BELARUS

AN INDEPENDENT EXPERT OPINION ABOUT ATTACKS ON MEDIA WORKERS IN BELARUS REPORT

The Justice for Journalists Foundation’s report seems to me to be a document that is rather precise, clear, concrete, and comprehensive from the point of view of the facts. In the report, the principal cases of violation of freedom of speech and of the rights of journalists in the course of 2020 — the beginning of the year 2021 are recorded, while the violators of these rights and the main trends in the suppression of freedom of expression in the country are clearly indicated.

It is worth adding that the largest independent internet portal in Belarus, Charter97.org, is being subjected to illegal blocking since 2018. In 2020 the blocking of the website intensified: in particular, “mirror” sites were blocked; likewise, mass DDoS attacks were used against our media, and Charter97.org’s documentary films were being blocked on YouTube at the demand of Belarusian structures of power.

Besides that, it is important to mention the criminal cases in relation to Belarusian bloggers Sjarhej Pjatrukhin, Dzmitryj Kazloŭ, Aljaksandr Kabanav, Ŭladzimer Cyhanovič, Ihar Losik, Paval Spiryn, and others. They are being held in detention for over half a year already on made-up charges, and face the spectre of a prison term.

I hope that the given report on violation of freedom of speech in Belarus will be taken notice of by international structures: both human-rights ones and those responsible for the foreign policy of the states of the EU and the USA, because the violations enumerated in the report are compelling grounds for introducing serious sanctions against Belarus’s dictatorial regime.

Natallia Radzina, editor-in-chief, Charter-97 website (Belarus)

Author of the report – Belarusian Association of Journalists

1/ KEY FINDINGS

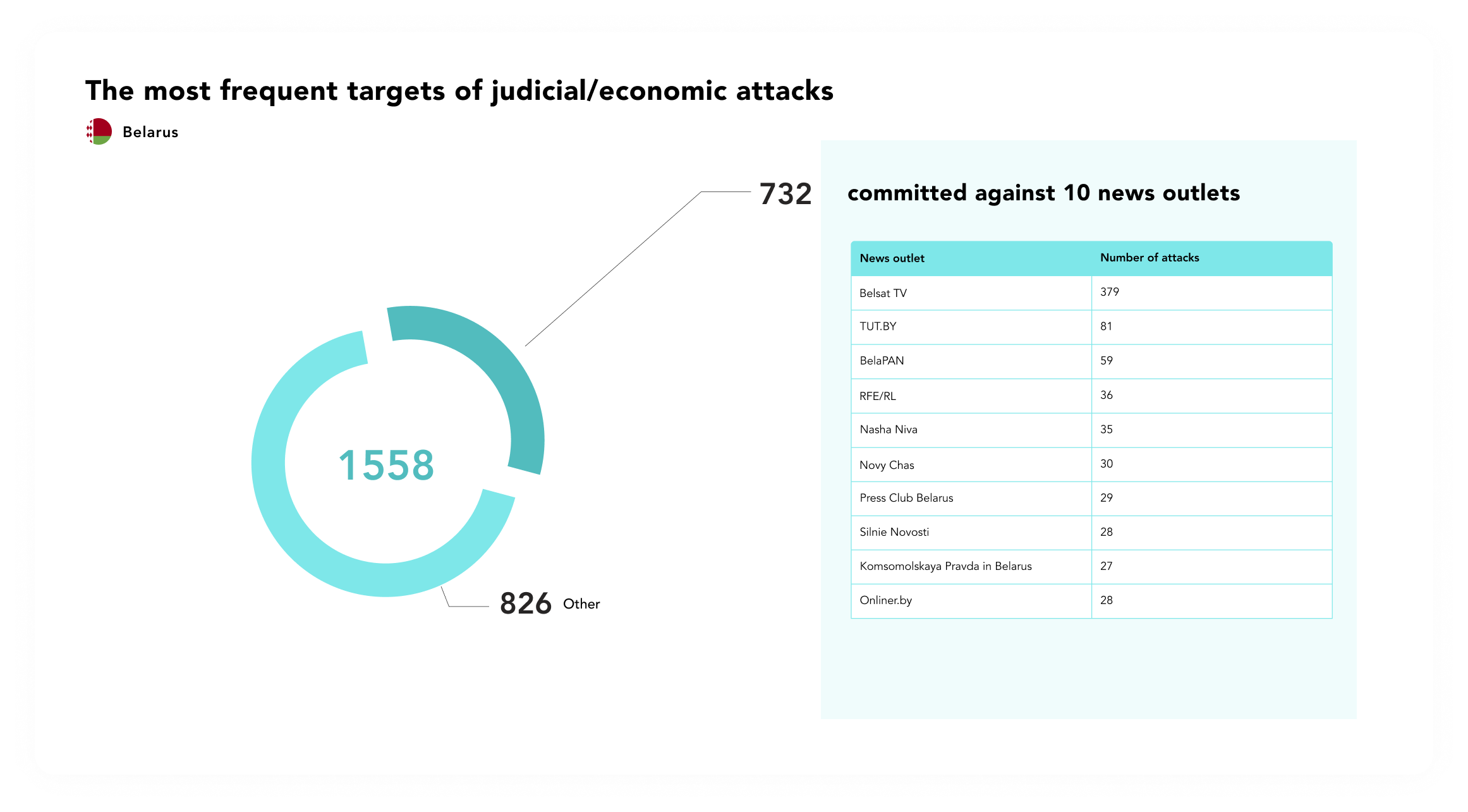

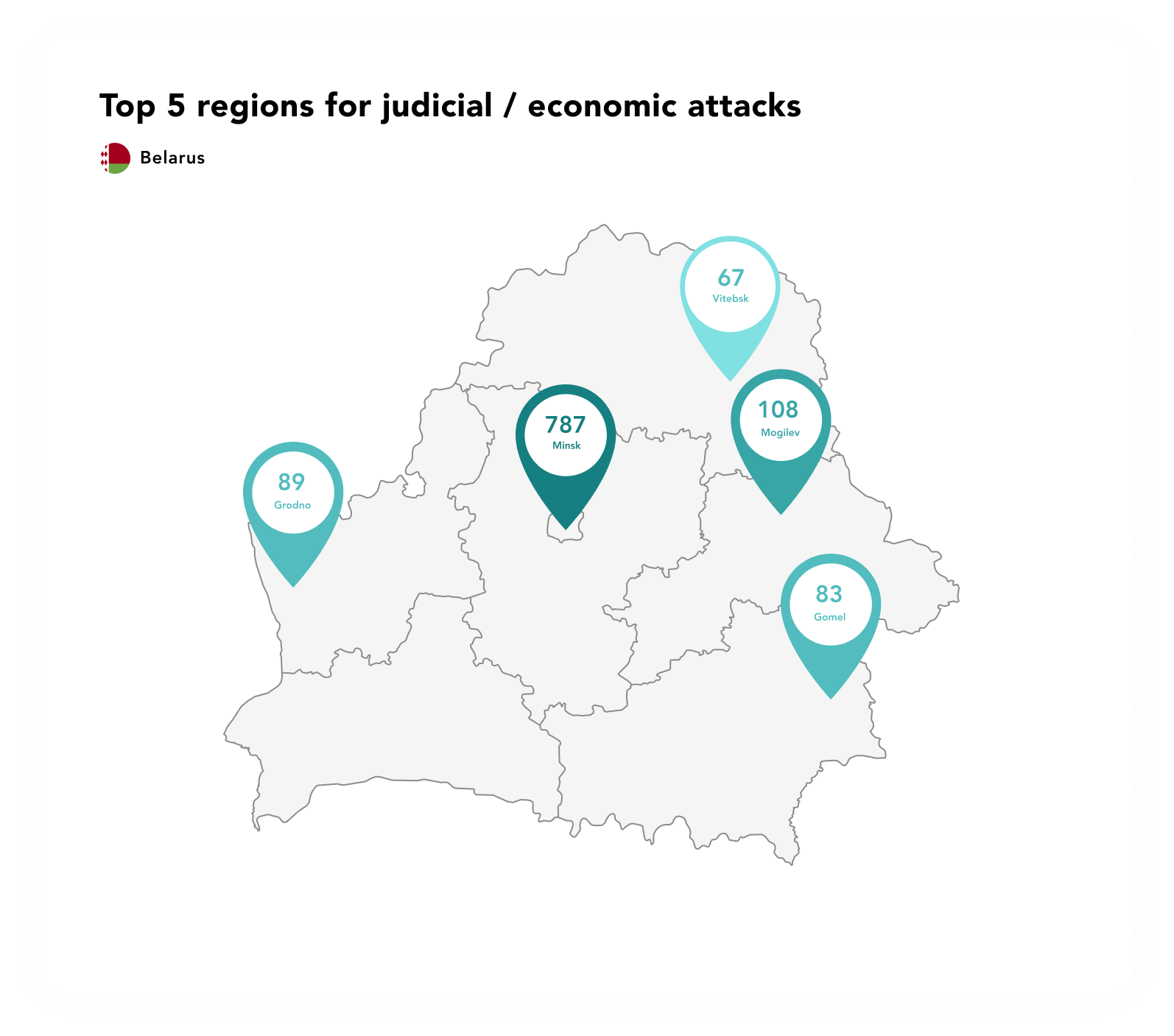

1558 instances of attacks/threats in relation to professional and citizen media workers and editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Belarus in 2020 were identified and analysed in the course of the research. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Belarusian, and English languages using the method of content analysis. A list of the main sources is presented in the Annex 5.

- The quantity of attacks on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in 2020 exceeded the sum total of attacks throughout 2017-2019 (1079) by 1.4 times.

- Attacks via judicial and/or economic means were the most widespread form of pressure on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in Belarus. 1385 incidents were recorded in the given category.

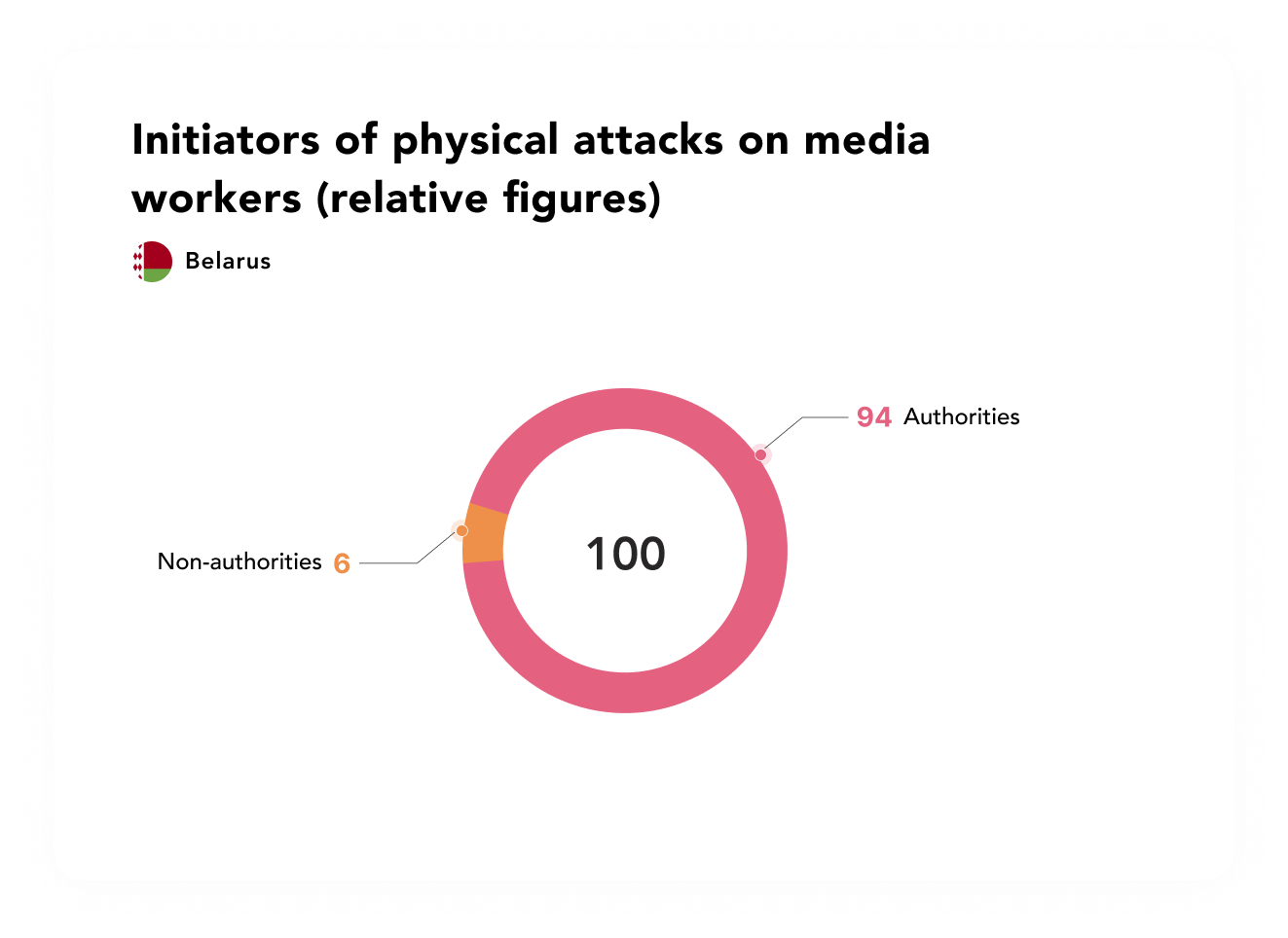

- The majority of physical attacks could be attributed to attacks on the part of representatives of the authorities (91 out of 96 incidents). During a protest against the falsification of the results of the presidential elections, riot police were deliberately targeting journalists for beating and humiliation.

- More than 30 journalists were deported from Belarus and banned from entering the country for a period ranging from 5 to 10 years, including at least 19 journalists from foreign media outlets.

- In 96% of the instances, the attacks against journalists were coming from representatives of the authorities (1506 out of 1558 incidents).

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN BELARUS

Belarus holds 153rd place out of 180 in the Reporters Without Borders annual freedom of the press index for 2020, falling between Brunei and Turkey.

In the Freedom on the Net rating of the international human rights organisation Freedom House, Belarus’s level of freedom on the net put it into the category of countries with an unfree internet in 2020, with 38 points out of 100.

Two events had the biggest impact on the situation in the media sphere in Belarus in 2020. First, this was the authorities’ attempts to restrict the dissemination of information about COVID-19 in the country. And second, the political and legal crisis after the elections of the president that took place on 9 August 2020.

The mass protests, which began in the country after the Central Electoral Commission announced the official results, were cruelly suppressed by riot police. The demonstrators were demanding the conducting of new elections, the release of political prisoners, a stop to violence, and punishment for the persons guilty of using it. The authorities were responding with harsh measures, administrative detentions, and the opening of criminal cases.

According to the assessment of the Vesna human rights centre, 33 thousand people were detained in the country during the time of the elections and in the post-election period; many of these were subsequently arrested or fined in administrative order. Vesna documented about 1000 witness accounts of torture; no fewer than four people perished. By the end of 2020, 650 people had become subjects in criminal cases connected with the elections and the mass protests; Vesna recognised 169 of them as political prisoners. However, not a single criminal case was opened due to the acts of violence on the part of the riot police and the death of protesters.

Pressure on media workers, journalists, and bloggers intensified sharply in 2020. The vast majority of the attacks on them fell in the post-election period. The situation in which journalists had to work sharply deteriorated.

