Author of the report- National Union of Journalists of Ukraine

PHOTO: Stanislav Yurchenko, Graty

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Ukraine, 277 cases of attacks/threats against professional and citizen media workers and editorial offices of both traditional and online publications were identified and analysed in the course of the research for 2022. Data for the study were collected using open-source content analysis in Ukrainian, Russian and English. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 1. The study also includes data from a survey of approximately 100 affected media workers, including those who worked in Russian-occupied territories, undertaken by the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine as part of the project “Journalists are important. Stories of life and work in wartime”.

- Since the Russian Federation’s invasion in 2022, 12 media representatives died while performing their professional duties in Ukraine. At least 36 cases of attempted murder were recorded, including attacks committed in Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic.

- 44 percent of the incidents that occurred in Ukrainian territory in 2022 were committed by members of the Russian military.

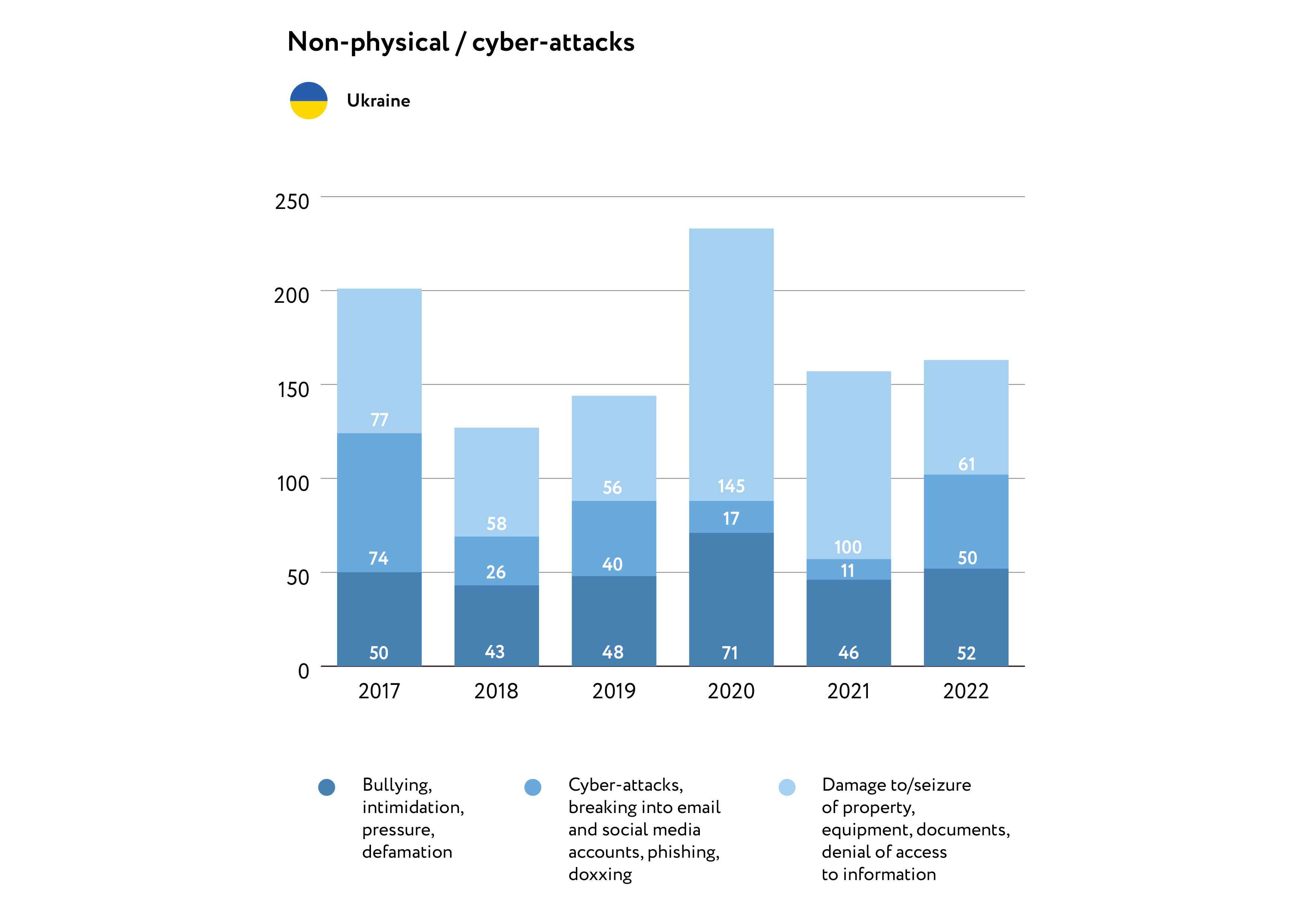

- Ukrainian media faced an increase in the number of cyberattacks. At least 42 incidents were recorded in 2022, nearly all of which took place after February 24, 2022. In 2021 there were only 11 recorded incidents.

Due to the continued occupation of significant portions of Ukrainian territory, some information about attacks against journalists is not available. It is likely that new information about these incidents, including those which took place in 2022, will be uncovered in the future, particularly if more territory is de-occupied.

2/ THE CURRENT SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN UKRAINE

Russia’s full-scale invasion had a devastating impact on every aspect of life in Ukraine, including for the media. There has been a significant reduction in the number of people working in the media in general. Many journalists have been forced to leave the country for the safety of themselves and their families, while many male journalists have joined the army or the defence forces. During the war, businesses, including large corporations, stopped allocating funding for advertising campaigns. Consequently, media outlets across the country reported a significant drop in advertising revenue, with some newspapers receiving revenue primarily from obituaries and messages of congratulations.

On February 24, 2022, during the first days of the invasion, the information program “United News” was launched to give regular updates to the people of Ukraine. The content is produced by the Public Broadcasting Company, the Rada TV channel and three media holdings: 1+1 Media, Starlight Media and Inter Media Group.

Additionally, in early April, the Broadcasting, Radiocommunications & Television Company forcibly switched over a network of T2 channels –Channel 5, Priamyi and Espreso TV– affiliated with former president Petro Poroshenko to the United News broadcast. The management of these TV channels expressed concerns about broadcasting round-the-clock content, in which their teams have no production involvement. These TV channels broadcast the United News telethon in blocks, alternating it with their own content, which is available both online and via satellite TV.

In July 2022, billionaire Ukrainian media tycoon, Rinat Akhmetov, announced that his investment company, Media Group Ukraine, would hand over its television and print media licences to the Ukrainian government. Any related online media outlets stopped updating their content. This followed the introduction of a law in 2021 relating to oligarchs and so-called “deoligarchisation” (“On the prevention of threats to national security associated with the excessive influence of persons with significant economic or political weight in public life (oligarchs)”), restricting the rights of such individuals in Ukraine.

A few months later, former employees of Media Group Ukraine launched a new media project, “We Are Ukraine”.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

