ARMENIA

AUTHOR OF THE REPORT: The Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression (CPFE)

PHOTO: The Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression (CPFE)

1/ KEY FINDINGS

227 cases of attacks/threats against journalists and the media in Armenia were identified and analysed in the course of the research for 2021. Data for the study were collected using open source content analysis in Armenian, English, and Russian. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 1.

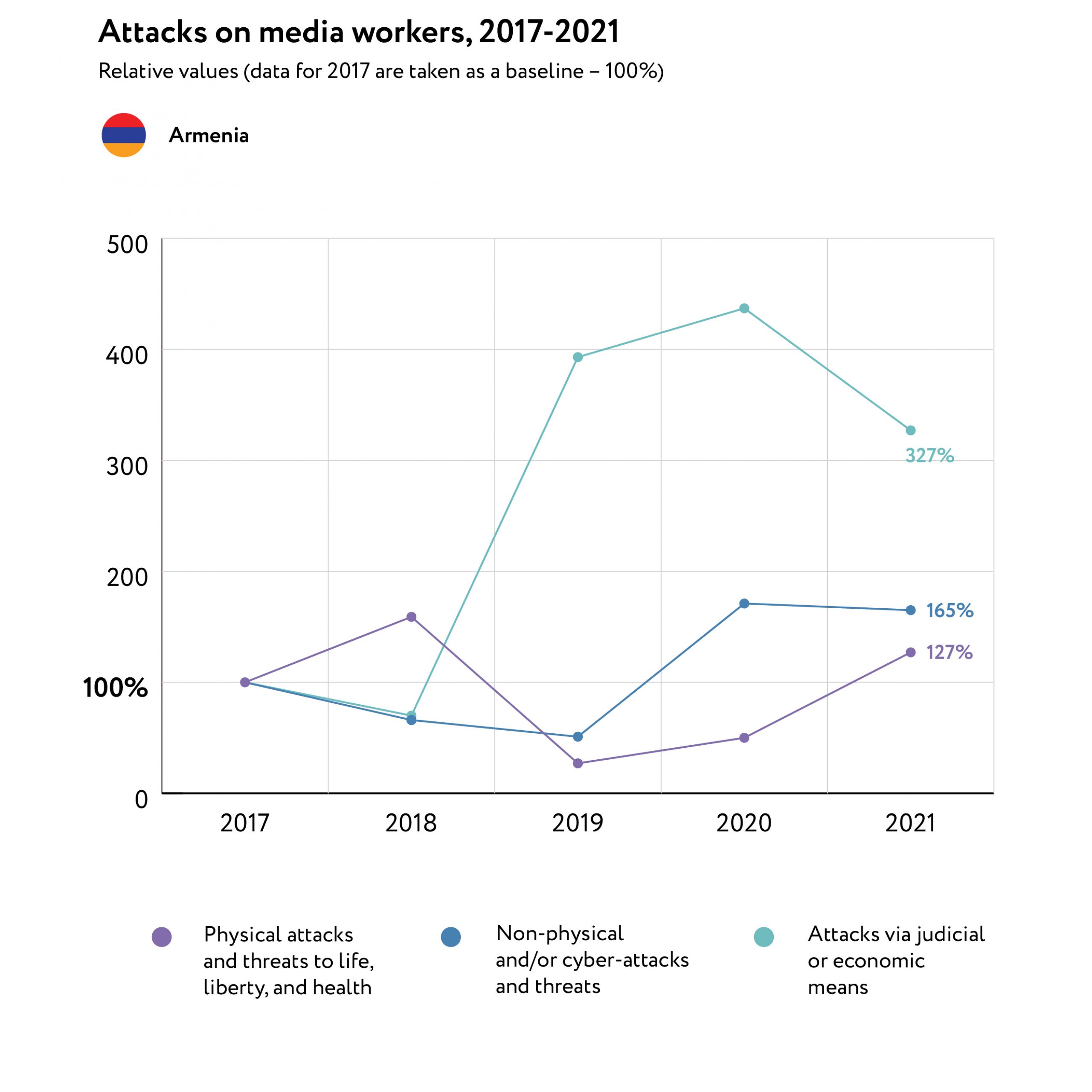

- In 2021, the total number of attacks on media workers and the media decreased by more than 12 percent compared to the previous year.

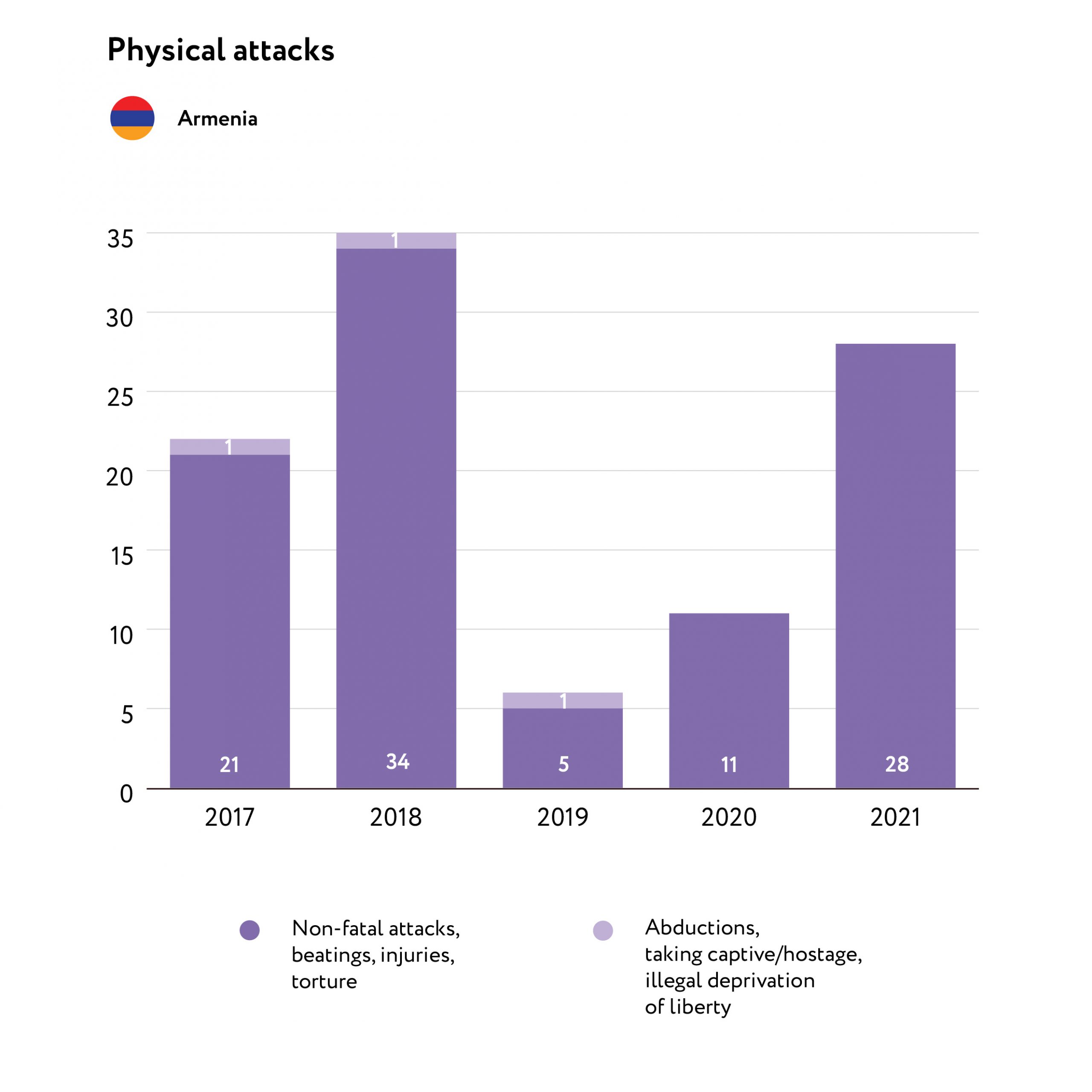

- Of significant concern, however, is the three-fold increase in the number of physical attacks on media workers. The majority (57%) of the attacks on journalists and videographers were committed during coverage of rallies and demonstrations during an acute socio-political crisis, as well as during the early parliamentary election campaigns.

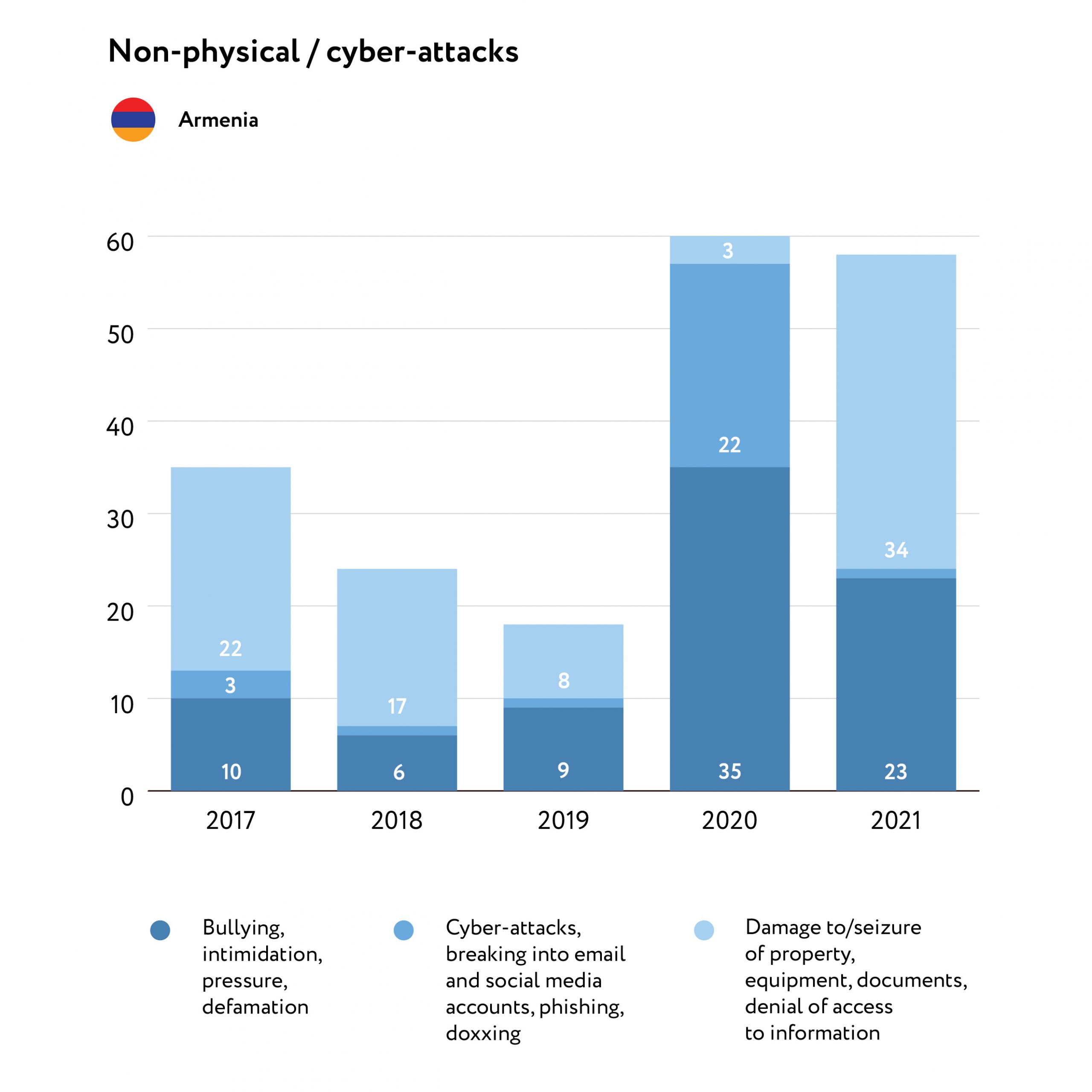

- The number of attacks and threats of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks, remained at the same level as the previous year. 63 percent of these were committed by government officials.