STATE MEDIA OUTLETS

According to the data of the Ministry of Information, as of 1 January 2021 there were 1626 print media outlets registered in Belarus (there were 1614 a year earlier). Of these, 438 print media outlets are state-owned. The state media outlets receive preferential advantages and funding from the state budget allocated on a non-competitive basis. In 2020 the funding exceeded 73 million US dollars; the main part of this sum was directed towards funding Belgosteleradiokompaniya [the state broadcaster] (more than 55 million US dollars).

Of the 261 registered television and radio programmes, the overwhelming majority (188) are state-owned. The remaining television and radio channels are under the total control of the authorities, be they local or national, thanks to the system of registration and licensing.

As a sign of protest against violence and the need to justify it on the air, after the elections dozens of employees of the state media outlets resigned or were dismissed after participating in protests. Some of them were arrested, and likewise one criminal case was initiated.

INDEPENDENT MEDIA OUTLETS

The vast majority of non-state print media outlets are strictly entertainment and advertisement. According to the data of the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ), there are no more than 30 registered non-state media outlets of a socio-political nature. Six of them ran into problems with distribution and printing in the second half of 2020 and were forced to cease coming out in printed format.

FOREIGN MEDIA OUTLERS

The state monopoly on broadcasting is undermined by foreign stations. A particular role is played by Radio Svoboda [Radio Liberty], European Radio for Belarus, Radio Ratsyia, and the Belsat satellite channel (the last three of which are registered in Poland). Their broadcasts are oriented towards Belarusians and are prepared predominantly by Belarusians.

However, neither Belsat nor Radio Ratsyia have lawful status in Belarus, despite attempts to open correspondent offices and obtain accreditation for their journalists. Freelancers who work with them are subjected to pressure on the part of the authorities; they are fined for “violating the order for the production and dissemination of mass information media output” (art. 22.9 of the Code on Administrative Violations).

Previously, Radio Svoboda and European Radio for Belarus journalists had received MFA accreditation every year; however, after the elections, under the pretext of elaborating a new statute on accreditation, the MFA revoked the accreditation of all foreign correspondents, including the employees of these media outlets. Radio Svoboda and European Radio for Belarus had still not been able to get new accreditation for their correspondents as of the end of the year.

INTERNET AND SOCIAL MEDIA

The freest sector of Belarus’s information space remains the internet. In all, there are seven non-state and 26 state net publications registered in Belarus as of 1 January 2021. Over the course of the year, only two non-state internet sites obtained registration as a media outlet. This is associated with the complexity of the registration requirements, while the advantages of having such registration are not self-evident in light of the existing conditions.

After eight months of unsuccessful attempts to register as a net publication, the Media-Polesye internet site received this status concurrently with a warning from Mininform, which is in fact how the editorial office found out about the registration in the first place. Subsequently, this allowed the police to fine Media-Polesye a hefty sum for violating the legislation on mass information media.

Pursuant to a lawsuit by the Ministry of Information, the largest Belarusian internet portal, TUT.by, had its status as a media outlet revoked.

All internet sites with an independent editorial policy were blocked on election day. Access to many of them is restricted in the country to this day. What is more, for three days the internet in Belarus was factually shut down. Later, shutdowns of mobile internet in Minsk took place regularly on the days of protests.

In these conditions, Telegram has acquired widespread popularity. However, the owners and administrators of many popular Telegram channels have been subjected to criminal prosecution. One of the vivid examples – pressure on the NEXTA Telegram channel, which was recognised as extremist.

Representatives of the authorities are declaring that the journalists of internet sites not registered as net publications do not enjoy the status of journalists and are not implementing professional activity as journalists.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

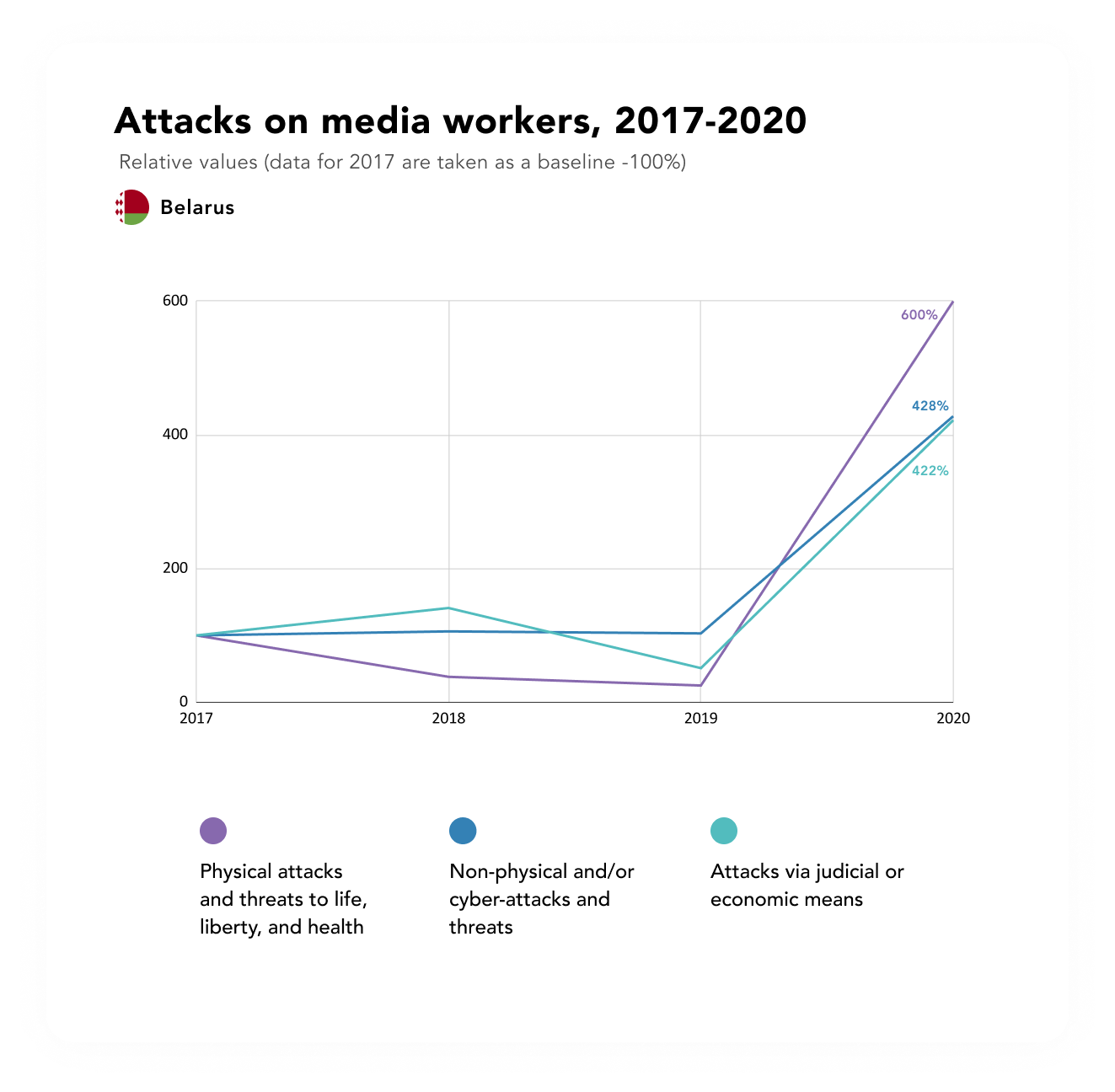

The graph below represents the general analysis of attacks of the three main categories of attacks/threats on media workers in Belarus.

2020 turned out to be the most difficult one for Belarusian media and journalists in all the period that the situation with the media in Belarus has been monitored. The number of attacks against journalists, bloggers, and media outlets significantly exceeded the numbers for the three previous years combined. 1558 attacks on media workers were recorded in 2020; 88% of these (1385) fell into the category of attacks via judicial and/or economic means.

In addition to this, 2020 saw the largest number of physical attacks and threats in relation to journalists and bloggers – 96, which is four times more than over the three previous years in aggregate.

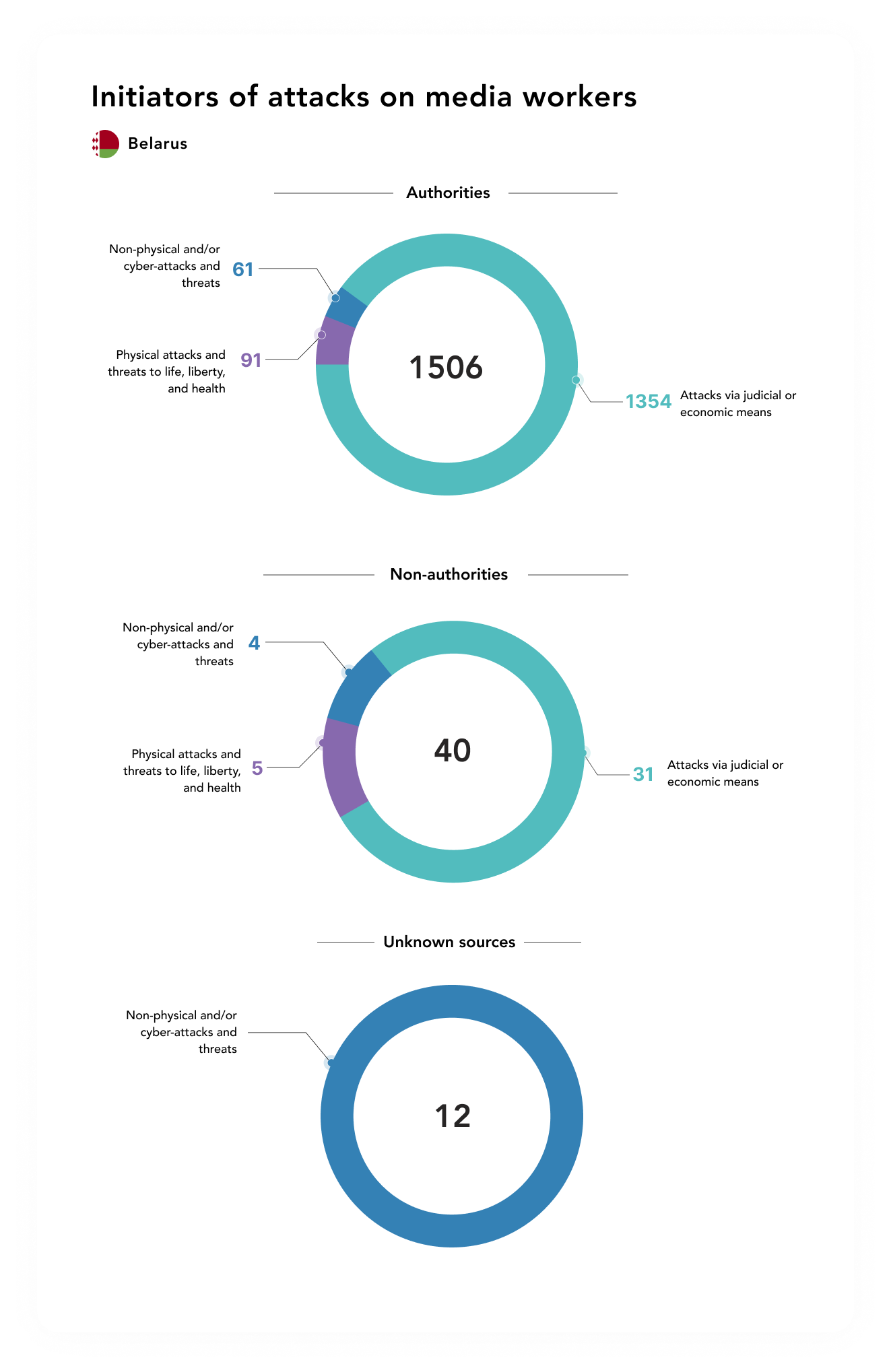

In 96% of the instances, the attacks in relation to journalists came from representatives of the authorities (1506 incidents out of 1558). 40 attacks were from non-representatives of the authorities and 12 from unknown perpetrators.

In 2020, the actions of the authorities with respect to restricting freedom of expression of opinion acquired a systemic nature and a hitherto unseen scope. Pressure was being exerted in all spheres associated with the media, with the use of the following repressive measures:

- detentions and arrests of journalists, oftentimes with the use of violence, damage to and impounding of professional equipment, and removal of material that had already been shot;

- initiation of criminal cases against journalists and media specialists;

- blocking of the internet in the first days after the elections and constant restrictions on mobile internet during mass protests;

- restriction of access to internet sites independently covering the political situation, obstacles to the printing and distribution of several non-state newspapers;

- revocation of the status of a media outlet for the largest internet portal in Belarus, TUT.by;

- recognition of NEXTA‘s popular Telegram channel and logo as extremist materials;

- denials of accreditation to foreign correspondents who had come for the elections and subsequent revocation of accreditation for all correspondents of foreign media outlets;

- dismissals,harassment and persecution of state media outlet journalists who had spoken out against the dissemination of unreliable propagandistic information.

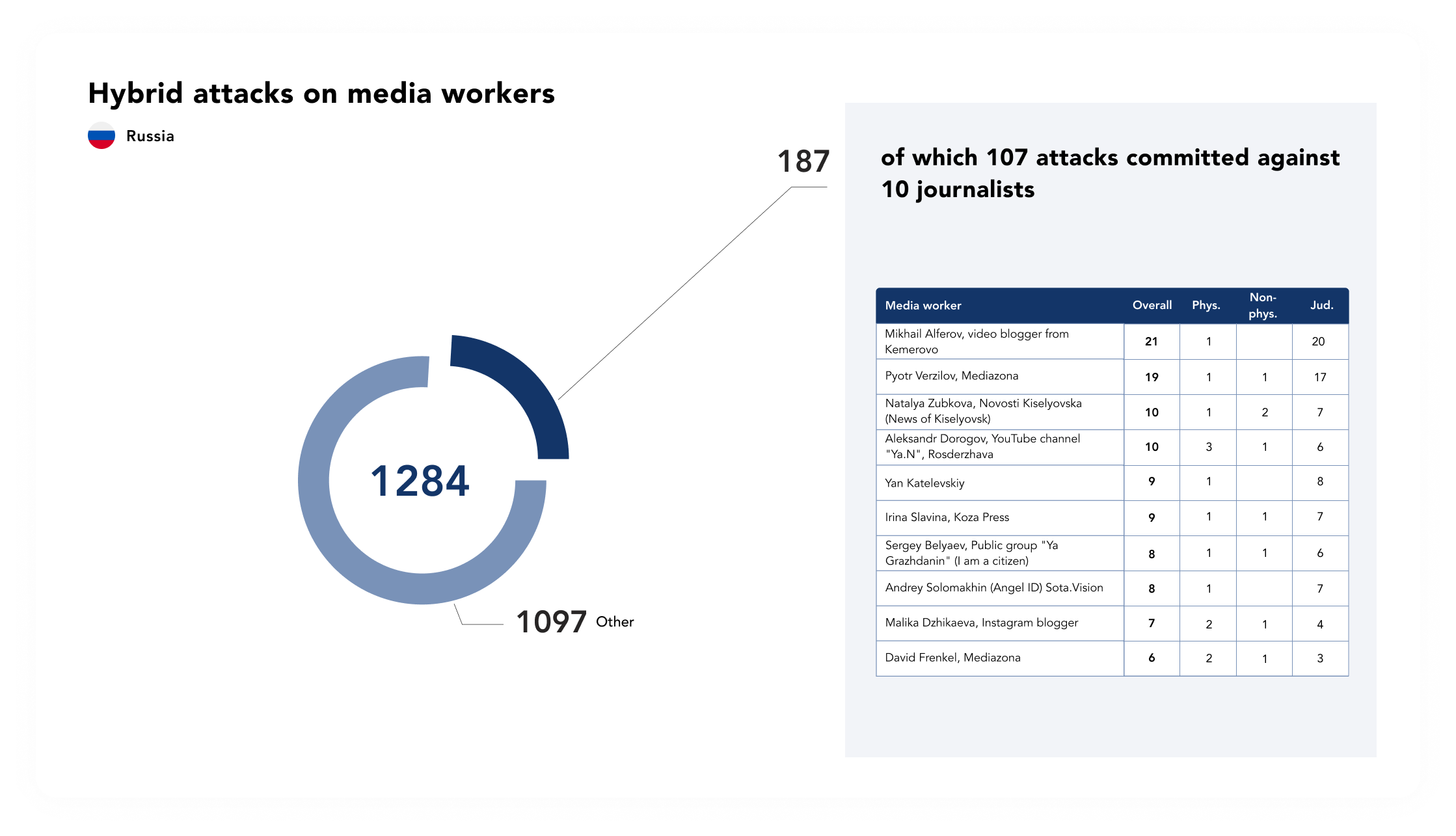

For the purposes of more precisely reflecting combination assaults on media workers in 2020 we are introducing a new category of attacks – hybrid.