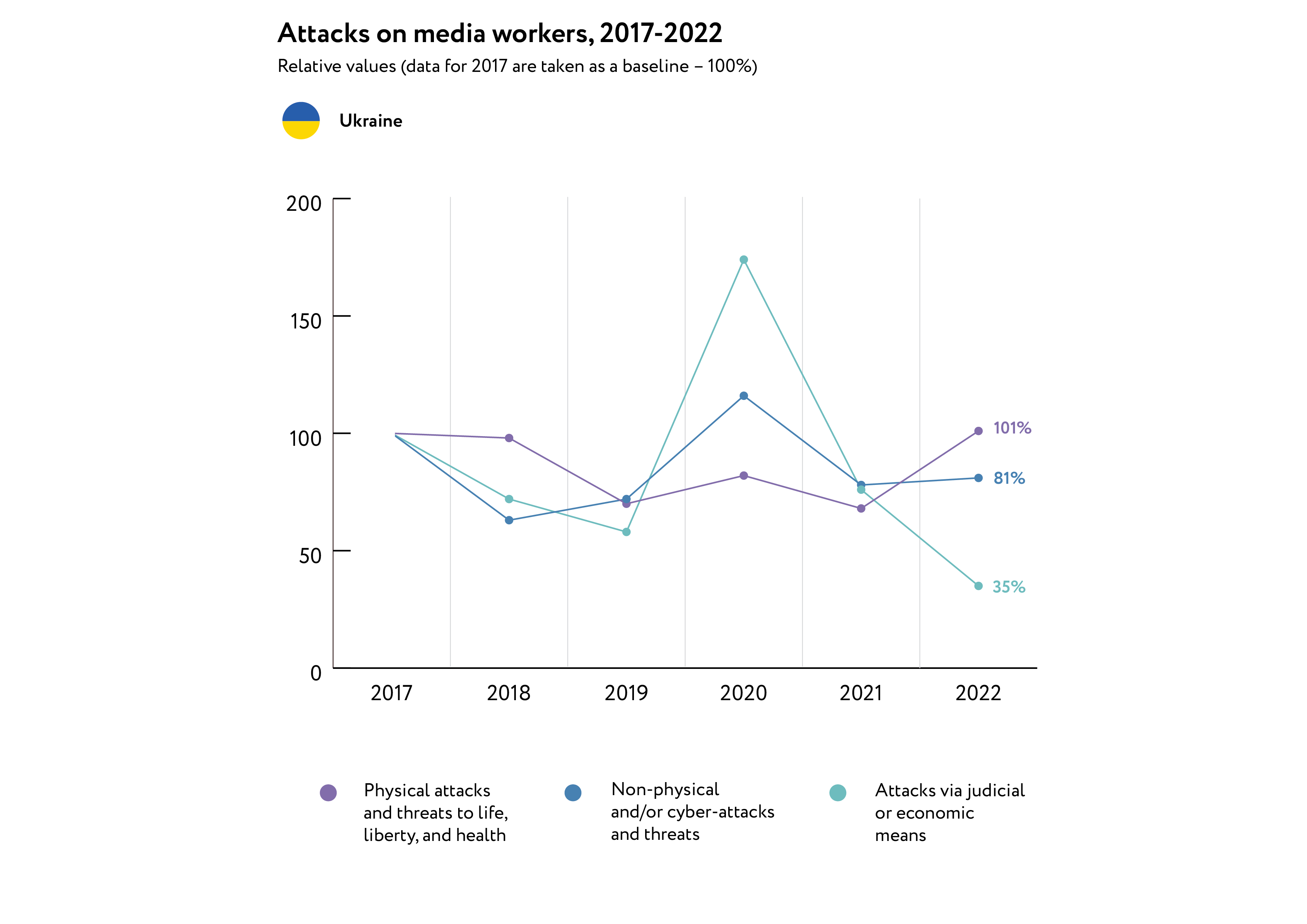

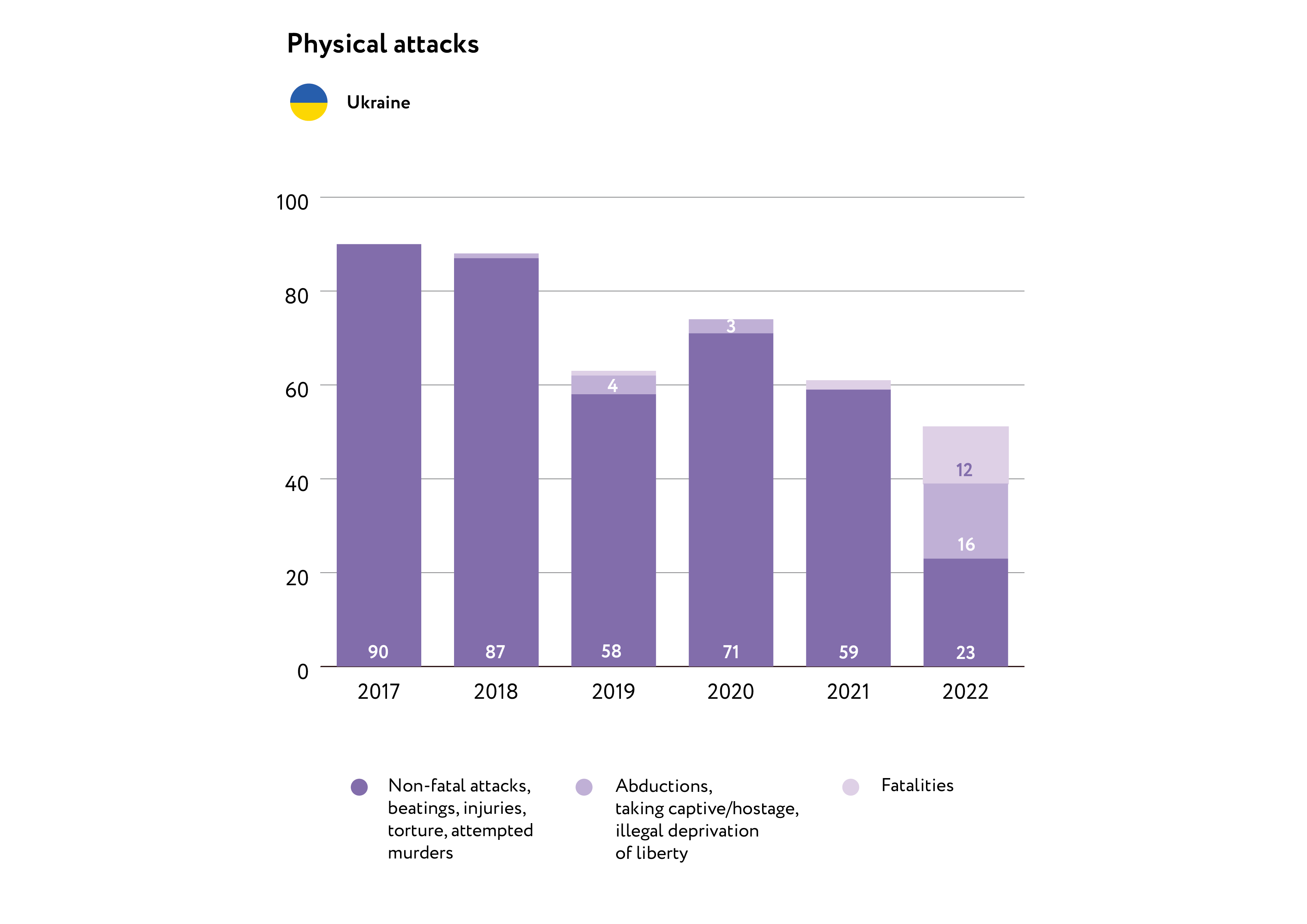

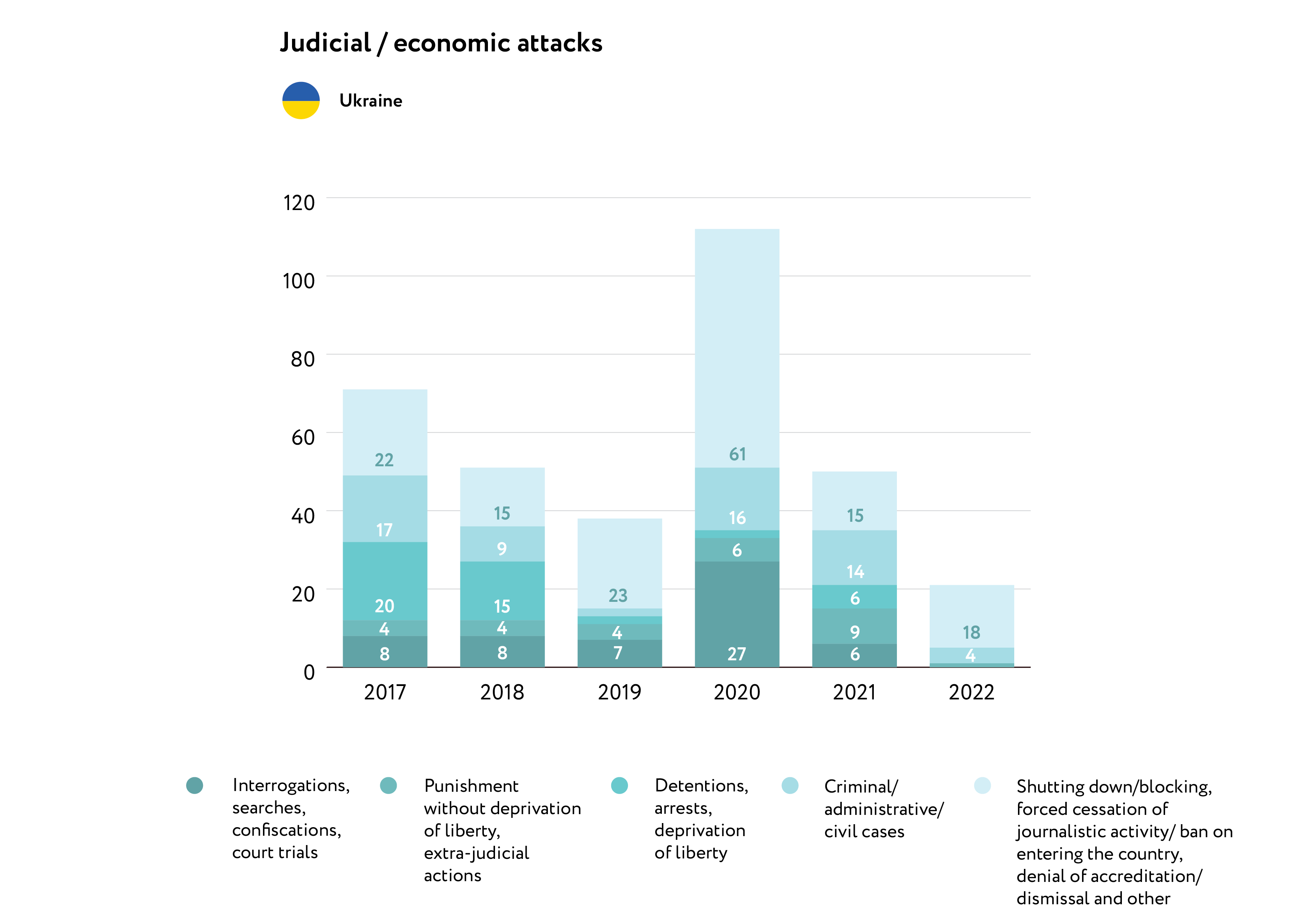

Figure 1 presents a quantitative analysis of attacks on media workers in Ukraine between 2017 and 2022. From 2017 to 2019, there was a decrease in the number of threats to journalists, especially attacks via judicial and/or economic means. In 2020, amidst local elections and pandemic restrictions, the number of attacks of this kind increased. After the easing of quarantine restrictions in 2021 and the end of the elections, the number of incidents returned to their previous level.

On February 24, 2022, thousands of Ukrainian journalists found themselves becoming frontline correspondents. Russia’s full-scale invasion also attracted the attention of foreign journalists, who quickly arrived in Ukraine to report on these events.

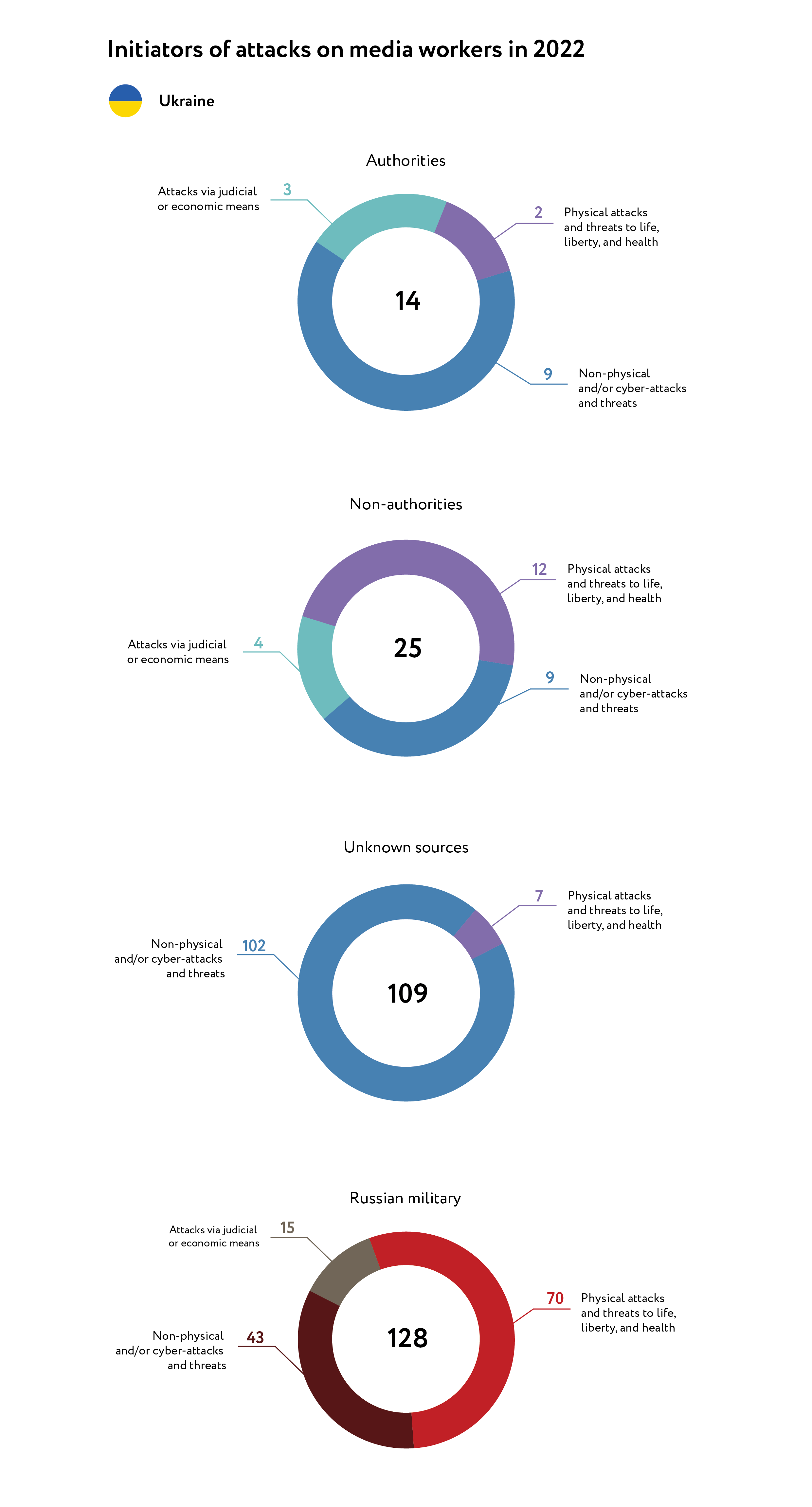

Due to the outbreak of the war, an additional category of threat was added to the Media Risk Map: “from the Russian military”. In 2022, the Russian armed forces were responsible for 46 percent of attacks against journalists in Ukraine. Figure 2 presents initiators of attacks on media workers in 2022. Last year also saw a large increase in threats from unknown perpetrators, bolstered by the high number of hacker and DDoS attacks on the Ukrainian media, as well as harassment and threats. Due to the nature of cyberattacks, it is often difficult to pinpoint the source of the threat, but most research suggests that these attacks were ordered by Russia.

4/ KILLING OF JOURNALISTS

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, 46 media workers were killed, including those who were serving in the armed forces.

Verified data confirms that 12 journalists and producers died as a result of enemy shelling while performing their professional duties. This number includes five foreign journalists: Frédéric Leclerc-Imhoff, Mantas Kvedaravičius, Pierre Zakrzewski, Oksana Baulina, Brent Renault; and three Ukrainian journalists: Oleksandra Kuvshinova, Maks Levin and Yevheniy Sakun.

