This article is part of the JFJ Investigative Grant Programme and was originally published on the Global Voices website.

Nearly 80 per cent of killings of Colombian journalists go unpunished, according to Ángela Caro, a lawyer of the Colombian organization Foundation for Press Freedom (FLIP, for its acronym in Spanish). This is not a surprise in a country with a long history of violence against journalists.

FLIP registered 161 murders of journalists from 1977 to 2000. Only one case resulted in convictions of everyone involved in the crime. In just four cases, the mastermind was sentenced, and in 29, the perpetrator of the crimes. Unfortunately, 127 are in total impunity and 92 have been archived by Colombia’s prosecutor offices.

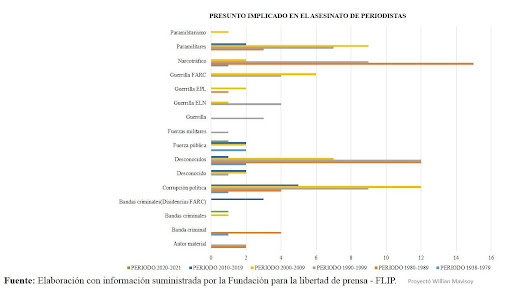

These 161 journalists killed were victims of paramilitary groups, criminal groups, drug dealers, members of the public security and state forces, and guerrillas such as the FARC, ELN, and EPL. Sixty-one of these communicators worked for print media, 64 for radio stations, and 16 for television.

Relatives of victims found justice on only a few occasions. The case of Orlando Sierra, a writer at La Patria regional newspaper based in Manizales who was killed in 2002, is one of those cases. It took 17 years to convict the mastermind of this crime, Ferney Tapasco. This is the only case in which the whole criminal chain — the hitman, two collaborators, and the intellectual author — was convicted.

However, the judicial decision left his colleagues with a sour taste. Fernando Ramírez told Global Voices:

This case was resolved with the same evidence that they had at least 10 years before. If justice is a form of dissuasion to prevent people from committing crimes, impunity in Colombia is almost an incentive, because it is really difficult that someone is convicted even though they are guilty.

When a judge declares the murder of a journalist as a crime against humanity, which means that it cannot be time-barred, the case is taken on with renewed vigor. One such case was the 1986 killing of Guillermo Cano, editor at the Colombian newspaper El Espectador who had denounced the role of drug traffickers in politics. However, Caro from FLIP told Global Voices:

There are no efforts from the nation’s Public Prosecutor Office to get results. Guillermo Cano’s case was declared a crime against humanity in 2010, but there is still impunity.

Reporting from the trenches of life

According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Colombia ranks 134 in the list of worst countries for journalists. The best for press freedom are Norway, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and Costa Rica.

Impunity for crimes against journalists is not an exclusive problem to Colombia. Brazil, Honduras, and Ecuador also have high rates of impunity. Barely one in 10 murders of journalists are prosecuted in Latin America, explains Ernst Sagaga, Head of Human Rights and Safety at the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), in an interview with Global Voices.

From 2011 to 2020, Mexico, Colombia, Brazil, and Honduras were some of the most dangerous countries for journalists, states RSF. Most of the journalists killed lived far away from big cities, worked in precarious conditions often for various media outlets, and reported about their communities and state agents.

During the 1980s, violence against journalists was rampant. The crisis of security was such that IFJ opened a solidarity center in Bogotá to offer security for journalists while lobbying for their protection with national authorities.

Sagaga added:

Indeed, [the government of] Colombia adopted a protection program for journalists under threat, which is still running today. But the program has a mixed record, especially after journalists lost trust in it because of strong evidence of collusion between security forces running the program and those targeting journalists.

Despite the fact the cruelest years passed for Colombia, danger did not disappear and journalists still need protection.

Elusive Justice for Journalists

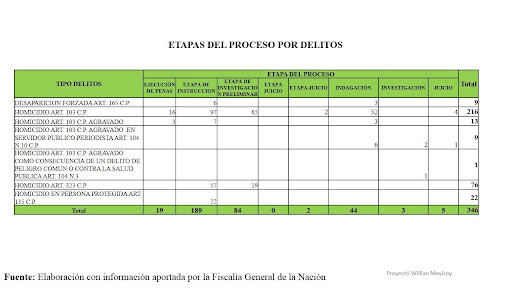

According to information from the Public Prosecutor’s Office obtained through a records request, the agency counted 346 crimes committed from 1980 to 2020, whereby journalists were victims of homicide, femicide, homicide of protected persons (referring to homicides of people under government protection), and forced disappearance.

International organizations suggest strategies to curb violence against journalists in Colombia. Sagaga says:

Authorities must publicly denounce violence on journalists, investigate, and prosecute them in a credible manner to punish those responsible and deter future similar crimes.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) believes that Colombia should focus on staffing local investigation offices and promoting transparency. Natalie Southwick, Program Coordinator Central and South America & the Caribbean at CPJ, told Global Voices:

While Colombia’s (admittedly far from perfect) protection mechanism has been a model for other countries across the region, Colombia lags behind other countries like Mexico or Guatemala that have created national- or state-level prosecutor’s offices that specialize in investigating cases of violence against journalists and press freedom violations. These offices are not a solution to impunity on their own but allocating staff and resources specifically to address these crimes allows for more opportunity to investigate such cases and identify the perpetrators and sends a clear public message that the state is prioritizing these cases, which in itself can help discourage more violence against the press. Greater transparency in official processes and regular public updates on the investigations into these cases would also help encourage greater accountability from the state institutions responsible for these investigations.

*This is one of five stories about crimes against journalists in Colombia, an initiative supported by the Justice for Journalists Foundation (JFJ), a London-based non-governmental organization. JFJ funds journalistic investigations into violent crimes against media workers and helps professional and citizen journalists to mitigate their risks.