russia as an unavoidable part of their everyday professional activity. Such incidents are rarely made public – this explains their relatively low percentage among recorded attacks.

BULLYING, INTIMIDATION, PRESSURE, THREATS OF VIOLENCE AND DEATH

Media workers regularly receive both personal threats of violence and death and threatening text messages by telephone and through the internet. Verbal warnings are regularly followed by real physical assaults.

- In August 2017, the Krasnodar journalist Andrey Koshik received a number of telephone and text-message threats with a demand to “cease writing about Rostov.” Text messages with foul language, containing threats of physical reprisals and insults, were being received from a number that the journalist did not recognise. One of the people threatening Koshik by telephone identified himself as an agent of Rostov’s Centre for Combating Extremism.

- On November 5, 2017, after the short-term detention of Gradus TV correspondent Vladimir Putilin in Moscow for violating the procedure for holding a demonstration and his subsequent interrogation, someone in a separate office, who identified himself as an employee of the «E» Centre, was threatening the journalist with a criminal case under the “extremist” article of the Criminal Code. After this, Putilin began receiving threats from people wearing civilian clothing. And three days after he had refused to talk to them, he regained consciousness in hospital with serious injuries and loss of memory. “At the police, they said that I had fallen from a platform. If I had merely fallen, I would hardly have gotten such injuries, on all sides of the body. I’ve got bruises on the arms, my back is all lacerated, my head is smashed, and my thigh bone is broken…”

- On February 5, 2018 in Yekaterinburg, Alexey Kuznetsov, the host of a YouTube channel dedicated to the problem of torture in Russian prison colonies, reported about threats that had been addressed to him. Upon returning home, he had discovered a note that demanded in crude language that he delete a video and “start minding your own business”. “You have children too, take care of your family and your daughter”, the note stated.

- On June 25, 2018, Rostov journalist Anna Lebedeva pulled the latest of many anonymous letters from her post box, this one containing threats of physical reprisal: “You filthy scum and viper you better keep your eyes open before a brick falls on your head” [punctuation sic].

- On March 16, 2019, the speaker of the Chechen parliament, Mahomed Daudov (aka ‘Lord’), recorded a video message addressed to the Chechen blogger Tumso Abdurakhmanov, in which he announced a blood vendetta against him. Daudov’s reaction came after the blogger had called Akhmat Kadyrov a traitor to the Chechen people.

- In August 2019, Vitaly Bespalov, editor-in-chief of the Parni PLUS website in St. Petersburg, received an emailed letter with threats signed by the homophobic group Pila against LGBT. He was given an ultimatum in the text: kill photographer Maxim Lapunov, who had reported on torture in a “secret prison for gays” in Chechnya, before October 1, 2019. The anonymous authors of the letter otherwise threatened reprisal against Vitaly himself by the end of the year.

DAMAGE TO/SEIZURE OF PROPERTY, VEHICLES, EQUIPMENT, DOCUMENTS

Such attacks on media workers mostly occur concurrently with beatings of journalists in the course of their work on news stories. As a rule, the attackers try to break audio and video recording equipment and/or a telephone and to take away documents. Media workers’ means of transportation are regularly damaged as well.

- On June 12, 2017, during an anti-corruption rally by supporters of Alexei Navalny in Moscow, a man assaulted Caucasian Knot correspondent Patimat Mahmudova and broke her video camera.

- On December 17, 2017, RIA Daghestan special correspondent Jemal Aliyev was beaten in Moscow. The moment of the attack was captured on street CCTV security cameras. Aliyev was hit on the head several times and his bag, documents, and iPhone 7 were taken.

- On February 7, 2018, in Moscow, unknown persons assaulted the presenter of the Che channel’s television programme Reshala, Vladislav Chizhov, severely beating him. The assailants knocked the journalist to the ground and hit him several times. One of the malefactors came up to Chizhov’s car and smashed the windscreen.

- On May 5, 2018, at the “He’s not our tsar” demonstration in Moscow, a Federal National Guard Troops Service member hit Vedomosti photographer Yevgeny Razumny with a baton and smashed his camera lens. The journalist was detained short-term but released after a while.

- On February 18, 2019, in Irkutsk, a cameraman for the Vesti-Irkutsk programme, Roman Vasyokhin, had his camera smashed, while correspondent Anastasia Tsygankova was grabbed and pushed down a staircase. This happened during the filming of a story about an encounter between disgruntled customers and representatives of the consumer lending co-operative Zolotoy Fond [Golden Fund].

