PHOTO: GAZETA.UZ

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Uzbekistan, 110 attacks/threats against professional and civilian media workers, as well as editorial offices of traditional and online publications, were identified and analysed in the course of research for 2022. Data for the study were collected using open-source content analysis in Uzbek, Russian and English languages. This report also includes unpublished data obtained via expert interviews. A list of the main sources is provided in Annex 1.

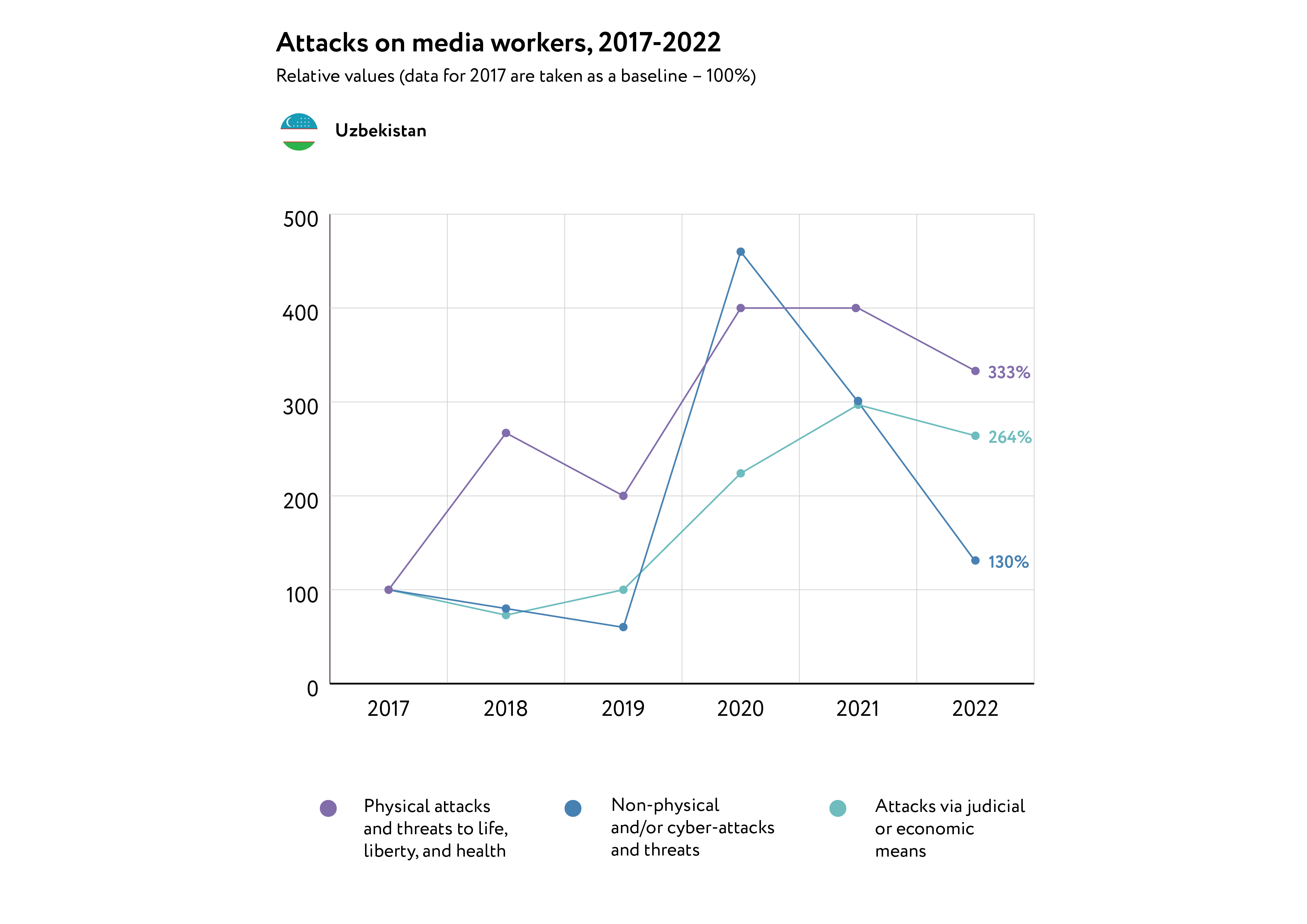

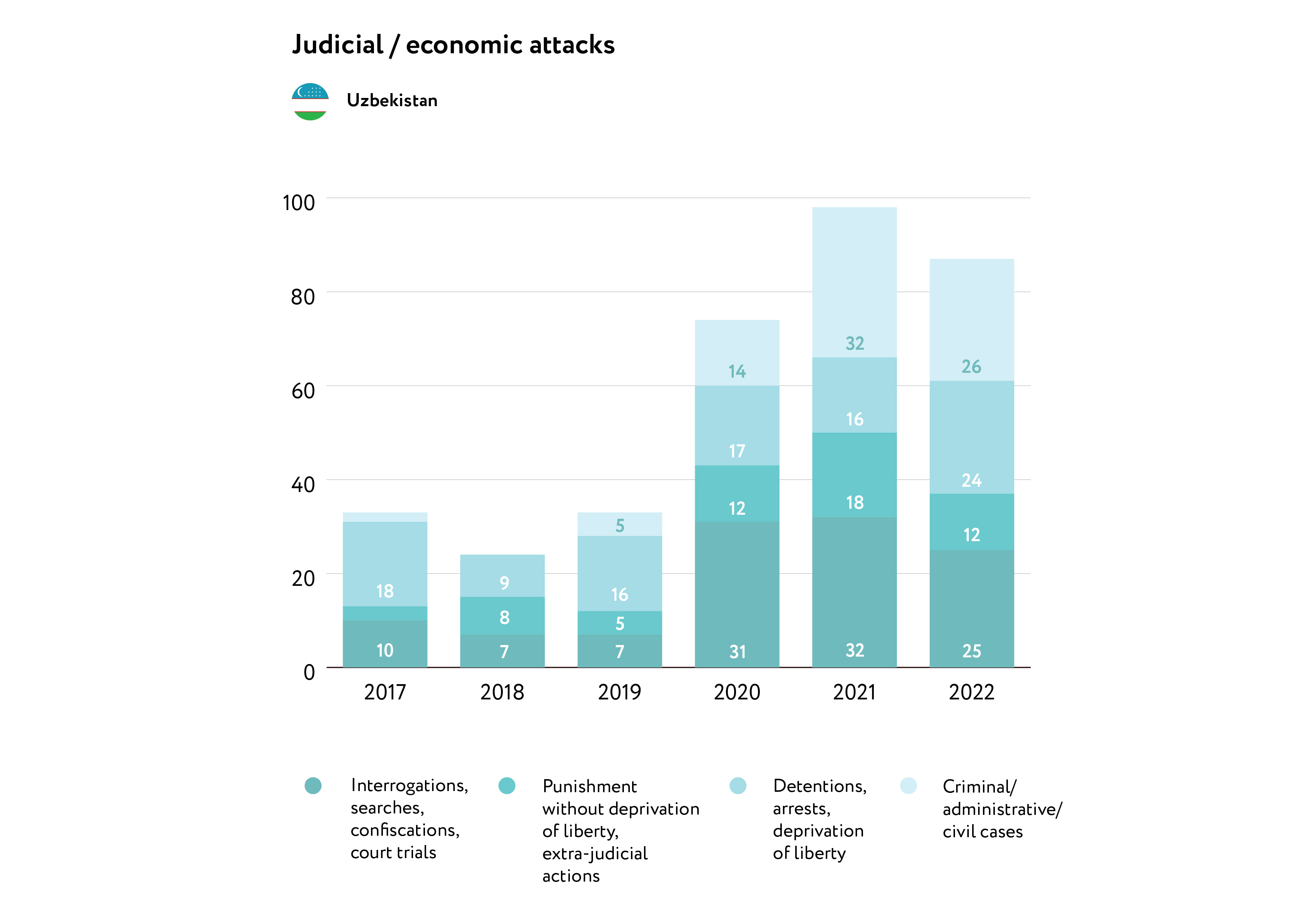

- Attacks via judicial and/or economic means remained the main method of exerting pressure on media workers. The number of such attacks against media workers has tripled since 2017.

- Since 2017, the total number of attacks on journalists and bloggers has more than doubled.

