ARMENIA

An independent expert opinion about Attacks on media workers in Armenia report

In 2020, attacks and threats against journalists in Armenia dramatically increased as compared with the previous years. This was largely due to the unprecedented events that unfolded in the last year such as: restrictions caused by the COVID 19 pandemic, the full-scale war in Nagorno Karabagh, the stressful post-war situation after the heavy toll casualties and military losses, which resulted in political crisis in Armenia.

Journalists experienced physical attacks, arbitrary apprehension and arrest, unprecedented number of defamation lawsuits, blocking and removal of their content from Internet, administrative fines for violation of the COVID-19 related state of emergency and later the Martial law imposed by the government as the war started. During the Martial law, the journalists and the media outlets were bound be overly restrictive rules limiting the spread of critical information that deviated from the official version of the war events. As a punishment, journalists were subjected to disproportional administrative fines that often exceeded those for criminal offences under the penal code. Those fines, often imposed repeatedly against the same media entity, had a chilling effect on the freedom of reporting on controversial war and pandemic related events that the government was not inclined to make public.

The number of incidents of attacks, assaults, threats, bullying, lawsuits and administrative fines increased 3 to 5 times in comparison to previous years. Often the journalists were assaulted, verbally and physically, by protestors at rallies and demonstrations for their perceived affiliation to a given political force. In such instances, the journalists and camera operators were forced to stop the news coverage and leave the public event, hence, being discriminated on the account of their profession. The authorities, in turn, discriminated against certain media outlets by failing to open criminal investigation or take preventive measures against assaults as a redress to the situation.

The rise of civil defamation court cases against media entities with high award demands was another disturbing trend of the year 2020. Along with that, government officials started bringing defamation and insult lawsuits against media entities and individual journalists which had not been practiced before. In addition, the law enforcement bodiesintroduced the summoning of journalists for questioning about the content of their posts on the social networks, such as Facebook. Moreover, the authorities initiated legislative reform that will increase the statutory reward for defamation and insult lawsuits fivefold. This initiative was highly criticised by the civil society and media community.

Ara Ghazaryan

Legal expert

Authors of the report – The Committee to Protect Freedom of Expression (CPFE)

1/ KEY FINDINGS

259 instances of attacks/threats in relation to professional and citizen media workers and editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Armenia in 2020 were identified and analysed in the course of the research. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Armenian, and English languages using the method of content analysis. A list of the main sources is presented in the Annex 10.

- In 2020 the growth in the number of violations of the rights of journalists and media outlets in Armenia was attributable to the introduction of restrictive measures connected with the COVID-19 pandemic, the all-out war in Nagorno-Karabakh, and an exacerbation of the socio-political situation in the post-war period. The number of attacks in 2020 in comparison with 2019 increased by 34%.

- Physical attacks on journalists were perpetrated for the most part during coverage of mass protests; moreover, facts have been recorded of assaults on media representatives both on the part of participants in the protests and on the part of the police. In comparison with 2019, the number of media workers who have suffered from physical attacks increased two-fold. Armenian and foreign journalists carrying out their professional duties were wounded in the course of the Karabakh war.

- 37 facts of clamping down on the media were registered in the course of the state of emergency introduced in Armenia in connection with the spread of COVID-19.

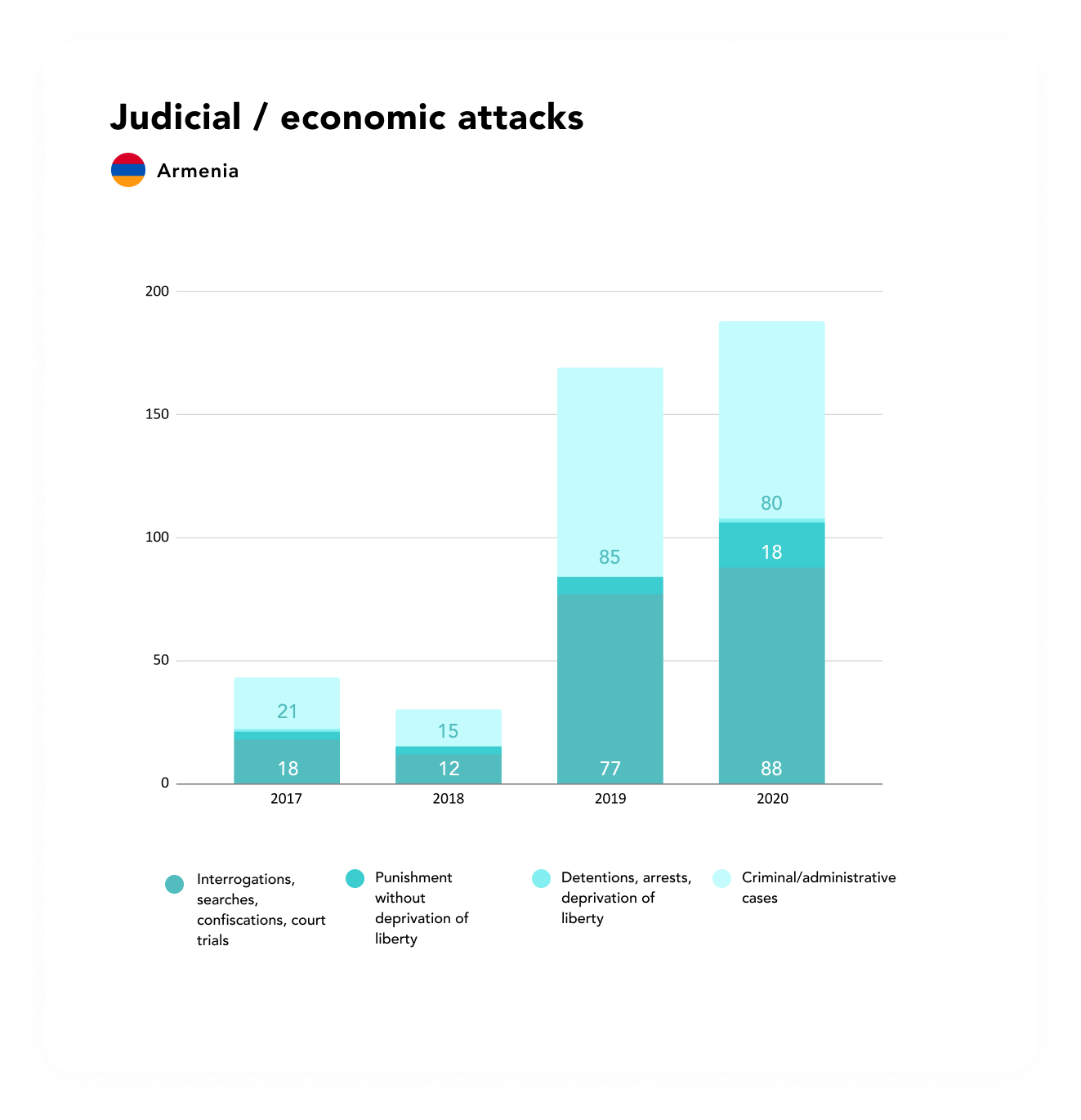

- The tendency to use judicial mechanisms to exert pressure on journalists and media outlets, characteristic of previous years, continued in 2020. Courts agreed to hear 88 lawsuits against them over the year. The overwhelming majority of these court cases (79) were connected with accusations of insult and libel.

- In comparison with the previous year, the number of non-physical attacks in relation to media workers increased more than two-fold in 2020.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MASS MEDIA IN ARMENIA

In Reporters Without Borders’ annual rating for 2020 Armenia took 61st place, as it had in 2019. According to the Freedom on the Net report for 2020 drawn up by Freedom House, the internet in Armenia is free (75 out of 100 points). The authors of the report declare that “internet freedom in Armenia has improved since the Velvet Revolution swept Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan into power in 2018.”

The year 2020 became a period of extremely severe tests for Armenia and the Armenian media. On 16 March the government of the RA introduced a state of emergency in the country to combat the spread of COVID-19. Tight restrictions were introduced on the movement of citizens and a prohibition on public events and gatherings, including marches, demonstrations, and any protests.

4 of the items in the government decree concerned media activity. Journalists were prohibited from disseminating anything other than official information, as well as from publishing materials that could evoke panic among the populace. At the same time, it was not specified what type of publications were being referred to. After journalists’ organisations sharply criticised the items of the decree that concerned the media in a joint declaration, the government of the RA first noticeably relaxed the restrictive measures, and afterwards lifted them altogether.

Nevertheless the state of emergency was being extended month by month, which was becoming a pretext for political speculations. The opposition, including those forces that had been removed from power as a result of the Velvet Revolution, accused Nikol Pashinyan’s government of artificially restraining the protest movement. Gagik Tsarukyan, leader of the second-largest parliamentary faction, Prosperous Armenia, declared that the government as a whole must resign as it had botched the fight against the coronavirus and had brought the country to economic collapse.

The authorities, in turn, asserted that Tsarukyan’s sudden flurry of activity and his desire to organise protests were connected with the fact that a criminal case had been initiated against him on a charge of bribing voters in the period of the parliamentary elections of 2017 and the fact that he had been stripped of his parliamentary immunity.

When the leader of Prosperous Armenia was summoned to the National Security Service to give testimony, his supporters conducted a demonstration outside the NSS building even though, as has already been noted, mass events were prohibited. During the time of the dispersal of the demonstrators, the police used physical force against journalists as well, as a result of which 7 representatives of various media outlets suffered. Several days earlier a policeman had used force under analogous circumstances against a photo correspondent from the Photolure news agency.

The socio-political situation in Armenia became even more acute as the result of the all-out war unleashed by Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh on 27 September. Whilst bloody combat was taking place at the front, the opposition was demanding the prime minister’s resignation. This demand intensified after the leaders of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia signed a tripartite declaration on the cessation of military operations, which in essence became a capitulation for the Armenian side.

From the outset of the armed conflict Pashinyan’s government declared martial law in the country. Besides other harsh measures, restrictions were introduced concerning the media. In particular it was demanded that nothing but official information be published in the coverage of military operations and those connected with them. Materials that criticised or cast doubt on the government’s policy and the military leadership’s decisions were prohibited. Any publications that might evoke panic likewise turned out to be under prohibition, although this wording was not concretised. In the period of martial law the authorities were forcing the mass media, with the help of the police, not only to remove “prohibited materials”, but also to pay a fine in an amount of 700 thousand drams (around 1400 US dollars) for their publication. 13 Armenian media outlets encountered such problems.

Martial law was extended even after the cessation of military operations. This was primarily attributable to the mass disorders that took place in Yerevan on the night of 9-10 November: when it became known about the content of the tripartite agreement, enraged mobs forced their way into the parliament and government buildings and began to smash everything they could lay their hands on. The chairman of the National Assembly, Ararat Mirzoyan, was beaten unconscious. Searching for prime minister Nikol Pashinyan, the mob found its way into his residence but he turned out not to be there.

These and subsequent protests numbering many thousands of participants were led by an opposition coalition of 17 parties that had formed, the core of which consisted of the political forces that had been removed from power as the result of the Velvet Revolution of 2018. Their main demand was the immediate resignation of Pashinyan, the appointment of a candidate from the united opposition to the post of prime minister, and the formation of a transition government that would lead the country out of the crisis and organise extraordinary parliamentary elections.

Although the actions of protest by the united opposition did not find sufficient mass support, the socio-political situation in Armenia remained extremely tense. In these conditions the activity of the media was exceedingly complicated. Their polarisation intensified, and the overwhelming majority of the media primarily serve the interests of political sponsors, ever more frequently ignoring their public mission. The increase in attacks on journalists and media outlets, including the flood of legal claims against them, is driven by these realities.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