We are calling systematic persecution of some publication or media worker with the use of tools from two or more categories of assaults – physical, non-physical, and judicial/economic – “hybrid”. Such a combination of means involving and not involving force with judicial means of pressure on undesirable journalists is carried out with a view to demoralising them or getting them to self-censor or to give up the profession or even life itself.

In 2020, 162 hybrid attacks were recorded. Presented below is the list of the journalists and bloggers who were being subjected to the most intensive hybrid attacks in 2020.

4/ PRESSURE ON MEDIA WORKERS UNDER THE PRETEXT OF RESTRICTIONS CONNECTED WITH THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Belarus turned out to be one of the few European countries in which quarantine was not declared in connection with COVID-19. Furthermore, for a long time the authorities were denying the seriousness of the illness. President Alexander Lukashenko [“Lukashenka” in Belarusian] was calling the pandemic a “psychosis” and an “infodemic” and called upon the Ministry of Information and the state security services to fight the disseminators of “hype” on the subject of COVID-19.

On 21 March, Lukashenko publicly addressed the chairman of the State Security Committee with a call to “deal with the lowlifes who are putting out these hoaxes” [about deaths from COVID-19 – Ed.]: “Enough of looking at this. We need to go through these sites and channels nice and thorough”.

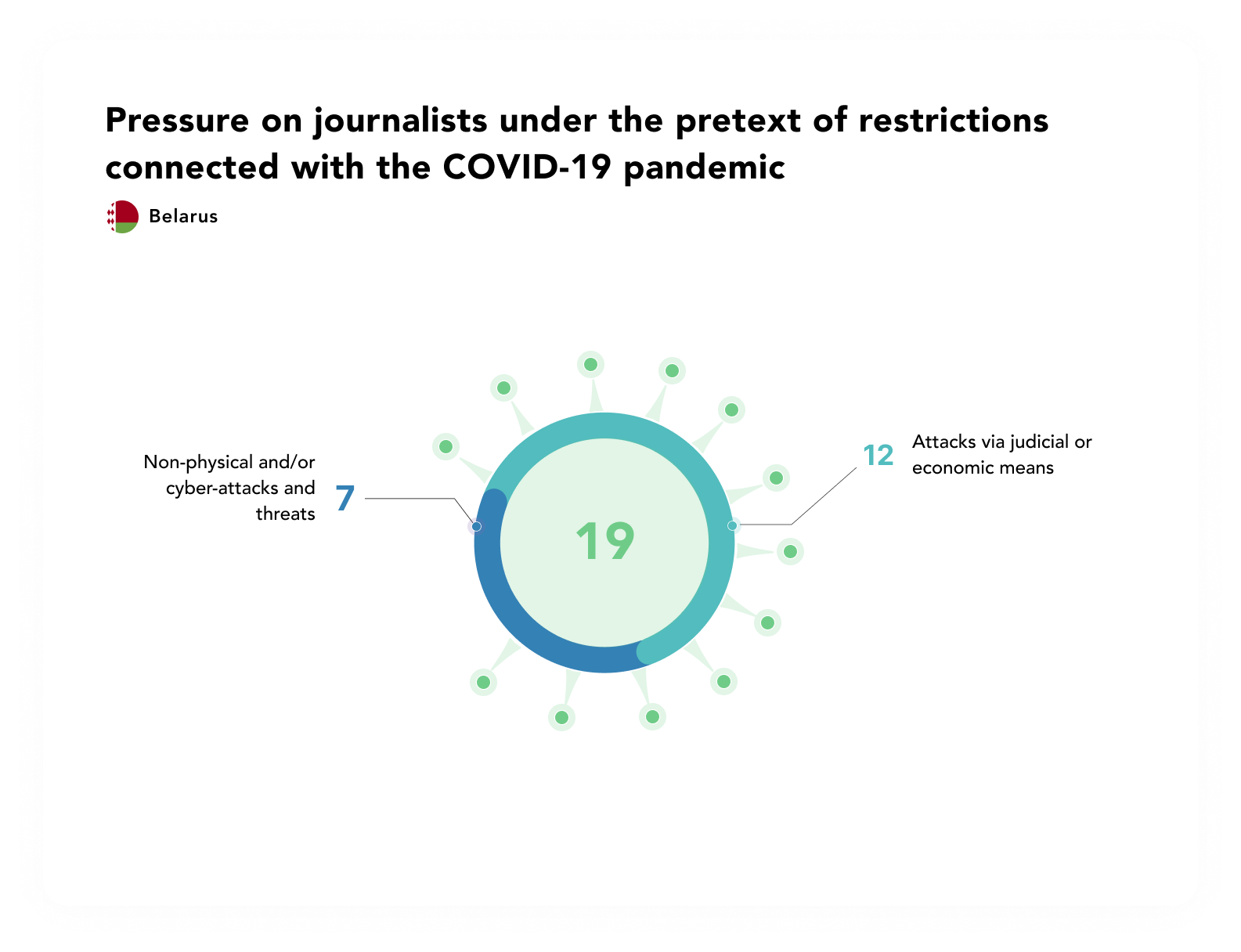

A total of 19 attacks on journalists in connection with the coronavirus were recorded: 7 non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats and 12 attacks via judicial and/or economic means. All of the attacks came from representatives of the authorities.

The most widespread method of pressure was illegal impediments to journalistic activity or denial of access to information (8 incidents), when journalists were not being allowed into hearings and/or court sessions due to quarantine restrictions (in the absence of an announced quarantine). The last briefing by the Ministry of Health for journalists at which they could pose questions to representatives of the ministry took place on 17 April. After this, the Ministry of Health has been furnishing contradictory information only through its press releases.

Another widespread method of pressure became charges of administrative violations and fines for “illegal dissemination of information in the mass information media” (5 incidents).

- On 6 April, the Ministry of Information issued the owner of the net publication Media-Polesye a written warning about violation of the law On Mass Information Media. The pretext became a publication about the spread of the coronavirus in Luninets, which contained erroneous information about the death of a patient. It is worth noting that the error was corrected 15 minutes after the appearance of the text on the site.

- On 21 April, journalists Larisa Shchiryakova [Larysa Ščyrakova] and Andrey Tolchin [Andrej Tolčyn] were served with an administrative offence report from the Homyel [formerly spelled “Gomel”] central district administration of the police for illegal dissemination of information in the mass information media. On 20 March, they had recorded a short video interview about the quarantine due to the coronavirus with students at the Francisk Skorina University. The video was used by the Belsat satellite channel.

- On 13 May, the court of Luninets District fined the editorial office of the Media-Polesye internet site 120 base values ([about 1250 euros). The court decreed that information on Media-Polesye associated with the coronavirus had inflicted harm to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus.

- On 2 June, a Homyel Region court fined independent journalist and BAJ member Larisa Shchiryakova 675 roubles. The court found her guilty under article 22.9 of the CoAV (violation of legislation on the mass information media). Serving as the reason was a photo essay for the Belsat channel from the village of Kommunar of Buda-Kashalyova District of Homyel Region, about the first case of coronavirus in a year three [third grade] pupil and the hospitalisation of 39 residents of the village – schoolchildren, their parents, teachers, and a doctor from the local polyclinic.

Three journalists had their accreditation cancelled under the pretext of the pandemic:

- On 6 May, the MFA of Belarus revoked the accreditation of journalists from the Russian Channel One Alexey Kruchinin and Sergey Panasyuk. MFA press secretary Anatoly Glaz [Anatol Hlaz] clarified that “the decision has been adopted in connection with the dissemination of information not corresponding to reality”. This took place after the appearance of a story on the situation with the coronavirus in Belarus.

- On 11 June, journalists of the leading independent news agency, BelaPAN, who had previously received accreditation for a session of the Chamber of Representatives (the lower chamber of the Belarusian parliament), had it cancelled under the pretext of the pandemic (which was officially not being acknowledged in Belarus).

5/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY AND HEALTH

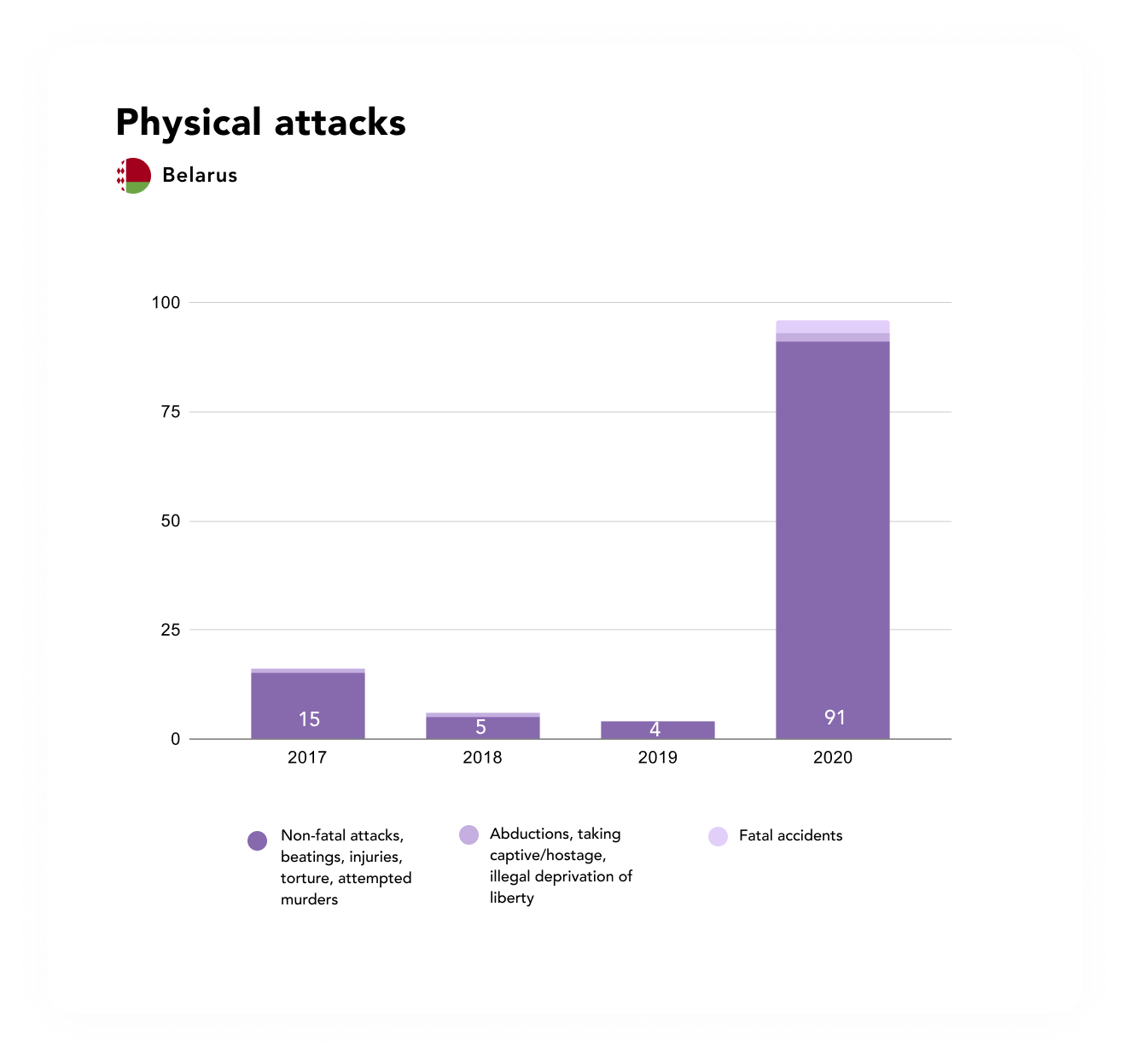

The graph below represents the total number of physical attacks and threats to life, liberty and health. The number of physical attacks on journalists in 2020 grew more than four-fold in comparison with the sum total number of such attacks over the three preceding years. The vast majority of such attacks were associated with coverage of mass protests by reporters.

Police employees were assaulting the journalists in 91 instances out of 96. Violence was used against journalists from both Belarusian and foreign media outlets, when they were executing their professional duties, as they were being detained, and in places of detention.

Three instances were recorded in Minsk of the use of firearms in relation to female journalists during work at protests, as a result of which they were wounded:

- On 9 August, Emilie van Outeren, a journalist with the NRD Handelsblad newspaper (Netherlands), was wounded in the thigh by an unknown projectile after riot police began strafing demonstrators.

- On 10 August, Nasha Niva journalist Natalia Lubnevskaya [Natallja Lubneŭskaja] was wounded by a rubber bullet when one of the employees of the law enforcement agencies stopped 10 metres from a group of journalists in blue “Press” vests and shot the journalist in the leg. Lubnevskaya spent over a month in hospital; the after-effects of the injury are still ongoing.

- On 11 August, a BelaPAN freelance journalist was wounded by a rubber bullet whilst covering a forcible dispersal of a peaceful protest.

Another three journalists – documentarians with the Neizvestnaya Belarus’ [The Unknown Belarus] project (Nastoyashchee vremya [Current Time]) Vladimir Mikhailovsky, Maksim Gavrilenko, and Lyubov Zemtsova – perished as the result of an automobile crash that occurred on 14 May on the Homyel – Minsk road. In Homyel, the documentarians had been shooting a film about how volunteers are helping medical personnel in the fight with the coronavirus.