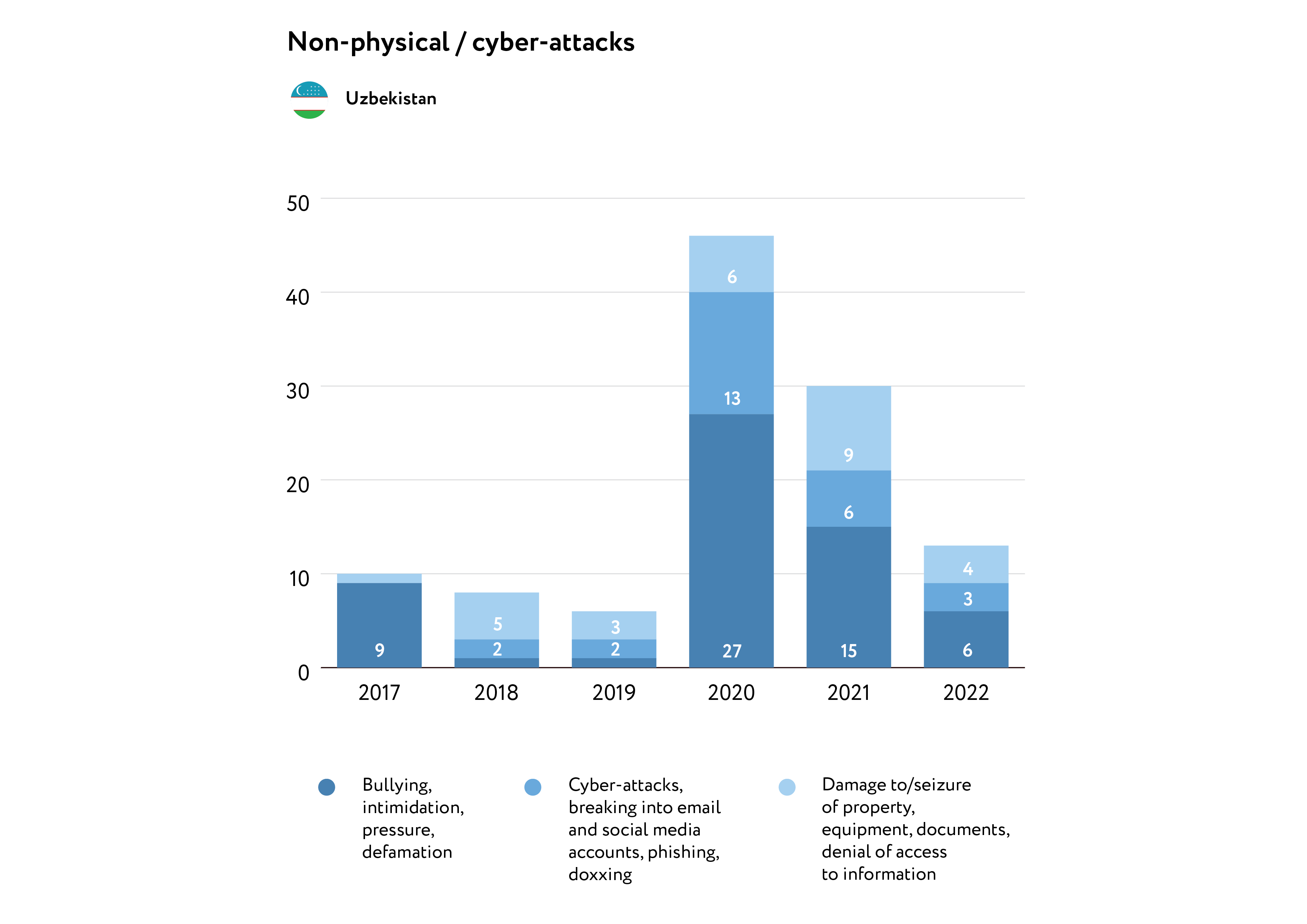

- The number of attacks of a non-physical nature (and/or cyberattacks and threats) decreased from 30 in 2021 to 13 in 2022.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN UZBEKISTAN

The annual Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index for 2022 ranks Uzbekistan 133rd out of 180 countries. In 2021, the country ranked 157th. However, this apparent improvement is due to a change in the ranking’s methodology. State propaganda continues to dominate in Uzbekistan. The government controls both the media and the internet, and suppresses any public expressions of dissenting opinion.

At the end of 2022, 1,962 media outlets were registered in Uzbekistan, 65% of which were non-state media and 677 of which were online publications.

The main political event of 2022 was the series of protests in the Republic of Karakalpakstan, an autonomous area of Uzbekistan. The unrest, which took place from July 1 to July 3, was brutally suppressed by the government. Tensions began to increase on June 25 following the publication of draft constitutional amendments. These included changes to six articles of the constitution (70-75) granting the Republic of Karakalpakstan sovereign status within Uzbekistan, as well as the right to secede from the country if a majority votes in favour of the decision. These changes, which essentially eliminated the sovereign status of the republic, were met with widespread protests.

Residents of Nukus, the capital of the Republic of Karakalpakstan, took to the streets en masse following the arrest of Dauletmurat Tajimuratov, a lawyer and former editor of the newspaper El Khyzmetinde (“In the Service of the People”), on July 1. Other journalists and bloggers were subsequently arrested.

On December 14, the Agency of Information and Mass Communications posted on the Internet details of the draft law on the Information Code. The public was able to post comments until December 29, by which time 80 comments had been posted, and the survey was closed. The bill contained broad provisions to limit information released during investigations and legal proceedings and referenced information that may be considered “offensive” or “demonstrates disrespect for society, the state or state symbols, including obscenity”. The bill also banned the promotion of “propaganda” about same-sex relationships, reinforcing the existing stigma against members of the LGBT community in Uzbekistan. The law, were it to be introduced, would hold internet users and bloggers responsible for reposting “inaccurate information”. The status of this bill remains unknown, but individual aspects of it have already been included in the new edition of the Criminal Code.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