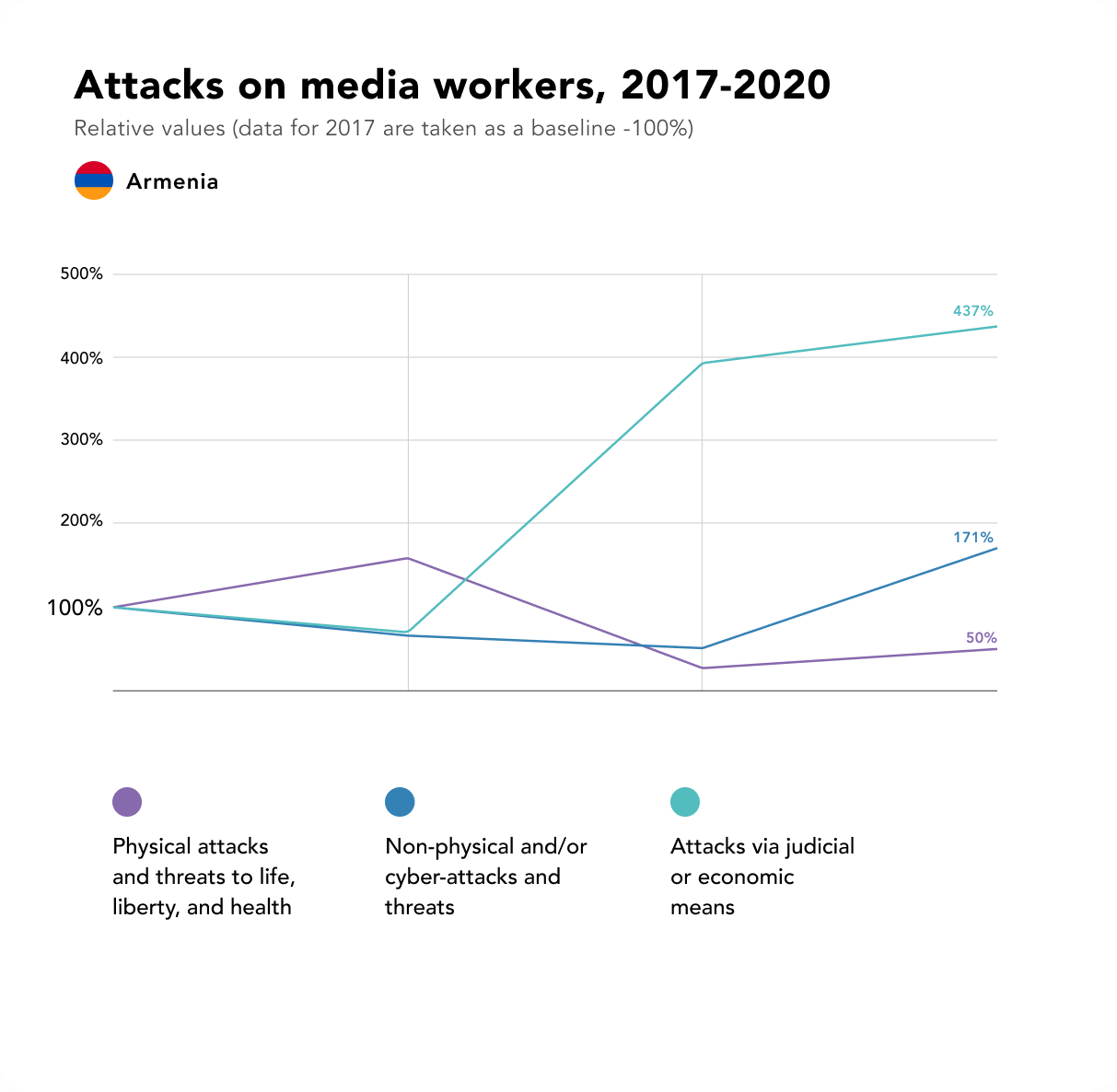

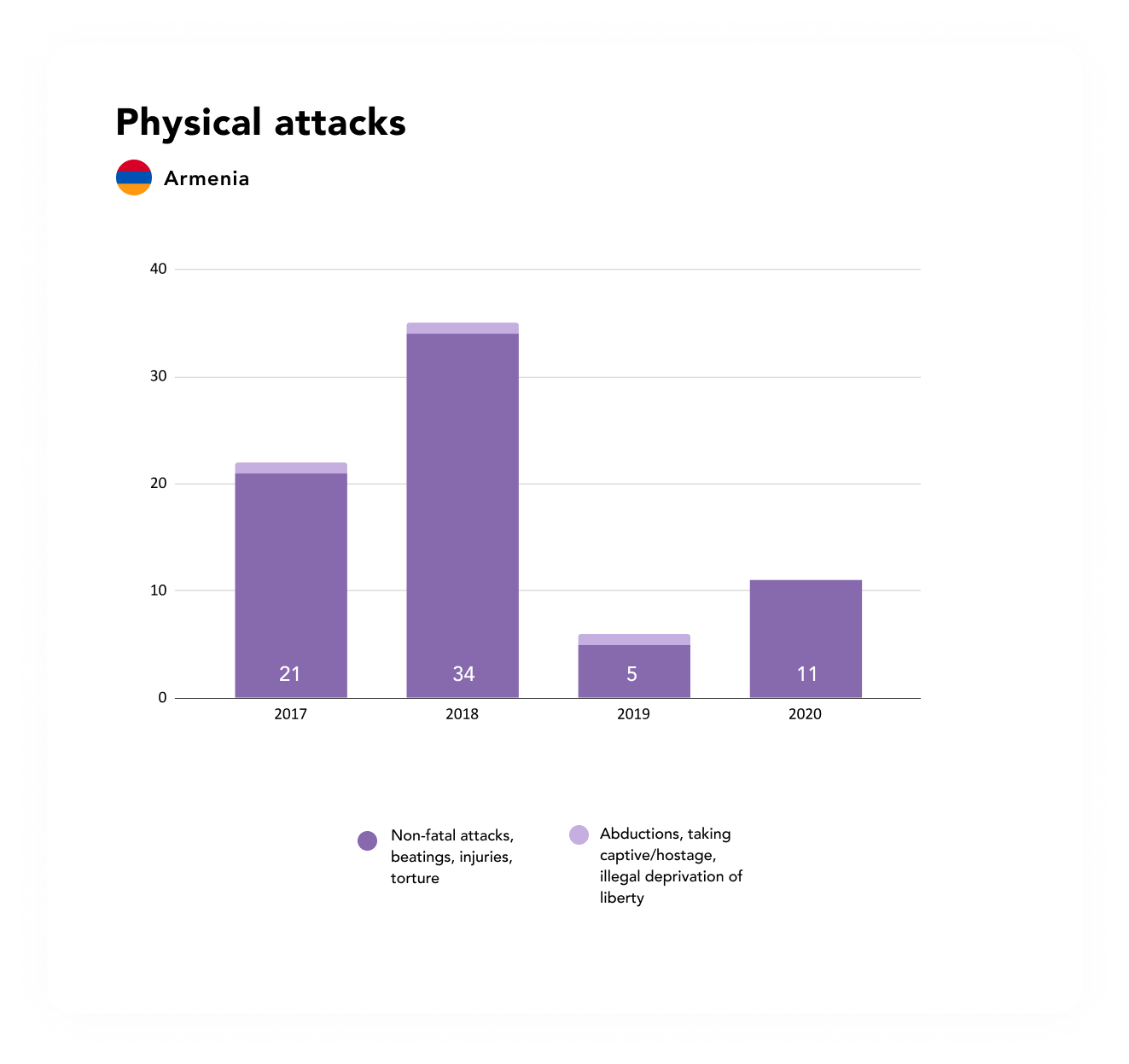

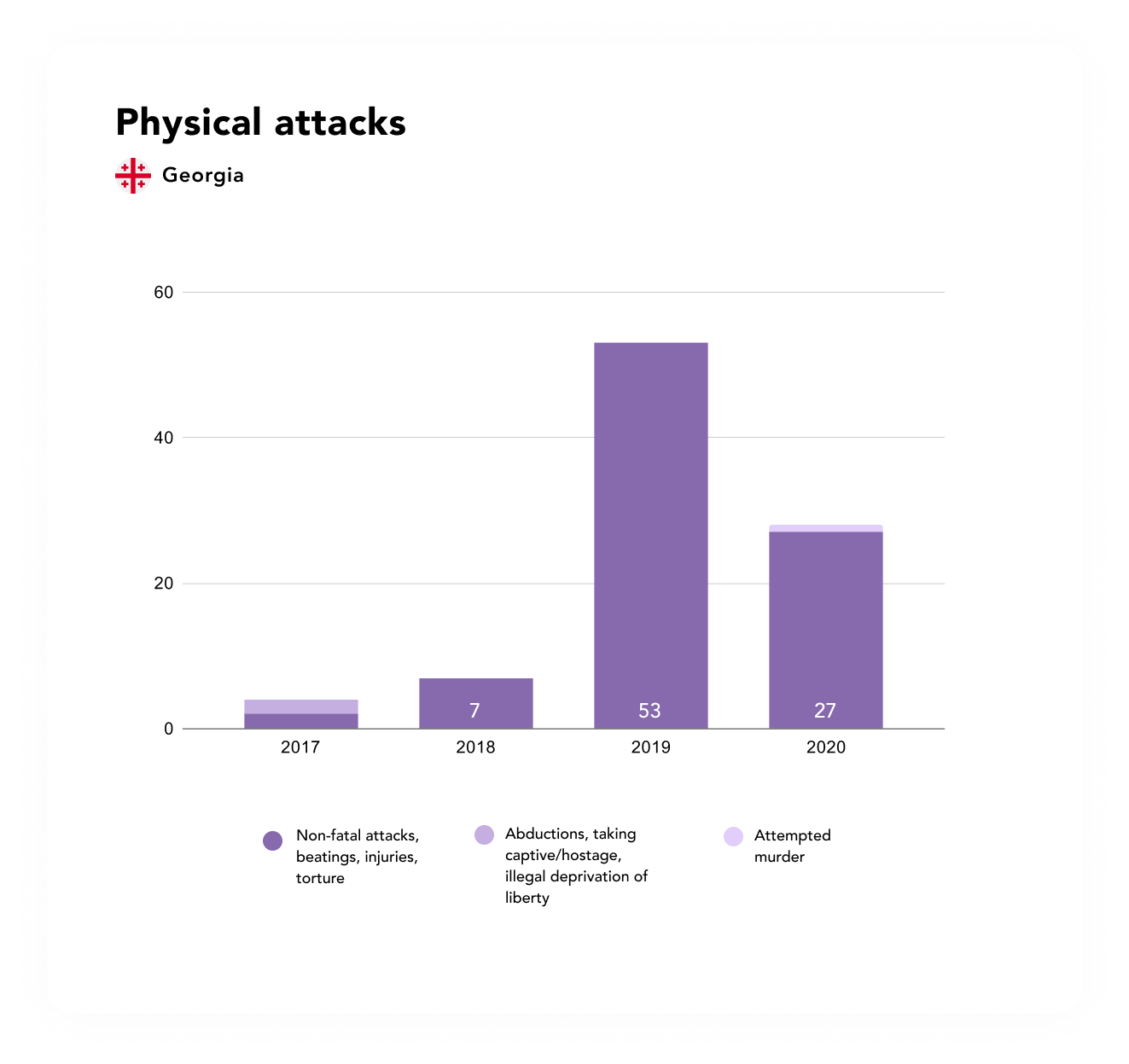

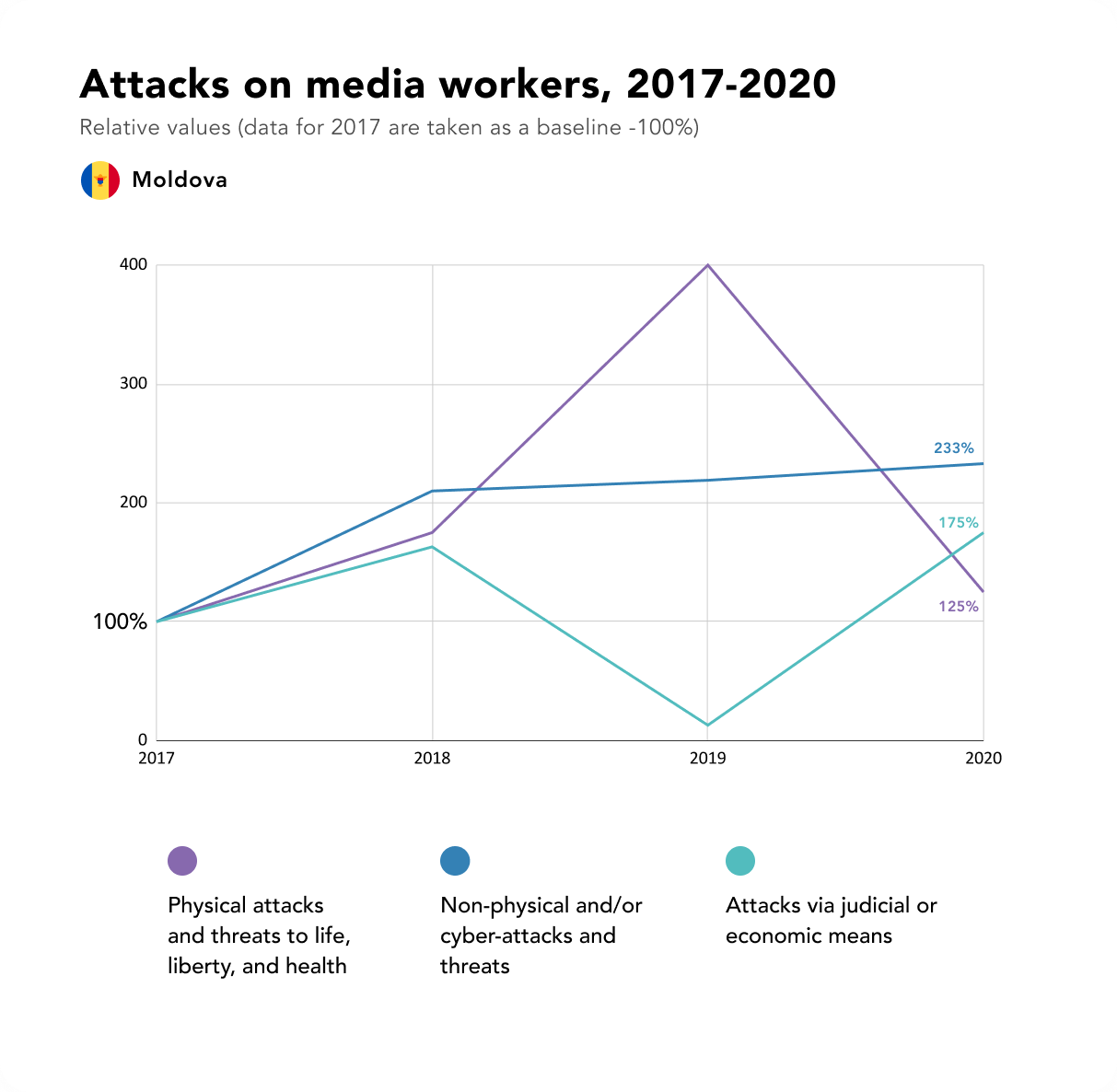

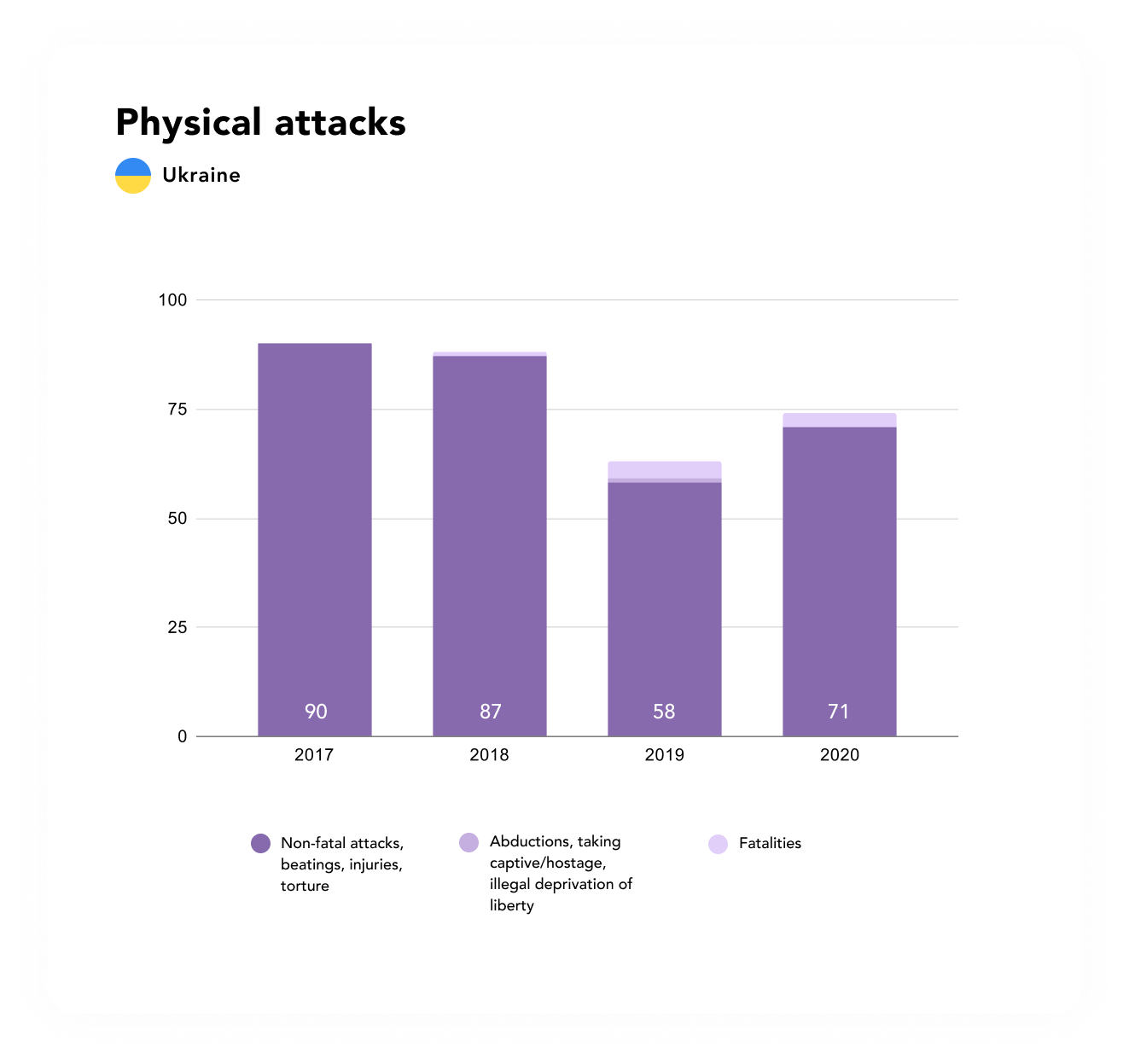

Of all the years of observation of the state of freedom of speech in Armenia and violations of the rights of journalists and media outlets, 2020 became the most unfavourable one for activity in the news sphere. Presented in Figure 1 are data that bear witness to a rise in attacks on journalists in all three categories. In comparison with 2019 the quantity of attacks in 2020 increased by 34%. Although the number of physical assaults on journalists and camera operators is significantly lower than the indicators for 2018 and 2017, a two-fold increase can be observed in this category in comparison with 2019.

In 2020 the quantity of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks was 3.5 times higher than in 2019. The number of attacks via judicial and/or economic means too turned out to be unprecedented: it exceeded the 2017 indicator by 4.5 times and the 2018 one by 6 times. 47% of the attacks of the given category consist of legal claims against journalists and media outlets. 78 of the 88 new cases that courts agreed to hear are connected with charges of libel, insult or reputational damage.