6/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

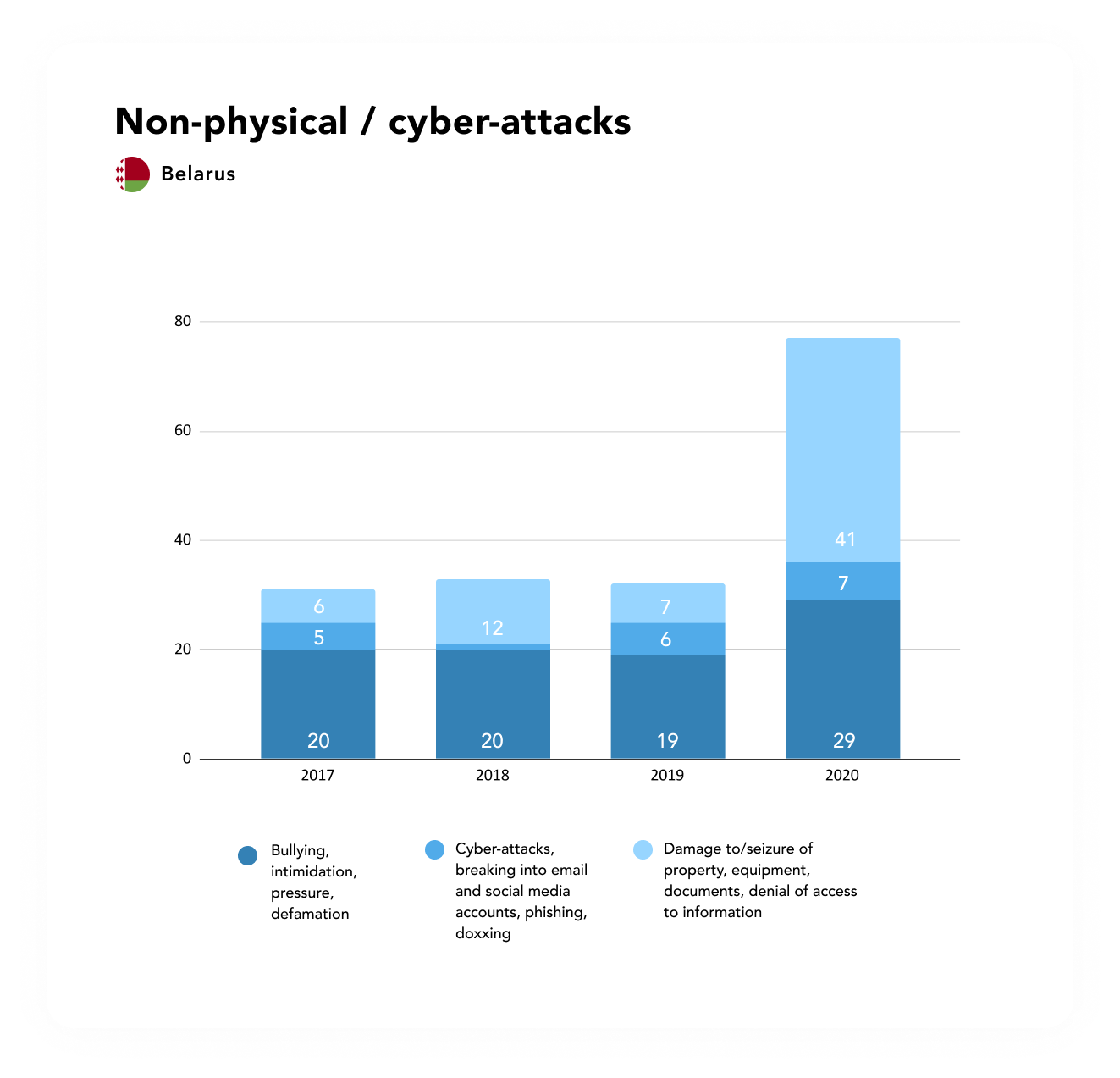

The graph below represents the total number of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats. The most widespread types of non-physical attacks and threats over the period under consideration were illegal impediments to journalistic activity (28 incidents); bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber- (27 incidents and damage to/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, printed copies of a periodical (12 incidents). The quantity of such attacks grew significantly in comparison with previous years.

7/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

Appearing as the main initiator of attacks against media outlets, journalists, and bloggers in Belarus were representatives of the authorities. They stood behind 1354 out of 1385 recorded attacks via judicial and/or economic means (84% of the incidents).

The top 5 methods of pressure on journalists in Belarus in 2020:

- short-term detention (297 incidents)

- administrative arrests/remand/pre-trial detention/prison (216 incidents)

- court trials (217 incidents)

- administrative offence, fine (175 incidents)

- confiscation/seizure of property, equipment, documents (83 incidents)

The quantity of fines for Belarusian freelance journalists working with foreign media outlets without the accreditation of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs declined somewhat – 33 (journalists were held administratively liable under this article of the CoAV 118 times in the “peak” year of 2018). This is connected above all with the fact that in the majority of the situations, instead of fines the courts were selecting another form of liability – administrative arrest for participation in illegal mass events and resisting employees of the police. Taking instances of longer-term detention in criminal cases into account, journalists and media workers spent 1200 days in aggregate behind bars in the course of the year.

- Sparking the biggest outcry was the criminal prosecution of Belsat television channel journalists Katerina [Katsjaryna] Andreyeva and Daria Chultsova for broadcasting a live stream from a mass protest event (they are charged with organising mass protests). On 18 February 2021, a court sentenced the journalists to two years in a prison colony.

- Internet portal TUT.by journalist Katerina Borisevich [Barysevič]’s “zero per mille” case became a high-profile one. She was charged with violating doctor-patient confidentiality: she had reported information furnished by a doctor that contrary to the authorities’ assertions, there was no alcohol in the blood of the dead activist Roman Bondarenko [Raman Bandarenka]. On 2 March 2021, a court sentenced the journalist to six months in a prison colony and fined her 100 base values (1000 US dollars).

- A criminal case was initiated against the investigative journalist Sergey [Sjarhej] Satsuk for supposedly receiving a bribe whilst raising funds for investigations.

- A criminal case was initiated against the managers and journalists of the “Press-club” under the pretext of the violation of tax legislation by them.

CRIMEA

Author of the report – Human Rights Centre ZMINA

1/KEY FINDINGS

58 instances of attacks/threats in relation to professional media workers and citizen journalists, editorial offices of traditional and online publications and Telegram channels, as well as online activists, that took place in 2020 on the Crimean Peninsula were identified and analysed in the course of the research. The data for the study were obtained from open sources in the Russian language using the method of content analysis, as well as with the use of the Human Rights Centre ZMINA’s own sources in Crimea (the information was checked by Centre employees). A list of the main sources is presented in the Annex 6.

- The principal method of pressure on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in Crimea is attacks via judicial and/or economic means.

- The main source of threats for media workers are representatives of the authorities (in 50 instances out of 58), while the most widespread method of pressure is charges of extremism, links with terrorists, inciting hate, rehabilitation of Nazism, high treason or calling for the overthrow of the constitutional order.

- There were 9 attacks connected with quarantine restrictions recorded in 2020. These were predominantly expressed in the actions of court bailiffs, who were not granting journalists access to politically-motivated court trials.

- There were 4 instances of physical attacks and threats to the life, liberty, and health of media workers recorded in Crimea in 2020. The given kind of attacks is no longer dominant, in contrast with 2014, when a record numberof violations of the rights of journalists with the use of force was recorded.

- The course taken by the new authorities from the moment of the occupation in 2014 to totally suppress independent journalism and establish full control over Crimea’s information space continues.

2/THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN CRIMEA

Crimea was not studied as a separate region in the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index 2020rating. In the Freedom House human rights organisation’s Freedom in the World – 2020 annual report about the situation with civil and political rights, Crimea has been included in the group of “not free countries and territories” with a score of 7 points out of 100; furthermore, a deterioration of 2 points is noted in the situation in the sphere of political rights. A situation with freedom that is worse than that in Crimea, according to Freedom House’s assessments, can be observed in only 9 countries/territories of the world, including Turkmenistan, North Korea, Tibet, Syria, and the territory of the Donbass that is not under the control of the Ukrainian authorities.

PERSECUTION OF CITIZEN JOURNALISTS

After the occupation of Crimea in 2014, the peninsula’s independent media outlets were completely destroyed. Professional journalists and editorial offices that tried to continue their work were being subjected to systematic pressure, intimidation, and other forms of systematic persecution, including harassment and other methods of attacks by the new authorities and those helping them. Many journalists left the profession or were forced to leave for the mainland part of Ukraine’s territory.

In subsequent years, the occupation forces switched to using judicial mechanisms for intimidating journalists and bloggers. This trend continued in 2020 as well.

In the conditions of an “information ghetto” and a lack of independent sources of news on the peninsula, the phenomenon of “citizen journalism” has appeared. Nowadays, it is entirely thanks to ordinary citizens and civic activists that events taking place on the peninsula are receiving coverage, especially arrests, searches, and politically motivated court trials.

One of the best-known initiatives, which has brought together many citizen journalists, is Crimean Solidarity, which was founded in 2016 through the efforts of the relatives of political prisoners, lawyers, and activists as an informal human rights organisation to protect victims of political repression. With time, the Crimean Tatar citizen journalists who were creating and disseminating news about politically motivated criminal and administrative cases in Crimea became a new target for prosecutions. Charges were brought against many of them within the framework of the “case of the Crimean Muslims” for involvement in terrorism and Hizb ut-Tahrir (an organisation that was banned in the Russian Federation by a Supreme Court decision in February 2003; however, it functions legally in Ukraine and the majority of the world’s countries). As of the end of 2020, 8 Crimean Solidarity citizen journalists find themselves in places of deprivation of liberty (Server Mustafayev, Timur İbragimov, Marlen Asanov, Seyran Saliyev, Remzi Bekirov, Ruslan Suleymanov, Osman Arifmemetov, and Rustem Şeyhaliyev); yet another one (Amet Suleymanov) finds himself under house arrest. On 21 September 2020 the Crimean Solidarity media coordinator, Crimean Tatar activist and blogger Nariman Memedeminov, who spent 2.5 years in a Russian penal settlement-colony, was released from prison.

Several trials of Crimean Tatar citizen journalists were heard in court in 2020. On 16 September 2020, the Southern District Military Court of the RF issued a verdict in the so-called case of the “second Bağçasaray [also spelled “Bakhchysarai”] Hizb ut-Tahrir group”, the figurants in which were found guilty of preparing a forcible seizure of power and participating in the activity of a terrorist organisation. The defendants in this case included 4 citizen journalists from the Crimean Solidarity civic association: Server Mustafayev was sentenced to 14 years of imprisonment in a strict regime colony, Seyran Saliyev to 16 years, Timur İbragimov to 17 years, and Marlen Asanov to 19 years.

In December, the Southern District Military Court of the RF began hearing the so-called case of the “second Simferopol Hizb ut-Tahrir group”, the members of which are being charged with preparing a forcible seizure of power and participating in the activity of a terrorist organisation. The defendants in this case include 4 citizen journalists from the Crimean Solidarity civic association: Remzi Bekirov, Osman Arifmemetov, Rustem Şeyhaliyev, and Ruslan Suleymanov.

BLOCKING OF UKRAINIAN MEDIA OUTLETS

The situation regarding the blocking of access to a whole series of Ukrainian media resources on the territory of Crimea remained unchanged in 2020. According to the data of a Crimean human rights group, a minimum of 11 providers in 9 Crimean population centres have completely blocked 20 Ukrainian media websites: Ukrinform,Censor.net, QHA Crimean News Agency, SLED.net.ua, Information Resistance, UAinfo, BlackSeaNews, Apostrophe, Glavnoe, Hromadske Radio, Centre for Journalistic Investigations, Levyy Bereg [LB.ua], Podrobnosti, Strichka, ToNeTo, TSN, Ukrayinskapravda, RBK Ukrayina, Dzerkalo Tyzhnia [Mirror Weekly], and Kherson Daily. Additionally, some providers are blocking another 4 Ukrainian media outlets: the Glavcom, 5 Kanal, 112 Ukraine, and Depo websites are inaccessible through nine out of eleven providers. It is worth noting that some of these resources are accessible for users in Russia. Additionally, reception of the signal of Ukrainian FM radio stations in the north of Crimea has worsened significantly, while in many population centres Russian radio stations are broadcasting on these frequencies.

Representatives of the occupation authorities continue to regard independent sources of information on the territory of Crimea as a threat and as the adversary’s tools in an information war, while considering the principal task of media outlets in the region to be a defence against “enemy” distortion of the facts.

LEGISLATIVE REGULATION OF THE ACTIVITY OF MEDIA OUTLETS AND JOURNALISTS

A whole series of new normative-legal acts, the effects of which extend to the territory of Crimea, were adopted in the Russian Federation in 2020.

On 1 April 2020, president Vladimir Putin signed a law that introduces new articles to the Criminal Code: 207.1 (“public dissemination of knowingly false information about circumstances presenting a threat to the life and safety of citizens “) and 207.2 (“public dissemination of knowingly false socially significant information entailing grave consequences”). Falling under the norms of these articles is information about measures being undertaken to ensure security in the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to this, in the Code on Administrative Offences, article 31.15 (“abuse of freedom of mass information”) was supplemented by two items: “dissemination of knowingly unreliable information about circumstances presenting a threat to the life and safety of citizens” (item 10.1) and “dissemination of knowingly unreliable information entailing death, harm to health, mass breach of security” (item 10.2).

Changes to the law “On the federal security service” [the FSB] entered into force on 1 August; its article 7 now has the language: “Publication (posting, dissemination) of informational materials, concerning the activities of bodies of the federal security service, without a corresponding opinion from a body of the federal security service shall not be permitted.” It can not be said with confidence from the general context of the article whether this restriction is only for FSB employees or if it extends to all citizens.

Amendments to article 280.1 of the Criminal Code (“public calls for implementing acts aimed at violating the territorial integrity of the Russian Federation”) entered into force on 8 December;prescribing administrative prejudgment and the onset of criminal liability in the event of a repeat violation over the span of a year. A new article, 20.3.2 on “calls for separatism”, prescribing punishment in the form of fines, was introduced into the Code on Administrative Offences at the same time.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

38 attacks via judicial and/or economic means, 16 non-physical and/or cyber-attacks, and 4 physical attacks were identified in the course of the research.

Physical attacks were not dominant in 2020, in contrast with 2014, when the greatest quantity of violations of the rights of journalists with the use of force were committed. Thus, more than 100 instances of physical attacks on journalists were recorded during the active phase of the armed occupation from 26 February through 22 March 2014, including beatings, abductions, and torture. Arbitrary detentions, damage to property, prohibition of video shoots and denial of access to the peninsula, as well asvarious threats and intimidations, took place as well. Such acts were perpetrated primarily by paramilitary formations of “Cossacks” and “militias” under the control of the RF.

4/ PRESSURE ON JOURNALISTS UNDER THE PRETEXT OF RESTRICTIONS CONNECTED WITH THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

A “state of high alert”, not prescribed in legislation, has been introduced in Crimea as of 17 March 2020 in connection with the pandemic. The set of restrictions within the framework of this state has been changed on numerous occasions, and a series of prohibitions continues to be in effect to this day.

On 3 April, within the framework of the “state of high alert”, everyone except life-support services workers was prohibited from leaving their place of residence. An exception was made for journalists from the pro-government Krym television channel. Journalists from other registered media outlets having the opportunity to draw up official editorial assignments received the right to leave their place of residence on 14 April. Bloggers, citizen journalists, and non-staff employees of media outlets were restricted in the right of movement until 18 May 2020.

On 10 June, by decree of the “Council of Judges of the Republic of Crimea”, access to court sessions was completely ruled out for persons who are not participants in the trial. As such, journalists were deprived of the opportunity to cover socially significant court trials, including political and religious persecutions, as well as examinations in environmental damage cases. This restriction continues to be in effect to this day; that being said, judges can establish the quantity of journalists for whom it is permitted to be present as attendees at their own discretion.

9 attacks connected with quarantine restrictions were recorded in 2020. All of them consist of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats. They were predominantly expressed in the actions of court bailiffs, who were not granting journalists access to politically motivated court trials, citing coronavirus restrictions.

- On 24 March, the press service of the head of Crimea asked representatives of the mass information media to temporarily restrict visits to the Council of Ministers due to the situation with the coronavirus. Despite the recommendatory character of the request, access for journalists to the Council of Ministers building was terminated and has not been reinstated to this day.

- On 19 and 22 May, two sessions took place in the Central District Court of Simferopol in the case of former political prisoner Edem Bekirov, released in an exchange and subsequently declared a wanted fugitive. Bailiffs announced to a Crimean Process journalist and other attendees at the entrance to the courthouse that only participants in the trial were being let into the building in connection with measures to prevent the spread of the coronavirus infection.