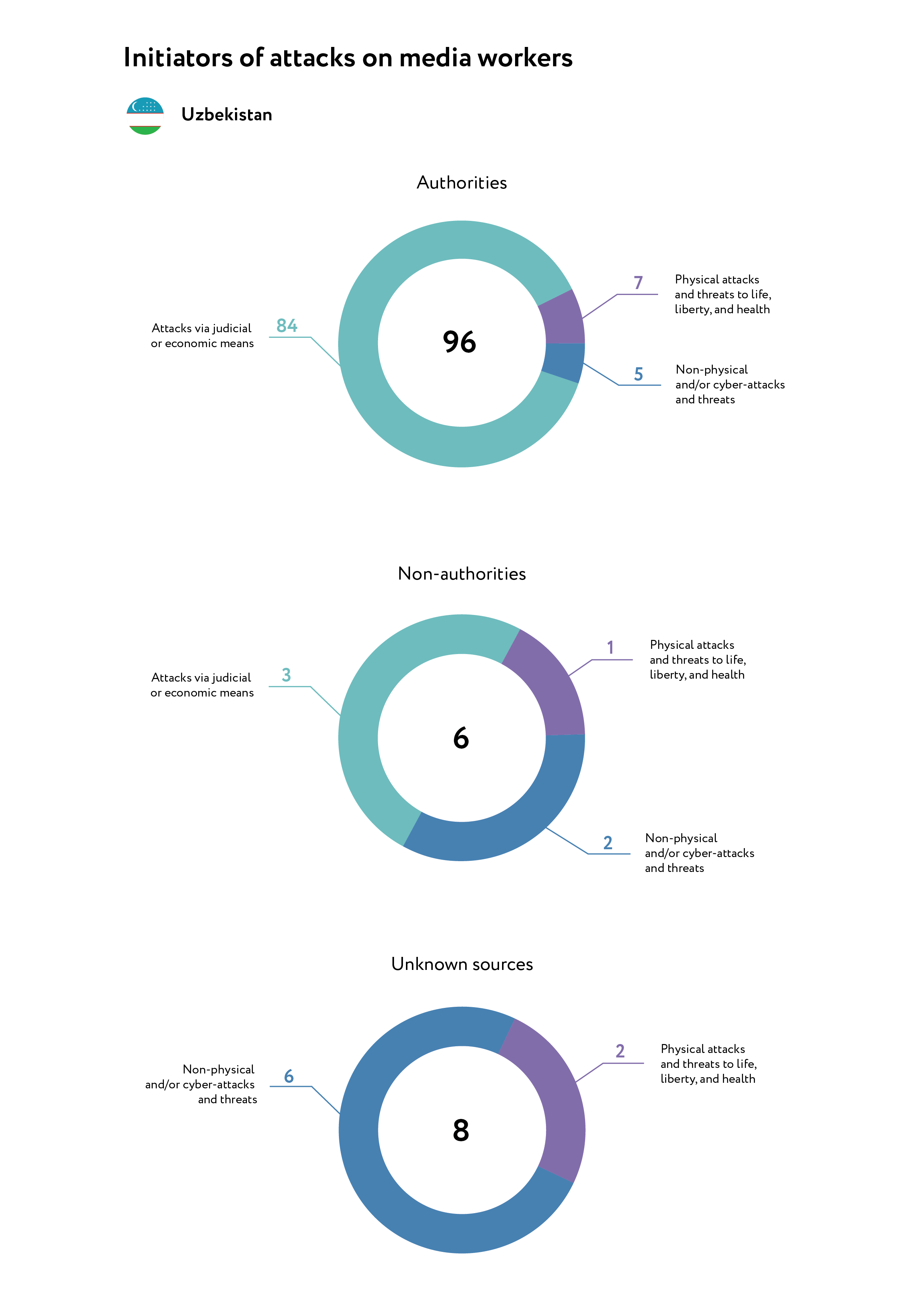

Figure 1 shows a general analysis of the three main categories of attacks/threats against media workers in Uzbekistan. Fewer incidents were recorded in 2022 than in 2021, but compared to 2017, the number of attacks on journalists and bloggers more than doubled. In 87% of cases, these attacks were committed by government officials.