In total there were 259 incidents recorded in 2020. Of the overall number of attacks 84 came from the authorities, 148 from non-representatives of the authorities, and 27 from unknown perpetrators.

The main factors that fuelled the growth in the number of violations of the rights of journalists and media outlets became:

- the restrictions introduced by Armenia’s authorities in the period of the state of emergency associated with the COVID-19 pandemic;

- the harsh demands during the martial law that was introduced from the first day of the all-out military operations in Nagorno-Karabakh;

- the acute socio-political crisis that broke out after the military defeat, and an intolerant attitude towards media employees, especially during their coverage of mass protests.

4/ PRESSURE ON JOURNALISTS UNDER THE PRETEXT OF RESTRICTIONS CONNECTED WITH THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

As has already been noted, the government of the RA adopted a decree on introducing a state of emergency in the country on 16 March 2020 in connection with the spread of COVID-19. 4 of the items in the document directly concerned media activity and prescribed tight restrictions on the coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, disseminating anything other than official information was prohibited, as was publishing materials that could evoke panic among the populace. The government entrusted control over the implementation of the decree to the police.

Although the demands being made had been worded with insufficient clarity and precision and left broad scope for subjective interpretation, the media community was actively protesting against the restrictions that had been introduced. Against a background of sharp criticism, representatives of the government of the RA organised a meeting on 21 March with the heads of the country’s journalistic organisations in order to discuss the immediate situation. On 25 March the restrictions relating to the media were relaxed, and on 13 April they were lifted altogether.

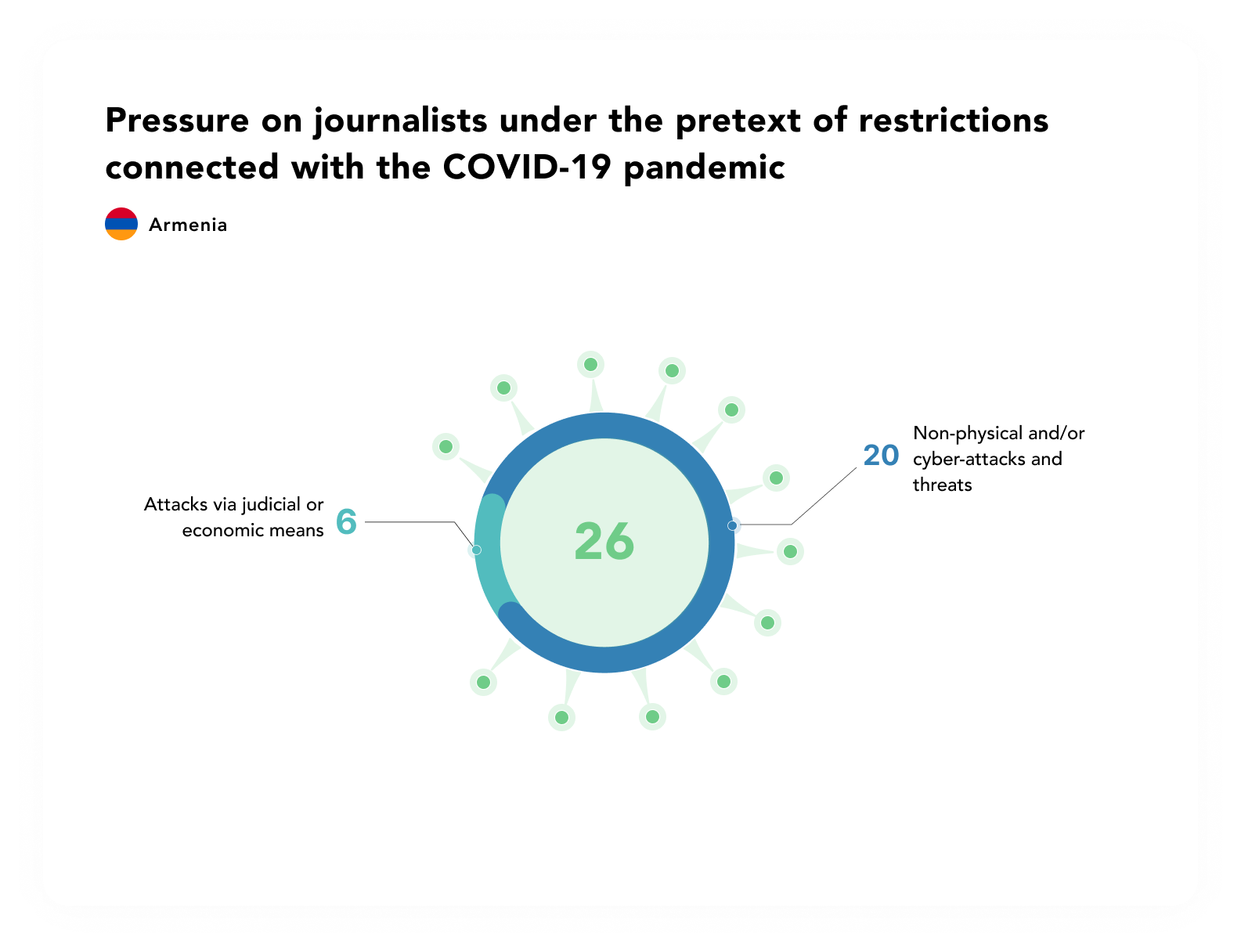

26 instances of pressure on the media were nevertheless recorded during the period that the four mentioned items of the government decree were in effect. In all of these instances, the attacks were coming from representatives of the authorities. Of the incidents recorded, 20 belong to non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats and 6 to attacks via judicial and/or economic means. Recorded over the period under review were 20 instances of bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of force and violence including cyber-, 5 incidents in the “shutting down a media outlet/blocking an internet site/request to remove or block articles, seizure of an entire print run” category, and one incident in the “administrative offence/fine” category.

- On 20 March the police commandant’s office demanded of the Pastinfo.am news website that it delete material under the headline “An elderly female inhabitant of Echmiadzin has been diagnosed with pneumonia, she has a fever, however she has not passed a test and is not hospitalised”. The editorial office carried out the demand, but immediately published the warning letter and paraphrased the content of the deleted publication.

- On 20 March editor-in-chief of the 167.am website Satik Seyranyan declared that she had been telephoned by the 6th administration of the police of the RA, who demanded that she delete from their website a publication of a video recording on Facebook by former prime minister of the RA Grant Bagratyan in which accusations addressed at the authorities with respect to the spread of COVID-19 were contained. The same kind of warning letter was sent to the Armday.am, Hayeli.am, and Yerkir.am websites.

- On 26 March editor-in-chief of the Politik.am website Boris Murazi reported live on his Facebook page that the editorial office had posted an item about a resident of the city of Gyumri who had died, presumably of COVID-19; however, it had not proven possible to get clarifications in this regard from the police commandant’s office responsible for compliance with the state of emergency. In Boris Murazi’s words, the commandant’s office press secretary, Mane Gevorkyan, refused to answer questions, citing busyness, while on account of the live transmission the editor-in-chief faced the threat of policemen being despatched to the editorial office and of being fined.

- On 31 March the police sent a warning letter to the editorial office of the Lurer.com news website with a demanding that they delete one of the publications about COVID-19, as it violated the government decree of 16 March. Similar warning letters were sent to the editorial offices of the Zham.am, Hraparak.am, and News.am websites, which had reposted this publication.

- On 13 April editor of the Pastinfo.am news website Sona Truzyan reported on Facebook that the police had initiated administrative proceedings in relation to the editorial office for reposting information from another media outlet about someone ill with COVID-19. The Pastinfo.am editorial office was ultimately not fined.

- On 3 July policemen visited the Armnews and Channel 5 television companies with the aim of initiating administrative proceedings in connection with the fact that employees of these television companies were not wearing masks during television air time.

It is worth noting that having received warning letters from the police about the necessity of deleting the material, in 11 instances the media outlets did not fulfil this demand. However, in contrast with the period of martial law, when a fine in an amount of 700 thousand drams (around 1400 US dollars) was imposed for any “prohibited” publication, in the course of the state of emergency brought about by the pandemic the authorities refrained from applying financial measures of liability in relation to the media.

5/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

The overall number of physical attacks on media workers from 2017 through the year 2020 is presented below. In 2020 all recorded incidents took the form of non-fatal attacks/beatings/injury/torture. In 7 of the 11 instances, the attacks came from representatives of the authorities.

The greatest number of physical attacks were recorded during the mass protests brought about by the exacerbation of the socio-political situation in the country. Whilst covering rallies, demonstrations, and marches media employees were subjected to assaults not only on the part of policemen (7), but on the part of participants in these events as well (1):

- On 14 June police impeded the professional activity of Photolure news agency photo reporter Lusi Sargsyan during a protest held by supporters of Prosperous Armenia party leader Garik Tsarukyan. She reported that a policeman grabbed her by the arm and threw her onto the sidewalk.

- On 16 July, when the police were pushing supporters of Prosperous Armenia party leader Gagik Jhangiryan away from the National Security Service building where the politician’s interrogation was taking place, journalists covering the protest suffered from the actions of the police. Some of them received bodily injuries. In particular News.am correspondent Liana Sargsyan, Tert.am journalist Ani Gevorkyan, Yerkir.am correspondent Tatevik Kostandyan, Kentron television journalist Artur Hakopyan, and MegaNews.am website editor Margarita Davtyan suffered.

- On 1 December policemen twisted Erkin-media television company video camera operator Hayk Sukiasyan‘s arms and seated him in a car during a dispersal of demonstrators demanding the resignation of prime minister Nikol Pashinyan. After some time had passed they released him. During the incident they broke his video camera.

- On 19 December Radio Liberty camera operator Davit Harutyunyan was subjected to physical violence in Yerevan’s Yerablur military pantheon, where a commemoration ceremony for those who had perished in the Karabakh war was taking place. Opposition supporters had organised a picket in order to not let the participants in the funeral procession with prime minister Nikol Pashinyan at the head into the cemetery. Having noticed the radio station’s camera operator filming the ceremony, the picketers assaulted Harutyunyan with cries of “Here’s ‘Liberty’!”, knocked him to the ground, and inflicted a multitude of blows. Procession participants from among Pashinyan’s supporters managed to protect the journalist and move him away to safety.

Besides physical attacks associated with protests, the following incidents were recorded.

- On 10 November at approximately 4 o’clock in the morning, around forty men tried to storm the Radio Liberty office. They were kicking and banging on the doors, as well as shouting insults at the employees. In the words of executive producer Artak Hambardzumyan, when he started filming what was taking place on a telephone, an unknown person punched him, while another hit and pushed cameraman Sevak Mesropyan. “We came to take away the servers, so you wouldn’t go on the air. You are traitors, you’re Turks, you’re not going to get on the air”, the assailants were saying. The group abandoned the office when the radio station employees called the police.

- On 16 November editor-in-chief of the BlogNews.am news portal Konstantin Ter-Nakalyan was assaulted. According to media reports, several people on the street got into an argument with Ter-Nakalyan regarding the war in Nagorno-Karabakh, and when a fight broke out one of the assailants inflicted knife wounds to his ear and face. Despite the fact that Ter-Nakalyan refused to submit a report of crime to the police and to give testimony, one of the suspects was detained.

6/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

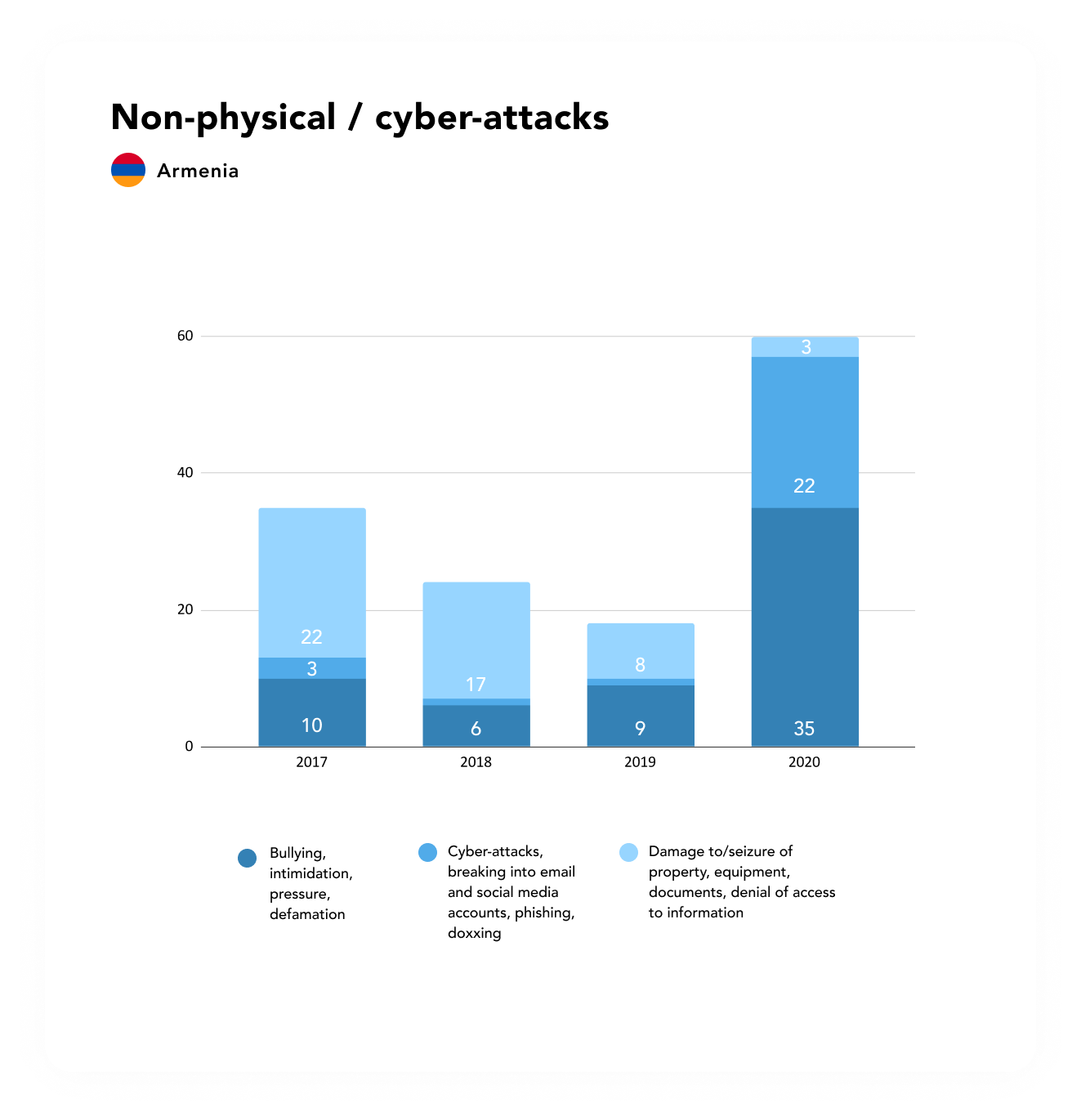

61 incidents were recorded over the period under consideration, which is significantly more than in 2017-2019. The main methods of pressure in the given category became bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber- (33) and cyber-, DDoS, and hacker attack on a media outlet (22).

2020 turned out to be an unprecedented year for Armenia in terms of the number of cyber-attacks: 22 cyber-, DDoS, and hacker attacks on media outlets were recorded. In the main this stemmed from the information war in the period of all-out military operations in Nagorno-Karabakh, when Azerbaijani and Turkish hackers were arranging mass attacks on Armenian websites.

- On 12 July the internet publication Hetq.am was subjected to a hacker attack. The website was restored the next day. In the words of specialists, the attack had been undertaken from abroad.