- On June 11, 2019, in Perm, during filming of a story about a trial in a case about the illegal demolition of garages, a security guard tore a microphone from the hands of correspondent Larissa Strelnikova, ripped off its foam windscreen, and threw it away over a fence. On the footage shot by the television channel, a man in uniform can be seen pushing the journalist and hitting her in the face as she tries to shield herself with a microphone.

CYBER-, DDOS, AND HACKER ATTACKS AND BREAKING INTO SOCIAL NETWORK PAGES

As a rule, identifying the source of the threats in attacks of this kind is not a simple matter. Assaulters can be tracked down indirectly by cross-referencing the attacks with the publication of investigative materials or with an increase in opposition activity.

- In August 2018, seven journalists taking part in the work on the Moloko plus almanac noticed attempts to break into their Facebook and email accounts after an incident involving an assault and a visit by the police to a demonstrations against the construction of a church in a public garden in Yekaterinburg reported attempts to break into their Telegram accounts.

- In the summer of 2019, the anonymous Telegram channel “Tovarishch Mayor” [“Comrade Major”] published the personal data of approximately three thousand people, including those detained short-term at protest actions in Moscow on July 27 and August 3. The database has the passport data and telephone numbers of four Mediazonajournalists -the police had written down the passport data of three of them before the August 3 demonstration. Also on the list are journalists from Radio Liberty and correspondents from Meduza, MBK media, Takiye dela, The Village, and Rain. Some of these were detained short-term during the protest actions at the beginning of June in connection with the case of journalist Ivan Golunov.

- In October 2019, journalists from the publication Proyekt [Project] faced threats after they had begun working on articles about the activities of Russian mercenaries and political operatives in Africa and the Near East who were allegedly associated with businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin. The journalists were receiving “obscene, coarse, and unpleasant” threats of physical reprisals via email, asserts Proyekt’s editor-in-chief Roman Attempts were also made to break into their Facebook, Telegram, and Google accounts.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

The predominant method of pressure on the media in Russia (63%) are attacks via judicial and economic means. In 2019, the number of attacks of this type increased compared to 2017 due to an increase in the number of journalists detained short-term at protest actions, and comprised 324 incidents.

The principal source of attacks on journalists are representatives of the authorities, first and foremost police, who account for 68% of all assaults. During the period covered in this study, 211 instances of short-term detention of journalists without subsequent arrest were recorded, as were 33 arrests in criminal cases and administrative arrests, 5 instances of house arrest, and 5 bans on leaving the country.

Violence is regularly used during short-term detentions, arrests, searches, interrogations, and other procedural actions in relation to media workers, while their rights to protection and a fair trial are violated.