At least four Ukrainian media workers were tortured and killed in Russian-occupied territories:

- On March 18, the Russian military illegally detained journalist Yevgeny Bal near his home, after police found “compromising” photos of Bal with the Ukrainian military. He was kept in a basement for 3 days, during which time he was tortured and beaten. Bal was eventually released but died from his injuries on April 2.

- The body of freelance journalist Zoreslav Zamoysky was found in Bucha, with forensic examinations suggesting his death was “violent”. Zamoysky regularly covered the war on his Facebook page, where he had around 1,000 followers. The journalist posted his last message on March 4.

- The body of journalist Roman Nezhyborets was found buried in the village of Yahidne in northern Ukraine. His body was discovered by locals after the withdrawal of Russian troops from the area. Russian soldiers occupied Yahidne on March 5, forcing residents into underground shelters and confiscating their phones. Nezhiborets, who was with his family in a shelter in Yahidne, tried to call his mother to get her to ask his colleagues to remove him from several group chats, including Dytynets, a television broadcaster, employee chats. On March 5, Russian troops caught Nezhiborets calling his mother and took him away. On April 6, after the city was liberated from Russian control, Ukrainian volunteers discovered Nezhiborets’s body in a grave in Yahidne. His hands were tied and he had sustained gunshot wounds to his knees.

- From the very first day of the invasion, photojournalist Ihor Hudenko covered the events in Kharkiv. On February 26, Gudenko went to the Kharkiv ring road to film military developments. After heavy shelling of the city, communication with the journalist was lost. It later became clear that Gudenko had died while filming on Natalii Uzhvii Street in Kharkiv. Gudenko was buried on April 9.