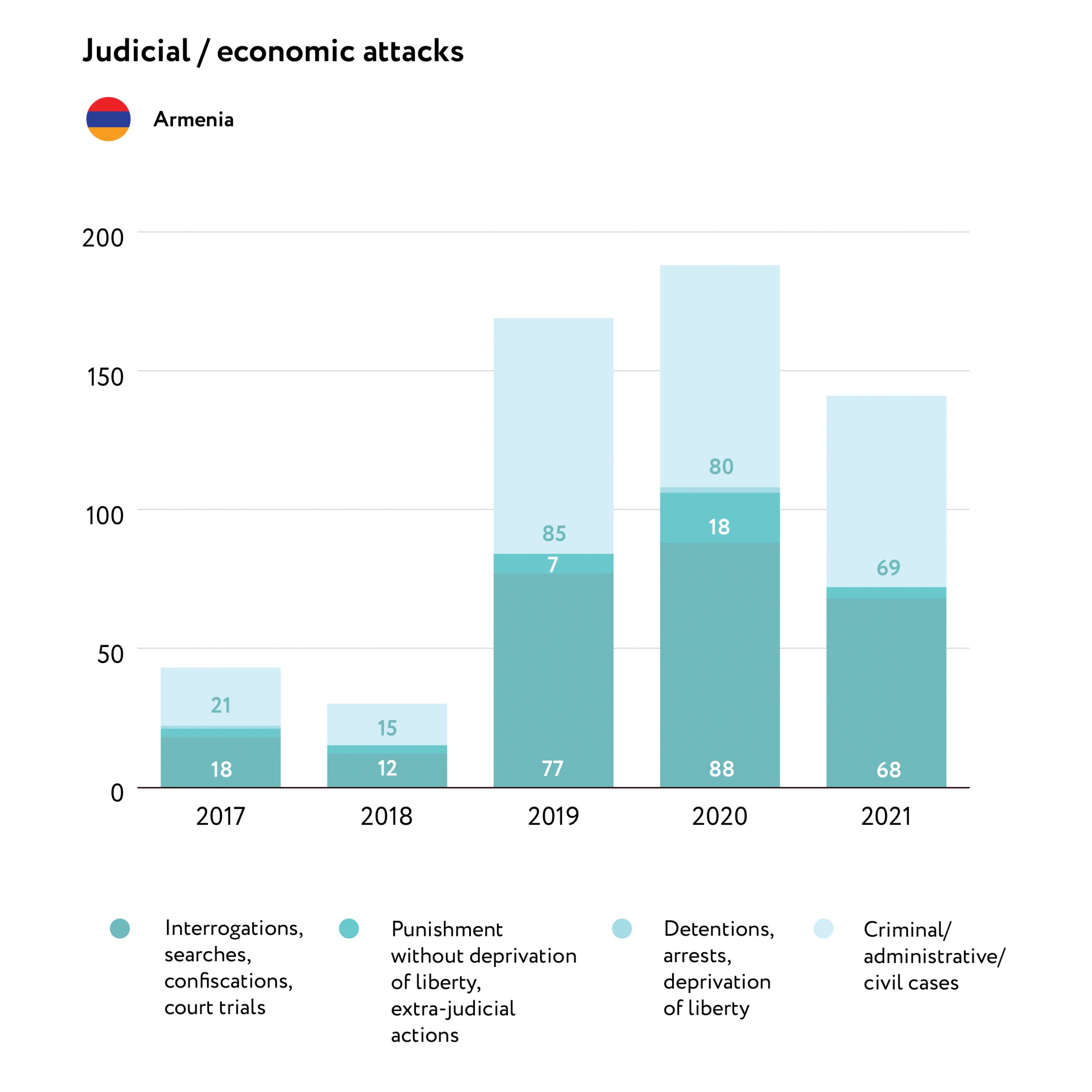

- In 2021, legal methods of exerting pressure on journalists and the media remained the primary means of attack. Over the year, 68 lawsuits were filed against media organisations and workers for alleged insults and defamation.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN ARMENIA

In 2021, Armenia was ranked 63rd out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ (RSF) annual World Press Freedom Index. In the rankings for 2022, Armenia rose to 51st place. RSF noted that “despite the pluralistic environment, the media remains polarised. The country is facing an unprecedented level of disinformation and hate speech, especially regarding the territorial dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh.”

2021 proved to be an extremely difficult and arduous year for the Armenian media. This was primarily as a result of the deep socio-political crisis caused by the country’s defeat in the 44-day Nagorno-Karabakh war. Thousands of protests and marches took place across the country, organised by the 17-party opposition coalition. This united opposition was comprised of those removed from power during the 2018 Velvet Revolution. They accused Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan of being a traitor and demanded his resignation. This opposition aimed to create a transitional government, headed by a candidate who would then announce early parliamentary elections.

Pashinyan’s supporters saw these demands as an attempt by the former ruling elite to unconstitutionally regain power and reinstate their corrupt regime. As a result, this opposition failed to unite sufficient popular support to allow them to overthrow the current government. In addition to this, Pashinyan held a series of rallies, both in the capital and elsewhere in the country, demonstrating the extent of his popular support. To overcome this political crisis, the Prime Minister held lengthy and complicated talks with the parliamentary opposition. On March 18, it was announced that an agreement had been reached to hold early elections to the National Assembly of Armenia on June 20, 2021. This, in turn, led to a reduction in tensions.

Against the backdrop of such a combative political situation, the work of the media was significantly hampered. Journalists from media outlets which, in the opinion of the opposition, supported the current government, were subjected to physical attacks and insults while covering the protests. Additionally, attacks against members of the opposition media took place during rallies and marches of Pashinyan’s supporters. A number of cases of pressure being exerted on journalists in parliament were also recorded.

Acute socio-political issues increased the polarisation in the media sphere. The media more often than not aligned itself within the country’s political system. Much of the media’s work appeared to serve the interests of specific political parties and leaders, as well as discrediting their opponents through propaganda. As a result, public interests were either pushed into the background or ignored entirely. The media audience became a hostage in the country’s information war.

This was evident during the early parliamentary elections. According to independent observers, this election campaign was the “dirtiest” in independent Armenian history, both in terms of the propaganda used to discredit opponents and in terms of the rhetoric employed. Observers noted all standards of decency were flouted and direct insults and obscenities common. The electorate had a front row seat to this, not only during pre-election meetings and rallies, but also via the media and social networks.

For the most part, the media did not objectively cover the elections, instead acting as an instrument of pre-election campaigns. Disinformation, manipulation, insults, defamation and hate speech were already widespread. However, these soon reached unprecedented levels. As a result, in his June 11 statement, Prime Minister Pashinyan said, “This country’s media has turned into a garbage dump,” and that “people are acting more like hitmen than journalists.”

This, gave rise to another trend: an increased distrust and intolerance towards individual media organisations and journalists, not only in political circles but amongst ordinary citizens. As was the case during the mass protests, numerous cases were recorded in which media workers affiliated with specific parties and blocs faced harassment, insults, threats, and violence while covering election events organised by representatives of other political groups.

The difficult situation in the media prompted the authorities to more actively promote legislative initiatives, both new and previously proposed. These, according to their backers, would help improve media professionalism. For the most part, these legislative proposals, far from solving the problems that had arisen, instead posed a serious threat to freedom of speech and contradicted international norms, including the European Convention and the European Court of Human Rights.

The second half of the year was a period of relative political calm. Nevertheless, after the elections, in which Nikol Pashinyan’s Civil Contract party won by a landslide, the media and social networks remained the main weapon in the fierce struggle for power, allowing the opposition to broadcast their hatred and hostility.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

Generally, in 2021, a high level of risk remained for those working in the media. Despite the fact that the total number of attacks on media workers decreased by 12 percent compared to 2020, one of the main categories, “physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health”, saw a three-fold increase. The other two categories of violations – “non-physical and/or cyberattacks and threats” and “attacks via judicial and/or economic means”—saw a decrease of 5 percent and 25 percent, respectively. As was the case in previous years, the vast majority of cases of legal pressure on journalists and the media, more than 95 percent, came in the form of court cases, which were brought against media outlets and individual journalists for insults, defamation, and reputational damage. The total number of attacks has doubled since 2017.

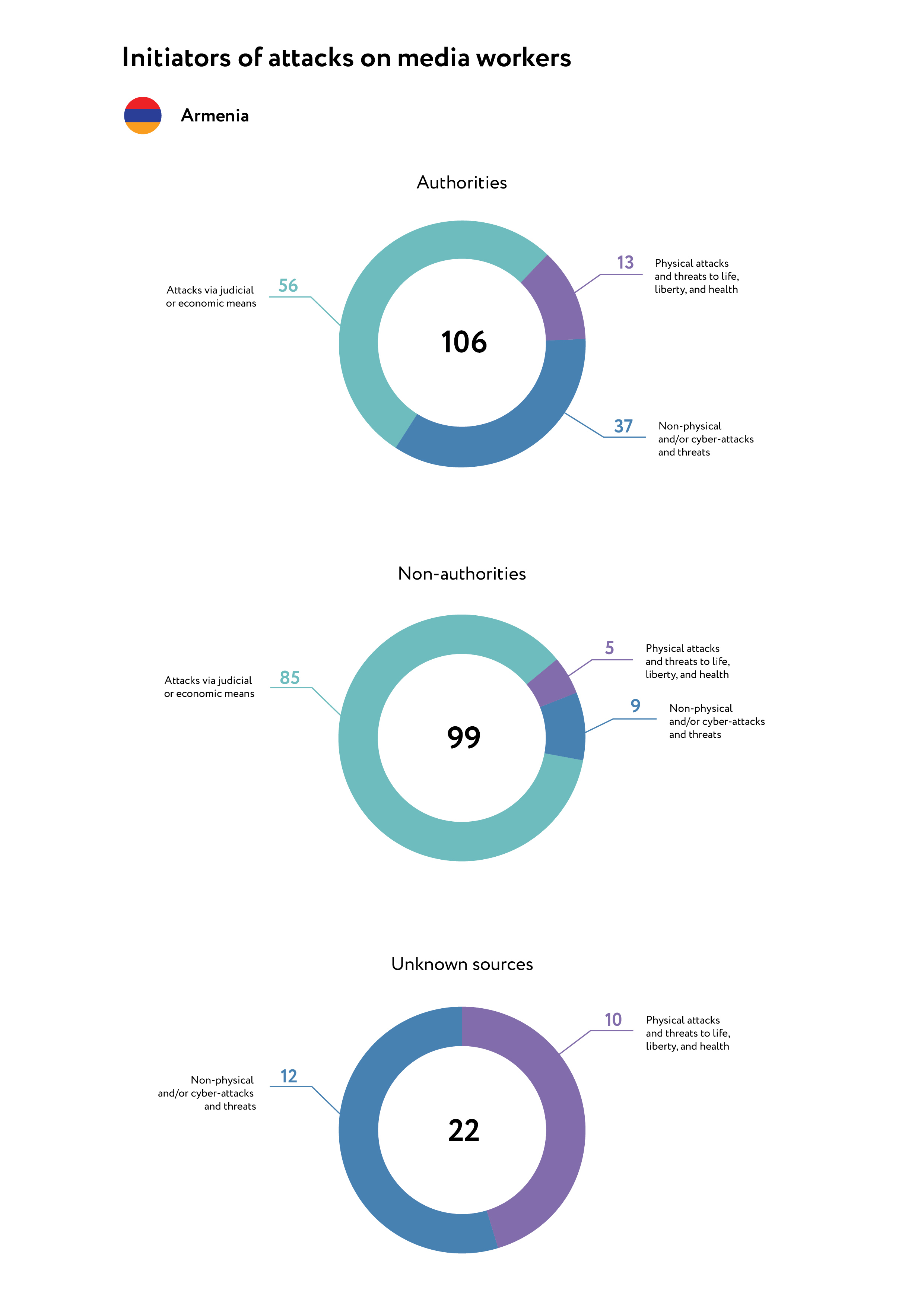

In 2021, a total of 227 incidents were recorded. Of these, 106 were committed by government officials, 99 by individuals who were not representatives of the authorities, and 22 from unknown persons.

The following factors were primarily responsible for the numerous violations of the rights of journalists and the media:

- The acute socio-political crisis, which erupted after the country’s defeat in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, continued into the first half of 2021. In this context, intolerance towards journalists, especially during coverage of mass protests, demonstrations and processions was high;

- An extremely tough political struggle during the early parliamentary elections, as well as the aggressive behaviour of government officials, opposition forces and their supporters against media workers affiliated with opposing parties;

- Increasing political polarisation of the media to the detriment of professional journalism and public interests.

In 2021, two incidents related to pressure on media workers under the pretext of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions were also recorded:

- On January 19, a correspondent for Factor.am stated that the Supreme Judicial Council’s decision to restrict journalists’ access to court rooms was an obstruction. The journalist was not allowed to attend the court session. According to official information, this was due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- On February 9, police sent a notice to the News.am editorial office demanding the removal of two publications about COVID-19, since, according to the authorities, they violated restrictions introduced in a March 16 decree introducing a state of emergency due to the spread of COVID-19.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

All 28 of the physical attacks against media workers recorded in 2021 fall under the subcategory of “non-fatal attacks” (beating, causing injury, torture). 16 (57%) of these incidents occurred during media workers’ coverage of mass protests, rallies, and demonstrations, as well as at politicians’ meetings with voters during early parliamentary elections. A further ten assaults were by security services in relation to access restrictions imposed by the leadership of the National Assembly on accredited journalists and videographers. Two incidents took place, in different circumstances, as a result of conflicts between a media worker and an official.

Of the 28 physical attacks against journalists and videographers, 13 were committed by representatives of the authorities, five by non-government officials, and ten by unknown persons.

The following physical attacks caused the most public outcry:

- On February 23, during a mass protest organised by opposition forces in Yerevan, a group of demonstrators attacked two Radio Azatutyun employees, correspondent Artak Khulyan and videographer Karen Chilingaryan, who were covering the event. The participants of the march insulted, threatened and kicked the two journalists, and damaged their video equipment. A criminal case was initiated as a result and sent to the Investigative Committee. However, as of August 16, the investigation was put on hold due to an inability to identify the attackers.

- On March 18, in a cafe in Yerevan, the Minister of High-Tech Industry, Hakob Arshakyan, was physically violent towards Irakanum.am editor Paylak Fahradyan. The journalist, having noticed the high-ranking official, approached him and asked what he was doing in the cafe during working hours. According to media publications, the conversation became heated and the minister hit the journalist several times, as well as damaged his computer and phone. The Prosecutor’s Office referred the case to the Special Investigation Service to clarify the details of the incident. However, the Special Investigation Service closed the case due to a “lack of evidence.”

- On May 9, during a rally of the “Armenia” pre-election bloc, which was headed up by the second President of the Republic of Armenia, Robert Kocharyan, members of a Civic.am film crew, journalist Vladimir Hakobyan and videographer Petros Petrosyan, were injured on Yerevan’s Freedom Square. Kocharyan’s supporters, having spotted the journalists, threatened them with violence, pushed them, and prevented them from filming. The journalists were forced to flee the area. Police officers on the square intervened, but no charges were brought against any of the attackers.

- On June 14, during a pre-election meeting between voters and Acting Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, a group of participants were aggressive towards Yerevan.today correspondent Suzi Badoyan. Badoyan was pushed, and attempts were made to snatch the microphone from her hands. On November 18, a criminal case pertaining to this event was closed due to a “lack of evidence of the suspect’s identities.”