SHORT-TERM DETENTIONS

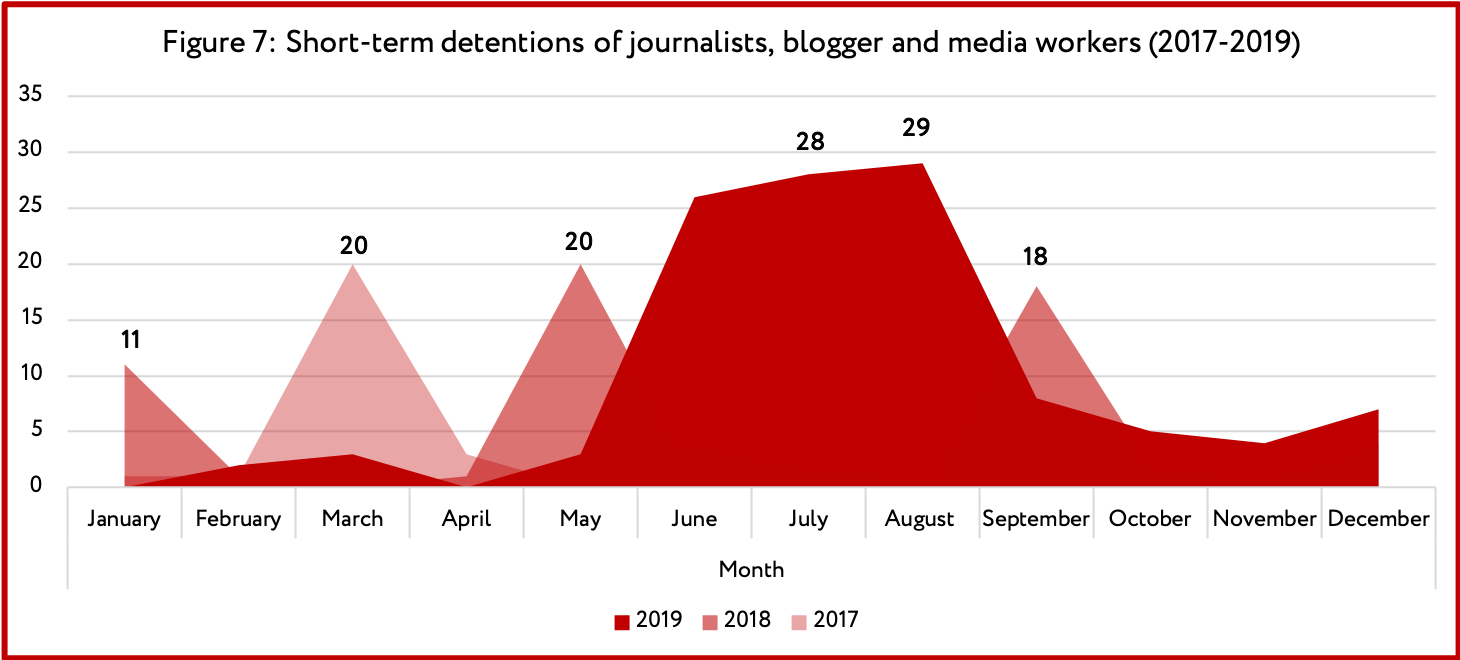

The number of media workers detained short-term increased fourfold in 2019 compared to 2017. This dynamic correlates with an increase in protest sentiments and an intensification of repressions by the authorities against journalists covering mass protests. The main high points of short-term detentions can be seen in Figure 7.

- On March 26, 2017, journalists covering anti-corruption protests in Russia were detained short-term in Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and Makhachkala.

- On May 5, 2018, the mass action “He’s not our tsar” was taking place, at which journalists were detained short-term in Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Yakutsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Chelyabinsk.

- On September 9, 2018, a demonstration against an increase in the pension age took place, at which journalists were subjected to short-term detentions, while some were beaten up.

- On June 7, 2019, solitary pickets took place in support of journalist Ivan Golunov of the publication Meduza.

- From July 27 to August 10, 2019, a series of demonstrations took place in Russia’s cities under the slogan “Let’s bring back our right to elections” and for the release of activists detained short-term in the “mass unrests” case: besides the actual demonstration participants, the police were detaining short-term and beating up representatives of the press.

ARRESTS, TRIALS, AND CRIMINAL CASES

The number of journalists placed in custody doubled in 2019 compared to 2017. Criminal cases against journalists are most often started up under one or several Criminal Code articles:

- extremism; links with terrorists; inciting hate (40 instances)

- libel, defamation, reputational damage (30 instances)

- extortion, embezzlement, fraud, possession of firearms, dealing narcotics (31 instances)

The case of Ivan Golunov, who was detained short-term on June 6, 2016 in the centre of Moscow, allowed the mechanisms of how evidence is falsified to be revealed, and likewise became one of the most vivid manifestations of “workplace solidarity”, thanks to which he was ultimately released. The special correspondent for the internet publication Meduza was detained short-term by several operatives who”discovered” a bundle with a narcotic substance in his backpack whilst searching him. Later, yet another bundle was seized during a search in Golunov’s flat. The journalist was charged with the illegal production, sale, or transportation of narcotic agents, psychotropic substances, or analogues thereof. Golunov was declaring that the narcotics had been planted on him, and that a video filmed in an underground narcotics laboratory had nothing to do with him. The investigator asked for Golunov to be sent to a pre-trial temporary detention “isolator” for two months; however, as a result of unprecedented public pressure, the Nikulinsky District Court of Moscow placed him under house arrest. Already on June 11, the criminal prosecution of the journalist was withdrawn, while a criminal case was initiated on charges of exceeding official authority in relation to the Interior Ministry employees who had been involved in Golunov’s case.

THE GOLUNOV EFFECT

It is noteworthy that within a few weeks of Ivan Golunov’s transfer to house arrest and the dropping of fabricated charges against him, several media workers in other regions were released from prisons or transferred to house arrest. Their lawyers and loved ones, astounded by such “humanity” from authorities, referred to it as the “Golunov effect”:

- On June 7, 2019, in Kabardino-Balkaria, police detained the activist, freelance journalist, and founder and chairman of the Circassian civic organisation Habze Martin Kochesoko short-term. Interior Ministry employees were asserting that they had found marijuana in his car. Kochesoko was taken to a police station, and after that to a pre-trial temporary detention “isolator” in Nalchik, where, under pressure from security personnel, he gave confessionary testimony. On June 13, the journalist was transferred from the “isolator” to house arrest. On August 23, he was released.