5/ OTHER WAR CRIMES COMMITTED AGAINST MEDIA WORKERS IN UKRAINIAN-CONTROLLED TERRITORIES AFTER 24/02/2022

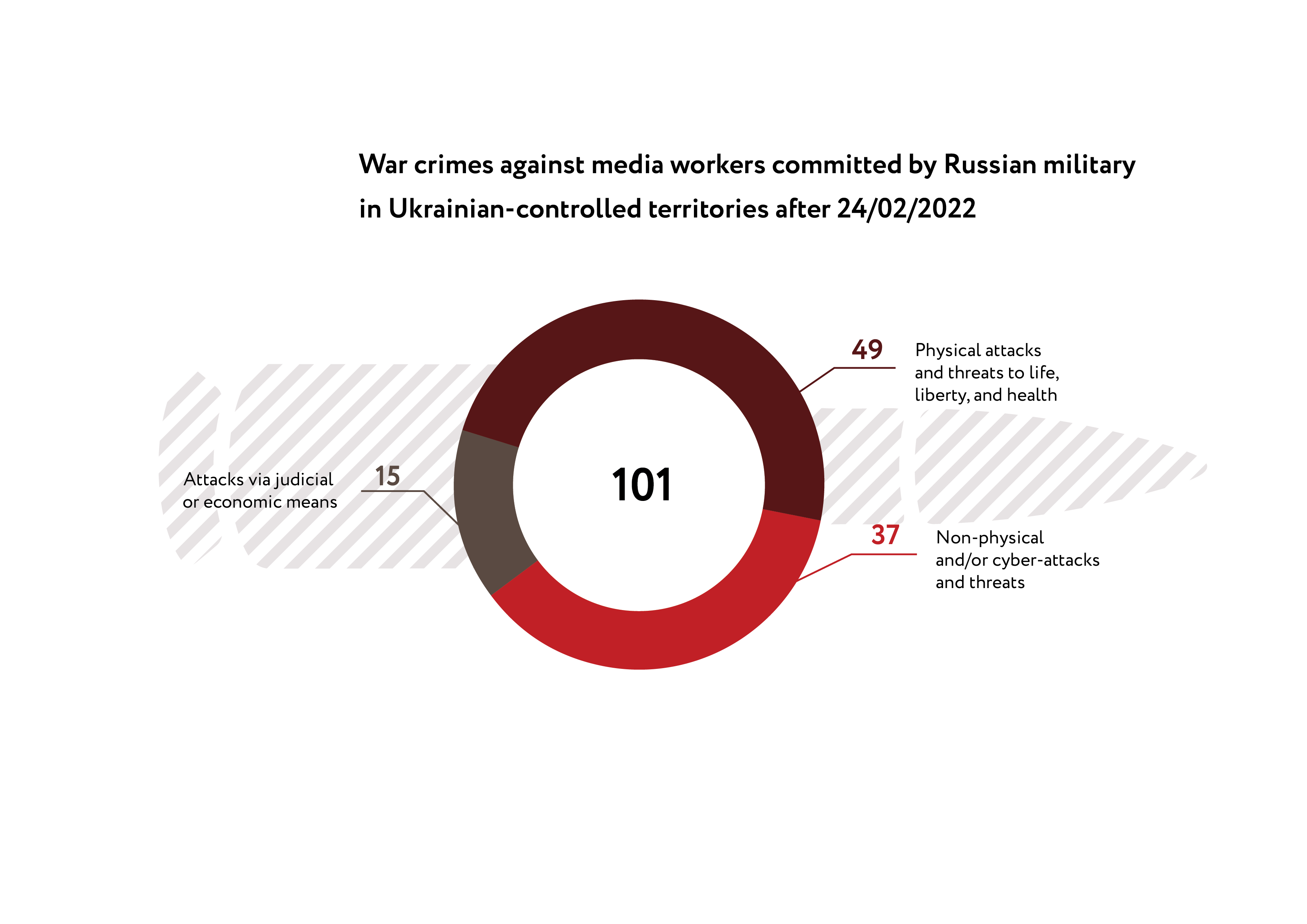

Since February 24, 2022, until the end of the year there were 101 cases of attacks against journalists committed in Ukrainian territories by the Russian military (i.e., all regions excluding Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic), some of which have been or are still under Russian control. It is worth noting that this number refers to verified cases. Ukrainian territories under occupation are subject to an information vacuum. There is a distinct probability that new information and evidence of crimes will emerge if more territories are de-occupied, as was the case after the de-occupation of Bucha, Irpin, Izyum and Kherson. Under international law, deliberate attacks against journalists constitute a war crime.