- On August 25, violent arguments broke out in the National Assembly, which escalated into a mass brawl between deputies of the ruling and two opposition factions. Security officers broke into the press box and forcibly removed ten journalists and videographers from the premises, demanding that they stop filming. Media workers faced the same ban at the entrance to the parliament’s session hall.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

In 2021, 58 incidents of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats were recorded, 5 per cent fewer than in 2020. The following types of attacks took place: illegal obstruction of journalistic activities or refusing access to information (26 cases); harassment, intimidation, threats of violence and death, including online threats (23 cases); damage/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials (8 cases) and one incident related to a hacking attack on the media.

25 of the 26 cases of illegal obstruction of journalistic activities, and deprivation of access to information; were committed by government officials. Cases include the following:

- On June 20, the day of the parliamentary elections, at polling station 29/45, where ex-president Serzh Sargsyan was supposed to vote, the secretary of the election commission tried to impede the work of the Public Television of Armenia journalist David Machkalyan and 168.am journalist Henrikh Sargsyan. He tried to prevent them from filming, claiming they did not have the correct accreditation. However, following intervention from the Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression, the incident was resolved, and the operators were able to continue their work.

- On August 5, Panorama.am photojournalist Lilian Galstyan was prevented from passing through a checkpoint into the National Assembly building. It later transpired that she was deprived of accreditation and the opportunity to report on the Parliament’s proceedings.

- During the elections on October 17, Aravot.am correspondent Satenik Hovsepyan was approached by Civil Contract party representative Vanush Piloyan near polling station 38/9. Piloyan rudely demanded that they stop filming, as he did not want to be in the shot. The journalist objected, arguing that she was filming a public building and if someone did not want to be in the frame, they could leave. Piloyan threatened to sue if he appeared in the video, after which he demanded to be shown the footage.

Media workers were often subjected to harassment, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including online threats. These attacks were committed by government officials in seven cases, by non-state actors in eight cases, and by unknown persons in another eight cases.

Examples include:

- On May 12, Andranik Kocharyan, chairman of the Standing Committee on Defense and Security, representing the ruling My Step alliance, insulted Aravot.am news correspondent Hripsime Jebejyan. During a discussion about the state of the country, a high-ranking official began to ask about the journalist’s personal and family life.

- On December 8, independent journalist Tatul Hakobyan, while on a lecture tour for the Armenian diaspora, as well as students, entrepreneurs, and public figures in the United States; reported that he received threats via Facebook and other social networks, including death threats. The threats stemmed from his statement that “for me, Armenia is where the Armenian soldier stands.”

In contrast to 2020, during which there were 22 hacking attacks on dozens of media outlets, only one such incident was recorded in 2021:

- On November 16, the information site Armtimes.com was a victim of a hacking attempt. The website’s work was quickly restored after only a few hours.

A different situation can be seen in the subcategory “damage to/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials.” In 2020 only one such incident was recorded, however in 2021 there were eight. Of these, five were committed by government officials, while three were committed by unknown persons.

These attacks include the following:

- On January 13, in the National Assembly, deputy of the ruling My Step alliance, Hayk Sargsyan, refused to answer questions from Yerevan.today correspondent Suzi Badoyan. He proceeded to push her and snatch her microphone, which he took to his office. The microphone was only returned after persistent demands from Badoyan and other parliamentary correspondents.

- On April 22, during an opposition rally in front of the General Prosecutor’s Office, Yerkir Media videographer Paruyr Nersisyan fell and injured his leg during a stampede. His camera was also damaged.

- On June 3, Hraparak newspaper reporter Anush Dashtents was attacked in the centre of Yerevan. The journalist noticed National Assembly deputy Hayk Sargsyan standing by the campaign headquarters of the ruling Civil Contract party, so she approached him to ask a question. The MP snatched Dashtents’s phone and drove off, stating that he would not return the device until she “came to her senses.” Sargsyan soon returned the phone to her, via his associates. However, it had been unlocked and the video materials on it had been deleted. The Special Investigation Service refused to open a criminal case “due to the lack of evidence.”

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

In 2021, there were 68 of lawsuits demanding civil liability for defamation, insults, and damage to reputation, down 12 per cent compared to 2020. As was the case in previous years, however, these legal actions remained the most common method of exerting pressure on journalists and media organisations in Armenia.

In 27 cases, the instigators of these trials were initiated by state actors.

Examples of civil legal action against journalists in 2021 include:

- On May 13, Deputy Speaker of the Parliament, Alen Simonyan, filed a lawsuit with the Yerevan Court of General Jurisdiction against journalist Ani Gevorgyan, demanding that she publicly refute statements which Simonyan considered to be slanderous. The lawsuit stemmed from a speech by the journalist on April 16 in the Ayeli press club. She accused Simonyan of organising a campaign against her, accompanied by threats and insults.

- On August 2, the Armenian National Interests Fund (ANIF) filed a lawsuit with the Yerevan Court of General Jurisdiction against both Hraparak Daily Newspaper LLC and journalist Suzan Simonyan, demanding a retraction of allegedly slanderous information, as well as compensation for the damage caused to their business reputation. The basis for the lawsuit was a Hraparak.am publication criticising ANIF’s head, David Papazyan.

- On September 24, the former head of the Special Investigation Service and Chairman of the Anti-Corruption Committee, Sasun Khachatryan, filed a lawsuit with the Yerevan Court of General Jurisdiction against the editorial office of the newspaper Zhoghovurd, demanding it retracts slanderous statements and compensates for the damage caused his honour and dignity. The basis for the lawsuit was an article published in the newspaper and on the Armlur.am website, stating that Khachatryan withheld information about his real estate and finances.

- On December 10, Hayk Sargsyan, a member of the National Assembly, filed a lawsuit with the Yerevan Court of General Jurisdiction against the Zhoghovurd newspaper, demanding that it compensate for alleged damage caused to his honour, dignity, and business reputation. The basis for the lawsuit was an article published in the newspaper and on the website Armlur.am, casting doubt on the whereabouts of Sargsyan on the day of the high-profile murder of a former deputy.

In 41 cases, lawsuits were initiated by non-state actors.

- On January 26, the office of the Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly in Vanadzor filed a lawsuit with the Yerevan Court of General Jurisdiction against the Antifake.am news site, demanding that it retract slanderous statements and compensate for damage. The basis for the lawsuit was an article entitled, “How much money the NGOs operating in Armenia received for assisting in the surrender of Artsakh.” The article mentioned several organisations, including the Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly.

- On April 19, businessman Khachatur Sukiasyan and his affiliated enterprise Mega Trade LLC, filed 12 lawsuits with the Yerevan Court of General Jurisdiction against Yerkir.am, News.AM, Asekose.am, Blog.168.am, Yerevan.Today, ArmDay.am and Pastinfo.am, demanding compensation for the publishing of slanderous information. The lawsuits were as a result of articles which claimed that the low-quality fuel imported by Sukiasyan caused cars to malfunction.

- On October 4, businessman Petros Tovmasyan filed a lawsuit with the Yerevan Court of General Jurisdiction against Civic.am, demanding that it retract slanderous statements and pay compensation. The basis for the lawsuit was material published on September 1, claiming that the businessman used a tax evasion scheme, registering himself as the sole employee of the beer factory.

In 2021, one incident related to dismissal/involuntary dismissal/forced retirement was recorded:

- On March 16, Public Television of Armenia correspondent Hrachya Papinyan reported that he had been fired. The channel directors claimed that the journalist published false information on Facebook and discredited the authorities.

In addition to the violation of journalists’ and media workers’ rights, a number of new laws and by-laws, which pose a threat to freedom of speech and contradict international norms, are cause for particular concern. On March 24, 2021, Parliament introduced amendments to the Civil Code, whereby the maximum financial compensation for insult and slander was tripled to three million dram (about US 6,000) and six million dram (about US 12,000), respectively. On August 30, these new amendments came into force. Criminal liability was introduced for so-called “grave insults”, for example the public use of obscenity, which includes potential prison sentences. Given both insult and slander were decriminalised in 2010, this decision by the authorities was regarded as regressive and sharply criticised by both the journalistic community in Armenia and international organisations.

Amendments and additions to the Law “On Mass Communication”, adopted by Parliament on December 10, drew similar reactions. These complaints are primarily related to the conditions of journalists’ accreditation, as well as the suspension and deprivation of accreditation.

GEORGIA

AUTHOR OF THE REPORT: Oleg Panfilov, Georgian journalist, commentator and writer

PHOTO: Nikoloz Urushadze

1/ KEY FINDINGS

In Georgia, 302 cases of attacks/threats against professional and citizen media workers and editorial offices of both traditional and online publications were identified and analysed in the course of the research for 2021. Data for the study were collected using open source content analysis in Russian, Georgian and English. This report also includes unpublished data obtained via expert interviews. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 2.

- Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health remained the primary method of pressure on journalists and media workers in 2021.

- For the first time in 20 years, two deaths related to the professional activities of a journalist/blogger were recorded: Alexander Lashkarava, a videographer for the Pirveli television channel, and Nika Kvaratskhelia, founder of the Feedc geolocation platform.