As was the case in previous years, the number of attacks was calculated using open-source information. Media workers, independent journalists and bloggers often remain silent about these attacks due to fear of further harassment by the authorities.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

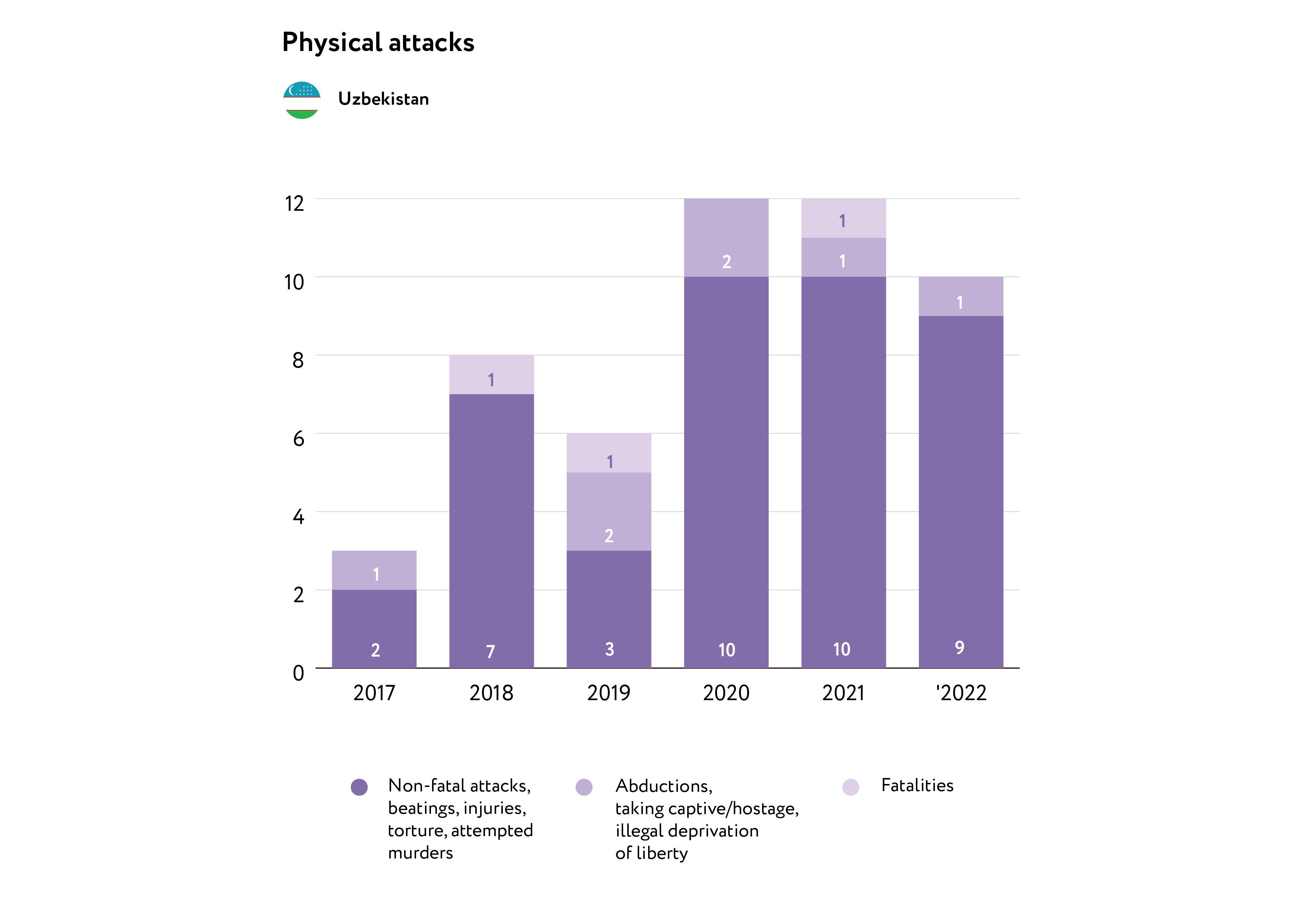

Since 2020, the number of physical attacks has remained the same. In 2022, 10 attacks were recorded, seven of which were committed by government officials. All recorded attacks were non-fatal. It is worth noting that many physical attacks were accompanied by non-physical attacks, including damage to/seizure of property.

One incident of abduction, kidnapping and wrongful imprisonment was recorded.

- On June 26, blogger Kural Rametov posted critical comments on social media about the aforementioned amendments to the constitution, depriving Karakalpakstan of its sovereignty. Shortly after this, he was arrested. According to non-governmental sources, police officers tortured him with electric shocks and left him stranded after removing his clothes. He managed to return home but was immediately re-arrested and was taken to the neighbouring Khorezm region. It is reported that his wife and other family members may have also been detained.

- On December 21, the Tashkent City Internal Affairs Directorate sent Shahida Salomova, administrator for the Telegram channel “Pathanatomy of the country of Uz”, to undergo a mandatory psychiatric examination. The court placed Salomovain in a medical institution. She was detained on December 18 after a tip-off (presumably by 52-year-old blogger Alexey Garshin) to the Central Internal Affairs Directorate. Garshin allegedly requested that legal measures be brought against Salomova for posting slanderous content on social media platforms. Prior to her detention, on December 13, Shahida posted a video on YouTube discussing Alexey Garshin’s work with the Uzbek intelligence service. Salomova was prosecuted under Part 2 of Articles 139 and 140 (“libel in print, including posts online”).