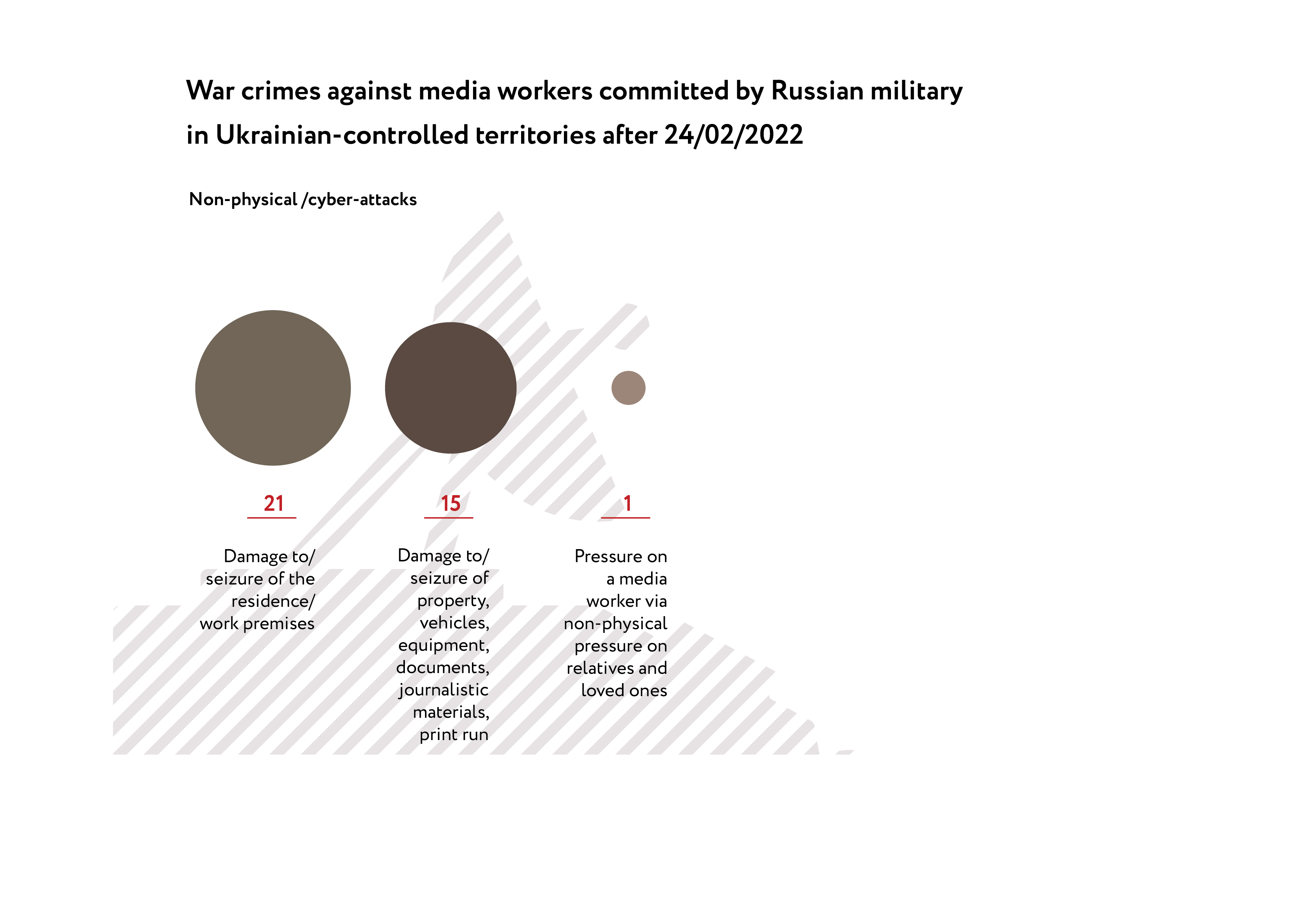

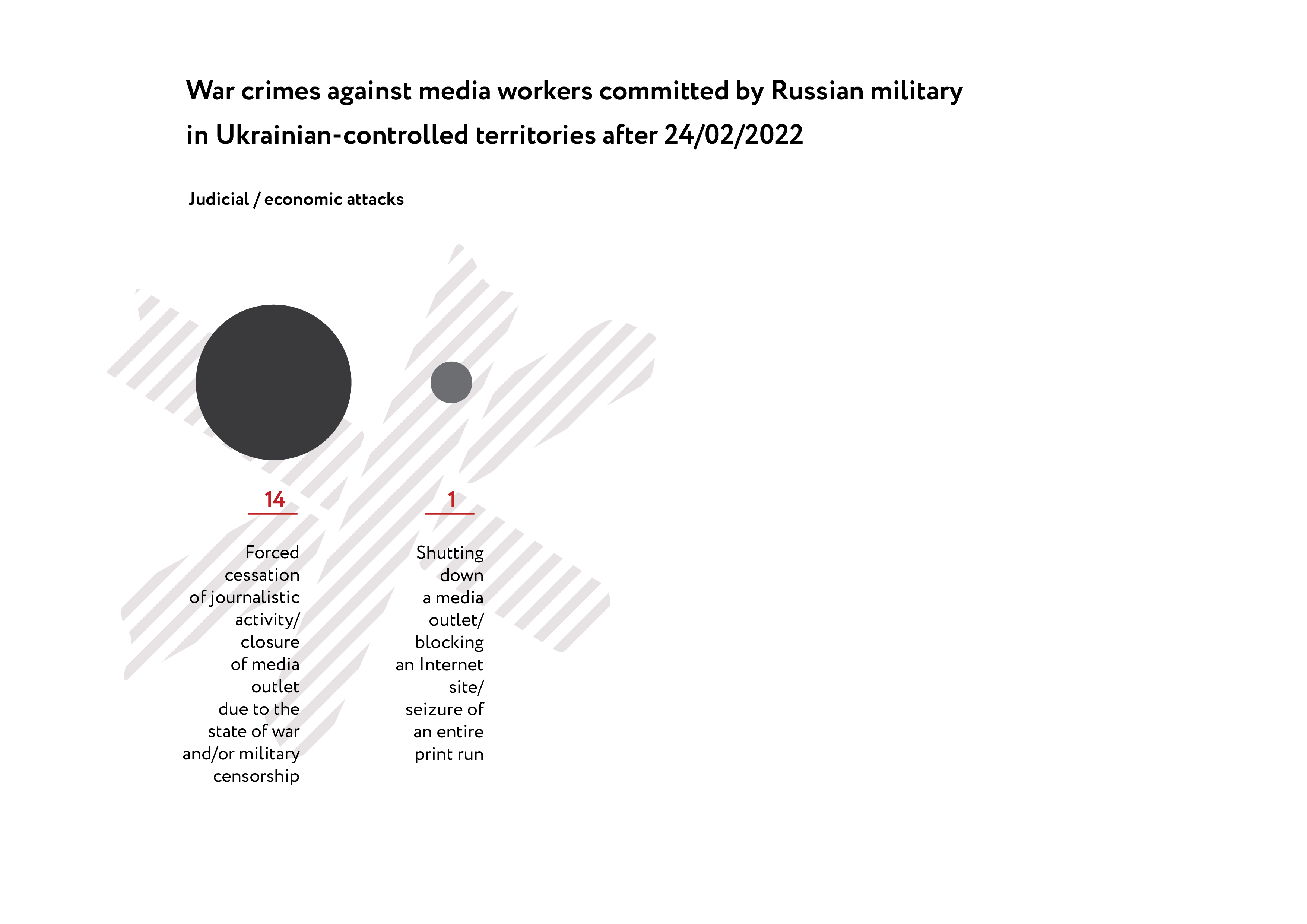

Of the incidents recorded since February 24, 2022, 49 were attacks and threats of a physical nature, 37 were attacks of a non-physical nature and/or cyberattacks, and 15 were attacks via judicial and/or economic means (Figure 3). It is worth noting that the attacks presented in the Figures below were committed by the Russian military only.

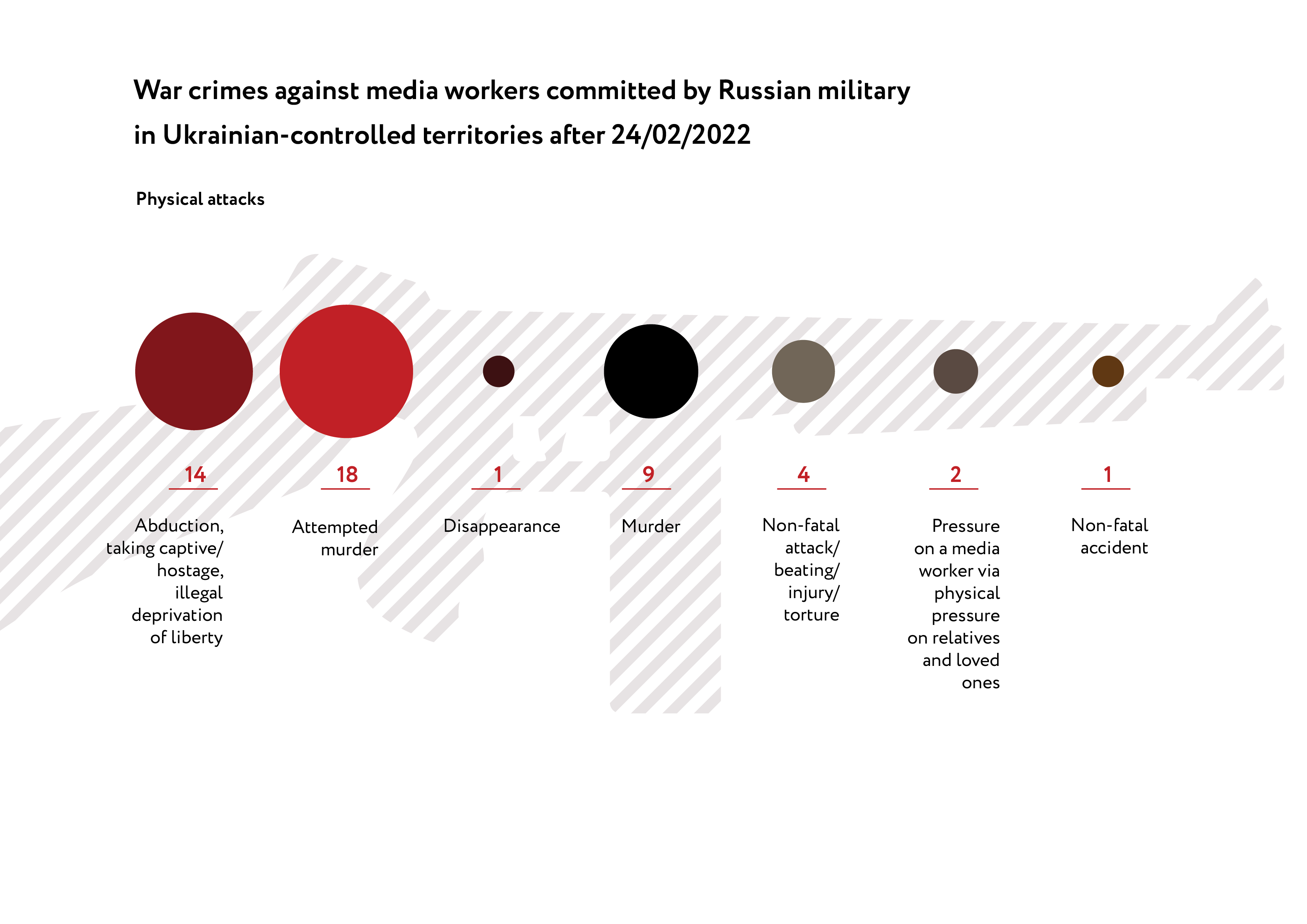

Contrary to accepted rules of engagement, during the Russian-Ukrainian war journalists have been targeted, not protected. There were multiple cases of physical attacks (Figure 4), at least 18 of which were classed as attempted murder. The Russian military continues to purposefully shoot at people and vehicles with press markings.