- On 14 July the News.am, Tert.am, Armtimes.com, A1plus.am, and Aysor.am news portals were subjected to a hacker attack. Experts connect this with the Armenian-Azerbaijani military clashes in the border zone of Tavush Province. In particular DDoS attacks on the Tert.am website were undertaken from Azerbaijan’s side by means of nearly 10 thousand IPs.

- On 27 September Azerbaijani hackers subjected the leading Armenian news websites to DDoS attacks: a1plus.am, armenpress.am, armtimes.com, blognews.am, hetq.am, mamul.am, mediamax.am, and zhamanak.com. Operation of these websites was restored several hours later. The 1in.am and news.am news websites were likewise broken into. Azerbaijani hackers were trying to disseminate their own information by means of these resources. Operation of the websites was restored several hours later.

Bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber-, were the predominant method of pressure on journalists. It is noteworthy that 27 of the 33 attacks in the given category came from representatives of the authorities.

- On 15 February the Court Acts Execution Enforcement Service contacted the editorial office of the Aravot.am news website and demanded a retraction of material representing an abridged version of an article from the Haykakan zhamanak newspaper, despite the fact that the website, remaining true to the code of journalistic ethics, had not reproduced that part of the article which had contained offensive expressions. Aravot.am refused to carry out the agency’s demand.

- On 24 June the Main Administration for Criminal Investigation of the RA police called the editorial office of the Raparak newspaper and said that they had received a letter from a prosecutor in which he gave directions “to study the facts set forth in the article ‘Small circulation and we’ under the byline of Edik Andreasyan, and to resolve the question of holding the author criminally liable”.

- On 1 July the founder of the internet publication Ankakh.com, Vardui Ishkhanyan, was invited to the Main Administration for Criminal Investigation of the RA police to give explanations in connection with posts on Facebook about the former military prosecutor and deputy general prosecutor of the RA, Gagik Jhangiryan. In these publications, Ishkhanyan had called Jahangirian “the father of falsifications” and had written that he is suspected of having committed murders in the army. Ishkhanyan refused to appear at the police station.

- On 19 December on Yerevan’s Republic Square, before the start of a procession of lamentation dedicated to the memory of those who had perished in the Karabakh war, deputy [MP] from the My Step parliamentary faction Andranik Kocharyan subjected journalist Lara Arakelyan from the Channel 5 television company to discrimination. Having refused to answer her questions, the deputy openly declared that he was prepared to talk with any of the mass media correspondents found on the square but not with a representative of Channel 5, whose activity he considers unacceptable. Before and after this dialogue, some participants in the procession, having noticed the television company’s logo, were being rude to the journalist and demanding that she leave and not cover the event.

Journalists were frequently subjected to bullying and pressure on the part of participants in protest rallies, who were actively impeding their work.

- On 5 December in Yerevan at a rally and march of opposition forces the demonstrators displayed intolerance in relation to Radio Liberty correspondent Sarkis Harutyunyan. They were shouting obscenities addressed at him and were demanding that he vacate the place of the event.

- On that same day, 5 December, participants in a rally of opposition forces were impeding the work of Rafael Karamyan, a camera operator for the 1in.am news website. Having noticed the 1in.am logo on the video camera, a group of rally participants came up to the journalist and demanded that he cease filming. This was accompanied by unprintable expletives and threats addressed at the cameraman and his media outlet. Karamyan was forced to turn off the camera and leave.

- On 21 December in Goris Radio Liberty correspondent Robert Zargaryan, covering the visit of prime minister Nikol Pashinyan, was subjected to an attack. Demonstrators were verbally attacking the journalist, impeding his work, and demanding that he leave the place of the event.

7/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

In comparison with 2019, the quantity of attacks and threats via judicial and/or economic means increased by 11%.

The previous year’s trend of an increasing number of legal claims against journalists and media outlets continued. Of these, 77 incidents are connected with publications in which, in the plaintiffs’ opinion, insults and libel are contained. In yet another instance such charges were laid against the head of a media outlet on the part of the prosecutor’s office, but without recourse to a court. The initiation of court trials and charges of libel, insult, and reputational damage are the most widespread methods of pressure on journalists and media outlets.

Only in 20 cases were representatives of the authorities the initiators of the court trials.

- On 22 June minister of territorial administration and infrastructures of Armenia Suren Papikyan submitted a legal claim against the Hzham.am news website with demands for a public retraction of libellous data and payment of compensation. The occasion for the lawsuit became an article in which it is said that governors, with the ministry at the head, are getting flats in the capital as a gift for services rendered.

- On July 6th Yerevan’s court of general jurisdiction received a bill of indictment from the prosecutor’s office in a criminal case in relation to director of Skizb Media Kentron LLC Hasmik Martirosyan. He is charged with wilful non-fulfilment of a judicial act that has entered into force in a case involving the second president of Armenia, Robert Kocharyan. On 18 January 2019, a court of the first instance partially satisfied Kocharyan’s claim, having obligated Martirosyan to publicly retract the data that had been found to be libel, and to pay compensation in an amount of 400 000 drams. The court has agreed to hear the criminal case of non-execution of a court decision.

- On 10 July the chief of staff of the government of the RA, Eduard Aghajanyan, submitted a legal claim against the founder of the 168.am news website with demands on the retraction of information that the plaintiff considers libel, and the payment of compensation. The occasion for the lawsuit became the article “Party – at the ruling circles’ club «Fermata»”. In it, it is asserted that the night club, which belongs to Aghajanyan, had violated a police commandant’s office decree by having organised a party with the participation of several dozen people in a closed space, which is prohibited in the conditions of the state of emergency that was introduced in connection with COVID-19. The court has agreed to hear the lawsuit; a judicial inquiry is ongoing.

- On 25 November National Assembly deputy [MP] Hayk Sargsyan filed suit in Yerevan’s court of general jurisdiction against ArmDaily News Agency LLC with a demand for recovery of damages caused to honour, dignity, and business reputation by means of insult and libel. The lawsuit became about the expression “holder of the bottle” used at Sargsyan’s address on the ArmDaily.am news website. The court agreed to hear the lawsuit on 4 December; a judicial inquiry has begun.

In 68 instances, court trials were initiated by non-representatives of the authorities (current or former).

- On 24 February citizen Hayk Stepanyan submitted a legal claim against the Hayeli (Mirror) press club and its founder, the journalist Angela Tovmasyan, with demands to publicly retract libellous information and pay compensation. The occasion for the lawsuit became pronouncements addressed at Stepanyan at a press conference on January 22nd. The court agreed to hear the lawsuit; a judicial inquiry is ongoing.

- On 29 June Olimp Construction LLC filed a lawsuit in Yerevan’s court of general jurisdiction against the founder of the Hetq.am internet publication – Hetq LLC – with demands for retraction of libellous information and payment of compensation, despite the fact that the author of the material had taken the commentary from a representative of the real estate development company. The court agreed to hear the case; a judicial inquiry has begun.

- On 31 August former National Security Service employee Ara Harutyunyan submitted a legal claim against the founder of the 1in.am news website – Skizb Media Kentron LLC – with demands for a public retraction of libellous data and recovery of damages caused to honour and dignity. The occasion for the lawsuit became an article, in which states that Harutyunyan had been getting payoffs in envelopes for years in exchange for turning a blind eye to looting on the railroads and was organising illegal trade in smuggled goods.

Against the background of a rising tide of legal claims against media outlets and their employees, serious concern was evoked in the journalistic community by an initiative from vice-speaker of the National Assembly Alen Simonyan, who proposed increasing 5 fold the size of the monetary recovery for insult and libel prescribed by article 1087.1 of the Civil Code of the RA. The draft law’s author proposed instead of the maximum sums currently in effect – up to 1 million drams (around $2000) for insult and up to 2 million drams (around $4000) for libel – to prescribe 5 million ($10000) and 10 million drams ($20000), respectively. On 7 September 2020 this initiative was approved by the standing parliamentary commission on public law questions. 10 journalistic organisations noted in a joint declaration that the draft law poses a serious threat to freedom of speech and goes against the requirements of the Constitutional Court of the RA and international norms, and should therefore be withdrawn. As of the end of the year this draft law had not been placed on the agenda for plenary sessions of the National Assembly.

Also it is important to note the not-insignificant number of dismissals (10), including forced ones, and the resolution of labour disputes between editorial office employees and their employers through the courts.

- On 2 October Marine Kyureghyan, an employee of the daily newspaper Hayastani Hanrapetutyun (Republic of Armenia), was dismissed as the result of an internal conflict at the editorial office. On 23 November Kyureghyan referred to Yerevan’s court of general jurisdiction with a lawsuit against the legal successor of the publisher – Armenpress State News Agency CJSC. She demanded that orders on the application of a disciplinary penalty be ruled invalid, that she be reinstated at her former job, and that compensation be paid for forced unpaid time off. The journalists Naira Karapetyan, Tatevik Hambardzumyan, Gayane Antonyan, Lusine Mesrobyan, Khachik Sargsyan and Emil Sargsyan were also dismissed.

- On 21 December the Committee for the Protection of Freedom of Speech received a letter from employees of the Hayastani Hanrapetutyun newspaper in which it was reported that the editor-in-chief had dismissed his deputy Samvel Sargsyan and technical employee Mergevos Saakyan. The authors of the letter were complaining about arbitrariness on the part of the head of the publication and the unfavourable working conditions created by him.

GEORGIA

An independent expert opinion about Attacks on media workers in Georgia report

In Georgia, like in many other countries, media is essential for safeguarding transparency and thus preserving democracy in the country. While often referring to its role as ‘watchdog’, many media workers or journalists act as human rights defenders, especially those representing independent media, reporting on human rights violations, or expressing critical voices.

Unfortunately, last year, we have seen the alarming trend of intensified government pressure against critical voices in Georgia: attempts of interference with journalistic activities, cases of attacks against journalists, threats to the safety and ability to work of journalists during the protest actions. Of particular concern was the use of disproportionate and unjustified force against the peaceful activists, including journalists, at the rally of November 8, 2020. The journalists were implementing their professional activities, some of them live-streaming the demonstration in front of the central election commission. As a result of the dispersal of the rally, a number of journalists were injured, and several cameras were damaged. Unfortunately, this is not the only case of physical injuries of journalists during the protest action in the last years. During the dispersal of the June 20, 2019 demonstration, about 40 journalists were injured, some of them severely. However, the government did not adequately investigate or respond to these cases.

The developments over the Adjara Public Broadcaster – TV and Radio, dismissal of the journalists due to their critical and independent views, changing the organization’s editorial policy exemplified the pattern of fighting critical, opposition, or independent media. It also shows the challenges of the Public Broadcaster and the need to be a “real” representor of public interest.

Furthermore, in the cases where the problem was related to the professional or ethical issue of a particular media/journalist – the government or public officials’ response on that was not adequate and followed by unhealthy debate, harassment of a journalist, or attempts to interfere in media company activities. Together with extremely polarized media in the country, it is noteworthy that – self-censorship becomes a real challenge for quality journalism and media freedom. This refers not only to the government-friendly but also to the opposition-media.

It is vital to support and express solidarity to the journalists, especially while there is a rising number of attacks and killings of journalists in the world. The government of Georgia must publicly support the journalists, particularly independent journalists, and accept the critical views, condemn the attacks and intimidations against media representatives, and adequately and effectively investigate crimes committed against journalists.

Natia Tavberidze

Magistra Legum Europae/LL.M. EUR. with Merit

Coordinator of Human Rights House Tbilisi

Author of the report – Oleg Panfilov, Georgian journalist, commentator and writer.

1/ KEY FINDINGS

113 instances of attacks/threats in relation to professional and citizen media workers and editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Georgia in 2020 were identified and analysed in the course of the research. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Georgian, and English languages using the method of content analysis. Data that has previously not been made public and was obtained using the expert interview method was likewise used in the report. A list of the main sources is presented in Annex 11.

- The main method of pressure on journalists and media workers in 2020 became non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats, above all damage to/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials, print run.

- The majority of the events associated with restrictions on freedom of speech and judicial prosecution of journalists are associated with the 31 October parliamentary elections.

- 79 of the 113 attacks came from representatives of the authorities.

- The increase in the number of non-physical attacks and the reduction in the quantity of physical assaults on journalists can most likely be explained by the increased attention to the situation in the country on the part of international organisations, including human rights groups.

- 16 of the 26 physical attacks recorded in 2020 were carried out by representatives of the authorities; the greater part of the journalists suffered from tear gas poisoning and the use of water cannons (dousing with water containing chemical reagents) on the night of 8–9 November 2020 at the Central Electoral Commission building.

2/ THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MASS MEDIA IN GEORGIA

According to the data from the Reporters Without Borders NGOs annual rating, in 2020 Georgia held 60th place among 180 countries of the world in terms of the level of freedom of the press.

According to the research by DFRLab, almost 3 million people out of a total population of 3.7 million in Georgia have access to the internet, which represents a 79% rate of penetration for the internet. 96% of Georgian internet users use social media, especially Facebook. It is on Facebook that various online attacks against civilian and professional journalists are actively perpetrated, and disinformation and propaganda are systematically disseminated.

Television channels are the main source of news for the country’s population, the activity of which is regulated by the National Commission for Communications of Georgia and the Law On Electronic Communications, adopted in 2005. As of the beginning of 2021, there are 128 television channels and radio stations registered in Georgia; the majority of these are included in cable channel packages and offer viewers entertainment programmes and films.

Of all the mass media outlets, the only ones which receive state funding are Public Broadcasting (two television channels and one radio station) and the parliamentary bulletin, which publishes laws. A supervisory council consisting of representatives of the authorities and opposition parties oversees Public Broadcasting’s editorial policy.

There are about twenty private news television channels operating in the country, amongst which the leaders are Rustavi 2 and Imedi. Their ratings are roughly the same – these two channels together account for more than 80 percent of the country’s on-air space. According to surveys as of the beginning of 2020, many people preferred to watch these two channels.

The main television channels have a clear-cut political position, and their news policy is in line with this.

On the side of the Georgian Dream party of power is the Teleimedi holding company, which includes the Imedi and Maestro channels and the GDS network of channels, which belong to the founder of this party, Bidzina Ivanishvili. In July 2019, the formerly opposition Rustavi 2 acquired new owners and a new team of journalists and is now also loyal to the authorities.

In another group are channels that reflect the political priorities of the opposition: Mtavari Arkhi, Formula, Pirveli, and several regional television channels.

Entirely separate from these as a news source is the Obiyektivi television channel, which belongs to the founders of the pro-Russian party Alliance of Patriots of Georgia and has a stable viewing audience of 3.14% of the population.

On 17 July 2020, the Georgian parliament adopted amendments permitting the National Commission for Communications to appoint a “special manager” for a term of two years for operators of electronic communication networks, that is those broadcasting companies that are violating the commission’s instructions. This is a special administrator endowed with the right to fire and hire employees, enter into and tear up agreements, and revoke the decisions of directors, boards of governors, and shareholders.