- On 26 June, an examination took place in the Kiev District Court of Simferopol of a complaint by lawyer Nikolai Polozov, a motion for whose dismissal had been brought by an investigator in a criminal case in relation to the head of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, Refat Çubarov. Bailiffs announced to a Crimean Process journalist and other attendees at the entrance to the courthouse that only participants in the trial were being let into the building.

- On 19 October, a repeat examination of a criminal case in relation to a participant in the Jehovah’s Witnesses religious community, Viktor Stashevsky, began in the Gagarin District Court of Sevastopol. Bailiffs announced to a Crimean Process journalist and other attendees at the entrance to the courthouse that only participants in the trial were being let into the building.

5/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

4 physical attacks and threats to the life, liberty, and health of media workers were recorded in 2020, including two instances of the use of punitive psychiatry and two non-fatal attacks in the course of a conflict situation with a Krym 24 television channel camera crew.

- It became known on 24 June that Crimean Solidarity citizen journalist Ruslan Suleymanov had been forcibly sent to the Crimean Psychiatric Hospital for the conducting of a forensic psychiatric evaluation. Suleymanov spent no less than a month in the psychiatric hospital.

- On 26 October a Krym 24 camera crew (journalist Dmitry Popov and camera operator Maxim Savenkov) entered onto the territory of a private housing estate in search of the owner of an illegal building site in a nature reserve. A man lunged at the journalist, and then inflicted several blows to the camera operator and damaged the video camera. Later the assailant caught up with Popov and Savenkov and was throwing stones.

- On 16 January, Crimean Solidarity citizen journalist Rustem Şeyhaliyev was forcibly sent to the Crimean Psychiatric Hospital for the conducting of a forensic psychiatric evaluation. Şeyhaliyev spent no less than a month in the psychiatric hospital.

6/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER ATTACKS AND THREATS

The most widespread method of pressure on media workers, bloggers, and online activists is illegal impediments to journalistic activity, denial of access to information (12 incidents, 9 of which are attacks connected with restrictions within the framework of quarantine measures). In 11 instances out of 16, the attacks came from representatives of the authorities.

Illegal impediments to journalistic activity, denial of access to information was expressed primarily in the actions of court bailiffs and the conducting of trials behind closed doors.

- On 24 April, during the filming of a story about illegal construction inside the boundaries of the Qaradağ nature reserve, a camera crew from the Vesti Krym television channel encountered attempts by the site’s security to prohibit the shoot and threats to block the camera operator’s movements.

- On 27 October, examination began in Crimea’s Kirov District Court of a criminal case in relation to a participant in the Asker volunteer organisation, Mecit Ablâmitov. Bailiffs at the entrance to the courthouse announced to a Crimean Process journalist and other attendees that the session was going to take place behind closed doors. They refused to let the journalist enter the building. All further sessions in the case were likewise taking place without the participation of attendees and journalists.

- On 2 September, an appellate complaint against a measure of restraint in relation to the participant in the Asker volunteer organisation Mecit Ablâmitov was examined in the Supreme Court of Crimea. Bailiffs at the entrance to the courthouse announced to a Crimean Process journalist and other attendees that the session was going to take place behind closed doors. They refused to let the journalist pass through into the building for the reading of the court decree.

Likewise noted were single isolated cases of attacks such as “bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber-“, “breaking into email/social media accounts/computer/smartphone”, “defamation, spreading libel about a media worker or media outlet”, and “damage to/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials, print run”.

- On 18 November, a publication without a byline appeared on the Novoros.info publication’s website, in which editor of the Crimean Tatar newspaper Qırım Bekir Mamut was called a supporter of a banned organisation and a radical and was accused of publishing anti-Russian articles, as well as doubt being cast on the legality of the activity of the Qırım publication in Crimea.

- On 24 November, after a three-day absence of publications on the Zorro iz Kryma [Zorro from Crimea] Telegram channel, a report appeared about how the authors of the social media channel had been “revealed, identified, and conducted educational work” [sic], while all their correspondence with sources of information had been “documented”. Contained in the report was a call addressed to “all who have not passed the point of no return” to come to their senses. After this the channel stopped being updated.

7/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

The principal methods of pressure in the given category are charges of extremism, links with terrorists, inciting hate, high treason, calling for the overthrow of the constitutional order, rehabilitation of Nazism (12), short-term detention (5), and court trials (5).

Blocking of Ukrainian online publications (including Crimean media outlets working in exile on the mainland part of Ukraine) and FM radio stations continued throughout the course of 2020. Thus, monitoring of access to internet resources in December 2020 conducted by a Crimean human rights group among 11 of Crimea’s internet providers showed that a minimum of 25 Ukrainian websites were being fully blocked, and another 5 partially (in individual districts and/or by individual operators). Monitoring of FM band broadcasting in the north of Crimea showed that the signal of Ukrainian radio stations is accessible in only 7 out of 19 population centres. Blocking of signals is implemented by way of broadcasting Crimean and Russian radio stations on the frequencies of Ukrainian broadcasters.

Attacks on Crimean citizen journalists and bloggers by means of visits to them at home by employees of the law-enforcement agencies became more frequent in 2020. Cautions about the impermissibility of extremist acts were read out in the course of such visits (8 incidents). It was being asserted that it was supposedly known with certainty to the police that that or the other journalist was an organiser of or participant in planned disorders and other extremist actions.

- On 25 March, blogger Rolan Osmanov received a “warning about the impermissibility of extremist activity”. What was being spoken of in the caution was that supporters of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, which is banned in the RF, were planning to conduct unapproved mass events in this period.

- On 26 March, in Nizhnegorsk, cautions about the impermissibility of extremist acts were issued to at least 10 Crimean Tatars. Among them was the citizen journalist with Crimean Solidarity Ayder Kadyrov, who was detained 5 months later as a suspect in a criminal case related to terrorism.

- On 2 April, a police employee drove to Crimean Solidarity citizen journalist Nuri Abdureşitov‘s home and was trying to conduct an interrogation, and later read out a caution about the impermissibility of extremist activity to the journalist.

- On 17 April, three Crimean Solidarity citizen journalists from different regions of Crimea —Kulamet İbraimov, Emin Rustemov, and Nuri Abdureşitov— received cautions from law-enforcement agencies about the impermissibility of extremist activity. Rustemov and Abdureşitov noted that they had already received such cautions earlier.

- On 21 April, a field operative drove up to the home of Elmaz Akimova, a citizen journalist with the Nefespublication, conducted questioning about the place of her work and plans for the immediate future, and posed a series of other questions, after which he served her with a caution about the impermissibility of extremist acts.

- On 1 May, police precinct employee Vladislav Sadovoy served citizen journalist Lutfiye Zudiyeva with two cautions about the impermissibility of extremist acts. Zudiyeva subsequently appealed these acts in court, and during the time of the examination MVD [Ministry of Internal Affairs] employees could not substantiate the necessity of such a caution.

Court trials on charges of terrorism have likewise been one of the widespread methods of pressure on citizen journalists, bloggers, and online activists in Crimea over the span of recent years (5 incidents in 2020). All criminal cases such as these, in relation to citizen journalists, end with guilty verdicts. The charges in these cases are preceded by searches, detentions, interrogations, arrests, and often forced forensic psychiatric evaluations with the persons under investigation being held in psychiatric treatment institutions for a lengthy period of time.

- On 11 March, searches took place in the homes of five Crimean Tatar families in Bağçasaray [Bakhchysarai], including the house where Crimean Tatar television channel ATRC journalist Seytumer Seytumerov previously resided. FSB employees consider him to be the organiser of a terrorist cell, but the journalist himself asserts that the accusations are baseless. During the time of the first search in 2017 no charges were brought against him, and after that he was able to leave Crimea.

- On 11 March, a search was likewise conducted in the home of Crimean Solidarity citizen journalist Amet Suleymanov. The next day a measure of restraint in the form of house arrest was selected for Suleymanov in a case of “participation in the activity of a terrorist organisation”. The measure was subsequently extended on several occasions.

- On 11 March, the Kiev District Court of Simferopol extended the measure of restraint in the form of detention for citizen journalist Remzi Bekirov of the Crimean Solidarity association. In the course of the session it became known that an additional charge had been laid against Bekirov under article 278 of the Criminal Code (“violent seizure of power”). Bekirov has been in detention since 28 March 2019. He is being charged under part 1 of article 205.5 of the CC (“organisation of the activity of a terrorist organisation”).

- On 23 March, the Supreme Court of the Republic of Crimea extended the measure of restraint in the form of detention for Crimean Solidarity citizen journalist Osman Arifmemetov, who had earlier (in March 2019) been charged with having taken part in a terrorist organisation. In the course of the session it became known that an additional charge had been laid against him under article 278 of the CC (“violent seizure of power”).

- On 17 December, a preliminary court session began in Crimea’s Nizhnegorsk District Court in a criminal case in relation to Crimean Solidarity citizen journalist Ayder Kadırov, who had been charged with failure to report a crime for a supposedly existing correspondence with a member of the ISIS terrorist grouping. The start of the court trial was preceded by a restriction on leaving the region. Before this, on 3 August, Kadırov was detained for 15 hours and was interrogated in the absence of a lawyer.

6 instances of unjustified short-term detentions of journalists and bloggers were recorded. The detentions were likewise frequently accompanied by searches and administrative offence reports.

- On 30 October, after an unsanctioned search in his house, blogger Ilya Bolshedvorov was delivered to a police station for the drawing up of an administrative offence report for a single-person picket that the blogger had been shooting video of on a mobile telephone.

- On 3 November, Crimean Solidarity citizen journalists Vilen Temeryanov and Ablâmit Ziyadinov, who were filming a protest at the Crimean Garrison Military Court building, were detained outside the courthouse by police employees and delivered to the “Central” Department of Internal Affairs [police station – Trans.]. As a result, two administrative offence reports were drawn up in relation to Temeryanov — under part 5 of article 20.2 of the Code on Administrative Offences (“violation by a participant in a public event of the established order for conducting a meeting, rally, demonstration, march, or picketing”) and under article 20.6.1 (“non-observance of the rules of conduct after the introduction of a state of high alert”). On 28 December, police employees detained Vilen Temeryanov outside his house in order to deliver him to court for the examination of an administrative case pursuant to the report drawn up on 3 November.

KAZAKHSTAN

An independent expert opinion about Attacks on media workers in Kazakhstan report

Despite Kazakhstan’s regular efforts to demonstrate democratic changes, the situation with journalistic freedoms remains dismal. Cosmetic amendments to legislation unfortunately do little to promote real reforms, while media workers find themselves under a constant onslaught of pressing.

The period from 2017 through the year 2020 was intense and dramatic for Kazakhstani journalists: a several-times “patched up” law on the mass information media, changes to normative legal acts regulating the activity of the press, claims for huge sums made in cases of defamation, and the old tried and true methods of influencing the press – threats and intimidation.

Although 90% of the media in Kazakhstan take positions in support of the ruling power and are dependent on state bodies, the old-fashioned, weak, and inefficient government continues to fear the utterance of free thoughts. It is precisely for this reason that government officials remain the main threat to the media – the number of assaults and attacks on journalists is not falling, but rising.

As has been rightly noted in the report, the methods of attacks in recent years have changed. Today the bodies of state prefer to “avoid needless bloodshed”, using judicial and economic means in relation to the media. With the development of the internet and the migration of part of the audience there, blocking of websites has begun to be applied more frequently, which represents not only a restriction of citizens’ right to access to information, but also an attack on free expression of opinion. Blocking “for no reason”, when not a single state agency takes responsibility for having restricted access to a website, has acquired particular popularity in Kazakhstan. All the while there are no official violations and charges, and yet the website remains blocked. In the opinion of human rights advocates, the motives for such blocking are political.

The pandemic of 2020 exacerbated practically all of the problems in the mediasphere. The situation with access to information deteriorated significantly; as before, many court cases are connected with publications on the internet. Online briefings and press conferences afford the opportunity for state agencies to duck questions, interrupt journalists, and limit their participation. The same thing concerns court trials as well. Such incidents represent a real threat for journalists inasmuch as they impede their professional activity.

The adoption of a law on peaceful rallies has transformed the Kazakhstani practice of control over the mass media somewhat. In 2020 state bodies changed the tactic of detention: now journalists and activists are simply rounded up in a circle and held there for hours – a practice that has received the name “kettling”. As a result, representatives of the media are not subjected to physical beatings, but are deprived of the opportunity to carry out their professional duty.

Nor can we fail to mention self-censorship as well. The articles of the Criminal Code on inciting hate and disseminating knowingly false information are rarely applied in relation to journalists, but they do serve as a deterrent factor during the publication of investigations and hard-hitting materials.

In recent years citizen journalists and bloggers have started getting subjected to threats more frequently – to cyber-threats as a rule. That being said, the registered media also continue to experience difficulties connected with repressive legislation, dependence on state agencies, and political pressure.

A series of NGOs are working in Kazakhstan, rendering legal aid to journalists and bloggers, consulting, teaching, and lobbying the government on the urgent questions facing the media community. It ought to be noted that their activity has been quite effective in some spheres. Thus, with the active participation of NGOs, amendments were adopted to the law on the mass information media concerning protection of the rights of children, libel has been decriminalised, and appropriate language has been used in the law on peaceful rallies concerning the participation of journalists.

Diana Okremova,

Director, OF Legal Media Centre (Astana)

Author of the Report – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech

1/ KEY FINDINGS

342 instances of attacks/threats in relation to professional media workers and citizen journalists, and editorial offices of traditional and online publications, as well as online activists in Kazakhstan in 2020 were identified and analysed in the course of the research. The data for the research were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Kazakh, and English languages using the method of content analysis. A list of the main sources is presented in the Annex 7.

- The main type of attacks in relation to media workers, as well as bloggers and online activists, is attacks via judicial and/or economic means.

- The main source of threats for media workers, bloggers, and online activists in Kazakhstan are representatives of the authorities, while the most widespread methods of attacks on media workers and civilian journalists in this category are court trials, charges in administrative offence cases, summonses for interrogations, and short-term detentions.

- Mass short-term detentions are directly connected with the growth in protest sentiments in society. Short-term detentions of journalists take place in the course of their coverage of mass protests in the large cities of Kazakhstan.

- The second most popular type of attacks in relation to traditional media journalists and civilian journalists (according to openly available statistics) are non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats, especially illegal impediments to journalistic activity and denial of access to information. The main source of threats in this category are likewise representatives of the authorities.