As Russia occupied new territories, media workers became amongst the first targets for persecution. The occupiers attempted to force them to cooperate through physical and psychological means. In some cases, even when journalists managed to escape an occupied territory, their relatives and friends were targeted. For example:

- On March 23, the Russian military searched the residence of the news site RIA Melitopol’s editor-in-chief, Svetlana Zalizetskaya, who managed to escape to Ukrainian-controlled territory in the early days of the war, in order to continue her journalistic work. Unable to find Svetlana, Russian soldiers took her 75-year-old father hostage. They demanded that Svetlana travel back to Melitopol to ensure his release. After several days of negotiations and both public and international attention, her father was released, but in return Svetlana was forced to give access to her journalistic resources, after which the RIA Melitopol editorial office was ransacked.

At least 14 incidents related to the kidnapping and/or wrongful imprisonment of media workers were recorded. In many of these cases, journalists were kept in squalid conditions, deprived of legal and medical assistance, and were subjected to both physical and psychological abuse. Media workers were forced to cooperate with the Russian side, who accused them of espionage and demanded they “testify” against their colleagues. Examples include:

- On March 5, the Russian military abducted a fixer who was working for Radio France. His car, which had press markings, was fired upon. According to Reporters Without Borders, he was beaten, shocked with electricity, kept in a freezing and damp basement, interrogated, and not given food for 48 hours. He was then thrown into a ditch full of dead animals, where he was subjected to a mock execution. The military forced him to write a declaration of support for the Russian army and their invasion of Ukraine. On March 13, the journalist was released.

- On March 12, journalist Oleg Baturin disappeared in Kakhovka. The journalist’s wife said that he left the house without a phone or ID to meet a friend for 20 minutes. The journalist did not get in touch with her for several days. On March 20, Baturin announced that he had been freed. His sister, Olga Perepelitsa, described the kidnapping on Facebook (quoting Baturin): “On March 12, at 17:00, they grabbed me at the Kakhovka bus station. I was beaten. Humiliated. Threatened. They said they would kill me. I was held for almost eight days. 187 hours. Almost no food. Several days without water. No soap or a change of clothes. They wanted to break me, crush me”. On April 16, invading Russian forces began to threaten Baturin’s relatives, who remained in the occupied territories. They demand that Oleg cease his journalistic activities in Ukrainian-controlled areas.

- On March 21, the Russian military broke into the apartments of MV-Holding journalists Evgenia Boryan, Yulia Olkhovska and Lyubov Chaika as well as the media group’s owner, Mykhaylo Kumok. The military later abducted Kumok’s wife and daughter. That evening, after a “discussion” about the need for cooperation, Mykhaylo and his family were released. Their mobile phones were confiscated.

- On September 20, the Russian military abducted Zhanna Kyselyova, the 54-year-old editor of the Kakhovska Zorya newspaper. The publication ceased operations after the invasion. On October 2, 2022, information was published online, suggesting that Kyselyova had been released.

In the occupied territories, many editorial offices and their equipment was destroyed during hostilities; others were seized and used for Russian propaganda purposes. This included computer equipment with confidential source information, as well as printing presses and radio transmitters. Fake, pro-Russian, versions of well-known local media began to appear, put together by local collaborators or specialists from Russia. Examples include:

- On May 9, the editor-in-chief of the Priazovsky Rabochiy newspaper learned that the occupying Russian authorities had published a pro-Russian newspaper with the publication’s branding, style and logo. The last edition of the real newspaper was released on February 23.

- On August 8, in Beryslav, invading forces seized the editorial office of the local Mayak newspaper and began to publish propaganda under its brand. An article about the anniversary of the baptism of Kievan Rus appeared on the front page under the headline “One Faith. One people. One country”.

- On December 18, after the de-occupation of the area, it was revealed that the Russian invading forces had printed a clone of a well-known local newspaper in order to spread propaganda. The style, font and name were used, but translated into Russian as “Rodnoye Pribuzhye”.

During the retreat of the Russian army, media equipment was removed or destroyed. As such, Ukrainian media workers in de-occupied territories have to rebuild their livelihood from scratch. Most regional media are forced to seek help from international grant-making organisations, since their own finances will not cover even a fraction of these costs.

In front-line areas, Russian missiles destroyed a great deal of the television and radio infrastructure, as well as the offices of influential regional media outlets. Some editorial offices were targeted more than once, suggesting that this was intentional.

- On March 2, during the shelling of Kharkiv, the office and press centre of the local KHARKIV Today news agency were damaged. Shrapnel destroyed equipment, furniture, and documents. These premises remain unusable.

- On April 12, Obrii Izyumshchiny news website editor-in-chief, Konstantin Grigorenko, reported that their editorial office had been damaged. The Russian military broke down the doors and destroyed the equipment in the office.

- On July 15, in the front-line village of Zolochiv, the editorial office of the local newspaper Zorya was shelled for a second time, sustaining significant damage. The building had only just been repaired following the first round of shelling in April. The Zorya team is confident that these attacks were targeted since neighbouring buildings were not shelled.

- On September 22, during the Russian shelling of Zaporizhzhia, a branch of the Public Broadcaster was damaged. Windows were shattered and nearby cars were destroyed, however, fortunately, nobody was hurt.

As a result of sustained Russian rocket and artillery attacks, many journalists’ homes have been destroyed. Some of them have since become internally displaced persons and refugees, alongside their fellow journalists fleeing occupied territories.

- Olena Kalaytan, editor-in-chief of Priazovsky Rabochiy, the oldest newspaper in Mariupol, lived in occupied Mariupol for 23 days, under constant bombardment. She and her son later left, on foot, for Ukrainian-controlled territory. All her belongings were destroyed.

- Lydia Tarash, editor-in-chief of Nashe Slovo, from the Donetsk region, spent three weeks in a damp basement with her family, fleeing constant shelling. She was eventually able to reach Ukrainian-controlled territory. Due to financial difficulties, the work of the publication has been halted.

- Yevgeniya Virlych, the editor-in-chief of one of the most famous news outlets in Kherson, Kavun.City, continued to work as a journalist in the occupied area until July. She and her husband hid from the FSB, moved apartments and sent coded messages. They were eventually forced to leave their home city for security reasons. Virlych currently lives in Kyiv and continues to work for Kavun.City, as well as writing elsewhere about Kherson.

- Sergey Starushko worked for the Novosti Berdyansk radio station, as well as the Berdyansk Vedomosti newspaper and Molodoye TV, which were taken over by Russian invading forces in early March 2022. He was threatened and forced to cooperate. On April 11, he was forced to leave Berdyansk for Ukrainian-controlled territory.

Attacks of a non-physical nature and/or cyberattacks against Ukrainian media workers were primarily committed by representatives of the Russian military. In 2022, 43 cyberattacks took place in rapid succession (these attacks are not presented in the Figure below, as they were committed by unknown sources). Based on content analysis and connections to military events, there is sufficient evidence to believe that most of these attacks were ordered by Russia. It is still worth noting that regional media outlets, generally speaking, had weak IT security protocols in place, so were vulnerable to such attacks. However, after several waves of attacks, these organisations, with the help of donors, enlisted the support of security specialists, and also created pages on alternative platforms such as Facebook, Telegram and Instagram.

Attacks under the subcategory “harassment, intimidation, threats of violence and death, including online threats” make up one of the main methods of pressure against journalists. At least 41 incidents of this type were recorded, including:

- From March 15 to April 16, 2022, Racurs.ua journalist, Yury Konkevich, received 11 threatening emails from Russia. Earlier, the publication wrote that nearly all of their articles contain content which is banned by the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

- On March 25, a number of Ukrainian media outlets received threatening emails suggesting that the Russian security services had their journalists’ personal information. “After the Russian army occupies your area, you will be interrogated and sent to prison”, the emails read.

- The Zaporizhzhia news site 061.ua continues to receive threatening emails on a regular basis, sent from different email providers, including mail.ru. These emails contain threats of criminal prosecution for “spreading false information and lies”.

- Volyn Online editor, Maryana Metelskaya, said she received at least six emails threatening criminal liability for spreading false information and propaganda.

The Russian armed forces committed 15 recorded attacks via judicial and/or economic means (Figure 6). All of these related to the forced cessation of journalistic activities and the forced closure of media outlets in Russian-occupied territories. Many journalists were forced to make this decision, as continuing to work in these regions in any objective manner had become impossible. This number only refers to cases where journalists explicitly reported this decision. At the same time, a large number of journalists have privately suspended their activities to minimise the risks to their lives and health.

According to The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, due to economic circumstances, around a third of Ukrainian media outlets either suspended operations or stopped working entirely in the first few months after the invasion. This was the case in both occupied and government-controlled territories. Even media outlets that are still operating are vulnerable to closure at any moment, due to an inability to pay their employees, the increased prices for printing services and other financial pressures.