Non-governmental organisations – members of the Coalition for Defence of the Interests of the Mass Information Media – have criticised the amendments numerous times: they indicated that the National Commission’s meddling in content is illegal and unacceptable. Members of the Coalition have roundly condemned the regulator’s actions in relation to the Mtavari Arkhi television channel, which was subjected to sanctions for an “indecent” story about coronavirus. Human rights advocates noted that establishing a practice that is incompatible with the legislation of Georgia represents a direct threat of censorship.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

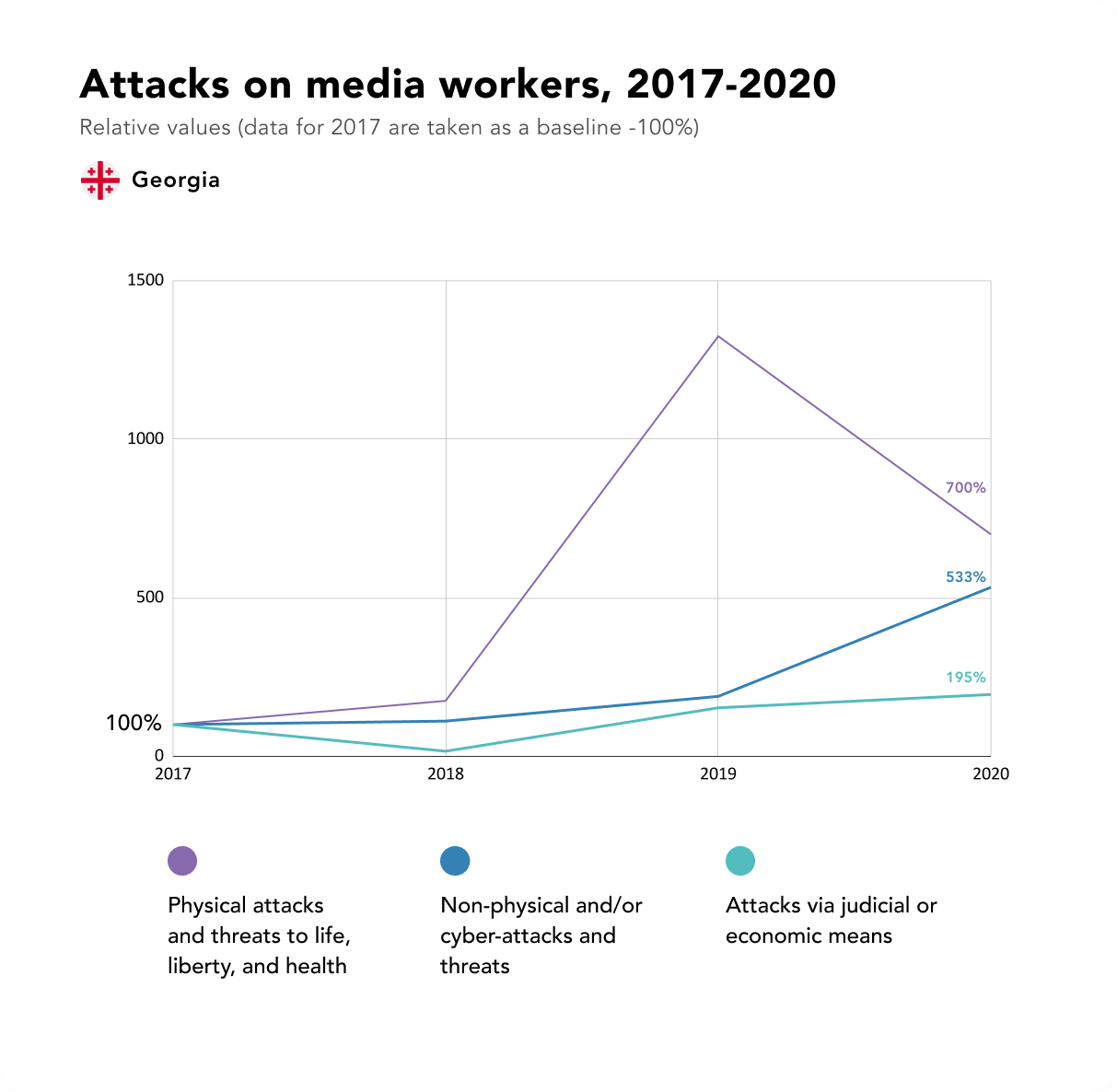

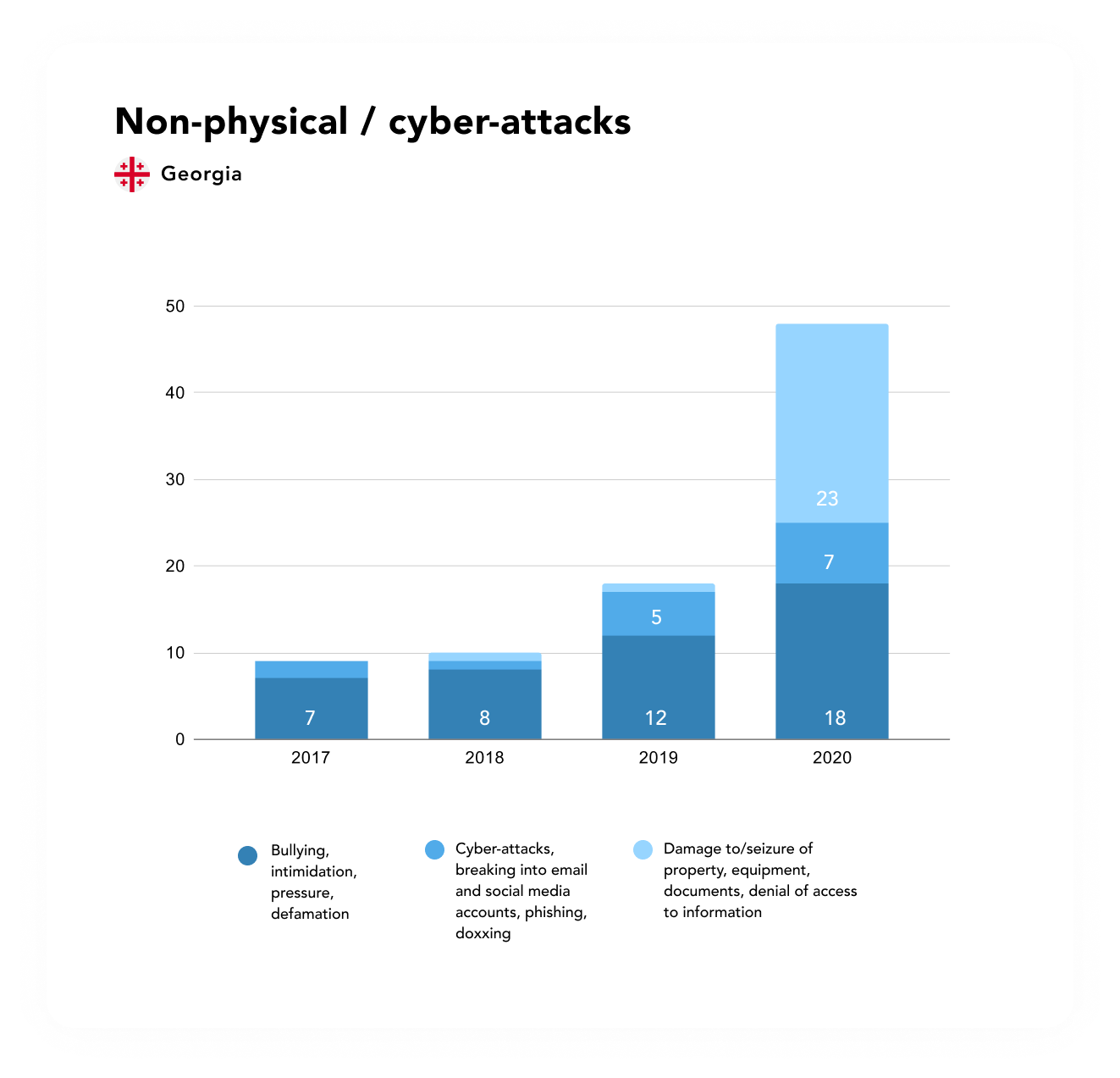

The quantity of attacks on journalists and media workers in Georgia has increased by nearly 3.5 times since 2017. The number of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats increased sharply in 2020.

In 2020, 79 of the 113 recorded attacks came from representatives of the authorities. They are also responsible for 16 of the 28 physical attacks.

As in 2019, the government’s main targets were opposition-oriented television channels – Mtavari Arkhi, Formula, and Pirveli, as well as employees of the Public Broadcaster of the Adjaran Autonomy who had spoken out against the channel’s pro-government policy. Tensions intensified as the elections approached: according to the data of NDI and IRI surveys, the coalition of opposition parties was running ahead of Georgian Dream. The government chose a tactic of pressure on the opposition channels with the use of the administrative resource, financial, judicial, and law-enforcement mechanisms.

4/ PRESSURE ON JOURNALISTS UNDER THE PRETEXT OF RESTRICTIONS CONNECTED WITH THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

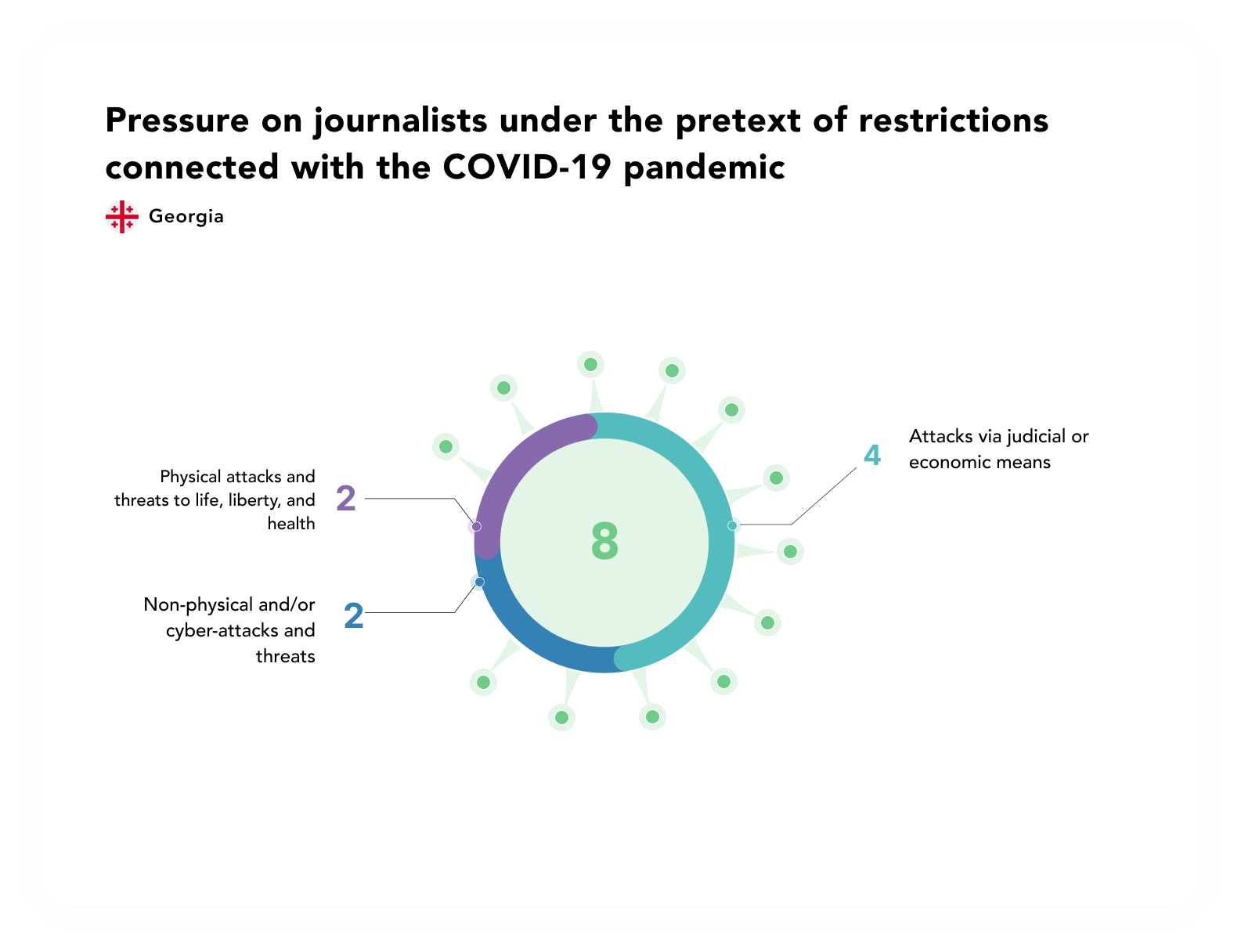

Eight incidents of persecution of journalists in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic were recorded in 2020: seven in Tbilisi and one in Svaneti, in the municipality of Mestia.

Of the eight incidents, two were physical attacks:

- On 14 April in Tbilisi, theologian and political columnist Gocha Barnovi was subjected to an assault during an interview with the Rustavi 2 television channel. An unknown person came up to him with grievances regarding Barnovi’s critical remarks addressed at Patriarch Ilia II (the Georgian Orthodox Church had refused to introduce quarantine restrictions during Easter divine services). This person hit the commentator.

- On 17 August, during a protest in Mestia against the prohibition on entering and leaving the municipality, mayor Kakha (Kapiton) Zhorzholiani tried to take a mobile telephone by force from the blogger Giorgi Chartoliani while the latter was filming Zhorzholiani’s talk with residents on the camera.

Two attacks are associated with non-physical threats:

- On 28 March, journalists from the Pirveli television channel became the object of verbal abuse and criticism on society’s part in connection with questions that had been posed by Vakho (Vakhtang) Sanaia during an interview with Centre for Disease Control head Amiran Gamkrelidze and his deputy Paata Imnadze on Pirveli’s daytime news programme.

- On 10 September, the government of Georgia prohibited correspondents from being present at a session of parliament on the grounds that “there may be persons infected with the coronavirus among the journalists”.

Four attacks were carried out via judicial and/or economic means.

- Chair of the opposition Republican Party and popular blogger Khatuna Samnidze was summoned for interrogation to the State Security Service (SGB) of Georgia. Serving as grounds were her comments to a post on another person’s Facebook page on the topic of coronavirus mortality statistics.

- On 26 June, independent journalist Nino Chelidze declared that she had been summoned to the SGB because of her Facebook status. “The questions concerned whether the Facebook account was mine. Likewise they asked me about whether it was I who had written this post. They asked if I happened to know anybody to whom, for example, money had been offered. Needless to say, I don’t have such information”, said Chelidze after the interrogation.

- On 2 July, the Tbilisi City Court issued a ruling in favour of the SGB, which had accused the Mtavari Arkhitelevision channel of sabotage and attempts to “disinform the populace by way of spreading false news about the novel coronavirus epidemic”, for the programmes Subbotnyaya sessiya on 20 June and Priobreteno COVID-19 on 25 June 2020. The court forced the channel to give the full and unedited material to the SGB for investigation. Director of the Mtavari Arkhi television company Nika Gvaramia accused the State Security Service of defaming the opposition television channel.

5/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

28 incidents of physical attacks on journalists were recorded in 2020. All of these incidents except for one attempted murder fall under the category of attacks of a non-fatal nature.

- On 15 June, director-general of the Mtavari Arkhi television channel Nika Gvaramia announced that an RF citizen, the Ingushetian native Vasambek Bokov, detained on 12 June as the result of a special operation in Tbilisi, had been preparing an attempt on the life of journalist Georgiy Gabuniya on assignment for head of Chechnya Ramzan Kadyrov.

All the instances of physical violence against journalists can be divided into three groups.

- Assaults perpetrated by people not associated with the authorities directly, for example the security guards of private enterprises or ideological supporters of the authorities.

Thus, during the time of the siege of the Rustavi 2 television channel, representatives of the pro-authorities and pro-Russian organisation Georgian March perpetrated an assault on the director-general of the Mtavari Arkhi television channel Nika Gvaramia and other journalists.

In two instances – in Martvili and Davidgaredji– the initiators of the assault were members of the clergy.

- Targeted actions by the police or representatives of the authorities against journalists carrying out professional duties.

On 8 November, the police used water cannons and tear gas to disperse people protesting against the falsification of elections at the Central Electoral Commission building. A group of journalists were amongst those targeted: Papuna Khachidze – a camera operator with the Pirveli television channel, Nika Matiashvili, Giorgi Japaridze, and SosoTsiklauri – camera operators with the Formula television channel, correspondent Ani Baratasvhili with the Formula channel, and a Rustavi 2 camera operator. All of them had their cameras damaged.