There were several non-fatal physical attacks against media workers carried out by government officials in 2022:

- On June 11, police officers attacked journalists from the Uzbek TV channel Sevimli in front of numerous witnesses. The news programme Zamon reported the attack first, but the post was soon deleted. Prior to this, the victims’ colleagues downloaded the material, published it in Uzbek, and shared it on social media.

- On July 2, Abdimalik Khozhanazarov, editor-in-chief of Akmangit tany (“Dawn of Akmangit”), was hospitalised after being assaulted by police officers. Prosecutors forced him to state, in writing, that his injuries were the result of a fall.

- On July 2 and 4, the former editor-in-chief of the newspaper El Khyzmetinde (“In the Service of the People”), Dauletmurat Tajimuratov, was beaten while being transported to the neighbouring Khorezm region by helicopter. “They put a large key in the palm of my hand, and twisted it like a meat grinder,” he said.

There were also a number of non-fatal attacks committed by unidentified individuals:

- On June 12, blogger Mustafa Tursinbayev was assaulted while investigating the allocation of water resources in the Kanlikul region of Karakalpakstan. Tursinbayev’s social media channels have a total of 146,000 subscribers and followers.

- On December 24, blogger Abdukodir Muminov, who runs the Ko’zgu YouTube channel, which has 227,000 subscribers, was attacked by unidentified individuals, who broke the windows of his car with a bat and assaulted him.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

In 2022, the number of recorded non-physical attacks more than halved, compared to 30 incidents in 2021. This decrease is due to the fact that editors of publications often choose not to disclose cases of threats against media workers. In turn, independent bloggers also often remain silent about the non-physical attacks they face.

Harassment, intimidation, accusations of slander, and threats were the most common methods of exerting pressure on media workers, although the number of such incidents decreased from 15 to 6 in 2022. Examples of such incidents include:

- On January 25, an unidentified person contacted blogger Alisher Saitov, an administrator of the “Voice of Gelsomino” Telegram channel, and asked to meet with him. In a subsequent conversation, he asked Alisher not to write an article about the deputy chairman of the State Security Service, Batyr Tursunov, who is the father of the president’s eldest son-in-law. The blogger considered this to be a threat from the Tursunov family.

- On April 14, the editor-in-chief of Rost24.uz, Anora Sadikova, reported that she had been threatened and was forced to delete a video about entrepreneur Jakhongir Usmanov. Usmanov’s father is the late Mirabror Usmanov, a senator, former deputy trade minister and head of both the Football Federation and the National Olympic Committee. The journalist has since re-posted the video on her Facebook page.

- On May 11, Sharifa Murod (Sharifa Madrakhimova), a journalist for the Buvaida Kuzgusi newspaper, published an appeal from a local farmer to President Mirziyoyev ahead of his arrival in the Fergana region. Following this, Sharifa said she was subjected to pressure from the press secretary of the Buvaida district and the editor-in-chief of the Buvaida Kuzgusi newspaper, Aziza Solieva, who asked her to write and submit a letter of resignation. Shortly after, the journalist reported that the conflict had been resolved, explaining that there had been a “misunderstanding”.

In 2022, three cyberattacks were recorded:

- On June 16, the independent online publication Asiaterra was subjected to a cyberattack and disabled by the host owner. According to editor Alexei Volosevich, the perpetrator of the cyberattack lives in Tashkent. The attack took place, he claims, in response to the site publishing confidential information about the president.

- On June 25, Gazeta.uz was hacked twice in short succession after the publication of an article entitled “Proposals to extend the presidential term to 7 years”, which stated that “Part 2 of Article 90 of the Constitution permits an increase in the presidential term from 5 to 7 years”. The comment attracted an influx of trolls, who aggressively targeted Gazeta.uz. These comments, many of which were copied and pasted, were posted from either identical or similar IP addresses.

- On September 20, Kun.uz journalist Elmurod Ermatov was subjected to abuse online after the publication of an article about the construction of a gas station five meters away from a residential building in Namangan. There was speculation that the owner of the CNG filling station may be a close relative of the governor of the Namangan region, Shavkat Abdurazakov. Anonymous individuals insulted Ermatovand and stated that the publication was “biased” and was “trying to make money”.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

Attacks via judicial and/or economic means continue to be the main method of exerting pressure on media workers in Uzbekistan, most commonly via criminal, administrative and civil cases (26 incidents in 2022). In 96% of cases, these attacks were perpetrated by government officials.