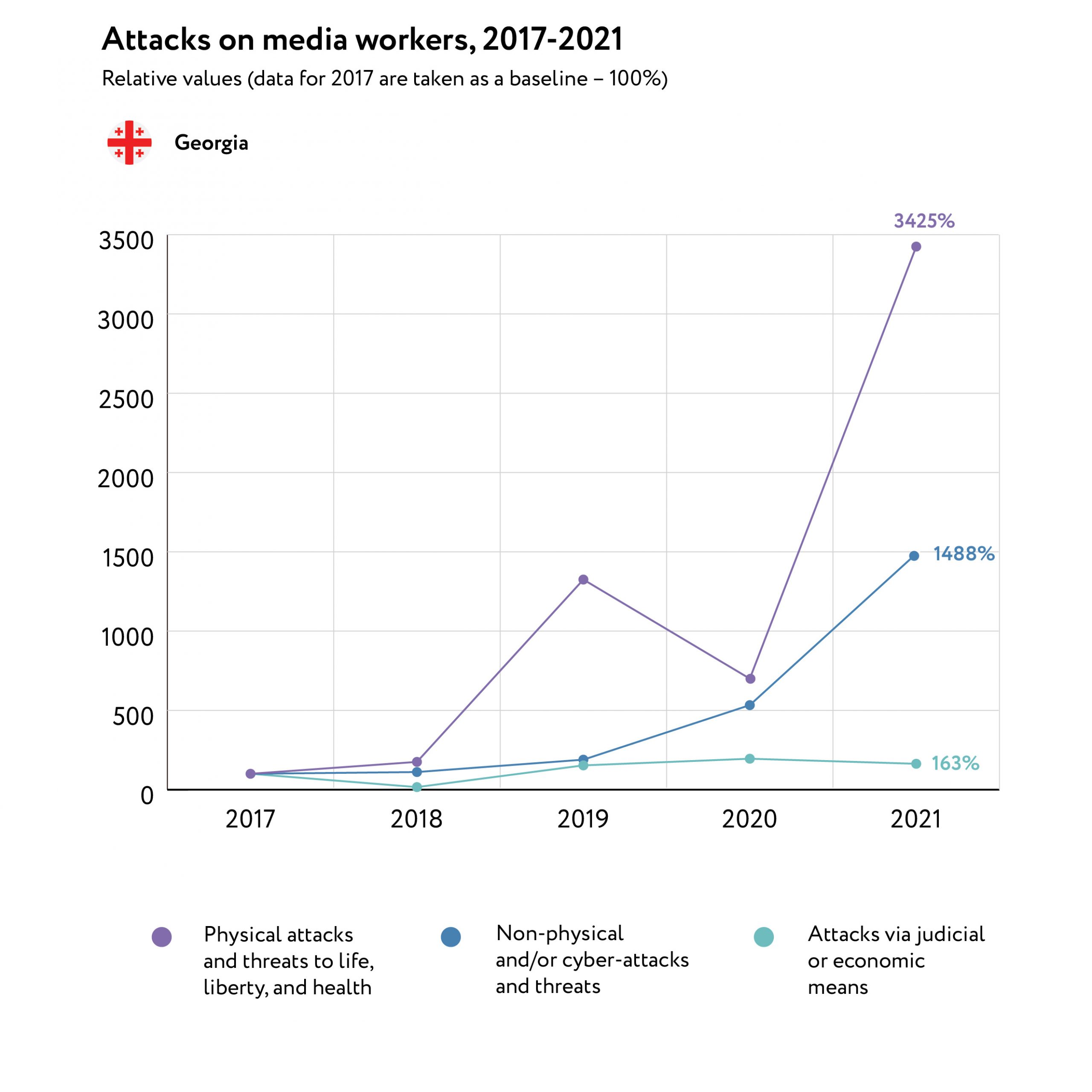

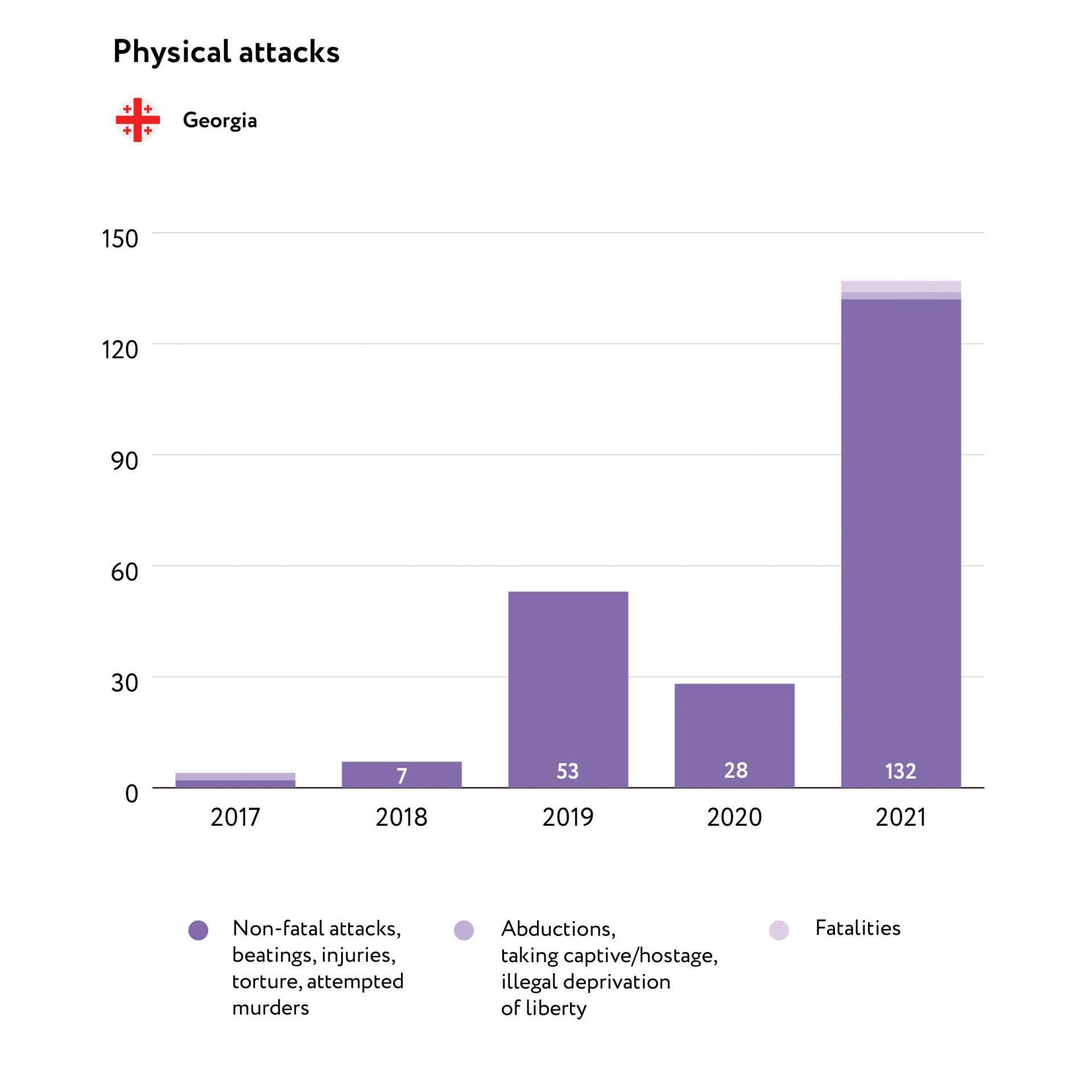

- In comparison to the previous few decades, 2021 was a record year in terms of the number of physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health (137), as well as attacks and threats of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks (133).

- On July 5, 54 journalists, videographers and photographers were assaulted and seriously injured by a crowd of anti-gay protesters at the Tbilisi Pride and March for Dignity. Physical attacks were accompanied by attacks of a non-physical nature: damage/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment and/or documents. Most cases of attacks on journalists during demonstrations were abetted by the weakness, or complete absence, of protection from the police.

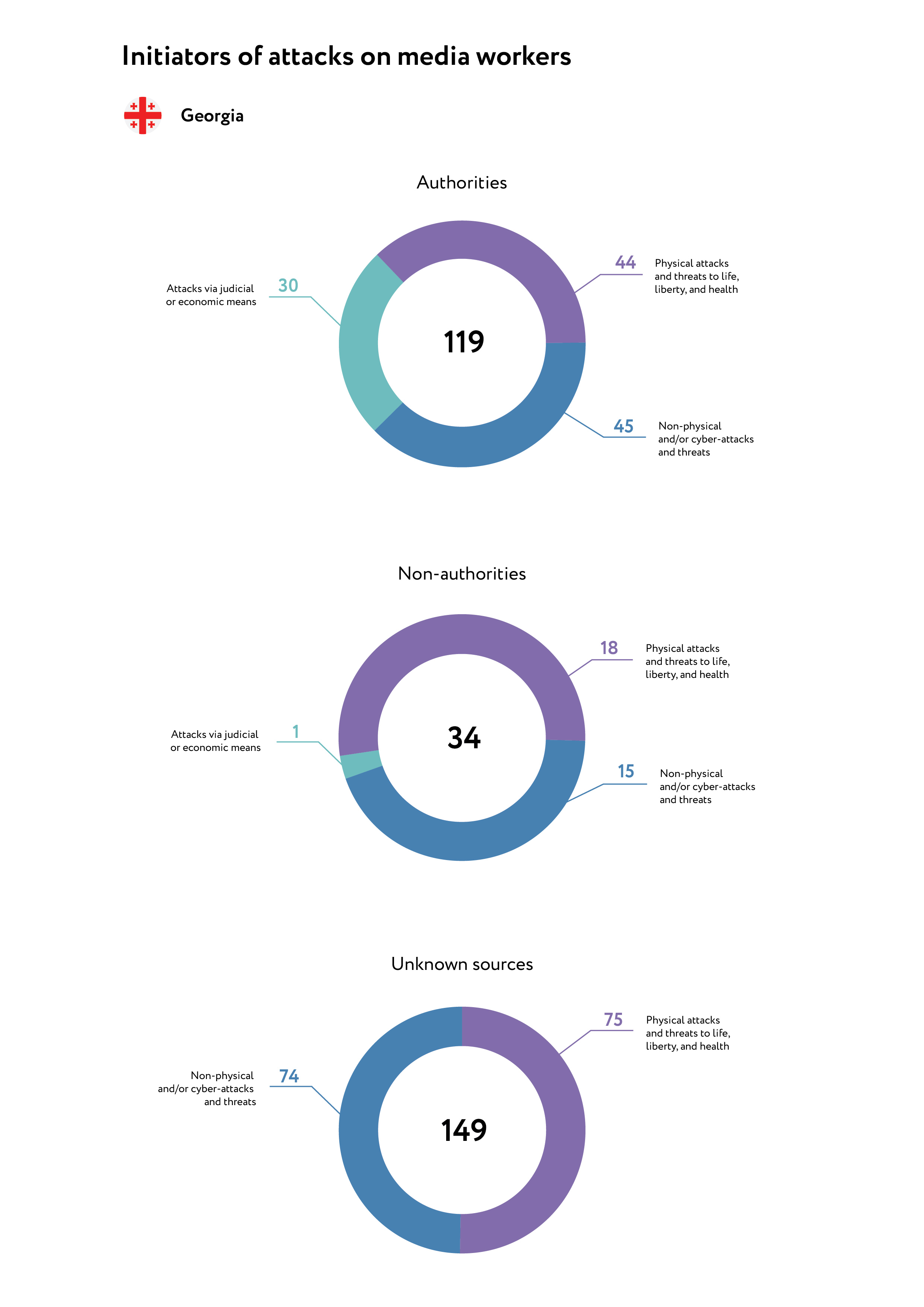

- 39% of attacks were committed by government officials (119 out of 302 incidents).

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN GEORGIA

According to a study by the British analytical company Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), Georgia’s score on the Democracy Index has worsened since 2020.

In 2021, Georgia ranked 60th out of 180 countries in terms of press freedom in the annual rating from Reporters Without Borders. In 2022, it dropped to 89th place as a result of the unprecedented number of physical attacks on media workers.

According to research from DFRLab, 3 million out of 3.7 million people (79%) in Georgia have access to the internet. 96% of Georgian internet users use Facebook more than any other social media, where one can also find accounts for all the main TV channels and information sites. As a result, Facebook is often used to spread disinformation, and discredit journalists and opposition media.

In 2021, Facebook announced the banning of dozens of the aforementioned accounts. 23 accounts, 12 groups and 11 Instagram accounts “aimed at a domestic audience” were banned. The decision was made based on analysis of a report by the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. Facebook’s investigation linked these pages and accounts to the pro-government nationalist organisation Georgian March and its youth wing.

The main source of information for the country’s population is still television, which is regulated by the Georgian National Communications Commission, in accordance with the Law on Electronic Communications (2005). As of the start of 2021, 128 television channels and radio stations were registered in Georgia. For the most part, they are included in cable television packages and offer entertainment programs and films. Of all the media outlets, only two receive state funding: Public Broadcasting (who have two television channels and one radio station) and the Parliamentary Bulletin, which publishes laws.

Channels generally fall into one of two groups: Pro-government channels (such as Imedi, Rustavi-2 and Maestro), or opposition channels such as Mtavari Arkhi, Formula and Pirveli. This divide can also be seen in regional television channels.

The Obieqtivi television channel falls into its own category. The channel is owned by the founders of the pro-Russian Alliance of Patriots of Georgia party and have a stable audience of approximately 3% of the population.

On July 17, 2020, the Georgian parliament adopted amendments allowing the National Communications Commission to appoint, for a period of two years, a “special manager” for electronic communications network operators, i.e., broadcasters that violate the commission’s orders. This manager has the ability to both hire and fire employees, enter into and terminate agreements, as well as overrule decisions from directors, the board of trustees and shareholders. The authorities continue to use this as a way of exerting pressure on opposition channels. In January, the Georgian PEN Centre and several NGOs condemned the Commission’s decision to punish Mtavari Arkhi in a joint statement. Formula (another opposition channel) was also subject to persecution.

In February, the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics noted “an increase in negative assessments of media activities by politicians and attempts to restrict their freedom of expression.” Their statement cites the first vice-speaker of the parliament, Gia Volski, who claimed that “journalists are planning some kind of conspiracy, disinformation, and sabotage.” According to the Charter of Journalistic Ethics, such anti-media rhetoric from officials may contribute to violence against journalists.

Journalists from several television channels and media NGOs signed a joint manifesto, which states: “In 2020-2021, the media environment in Georgia has deteriorated significantly. Verbal or physical attacks on journalists have become more frequent. The state does not ensure the safety of journalists. Representatives of the ruling party respond to critical questions by using the language of hatred, aggression, and boycotts. The state propaganda machine has labelled the media as its political opponents and is fuelling intolerance against them. In a politically polarised society, this attitude towards the media encourages new attacks. There are politically motivated lawsuits against the media. The broadcast regulator has been politicised and is trying to introduce censorship.” In December 2021, Ombudsman Nino Lomjaria described the media situation as follows: “… dozens of cases of physical attacks on opposition media representatives have been recorded, including during the pre-election period. A cynical attitude and statements aimed at discrediting these individuals and organisations have become common practice. <…>On July 5, 2021, 45 journalists and videographers were victims of attacks by the opponents of Tbilisi Pride. Unfortunately, despite the violence that took place on July 5, the Prosecutor’s Office of Georgia did not prosecute any of the individuals responsible for organising and encouraging the violence, despite the assessment of the Ombudsman.”

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

Since 2017, the number of attacks on journalists and media workers in Georgia has grown constantly. Over the course of five years, the number of attacks has increased 15 times as a result of an increase in attacks of a physical and non-physical nature.

In 2021, 119 of the 302 recorded attacks were committed by government officials. As was the case in 2020, the main targets of these attacks were the opposition aligned television channels: Mtavari Arkhi, Formula and Pirveli. As local government elections approached, tensions escalated, with NDI and IRI polling data suggesting that the coalition of opposition parties was well ahead of the ruling Georgian Dream party.

In 2021, 2 attacks were recorded related to pressure on journalists under the pretext of the COVID-19 pandemic:

- On February 9, by order of the Chairman of the Parliament, Archil Talakvadze, Mtavari Arkhi journalist Mariam Geguchadze was denied entry to Parliament. Quarantine measures were cited as the reason for this refusal.

- On December 6, Imedi host Naniko Khazaradze was fired due to her refusal to get vaccinated against COVID-19, despite vaccination being voluntary in Georgia.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

In 2021, 137 cases of physical attacks on journalists were recorded. Two of these attacks led to the death of a videographer and a blogger.

- On July 11, Lekso (Alexander) Lashkarava, a 37-year-old videographer for Pirveli, died having been severely beaten by anti-LGBT extremists on July 5.

- On September 16, in the centre of Tbilisi, Feedc founder Nika (Nikoloz) Kvaratskhelia, was fatally wounded by a firearm. He was shot eight times in the chest, back and legs. Doctors were unable to save him. Kvaratskhelia, a 22-year-old IT specialist, created Feedc, which provides access to a variety of information and educational programs.

In addition to this, one case of sudden unexplained death was recorded:

- On July 30, the body of Azerbaijani blogger Huseyn Bakixanov was found in Tbilisi. He died in unknown circumstances. According to unofficial data, Bakixanov’s body was found in his apartment. Those close to him believe that he was pushed from a height, after which his body was returned to the apartment. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Bakixanov jumped from the 7th floor of the “Rooms” Hotel. This theory of suicide was confirmed by officials at the hotel. According to the hotel’s lawyer, Kakhaber Tsereteli, Bakixanov got a job with them and, while being shown around the building, jumped off the roof in front of two people.

Cases of physical violence against journalists can be divided into two groups.

- Attacks committed by individuals who are not directly connected to the authorities: for example, guards of private establishment or ideological supporters of the authorities. During such attacks, police often do not intervene.

- On March 8, seven journalists were injured by police and priests in Samegrelo. During a meeting of the Chkondideli diocese, during which two priests were removed from the church, a spontaneous action of parishioners began. The priests and police began to push the journalists off the premises. As a result, the railing of the second-floor balcony broke, and the journalists fell from a four metre height. Several people were sent to the hospital with various injuries, including: Ema Gogokhia (journalist for Mtavari Arkhi), Iago Vekua (videographer for the Formula channel), Papuna Shushaniya (journalist for the Pirveli channel), David Kodzharia (videographer for the Rustavi-2 channel, whose arm was broken), Aleko Khazalia (videographer for the Pirveli channel), Soso Khoperia (a correspondent for the POSTV channel), and Zviad Ablotia channel operator, Mtavari Arkhi.