Journalists in Georgia do not wear special vests or other markers identifying themselves as a member of the press; however, it is entirely possible that the policemen had applied targeted force against the journalists in order to intimidate them.

The rest of the instances of assaults were the result of physical effect, when journalists were being pushed away or blows were being inflicted with the hands.

- Assaults on journalists not connected with their professional activity.

On 6 March, an assault was perpetrated on Beslan Kmuzov, a correspondent with the Caucasian Knot website, after his quarrel with neighbours. Kmuzov was detained by the police as the initiator of the quarrel; he was let out on bail by a court decision on 8 March, and released on 10 March.

6/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER-ATTACKS AND THREATS

The most widespread type of attacks in 2020 became non-physical and/or cyber-attacks and threats. 48 instances were recorded, which is nearly three times more than in 2019.

The overwhelming majority of the attacks took place during the pre-election campaign, in the period from August through October 2020.

- 12 instances were connected with equipment being damaged whilst journalists were carrying out their professional duties;

- 11 instances were connected with illegal impediments to journalistic activity and denial of access to information;

- 10 – with defamation and spreading libel about a media worker/media outlet;

- 6 – with bullying and intimidation of journalists.

The geographic breakdown of the offences in this category looked as follows. 25 incidents took place in Tbilisi; the rest in practically all the regions of the country, including occupied Abkhazia: 9 in Batumi and Khelvachauri of the Adjaran Autonomy; 3 in Telavi, administrative centre Kakheti; 3 in Abkhazia; 2 in Akhaltsikha; 2 in Marneuli; and one each in Poti, Vani, and Duisi.

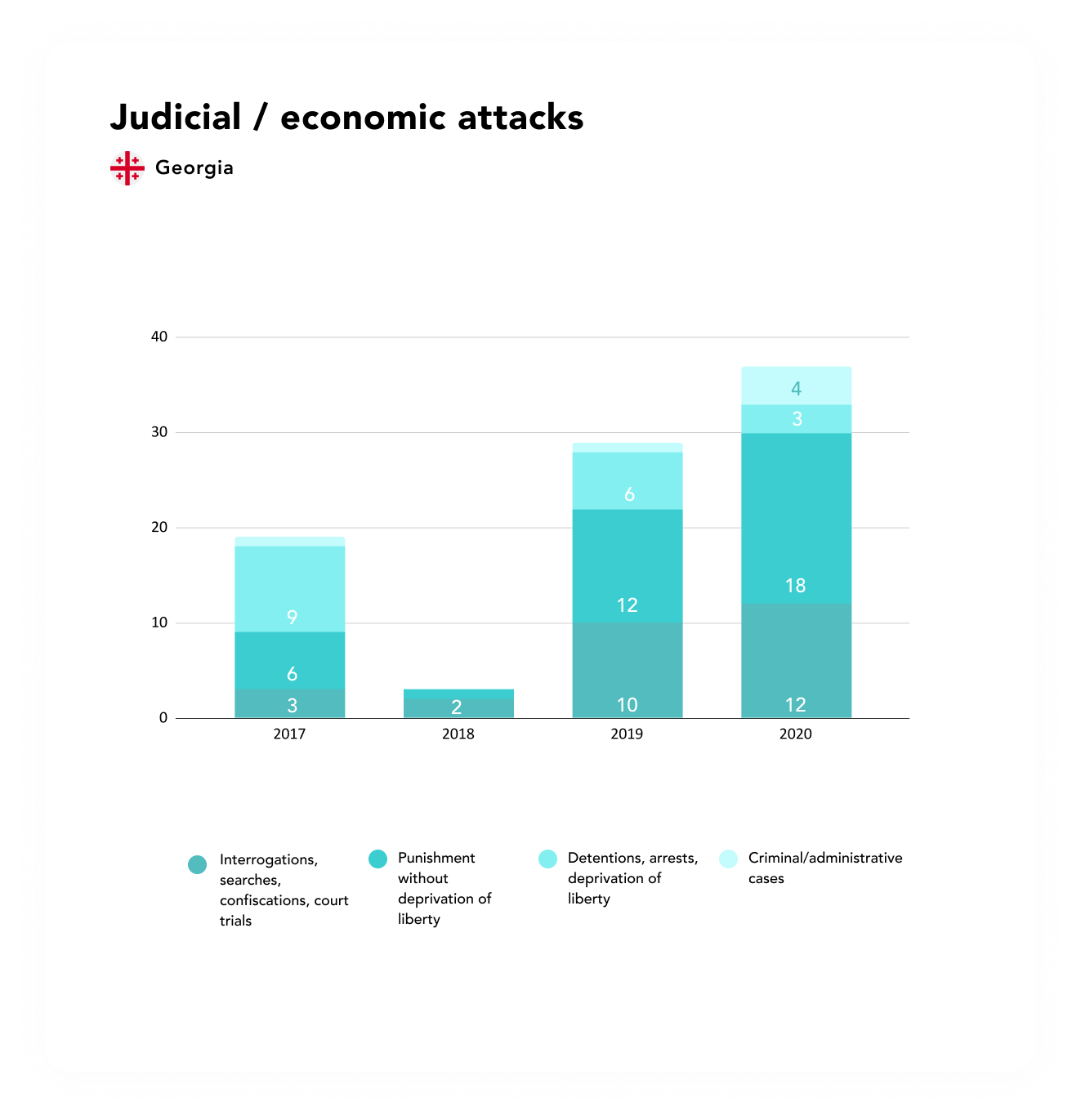

7/ ATTACKS VIA JUDICIAL AND/OR ECONOMIC MEANS

In general, Georgia’s legislation was raised to European standards in the period of reforms in 2004-2012; however, in the past few years the judicial system has been put into a position of dependence on the political will of the party of power.

Of the 37 instances of attacks against journalists and editorial offices of mass media outlets via judicial and/or economic means, 21 took place in Tbilisi.

In 2020, as in 2019, dismissal/involuntary dismissal/forced quitting of the profession was the most widespread means of pressure on journalists. All 12 instances of attacks of the given category were associated with the Public Broadcaster of the Adjaran Autonomy, when journalists became outraged over censorship and the news policy of the television channel’s management, which had taken a pro-government position.

- Dismissed employees Bacho Gurabanidze, director of the Dilistalgis (Morning Wave) programme; Giorgi Murvanidze, creative manager; and Guram Kadidze, graphics editor, declared that the channel’s director-general, Giorgi Kokhreidze, was harassing them for belonging to alternative trade unions and for participating in a protest rally on 26 June.

The second widespread means of pressure is interrogation/questioning: seven incidents of the given category were recorded in 2020.

- Five of the seven interrogations are associated with a criminal case of “misappropriation of funds” at the Rustavi 2 channel that was initiated back in 2019, in which the suspicion was placed on Niko (Nikoloz) Gvaramiya, who is currently director-general of the Mtavari Arkhi channel, the leading opposition broadcaster. Inasmuch as the channel is privately owned, the crime of “misappropriation” is not applicable to it. The channel’s lawyers deem that the criminal prosecution is a part of state policy in relation to the opposition.

4 instances were noted in the category of court trials – two of them are connected with the Niko Gvaramiya case, and one with the domestic conflict involving the journalist Beslan Kmuzov.

On 20 March, the revenue service of the Ministry of Finance of Georgia imposed a collection order on the bank accounts of the Mtavari Arkhi and Pirveli television companies.

Since November 18, 2109 Giorgi Rurua, co-owner of the main opposition TV channel Mtavari Arkhi, has been in prison on charges of illegal acquisition, possession and carrying of firearms. The European Parliament has officially recognized Giorgi Rurua as a political prisoner. Nika Gvaramia, the director of this TV channel is constantly dragged to court. This situation cannot but have a negative impact on the functioning of the TV channel itself.

A bit of history: Rustavi 2 and Imedi

Rustavi 2

The history of the television channel began in 1994 with a studio in a small flat in the metallurgical city of Rustavi, after two separatist wars in Abkhazia and Tskhinvali.

In 1998 Rustavi 2 was already the country’s leading television company, with its own agency and newspaper.

With the growth in the channel’s popularity came problems with the authorities – abductions, beatings of journalists, searches, denial of airtime, an attempt by supporters of Eduard Shevardnadze to buy out the channel. In 2001, the popular presenter Giorgi Sanaya was murdered in his own flat.

In November 2003 Rustavi 2 made it into the top leagues of world television brands – CNN and BBC broadcast live footage of the “Rose Revolution” from Tbilisi.

In June 2004, already under Mikheil Saakashvili’s new reformist power, the channel unexpectedly announced its bankruptcy, and 90% of the shares in Rustavi 2 were sold to an entrepreneur from Batumi, Kibar Khalvashi, owner of the Georgian marketing network of the Procter & Gamble company.

In 2006, Khalvashi sold his block of shares to the deputy [MP] David Bezhuashvili. After that, the television channel entered into a media holding, the co-owners of which were the Georgian Industrial Group and Geomedia Group.

In 2008, 30% of the shares in Rustavi 2 were acquired by the channel’s director-general Irakli Chikovani; Geomedia Group was left with 40%, and the Georgian Industrial Group with 30%.

In 2009, Rustavi 2 director-general Erosi Kitsmarishvili filed a lawsuit in which he demanded that Khalvashi return the 30% of the television company’s shares, while the stakes owned by Chikovani and Geomedia Group should be transferred to the Degson Limited company.

The founder of Rustavi 2, Erosi Kitsmarishvili, died unexpectedly in June 2014. The authorities announced it as a suicide, but neither the family nor friends believe this hypothesis, deeming that he had been murdered, while the motive may have been information about who is the real owner of Rustavi 2.

After the falsification of the results of the 2016 parliamentary elections, Rustavi 2 was constantly criticising the authorities, speaking about the revival of corruption, nepotism, the rise in crime, and the struggle with the political opposition.

On 7 July 2019, Rustavi 2 channel television presenter Georgiy Gabuniya cursed out Vladimir Putin live on the air in his original programme Postscriptum. By 18 July, the owner of Rustavi 2 once again became the businessman Kibar Khalvashi, who fired all the leading journalists.

An absurd charge of misappropriating the funds of Rustavi 2 was brought against former director-general of Rustavi 2 Niko Gvaramiya.

In September 2019, Gvaramiya registered a new channel, Mtavari Arkhi (Main Channel), which is gaining in popularity whilst Rustavi 2’s ratings are falling.

Imedi

The Imedi (Hope) channel was created by a Russian entrepreneur of Georgian origin, Bardi (Arkady) Patarkatsishvili. The idea for the appearance of the channel emerged in a symbolic year for Russian journalism, 2001 – it is precisely at this time that the Kremlin destroyed the NTV television channel and Yevgeny Kiselyov’s team.

Patarkatsishvili was at that time director-general of the Russian ZAO MNVK (TV-6), simultaneously holding the post of deputy director-general of the Public Russian Television (ORT) television channel for commerce; he was the first deputy chairman of the OAO ORT board of directors.

Patarkatsishvili invited those who had at one time created NTV – Vsevolod Vilchek’s group – to create Imedi, but announced right from the start that the new channel would be opposition-oriented. Huge sums were spent on Imedi with one purpose – to overtake Rustavi 2. The main topic of the news agenda was advancing Patarkatsishvili for president of Georgia.

On 8 November 2007, a group of spetznaz state security forces burst into the Imedi studio, stopping a live broadcast, when the presenter of the news programme was calling the population to insurrection.

Patarkatsishvili lost the elections, and a month later, on 12 February 2008, he died suddenly as the result of a cardiac seizure in his home in the county of Surrey in the south of England. Before this, the Georgian and Russian press had published his secretly recorded conversation with colonel of the Georgian special services Irakli Kodua, in which Patarkatsishvili boasted that it was he who had brought Vladimir Putin into politics: “He (Putin) was in Saint Petersburg, was working as Sobchak’s deputy, was providing a ‘roof’ [protection] for my St. Pete businesses”.

After Patarkatsishvili’s death, the new owner of Imedi became the American Joseph Kay (Iosif Kakalashvili), a first cousin of the deceased. Badri Patarkatsishvili’s family declared that Joseph Kay was a “usurper”.In 2009, the channel became the property of the Arab-Georgian company RAK Georgia Holding. After Georgian Dream’s victory, Patarkatsishvili’s family managed to get back the channel, which then became the main propagandist of the new power – the old nomenklatura from the Georgian Dream party under the leadership of yet another Russian oligarch, Bidzina Ivanishvili.

KYRGYZSTAN

An independent expert opinion about Attacks on media workers in Kyrgyzstan report

Kyrgyzstan, which only recently was known for its high level of freedoms in the sphere of journalism in comparison with the neighbouring countries of Central Asia, has tumbled in the ratings to the dangerous level of a “not free” country.

For a long time the turbulence inherent in the political space of Kyrgyzstan did not affect the mass media; however, it has now gripped the entire media sector, including social media.

Journalists and bloggers covering the most sensitive topics of the previous year in Kyrgyzstan – the revolution in October, the government’s incommensurate reaction to the COVID-19 epidemic and its inability to prevent the socio-economic fallout from it, the large-scale corruption in the state customs inspectorate, the mass violations during the time of the parliamentary elections – were subjected to a comprehensive attack on the part of the authorities and political influence groups involved in corruption.

Aggression in relation to media workers and bloggers was being expressed in threats, hacker attacks, raider capture of an entire media enterprise, and physical violence, including in retaliation for publishing the results of an independent investigation of facts of corruption, as well as in exceeding official powers and vigilantism.

The extraordinary situation that has emerged in Kyrgyzstan, including as the result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the revolution of 5 October 2020, has been marked by unprecedented pressure on independent media outlets and a sharp rise in the level of impunity for state bodies of power.

Thus, the recognised prisoner of conscience Azimzhan Askarov [Alimjon Asqarov] perished under extremely murky circumstances in prison, despite a multitude of requests for him to be rendered urgent medical assistance.

Editor-in-chief of Factcheck.kg Bolot Temirov, famous for his anti-corruption investigations, was beat up right next to his office.

An entire online campaign of threats and insults with features of xenophobia and misogyny was rolled out against independent journalist Alena Khomenko.

Security personnel were torturing foreign journalist Bobomurod Abdullayev, temporarily found in Kyrgyzstan, and extradited him at the request of Uzbekistan, despite his request to be granted asylum.

Judicial authorities likewise played a role in restricting freedom of speech. In 2020 the verdicts issued by courts in lawsuits against journalists did not appear just, as they were protecting the positions of individual state officials the source of whose assets was raising questions among the public.

The authorities were in essence encouraging aggression in relation to the media, leaving journalists’ and bloggers’ police reports about threats and the impeding of their work without attention. But things were not limited to this. A series of legislative acts was adopted that significantly restricted freedom of speech and access to information. Besides that, violence against professional and citizen journalists on the part of the law-enforcement agencies demanding the retraction of publications in online publications and on social networks acquired a systematic character.

Ernest Zhanaev

Independent human rights researcher,

Master’s programme in Middle East, Caucasus and Central Asian Security Studies, University of St Andrews

Author of the report – School of Peacemaking and Media Technology in Central Asia

1/ KEY FINDINGS

86 instances of attacks/threats in relation to professional and citizen media workers and editorial offices of traditional and online publications in Kyrgyzstan in 2020 were identified and analysed in the course of the research. The data were obtained from open sources in the Russian, Kyrgyz, and English languages using the method of content analysis. A list of the main sources is presented in the Annex 12.