- On June 17, 2019, Igor Rudnikov, editor and publisher of the Kaliningrad opposition newspaper Noviye kolesa [New Wheels], who had been in custody for nearly two years on charges of extortion, was released in the courtroom. On November 1, 2017, he was beaten up by security personnel in the course of a storming of the editorial office building, arrested, and, in his words, subjected to torture and violence in custody, while his newspaper was shut down pursuant to a lawsuit filed by the Federal Service for Supervision in the Sphere of Telecom, Information Technologies, and Mass Communications [Roskomnadzor].

- On July 12, 2019, unknown persons in masks detained former editor of the opposition Ingush publication FortangaRashid Maysigov short-term. A search was conducted at his home, in the course of which a bag with a white powder was allegedly Nothing was known about the whereabouts of the short-term detainee over the course of 24 hours. In the words of his lawyer, law enforcement agency employees were torturing the journalist in Nazran’s prison. On November 19, Maysigov was transferred to house arrest.

- On September 10, 2019, the Vologda City Court ordered indemnification in an amount of 50 thousand roubles to be paid to local blogger Yevgeny Domozhirov, acquitted in a case of defamation and extremism. The court found the activist not guilty under the Criminal Code articles on incitement of hatred and defamation; however, it did order 60 hours of compulsory labour for insulting a policeman.

PRISON TERMS FOR BLOGGERS AND ONLINE ACTIVISTS FOR “INCITING HATE”, “EXTREMISM”, “TERRORISM” AND “REHABILITATION OF NAZISM”

The “Golunov effect” was short-lived, however. Law enforcement agencies closely monitor social networks and local media with the aim of identifying publications on the basis of which they subsequently initiate criminal cases. In the course of the investigations in these criminal cases, media workers and their loved ones are subjected to fierce pressure: searches, confiscation of documents and equipment, beatings, restriction or deprivation of liberty, arrest of bank accounts, and so on. What Russian bloggers and journalists need to fear most of all are prosecutions under the following articles of the Criminal Code:

Incitement of hate (Article 282 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation):

- In January 2018, the Magas District Court of Ingushetia sentenced Mahomed Khazbiyev, editor-in-chief of the Ingushetia.orgwebsite, to two years and 11 months of deprivation of liberty in a prison settlement colony, as well as a fine of 50 thousand roubles. Khazbiyev was found guilty of “inciting hate” for Ingushetia’s head Yunus-Bek Yevkurov, local authorities, and the law enforcement system, as well as of illegal possession of weapons.

- In September 2019, the Presnensky District Court of Moscow sentenced blogger Vladislav Sinitsa, who was being charged with inciting hate with the threat of violence (Part 2 of Article 282), to five years of deprivation of liberty for a tweet in which he allegedly was calling on subscribers to commit violence towards the children of security personnel.

Calls for extremist activity (Article 280 of the Criminal Code):

- In June 2018, the Toropetsky District Court of Tver Oblast issued a verdict in the case of Vladimir Yegorov, who was being charged with publicly calling for extremist activities on the internet. The opposition activist was found guilty and given a suspended sentence of two years of deprivation of liberty and three years of probation and banned from moderating websites. The court likewise ordered the removal of the CPU from his personal computer. Serving as the pretext for the prosecution was his post on the VKontakte network, which contained a photograph of Putin and text about how the propaganda controlled by the special services is aimed at absolving the head of state by shifting the blame for all of the authorities’ blunders onto other officials.

Public calls to carry out terrorist activity or public justification of terrorism committed via the media (Article205, Part 2):

- On February 6, 2019, the Investigative Committee of Pskov Oblast opened up a criminal case against Svetlana Prokopieva. The pretext for opening the case became her op-ed on the Pskovskaya lenta novostey[Pskov News Feed] website, which was also read on the air on Ekho Moskvy v Pskove [Ekho Moskvy in Pskov]. The column was devoted to an analysis of the reason why 17-year-old Mikhail Zhlobitsky blew himself up in the Arkhangelsk Oblast FSB Administration building on October 31, 2018. Searches took place in the building where Prokopieva lives and at the Ekho Moskvy v Pskove radio station editorial office; the journalist’s bank accounts were arrested.

Rehabilitation of nazism (Article 354 of the Criminal Code):