- The extremist organisations “Georgian March” and “Alt-Info” took part in the mass assault of journalists on June 5, the day of the planned LGBT pride event. On July 5, 54 media workers (journalists, videographers, and photojournalists) were attacked in Tbilisi by participants of a homophobic rally. Journalists from various media outlets were attacked, in front of priests and police. Reporters were assaulted, microphones and mobile phones snatched from them, cameras were stolen, and photographers’ equipment was smashed. The police, in almost all cases, failed to protect the journalists.

- On October 2, the voting day for the first round of elections to local self-government bodies, seven journalists were attacked by official observers from the ruling Georgian Dream party: in Tbilisi, at polling station No.4, a film crew from the Pirveli channel (correspondent Ina Tsartsidze and videographer Vazha Tsereteli); in Batumi – the film crew from Pirveli (correspondent Tamta Dolendzhashvili and videographer Giorgo Kokhodze); in Telavi, Pirveli journalist Giorgi Khukhia; in Rustavi – a film crew from the Mtavari Arkhi channel (correspondent Ninutsa Kekelia and cameraman David Badagadze).

- On October 30, the voting day for the second round of elections to local self-government bodies, several journalists were attacked by observers from the Georgian Dream. In Kutaisi, TV Media Centre journalist Giga Gelkhviidze was assaulted. Meanwhile, in Senaki, Mtavari Arkhi correspondent Ema Gogokhia and videographer Zviad Ablotia were also assaulted. Nano Chakvetadze, a journalist from the Formula television channel, was attacked in Martvili; Tamar Tediashvili, also from Formula, was attacked in Gonio (in the Autonomous Republic of Adjara); Irakli Bakhtadze, a correspondent from Mtavari Arkhi channel, was attacked in Poti; and On.ge correspondent Izabel Modebadze was attacked in Kutaisi. In Telavi (Kakheti region), an unknown Georgian Dream supporter insulted and assaulted Formula correspondent Tiko Eradze, knocking the microphone out of her hands. In Zemo Meskheti (Imereti region), Formula correspondent Lika Lezhava was assaulted. From October 29 to 30, 11 journalists were attacked.

- Media workers were targeted by the police or government officials while performing their professional duties, often with the use of special equipment.

- On July 12, four journalists were attacked by police during a protest near the Georgian Dream party’s central office: Mtavari Arkhi correspondent Nene Dalakishvili, Kavkasia TV director Nino Dzhangirashvili, Mtavari Arkhi journalist Beka Korshiya as well as Liberali journalist (and First Channel host) Irakli Absandze.

- On November 17, Pirveli correspondent Mariam Makasarashvili was attacked by Tbilisi Mayor Kakha Kaladze’s guards of when attempting to ask him a question. The mayor’s bodyguard agressively shoved the journalist away.

- On November 29, during a protest dispersal in front of the Tbilisi City Court, where the trial of ex-president Mikheil Saakashvili was being held, Kavkasia TV videographer Niko Kokaia was injured. Polive deliberately and repeatedly used pepper spray on the journalist, as a result of which he lost consciousness. Givi Mchedlishvili, a videographer from Kavkasia TV, was also attacked. Police demanded that the journalist stop filming and threw him off the vantage point, where he was filming the protest.

- On December 17, correspondents from the Mautskebeli agency, Giorgi Arobelidze and Rati Ratiani, were physically assaulted in a police station. The journalists were near a bar, where the police were detaining someone. After questioning the reasons for the detention, the police seized the journalists, took them to the police station and assaulted them.

2021 also saw a geographic spread of physical attacks. In previous years, the majority of attacks took place in Tbilisi, however in 2021, they could be seen all across the country: In Tskneti, Marneuli, Mestia, Martvili, Kutaisi, Davidgaredji, Udabno, Vani, Dmanisi, Abastumani, Tsintskaro, Senaki, Aspindza, Ponichala, Kareli, Batumi, Marani, Samtredia, Zemo Meskheti, Telavi, Poti and Gonio.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

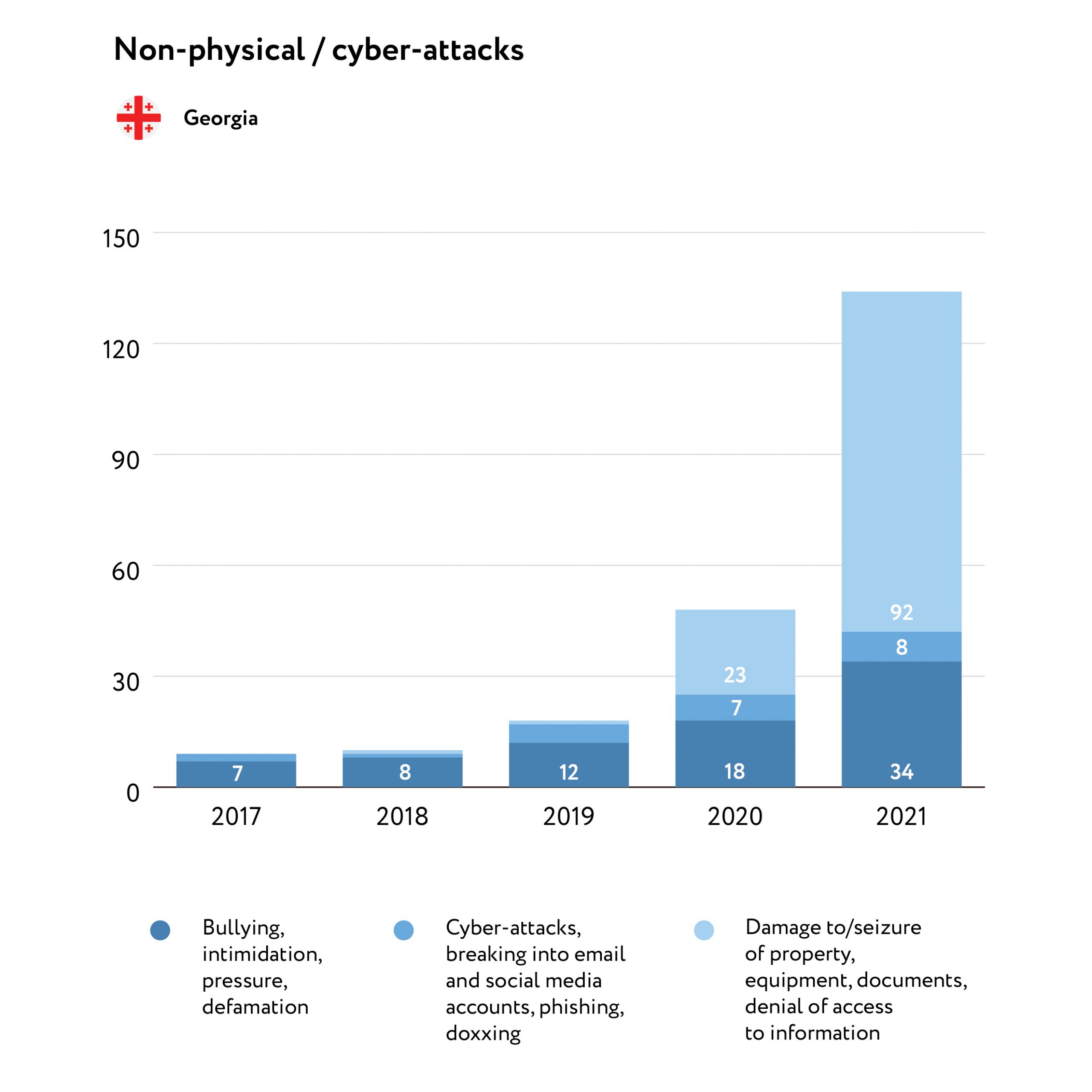

In 2021, 134 incidents were recorded under the category “attacks and threats of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks”, three times more than in 2019. The vast majority of attacks took place as part of the large-scale assaults on journalists on July 5, as well as during the election campaign in October. The following were documented in 2021:

- 21 cases of harassment, intimidation, pressure and threats of violence and death, including online threats;

- 16 cases of illegal obstruction of journalistic activities, and/or deprivation of access to information;

- 8 cases of bugging or surveillance without court permission;

- 5 cases of discrediting and spreading slander against a media outlet/worker.

- On April 4, in the village of Rioni (Imereti region), police officers prevented film crews from the television channels Formula, Pirveli, Mtavari Arkhi and Rustavi 2 from entering the village. This lasted for about two hours, during which time they were forbidden to film a report about a murder. Only after the journalists contacted the Ministry of Internal Affairs, were they allowed to perform their professional duties.

- On July 15, Irakli Kobakhidze, chairman of the Georgian Dream party and former speaker of parliament, said that the Mtavari Arkhi, Formula and Pirveli TV channels were “under investigation” due to undeclared funds. He did not provide evidence, but simply referred to his sources.

- On November 12, a Mtavari Arkhi film crew (correspondent Nino Zhizhiashvili and videographer Ilia Ratiani) were insulted, harassed, and threatened by relatives of Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili while filming an investigation into the clan system in the government. While working on the report, the journalists were followed by a car, from which threats and insults could be heard.

- On November 22, journalists from Mtavari Arkhi and Pirveli, as well as journalists from the Netgazeti website, were denied entry to a briefing headed by Minister of Culture Thea Tsulukiani. Representatives from other media outlets participated in the briefing.

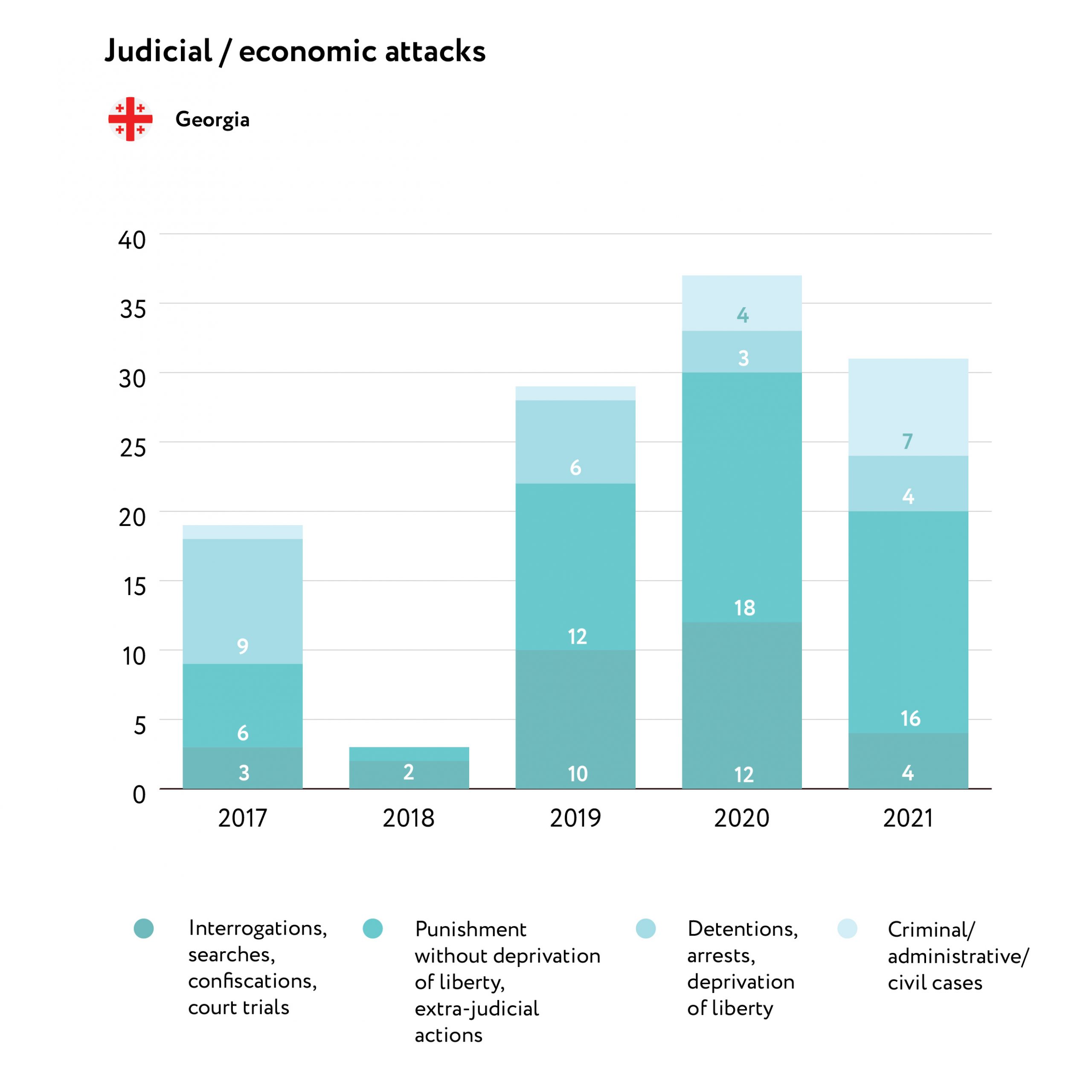

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

The number of attacks via judicial and/or economic means decreased slightly in 2021. 31 attacks were recorded, 6 fewer than in 2020. The most common methods of exerting pressure on journalists included: warnings, conversations, questioning and other non-procedural actions (7); persecution for insulting honour, dignity, and reputation; violations of privacy (4); bans on entering the country; and denial or withdrawal of a visa and/or accreditation (4).

Of the 31 attacks against journalists and media outlets using judicial and/or economic means, 24 were committed in Tbilisi, three in Sukhumi, two in Batumi, and one in both Poti and Kutaisi.

- On May 16, the Tbilisi City Court sentenced Nika Gvaramia, director general of Mtavari Arkhi, to three years and six months in prison on charges of embezzlement. He was taken into custody.