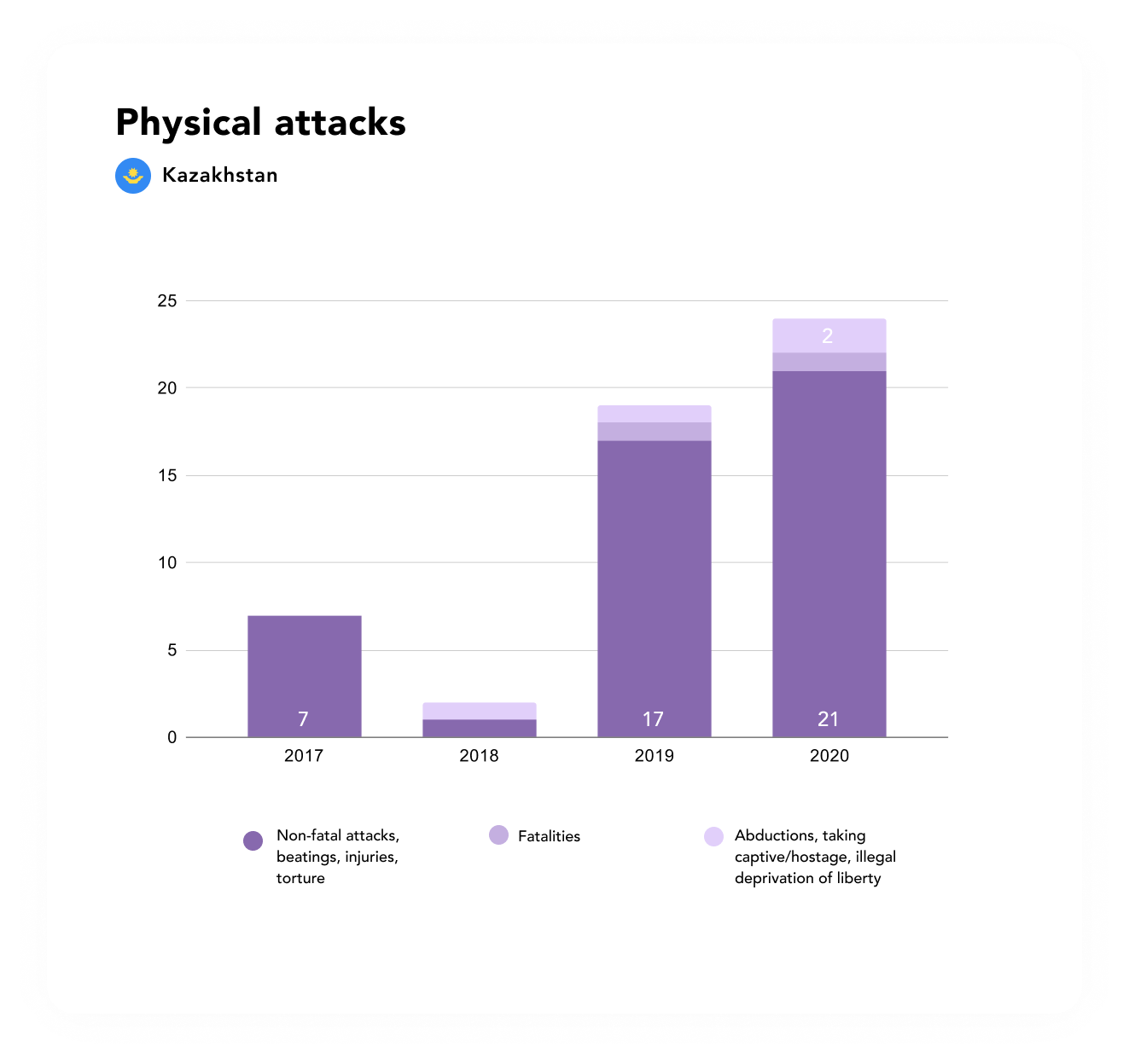

- 24 instances of physical attacks and threats to the life, liberty, and health of media workers were recorded in 2020 (for comparison: there were 19 such attacks in 2019).

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN KAZAKHSTAN

Kazakhstan has improved its position in the Reporters Without Borders 2020 World Press Freedom Index, having taken 157th place out of 180 (the country held 158th place in the rating for 2019). In the Freedom House human rights organisation’s annual Freedom in the World 2020 report about the situation with civil and political rights, Kazakhstan, with a score of 23 points out of 100, remains in the category of “unfree countries”, as it had been in the previous year (22 points out of 100).

It is possible that some improvement in the country’s position in the ratings is associated with the long-awaited decriminalisation of libel. In December 2019, the president made an announcement about a decision to remove libel from the ranks of criminal offences. On 10 July 2020, a law entered into force whereby libel was moved from the Criminal Code to the Administrative Code.

According to the data of the Ministry of Information and Social Development, as of 19 October 2020 there were 4597 media outlets registered in Kazakhstan, of which 3432 comprise periodical publications, 175 are television channels, 74 are radio, and 660 are news agencies and online publications. There are 256 foreign television channels registered on the list of media outlets.

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC AND THE STATUS OF THE MEDIA

A state of emergency was introduced in Kazakhstan as of 16 March 2020 in connection with the pandemic. It was extended several times and ended on 11 May. However, quarantine restrictions of various degrees of severity continue to this day.

As of 16 March, the head state sanitary doctor [chief public health officer ‒Trans.] introduced a prohibition on audio, photo, and video shoots in health care organisations, ambulances, in quarantined premises, and during the rendering of in-home medical assistance by medical workers and the conducting of epidemiological research in a focus of infection. Both interview and questionnaire surveys of patients and of “contacts” were prohibited. The prohibition became the reason for the detaining of KTK television channel journalists in Atyrau Region on 11 April.

In the conditions of the state of emergency and quarantine, all sessions of state bodies are being conducted remotely via online means. Online transmissions of sessions take place with disruptions. In response to journalists’ complaints with respect to the bad quality and disruptions of the online transmissions, the officials responsible for ensuring access to information cite technical problems.

At briefings and press conferences, the majority of which take place online, journalists, who are obliged to send in their questions in advance, encounter a situation where the moderators pose only the “convenient” questions to the spokespersons.

In the period that the state of emergency and quarantine regime has been in effect, the most defenceless category of journalists have become bloggers, whose status is not defined in any way in Kazakhstan’s legislation. It is specifically bloggers and online activists who are most frequently charged with libel and with violating the state of emergency regime.

Kazakhstan’s mass media outlets have encountered economic hardships as a result of the pandemic. This especially concerns the print media, which has been deprived of the opportunity not only to distribute print runs among subscribers, but also to sell them in retail outlets and specialised kiosks. According to the official data, the forecast loss of advertising incomes in 2020 sits between 30% and 60%.

ELECTIONS TO THE LOWER CHAMBER OF PARLIAMENT AND LOCAL EXECUTIVE BODIES: LEGAL AND NORMATIVE ACTS AND THE STATUS OF THE MEDIA

On 21 October, the president of Kazakhstan made an announcement about upcoming regular elections to parliament and local executive bodies. The elections were scheduled for 10 January 2021.

On 4 December, the Central Electoral Commission published a decree defining the rights and duties of candidates’ agents, observers, and representatives of the media. Representatives of NGOs, civic activists, and journalists declared that this document seriously restricts the opportunity to independently observe the elections. In particular, the items about the prohibition on video transmission from polling stations, about the need to get citizens’ approval to use their images, and about how only those legal entities that have this activity explicitly included in the organisation’s charter can send observers to the elections were subjected to criticism.

In addition to this, mass media outlets were prohibited from conducting pre-election surveys without fulfilling a series of conditions: they must notify the Central Electoral Commission in advance, confirm that they have five years of experience conducting surveys, and have employees with a sociological education and employment history on staff.

A “Checklist for mass information media and journalists in the period of elections in the Republic of Kazakhstan” issued by the relevant ministry prescribes “refraining from the publication of agitational materials and other information knowingly tarnishing the honour, dignity, and business reputation of a candidate or political party” and reminds about civil and criminal liability.

With the start of the pre-election campaign, bloggers and online activists began to be called to the prosecutor’s office in connection with surveys on the topic of the elections; they were warned about administrative liability for violating electoral legislation. Thus, in December the blogger Kairat Abdrakhman [“Qairat Äbdırahman” in Kazakh] (Almaty Region) was fined by a court for a survey published on social media on 9 November. The blogger had expressed interest about whether or not his subscribers trusted the elections and what they thought about the deputies to the city mäslihat [members of the city council ‒ Trans.].

A requirement that agents, observers, and representatives of the media present at polling stations strictly comply with safety measures and maintain social distancing of no less than one and a half to two metres was introduced on 29 December by decree of the head state sanitary doctor.

LEGISLATIVE REGULATION OF THE ACTIVITY OF MEDIA OUTLETS AND JOURNALISTS

Laws significant to society, in particular about rallies and about the decriminalisation of libel, were discussed and adopted in Kazakhstan in 2020 without the participation of the public.

A law “On the introduction of changes and additions to some legislative acts of the RK with respect to questions of enforcement proceedings and criminal legislation”, removing the “Libel” article from the Criminal Code, entered into force on 10 July. Libel is being moved to the Code of the RK “On administrative offences” and prescribes a fine or administrative arrest with a maximum term of up to 30 days. With the decriminalisation of libel, the quantity of criminal cases in relation to journalists declined insignificantly. Human rights advocates continue to insist on moving libel into the sphere of civil law: administrative proceedings infer the participation of the state and the police.

On 25 May, the president of the RK signed a law “On the order for organising and conducting peaceful gatherings in the Republic of Kazakhstan”. A norm about the duty of a journalist or an organiser and a participant in a peaceful gathering to turn over a photo shoot or video recording of peaceful gatherings at the demand of state bodies and/or official persons thereof did not make it into the final version. Likewise removed were norms about the rights and duties of a journalist that replicate the law on the mass information media. The law entered into force on 6 June 2020.

On 30 December, the president of Kazakhstan signed a law “On the introduction of changes and additions to some legislative acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan on questions of information”. These changes are aimed at resolving two main tasks – strengthening control and responsibility and expanding the sphere of application of the law. In the opinion of journalists, the law does not expand access to information for media employees, citizens, and non-governmental organisations. According to this new law, a journalist may be stripped of accreditation for violating the rules of accreditation: i.e. furnishing an incomplete package of documents, incorrectly filling out an application, a court decision on suspending/terminating the activity of a media outlet, and for spreading information that does not correspond to reality and tarnishes the business reputation of the state bodies that had accredited it and civic associations and organisations, as well as upon application by an owner of a media outlet or an editorial office. It is not indicated in the law who is going to determine that that or the other information does not correspond to reality and is tarnishing the business reputation of state bodies.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