In 2022, there were five criminal/administrative prosecutions for libel and violation of privacy and two cases filed against individuals disseminating “false information”. There were also five cases of prosecution for extremism, connections with terrorists, inciting hatred, treason, and calling for the overthrow of the constitutional order. Three appeals against these charges were unsuccessful:

- On March 4, the Tashkent City Criminal Court upheld the sentence against blogger Miraziz Bazarov for the “slander” of pro-government bloggers, as well as other unnamed individuals. During the deliberation between the parties, Bazarov’slawyer, Sergei Mayorov, reiterated the illegality of the verdict and the absurdity of the charges. He asked that the Mirabad District Court annul the decision and acquit his client. The prosecutor simply argued that the prosecution had proven Bazarov’s guilt. On January 21, Bazarov was sentenced to three years of restricted freedom, including the time he had already spent under house arrest.

- On January 26, a trial in the case against religious blogger Fozilhodzhi Arifkhodjaev concluded in Tashkent. He was found guilty under Paragraph D, Part 3 of Article 244-1 of the Criminal Code (“production, storage, distribution or display of materials that threaten public safety and public order”) and was sentenced to seven years and six months in prison. The trial concerned a conflict between Fozilhodzhi Arifkhodjaev and Abror Abduazimov (also known by his online pseudonym Abror Mukhtor Ali), an employee for the Centre for Islamic Civilization, who also had links with the case against blogger Miraziz Bazarov. Despite the Supreme Court’s decision to allow members of the public to participate in court proceedings in order to ensure transparency, the Tashkent City Court prohibited human rights defenders from attending the trial.

- On April 5, the Judicial Collegium for Criminal Cases considered the case against blogger Otabek Sattoriy. The blogger’s previous sentence was upheld. On May 10, 2021, the court found him guilty of slander and extortion, and sentenced him to six and a half years in prison. On July 15, 2021, representatives from the Samarkand Court of Appeal upheld the sentence.

The main political event of 2022 was the series of protests in the Republic of Karakalpakstan, an autonomous region of Uzbekistan. Some incidents related to the events in Karakalpakstan include:

- The “Constitution of Karakalpakstan” Telegram channel was deleted on June 26, a day after it was set up, at the request of the authorities. Over 100,000 users had subscribed to the channel, calling for mass protests.

- On July 2, the Prosecutor General’s Office announced the arrests of 14 people as part of a preliminary investigation in a criminal case lodged under Part 4 of Article 159 of the Criminal Code (“conspiracy to seize power or overthrow the constitutional order”) in connection with mass unrest in Karakalpakstan. Among those detained was the editor of Makan.uz Lolagul Kallykhanova, who was accused of being a threat to public safety. “She was brought in as a suspect and was procedurally detained,” the supervisory authority reported. Also among the detainees were the editor-in-chief of the newspaper El Khyzmetinde (“In the Service of the People”) Yesimkhan Kanaatov, as well as journalists Mustafa Tursinbaev and Bakhtiyar Kadirbergenov.

On January 31, 2023, the court announced their verdicts on the case regarding the events in Nukus:

- Blogger and founder of the website Ayama.uz Bakhtiyar Kadirbergenov was found guilty under Part 3 of Article 244 (“organising mass riots”) and Paragraph D, Part 3 of Article 277 (“hooliganism associated with disobeying a government representative protecting public order”) and was sentenced to seven years in prison.

- Blogger Azamat Nuratdinov from the Muynak district of Karakalpakstan was found guilty under Part 3 of Article 244 (“organising mass riots”) and Paragraph A, Part 3 of Article 244−1 of the Criminal Code (“production, storage, distribution or display of materials that threaten public safety and public order”) and was sentenced to five years of restricted freedom. This was reduced to four years, five months, and 17 days to account for time served. The judge eventually cancelled these measures against Nuratdinov and released him from custody.

- Journalist and founder of the Makan.uz website Lolagul Kallykhanova was given an eight-year suspended sentence at a trial in Bukhara, with a probationary period of three years. This was reduced to seven years, five months, and six days to account for time served. After the verdict was announced, she was released from custody. Lolagul was found guilty under Part 4 of Article 159 (“conspiracy to seize power or overthrow the constitutional order”), Part 3 of Article 244 (“organising mass riots”) and Paragraphs A, B and D of Article 244-1 (“production, storage, distribution or display of materials that threaten public safety and public order”).

- Blogger Elmurad Odil (Elmurod Odilov) from the Yakkabag district of the Kashkadarya region was found guilty of libel and sentenced to 15 days in prison. On January 30, the blogger reported on problems with electricity at the No.71 family clinic. A few days earlier, Odil accused the Chairman of the Senate, Tanzila Narbayeva, of causing the energy crisis in the country and staged a protest demanding her resignation.

Law enforcement agencies, in an effort to minimise discussions about the war in Ukraine and potential clashes with Russia, carefully monitor publications. There are a number of examples of this:

- On February 26, the founders and managers of the online publication Kun.uz, Umid Shermuhammedov and Makhsud Askarov, were summoned for questioning by the State Security Service. Uzbek security officers claimed that the journalists had “incorrectly” covered the war in Ukraine. During their interrogation, the journalists were told that these events must be covered in a “restrained and neutral manner”. Three employees from the publication were also summoned for questioning; the publication has not disclosed their names. Umid Shermukhammedov subsequently deleted his post about their interrogation by the security services.