- On August 10, Georgian Public Broadcasting unilaterally terminated host Irakli Absandze’s employment contract. The journalist was detained on July 12, at a rally in front of the Georgian Dream party’s office, where a protest was held following the death of Pirveli TV videographer Lekso Lashkarava. Absandze suggests that his dismissal is due to pressure from the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

- On August 12, Guram Rogava, host of an analytical program on Rustavi 2, said in an interview with Radio Liberty, that he was pressured into resigning following the clashes on July 5. He said that “certain” political leaders demanded he be taken off air.

In 2021, there were four cases of civil prosecution of journalists for insults to honour, dignity and reputation, as well as violations of privacy, and two cases of criminal prosecution for insults:

- On February 4, Poti city police officer Gela Kvashilavi demanded an apology from the Pirveli TV channel following a story about drug crime. He believes that the journalists discredited his honour, dignity, and working reputation; and demanded compensation for moral damage.

- On October 20, Kutaisi mayoral candidate Ioseb Khakhaleishvili, of the Georgian Dream party, filed a lawsuit against Mtavari Arkhi, its CEO Nika Gvaramia, and journalist Eka Gagua. The basis for the lawsuit was the assertion that Khakhaleishvili is “an agent of the State Security Service of Georgia.”

- On December 2, Abkhazia’s General Prosecutor’s Office opened a criminal case against bloggers Lolita Khalvash, Lolita Brandzia and “other unspecified individuals.” This was due to posts on Facebook between August 24 and October 10, 2021, which “undermine the professional reputation, and discredit the honour and dignity of the President, Prime Minister, Minister of the Interior, deputies of the People’s Assembly, the Prosecutor General and other officials.”

Four foreign journalists were denied entry to Georgia:

- On October 27, Ukrainian journalists Dmitry Gordon and Alesia Batsman were told, upon their arrival at Tbilisi International Airport, that they were banned from entering the country. No official explanation was given. The following day, Georgian Dream party chairman Irakli Kobakhidze, said that “the Georgian authorities will not allow anyone to put on a show in the country.”

- On November 18, independent Ukrainian journalist Volodymyr Zolkin was denied entry, again without explanation.

- On November 19, Ukrainian journalist, and editor-in-chief of InfoCar.ua, Pavlo Kashchuk, was denied entry to the country. No explanation was given.

MOLDOVA

AUTHOR OF THE REPORT: Association of Independent Press of Moldova

PHOTO: Sergiu Baldin, Nordnews.md

1/ KEY FINDINGS

68 cases of attacks/threats against professional and citizen media workers and editorial offices of both traditional and online publications in Moldova were identified and analysed in the course of the research. The total number of attacks on journalists in 2021 remained at the same level as 2020. The majority, 38 out of 68, were committed prior to July 11, 2021, when snap parliamentary elections were held in Moldova and the political power in the country shifted.

Data for the study were collected using open source content analysis in Russian, Romanian and English. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 3.

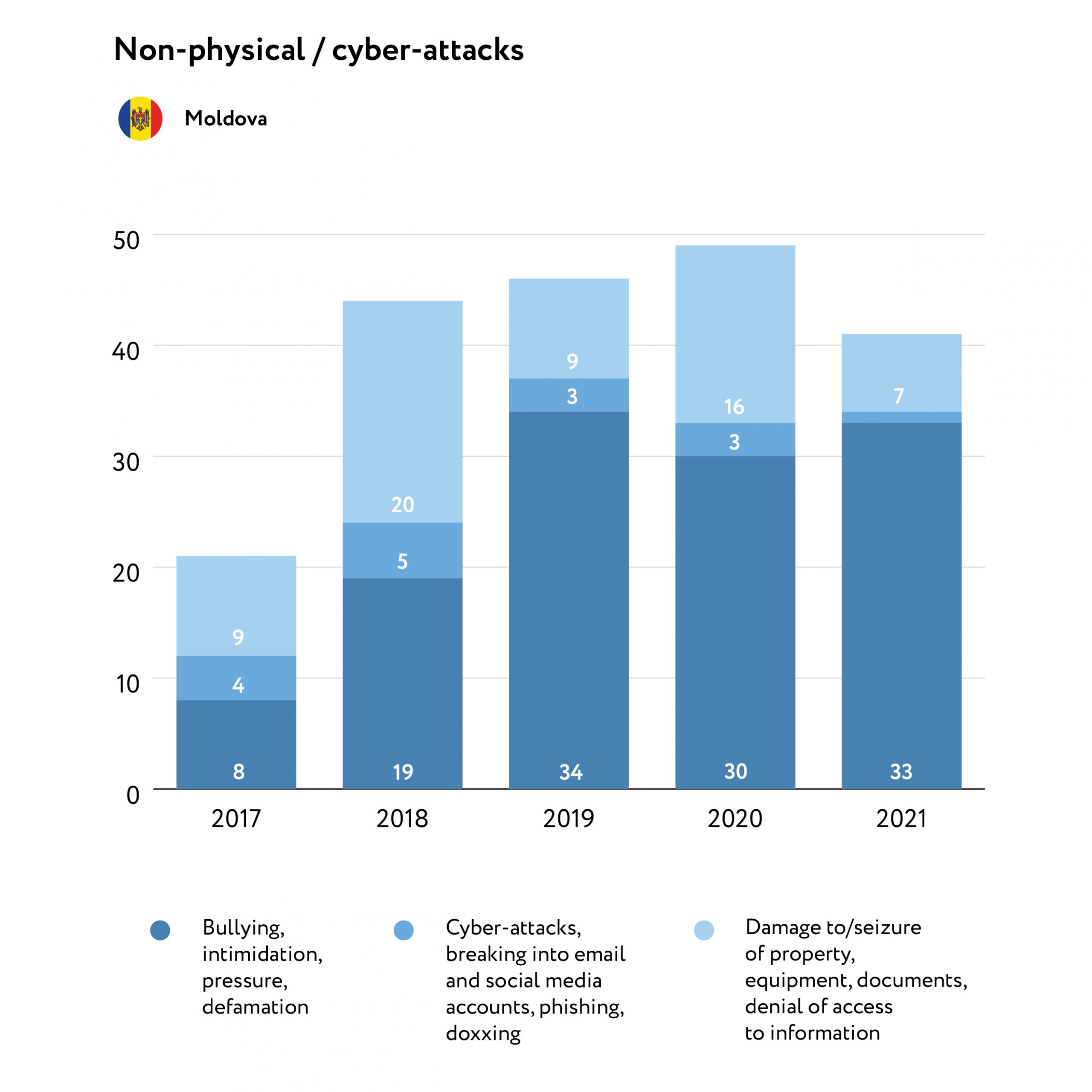

- Since 2017, attacks and threats of a non-physical nature, including cyber-attacks, remained the primary method of exerting pressure on media workers, namely through: defamation, spreading of slander and insults against journalists (21 incidents) as well as harassment, intimidation, threats of violence, including threats and defamation online (12 incidents).

- In 58 percent of cases, the main source of non-physical attacks/threats against media workers were government officials, including deputies of the national parliament and the People’s Assembly of Gagauzia, as well as other persons holding official positions at central, regional, or local levels. The majority of these attacks against journalists by government officials took place before the snap parliamentary elections, which were held on July 11, 2021.

- Four of the seven cases of physical attacks recorded in 2021 were perpetrated prior to the parliamentary elections by deputies from the Party of Socialists and employees of the State Security Service.

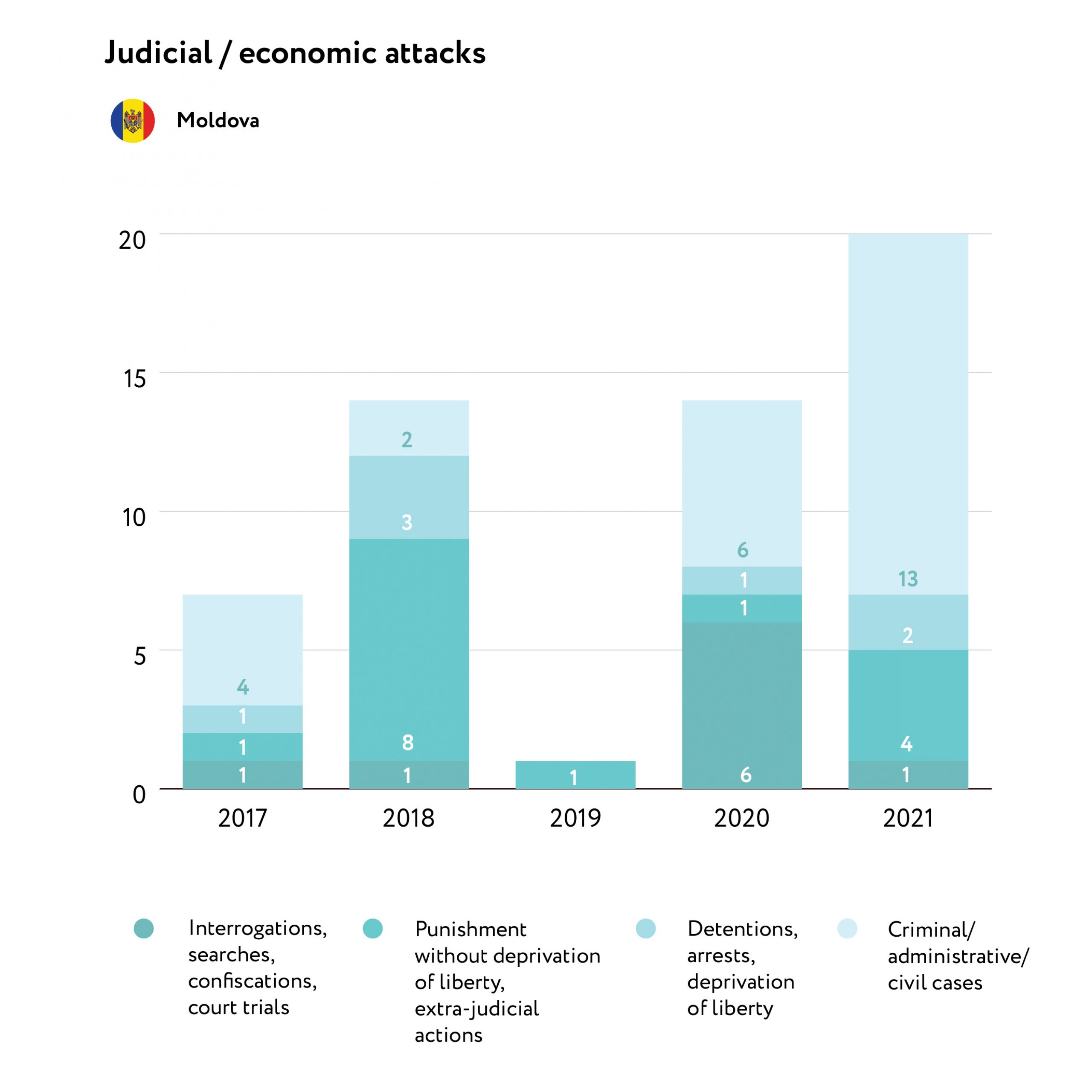

- In 2021, the number of attacks on journalists and editorial offices via legal and/or economic means increased. One of the most common methods (13 incidents) was the civil prosecution of media workers for insulting an individual’s honour, dignity, or reputation as well as violations of privacy.

- In 2021, Moldovan journalists were repeatedly subjected to harassment, smear campaigns and condemnation, usually online.

It is worth noting that some of these attacks and threats were not made public and are not reflected in media coverage, since many journalists believe that threats and online attacks are simply an inevitable part of their day-to-day professional activities, and do not report them.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN MOLDOVA

In 2021, the Republic of Moldova ranked 89th out of 180 countries in the annual press freedom index by the non-governmental organisatoin (NGO) Reporters Without Borders, a slight improvement over the previous year when it held the 91st place. In 2022, Moldova ranked 40th place.

More than 150 providers and distributors of audio-visual media operate in the country. According to data from the state regulator, the Council on Television and Radio Broadcasting, there were 64 TV channels and 60 radio stations in the country as of 2021. In 2020, according to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, 113 newspapers, comprising a total annual circulation of 19 million copies, and 195 magazines as well as other periodicals with a total annual circulation of 1.5 million copies, were published in Moldova.

According to the Public Opinion Barometer, a survey conducted by the Institute for Public Policy of Moldova in June 2021, more than 70 percent of the population use the internet on a daily basis, while around 68 percent watch television daily. About two-thirds of citizens use social media every day, about a third of the adult population reads the news or listens to the radio, while less than 10 percent read newspapers or books daily, including in an electronic format or online. Television remained the main source of information for 51 percent of respondents, while 22 percent said it was the internet. Approximately 39 percent of Moldovans trust the media completely, while 6 percent trust it “to some extent”. 18 percent of citizens trust television as a source of information, followed closely by family (16%), then social media and the internet, 13 percent each.

On July 11, 2021, as a result of snap parliamentary elections, the opposition pro-European Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS), founded in 2015 by current President Maia Sandu, became the ruling party with a parliamentary majority. This new government has introduced reforms in various areas, including in the media. The Code of Television and Radio was amended, and, on November 11, 2021, the employees of the Council on Television and Radio Broadcasting, the state regulator, were dismissed. On December 3, 2021, a new composition of the Council was introduced, taking measures to promote local television and radio programs, as well as to counter propaganda and misinformation. NGOs representing media rights called on the new administration to ensure transparency in the activities of state institutions and journalists’ access to socially-significant information. Experts also stressed the need to adopt a number of new laws, and amend existing legislation to allow for the development of independent media in Moldova.

In the latter half of 2021, the situation in the Moldovan media landscape began to change, and a regrouping in the advertising market began. Media groups controlled by representatives from former President Igor Dodon’s Party of Socialists, as well as media groups owned by businessmen and politicians Vladimir Plahotniuc and Ilan Shor, both of whom left Moldova in 2019, appeared to lose their influence.