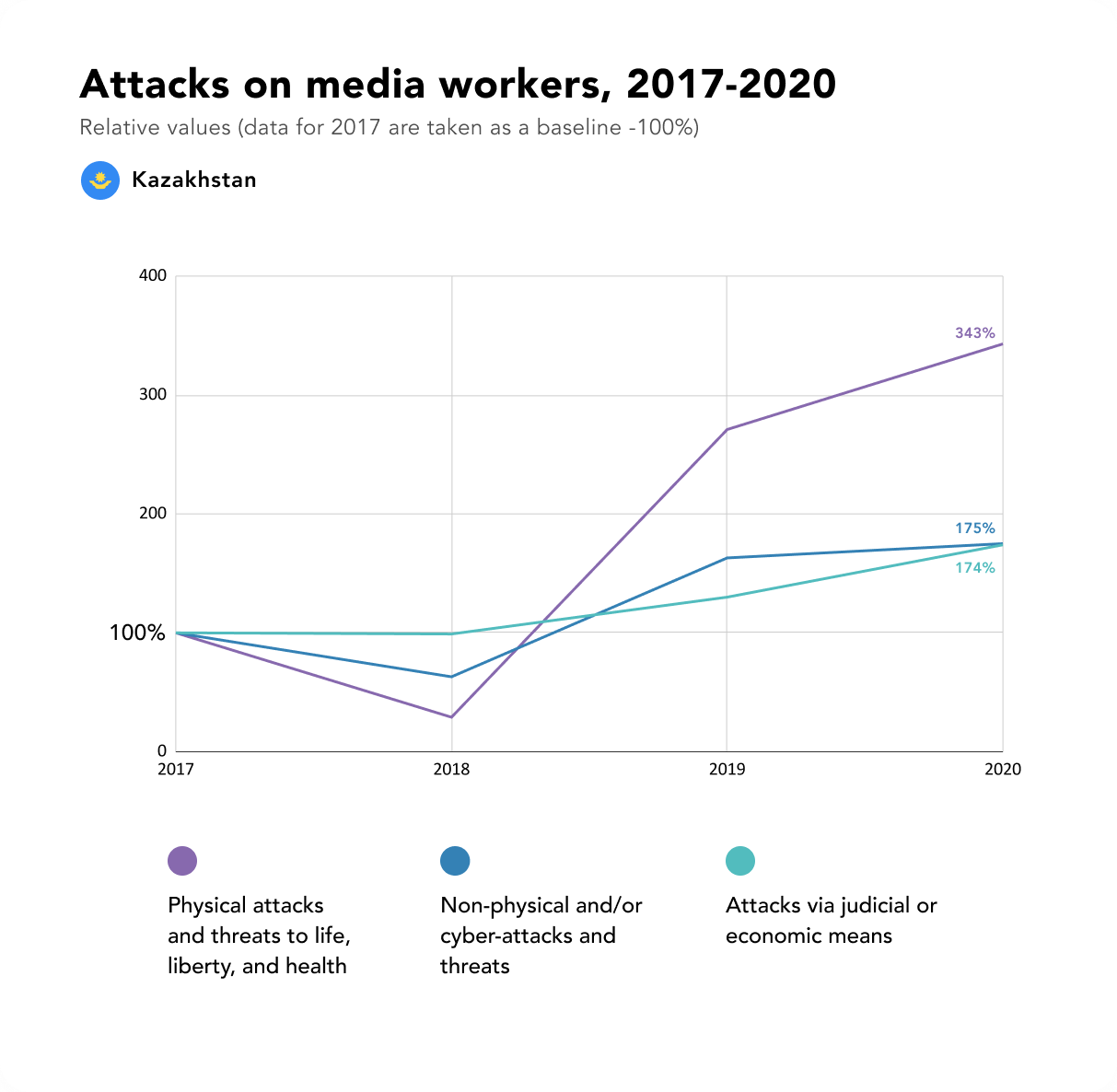

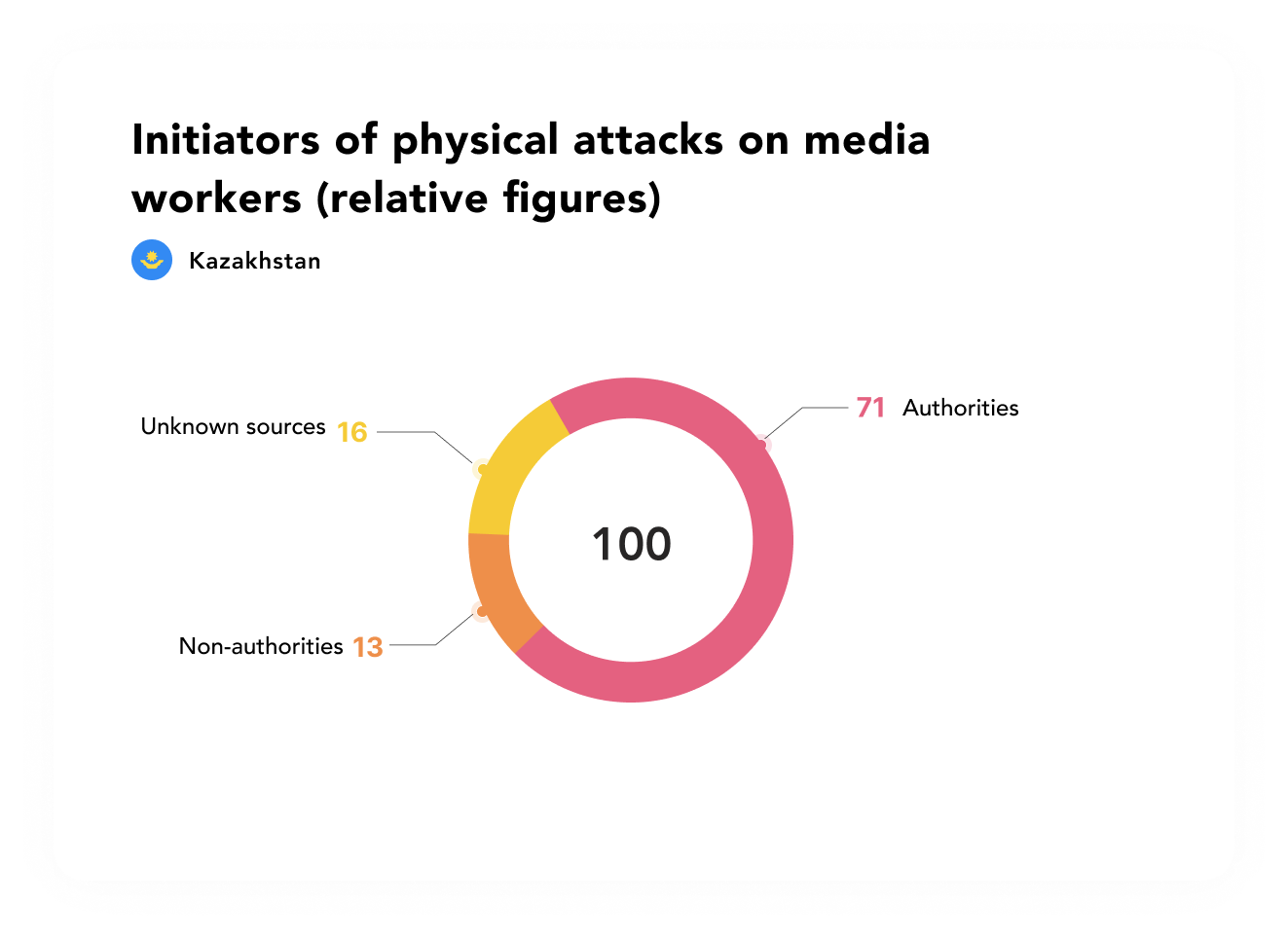

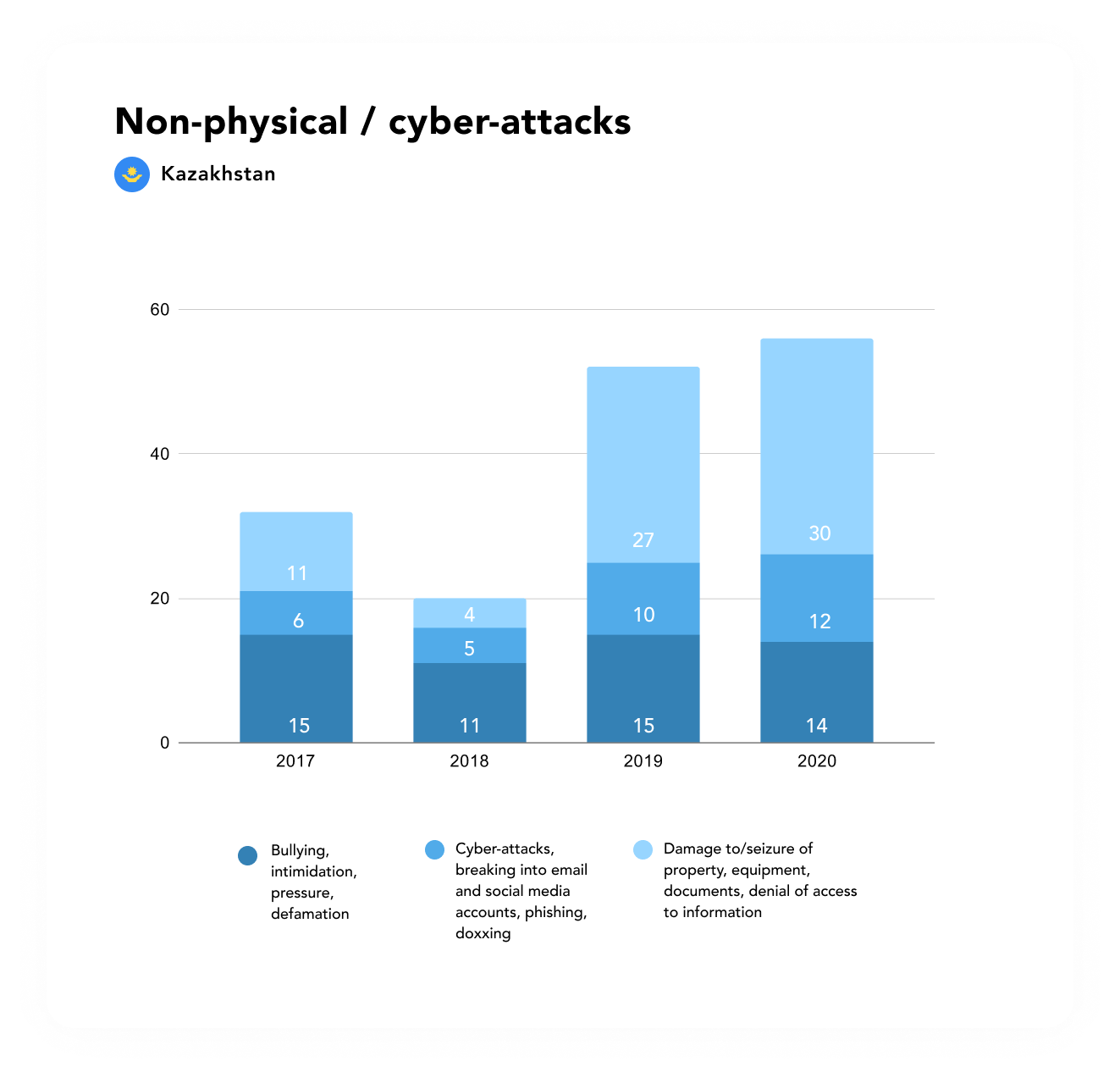

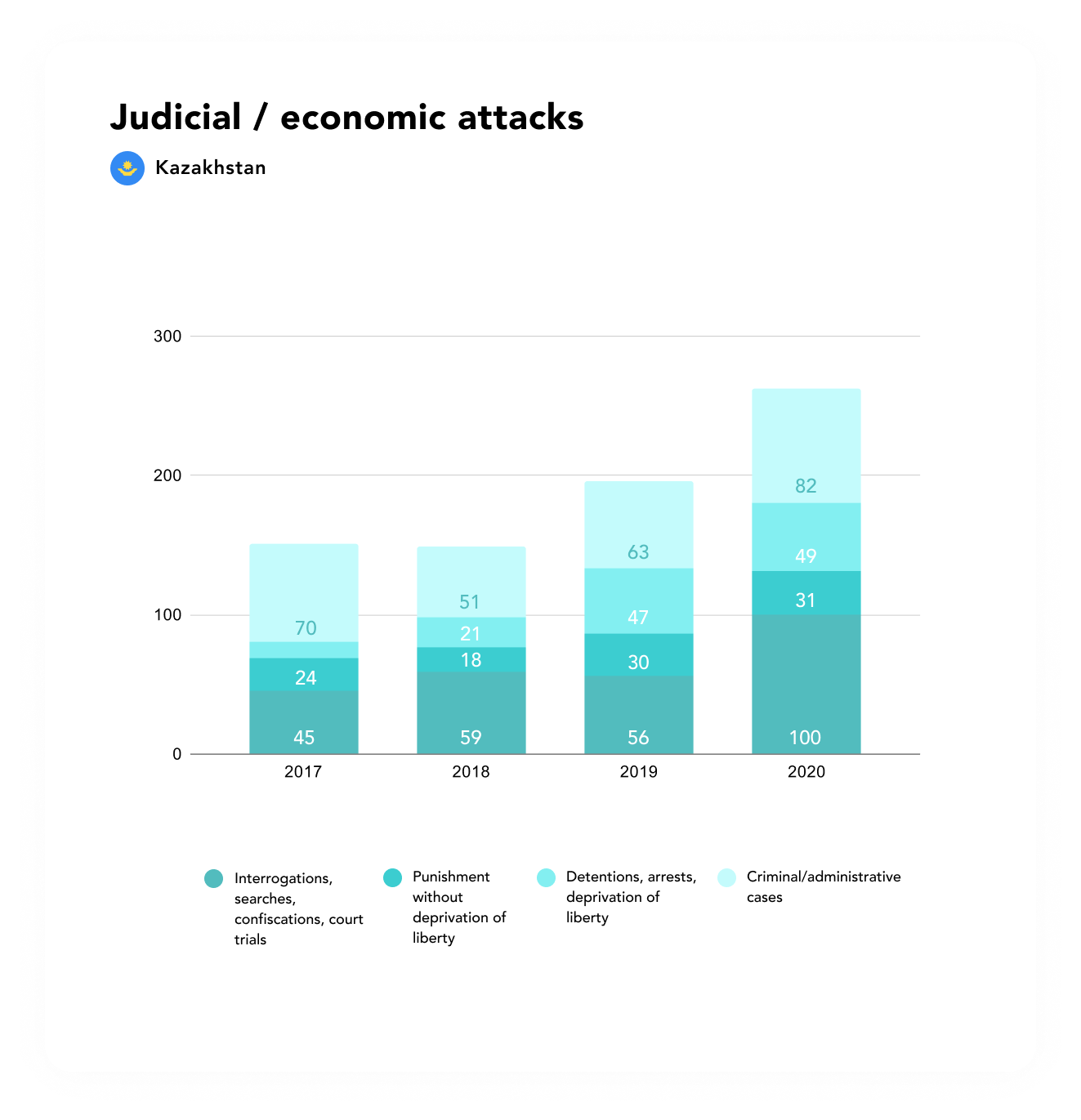

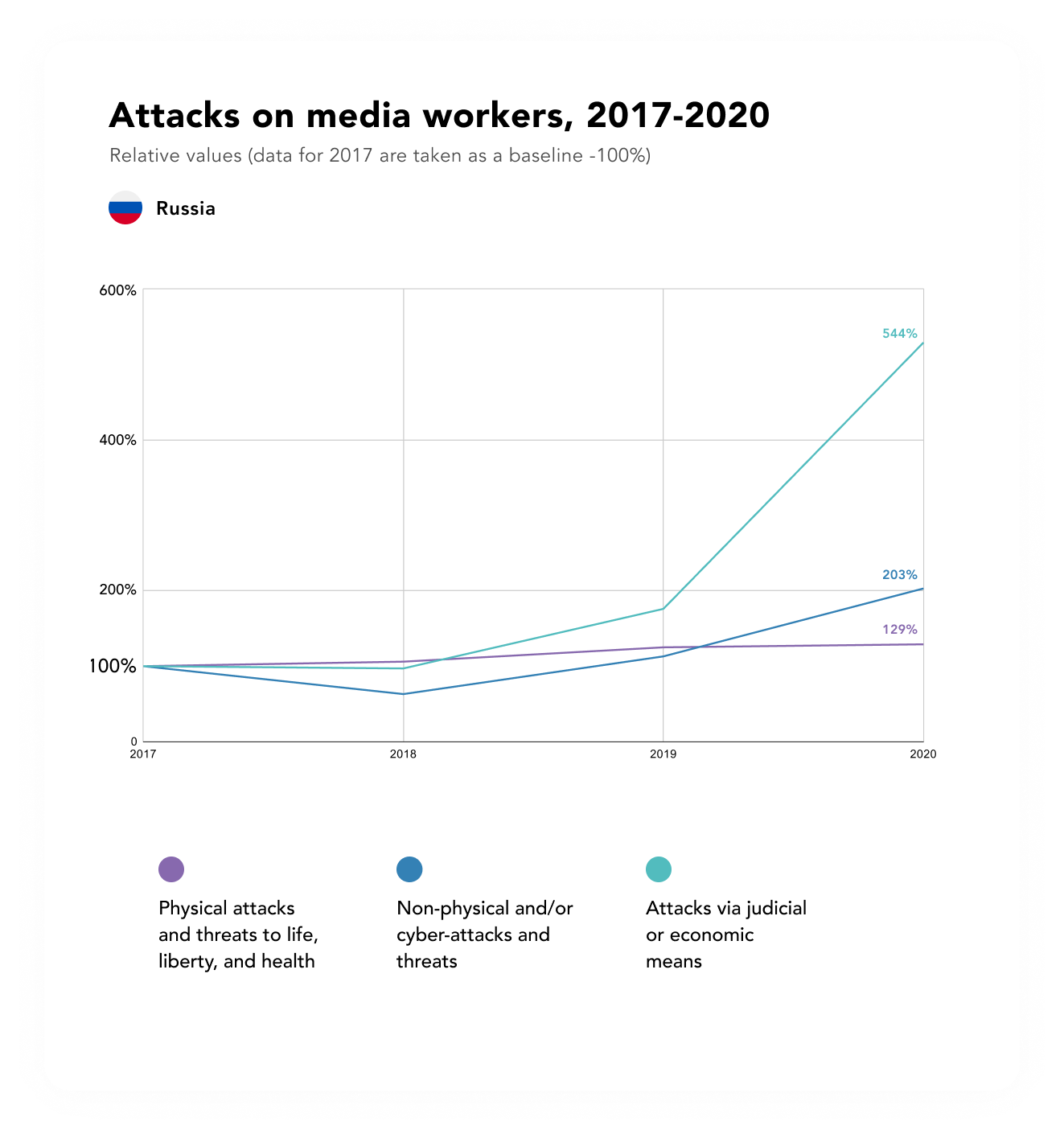

Graph below represents a quantitative analysis of the three main types of attacks in relation to journalists on the territory of Kazakhstan in the period from January 2017 through December 2020.

The number of attacks in all three categories rose from 2017 through 2020. In comparison with 2017, in 2020 the quantity of attacks via judicial and/or economic means increased by 34%; there were 6% more non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats, and 26% more physical attacks and/or threats to life, liberty, and health.

The main objective of the threats is to impede the publication of materials and to suppress civic activism. Threats of physical violence remained unpunished in practice: cases with respect to the not large number of claims lodged by representatives of the media were either quietly dropped or closed “due to the absence of the event of a crime” in nearly one hundred percent of the cases.

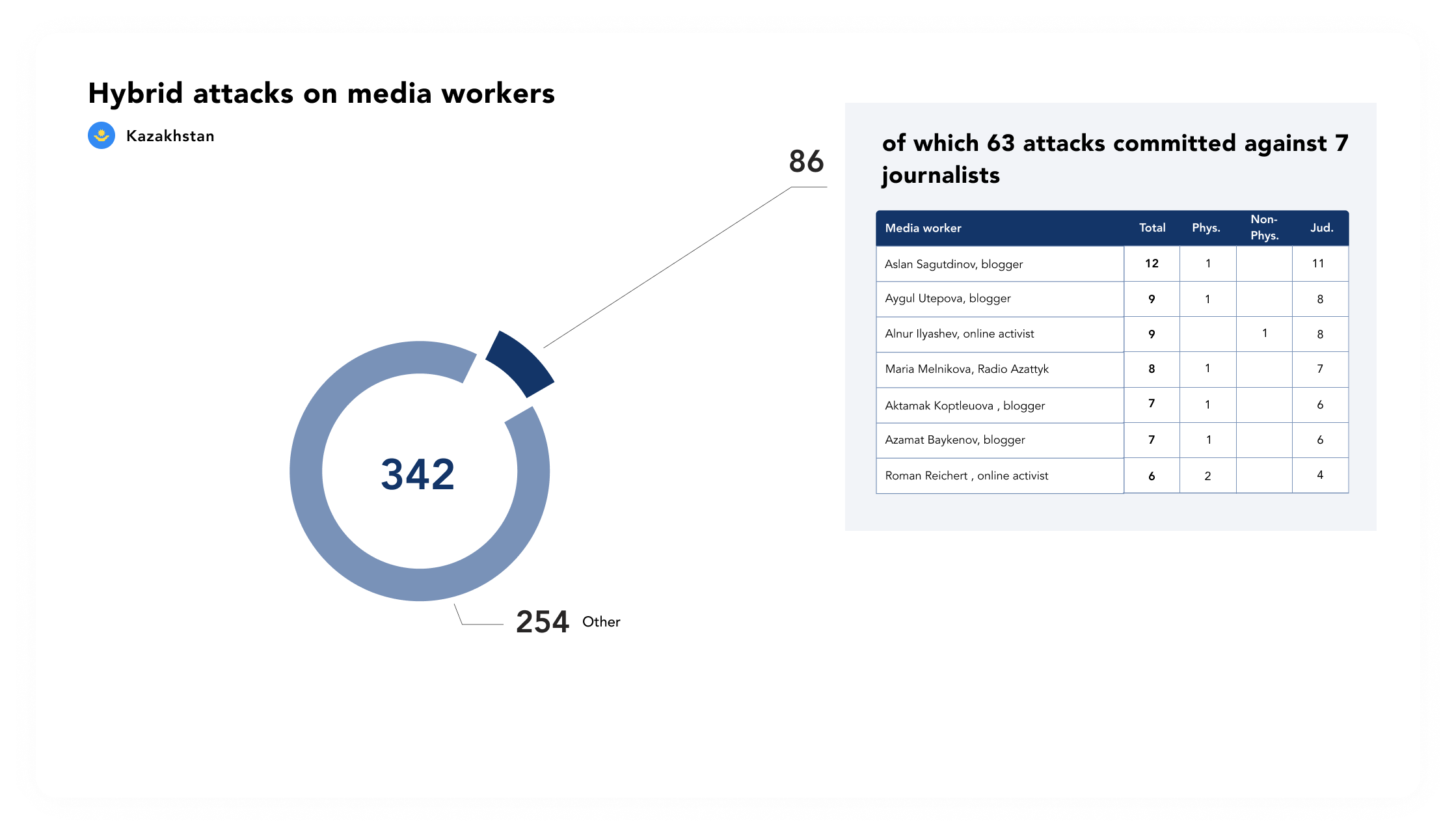

For the purposes of more precisely reflecting combination assaults on media workers in 2020 we are introducing a new category of attacks – hybrid.