- On March 4, the Centre for Mass Communications demanded that independent journalist Marina Kozlova delete an interview with Mikola Doroshenko, the Ambassador of Ukraine to Uzbekistan, “within 24 hours”. The agency allegedly discovered “photos and videos that contradict the requirements of current legislation”. The notice included neither a date nor the signature of the relevant official but presented a list of four laws which Marina could be subject to criminal prosecution for violating. The journalist refused to delete the interview and is prepared to take legal action.

Other incidents recorded in 2022 include:

- On February 3, the Khazarasp district court in the Khorezm region sentenced blogger Sobirzhon Boboniyazov to three years in prison. He is known in the region as an active member of the blogger community. The head of the Ezgulik Human Rights Society, Abdurakhman Tashanov, reported that the online activist was accused of attacking the former leader of the country, Islam Karimov. On April 21, a forensic linguistic examination showed that the blogger’s posts had breached Article 158 of the Criminal Code (“attacks on the President of the Republic of Uzbekistan”). The human rights activist clarified that “according to the indictment, the blogger committed a crime with aggravating circumstances … repeatedly, and while intoxicated”.

- On July 22, bloggers Olimjon Khaidarov and Komiljon Akhmedov from Fergana were sentenced to 15 days of administrative detention on charges of “distributing materials promoting religious hatred” (Article 184-3 of the Code of Administrative Responsibility). According to reports, Komiljon Akhmedov posted a comment on his Facebook page about “an illegal church operating in Kokand”, and Khaidarov reposted the comment. Both bloggers later deleted the posts. Khaidarov maintained his innocence.

- On September 25, journalist Aziz Yusupov, who works closely with human rights organisations, was detained in Fergana and held in detention for three months. Yusupov’s arrest took place shortly before the Human Dimension Conference in Warsaw organised by the Organization for Security and Co-operation (OSCE), suggesting that the authorities wanted to stop Yusupov from delivering a speech calling for “independent information on the human rights situation in Uzbekistan”. Two days after his arrest, on September 27, the Criminal Court in Fergana charged him with possession of narcotic drugs under Part 1 of Article 276 of the Criminal Code and sentenced him to three months in prison.

- On November 11, the Mirabad District Criminal Court of Tashkent sentenced Instagram blogger Sevinch Sadullayeva to five days in prison. The statement (and indeed the accusation) was made by the deputy khokim of Tashkent, Nodira Umarova, who is also the head of the department for family and women. Sadullayevawas was charged under Article 183 of the Code of Administrative Responsibility (“hooliganism”), having allegedly “deliberately ignored the rules of behaviour and violating public order”. The court ignored Article 29 of the same code, according to which women with children under three years of age cannot be sentenced to administrative arrest. Sadullayeva has an 18-month-old daughter.

- On December 8, the deputy editor-in-chief of Oyina.uz, Inobat Akhatova, claimed her mother was interrogated by the internal affairs department of the Narpai district in Samarkand. Law enforcement officers were trying to gather information about the journalist’s social media content. They had Inobat’s contact information but did not contact her, choosing instead to interrogate her elderly mother.

- On December 18, the administrator of the Telegram channel “Pathanatomy of the country of Uz”, Shakhida Salomova, was detained. She was searched and her equipment was confiscated. After Shahida’s arrest, her Telegram channel was deleted. Salomova was prosecuted under Part 2 of Article 139 and 140 (“libel in print, including posts online”). She was sent for a mandatory psychiatric examination on December 21.

ANNEX 1: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (UZBEKISTAN)

- ACCA.media – an independent human rights media project that writes about human rights violations.

- AsiaTerra – an information and analysis website covering Central Asia.

- Centre1.com – an independent media organisation specialising in Central Asian news.

- Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) – an international non-governmental organisation that defends the rights of journalists.

- Eurasianet – an independent news organization that covers news from and about the South Caucasus and Central Asia, providing on-the-ground reporting and critical perspectives on the most important developments in the region.

- Fergana News Agency – a resource covering events in Central Asia.

- Gazeta.uz – a news website specialising in Central Asian news.

- International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) – an international non-profit organisation with its headquarters in Brussels, Belgium. Established in spring 2008.

- Radio Ozodlik – the Uzbek Service of Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty.

- Repost.uz – a news website specialising in Central Asian news.

- Upl.uz – a news website specialising in news about Uzbekistan.

- The Association for Human Rights in Central Asia (AHRCA) – an independent human rights organisation. The initiators behind the founding of the AHRCA were citizens of Central Asian countries who had experienced politically motivated persecution.

- Open-source media in the Uzbek, Russian, and English languages accessible on the internet and social networks.