Nevertheless, strong political affiliations of a number of media outlets in Moldova, as well as the dependence of their editorial policies on the interests of their owners, remain serious problems in the development of independent media. Equally dangerous for both the Moldovan media and the country’s security, is the fact that the information space is flooded with media from the Russian Federation, contributing to the dissemination of Kremlin narratives.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

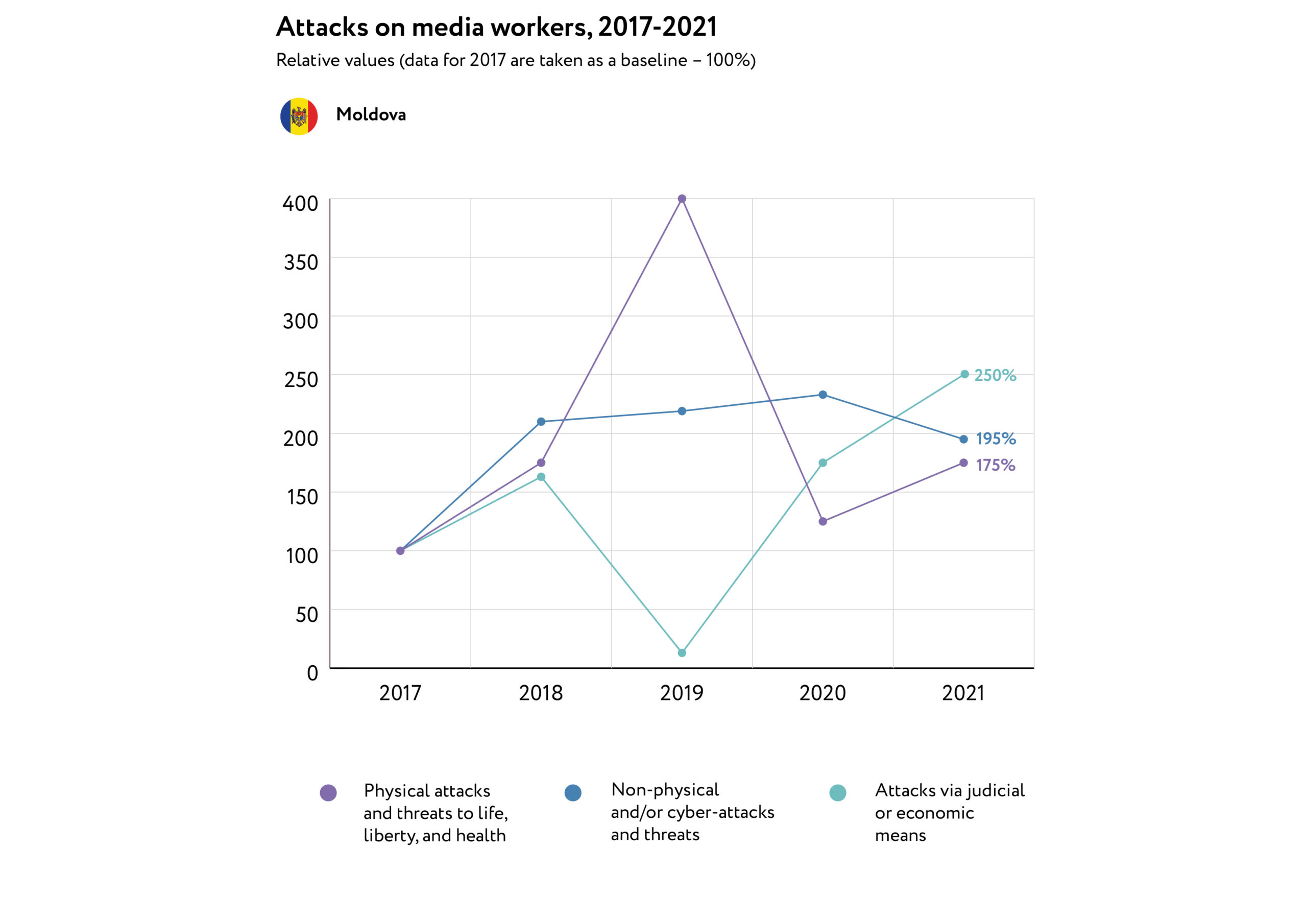

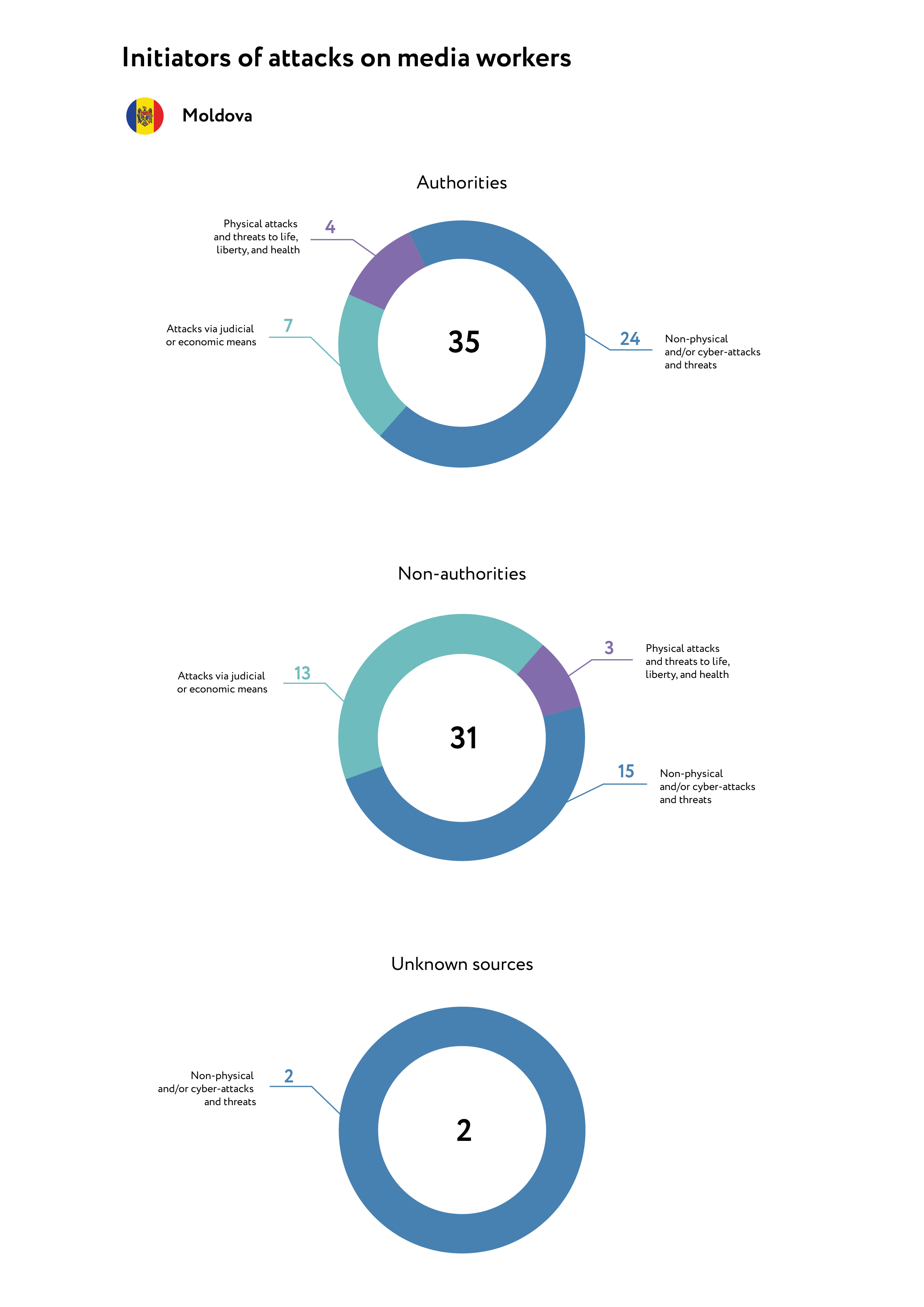

In 2021, 68 attacks were recorded – the same number as the previous year, and twice as many as in 2017. 41 (60%) of these incidents were attacks and threats of a non-physical nature, including cyber-attacks. 20 (29%) attacks were undertaken using legal and/or economic means. In seven cases (10%), media workers were subjected to physical pressure.

In 2021, in 52 percent of cases, or 35 out of 68, the perpetrators of the attacks/threats against media workers were government officials at the national and regional levels. These individuals were deputies of the national parliament and of the People’s Assembly of Gagauzia, heads of various districts and city halls, as well as other public officials. The majority of the attacks by government officials date back to the period before the July 11th parliamentary elections. Journalists have been victims of harassment, smear campaigns, attempts to discredit and slander them, intimidation, pressure and threats of violence. These acts usually took place online.

Compared to the previous year, the number of attacks on journalists by government officials decreased, down from 56 cases in 2020. In 31 cases, or 46 percent, attacks did not come from government officials, but from private individuals or companies, mostly consisting of lawsuits following the publication of investigative journalism.

In 2021, employees or editorial offices of 21 media institutions, media projects and YouTube news channels were subjected to attacks/threats. Most of these attacks were perpetrated against TV8 and Jurnal TV, 13 and 11 respectively, the Ziarul de Gardă newspaper(5), the CU SENS media project and the regional portal Nokta.md from the city of Comrat (7 each). RISE Moldova employees were also targeted in 2021, as were the Centre for Investigative Journalism and Anticoruptie.md. In addition, several regional outlets were targetted: Nordnews.md and Esp.md, both based in the city of Bălți, Tuk.md in Taraclia and the TV channel PRO TV Chisinau.

4/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

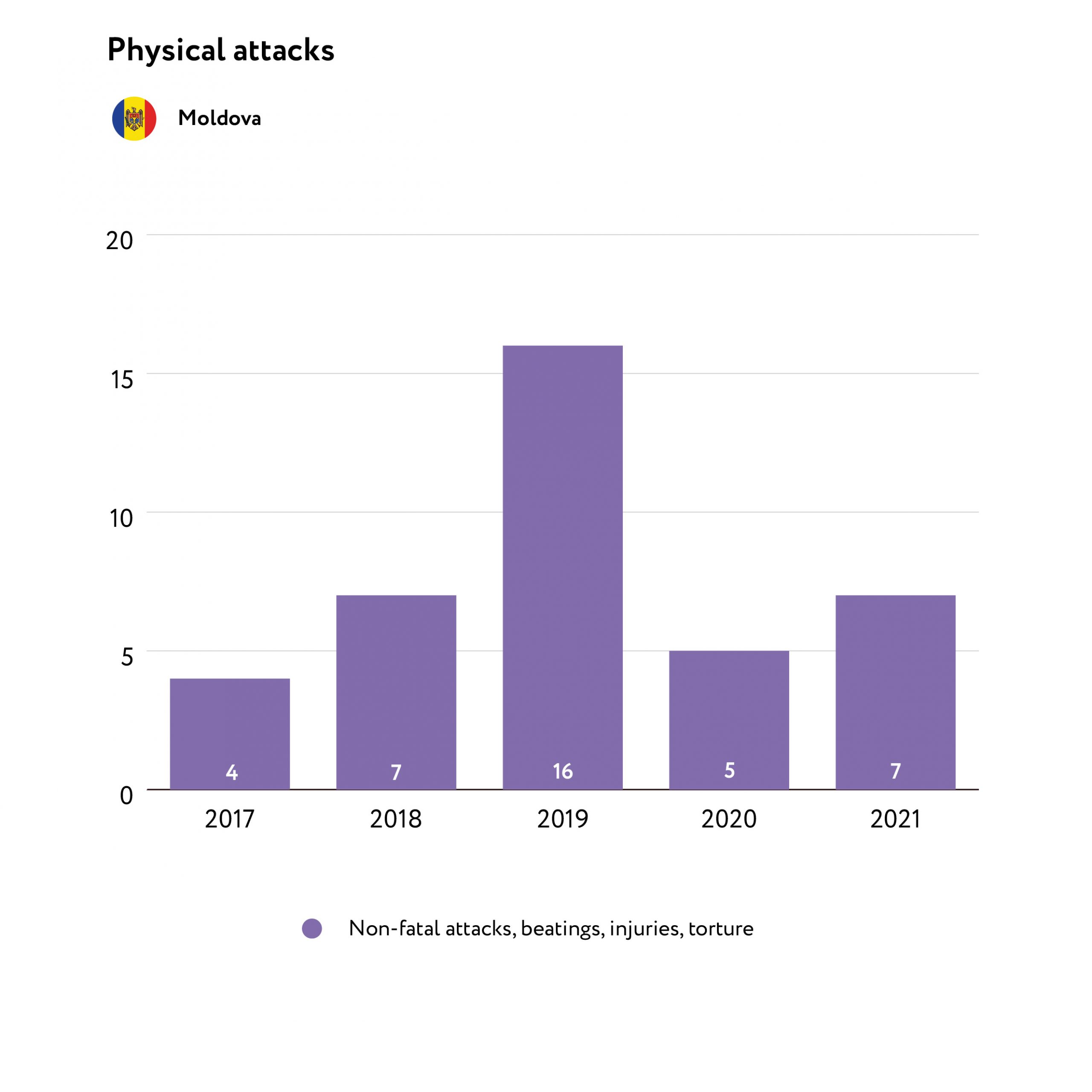

In 2021, seven cases of physical attacks and threats to the life and health of media workers were recorded. For comparison, in 2020 there were five cases and in 2019 there were 16. In four of the 2021 cases, the attacks were perpetrated by government officials prior to the parliamentary elections.

Some examples of attacks in 2021 Include:

- On January 19, an employee of the State Security Service, assigned to former President Igor Dodon, prevented a PRO TV Chisinau journalist, Andreea Iriciuc, from asking Dodon questions and pushed her away.