6/ ATTACKS ON MEDIA WORKERS BY CIVILIANS, UKRAINIAN AUTHORITIES AND OTHERS (NON-WAR RELATED INCIDENTS).

In 2022, there was a record low in the number of attacks perpetrated by Ukrainian state and non-state actors. This can be attributed to the fact that Ukrainian society rallied in the fight against a common enemy. The entire Ukrainian information sphere is filled with the topic of war, the front line and international achievements. Journalistic investigations and scrutiny of the actions of Ukrainian authorities faded into the background, therefore, the number of reprisals decreased.

Since the beginning of 2022, 21 incidents of physical attacks on media workers were recorded. The majority of these incidents, 14, were recorded in the first two months of 2022, prior to the invasion. Examples of physical attacks in 2022 include:

- On January 5, unidentified men assaulted Anton Vorobyov, a journalist from Kremenchuk TV, while he was reporting at the local hospital.

- On January 28, a film crew from StopCor arrived in the capital on assignment. There was a lavish celebration, presumably celebrating the birthday of the President of the National Academy of Medicine. The guests at the event were aggressive, and blocked journalist Ilya Shevchenko in the hall, before taking his phone and smashing it. His camera and microphone were also damaged.

- On April 30, Belarusian journalist Dzianis Stadzhi, who had moved to Ukraine, was attacked by unknown individuals. The journalist was found unconscious by his wife, who, after the start of the Russian invasion, took their child from the capital to Western Ukraine, but returned when Denis stopped responding to messages. Their apartment was raided, and information storage devices were stolen. It is suspected that the attack occurred to gain access to the Belarusian community groups on Telegram, for which he is the admin.

- On November 2, the Priamyi TV film crew was covering a peaceful demonstration of workers at a local factory. Law enforcement arrived and immediately demanded that the journalists leave, after which they attacked journalist Galina Fedorchenko and videographer Alexander Dubin, smashing the latter’s camera in the process.

One journalist was the victim of an attempted murder:

- On December 21, Kherson journalist Konstantin Ryzhenko, who lives in Kyiv, reported that an unknown person shot at him several times. The journalist was saved by his bulletproof vest. He published a photo of damaged armour plates and a statement to the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU).

In 2022, there were six recorded attacks via judicial and/or economic means, perpetrated by government officials and civilians in Ukraine.

- On February 17, Zerkalo Nedeli reported that the former mayor of Kyiv, Leonid Chernovetsky, had filed two lawsuits against them, seeking “compensation for moral damage”.

- On November 29, the Tsukrogidromash hydraulic plant in the Kirovohrad region filed a lawsuit against CBN and its editor-in-chief, Andrey Lysenko. They demanded a retraction of an October 14 article, which stated, “The Kropyvnytsia enterprise fell under the sanctions of the National Security and Defence Council”. The lawsuit alleged the article damaged their business reputation. A few days after publication, representatives from the plant had demanded, in private, that the publication remove the article and issue an apology.

- On January 6, Igor Fedusenko, who worked at the communal enterprise Boguslav Centre for the Provision of Social Services, was forced to write a resignation letter. In an off-the-record conversation, Fedusenko was told that this was due to his daughter, radio journalist Oksana Fedusenko, criticising the local authorities.

The number of non-physical and/or cyberattacks committed by civilians and government officials, outside the context of war, dropped to 18:

- On May 10, Belyaevka.city editor-in-chief, Galina Halimonik, who temporarily fled to Poland after the invasion, said that she was being threatened on Facebook by another resident of her village. These threats were reported to the police, and later to the prosecutor’s office.

- On July 30, Sevgil Musaieva, editor-in-chief of the independent Ukrainian news site Ukrainska Pravda, along with Sonya Lukashova, a correspondent for the publication, began receiving threatening phone calls and messages after Ukrayinska Pravda published an investigation into the dismissal of Ombudsman Lyudmila Denisova.

- On September 14, the film crew of the local Kamianets-Podilskyi TV channel was prevented from covering a Khmelnytsky Oblast Coordinating Council meeting, the purpose of which was to discuss the city’s winter preparations. Officials claimed that private matters were to be discussed. However, there was no vote in favour of the meeting taking place behind closed doors.

- On November 4, Tetiana Tsirulnik, the editor-in-chief of Kolo reported that she had been harassed online after she published news about the secretary of the Poltava city council, Andrey Karpov. Karpov accused the journalist of distorting information, and his supporters began to post abusive comments about Tsirulnik beneath his Facebook post.

7/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS IN 2021

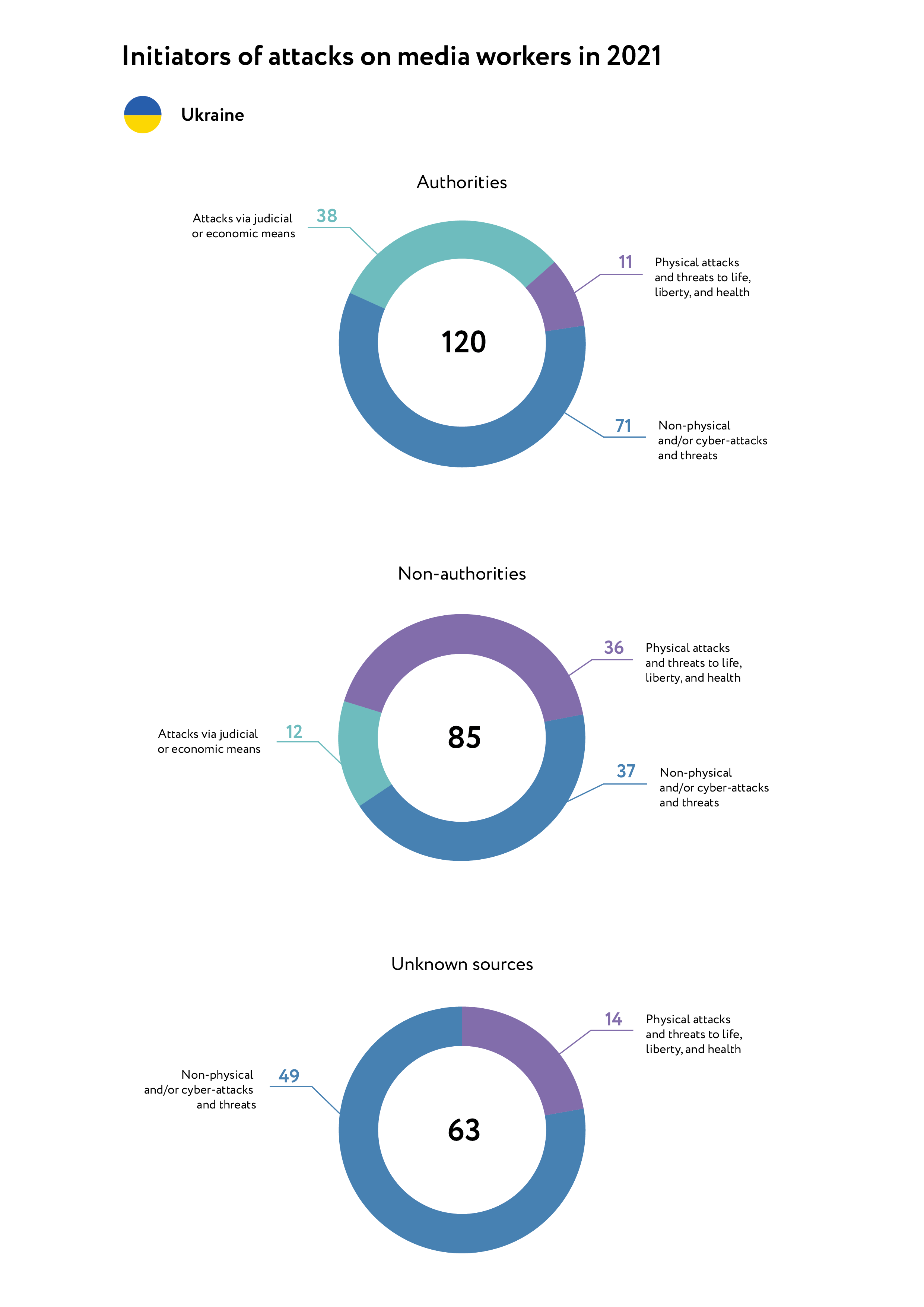

In Ukraine, 268 cases of attacks/threats against professional and civilian media workers, and editorial offices of traditional and online publications were recorded in 2021. This marks a clear improvement on the number of incidents in 2020, when there were 422 recorded incidents.