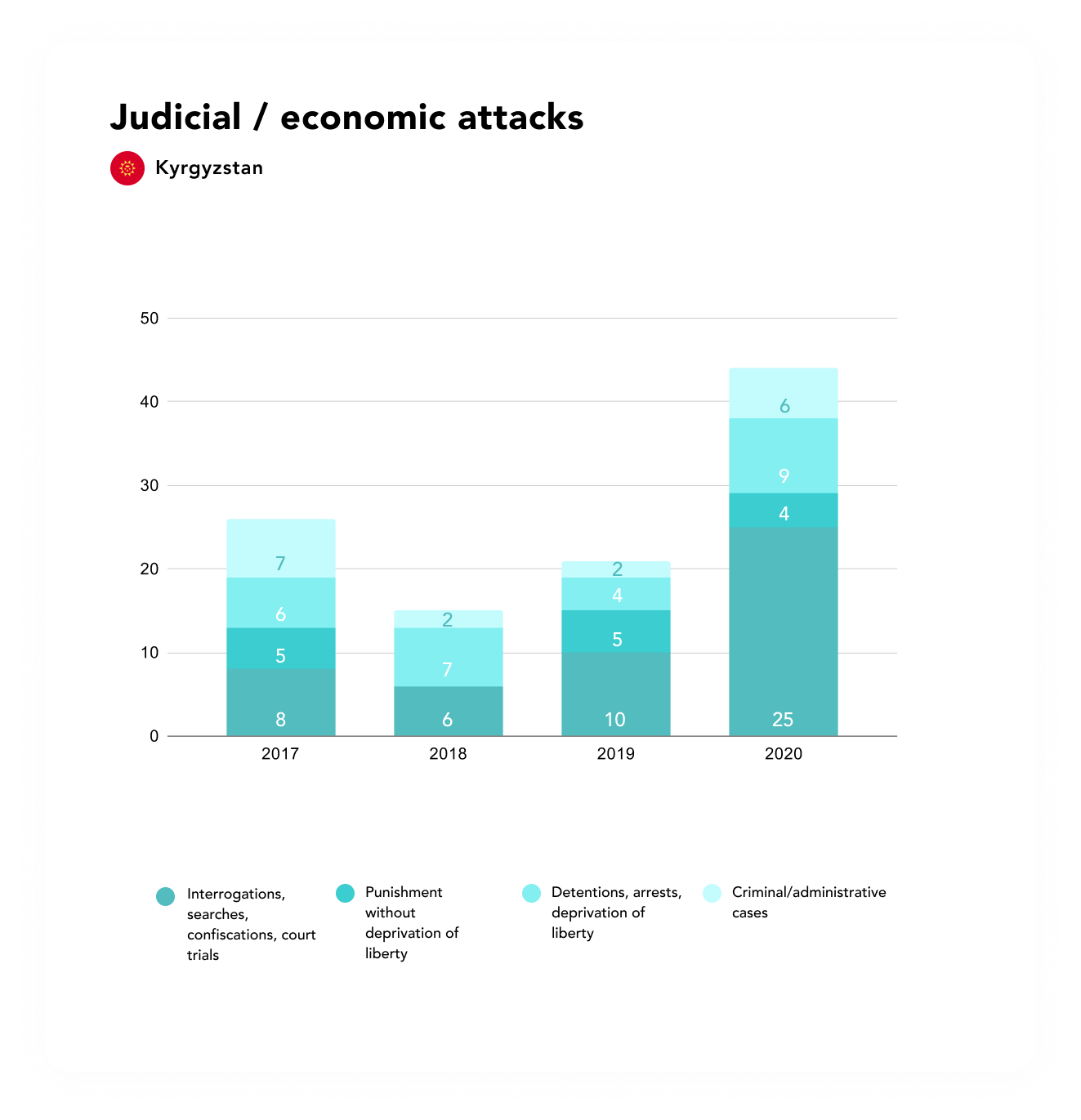

- The main method of pressure on journalists, bloggers, and media workers in Kyrgyzstan, as in previous years, were attacks via judicial and/or economic means.

- A record quantity of summons of journalists for interrogations was recorded in 2020 – 15 (there had been 6 such incidents in 2019, 4 in 2018, and one in 2017).

- The greatest number of attacks occurred in the period after the civil disobedience on 6 October.

- A general narrowing of the space for freedom of speech was observed in 2020 in Kyrgyzstan against a background of legislative initiatives encouraging censorship, sanctions for “manipulating information”, and crackdowns on investigative journalists and bloggers.

- The journalist and human rights advocate Azimzhan Askarov [“Azimjon Asqarov” in Uzbek] died on 25 July 2020. He had been imprisoned for more than 10 years. The State Service for the Execution of Punishments had been asserting that the journalist, who had been sentenced to life imprisonment, did not have problems with health, and was not providing him medical assistance. In 2016, the United Nations Human Rights Committee declared Askarov a victim of torture and all court decisions in his criminal case to be unjust and recommended his release. He was accused of inciting inter-ethnic discord and killing a policeman during ethnic violence in southern Kyrgyzstan in 2010.

2/THE POLITICAL SITUATION AND THE MEDIA IN KYRGYZSTAN

Kyrgyzstan took 82nd place in the Reporters Without Borders non-profit’s annual rating for 2020. The situation with freedom of the press in the country improved insignificantly over the year: Kyrgyzstan held the 83rd spot in the rating in 2019, and 98th in 2018.

According to the rating of the international human rights organisation Freedom House, for the first time in the last 11 years, Kyrgyzstan moved from the list of “partly free countries” to “not free” ones. It is clarified in the report that “Kyrgyzstan’s status declined because the aftermath of the deeply flawed parliamentary elections featured significant political violence and intimidation that culminated in the irregular seizure of power by a nationalist leader and convicted felon who had been freed from prison by supporters.”

55 television companies (3 of them state-owned), 26 radio stations, 68 newspapers, and 75 news agencies and online publications operate in Kyrgyzstan as of 1 September 2020. Such data was cited in the mass media on the eve of the the agitational campaign before the parliamentary elections. There is no other data as of the moment of publication of the report.

By law, 50% of media content must be published in the state (Kyrgyz) language; therefore, practically all media outlets in Kyrgyzstan are multilingual. The bulk of them come out in two or three languages – Kyrgyz, English, and Russian.

Pluralism is present in a series of media outlets, especially in the Kyrgyz language; a narrowing of the space for freedom of speech is being observed in recent years, however, due to the strong informational influence of Russian propaganda channels, the greater part of which broadcast as part of free digital bundles on the territory of Kyrgyzstan.

2020 in Kyrgyzstan was marked by large political upheavals. A third revolution took place unexpectedly in the country: on 6 October, thousands of citizens who disagreed with the results of the parliamentary elections stormed a series of administrative buildings in Bishkek, including the House of Government.

The ensuing events – the declaration of the results of the elections as invalid, the resignation of the president, extraordinary presidential elections, and initiatives with respect to changing the Constitution – merely worsened the situation with rights and liberties, which reflected on the media and journalists. Against the background of the raider captures of ownership that accompany all revolutions in Kyrgyzstan, many media outlets’ editorial offices were subjected to assault and takeover.

Alarm was raised by the initiatives of the new authorities. For example, within the framework of an Edict on the Mass Information Media, it was recommended to “propagandise the values of traditional society”, which many interpreted as an introduction of censorship.

The situation was exacerbated by the adoption by parliament of a law On Manipulating Information, which establishes censorship. This law allows the authorities to demand the removal of information which in the opinion of bureaucrats is “unreliable” from internet sites without a court’s sanction. The concept of an “authorised body” that is going to issue decrees about the removal of “false” information is introduced; however, it is not clarified exactly who is going to be identifying such content, in what manner, and by what criteria. The adoption of the law evoked mass protests in Bishkek. Thousands attended the “ReAction” march in defence of freedom of speech on 29 June.

Uncovering corruption in the bodies of power continued after the high-profile journalistic investigations of 2019. This work encountered obstables; harassment of the media and attacks on freedom of expression intensified.

3/ GENERAL ANALYSIS OF ATTACKS

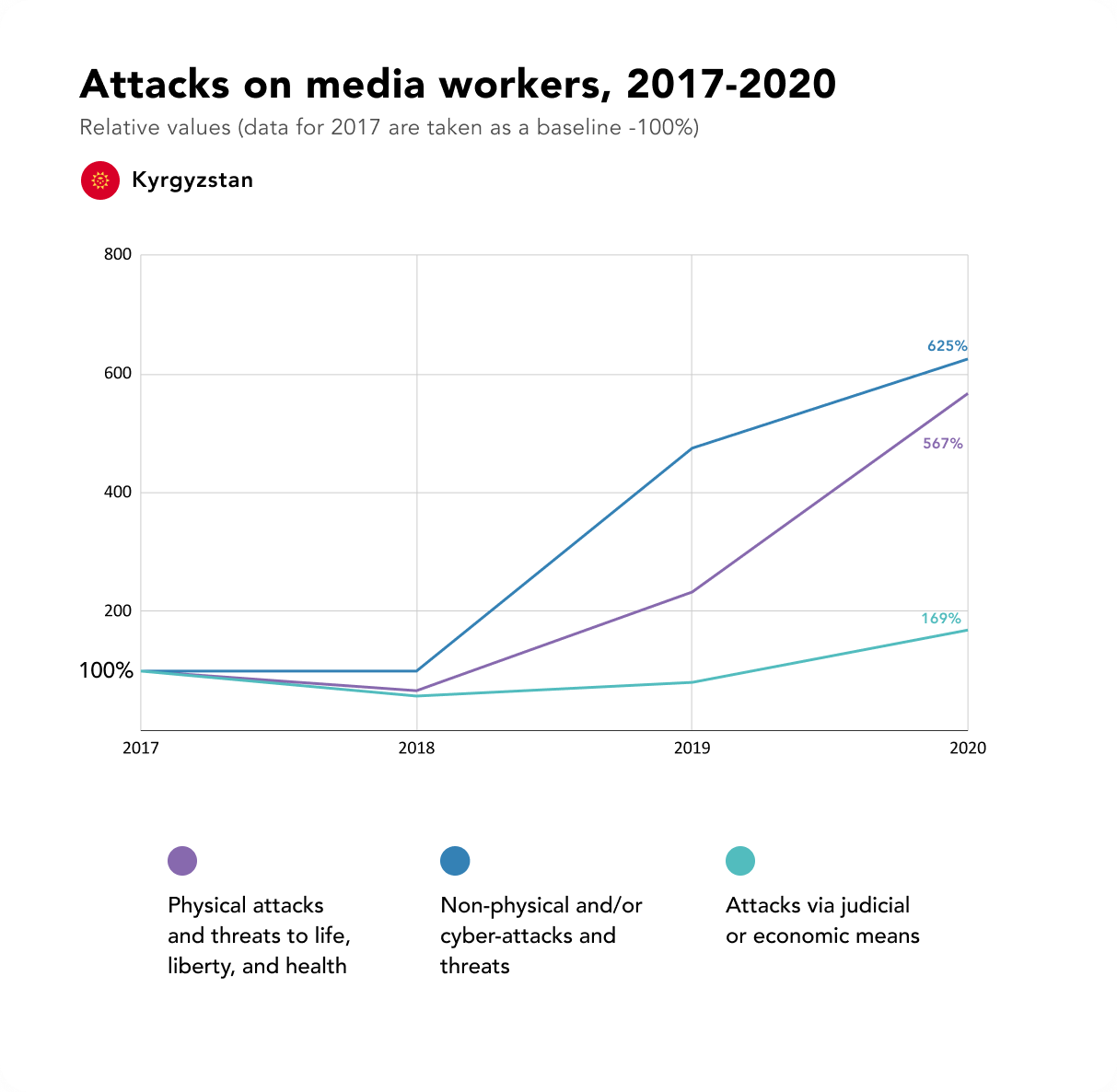

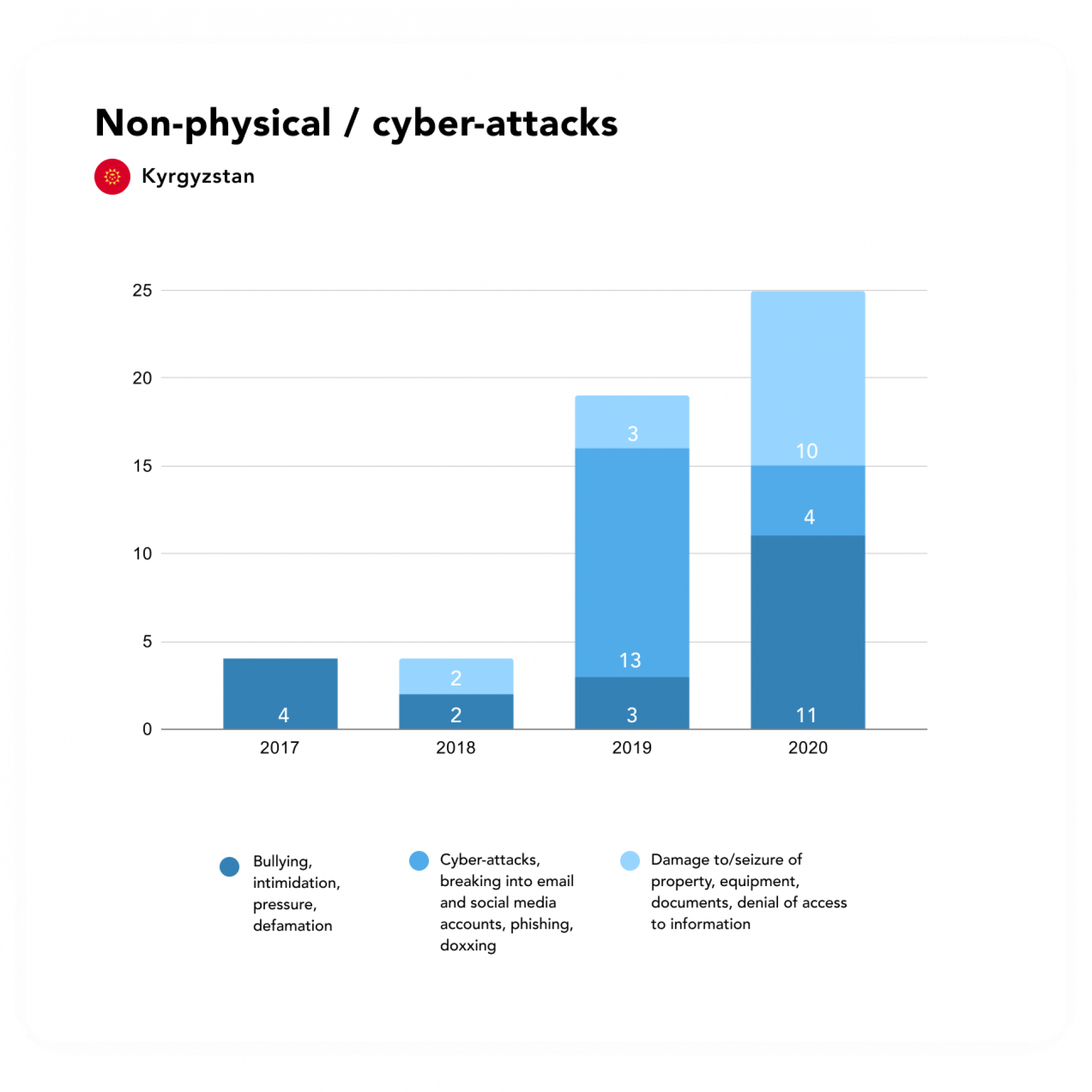

86 attacks/threats in relation to journalists, bloggers, media workers, and editorial offices of traditional and online publications were recorded throughout 2020, 83 percent more than in 2019. The number of physical attacks and attacks via judicial and/or economic means increased two-fold; the quantity of non-physical and/or cyber-attacks increased somewhat as well.

The upsurge in attacks was connected with the political upheavals and the pandemic:

- At least 10 journalists and media workers suffered physically whilst covering street protests and dispersals of demonstrators in the period from 5 through 10 October 2020. In three of these instances, the correspondents were attacked by the police and spetsnaz.