- On May 25, a group of journalists from Nordnews.md and Deschide.md, who filmed a meeting of Socialist deputies on private property, were attacked and threatened by one of these parliamentarians, Mihail Paciu.

- On June 3, Viktor Moshnyaha, a journalist from the newspaper Ziarul de Gardă, was hit by a car while filming an investigation about timber theft.

- On July 7, Nikolay Kosher, a journalist from Nordnews.md, was prevented from attending a meeting between Igor Dodon and voters in Bălți. Party of Socialists deputy, Alexander Nesterovsky, along with his associates, grabbed the journalist to prevent him from entering the hall where the meeting was taking place.

- On December 2, a film crew from Jurnal TV was attacked by businessman Nikolae Pelin. Having refused to answer the journalists’ questions, Pelin attacked them with a rock in an attempt to damage the camera before threatening to smash up the crew’s car.

5/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

Attacks and threats of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks, remain the most common form of pressure on journalists in Moldova. In 2021, 60 percent of attacks and threats were non-physical in nature. This figure is slightly lower than in 2020.

The main methods of non-physical attacks are: defamation, slander against media outlets or an individual journalist (21) and harassment, intimidation or pressure as well as threats of both violence and death. This includes 12 incidents of online attacks.

Cases of defamation and spreading slander against journalists and editorial offices have decreased in comparison to last year, while cases of harassment, intimidation and threats of violence, including online attacks, have become three times more common, up from four to 12. There were five cases of illegal obstruction of journalistic activity and denying access to information, three times fewer than in 2020. In 24 out of 41 cases of non-physical attacks, the perpetrators were government officials at the national and regional levels.

Examples of attacks and threats of a non-physical nature and/or cyber-attacks that took place in 2021 include:

- On February 2, investigative journalist Cornelia Cozonac was harassed on social media, and in some news outlets, for speaking out about the history and status of the Russian language in Moldova.

- On March 12, journalists from Nokta.md were prevented from attending a meeting of the Comrat municipal council. The chairman of the council, Georgy Zlatov, insisted that the cameraman stop filming the meeting with disgruntled market merchants. Zlatov approached the journalist and threw his phone on the ground.

- On March 25, the chairman of the Rîșcani district, Vasile Secrieru, accused seven regional and national media outlets of spreading fake news and demanded they retract it. Nordnews.md, Protv.md, Newsmaker.md, Tv8.md, Stiri.md, Jurnal.md and Ziarulnațional.md wrote that he purchased and renovated an apartment for himself using state money.

- On May 5, on TV8’s Cutia Neagra, politician Renato Usatii rudely accused the presenter of spreading propaganda and “serving” certain politicians.

- On June 8, journalist Alina Radu, director of the weekly investigative paper Ziarul de Gardă, was harassed on social media by politically affiliated media outlets. The mayor of Taraclia, Vyacheslav Lupov, has repeatedly insulted journalists from Tuk.md – calling them “shameless liars”, “provocateurs”, “gang members” and a “criminal group”.

- On July 9, Aleksandr Odnostalko, an MP from the ruling Party of Socialists, called Jurnal TV a “fascist TV channel”.

- On August 11, the Centre for Investigative Journalism’s website, Anticoruptie.md, was subjected to several cyberattacks. As a result, access to the site was blocked.

- In September, following a statement from journalist Natalia Morari about her personal relationship with businessman Vyacheslav Platon, who was involved in financial fraud, and whom she repeatedly invited to her programs on TV 8, insults and slanderous statements were circulated online on websites and social networks against journalists from the channel, as well as employees of other Moldovan independent media outlets. Morari, along with Vasile Botnaru,director of Radio Free Europe Moldova, Val Butnaru, the director of Jurnal TV, and TV 8 journalist Marianna Rata were accused by local politicians of having connections to to either or both the Russian FSB and the Special Services of Moldova.

- On November 18, Bălți mayoral candidate Nicolai Chirilciuc, of the Patriots of Moldova party, threatened and insulted Slava Perunov, the publisher and director of independent publication Esp.md. Perunov informed both the police and electoral authorities about these threats.

6/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

In 2021, 20 cases of attacks via legal and/or economic means were recorded, making up 29 percent of the total number of attacks and threats. The number of such attacks increased by around 50 percent compared to the previous year.

Attacks via legal and/or economic means were perpetrated against eight newsrooms and their employees, including: CU SENS (7 cases), RISE Moldova (3 cases), TV8(3 cases), Jurnal TV, and Ziarul de Gardă newspaper, as well as the online news websites Newsmaker.md and Nokia.md.

In 2021, 13 civil lawsuits were filed for defamation, insults to honour, dignity and reputation and/or violations of privacy. These were filed against the CU SENS (6 lawsuits), RISE Moldova (2 lawsuits), Jurnal TV, Ziarul de Gardă, as well as Newsmaker.md and Nokia.md.

Examples of legal actions include:

- On April 12, after RISE Moldova reported MP Ilan Shor was hiding in Israel, having been accused of fraud and corruption in Moldova, Shor sued the journalists, accusing them of lying, manipulating data and “public lynching”.

- On August 3, after a Ziarul de Gardă investigation into illegal logging and deforestation was published highlighting the interests of the chairman of the Hîncești court, Mihail Macari and his son, lawyer Alexandru Macari, the latter filed a lawsuit against the newspaper for insults to his honour, dignity and reputation.

- On December 10, after the publication of an investigation into government spending on distance learning, Accent Electronic, which supplied laptops to schools, filed a lawsuit against CU SENS for spreading false information and damaging their business reputation. The CU SENS project was subject to a second civil lawsuit from the owner of the company, Vladimir Russu.

In 2021, two online resources were blocked:

- On September 14, following anonymous complaints, Știrile TV8, one of TV8’s YouTube channels, which broadcasts live news and publishes news reports, was blocked.

- On September 16, following anonymous complaints, the independent YouTube channel Lisa News was blocked.

Two journalists were detained:

- On February 9, peacekeeping forces detained TV8 journalists Viorica Tataru and Andrei Captarenko by on a bridge in the village of Gura Bîcului, near the administrative border with Transnistria. The soldiers demanded that the journalists delete their footage, threatening to confiscate the equipment if they did not comply. The journalists refused. After two hours of detention and negotiations, the journalists were released.

ANNEX 1: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (ARMENIA)

- Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression – a civic organisation operating in Armenia, engaged in studying the situation in the realm of freedom of speech and publishing periodic reports, as well as defending the rights of journalists and media outlets.

- Yerevan Press Club – an NGO, the principal goal of which is support and development of free, independent, and quality media.

- Media Initiatives Center – an Armenian NGO, the main mission of which is to create and disseminate free and independent content and by means of this to promote the all-encompassing and harmonious development of society.

- Hetq.am– the internet publication of the Armenian civic organisation Investigative Journalists.

- Freedom House – an international human rights NGO that evaluates and publishes reports on the level of freedom in 210 countries and territories worldwide, including on freedom of speech and media activity.

- Reporters Without Borders – an international NGO whose aim is to protect journalists who are being subjected to persecution for doing their job.

- The Committee to Protect Journalists – an international organisation engaged in defending the rights of journalists.

- DataLex.am – the database of Armenia’s judicial system.

- Region research centre – an Armenian civic organisation that studies the regional problems of the South Caucasus, including those concerning media activity.

- Haykakan zhamanak [Armenian Times] – a daily newspaper.

- Factor.am – an Armenian multimedia news portal.

- Radio Azatutyun – the Armenian service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

ANNEX 2: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (GEORGIA)

- Gruziya Online – a news agency about events in Georgia, in the Russian language.

- On.ge – a news website about events in Georgia and the Caucasus, in the Georgian language.

- Media.ge – a news and analysis website, a project of the Internews-Georgia organisation — a media portal in the Georgian, Russian, and English languages.

- Civil.ge – a news and analysis website, a project of the UNO Association of Georgia, in the Georgian, Russian, and English languages.

- Caucasian Knot – a news and analysis website about events in the Caucasus, in the Russian language.

- Sova – an online magazine about the politics, economy, and life of Georgian society in the Russian language.

- Radio Tavisupleba – the website of Radio Liberty’s Georgian service, in the Georgian language.

- Formula TV – a news television channel, in the Georgian language.

- Detals.net – a news portal about events in Georgia and the surrounding region, in the Russian language.

- IPN – a news website about events in Georgia, in the Georgian, English, and Russian languages.

- Tabula – a news and analysis website about the politics and economy of Georgia, in the Georgian language.

- Novosti Gruziya – a news website about events in Georgia, in the Russian language.

- Newsreport.ge – a news website about events in Georgia, in the Georgian language.

- Batumelebi – a newspaper and website with news about events in the Autonomous Republic of Adjara and Georgia, in the Georgian language.

- Mtavari Arkhi – a television channel, in the Georgian language.

- First Channel – the news website of the Public Broadcasting of Georgia television channel, in the Georgian and Russian languages.

- Netgazeti.ge – a news and analysis website about events in Georgia, in the Georgian language.

- Adjara TV – the news website of Public Television Broadcasting of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, in the Georgian language.

- Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics – the website of an NGO engaged in problems of ethics in the work of the media and journalists, in the Georgian and English languages.

- Radio Pirveli – the website of the radio station of the same name, in the Georgian language.

- Caucasian Echo – the website of a project of Radio Liberty’s Georgian Service, in the Russian language.

- GHN – a news and analysis website about events in Georgia and the world, in the Georgian, English, and Russian languages.

ANNEX 3: OPEN SOURCES USED FOR GATHERING DATA (MOLDOVA)

- Reporters without Borders — an international non-profit and non-governmental organization with the stated aim of safeguarding the right to freedom of information.

- Broadcasting Coordinating Council of the Republic of Moldova

- National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova

- Institute for Public Policy of Moldova

- Association of Independent Press (API)

- Independent Journalism Centre (CJI)

- Nordnews.md – a regional internet news portal in the Romanian language (city of Bălți).

- Ziarul de Gardă – a daily newspaper in the Romanian and Russian languages in electronic and print formats.

- NewsMaker.md – an internet news portal in the Russian and Romanian languages.

- PRO TV Chișinău – a branch of the Romanian television channel in Moldova.

- Agora.md – an internet news portal in the Romanian language.

- TV8 – a television channel.

- Nokta.md – a regional internet news portal in the Romanian language (city of Comrat).

- Jurnal.md – an internet news portal in the Romanian language.

- Ziarulnational.md – an internet news portal in the Romanian language.

- Stopfals.md – a fact-checking internet portal in the Romanian and Russian languages.

- Rise.md – the internet portal of a group of investigative journalists.

- Social networks, including Facebook and Telegram channels.

ANNEX 4: ATTACK TYPES, IDENTIFIED BY THE JUSTICE FOR JOURNALISTS FOUNDATION

Physical attacks and threats to life, liberty, and health

- Abduction, taking captivity/hostage, illegal deprivation of liberty

- Attempted murder

- Beating / injury / torture resulting in death

- Death while in custody or as a result of loss of health in captivity

- Disappearance

- Fatal accident

- Murder

- Non-fatal accident

- Non-fatal attack / beating / injury / torture

- Pressure on a media worker via physical pressure on relatives and loved ones

- Punitive psychiatric treatment not resulting in death

- Punitive psychiatric treatment resulting in death

- Sexual harassment

- Sexual violence

- Sudden unexplained death

- Suicide

- Suicide attempt

- Unlawful military conscription

Non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats

- Breaking into email / social media accounts / computer / smartphone

- Bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber-

- Cyber-, DDOS, and hacker attack on a media outlet

- Damage to / seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials, print run

- Damage to/seizure of the residence/work premises

- Defamation, spreading libel about a media worker or media outlet

- Forced emigration as a result of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats

- Identity theft / phishing / doxxing

- Illegal impediments to journalistic activity, denial of access to information

- Pressure on a media worker via non-physical pressure on relatives and loved ones

- Pressure on a source, including threats of violence and death

- Trolling

- Wiretapping/surveillance without a court decree

Attacks via judicial or economic means

- Administrative arrest, remand, pre-trial detention, prison

- Arrest in absentia

- Arrest of bank account/ property

- Authorised travel ban (movement inside a country or specific region/town)

- Ban on engaging in journalistic activity

- Ban on entering the country, denial or revocation of a visa/accreditation

- Ban on leaving the country

- Community service, ban on certain activities and other punishment following a criminal case

- Confiscation/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials

- Court trial

- Criminal/administrative prosecution excluding (1), (2) and (3)

- Dismissal / involuntary dismissal /forced quitting of the profession

- Fine for non-compliance with the «foreign agents» law in accordance with the Criminal Code

- Fine for non-compliance with the «foreign agents» law in accordance with the Code of Administrative Offences

- Fines and other restrictions following administrative offences

- Forced cessation of journalistic activity/ closure of media outlet due to the state of war and/or military censorship

- Forced deportation, Extradition

- Forced emigration as a result of legal/economic pressure

- House arrest

- Interrogation

- Labelling media/individuals as foreign agents

- Pressure on a media worker via judicial and/or economic means on relatives and loved ones

- Prosecution for dissemination of false information and fakes (3)

- Prosecution for extremism, links with terrorists, inciting hatred, high treason, calling for the overthrow of the constitutional order, rehabilitation of Nazism (2)

- Prosecution for libel, insult, violation of privacy (1)

- Prosecution for violation of the honour, dignity and business reputation; violation of privacy following civil lawsuit

- Repayment of compensation and legal costs following civil lawsuits

- Request to remove or block the article and/or refutation

- Search with a court decree

- Search without a court decree

- Selective application of repressive laws

- Short-term detention

- Shutting down a media outlet / blocking an Internet site/ seizure of an entire print run

- Suspended sentence

- Unauthorised travel ban (inside country, region or town)

- Warnings, pre-trial complaints, questioning and other extra-judicial actions

- Wiretapping/ surveillance with a court decree