We are calling systematic persecution of some publication or media worker with the use of tools from two or more categories of assaults – physical, non-physical, and judicial/economic – “hybrid”. Such a combination of means involving and not involving force with judicial means of pressure on undesirable journalists is carried out with a view to demoralising them or getting them to self-censor or to give up the profession or even life itself.

In 2020, 86 hybrid attacks were recorded, of which 63 attacks committed against 7 journalists. Presented below is the list of the journalists and bloggers who were being subjected to the most intensive hybrid attacks in 2020.

4/ PRESSURE ON JOURNALISTS UNDER THE PRETEXT OF RESTRICTIONS CONNECTED WITH THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

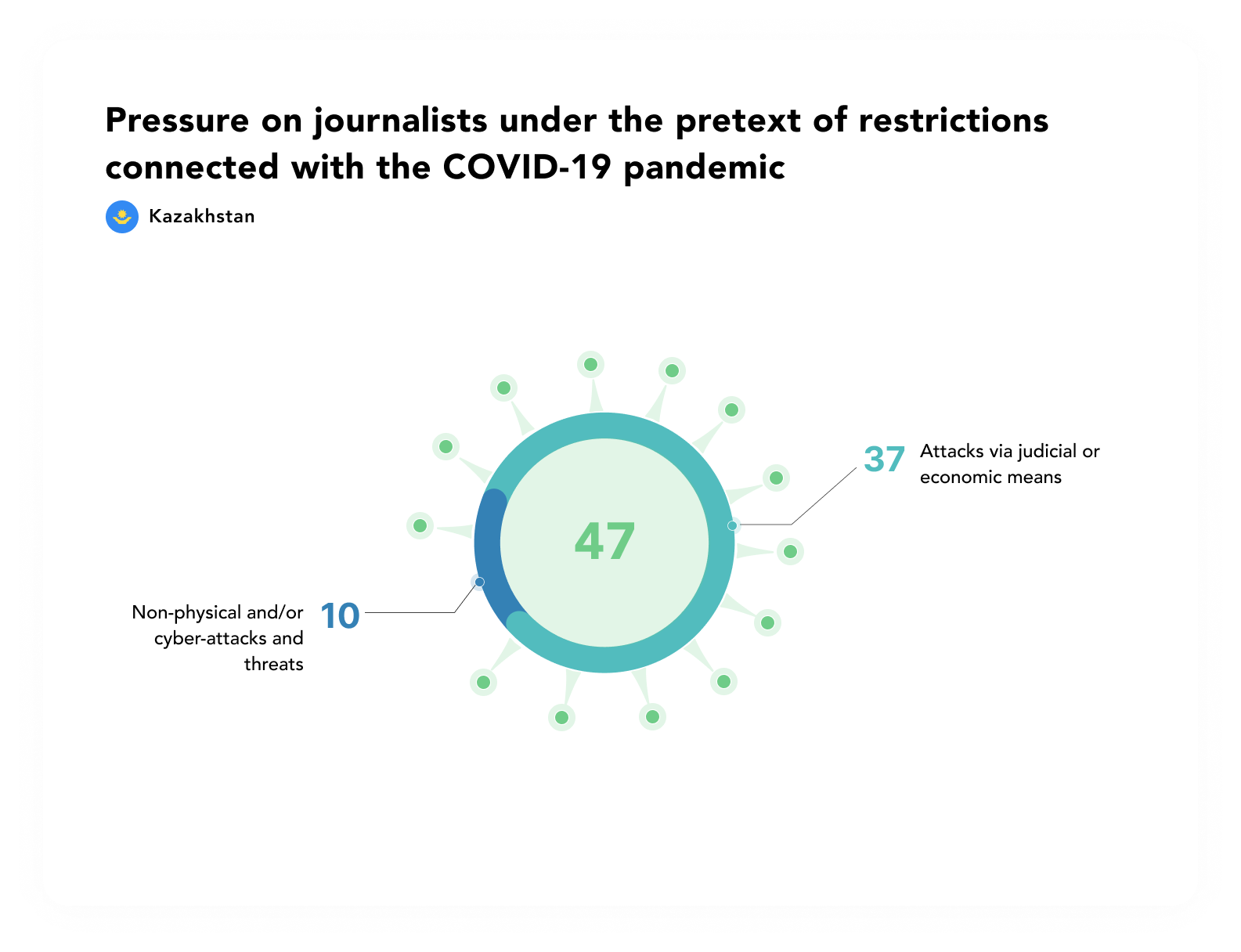

A state of emergency was introduced in Kazakhstan in connection with the spread of COVID-19, and quarantine restrictions remained in effect after it had been lifted. In this context, attacks were undertaken in relation to journalists, bloggers, and online activists via judicial and/or economic means (37 instances), as well as non-physical attacks and threats (10 instances). The main source of the threats (43 instances) are representatives of the authorities.

The graph represents the sub-categories of attacks/restrictions within the framework of the quarantine measures. Remaining in the top three methods of pressure on media workers, bloggers, and online activists are court trials (12) on charges of dissemination of knowingly false information in the period of a state of emergency and violation of the state of emergency regime, illegal impediments to journalistic activity (9), and administrative arrests and remand (7).

- On 28 March, blogger and civic activist Dias Moldalimov [Moldaälımov] was detained and delivered to the Almaty Police Department in connection with a pre-trial investigation into dissemination of knowingly false information in the conditions of a state of emergency (article 274 of the Criminal Code of the RK). The investigator proposed that Moldalimov give confessionary testimony; Moldalimov, however, exercised his constitutional right and refused. The reason for the prosecution became a video address on a YouTube channel from 27 March, in which Moldalimov had severely criticised the actions of the authorities during the time of the quarantine.

- On 18 April, civic activist Alnur [Älnūr] Ilyashev was arrested for two months on suspicion of “dissemination of knowingly false information during the time of a state of emergency”. On 22 June, the online activist was sentenced to three years of restriction of liberty, 100 hours of community service, and a five-year prohibition on public activity. His posts on Facebook criticising the ruling party, Nur Otan, formed the basis of the charges. Ilyashev declared that the verdict was a way of silencing him.

- On 18 April, a well-known public figure, former head of the KTK television channel Arman Shurayev [Şoraev], was detained in Karaganda [Qarağandı] on suspicion of dissemination of knowingly false information in the conditions of a state of emergency. Shurayev was placed in a temporary holding pre-trial detention facility. On 20 April, with the sanction of the court, he was released against a signed pledge not to leave the city.

- On 24 April, a production team from the KTK television channel – correspondent Beken Alirakhimov [Älirahymov] and television camera operator Manas Sharipov [Şärıpov] – was detained on the territory of the regional hospital in Atyrau at the time of shooting a story about the transfer of 257 medical personnel who had been in contact with infected people to a specialised early treatment tuberculosis clinic in Mahambet District. The journalists were charged with violation of the state of emergency regime. An administrative court issued them a penalty in the form of a warning.

5/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

24 physical attacks and threats to the life, liberty, and health of media workers were recorded in 2020. Of these, 20 were non-fatal attacks, beatings, and injuries, in 13 of which the journalists suffered as the result of the actions of police and security service employees.

- On 10 January, security at the KazMedia Ortalygy [Ortalığı] television centre grabbed Vlast.kz journalist Tamara Vaal and began twisting her arms as she was trying to record Kazakhstan vice-premier Roman Sklyar’s commentary after a briefing.

- On 22 February, civic activist and blogger Aslan Sagutdinov was detained next to the place of an alleged unsanctioned rally in Uralsk. During the arrest,they tore his jacket; one of the policemen split his lip with a blow to the head. After Sagutdinov started feeling unwell in the police station (as the result of the ensuing aneurysm), they drove him in an ambulance to a hospital.

- On 17 March, head of the 101tv.kz public internet television Botagoz [Botaköz] Omarova was beaten,by a security employee working for a construction company, to which she had come with an editorial query.

- On 25 September, Radio Azattyq journalist Khadisha Akayeva [Aqayeva], covering detentions in Semey, reported that she had been subjected to a brutish detaining by police. “When they were dragging me into the police van, they injured my finger, broke my nails, and tore out some of my hair”, recounted Akayeva.

- On 24 October, Radio Azattyq reporter Sаniya Toyken was subjected to an assault by a policeman while covering an event in support of political prisoners.

The only fatal incident took place on 24 February 2020: the online activist Dulat Agadil [Ağadıl] died in a pre-trial detention facility in Nur-Sultan several hours after being taken into custody. According to the official story, death came due to acute cardiac insufficiency. Many activists and human rights advocates do not believe this story. They consider that the civic activist had been subjected to torture in the pre-trial detention facility, after which he passed away.

Two instances of the use of punitive medicine are known about:

- On 12 November, a court decreed to place blogger and journalist Aygul Utepova [Aigül Ötepova] in a specialised early treatment psychiatric clinic for involuntary observation. The author of critical posts had been detained on suspicion of participation in the banned DCK movement and placed under house arrest on 17 September 2020.

- On 16 April, online activist Asanali Suyunbayev [Asanälı Süieubaev] was detained, and after that placed in a psychiatric hospital. The hospitalisation was implemented with the participation of the police officers who had stopped Suyunbayev on the street.

One instance of pressure on a media worker by means of physical pressure on relatives and loved ones was recorded:

- On 31 March, a criminal case of “organisation and participation in the activity of a civic or religious association or other organisation after a decision of a court on the banning of their activity or liquidation in connection with the implementation by them of extremism or terrorism” (article 405 of the Criminal Code of the RK) was initiated in relation to civic activist Roman Reichert. On 31 March, policemen conducted a search in his house. They used violent force on Reichert and his wife when the activist tried to get dressed. His wife Regina Belalova tried to film what was happening, but they snatched the smartphone from her.

6/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

The most popular methods of pressure on media workers, bloggers, and online activists are: illegal impediments to journalistic activity, denial of access to information (25); bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber- (11); and damage to/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials, print run (5).

It ought to be noted that in 19 of the 25 instances, representatives of the media encountered impediments to journalistic activity on the part of representatives of the authorities. The impediments were expressed in refusing admittance or denying an online connection for media representatives to sessions of state bodies and courts, creation of obstacles to coverage of various events, and prohibitions on commenting on high-profile court trials.

- On 6 June, when Radio Azattyq reporter Dilara Isa was conducting a video shoot of rally participants being detained in Shymkent [Şymkent], two unknown persons tried to prevent the detainings from getting into the shot by blocking the camera with umbrellas. One of them introduced himself as an employee of the internal policy administration of the Shymkent akimat. Besides that, a man working in the press service of the city police department was continuously shooting video of the reporter as she was working.

- On 3 August, news resource iagorod.kz journalist Irina Starikova was not allowed into a meeting between entrepreneurs and the deputy akim [mayor] of the city of Rudny. “An employee of the Rudny akimat‘s internal policy section reported that the upcoming meeting was ‘closed’ and admission is not allowed,” writes Starikova. After that an employee of the security service tried to prohibit the journalist from shooting video and photos on a smartphone camera.

The second widespread method of attacks on journalists was bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber- (11 instances):

- On 2 March, MIA «KazTAG» correspondent Mahambet Abzhan [Äbjan], who had earlier been released early on parole, received a notification on WhatsApp from the precinct police inspector. The policeman reported that the journalist must come to division No. 28 of Saryarka District of Nur-Sultan and stay in a temporary holding cell until morning, because a session related to his case was scheduled to take place in the administrative court in the morning. As the precinct inspector said, “now there is such a way of doing things, that everybody’s trial goes like this”. After Abzhan wrote about this on Facebook, the question of spending the night in the police division was taken off the table.

- On 17 June, it became known that pressure is being exerted on civic activist Alnur [Älnūr] Ilyashev in a pre-trial detention facility. “They’re planting provocateurs and people who threaten me in the cell! It has likewise become known to us that Alnur’s state of health has deteriorated sharply and they’re not providing him with the proper medical care! His chronic illness, asthma, has become acute! The system is trying to break him or physically destroy him!”, reports the prisoner’s close associate Marat Tūrymbetov.

- On 12 September, journalist Tauirbek Bozekenov [Täuırbek Bözekenov] declared that he was being threatened with judicial prosecutions because of publications on Facebook. The journalist writes about the environmental situation in the region of Atyrau. The threats came after Bozekenov’s refusal to remove the publications.

- On 2 December, a well-known blogger from Shymkent, Kirill Pavlov, reported about a threat of reprisal and the police’s refusal to take his statement reporting the crime: “There is a threat to my life. A person who had previously openly expressed dislike for my ethnicity writes that he will come to Shymkent, deal with me, cut me, stab me. I had to go to the police, but the report of the crime was not accepted, they asked me to wait for someone. Just in case, I will post this video so that you know that if something happens to my family or me, blame Shyngys Sadenov [Şyŋğys Sädenov] for it”, said Pavlov in a video on Facebook.

7/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

In 2020, the top five main methods of pressure on media workers included: court trials (59), charges of libel and reputational damage (53), summonses for interrogation and questioning (28), short-term detention (22), and administrative arrests, remand, and pre-trial detention (16). The majority of short-term detentions of journalists took place during coverage of protests.

Court trials are the most widespread method of pressure on journalists, bloggers, and online activists in Kazakhstan. In the majority of situations, criminal cases on charges of dissemination of false information, inciting hate, and participation in the activity of an extremist organisation, as well as administrative cases for violating the state of emergency regime, end with guilty verdicts. Short-term detentions and arrests precede the charges in such cases.

- On 16 May, the Petropavlovsk city court sentenced blogger Azamat Baykenov to one year of restriction of liberty, suspended, on a charge of “participation in the activity of a banned organisation”. Besides that, the court obligated Baykenov to pay 10 monthly calculation indices (around 27 thousand tenge, or on the order of 65 dollars) into the Victims’ Compensation Fund. The blogger was prohibited from using social media over for three years. Baykenov denies the charges.