- In 2021, the number of attacks on journalists decreased by 37 percent compared to 2020.

- In 45 percent of cases, attacks on media workers were committed by government officials.

- Non-physical attacks remained the most common method of exerting pressure on media workers. This primarily consisted of illegally obstructing journalists and damaging their equipment. A common method of intimidation was arson and property damage.

A separate police department was created, specifically to investigate violations of the rights of journalists. There are representatives of this department in each region of the country, who are in direct contact with the National Union of Journalists. With this mechanism in place, police and investigators began to understand that incidents involving journalists could not be ignored. Investigations began to proceed at a much faster pace, and there was an increase in the number of cases being brought to trial, rather than simply being closed due to lack of evidence.

An example of this can be seen following an incident in Odessa on February 10, 2021. A film crew from Channel 7, consisting of Igor Gvozdev and Viktor Nadyuk, was attacked by young people, while they were filming a story about violations of trade rules at the local market. By February 18, courts in Odesa found one of their attackers guilty of committing a criminal offence and gave them a 2-year non-custodial sentence.

In 2021, as it can be seen from Figure 7, 45 percent of attacks were committed by government officials, 32 percent by individuals who were not representatives of the authorities, and 23 percent by unknown persons.

All targeted physical attacks recorded in 2021 were non-fatal (Figure 8). One fatal incident took place on May 13 on the Dnipro-Reshetylivka highway. A film crew from the NTN TV channel, along with journalist Vladimir Nepiypivo and videographer Konstantin Khudolei, died when their car collided with a truck.

Most attacks, 81 percent, were committed by individuals not associated with the authorities, or from unknown persons. Some examples are given below:

- On February 4, a journalist was attacked by nationalists during a live broadcast near the Shevchenko district police department. They started throwing snow at the film crew of the Nash TV channel and demanded that they leave. Alexei Palchunov’s microphone was pulled from his hands, and he was punched in the head and jaw. When the film crew tried to leave, they were verbally abused and assaulted again.

- On July 2, in Dnipro, during the filming of a story about the dismantling of illegal constructions, film crews from two local TV channels, OTV and D1, were assaulted. The assailants attacked the journalists and broke their equipment in order to seize the footage.

- On August 8, a group of journalists from Green Leaf were assaulted while working on their “Beach Control 2021” project. During an inspection of one of the beaches, journalist Yuri Dyachenko was attacked. An unknown woman approached the journalist from behind and struck him on the head with an iron object.

- On October 30, members of the right-wing group Right Sector attacked a NASH TV channel film crew consisting of journalists Maxim Gerasimenko and Anna Ospipenko, as well as their videographer. They were working in the Sumy region as part of the project “Our Land Is Here”. The videographer was thrown to the ground and kicked. When Gerasimenko rushed over to help his colleague, he was struck in the face. The assailants also grabbed the microphone from the film crew, demanding that they stop filming. Gerasimenko’s lip was split, and the videographer sustained multiple bruises.

- On November 4, during a fire in the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, members of the clergy obstructed Magnolia TV journalist Alexander Tereshchenko and Segodnya journalist Igor Serov. Tereshchenko and Serov were prevented from accessing the scene and had their cameras damaged. During a live broadcast, one of the journalists was attacked by a group of men.

The number of attacks of a non-physical nature has slightly decreased compared to 2020, suggesting that the sharp increase in this type of attack in 2020 was due to the local elections and pandemic restrictions. In 2021, these restrictions were eased and the elections finished, and as such the figures returned to 2019 levels.

Damage and seizure of property, equipment and materials, as well as deprivation of access to information remain the main method of non-physical pressure on journalists. These account for 100 of the 157 recorded attacks. Examples include:

- On February 2, unidentified individuals entered the courtyard of journalist Olga Ferrar’s home and smashed her car windows. Olga suggested that this was due to her journalistic activities, in particular, due to her recent publications about the work of the Rivne Regional Council, social issues, and the distribution of budget funds and land.

- On February 7, unknown individuals set fire to Vladimir Yegorov’s car, which was kept in a secure car park. Police officers managed to establish the approximate place from which the car park was breached. Yegorov suggested the incident was due to his journalistic and political activities. A few years prior to this incident another one of his cars was set on fire.

- On the night of April 20, two editors from the Dobkin Times had their cars set on fire. In addition to this, funeral wreaths were laid outside the entrance of their apartment buildings, and threatening messages were written on the wall. The journalists considered this to be a threat aimed at intimidating them and obstructing their journalistic work.

- On December 5, two cars belonging to ZIDO journalist Pavel Beletsky and his wife were set on fire. Police in the Transcarpathia region launched an investigation into the arson. Beletsky blamed the arson on his professional activities.

There were at least 11 cyberattacks and email/social media hacking incidents recorded in 2021:

- On February 2, the Aktualno website was subjected to a DDoS attack, which lasted for a day. The site’s editor-in-chief suggested that the attack could have occurred due to conflicts between local politicians and the leader of one of the Ukrainian political parties.

- On April 12, journalist Elena Dub reported that she had begun to receive threatening text messages. There was also a barrage of fake calls and messages originating from Russian numbers. The journalist also claimed that there were multiple attempts to hack into her personal accounts online. She suggested that this attack was due to her six years of work on Radio Liberty’s Crimea.Realities project.

- On September 8, a new wave of DDoS attacks took place against the website of Bukvy, an information service, where several high-profile investigations had recently been published.

- On September 9, a spam attack was launched against Dmitry Kuzubov, editor-in-chief of the Kharkiv online magazine Luk as well as the publication’s Telegram channel. This followed the publication of a video clip showing support for LGBT people. Shortly after the video was published, threats from anonymous accounts began to flood into the channel’s comments. Calls for an attack were spread throughout right-wing Telegram channels. Unknown individuals tried to gain access to Kuzubov’s messaging accounts. Prior to this, on September 7, a spam attack took place on the publication’s chat: in less than a minute, more than 2,000 messages were posted by anonymous accounts.

The number of attacks via judicial and/or economic means in 2021 decreased by two times in comparison to 2020 as it can be seen on Figure 10. In 76 percent of cases, by government officials initiated these attacks.

- On February 3, Prosecutor General Iryna Venediktova filed a civil suit against 5 Kanal journalist Yanina Sokolova citing damages to her honour, dignity, and reputation. This was as a result of an interview between Sokolova and a member of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine, in which they discussed Venediktova’s potential involvement in a corruption investigation.

- A former employee of the SBU, Dmytro Kuzka, filed a civil suit against the Grati newspaper, as well as journalist Anna Sokolova, for mentioning him in an article. Both the journalist and the newspaper received a court warning. Kuzka insisted that his inclusion in the article caused “moral damage” towards him.

- On November 29, the State Bureau of Investigation brought a criminal case against Yuri Butusov, editor of Censor.net, after a video was published of him shooting a howitzer. The video was subject to verification under Articles 414 and 437 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (“violation of the rules for handling weapons” and “planning for, initiating or conducting a war of aggression”). The journalist explained that the video was filmed during a military exercise.

In 2021, one incident related to the arrest of a media worker was recorded:

- On May 31, according to the Kherson Prosecutor’s Office, Oksana Shilo, a manager at the Kherson branch of the National Public Television and Radio Company of Ukraine, was detained under Article 208 of the Criminal Code. She was placed in a temporary detention facility and eventually released on bail on June 2, 2021. She was suspended without pay from June 3 to August 1. On October 15, her employment contract was terminated.

In summary, one can note a clear improvement in the level of safety of journalists in Ukraine 2021. Plans were in place to introduce new processes to further improve the safety of journalists in 2022, including crime prevention information campaigns. However, Russia’s full-scale invasion has drastically changed the priorities and needs of media workers in Ukraine.

ANNEX 1: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (UKRAINE)

- The National Union of Journalists of Ukraine is the largest organisation of journalists and other media workers in the country.

- The National Council of Television and Radio Broadcasting of Ukraine – a permanent collegial, supervisory and regulatory state body operating in the field of television and radio broadcasting.

- Online resources from the National Police of Ukraine.

- The national state news agency Ukrinform.

- Ukrainian News – one of the largest private news agencies in the country.

- The ZMINA human rights centre – a public organisation founded with the goal of building a country in which everyone can protect their rights.

- Magnolia-TV – a Ukrainian TV channel with a 24/7 broadcasting network, consisting of emergency news bulletins.

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty – an international non-profit broadcasting organisation.

- Telegram channels – a popular messaging tool in Ukraine, allowing for the fast publication of information.

- Publicly available Russian and Ukrainian-language online media.