- The revolutionary events in the country reflected on the cyber-security of journalists as well: in private conversations they were reporting about constant trolling and online threats during coverage of sensitive socio-political topics. Many of the correspondents, fearing direct threats, were deleting their social media accounts and creating new ones, trying not to advertise this.

- In the first days after the revolution, a series of attempts were undertaken at raider captures of media outlets, which were accompanied by assaults.

- Emergency regimes were introduced in a series of Kyrgyzstan’s cities and regions in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic, which turned into disproportionate restrictive measures in relation to media outlets and journalists.

- New laws were adopted encouraging censorship, sanctions for “manipulating information”, and a continuation of crackdowns on investigative journalists and bloggers.

4/ PRESSURE ON JOURNALISTS UNDER THE PRETEXT OF RESTRICTIONS CONNECTED WITH THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The precise quantity of media outlets that were denied accreditation during coverage of the topic of COVID-19 in the quarantine period is unknown. According to expert estimates, it is around 25-30 media outlets.

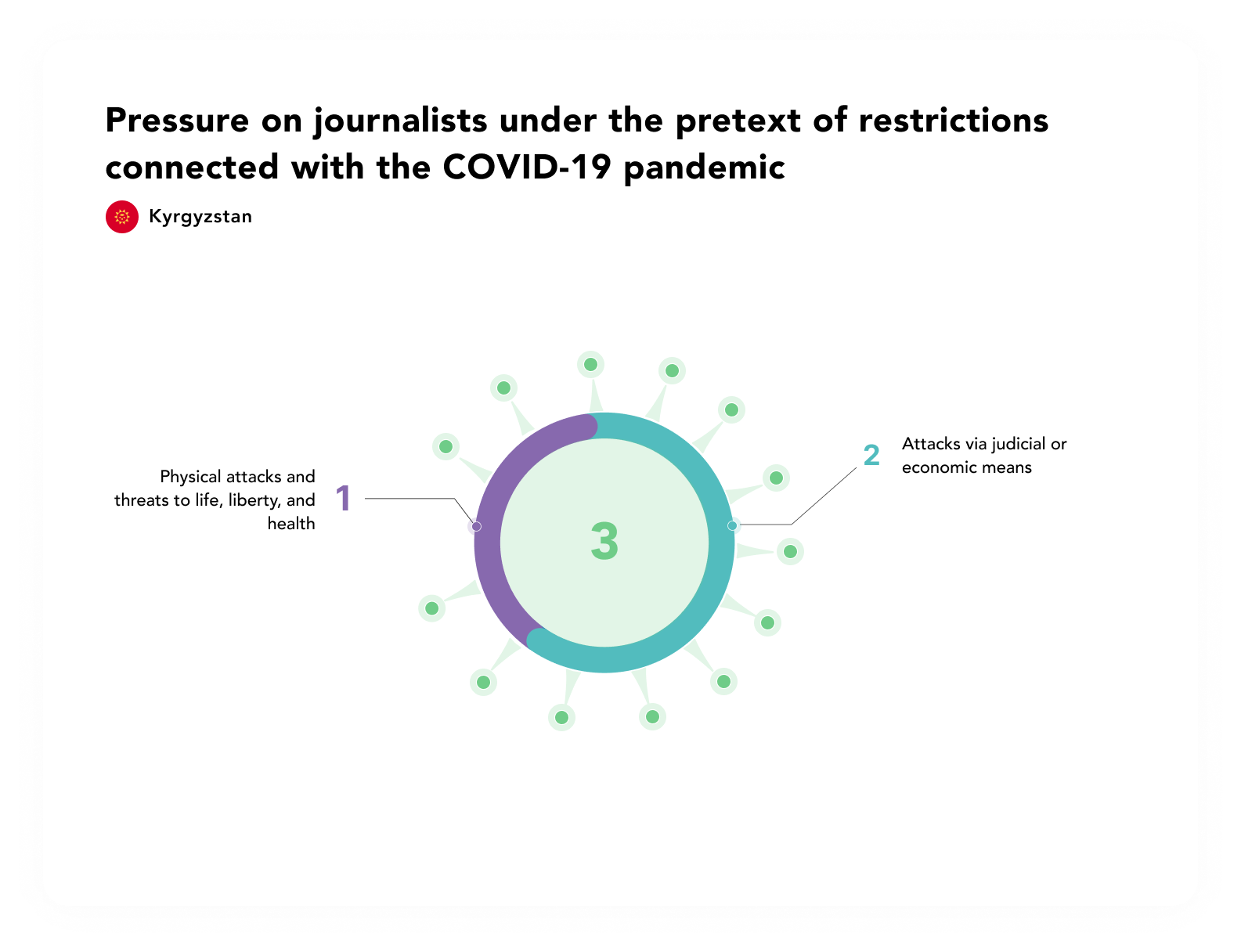

In March-April 2020, the authorities forced bloggers and journalists to apologise for criticism addressed at the government in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic. The Foundation has recorded three attacks connected with the adoption of quarantine measures in the period of the pandemic:

- On 30 March, the authorities denied Kyrgyzstan’s media outlets accreditation in the period of the state of emergency for coverage of the coronavirus pandemic. Bishkek’s police commandant Almazbek Orozaliyev explained this as concern for the health of the journalists.

- On 11 June, Kaktus.media correspondent Marat Uraliyev was conducting a video shoot in the vicinity of the Kaynar restaurant in Bishkek, where many high-level politicians and officials had gathered, including parliamentary deputies [MPs]. The journalist was intending to raise the question of violation of quarantine rules – the prohibition on mass events. However, during the time of the video shoot one of the security guards assaulted Uraliyev and began to choke him. The journalist managed to free himself and report the incident to the police.

- On 13 August, Marat Uraliyev was summoned for interrogation to the police of Kara-Suu District of Osh Region. They did not explain the reason; however, in the editorial office, they are confident that this is connected with his professional activity. In July, the journalist had been shooting video for a report about how there was a wedding being conducted in the Bayastan restaurant, situated in Kara-Suu District, in the period of the pandemic despite the prohibition. In his material the journalist showed that the guests at the event were deputies [MPs], employees of the GKNB [State Committee for National Security], and other high-level officials. Earlier, in June, a criminal case had been initiated in relation to the administration of the cafe under the criminal code article “Violation of sanitary-epidemiological rules”.

5/ PHYSICAL ATTACKS AND THREATS TO LIFE, LIBERTY, AND HEALTH

Physical attacks and/or threats to life, liberty, and health in relation to journalists and media workers were most often perpetrated in the moment they were carrying out professional duties.

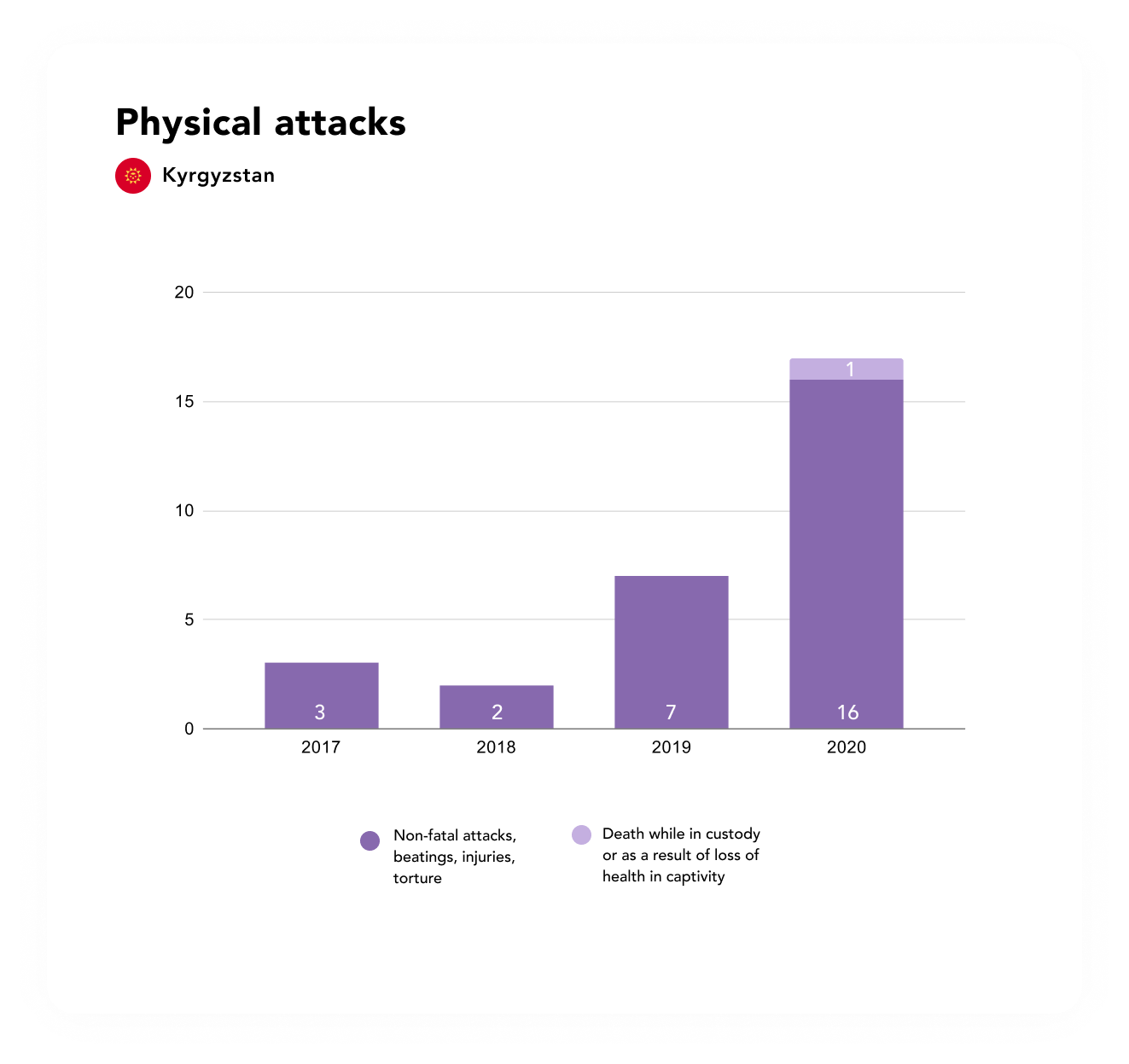

In comparison with the previous year, the quantity of physical attacks increased more than two-fold: from 7 incidents in 2019 to 17 in 2020. 15 episodes are attributable to the “non-fatal attack/beating/injury/torture” category. One incident of attempted murder was recorded during the period of the October protests:

- On 5 October, Nastoyashcheye vremia [Current Time] correspondent Aybol Kozhomuratov published a video recording on his Twitter account in which a spetsnaz soldier is firing at him during a video shoot of the disturbances on the street. In the journalist’s words, he was wearing a reflective vest, and the security man could see that he was filming the incident.

One journalist died while incarcerated:

- Journalist and human rights advocate Azimzhan Askarov, sentenced to life imprisonment, died on 25 July in penal colony No. 19 in the village of Jany-Jer of the Chuy Region. He had had problems with his health; they were however denying this at the State Service for the Execution of Punishments. Askarov was imprisoned in June 2010 on charges of inciting inter-ethnic discord and killing a policeman during ethnic violence in the south of Kyrgyzstan in 2010.

More than half (9 out of 17) of the documented attacks occurred in October 2020. In the majority of cases attacks of the given type were likewise accompanied by damage to/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials:

- On 4 October, an unknown woman attacked Radio Azattyk journalist Aygerim Asylbekova, who was broadcasting live on the air from a polling station during the time of parliamentary elections. The assailant damaged a camera and was demanding that the video shoot be stopped.

- On 5 October,Vesti.kg journalist Eldos Kazybekov was conducting a video shoot of a clash between rally participants and state security personnel in the centre of Bishkek. One of the law-enforcement agency employees threw a rock at him.

- On 6 October, correspondents and camera operators from the Reporter.kg, 24.kg, and Kloop.kg news agencies were subjected to an assault on the part of protesters in the centre of Bishkek. Several people were aggressively trying to take away recording equipment from the Kloop.kg camera operators. The correspondents from Reporter.kg had their smartphones taken away, which they had been using to conduct a video shoot.

- On 6 October, Radio Azattyk regional correspondent Dastan Ümötbay Uulu was subjected to an assault from an aggressively disposed crowd when he was covering a rally in the city of Osh.

- On 7 October, kaktus-media journalist Tanzilya Mingaliyeva was broadcasting live on the air from a rally by supporters of Sadyr Japarov, who won early presidential elections in January 2021. At this moment several drunk people surrounded the journalist, assaulted her, and took away a smartphone with force. Neighbourhood watch citizen volunteers who happened to be passing by helped Mingaliyeva fight off the assailants. They returned the telephone to the journalist.

- On 10 October, freelance photo reporter Igor Kovalenko was setting off for a photoshoot in the village of Koy-Tash, where the residence of former president Almazbek Atambayev is situated. When Kovalenko got close to a checkpoint, three military service personnel blocked his way and grabbed a camera from his hands, declaring that taking photos isprohibited. The journalist managed to hold on to his camera and to break through the checkpoint.

Other assaults on media workers connected with their professional activity were recorded over the reporting period as well:

- On 9 January, editor-in-chief of Factcheck.kg Bolot Temirov was beaten up near his office in Bishkek. Three unknown men of an athletic build assaulted him, knocked him down, were beating him for several minutes, and took away a telephone. Factcheck.kg is famous for its investigations of contentious topics.

- On 8 March, April TV channel journalist Kanat Kanimetov was beaten in Bishkek by five policemen, sustaining injuries to his head and kidneys. He was broadcasting live on the air from a march by feminists against violence and for women’s rights. A fight broke out at the event when members of a right-wing extremist grouping attacked the march participants.

- On 8 March, Kloop.kg journalist Ayzirek Imanaliyeva was assaulted by a radical right grouping during the feminists’ march. One of the nationalists grabbed her smartphone from her and smashed it.

6/ NON-PHYSICAL AND/OR CYBER ATTACKS AND THREATS

The most widespread methods of pressure in the given category are damage to/seizure of property, vehicles, equipment, documents, journalistic materials, print run (8) and bullying, intimidation, pressure, threats of violence and death, including cyber- (8).

The most common category were threats to journalists and bloggers from unknown perpetrators (19 of the 25 incidents) – on the internet, by telephone, or on the street. All of the threats were connected with journalistic activity, while the main goal of the assailants was to silence the media workers.

During the October events, trolling of journalists was so intense that many of them were simply deleting their social media accounts and setting up new ones. As one of the journalists at a seminar on fighting against gender stereotypes and online harassment organised by the School of Peacemaking and Media Technology in Central Asia clarified, in some cases “it was easier to delete your social media account and start a new online life, than it was to try and sort things out with them and to complain, because you’re not going to get to the truth anyway”.

- On 3 March, unknown persons broke into the editorial office of the online publication PolitKlinika and took away a hard drive and journalists’ writing pads. Prior to this, the publication’s reporters had been conducting investigations dedicated to the property of the now already former mayor of Bishkek, Albek Ibraimov, charged together with ex-president Atambayev with crimes in office.

- In the period from 10 to 12 May, trolls were calling for protests in the name of the April TV. The calls to attend rallies were disseminated on social media supposedly on behalf of journalists from the opposition television channel, which belongs to former president Almazbek Atambayev. Management of the television company called the provocative calls a “ludicrous and outrageous fake”, while media experts assessed this as a deliberate attack with the aim of discrediting April‘s TV journalists.

- On 7 June, unknown persons threw a bottle with an incendiary mixture into the office of the independent television channel 3 in the city of Talas. All equipment necessary for broadcasting was incinerated during the time of the fire. The head of the media outlet, Jannat Toktosunova, declared that the arson had been “deliberate and planned with the aim of intimidating journalists”.